Youths’ Wellbeing Between Future and Uncertainty Across Cultural Contexts: A Focus on Latent Meanings as Mediational Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

Q1: Are there differences in wellbeing (measured by MHC-SF) and general distress (measured by DASS-21) between Armenian and Italian youth?

Q2: Does the intolerance of uncertainty negatively affect wellbeing?

Q3: Is a future orientation—positively defined as an expectation for upcoming opportunities, plans, and future objectives (Carstensen & Lang, 1996)—linked with higher levels of wellbeing?

Q4: Are societal sources of worry, such as war and the climate crisis, correlated with wellbeing and general distress of Armenian and Italian youth?

Q5: Do latent dimensions of sense (i.e., general meanings) mediate the relationships between levels of wellbeing and/or general distress and other measures (i.e., intolerance of uncertainty, future-oriented time perspective, worries about war and/or climate crisis)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures and Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- (1)

- through 3 (Semiotic cluster) × 2 (Group) ANOVAs and Chi-square test estimating the differences (Q1) in MHC-SF (including the prevalences of wellbeing diagnoses) and DASS-21 between Armenian and Italian participants. Additionally, as a function of national groups and semiotic clusters, differences were tested in all other measures. A further analysis examines the distribution of responses within the two populations regarding the items of the two self-report instruments used to identify worries about climate change and war.

- (2)

- Regression analyses were performed to explore the impact of (Q2) IUS-R, (Q3) FTP, (Q4) CCWS, and WEWS on wellbeing and distress.

- (3)

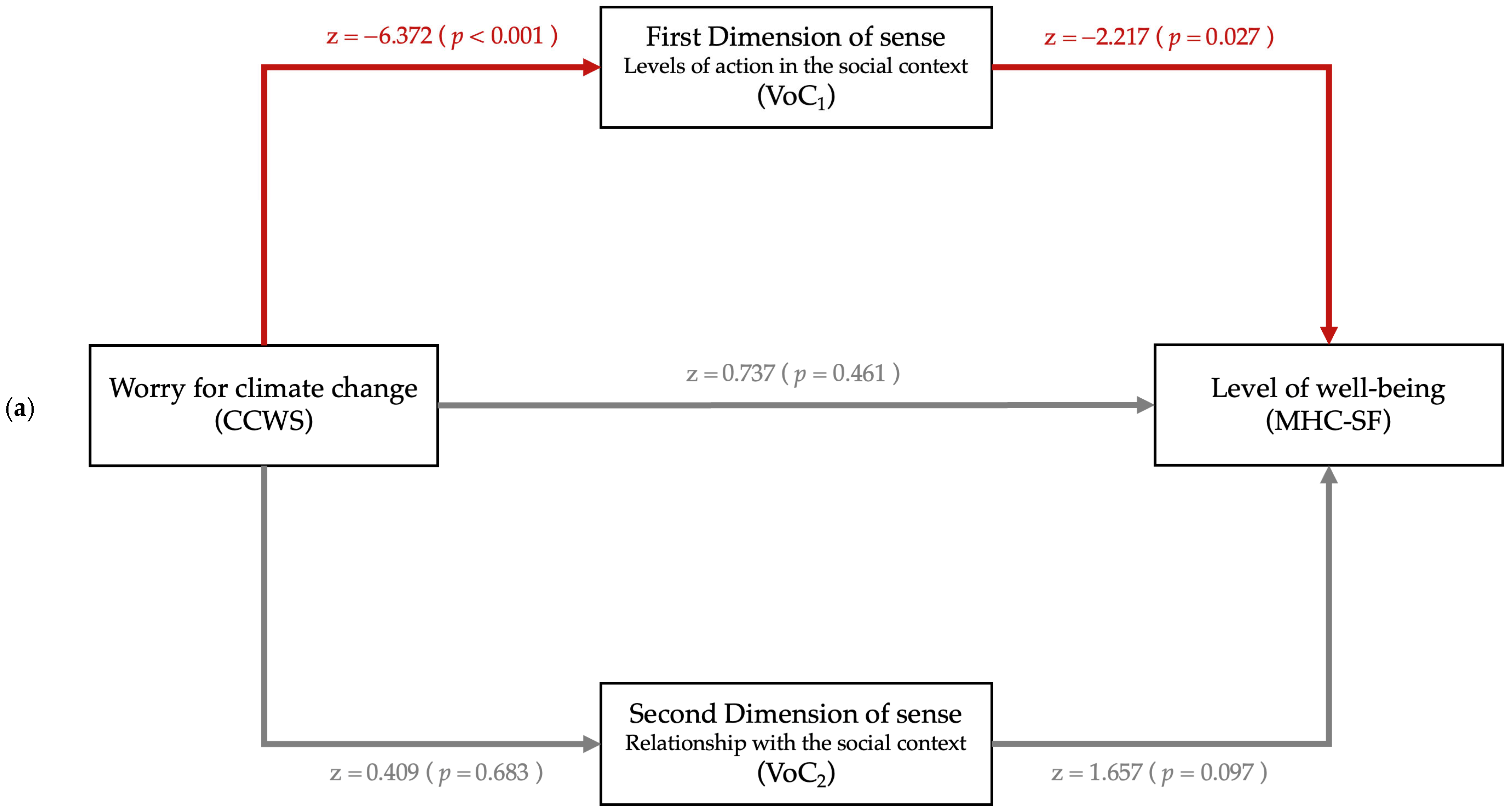

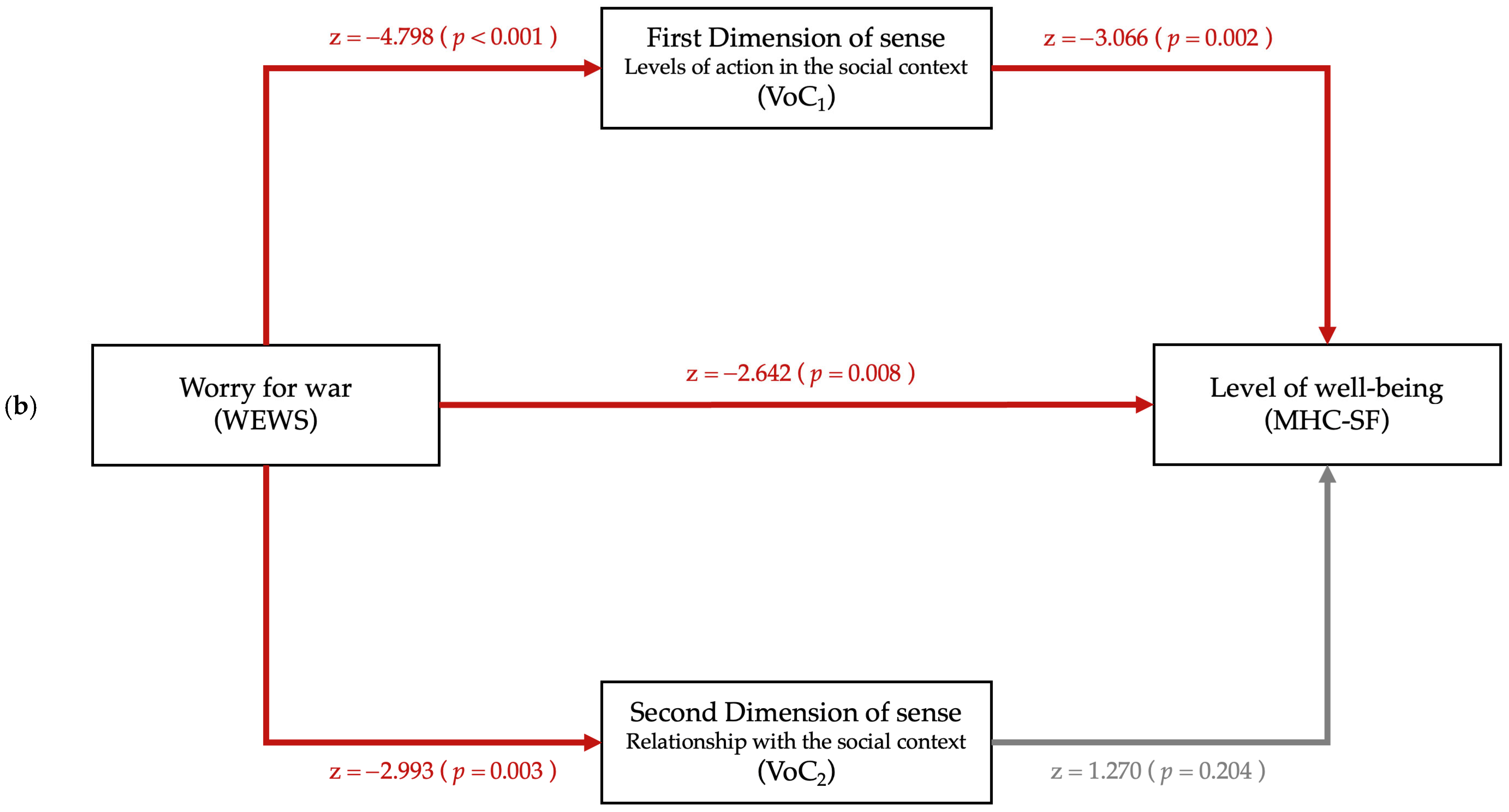

- Finally, mediation models were computed to assess (Q5) how meanings (i.e., Latent Dimensions of Meanings by Views of Context [VoC]) mediate the relations between worry about climate change and war, and levels of wellbeing and general distress.

3. Results

3.1. Detection of Cultural Meanings

3.2. Cluster of Meanings and Cross-Cultural Differences (Q1)

3.3. Determinants of Wellbeing and Distress (Q2, Q3 and Q4)

3.4. Mediational Role of Cultural Meanings (Q5)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Participants and Recruitment

| Demographic Characteristics | N (%) | χ2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Armenia | ||||

| 271 (57.3) | 202 (42.7) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 77 (16.3) | 51 (10.8) | 0.588 | 0.443 |

| Female | 194 (41.0) | 151 (31.9) | |||

| Educational status | Elementary | 35 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 124.052 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 144 (30.4) | 43 (9.1) | |||

| High | 7 (1.5) | 25 (5.3) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 70 (14.8) | 133 (28.1) | |||

| Master | 15 (3.2) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Social status | Single | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 21.002 | <0.001 |

| Married | 257 (54.3) | 166 (35.1) | |||

| Divorced | 14 (3.0) | 32 (6.8) | |||

| Widower | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | |||

Appendix A.2. Measures

Appendix A.3. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

Appendix A.4. Dimension of Meanings

Appendix A.4.1. First Dimension (VoC1)

| Test Value a | Item | Modality of Response |

|---|---|---|

| Commitment to oneself and others (VoC1NEG) | ||

| −13.87 | Taking care of your health | Very important |

| −12.40 | Investing in your future | Very important |

| −11.52 | Thinking about your own happiness | Very important |

| −11.36 | Taking care of the environment | Very important |

| −11.09 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly agree |

| −10.77 | Studying | Very important |

| −10.75 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly agree |

| −10.15 | Respect the rules | Very important |

| −9.77 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Very important |

| −9.76 | Climate change is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly agree |

| −9.67 | Staying with family | Very important |

| −9.59 | Climate change is caused by lack of education | Strongly agree |

| −9.03 | Climate change is caused by insufficient regulations | Strongly agree |

| −8.99 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Very important |

| −8.93 | I feel called to take care of myself | A lot |

| −8.71 | War is caused by lack of education | Strongly agree |

| −8.40 | I feel called to take care of my family | A lot |

| −8.39 | Scholars are reliable | A lot |

| −6.75 | I think I am responsible for my future | A lot |

| −6.65 | Newspaper and TV are reliable | Quite |

| −6.16 | I feel like I belong to the world | A lot |

| −5.68 | I feel called to take care of the community | A lot |

| General disengagement (VoC1POS) | ||

| 12.56 | Respect the rules | Not at all important |

| 11.92 | Taking care of the environment | Not at all important |

| 11.61 | Studying | Not at all important |

| 11.40 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Not at all important |

| 11.01 | Thinking about your own happiness | Not at all important |

| 10.76 | Investing in your future | Not at all important |

| 10.69 | Staying with family | Not at all important |

| 10.59 | Taking care of your health | Not at all important |

| 9.91 | Scholars are reliable | Not at all |

| 9.66 | Taking care of the environment | Slightly important |

| 9.21 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Not at all |

| 9.02 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Slightly important |

| 9.00 | Climate change is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly disagree |

| 9.00 | War change is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly disagree |

| 8.97 | Climate change is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly disagree |

| 8.80 | I think I am responsible for my future | Not at all |

| 8.79 | I feel called to take care of myself | Not at all |

| 8.24 | Social media are reliable | Not at all |

| 8.16 | I feel called to take care of my family | Not at all |

| 8.07 | I am satisfied with my health | Not at all |

| 7.84 | Newspaper and TV are reliable | Not at all |

| 7.05 | I feel like I belong to the world | Not at all |

Appendix A.4.2. Second Dimension (VoC2)

| Test Value a | Item | Modality of Response |

|---|---|---|

| Detachment and disillusionment (VoC2NEG) | ||

| −9.15 | War is caused by lack of education | Strongly agree |

| −8.65 | Climate change is caused by lack of education | Strongly agree |

| −8.00 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly agree |

| −7.66 | War is caused by insufficient or inadequate rules | Strongly agree |

| −7.61 | Climate change is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly disagree |

| −7.56 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly agree |

| −7.54 | Climate change is caused by insufficient or inadequate rules | Strongly disagree |

| −7.43 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Not at all important |

| −7.40 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Not at all important |

| −7.40 | I think my living conditions will improve in the next few years | Strongly disagree |

| −7.19 | I feel called to take care of myself | Not at all |

| −7.14 | Taking care of the environment | Very important |

| −7.11 | Climate change is caused by lack of education | Strongly disagree |

| −7.05 | Studying | Not at all important |

| −6.97 | Investing in your future | Not at all important |

| −6.95 | I feel like I belong to my nation | Not at all |

| −6.85 | Investing in your future | Very important |

| −6.83 | I feel called to take care of my family | Not at all |

| −6.54 | Respect the rules | Very important |

| −6.49 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly disagree |

| −6.49 | Thinking about your own happiness | Very important |

| −6.48 | Politicians are reliable | Not at all |

| Impotence and loneliness (VoC2POS) | ||

| 10.37 | Climate change is caused by lack of education | Moderately agree |

| 10.05 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Moderately agree |

| 9.41 | War is caused by lack of education | Moderately agree |

| 9.15 | Taking care of your health | Moderately important |

| 8.78 | Taking care of the environment | Moderately important |

| 8.77 | Studying | Moderately important |

| 8.56 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Moderately agree |

| 8.49 | Climate change is caused by people’s mentality | Moderately agree |

| 8.43 | Climate change is caused by people’s selfishness | Moderately agree |

| 8.39 | Thinking about your own happiness | Moderately important |

| 7.82 | Investing in your future | Moderately important |

| 7.75 | War is caused by insufficient or inadequate rules | Moderately agree |

| 7.59 | Respect the rules | Moderately important |

| 7.49 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Moderately important |

| 7.36 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Moderately important |

| 7.06 | I think I am responsible for my future | Moderately |

| 6.91 | War is caused by divine will | Moderately agree |

| 6.25 | Climate change is caused by insufficient or inadequate rules | Moderately agree |

| 5.87 | Climate change is caused by divine will | Moderately agree |

| 5.44 | I feel called to take care of myself | Moderately |

| 5.35 | People are not capable of change | A little |

| 5.09 | In life people can only rely on themselves | Moderately |

Appendix A.4.3. Cluster of Meanings

Orientation Towards Self-Care (CL1)

| Test Value a | Item | Modality of Response |

|---|---|---|

| 10.54 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Moderately agree |

| 9.80 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Moderately agree |

| 9.32 | Taking care of your health | Moderately important |

| 8.70 | Climate change is caused by lack of education | Moderately agree |

| 8.56 | Studying | Moderately important |

| 8.49 | Climate change is caused by people’s mentality | Moderately agree |

| 8.31 | Taking care of the environment | Moderately important |

| 8.04 | Investing in your future | Moderately important |

| 7.82 | Respect le rules | Moderately important |

| 7.43 | War is caused by lack of education | Moderately agree |

| 7.30 | Thinking about your own happiness | Moderately important |

| 6.99 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Moderately important |

| 6.51 | Climate change is caused by people’s selfishness | Moderately agree |

| 5.69 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Moderately important |

| 5.63 | Climate change is caused by insufficient regulations | Moderately agree |

| 5.38 | Climate change is caused by divine will | Moderately agree |

| 4.99 | Staying with family | Moderately important |

| 4.71 | War is caused by divine will | Moderately agree |

| 4.51 | I think I am responsible for my future | Moderately |

| 4.49 | Climate change is caused by insufficient regulations | Moderately disagree |

Social and Personal Commitment (CL2)

| Test Value a | Item | Modality of Response |

|---|---|---|

| 13.11 | Climate change is caused by lack of education | Strongly agree |

| 13.09 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly agree |

| 12.60 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly agree |

| 11.80 | Taking care of your health | Very important |

| 11.64 | Climate change is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly agree |

| 11.61 | War is caused by lack of education | Strongly agree |

| 11.03 | Taking care of the environment | Very important |

| 10.84 | Investing in your future | Very important |

| 10.56 | Studying | Very important |

| 10.49 | Climate change is caused by insufficient regulations | Strongly agree |

| 10.46 | Climate change is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly agree |

| 10.01 | Respect the rules | Very important |

| 9.63 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Very important |

| 9.29 | War is caused by insufficient regulations | Strongly agree |

| 9.28 | Thinking about your own happiness | Very important |

| 9.27 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Very important |

| 7.84 | Scholars are reliable | A lot |

| 7.82 | Staying with family | Very important |

| 6.78 | I think I am responsible for my future | A lot |

| 6.40 | I feel called to take care of myself | A lot |

Absolute Devaluation and Social Detachment (CL3)

| Test Value a | Item | Modality of Response |

|---|---|---|

| 9.39 | Respect the rules | Not at all important |

| 8.33 | Taking care of your health | Slightly important |

| 7.75 | Studying | Not at all important |

| 7.29 | Studying | Slightly important |

| 7.29 | Taking care of the environment | Not at all important |

| 7.21 | Taking care of the environment | Slightly important |

| 7.11 | Worry about things that happen in the world | Not at all important |

| 6.88 | Thinking about your own happiness | Not at all important |

| 6.80 | Staying with family | Not at all important |

| 6.67 | Investing in your future | Not at all important |

| 6.45 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Not at all important |

| 6.40 | Scholars are reliable | Not at all |

| 6.40 | Thinking about your own happiness | Slightly important |

| 6.37 | Investing in your future | Slightly important |

| 6.27 | Taking care of your health | Not at all important |

| 6.17 | Respecting the ideologies of others | Slightly important |

| 5.69 | War is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly disagree |

| 5.59 | Climate change is caused by people’s selfishness | Strongly disagree |

| 5.56 | War is caused by people’s mentality | Strongly disagree |

| 5.24 | Social media are reliable | Not at all |

Appendix A.5. Supplementary Tables for the Mediational Role of the Cultural Meanings

| Item | Never/Rarely (%) | Sometimes (%) | Often/Always (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Armenia | Italy | Overall | Armenia | Italy | Overall | Armenia | Italy | |

| 1. I worry about climate change more than other people | 52.9 | 63.3 | 45.0 | 29.4 | 23.8 | 33.6 | 17.8 | 12.9 | 21.4 |

| 2. Thoughts about climate change make me worry about what the future might hold | 45.8 | 62.9 | 33.2 | 30.4 | 25.7 | 33.9 | 23.7 | 11.4 | 32.8 |

| 3. I tend to look for information about climate change in the media | 60.3 | 70.3 | 52.8 | 22.6 | 16.3 | 27.3 | 17.1 | 13.4 | 19.9 |

| 4. I tend to get worried when I hear about climate change, even when the effects of climate change may be far away | 55.0 | 68.8 | 44.7 | 22.6 | 21.3 | 23.6 | 22.4 | 9.9 | 31.7 |

| 5. I believe that the increase in severe weather events may be the result of climate change | 44.8 | 66.3 | 28.8 | 17.5 | 15.3 | 19.2 | 37.6 | 18.3 | 52.0 |

| 6. I care so much about climate change that I feel paralyzed from being able to do anything about it | 71.3 | 65.8 | 75.3 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 17.7 | 10.2 | 14.3 | 7.0 |

| 7. I fear I will not be able to cope with climate change | 61.6 | 79.2 | 48.3 | 19.0 | 13.4 | 23.2 | 19.4 | 7.5 | 28.4 |

| 8. I realized that I was worried about climate change | 54.4 | 68.8 | 43.5 | 23.7 | 20.3 | 26.2 | 22.0 | 10.9 | 30.3 |

| 9. When I start worrying about climate change, I find it hard to stop | 76.3 | 85.2 | 69.7 | 15.6 | 10.9 | 19.2 | 8.1 | 4.0 | 11.1 |

| 10. I worry about how the effects of climate change may affect the lives of people I care about | 48.4 | 60.4 | 39.5 | 25.4 | 21.8 | 28.0 | 26.2 | 17.9 | 32.5 |

| Item | Never/Rarely (%) | Sometimes (%) | Often/Always (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Armenia | Italy | Overall | Armenia | Italy | Overall | Armenia | Italy | |

| 1. I worry about war more than other people | 32.5 | 24.2 | 38.7 | 36.4 | 37.6 | 35.4 | 31.1 | 38.1 | 25.9 |

| 2. Thoughts about war make me worry about what the future might hold | 18.8 | 11.4 | 24.3 | 30.0 | 23.8 | 34.7 | 51.1 | 64.8 | 40.9 |

| 3. I tend to look for information about war in the media | 35.3 | 33.7 | 36.5 | 27.5 | 22.3 | 31.4 | 37.2 | 44.0 | 32.1 |

| 4. I tend to get worried when I hear about war, even when the effects of war may be far away | 20.9 | 12.4 | 27.3 | 26.0 | 22.8 | 28.4 | 53.1 | 64.8 | 44.2 |

| 5. I believe that the increase in severe discord events may be the result of war | 19.9 | 15.8 | 22.9 | 25.8 | 21.8 | 28.8 | 54.3 | 62.4 | 48.3 |

| 6. I care so much about war that I feel paralyzed from being able to do anything about it | 63.9 | 59.9 | 66.8 | 18.0 | 16.3 | 19.2 | 18.2 | 23.8 | 14.0 |

| 7. I fear I will not be able to cope with war | 35.8 | 32.1 | 38.4 | 27.3 | 24.7 | 29.1 | 37.0 | 43.1 | 32.5 |

| 8. I realized that I was worried about war | 24.7 | 15.8 | 31.3 | 31.1 | 25.2 | 35.4 | 44.1 | 58.9 | 33.2 |

| 9. When I start worrying about war, I find it hard to stop | 56.1 | 45.1 | 64.1 | 23.9 | 27.7 | 21.0 | 20.0 | 27.3 | 14.8 |

| 10. I worry about how the effects of war may affect the lives of people I care about | 22.2 | 7.9 | 32.8 | 22.8 | 18.8 | 25.8 | 55.0 | 73.2 | 41.3 |

| Effect | Esteem | SE | Z | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Direct | CCWS > DASS-21 | 0.156 | 0.117 | 1.331 | 0.183 | −0.074 | 0.386 |

| Indirect | CCWS > VoC1 > DASS-21 | −0.019 | 0.033 | −0.568 | 0.570 | −0.084 | 0.046 |

| CCWS > VoC2 > DASS-21 | −0.004 | 0.010 | −0.399 | 0.690 | −0.023 | 0.015 | |

| Total | CCWS > DASS-21 | 0.133 | 0.113 | 1.180 | 0.238 | −0.088 | 0.355 |

| Effect | Esteem | SE | Z | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Direct | WEWS > DASS-21 | 0.355 | 0.112 | 3.176 | 0.001 | 0.136 | 0.574 |

| Indirect | WEWS > VoC1 > DASS-21 | −0.022 | 0.024 | −0.891 | 0.373 | −0.069 | 0.026 |

| WEWS > VoC2 > DASS-21 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 1.245 | 0.213 | −0.012 | 0.052 | |

| Total | WEWS > DASS-21 | 0.353 | 0.108 | 3.266 | 0.001 | 0.141 | 0.565 |

References

- 2023 Azerbaijani offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh. (2025, September 18). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2023_Azerbaijani_offensive_in_Nagorno-Karabakh (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Abdi, H., & Valentin, D. (2007). Multiple correspondence analysis. In N. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics (pp. 1–13). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P. (1991). War, peace, and “the system”: Three perspectives. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 18(3), 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L. R., Hayward, G. M., McElrath, K., & Scherer, Z. (2023). New data visualization shows more young adults worked from home and lived alone during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/young-adults-work-lifestyle-changed-during-pandemic.html (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchielli, B., Cricenti, C., Gallè, F., Sabella, E. A., Liguori, F., Da Molin, G., Liguori, G., Orsi, G. B., Giannini, A. M., Ferracuti, S., & Napoli, C. (2022). Climate changes, natural resources depletion, COVID-19 pandemic, and Russian-Ukrainian war: What is the impact on habits change and mental health? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R. (2022). Gender and survey participation: An event history analysis of the gender effects of survey participation in a probability-based multi-wave panel study with a sequential mixed-mode design. Methods, Data, Analyses, 16(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzécri, J. P. (1979). Sur le calcul des taux d’inertie dans l’analyse d’un questionnaire, addendum et erratum à [BIN. MULT.] [On the calculation of inertia rates in the analysis of a questionnaire, addendum and erratum to]. Les cahiers de l’analyse des données [Data Analysis Notebooks], 4(3), 377–378. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, J., Meares, K., Wilkinson, A., & Freeston, M. (2011). Toward a definition of intolerance of uncertainty: A review of factor analytical studies of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchflower, D. G. (2025). The global decline in the mental health of the young. The Reporter, 1/2025, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Bryson, A. (2025). The mental health of the young in ex-soviet states (NBER Working Paper Series nr. 33356). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w33356 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Bottesi, G., Ghisi, M., Altoè, G., Conforti, E., Melli, G., & Sica, C. (2015). The Italian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottesi, G., Noventa, S., Freeston, M. H., & Ghisi, M. (2019). Seeking certainty about intolerance of uncertainty: Addressing old and new issues through the intolerance of uncertainty scale-revised. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0211929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzynska, B., & Stolarski, M. (2020). Rethinking the relationships between time perspectives and wellbeing: Four hypothetical models conceptualizing the dynamic interplay between temporal framing and mechanisms boosting mental wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. A. P. J., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., & Lang, F. R. (1996). Future time perspective scale [Unpublished manuscript]. Stanford University. Available online: https://lifespan.stanford.edu/download-the-ftp-scale (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Ciavolino, E., Redd, R., Avdi, E., Falcone, M., Fini, V., Kadianaki, I., Kullasepp, K., Mannarini, T., Matsopoulos, A., Mossi, P., Rochira, A., Santarpia, A., Sammut, G., Valsiner, J., Veltri, G. A., & Salvatore, S. (2017). Views of context. An instrument for the analysis of the cultural milieu. A first validation study. Electronic Journal of Applied Statistical Analysis, 10(2), 599–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLongis, A., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, L., Duncan, E., Sutherland, F., Abernethy, C., & Henry, C. (2008). Time perspective and correlates of wellbeing. Time & Society, 17(1), 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, P. (1985). [Review of Multivariate Descriptive Statistical Analysis: Correspondence Analysis and Related Techniques for Large Matrices., by L. Lebart, A. Morineau, & K. M. Warwick]. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 148(1), 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, V. G., Serobyan, A. K., & Grigoryan, A. K. (2021). Analiz svyazi obraza myshleniya s depressiyey, trevozhnost’yu i stressom u studentov iz Armenii i Rossii [Analysis of the relationship between thinking style and depression, anxiety and stress in students from Armenia and Russia]. In E. A. Sergienko, & N. E. Kharlamenkova (Eds.), Psikhologiya Nauka Budushchego. Materialy IX Mezhdunarodnoy konferentsii molodykh uchenykh «Psikhologiya—Nauka budushchego» 18–19 Noyabrya 2021 goda Moskva [Psychology Science of the Future. Proceedings of the IX International Conference of Young Scientists «Psychology—Science of the Future» November 18–19, 2021, Moscow] (pp. 131–135). Institut psikhologii RAN [Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences]. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- European Public Health Alliance. (2025, May). Building better indicators for mental health and wellbeing. EPHA. Available online: https://epha.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/building-better-indicators-for-mental-health-and-wellbeing-report.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Gianfredi, V., Mazziotta, F., Clerici, G., Astorri, E., Oliani, F., Cappellina, M., Catalini, A., Dell’Osso, B. M., Pregliasco, F. E., Castaldi, S., & Benatti, B. (2024). Climate change perception and mental health. Results from a systematic review of the literature. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(1), 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenacre, M., & Blasius, J. (2006). Multiple correspondence analysis and related methods. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y., Gu, S., Lei, Y., & Li, H. (2020). From uncertainty to anxiety: How uncertainty fuels anxiety in a process mediated by intolerance of uncertainty. Neural Plasticity, 2020(1), 8866386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harutyunyan, H., Mukhaelyan, A., Hertelendy, A. J., Voskanyan, A., Benham, T., Issa, F., Hart, A., & Ciottone, G. R. (2021). The psychosocial impact of compounding humanitarian crises caused by war and COVID-19 informing future disaster response. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36(5), 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innocenti, M., Santarelli, G., Faggi, V., Ciabini, L., Castellini, G., Galassi, F., & Ricca, V. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the climate change worry scale. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat—Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (2024). Bes 2023. Il benessere equo e sostenibile in Italia [Bes 2023. Fair and sustainable wellbeing in Italy]. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Available online: https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Bes-2023-Ebook.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Kazaryan, A. M., Edwin, B., Darzi, A., Tamamyan, G. N., Sahakyan, M. A., Aghayan, D. L., Fretland, Å. A., Yaqub, S., & Gayet, B. (2021). War in the time of COVID-19: Humanitarian catastrophe in Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. The Lancet Global Health, 9(3), e243–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2018). Overview of the mental health continuum short form (MHC-SF). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322552717_Overview_of_The_Mental_Health_Continuum_Short_Form_MHC-SF?channel=doi&linkId=5a5f7b68a6fdcc21f48576b2&showFulltext=true (accessed on 25 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D. T. A. M., Kanfer, R., Betts, M., & Rudolph, C. W. (2018). Future time perspective: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103, 867–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koummati, M., Vrublevska, J., De Hert, M., Young, A. H., Fusar-Poli, P., Tandon, R., Javed, A., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2025). Attenuated mental symptoms in the general population: First data from the observational cross-sectional ATTENTION study in Greece. CNS Spectrums, 30(1), e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, C., & Pihkala, P. (2022). Eco-anxiety: What it is and why it matters. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 981814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznar, A. B. (2025). Understanding war: The sociological perspective revisited. European Journal of Social Theory, 28(2), 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, J., & Cantillon, P. (2014). Uncertainty and ambiguity and their association with psychological distress in medical students. Academic Psychiatry, 38(3), 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, F. R., & Carstensen, L. L. (2002). Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychology and Aging, 17, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S. S. S., Fong, J. W. L., van Rijsbergen, N., McGuire, L., Ho, C. C. Y., Cheng, M. C. H., & Tse, D. (2024). Emotional responses and psychological health among young people amid climate change, Fukushima’s radioactive water release, and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, and the mediating roles of media exposure and nature connectedness: A cross-national analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health, 8(6), e365–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebart, L., Morineau, A., & Warwick, K. (1984). Multivariate descriptive statistical analysis. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., Lee, E. H., & Moon, S. H. (2019). Systematic review of the measurement properties of the depression anxiety stress scales–21 by applying updated COSMIN methodology. Quality of Life Research, 28(9), 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Y., & Yen, C. F. (2024). A newly developed scale for assessing individuals’ perceived threat of potential war. Taiwanese Journal of Psychiatry, 38(2), 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C. H., & Davison, A. (2019). Not ‘getting on the bandwagon’: When climate change is a matter of unconcern. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2(1), 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T., & Fedi, A. (2009). Multiple senses of community: The experience and meaning of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(2), 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markosian, C., Khachadourian, V., & Kennedy, C. A. (2021). Frozen conflict in the midst of a global pandemic: Potential impact on mental health in Armenian border communities. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(3), 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, S. E., Hammond, M. D., Sibley, C. G., & Milfont, T. L. (2021). Longitudinal relations between climate change concern and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 78, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. (1981). On social representations. In J. Forgas (Ed.), Social Cognition: Perspectives on everyday understanding (pp. 181–210). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mossi, P., & Salvatore, S. (2011). Psychological transition from meaning to sense. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 4(2), 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Movsisyan, A. S., Galoustian, N., Aydinian, T., Simoni, A., & Aintablian, H. (2022). The immediate mental health effects of the 2020 Artsakh War on Armenians: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Psychiatry Research, 5(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartova-Bochaver, S. K., Donat, M., Kiral Ucar, G., Korneev, A. A., Heidmets, M. E., Kamble, S., Khachatryan, N., Kryazh, I. V., Larionow, P., Rodríguez-González, D., Serobyan, A., Zhou, C., & Clayton, S. (2022). The role of environmental identity and individualism/collectivism in predicting climate change denial: Evidence from nine countries. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 84, 101899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitz, D., Kersjes, C., Thom, J., Hoelling, H., & Mauz, E. (2021). Indicators for public mental health: A scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 714497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, G., Capone, V., Caso, D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2015). The Mental Health Continuum–Short Form (MHC–SF) as a measure of wellbeing in the Italian context. Social Indicators Research, 121(1), 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfund, G. N., Ratner, K., Allemand, M., Burrow, A. L., & Hill, P. L. (2022). When the end feels near: Sense of purpose predicts wellbeing as a function of future time perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 26(6), 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilleltensky, I. (2012). Wellness as fairness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, S. R., Thompson, K. L., McKenzie, M., & Rosenbaum, A. (2016). Psychological research in the internet age: The quality of web-based data. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, R. (2009). Loss and climate change: The cost of parallel narratives. Ecopsychology, 1(3), 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, S. (2012). Uncomfortable knowledge: The social construction of ignorance in science and environmental policy discourses. Economy and Society, 41(1), 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G. M., Tiano, G., & De Rosa, B. (2024). How is the fear of war impacting Italian young adults’ mental health? The mediating role of future anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14, 838–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rod, N. H., Davies, M., de Vries, T. R., Kreshpaj, B., Drews, H., Nguyen, T.-L., & Elsenburg, L. K. (2025). Young adulthood: A transitional period with lifelong implications for health and wellbeing. BMC Global and Public Health, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollo, S., & Benedetto, L. (2023). The War Experience Worry Scale: A new instrument for measuring the worries about war [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Messina. Italian.

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, S., Avdi, E., Battaglia, F., Bernal-Marcos, M. J., Buhagiar, L. J., Ciavolino, E., Fini, V., Kadianaki, I., Kullasepp, K., Mannarini, T., Matsopoulos, A., Mossi, P., Rochira, A., Sammut, G., Santarpia, A., Veltri, G. A., & Valmorbida, A. (2019). The cultural milieu and the symbolic universes of European societies. In S. Salvatore, V. Fini, T. Mannarini, J. Valsiner, & G. A. Veltri (Eds.), Symbolic universes in time of (post)crisis. The future of european societies (pp. 53–133). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samokhvalova, A. G., Tikhomirova, Y. V., Vishnevskaya, O. N., Shipova, N. S., & Asriyan, E. V. (2022). Osobennosti psikhologicheskogo blagopoluchiya russkikh i armyanskikh studentov [Features of the psychological wellbeing of Russian and Armenian students]. Sotsial’naya psikhologiya i obshchestvo [Social Psychology and Society], 13(2), 123–143. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharbert, J., Humberg, S., Kroencke, L., Reiter, T., Sakel, S., ter Horst, J., Utesch, K., Gosling, S. D., Harari, G., Matz, S. C., Schoedel, R., Stachl, C., Aguilar, N. M. A., Amante, D., Aquino, S. D., Bastias, F., Bornamanesh, A., Bracegirdle, C., Campos, L. A. M., … Back, M. D. (2024). Psychological wellbeing in Europe after the outbreak of war in Ukraine. Nature Communications, 15, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, K., & Gow, K. (2010). Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 2(4), 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. E. (2021). Psychometric properties of the climate change worry scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2018). Putting time in a wider perspective: The past, the present, and the future of time perspective theory. The SAGE handbook of personality and individual differences. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02419830/document (accessed on 1 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M., & Matthews, G. (2016). Time perspectives predict mood states and satisfaction with life over and above personality. Current Psychology, 35, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şentürk, S., & Bakır, N. (2021). The relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and the depression, anxiety and stress levels of nursing students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Kıbrıs Türk Psikiyatri ve Psikoloji Dergisi, 3(2), 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In J. T. Jost, & J. Sidanius (Eds.), Political psychology: Key readings (pp. 276–293). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temte, J. L., Holzhauer, J. R., & Kushner, K. P. (2019). Correlation between climate change and dysphoria in primary care. WMJ, 118(2), 71–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Türk, V. (2024, September 9). Human Rights are our mainstay against unbridled power [Opening speech at the 57th session of the Human Rights Council]. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements-and-speeches/2024/09/human-rights-are-our-mainstay-against-unbridled-power (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Twenge, J., & Blanchflower, D. G. (2025). Declining life satisfaction and happiness among young adults in six English-speaking countries. (NBER Working Paper Series nr. 33490). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w33490 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Urbanc, K. (1998, October 11). Perception of the future—From the perspective of adolescents with war experiences. European Integration and Living Conditions of Youth Conference, Koblenz, Germany. Available online: https://www.croris.hr/crosbi/publikacija/prilog-skup/469864?lang=en (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Venuleo, C., Calogiuri, S., & Rollo, S. (2015b). Unplanned reaction or something else? The role of subjective cultures in hazardous and harmful drinking. Social Science & Medicine, 139, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, C., Mossi, P., & Rollo, S. (2019). The social-cultural context of risk evaluation. An exploration of the interplay between cultural models of the social environment and parental control on the risk evaluation expressed by a sample of adolescents. Psicologia della Salute, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, C., Rollo, S., Ferrante, L., Marino, C., & Schimmenti, A. (2022). Being online in the time of COVID-19: Narratives from a sample of young adults and the relationship with wellbeing. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, C., Rollo, S., Marinaci, T., & Calogiuri, S. (2016). Towards a cultural understanding of addictive behaviours. The image of the social environment among problem gamblers, drinkers, internet users and smokers. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(4), 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, C., Salvatore, S., & Mossi, P. (2015a). The role of cultural factors in differentiating pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermishyan, H., Balasanyan, S., & Darbinyan, T. (2023). Youth study Armenia: (In)dependence generation. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung South Caucasus. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/armenien/20652.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Walton, J. R., Nuttall, R. L., & Nuttall, E. V. (1997). The impact of war on the mental health of children: A Salvadoran study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(8), 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamsler, C., Osberg, G., Panagiotou, A., Smith, B., Stanbridge, P., Osika, W., & Mundaca, L. (2023). Meaning-making in a context of climate change: Supporting agency and political engagement. Climate Policy, 23(7), 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 17, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report. Transforming mental health for all. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338 (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Xu, J., Ironside, M. L., Broos, H. C., Johnson, S. L., & Timpano, K. R. (2024). Urged to feel certain again: The role of emotion-related impulsivity on the relationships between intolerance of uncertainty and OCD symptom severity. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(2), 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambianchi, M. (2019). Time perspective and eudaimonic wellbeing in Italian emerging adults. Counseling, 12(3), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambianchi, M., & Ricci Bitti, P. E. (2012). Benessere psicologico e prospettiva temporale negli adolescenti e nei giovani [Psychological wellbeing and time perspective in adolescents and young people]. Psicologia della Salute (Health Psychology), 83–102, Italian. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotareva, A. A. (2020). Sistematicheskiy obzor psikhometricheskikh svoystv shkaly depressii, trevogi i stressa (DASS-21) [Systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)]. Obozrenie psihiatrii i medicinskoj psihologii imeni V.M. Bekhtereva [Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology named after V.M. Bekhterev], 26–37. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J. P., Osin, E. N., Cieciuch, J., Adams, B. G., Ardi, R., Bălţătescu, S., Bogomaz, S., Bhomi, A. L., Clinton, A., de Clunie, G. T., Czarna, A. Z., Esteves, C., Gouveia, V., Halik, M. H. J., Hosseini, A., Khachatryan, N., Kamble, S. V., Kawula, A., … Maltby, J. (2018). The mental health continuum-short form: The structure and application for cross-cultural studies-A 38 nation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1034–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean (SD [SE]) | FCluster (p) | FGroup (p) | FCluster*Group (p) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL1 | CL2 | CL3 | |||||||

| Armenia M (SD) [SE] | Italy M (SD) [SE] | Armenia M (SD) [SE] | Italy M (SD) [SE] | Armenia M (SD) [SE] | Italy M (SD) [SE] | ||||

| MHC-SF | 30.3 (16.3) [4.71] | 36.1 (18.8) [4.44] | 33.1 (10.5) [0.99] | 35.9 (14.3) [1.07] | 31.7 (10.8) [1.22] | 36.1 (15.3) [1.78] | 0.197 (0.821) | 5.327 (0.021) | 0.264 (0.768) |

| DASS-21 | 42.1 (27.0) [7.80] | 41.8 (26.3) [6.20] | 48.5 (29.4) [2.78] | 47.6 (29.6) [2.22] | 41.3 (22.9) [2.60] | 50.1 (30.1) [3.50] | 0.795 (0.452) | 0.395 (0.530) | 1.456 (0.234) |

| IUS-R | 32.4 (9.4) [3.65] | 35.5 (9.2) [3.19] | 34.6 (10.4) [0.99] | 36.8 (9.5) [0.71] | 28.0 (12.6) [1.07] | 29.1 (13.5) [1.07] | 7.284 (<0.001) | 2.348 (0.126) | 0.186 (0.830) |

| FTP | 4.9 (0.7) [0.33] | 4.6 (1.2) [0.24] | 5.1 (0.8) [0.08] | 4.9 (1.0) [0.08] | 4.9 (1.2) [0.07] | 4.1 (1.0) [0.14] | 4.292 (0.014) | 10.780 (0.001) | 0.902 (0.407) |

| CCWS | 18.4 (7.3) [2.83] | 25.1 (9.0) [2.18] | 21.6 (8.4) [0.79] | 26.9 (9.7) [0.73] | 19.1 (9.8) [0.83] | 19.6 (9.2) [1.05] | 6.543 (0.002) | 10.790 (0.001) | 1.532 (0.217) |

| WEWS | 31.1 (7.8) [0.88] | 27.2 (8.4) [0.97] | 36.3 (9.8) [0.92] | 29.8 (8.9) [0.66] | 26.4 (11.0) [0.88] | 20.4 (8.6) [0.97] | 21.036 (<0.001) | 18.791 (<0.001) | 1.055 (0.349) |

| (a) Cluster of Meanings | Frequency of Continuum of Wellbeing from MHC (%) | Total n (%) | χ2 (df) | p | ||

| Flourishing n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Languishing n (%) | ||||

| CL1 | 26 (5.5) | 103 (21.8) | 23 (4.9) | 152 (32.1) | 12.024 (4) | 0.017 |

| CL2 | 51 (10.8) | 195 (41.2) | 45 (9.5) | 291 (61.5) | ||

| Cl3 | 9 (1.9) | 11 (2.3) | 10 (2.1) | 30 (6.3) | ||

| Total | 86 (18.2) | 309 (65.3) | 78 (16.5) | 473 (100.0) | ||

| (b) Nationality | Flourishing n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Languishing n (%) | Total n (%) | χ2 (df) | p |

| Armenia | 31 (6.6) | 135 (28.5) | 36 (7.6) | 202 (42.7) | 2.060 (2) | 0.357 |

| Italy | 55 (11.6) | 174 (36.8) | 42 (8.9) | 271 (57.3) | ||

| Total | 86 (18.2) | 309 (65.3) | 78 (16.5) | 473 (100) | ||

| Predictors | Esteem | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUS-R | −0.236 | 0.0598 | −3.94 | <0.001 |

| FTP | 4706 | 0.6363 | 7.40 | <0.001 |

| CCWS | 0.112 | 0.0665 | 1.69 | 0.093 |

| WEWS | −0.194 | 0.0638 | −3.04 | 0.003 |

| VoC1 | −3.484 | 13.364 | −2.61 | 0.009 |

| VoC2 | 1.700 | 14.668 | 1.16 | 0.247 |

| Predictors | Esteem | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUS-R | 13.072 | 0.111 | 11.727 | <0.001 |

| FTP | −76.063 | 1.186 | −6.415 | <0.001 |

| CCWS | 0.0403 | 0.124 | 0.325 | 0.746 |

| WEWS | 0.3421 | 0.119 | 2.876 | 0.004 |

| VoC1 | 23.631 | 2.490 | 0.949 | 0.343 |

| VoC2 | −37.617 | 2.733 | −1.376 | 0.169 |

| Effect | Esteem | SE | Z | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Direct | CCWS > MHC-SF | 0.046 | 0.063 | 0.737 | 0.461 | −0.077 | 0.170 |

| Indirect | CCWS > VoC1 > MHC-SF | 0.039 | 0.019 | 2.094 | 0.036 | 0.003 | 0.076 |

| CCWS > VoC2 > MHC-SF | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.397 | 0.692 | −0.007 | 0.011 | |

| Total | CCWS > MHC-SF | 0.088 | 0.061 | 1.437 | 0.151 | −0.032 | 0.207 |

| Path coefficients | CCWS > VoC1 | −0.013 | 0.002 | −6.372 | <0.001 | −0.017 | −0.009 |

| CCWS > VoC2 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.409 | 0.683 | −0.003 | 0.005 | |

| VoC1 > MHC-SF | −2.943 | 1.328 | −2.217 | 0.027 | −5.545 | −0.341 | |

| VoC2 > MHC-SF | 2.406 | 1.452 | 1.657 | 0.097 | −0.439 | 5.251 | |

| IUS-R > CCWS | 0.194 | 0.043 | 4.470 | <0.001 | 0.109 | 0.279 | |

| FTP > CCWS | −1.187 | 0.450 | −2.637 | 0.008 | −2.069 | −0.305 | |

| IUS-R > VoC1 | −0.009 | 0.002 | −4.652 | <0.001 | −0.013 | −0.005 | |

| FTP > VoC1 | −0.162 | 0.021 | −7.847 | <0.001 | −0.203 | −0.122 | |

| IUS-R > VoC2 | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.862 | 0.388 | −0.005 | 0.002 | |

| FTP > VoC2 | −0.038 | 0.019 | −2.011 | 0.044 | −0.075 | 0.000 | |

| IUS > MHC-SF | −0.254 | 0.060 | −4.262 | <0.001 | −0.371 | −0.137 | |

| FTP > MHC-SF | 4.639 | 0.637 | 7.278 | <0.001 | 3.390 | 5.888 | |

| Effect | Esteem | SE | Z | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Direct | WEWS > MHC-SF | −0.159 | 0.060 | −2.642 | 0.008 | −0.277 | −0.041 |

| Indirect | WEWS > VoC1 > MHC-SF | 0.039 | 0.015 | 2.583 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.069 |

| WEWS > VoC2 > MHC-SF | −0.010 | 0.009 | −1.169 | 0.242 | −0.027 | 0.007 | |

| Total | WEWS > MHC-SF | −0.130 | 0.059 | −2.206 | 0.027 | −0.245 | −0.014 |

| Path coefficients | WEWS > VoC1 | −0.010 | 0.002 | −4.798 | <0.001 | −0.014 | −0.006 |

| WEWS > VoC2 | −0.005 | 0.002 | −2.993 | 0.003 | −0.009 | −0.002 | |

| VOC1 > MHC-SF | −3.979 | 1.298 | −3.066 | 0.002 | −6.523 | −1.435 | |

| VoC2 > MHC-SF | 1.851 | 1.458 | 1.270 | 0.204 | −1.006 | 4.708 | |

| IUS-R > WEWS | 0.201 | 0.045 | 4.468 | <0.001 | 0.113 | 0.289 | |

| FTP > WEWS | 0.493 | 0.466 | 1.059 | 0.290 | −0.420 | 1.407 | |

| IUS-R > VoC1 | −0.010 | 0.002 | −4.867 | <0.001 | -0.014 | −0.006 | |

| FTP > VoC1 | −0.142 | 0.021 | −6.767 | <0.001 | -0.183 | −0.101 | |

| IUS-R > VoC2 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.185 | 0.853 | −0.004 | 0.003 | |

| FTP > VoC2 | −0.036 | 0.019 | −1.947 | 0.052 | −0.073 | 0.000 | |

| IUS-R > MHC-SF | −0.227 | 0.059 | −3.819 | <0.001 | -0.343 | −0.110 | |

| FTP > MHC-SH | 4.489 | 0.620 | 7.235 | <0.001 | 3.273 | 5.705 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ingrassia, M.; Khachatryan, N.; Rollo, S.; Arakelyan, E.; Mikayelyan, T.; Benedetto, L. Youths’ Wellbeing Between Future and Uncertainty Across Cultural Contexts: A Focus on Latent Meanings as Mediational Factors. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120244

Ingrassia M, Khachatryan N, Rollo S, Arakelyan E, Mikayelyan T, Benedetto L. Youths’ Wellbeing Between Future and Uncertainty Across Cultural Contexts: A Focus on Latent Meanings as Mediational Factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(12):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120244

Chicago/Turabian StyleIngrassia, Massimo, Narine Khachatryan, Simone Rollo, Edita Arakelyan, Tsaghik Mikayelyan, and Loredana Benedetto. 2025. "Youths’ Wellbeing Between Future and Uncertainty Across Cultural Contexts: A Focus on Latent Meanings as Mediational Factors" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 12: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120244

APA StyleIngrassia, M., Khachatryan, N., Rollo, S., Arakelyan, E., Mikayelyan, T., & Benedetto, L. (2025). Youths’ Wellbeing Between Future and Uncertainty Across Cultural Contexts: A Focus on Latent Meanings as Mediational Factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(12), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15120244