Evaluating Salivary Cortisol and Alpha-Amylase as Candidate Biomarkers in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

- (i)

- Population: individuals of any age or sex, including both adults and children;

- (ii)

- Exposure: patients diagnosed with AN based on clinical evaluation and/or according to the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases;

- (iii)

- Comparison: studies that included a healthy control group with normal-weight individuals;

- (iv)

- Outcomes: studies that reported the means (or medians) and standard deviations (or standard errors or interquartile ranges) for salivary cortisol and/or alpha-amylase levels;

- (v)

- Study design: observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort, or case–control studies) or interventional trials.

- (i)

- animal subjects;

- (ii)

- review articles, meta-analysis, and conference abstracts;

- (iii)

- unavailability of the full text article;

- (iv)

- non-English publications.

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Flow

3.2. Study Characteristics

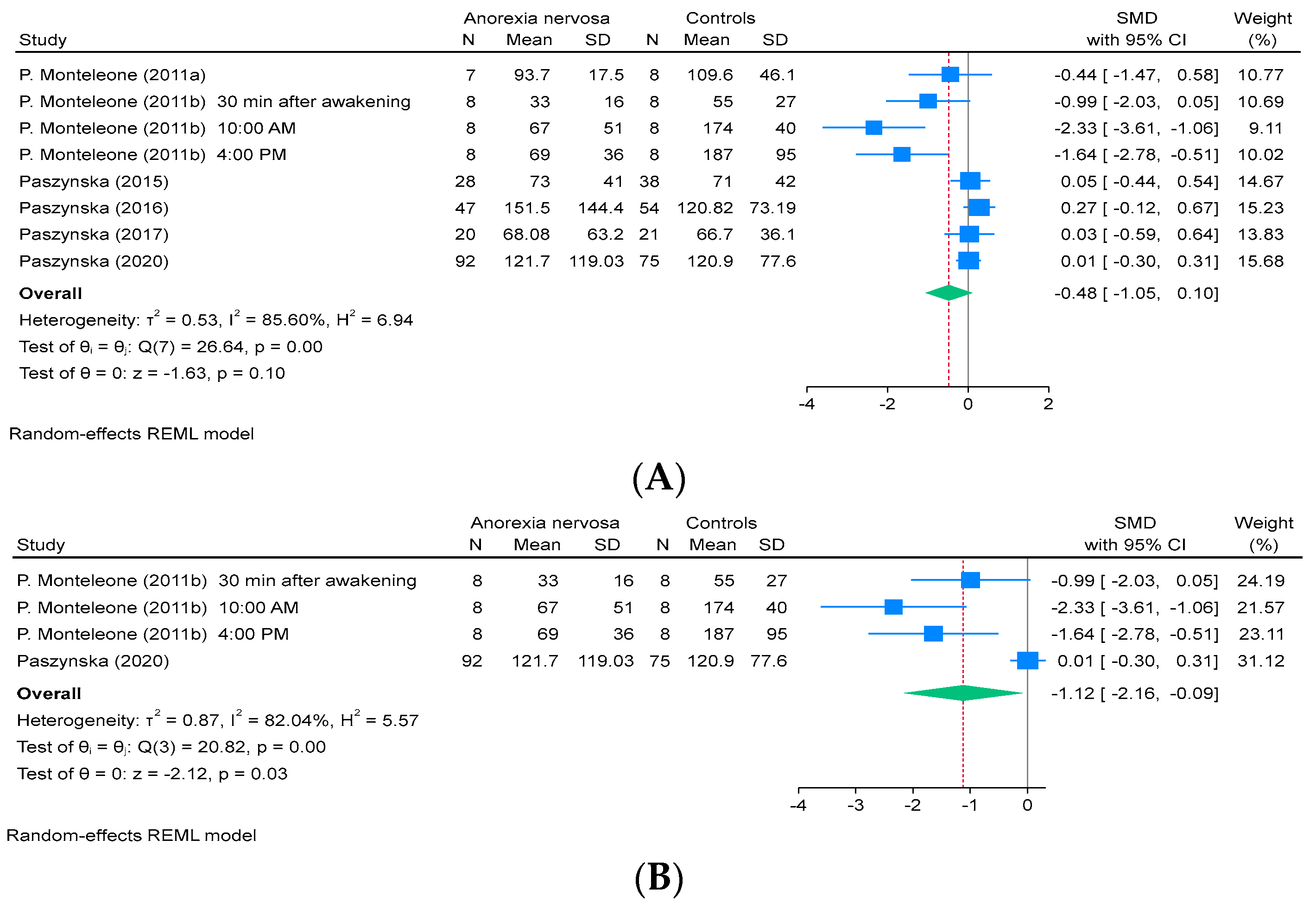

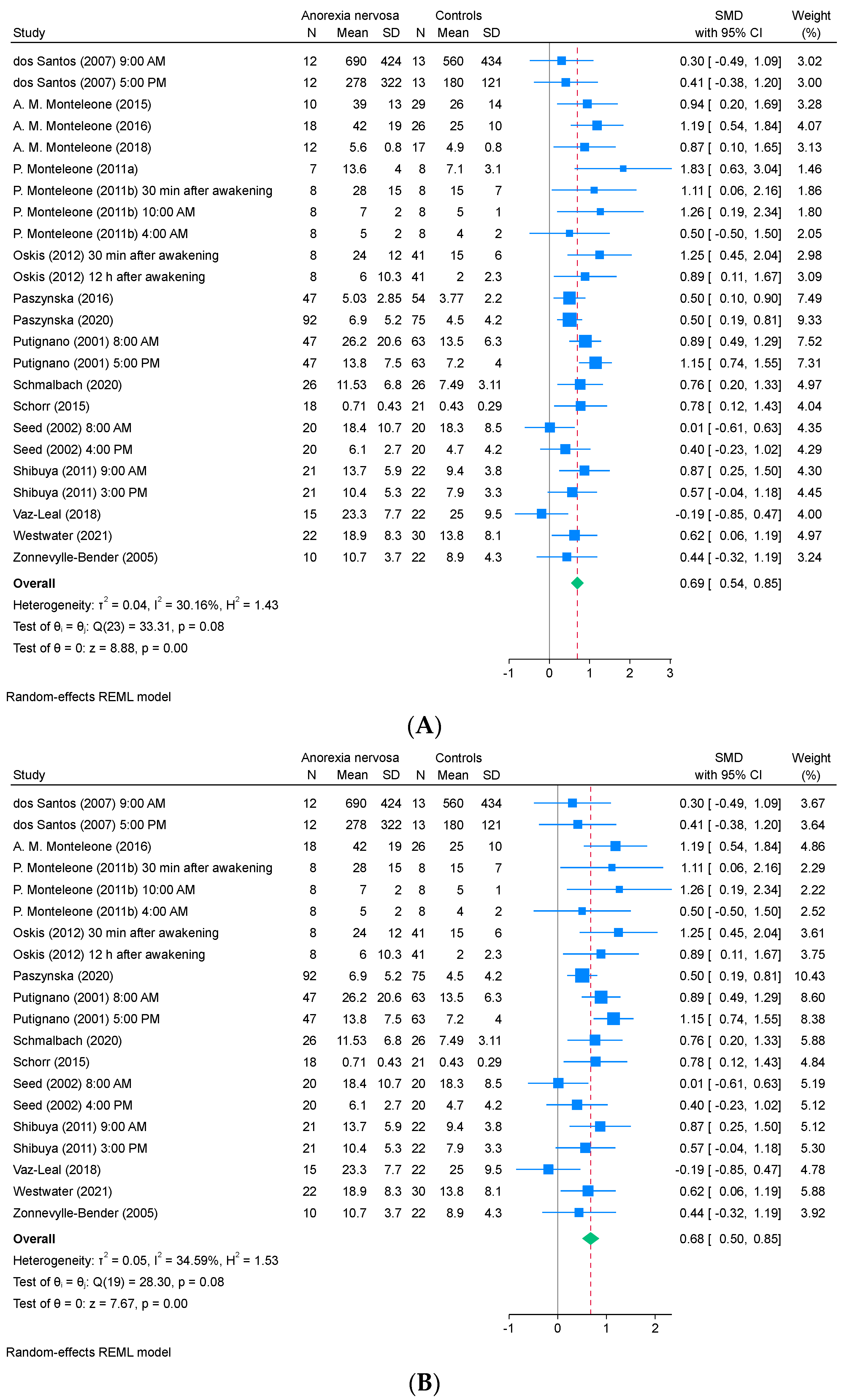

3.3. Meta-Analysis

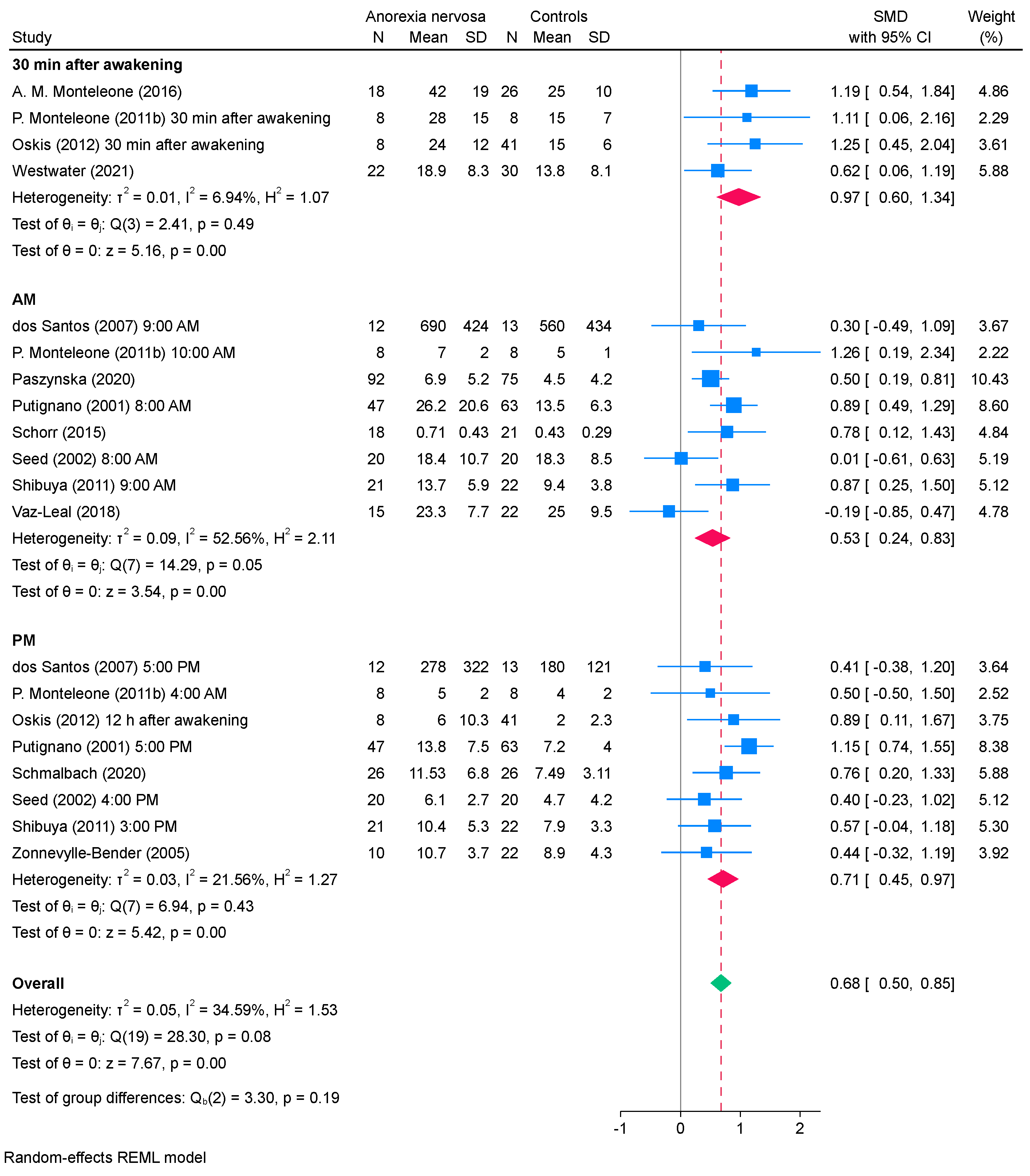

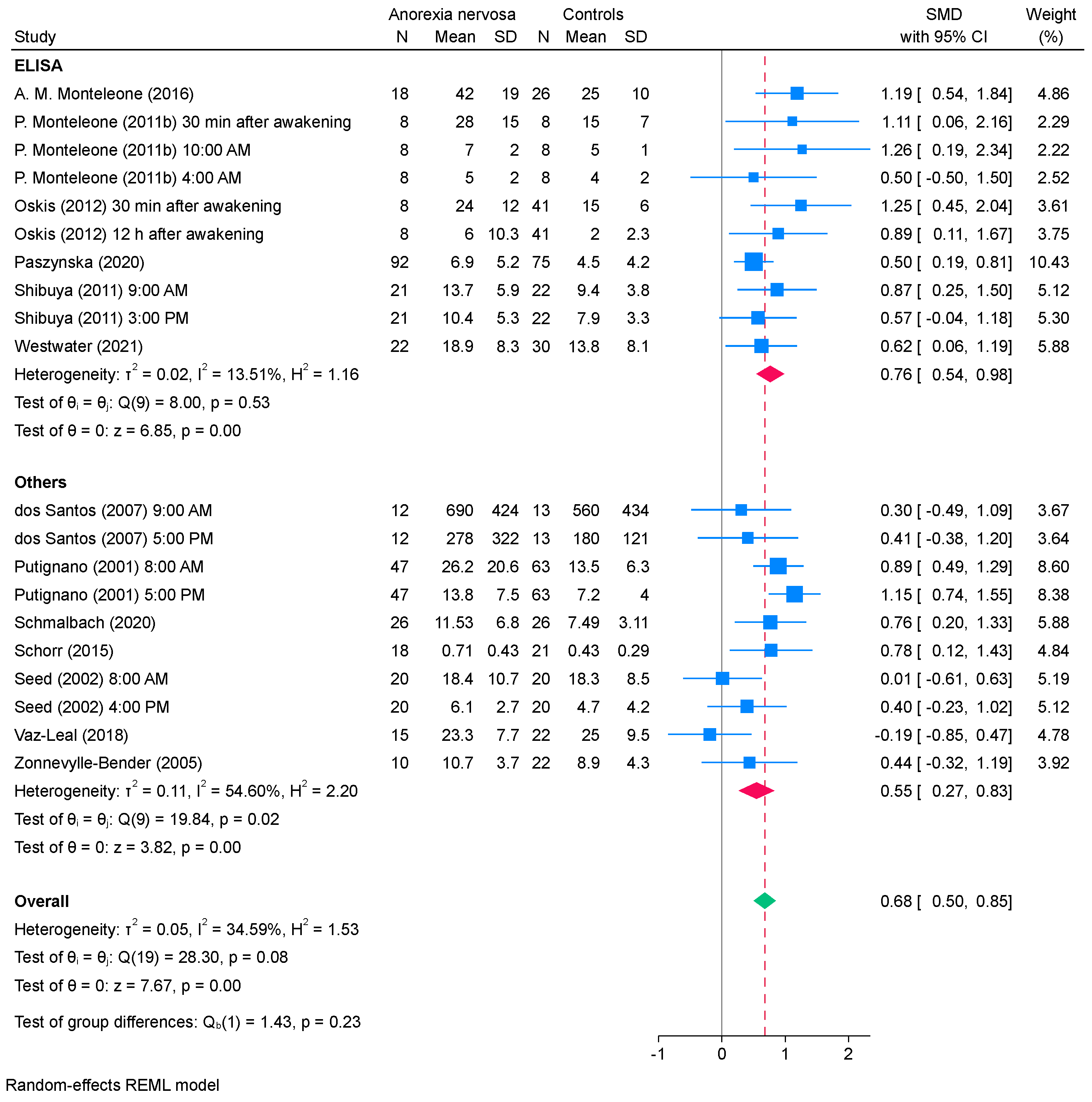

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.5. Meta-Regression Analysis

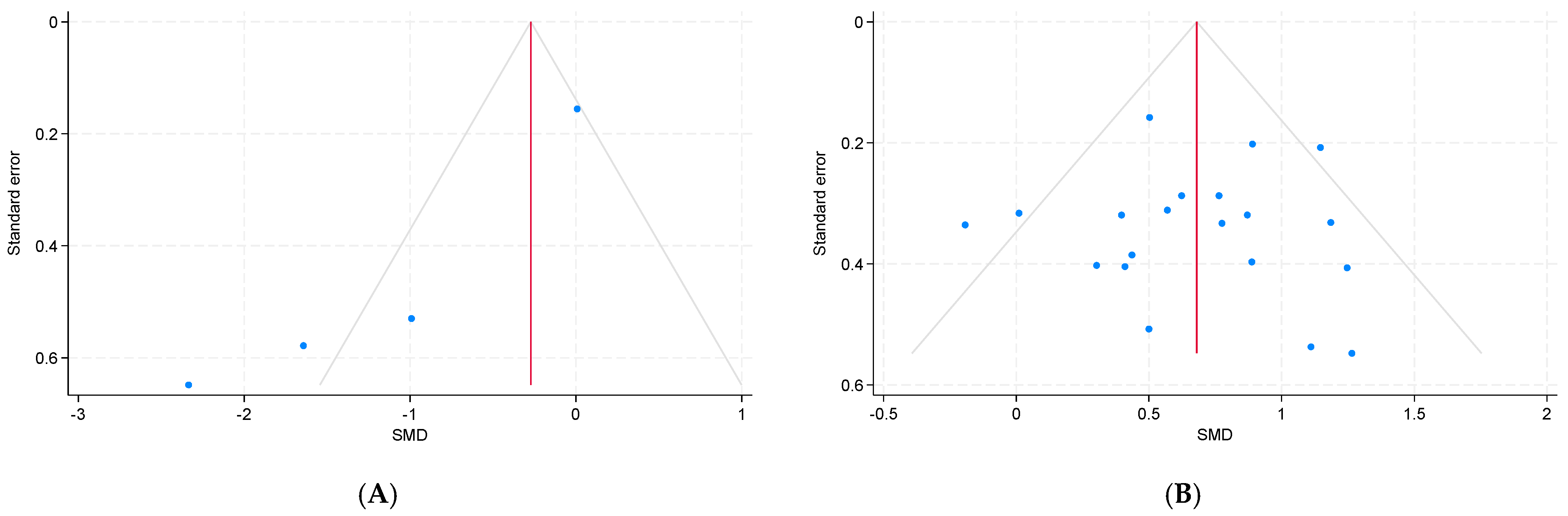

3.6. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AN | anorexia nervosa |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BN | bulimia nervosa |

| CI | confidence interval |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EIA | enzyme immunoassay |

| HPA | hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| LC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| LIA | line immunoassay |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| REML | restricted maximum likelihood |

| RIA | radioimmunoassay |

| SAM | sympatho-adrenomedullary |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SE | standard error |

| SMD | standardized Mean Difference |

References

- Abbate-Daga, G., Buzzichelli, S., Amianto, F., Rocca, G., Marzola, E., McClintock, S. M., & Fassino, S. (2011). Cognitive flexibility in verbal and nonverbal domains and decision making in anorexia nervosa patients: A pilot study. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, E. K., & Kumari, M. (2009). Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(10), 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, R. S., Lee, Y. J., Choi, J. Y., Kwon, H. B., & Chun, S. I. (2007). Salivary cortisol and DHEA levels in the Korean population: Age-related differences, diurnal rhythm, and correlations with serum levels. Yonsei Medical Journal, 48(3), 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baid, S. K., Sinaii, N., Wade, M., Rubino, D., & Nieman, L. K. (2007). Radioimmunoassay and tandem mass spectrometry measurement of bedtime salivary cortisol levels: A comparison of assays to establish hypercortisolism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 92(8), 3102–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, C. L., Su, J., Hlynsky, J. A., Goldner, E. M., & Gao, M. (2005). The mortality rate from anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38(2), 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casiero, D., & Frishman, W. H. (2006). Cardiovascular complications of eating disorders. Cardiology in Review, 14(5), 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, F., Barbot, M., Zilio, M., Ferasin, S., De Lazzari, P., Lizzul, L., Boscaro, M., & Scaroni, C. (2015). Age and the metabolic syndrome affect salivary cortisol rhythm: Data from a community sample. Hormones, 14(3), 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnowska, S., Ptaszyńska-Sarosiek, I., Kępka, A., Knaś, M., & Waszkiewicz, N. (2021). Salivary biomarkers of stress, anxiety and depression. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(3), 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, W. F., Moreira, R. O., Spagnol, C., & Appolinario, J. C. (2007). Does binge eating disorder alter cortisol secretion in obese women? Eating Behaviors, 8(1), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbert, K. M., Racine, S. E., & Klump, K. L. (2015). Research review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders—A synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 56(11), 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, B., Bartholdy, S., Robinson, L., Solmi, M., Ibrahim, M. A. A., Breen, G., Schmidt, U., & Himmerich, H. (2018). A meta-analysis of cytokine concentrations in eating disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 103, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, P. e. V., Grégio, A. M., Machado, M. A., de Lima, A. A., & Azevedo, L. R. (2008). Saliva composition and functions: A comprehensive review. Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 9(3), 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dedovic, K., Duchesne, A., Andrews, J., Engert, V., & Pruessner, J. C. (2009). The brain and the stress axis: The neural correlates of cortisol regulation in response to stress. Neuroimage, 47(3), 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, E., dos Santos, J. E., Ribeiro, R. P., Rosa E Silva, A. C., Moreira, A. C., & Silva de Sá, M. F. (2007). Absence of circadian salivary cortisol rhythm in women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 20(1), 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drevon, D., Fursa, S. R., & Malcolm, A. L. (2017). Intercoder reliability and validity of WebPlotDigitizer in extracting graphed data. Behavior Modification, 41(2), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easton, A., Meerlo, P., Bergmann, B., & Turek, F. W. (2004). The suprachiasmatic nucleus regulates sleep timing and amount in mice. Sleep, 27(7), 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, V., Vogel, S., Efanov, S. I., Duchesne, A., Corbo, V., Ali, N., & Pruessner, J. C. (2011). Investigation into the cross-correlation of salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase responses to psychological stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(9), 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galusca, B., Prévost, G., Germain, N., Dubuc, I., Ling, Y., Anouar, Y., Estour, B., & Chartrel, N. (2015). Neuropeptide Y and α-MSH circadian levels in two populations with low body weight: Anorexia nervosa and constitutional thinness. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0122040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, N., Galusca, B., Grouselle, D., Frere, D., Billard, S., Epelbaum, J., & Estour, B. (2010). Ghrelin and obestatin circadian levels differentiate bingeing-purging from restrictive anorexia nervosa. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology Metabolism, 95(6), 3057–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D., Workman, C., & Mehler, P. S. (2019). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 42(2), 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T. F., & Hasan, H. (2011). Anorexia nervosa: A unified neurological perspective. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 8(8), 679–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellhammer, D. H., Wüst, S., & Kudielka, B. M. (2009). Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(2), 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkelmann, K., Botzenhardt, J., Muhtz, C., Agorastos, A., Wiedemann, K., Kellner, M., & Otte, C. (2012). Sex differences of salivary cortisol secretion in patients with major depression. Stress, 15(1), 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkelmann, K., Moritz, S., Botzenhardt, J., Riedesel, K., Wiedemann, K., Kellner, M., & Otte, C. (2009). Cognitive impairment in major depression: Association with salivary cortisol. Biological Psychiatry, 66(9), 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiess, W., Meidert, A., Dressendörfer, R. A., Schriever, K., Kessler, U., König, A., Schwarz, H. P., & Strasburger, C. J. (1995). Salivary cortisol levels throughout childhood and adolescence: Relation with age, pubertal stage, and weight. Pediatric Research, 37(4), 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knorr, U., Vinberg, M., Kessing, L. V., & Wetterslev, J. (2010). Salivary cortisol in depressed patients versus control persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(9), 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukoubanis, K., Stefanaki, K., Karagiannakis, D. S., Kalampalikis, A., & Michala, L. (2023). Comparison of salivary cortisol levels between women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and healthy women: A pilot study. Endocrine, 82(2), 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, P. J., Vrang, N., Møller, M., Jessop, D. S., Lightman, S. L., Chowdrey, H. S., & Mikkelsen, J. D. (1994). The diurnal expression of genes encoding vasopressin and vasoactive intestinal peptide within the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus is influenced by circulating glucocorticoids. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research, 27(2), 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, E. A., Holsen, L. M., Desanti, R., Santin, M., Meenaghan, E., Herzog, D. B., Goldstein, J. M., & Klibanski, A. (2013). Increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal drive is associated with decreased appetite and hypoactivation of food-motivation neurocircuitry in anorexia nervosa. European Journal of Endocrinology, 169(5), 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A., Jang, S., Kim, J., Jang, J., Kim, I., Lee, S., & Seok, J. (2023). A-030 indicators generated from salivary cortisol measurement to assess circadian rhythm: Comparison of immunoassay and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry, 69(Suppl. 1), hvad097-029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingström, P., & Moynihan, P. (2003). Nutrition, saliva, and oral health. Nutrition, 19(6), 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, C., Izquierdo, A., Slattery, M., Becker, K. R., Plessow, F., Thomas, J. J., Eddy, K. T., Lawson, E. A., & Misra, M. (2020). Changes in appetite-regulating hormones following food intake are associated with changes in reported appetite and a measure of hedonic eating in girls and young women with anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 113, 104556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A. M., Monteleone, P., Serino, I., Amodio, R., Monaco, F., & Maj, M. (2016). Underweight subjects with anorexia nervosa have an enhanced salivary cortisol response not seen in weight restored subjects with anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 70, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A. M., Monteleone, P., Serino, I., Scognamiglio, P., Di Genio, M., & Maj, M. (2015). Childhood trauma and cortisol awakening response in symptomatic patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(6), 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A. M., Patriciello, G., Ruzzi, V., Cimino, M., Giorno, C. D., Steardo, L., Monteleone, P., & Maj, M. (2018). Deranged emotional and cortisol responses to a psychosocial stressor in anorexia nervosa women with childhood trauma exposure: Evidence for a “maltreated ecophenotype”? Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P., Scognamiglio, P., Canestrelli, B., Serino, I., Monteleone, A. M., & Maj, M. (2011a). Asymmetry of salivary cortisol and α-amylase responses to psychosocial stress in anorexia nervosa but not in bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, P., Scognamiglio, P., Monteleone, A. M., Mastromo, D., Steardo, L., Jr., Serino, I., & Maj, M. (2011b). Abnormal diurnal patterns of salivary α-amylase and cortisol secretion in acute patients with anorexia nervosa. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry: The Official Journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, 12(6), 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M. L., Harrison, M. E., Isserlin, L., Robinson, A., Feder, S., & Sampson, M. (2016). Gastrointestinal complications associated with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(3), 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskis, A., Loveday, C., Hucklebridge, F., Thorn, L., & Clow, A. (2012). Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol and DHEA in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Stress, 15(6), 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. R., Li, T. Y., Tucker, D., & Chen, K. Y. (2022). Pregnancy outcomes in women with active anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, J. J., Franco, C., Sodano, R., Freidenberg, B., Gordis, E., Anderson, D. A., Forsyth, J. P., Wulfert, E., & Frye, C. A. (2010). Sex differences in salivary cortisol in response to acute stressors among healthy participants, in recreational or pathological gamblers, and in those with posttraumatic stress disorder. Hormones and Behavior, 57(1), 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E., Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M., Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M., & Slopien, A. (2016). Salivary alpha-amylase, secretory IgA and free cortisol as neurobiological components of the stress response in the acute phase of anorexia nervosa. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 17(4), 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E., Roszak, M., Slopien, A., Boucher, Y., Dutkiewicz, A., Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M., Gawriolek, M., Otulakowska-Skrzynska, J., Rzatowski, S., & Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M. (2020). Is there a link between stress and immune biomarkers and salivary opiorphin in patients with a restrictive-type of anorexia nervosa? The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 21(3), 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paszynska, E., Schlueter, N., Slopien, A., Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M., Dyszkiewicz-Konwinska, M., & Hannig, C. (2015). Salivary enzyme activity in anorexic persons—A controlled clinical trial. Clinical Oral Investigations, 19(8), 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszynska, E., Slopien, A., Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M., & Hannig, C. (2017). Enzyme activities in parotid saliva of patients with the restrictive type of anorexia nervosa. Archives of Oral Biology, 76, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J. C., Wolf, O. T., Hellhammer, D. H., Buske-Kirschbaum, A., von Auer, K., Jobst, S., Kaspers, F., & Kirschbaum, C. (1997). Free cortisol levels after awakening: A reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sciences, 61(26), 2539–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putignano, P., Dubini, A., Toja, P., Invitti, C., Bonfanti, S., Redaelli, G., Zappulli, D., & Cavagnini, F. (2001). Salivary cortisol measurement in normal-weight, obese and anorexic women: Comparison with plasma cortisol. European Journal of Endocrinology, 145(2), 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M. E., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. L. (2010). Exploring the neurocognitive signature of poor set-shifting in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(14), 964–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohleder, N., Nater, U. M., Wolf, J. M., Ehlert, U., & Kirschbaum, C. (2004). Psychosocial stress-induced activation of salivary alpha-amylase: An indicator of sympathetic activity? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1032, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmalbach, I., Herhaus, B., Pässler, S., Runst, S., Berth, H., Wolff-Stephan, S., & Petrowski, K. (2020). Cortisol reactivity in patients with anorexia nervosa after stress induction. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorr, M., Lawson, E. A., Dichtel, L. E., Klibanski, A., & Miller, K. K. (2015). Cortisol measures across the weight spectrum. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 100(9), 3313–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorr, M., & Miller, K. K. (2017). The endocrine manifestations of anorexia nervosa: Mechanisms and management. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 13(3), 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, J. A., McCue, P. M., Wesnes, K. A., Dahabra, S., & Young, A. H. (2002). Basal activity of the HPA axis and cognitive function in anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 5(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, I., Nagamitsu, S., Okamura, H., Komatsu, H., Ozono, S., Yamashita, Y., & Matsuishi, T. (2011). Changes in salivary cortisol levels as a prognostic predictor in children with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 82(2), 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahler, J., Mueller, A., Rosenloecher, F., Kirschbaum, C., & Rohleder, N. (2010). Salivary alpha-amylase stress reactivity across different age groups. Psychophysiology, 47(3), 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, N., Yamaguchi, M., Aragaki, T., Eto, K., Uchihashi, K., & Nishikawa, Y. (2004). Effect of psychological stress on the salivary cortisol and amylase levels in healthy young adults. Archives of Oral Biology, 49(12), 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavaraputta, S., Ungprasert, P., Witchel, S. F., & Fazeli, P. K. (2023). Anorexia nervosa and adrenal hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Endocrinology, 189(3), S64–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Leal, F. J., Ramos-Fuentes, M. I., Rodríguez-Santos, L., Chimpén-López, C., Fernández-Sánchez, N., Zamora-Rodríguez, F. J., Beato-Fernández, L., Rojo-Moreno, L., & Guisado-Macías, J. A. (2018). Blunted cortisol response to stress in patients with eating disorders: Its association to bulimic features. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(3), 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vreeburg, S. A., Zitman, F. G., van Pelt, J., Derijk, R. H., Verhagen, J. C. M., van Dyck, R., Hoogendijk, W. J. G., Smit, J. H., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2010). Salivary cortisol levels in persons with and without different anxiety disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(4), 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, E. D., Fukushima, D., Nogeire, C., Roffwarg, H., Gallagher, T. F., & Hellman, L. (1971). Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 33(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwater, M. L., Mancini, F., Shapleske, J., Serfontein, J., Ernst, M., Ziauddeen, H., & Fletcher, P. C. (2021). Dissociable hormonal profiles for psychopathology and stress in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 51(16), 2814–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q., Zeng, Y., Gu, Y., Li, Z., Zhang, T., Yuan, B., Wang, T., Yan, J., Qin, H., Yang, L., Chen, X., Vidal-Puig, A., & Xu, Y. (2022). Time-restricted feeding entrains long-term behavioral changes through the IGF2-KCC2 pathway. iScience, 25(5), 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zonnevylle-Bender, M. J. S., van Goozen, S. H. M., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Jansen, L. M. C., van Elburg, A., & Engeland, H. (2005). Adolescent anorexia nervosa patients have a discrepancy between neurophysiological responses and self-reported emotional arousal to psychosocial stress. Psychiatry Research, 135(1), 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Author, Publication Year | Gender | Sample | N | Age | BMI | Duration of Illness | Biomarker of Interest | Measurement Method | Collection Time | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dos Santos et al. (2007) | Female | AN HC | 12 13 | 19.5 (median) 21.0 (median) | 15.6 (median) 21.4 (median) | NR | Cortisol | RIA | 9:00 AM, 5:00 PM, and 11:00 PM | 8 |

| 2 | A. M. Monteleone et al. (2015) | Female | Non-maltreated women with AN HC | 10 29 | 27.3 ± 10.0 27.6 ± 6.7 | 17.0 ± 1.3 21.5 ± 2.8 | NR | Cortisol | ELISA | Awakening and 15, 30, and 60 min after awakening | 8 |

| 3 | A. M. Monteleone et al. (2016) | Female | Underweight women with AN HC | 18 26 | 26.9 ± 5.6 26.3 ± 5.6 | 16.1 ± 1.7 20.9 ± 2.7 | NR | Cortisol | ELISA | Awakening and 15, 30, and 60 min after awakening | 8 |

| 4 | A. M. Monteleone et al. (2018) | Female | Non-maltreated woman with AN HC | 12 17 | 23.33 ± 5.2 26.00 ± 2.5 | 16.88 ± 1.5 21.86 ± 2.5 | 4.67 ± 3.47 years | Cortisol | ELISA | Between 2:30 PM and 4:30 PM | 8 |

| 5 | P. Monteleone et al. (2011a) | Female | AN HC | 7 8 | 20.2 ± 2.2 23.6 ± 2.2 | 16.3 ± 1.2 21.1 ± 2.4 | 5.8 ± 4.2 year | Alpha-amylase, Cortisol | ELISA | Between 3:30 PM and 5:00 PM | 7 |

| 6 | P. Monteleone et al. (2011b) | Female | AN HC | 8 8 | 21.6 ± 3.6 25.5 ± 4.5 | 17.2 ± 1.5 20.5 ± 1.9 | NR | Alpha-amylase, Cortisol | ELISA | Awakening and 15, 30, and 60 min after awakening, 10:00 AM, 12:00 PM, 4:00 PM, 6:00 PM, 7:00 PM, and 8:00 PM | 8 |

| 7 | Oskis et al. (2012) | Female | AN HC | 8 41 | 15.13 ± 1.64 15.46 ± 1.53 | 18.56 ± 1.09 22.05 ± 3.54 | NR | Cortisol | ELISA | Awakening and 30 min, and 12 h after awakening | 7 |

| 8 | Paszynska et al. (2015) | Female | AN HC | 28 38 | 15 ± 2 14 ± 1 | NR | 1.2 ± 0.6 years | Alpha-amylase | Colorimetric assay | Between 9:00 AM and 12:00 PM | 9 |

| 9 | Paszynska et al. (2016) | Female | AN HC | 47 54 | 15 ± 2 15 ± 2 | 14.18 ± 1.31 19.96 ± 1.33 | 11 ± 5 months | Alpha-amylase, Cortisol | ELISA | Between 9:00 AM and 11:00 AM | 9 |

| 10 | Paszynska et al. (2017) | Female | AN HC | 20 21 | 15 ± 2 16 ± 2 | 14.09 ± 1.3 20.00 ± 1.5 | 14 ± 9 months | Alpha-amylase | Colorimetric assay | Between 9:00 AM and 12:00 PM | 8 |

| 11 | Paszynska et al. (2020) | Female | AN HC | 92 75 | 15.02 ± 2.4 15.4 ± 2.3 | 14.3 ± 1.4 19.8 ± 1.7 | 10.5 ± 6 months | Alpha-amylase, Cortisol | ELISA | Between 9:00 AM and 10:00 AM | 10 |

| 12 | Putignano et al. (2001) | Female | Untreated AN HC | 47 63 | 23.0 ± 6.3 31.2 ± 10.2 | 13.7 ± 2.26 20.8 ± 2.14 | NR | Cortisol | RIA | 8:00 AM, 5:00 PM, and 12:00 AM | 8 |

| 13 | Schmalbach et al. (2020) | Both | AN HC | 26 26 | 26.5 ± 6.1 25.0 ± 5.3 | 19.3 ± 3.4 23.08 ± 3.3 | NR | Cortisol | LIA | Between 2:00 PM and 4:00 PM | 10 |

| 14 | Schorr et al. (2015) | Female | AN HC | 18 21 | 26 ± 6 27 ± 7 | 18.2 ± 1.0 22.3 ± 1.4 | NR | Cortisol | EIA | 7:00 AM | 7 |

| 15 | Seed et al. (2002) | Female | AN HC | 20 20 | 29.1 ± 8.4 29.3 ± 8.6 | 14.2 ± 2.1 22.4 ± 3.1 | NR | Cortisol | RIA | 8:00 AM, 12:00 PM, 4:00 PM, and 8:00 PM | 8 |

| 16 | Shibuya et al. (2011) | Female | AN before inpatient treatment HC | 21 22 | 14.4 ± 1.4 14.0 ± 1.2 | 13.0 ± 1.5 19.3 ± 2.1 | 11.0 ± 9.7 months | Cortisol | ELISA | 9:00 AM, 11:00 AM, 1:00 PM, 3:00 PM, 5:00 PM, and 7:00 PM | 8 |

| 17 | Vaz-Leal et al. (2018) | Female | AN HC | 15 22 | 22.0 ± 3.6 21.7 ± 2.3 | 16.7 ± 0.8 21.6 ± 1.1 | 4.9 ± 2.5 years | Cortisol | RIA | 8:00 AM | 8 |

| 18 | Westwater et al. (2021) | Female | AN HC | 22 30 | 24.6 ± 4.7 23.9 ± 3.5 | 16.4 ± 1.4 21.9 ± 2.1 | 9.0 ± 5.8 years | Cortisol | ELISA | Awakening and 30, 45, and 60 min after awakening | 11 |

| 19 | Zonnevylle-Bender et al. (2005) | Female | AN HC | 10 22 | 15.5 ± 1.8 14.9 ± 1.1 | 16.2 ± 1.2 NR | 7–15 months | Cortisol | RIA | Between 12:00 PM and 6:00 PM | 7 |

| Covariate | Reports | Coefficient | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20 | −0.005 | −0.41, 0.30 | 0.77 |

| BMI | 20 | 0.021 | −0.07, 1.50 | 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seura, T.; Nanba, Y. Evaluating Salivary Cortisol and Alpha-Amylase as Candidate Biomarkers in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120260

Seura T, Nanba Y. Evaluating Salivary Cortisol and Alpha-Amylase as Candidate Biomarkers in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(12):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120260

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeura, Takahiro, and Yuuna Nanba. 2025. "Evaluating Salivary Cortisol and Alpha-Amylase as Candidate Biomarkers in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 12: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120260

APA StyleSeura, T., & Nanba, Y. (2025). Evaluating Salivary Cortisol and Alpha-Amylase as Candidate Biomarkers in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(12), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120260