Job Demands and Resources as Predictors of Burnout Dimensions in Special Education Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Job Demands and Job Resources in the Teaching Profession

1.2. Risk Factors

1.3. Protective Factors

1.4. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Burnout Dimensions Correlates

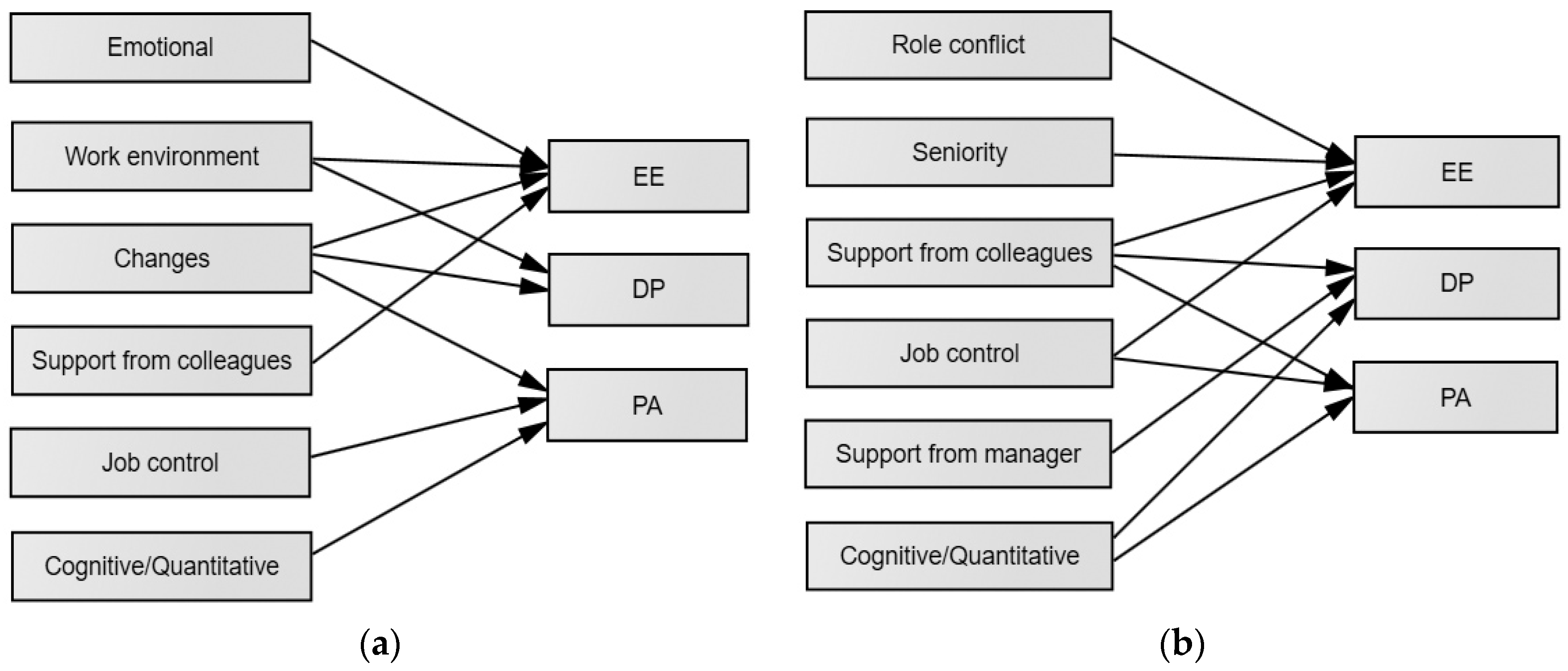

3.2. Models of Prediction

4. Discussion

4.1. Prediction of Job Burnout via the JD–R Model

4.1.1. Emotional Exhaustion

4.1.2. Depersonalisation

4.1.3. Personal Accomplishment

4.2. Demographic Variables

4.3. Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1. | Although depersonalisation is often replaced by the term cynicism (emphasising attitude toward work in general, not only toward people) in this paper we will use the original term, because among teachers, burnout is most often reflected in relationships with students, parents, and colleagues. |

| 2. | Due to lack of space, only significant differences are reported in the text. Contact the corresponding author for complete data concerning control variables. |

References

- Baka, Ł. (2015). Does job burnout mediate negative effects of job demands on mental and physical health in a group of teachers? International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 28(2), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands–Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, A., Evers, W. J. G., & Tomic, W. (2001). Self-efficacy in eliciting social support and burnout among secondary-school teachers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(7), 1474–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., & Lane, K. L. (2014). Special education teacher burnout: A synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(4), 681–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Silva, J., Peixoto, F., Galhoz, A., & Gaitas, S. (2023). Job demands and resources as predictors of well-being in Portuguese teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, M. M., O’Brien, K. M., Brunsting, N. C., & Bettini, E. (2021). Special educators’ working conditions, self-efficacy, and practice use with students with emotional/behavioral disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 42(4), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands–resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stasio, S., Fiorilli, C., Benevene, P., Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L., & Chiacchio, C. D. (2017). Burnout in special needs teachers at kindergarten and primary school: Investigating the role of personal resources and work wellbeing. Psychology in the Schools, 54(5), 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobac, A., & Micic, I. (2025). Burnout syndrome among special education teachers at schools for children with disabilities in the Republic of Serbia: Challenges and risk factors. Journal of Educational Research and Instruction, 56(2), 365–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C., & Murphy, M. (2015). Burnout in Irish teachers: Investigating the role of individual differences, work environment and coping factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 50, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C. (2001). Inclusion: Identifying potential stressors for regular class teachers. Educational Research, 43(3), 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwood, J. D., Werts, M. G., & Varghese, C. (2018). Mixed-methods analysis of rural special educators’ role stressors, behavior management, and burnout. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37(1), 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hlado, P., & Harvankova, K. (2024). Teachers’ perceived work ability: A qualitative exploration using the Job Demands–Resources model. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlado, P., Juhan, L., & Harvankova, K. (2025). Antecedents of perceived teacher work ability: A comprehensive model across work and non-work domains. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1557456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J. Y., Liao, P. W., & Lee, Y. H. (2022). Teacher motivation and relationships within school contexts as drivers of urban teacher efficacy in Taipei City. Asia-Pacific Education Research, 31, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V., Karić, J., Mihajlović, G., Džamonja-Ignjatović, T., & Hinić, D. (2019). Work-related burnout syndrome in special education teachers working with children with developmental disorders: Possible correlations with some socio-demographic aspects and assertiveness. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(5), 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V. R., Hinić, D., Džamonja-Ignjatović, T., Stamatović Gajić, B., Gajić, G., & Mihajlović, G. (2021). Individual-psychological factors and perception of social support in burnout syndrome. Vojnosanitetski Pregled, 78(9), 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketheeswarani, K. (2018). Job satisfaction of teachers attached to the special education units in regular schools in Sri Lanka. European Journal of Special Education Research, 3(1), 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmousi, N., & Alexopoulos, E. C. (2016). Stress sources and manifestations in a nationwide sample of pre-primary, primary, and secondary educators in Greece. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüksüleymanoğlu, R. (2011). Burnout syndrome levels of teachers in special education schools in Turkey. International Journal of Special Education, 26(1), 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Maslach burnout inventory manual (4th ed.). Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2022). The burnout challenge: Managing people’s relationships with their jobs. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. (2022). National report on inclusive education in the Republic of Serbia. Ministry of Education.

- Mitchell, D. (2014). What really works in special and inclusive education: Using evidence-based strategies. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, E., & Takács, I. (2017). The road to teacher burnout and its possible protecting factors: A narrative review. Review of Social Sciences, 2(8), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, Y. (2007). The role of classroom management efficacy in predicting teacher burnout. International Journal of Social Sciences, 2(4), 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Pakdee, S., Cheechang, P., Thammanoon, R., & Krobpet, S. (2025). Burnout and well-being among higher education teachers: Influencing factors of burnout. BMC Public Health, 25, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantić, N., & Čekić-Marković, J. (Eds.). (2012). Teachers in Serbia: Views on the profession and on educational reforms. Centre for Education Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, H. K., Goddard, R., & Wilss, L. A. (2005). Well-being, burnout and competence: Implications for teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 30(2), 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plichta, P. (2014). Occupational burdens in special educators working with intellectually disabled students. Medycyna Pracy, 65(2), 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, B., Jelić, D., Dinić, M. B., & Milinković, I. (2025). Measuring job demands and resources: Validation of the new Job Characteristics Questionnaire (JCQ). Psihologija, 58(2), 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radošević, V., Jelić, D., Matanović, J., & Popov, B. (2018). Job demands and resources as predictors of burnout and work engagement: Main and interaction effects. Primenjena Psihologija, 11(1), 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K. A. R., Hemphill, M. A., & Templin, T. J. (2018). Personal and contextual factors related to teachers’ experience with stress and burnout. Teachers and Teaching, 24(7), 768–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, S., Ghanizadeh, A., & Ghapanchi, Z. (2015). A study of contextual precursors of burnout among EFL teachers. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 4(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K., Hietajärvi, L., & Lonka, K. (2019). Work burnout and engagement profiles among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloviita, T., & Pakarinen, E. (2021). Teacher burnout explained: Teacher-, student-, and organization-level variables. Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2009). Does school context matter? Relations with teacher burnout and job satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(3), 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2016). Teacher stress and teacher self-efficacy as predictors of engagement, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. Creative Education, 7, 1785–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Social Psychology of Education, 21, 1251–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetackova, I., Viktorova, I., Pavlas Martanova, V., Pachova, A., Francova, V., & Stech, S. (2019). Teachers between job satisfaction and burnout syndrome: What makes difference in Czech elementary schools? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Haverinen, K., Jindal-Snape, D., & Kontu, E. (2019). Special education teachers’ experienced burnout and perceived fit with the professional community: A 5-year follow-up study. British Educational Research Journal, 45(3), 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillaci, M., & Hofmann, V. (2021). Working in inclusive or non-inclusive contexts: Relations between collaborative variables and special education teachers’ burnout. Frontiers in Education, 6, 640227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S., & Sebastine, A. J. (2023). Work–life balance, social support, and burnout: A quantitative study of social workers. Journal of Social Work, 23(6), 1135–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempien, L. R., & Loeb, R. C. (2002). Differences in job satisfaction between general education and special education teachers. Remedial and Special Education, 23(5), 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T. W., Leisink, P. L., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying occupational health theories to educator stress: Contribution of the job demands–resources model. In T. M. McIntyre, S. E. McIntyre, & D. J. Francis (Eds.), Educator stress: An occupational health perspective (pp. 237–259). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, K. K., & Kwong, T. L. (2016). Emotional experience of Caam2 in teaching: Power and interpretation of teachers’ work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2025). ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#129180281 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zeng, Y., Liu, Y., & Peng, J. (2024). Teacher self-efficacy as a mediator between school context and teacher burnout in developing regions. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 29(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SEN | GE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 102 (87.9%) | 122 (84.1%) |

| Male | 14 (12.1%) | 23 (15.9%) | |

| Education level | College of applied studies | 0 | 3 (2.1%) |

| Graduate studies | 105 (90.5%) | 126 (86.9%) | |

| Postgraduate studies | 11 (9.5%) | 16 (11.0%) | |

| Work contract | Indefinite employment | 90 (77.6%) | 102 (70.3%) |

| Fixed-term employment | 26 (22.4%) | 43 (29.7%) | |

| Marital status | Married/in a relationship | 77 (66.4%) | 87 (60.0%) |

| Single | 29 (25.0%) | 43 (29.7%) | |

| Other | 10 (8.6%) | 15 (10.4%) |

| Group | N | M | SD | Min/ Max | Skewn. | Kurt. | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive/ Quantitative demands | SEN | 116 | 3.69 | 0.63 | 2/5 | −0.218 | −0.068 | t(259) = −3.942 ** |

| GE | 145 | 3.99 | 0.59 | 2/5 | −0.524 | 0.651 | ||

| Emotional demands | SEN | 116 | 3.88 | 0.65 | 2/5 | −0.224 | −0.560 | t(259) = −2.382 * |

| GE | 145 | 4.06 | 0.57 | 2.7/5 | −0.335 | −0.372 | ||

| Physical demands | SEN | 116 | 2.61 | 0.99 | 1/5 | 0.250 | −0.593 | t(259) = 3.262 ** |

| GE | 145 | 2.26 | 0.73 | 1/4 | 0.068 | −0.760 | ||

| Job control | SEN | 116 | 3.43 | 0.63 | 2/5 | −0.104 | −0.495 | t(259) = 1.547 |

| GE | 145 | 3.32 | 0.51 | 2/4.5 | −0.344 | −0.382 | ||

| Support from managers | SEN | 116 | 3.78 | 0.94 | 1.2/5 | −0.600 | −0.330 | t(259) = −1.934 |

| GE | 145 | 3.98 | 0.79 | 2.5/5 | −0.432 | −0.609 | ||

| Support from colleagues | SEN | 116 | 3.78 | 0.77 | 1.5/5 | −0.374 | −0.136 | t(259) = −2.727 ** |

| GE | 145 | 4.02 | 0.62 | 2/5 | −0.572 | 0.309 | ||

| Role conflict | SEN | 116 | 2.60 | 0.49 | 1.6/4.2 | 0.159 | 0.191 | t(259) = 0.325 |

| GE | 145 | 2.58 | 0.50 | 1.4/3.6 | 0.209 | −0.412 | ||

| Changes | SEN | 116 | 2.37 | 0.80 | 1/4 | −0.020 | −1.16 | t(259) = −0.898 |

| GE | 145 | 2.45 | 0.63 | 1/4 | −0.121 | −0.502 | ||

| Work environment | SEN | 116 | 2.64 | 0.92 | 1/4.8 | 0.104 | −0.601 | t(259) = −0.464 |

| GE | 145 | 2.69 | 0.77 | 1/4.8 | −0.001 | −0.469 | ||

| Emotional exhaustion | SEN | 116 | 22.43 | 13.71 | 1/54 | 0.253 | −0.967 | t(259) = −0.015 |

| GE | 145 | 22.46 | 11.79 | 0/48 | 0.159 | −0.786 | ||

| Depersonalisation | SEN | 116 | 4.72 | 4.76 | 0/21 | 1.122 | 0.516 | t(259) = −1.384 |

| GE | 145 | 5.54 | 4.78 | 0/21 | 1.065 | 0.820 | ||

| Personal accomplishment | SEN | 116 | 38.53 | 7.19 | 18/48 | −0.632 | −0.304 | t(259) = 0.285 |

| GE | 145 | 38.28 | 6.55 | 16/48 | −0.968 | 1.06 |

| SEN Teachers | EE | DP | PA |

| Cognitive/Quantitative demands | 0.058 | −0.080 | 0.180 |

| Emotional demands | 0.402 ** | 0.190 * | −0.162 |

| Physical demands | 0.306 ** | 0.213 * | −0.124 |

| Job control | −0.405 ** | −0.284 ** | 0.404 ** |

| Support from managers | −0.606 ** | −0.362 ** | 0.345 ** |

| Support from colleagues | −0.527 ** | −0.407 ** | 0.376 ** |

| Role conflict | 0.443 ** | 0.396 ** | −0.208 * |

| Changes | 0.617 ** | 0.473 ** | −0.382 ** |

| Work environment | 0.485 ** | 0.382 ** | −0.252 ** |

| Age | 0.191 * | 0.086 | −0.041 |

| Seniority | 0.193 * | 0.072 | −0.044 |

| GE Teachers | EE | DP | PA |

| Cognitive/Quantitative demands | 0.212 * | 0.220 ** | 0.147 |

| Emotional demands | 0.257 ** | 0.068 | 0.007 |

| Physical demands | 0.279 ** | 0.202 * | −0.036 |

| Job control | −0.377 ** | −0.253 ** | 0.337 ** |

| Support from managers | −0.546 ** | −0.527 ** | 0.319 ** |

| Support from colleagues | −0.503 ** | −0.407 ** | 0.307 ** |

| Role conflict | 0.493 ** | 0.411 ** | −0.144 |

| Changes | 0.481 ** | 0.471 ** | −0.284 ** |

| Work environment | 0.449 ** | 0.295 ** | −0.265 ** |

| Age | 0.368 ** | 0.173 * | −0.084 |

| Seniority | 0.462 ** | 0.280 ** | −0.102 |

| SEN Teachers | EMO | PHY | CON | SM | SC | RC | CH | WE |

| Cognitive/Quantitative | 0.215 * | 0.364 ** | 0.036 | −0.048 | −0.030 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.161 |

| Emotional | 1 | 0.282 ** | −0.176 | −0.292 ** | −0.147 | 0.307 ** | 0.289 ** | 0.262 ** |

| Physical | 0.282 ** | 1 | −0.332 ** | −0.260 ** | −0.188 * | 0.388 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.510 ** |

| Job control | −0.176 | −0.332 ** | 1 | 0.484 ** | 0.485 ** | −0.303 ** | −0.388 ** | −0.372 ** |

| Support from managers | −0.292 ** | −0.260 ** | 0.484 ** | 1 | 0.723 ** | −0.537 ** | −0.820 ** | −0.415 ** |

| Support from colleagues | −0.147 | −0.188 * | 0.485 ** | 0.723 ** | 1 | −0.432 ** | −0.680 ** | −0.293 ** |

| Role conflict | 0.307 ** | 0.388 ** | −0.303 ** | −0.537 ** | −0.432 ** | 1 | 0.582 ** | 0.530 ** |

| Changes | 0.289 ** | 0.272 ** | −0.388 ** | −0.820 ** | −0.680 ** | 0.582 ** | 1 | 0.451 ** |

| Work environment | 0.262 ** | 0.510 ** | −0.372 ** | −0.415 ** | −0.293 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.451 ** | 1 |

| GE Teachers | EMO | PHY | CON | SM | SC | RC | CH | WE |

| Cognitive/Quantitative | 0.320 ** | 0.272 ** | −0.010 | −0.126 | −0.015 | 0.262 ** | 0.197 * | 0.220 ** |

| Emotional | 1 | 0.178 * | −0.183 * | −0.118 | 0.024 | 0.191 * | 0.281 ** | 0.392 ** |

| Physical | 0.178 * | 1 | −0.088 | −0.178 * | −0.159 | 0.334 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.373 ** |

| Job control | −0.183 * | −0.088 | 1 | 0.360 ** | 0.295 ** | −0.290 ** | −0.350 ** | −0.369 ** |

| Support from managers | −0.118 | −0.178 * | 0.360 ** | 1 | 0.628 ** | −0.566 ** | −0.704 ** | −0.502 ** |

| Support from colleagues | 0.024 | −0.159 | 0.295 ** | 0.628 ** | 1 | −0.368 ** | −0.434 ** | −0.310 ** |

| Role conflict | 0.191 * | 0.334 ** | −0.290 ** | −0.566 ** | −0.368 ** | 1 | 0.564 ** | 0.497 ** |

| Changes | 0.281 ** | 0.313 ** | −0.350 ** | −0.704 ** | −0.434 ** | 0.564 ** | 1 | 0.541 ** |

| Work environment | 0.392 ** | 0.373 ** | −0.369 ** | −0.502 ** | −0.310 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.541 ** | 1 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | −1.480 | 10.089 | −0.147 | 0.884 | |

| Emotional | 4.698 | 1.487 | 0.224 | 3.159 | 0.002 |

| Work environment | 3.370 | 1.129 | 0.227 | 2.984 | 0.003 |

| Changes | 5.079 | 1.709 | 0.296 | 2.973 | 0.004 |

| Support from colleagues | −4.026 | 1.627 | −0.226 | −2.475 | 0.015 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | −3.491 | 1.373 | −2.543 | 0.012 | |

| Changes | 2.249 | 0.540 | 0.378 | 4.165 | 0.000 |

| Work environment | 1.093 | 0.469 | 0.211 | 2.332 | 0.021 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 25.374 | 5.465 | 4.643 | 0.000 | |

| Changes | −2.567 | 0.797 | −0.286 | −3.222 | 0.002 |

| Job control | 3.248 | 1.004 | 0.286 | 3.234 | 0.002 |

| Cognitive/ Quantitative demands | 2.196 | 0.938 | 0.191 | 2.340 | 0.021 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 29.954 | 9.289 | 3.225 | 0.002 | |

| Support from colleagues | −5.098 | 1.298 | −0.268 | −3.927 | 0.000 |

| Role conflict | 7.117 | 1.579 | 0.302 | 4.507 | 0.000 |

| Seniority | 0.393 | 0.081 | 0.310 | 4.832 | 0.000 |

| Job control | −3.290 | 1.537 | −0.141 | −2.140 | 0.034 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 2.731 | 3.806 | 0.718 | 0.474 | |

| Changes | 2.469 | 0.605 | 0.328 | 4.078 | 0.000 |

| Support from colleagues | −2.023 | 0.607 | −0.263 | −3.334 | 0.001 |

| Cognitive/ Quantitative demands | 1.224 | 0.584 | 0.152 | 2.096 | 0.038 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 10.118 | 5.318 | 1.903 | 0.059 | |

| Job control | 3.509 | 1.033 | 0.270 | 3.397 | 0.001 |

| Support from colleagues | 2.426 | 0.841 | 0.230 | 2.884 | 0.005 |

| Cognitive/Quantitative | 1.701 | 0.842 | 0.154 | 2.019 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jovanović, V.R.; Miljević, Č.; Hinić, D.; Mitrović, D.; Vranješ, S.; Jakovljević, B.; Stanisavljević, S.; Jovčić, L.; Jugović, K.P.; Simić, N.; et al. Job Demands and Resources as Predictors of Burnout Dimensions in Special Education Teachers. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120258

Jovanović VR, Miljević Č, Hinić D, Mitrović D, Vranješ S, Jakovljević B, Stanisavljević S, Jovčić L, Jugović KP, Simić N, et al. Job Demands and Resources as Predictors of Burnout Dimensions in Special Education Teachers. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(12):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120258

Chicago/Turabian StyleJovanović, Vesna R., Čedo Miljević, Darko Hinić, Dragica Mitrović, Slađana Vranješ, Biljana Jakovljević, Sanja Stanisavljević, Ljiljana Jovčić, Katarina Pavlović Jugović, Neda Simić, and et al. 2025. "Job Demands and Resources as Predictors of Burnout Dimensions in Special Education Teachers" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 12: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120258

APA StyleJovanović, V. R., Miljević, Č., Hinić, D., Mitrović, D., Vranješ, S., Jakovljević, B., Stanisavljević, S., Jovčić, L., Jugović, K. P., Simić, N., & Mihajlović, G. (2025). Job Demands and Resources as Predictors of Burnout Dimensions in Special Education Teachers. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(12), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120258