Future Time Perspective and Locomotion Jointly Predict Anticipatory Pleasure in Adolescence: An Integrative Hierarchical Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

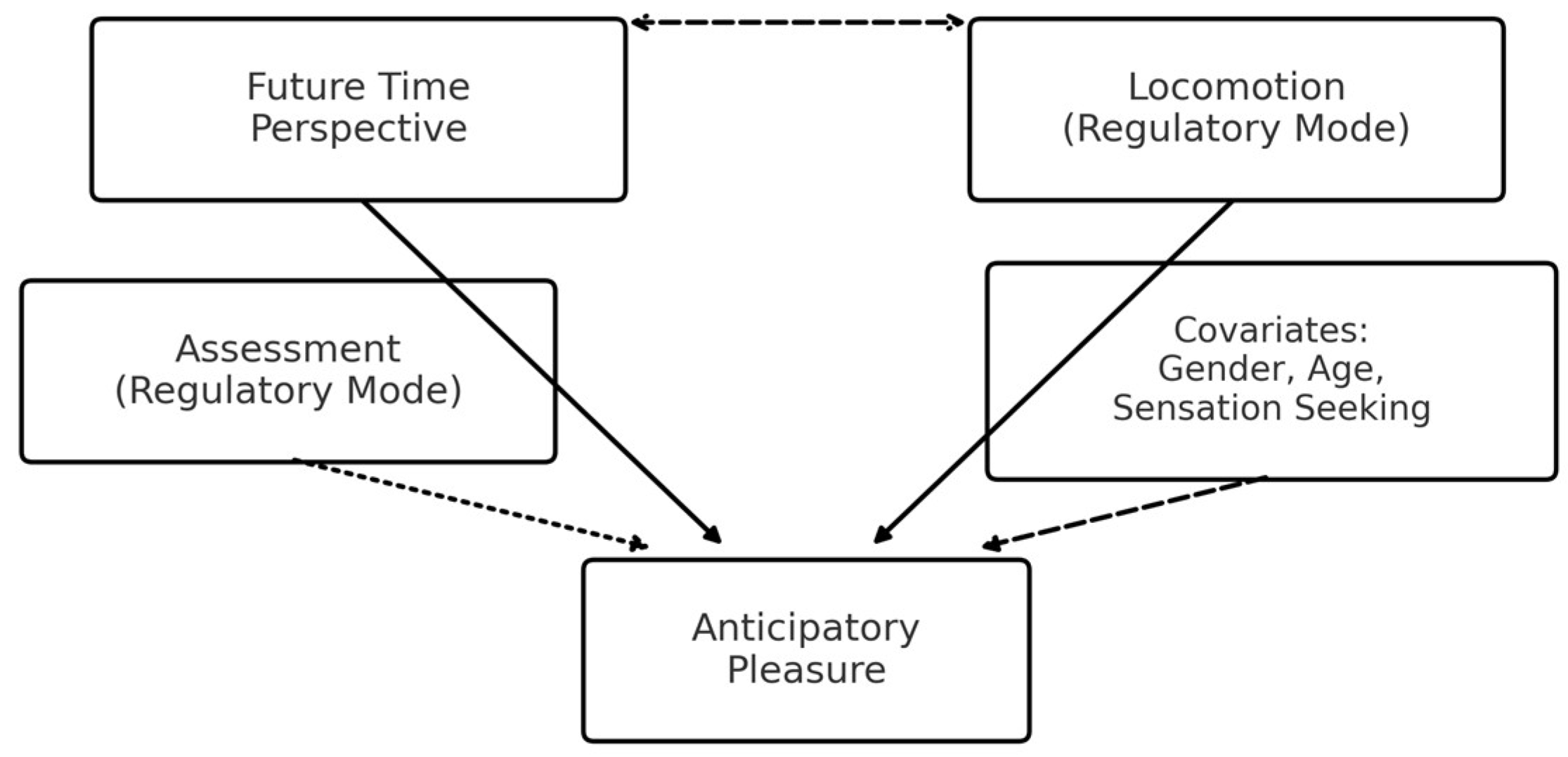

1.1. Gap and Contribution

1.2. Integrative Theoretical Model

1.3. Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

- The Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI), originally developed by Zimbardo and Boyd (2014) and validated in Italian by D’Alessio et al. (2003), is a widely used self-report questionnaire designed to measure individuals’ attitudes toward time across five distinct dimensions. Each of these dimensions reflects a unique temporal orientation, shaping how individuals perceive and respond to their past, present, and future. The ZTPI is particularly relevant for assessing how time perspective influences decision-making, goal setting, and motivational tendencies, which are critical during adolescence. Participants respond to 56 items, indicating their level of agreement or disagreement on a Likert scale (ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”). This format allows participants to express the extent to which each time orientation resonates with their personal views and behaviors. The ZTPI measures five specific time perspectives, capturing a broad range of temporal attitudes: (1) Past-Negative. This dimension assesses the tendency to focus on negative past experiences, such as failures, regrets, and trauma. Individuals scoring high in this area often view their past with disappointment or resentment, which can affect their outlook on the present and future. (2) Past-Positive. This dimension reflects a nostalgic, positive orientation towards past experiences. Those with a high Past-Positive score remember the past fondly and draw strength from positive memories, which can foster a stable sense of identity and security. (3) Present-Hedonistic. This scale measures a present-focused, pleasure-oriented perspective. Individuals high in Present-Hedonistic tend to prioritize immediate gratification, seek stimulating experiences, and often engage in spontaneous or risk-taking behaviors, sometimes disregarding future consequences. (4) Present-Fatalistic captures a belief that life events are governed by fate or chance, leading to a sense of powerlessness over personal outcomes. High scores on this scale are often associated with a passive or resigned attitude toward both present circumstances and future planning. (5) The Future dimension evaluates an individual’s orientation towards future goals, aspirations, and the importance of delayed gratification. High scores indicate a focus on long-term planning and the belief that present actions are instrumental in achieving future success and rewards. The ZTPI has shown moderate to strong internal reliability across its five dimensions, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.60 to 0.72, indicating moderate reliability for this scale within the sample.

- The Regulatory Mode Scale (RMS), originally developed by Kruglanski et al. (2018) and validated in Italian by Pierro et al. (2006), is a psychometric tool designed to assess individuals’ self-regulatory tendencies, specifically capturing two distinct regulatory modes: Assessment and Locomotion. These regulatory modes represent different approaches to self-regulation, influencing how individuals pursue goals, make decisions, and engage in daily activities. The RMS is especially relevant in studying adolescent behavior as it provides insights into the processes underlying goal-setting, decision-making, and action-taking, all of which are key aspects of development during this life stage. The RMS consists of 24 items, split evenly between the two subscales (12 items for Assessment and 12 for Locomotion). Each item uses a Likert scale, where participants indicate their level of agreement with statements related to their regulatory style (e.g., “I often critique myself to find areas of improvement” for Assessment; “I am constantly on the move from one activity to another” for Locomotion). This format allows respondents to express their regulatory preferences in various situations, capturing the balance between critical reflection and action orientation. The RMS evaluates self-regulation through two independent yet complementary dimensions: (1) Assessment. This mode reflects an evaluative, comparative approach to self-regulation, where individuals critically assess their current status and alternative paths. People with a high Assessment orientation tend to carefully consider all options and potential outcomes before taking action, aiming to make the “right” decision. This mode is associated with perfectionism, critical self-reflection, and a desire to meet high standards. Individuals high in Assessment are meticulous and detail-oriented, often seeking to improve their decisions and actions through continuous comparison and evaluation. (2) Locomotion represents a dynamic, action-oriented approach to self-regulation, where the primary focus is on moving forward and progressing towards goals without delay or distraction. Those high in Locomotion are motivated to transition smoothly from one activity to the next, prioritizing efficiency and momentum. This mode is linked to proactive behavior, adaptability, and a strong focus on goal completion. Locomotion-oriented individuals are typically less preoccupied with perfection and comparison, concentrating instead on making steady progress and achieving tangible outcomes. This instrument demonstrated good reliability in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.76.

- The Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS-V), initially developed by Zuckerman (1971) and adapted in Italian by Manna et al. (2013), is a psychometric instrument designed to measure individual differences in sensation-seeking behavior. Sensation seeking is defined as the need for varied, novel, and complex experiences and the willingness to take physical and social risks to achieve such experiences. Given its relevance to adolescence, a period often marked by increased exploration, risk-taking, and identity formation, the SSS-V is particularly suitable for studying sensation-seeking tendencies in this age group. The SSS-V is a self-administered questionnaire comprising 40 items, with 10 items per subscale. Each item is presented as a forced-choice statement, where participants select between two options that best describe their preferences (e.g., “I would like to try bungee jumping” vs. “I would never want to try bungee jumping”). This format captures individual differences in sensation-seeking tendencies across the four dimensions, reflecting both attraction to high-stimulation environments and the propensity to engage in risk-taking behaviors. The SSS-V assesses sensation seeking across four subscales, each targeting a distinct aspect of the sensation-seeking trait: (1) Thrill and Adventure Seeking (TAS) captures the desire for excitement and novelty through physically challenging and often risky activities, such as extreme sports. Individuals with high TAS scores are inclined to seek high-stimulation experiences that involve physical risks and excitement. (2) Experience Seeking (ES) reflects a preference for new sensory or cognitive experiences, often through unconventional or creative activities. High scorers on the ES subscale are likely to engage in exploratory behaviors, including travel, art, and unconventional lifestyles. (3) Disinhibition (DIS) measures a tendency towards impulsivity and a lack of restraint, especially in social situations. Individuals with high DIS scores often pursue social risks, such as substance use or unrestrained social interactions, to satisfy their need for stimulation. (4) Boredom Susceptibility (BS) assesses a low tolerance for monotony and repetitive tasks. Individuals scoring high in boredom susceptibility are easily frustrated by routine and seek constant changes to avoid feeling unstimulated. SSS-V demonstrated in this study good internal reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.60 to 0.80 for the various subscales.

- The Anticipatory Pleasure Scale (APS), originally developed by Gard et al. (2006) and validated in Italian by Stratta et al. (2011), is a self-report instrument designed to measure the capacity for anticipatory pleasure, or the positive emotions associated with looking forward to future events. Anticipatory pleasure is a crucial component of the broader hedonic experience, distinguishing the motivation and excitement for potential future rewards (wanting) from the satisfaction derived from immediate experiences (liking). This distinction is especially relevant during adolescence, a developmental period characterized by goal formation and future planning. The APS consists of 18 items that participants rate on a Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”. Ten items measure anticipatory pleasure, while the remaining eight items assess consummatory pleasure. This format allows participants to express the degree to which they experience excitement for upcoming events versus satisfaction from present or past experiences, providing a nuanced view of their hedonic capacity. The APS evaluates two primary aspects of pleasure, each reflecting a distinct stage in the hedonic process: (1) Anticipatory Pleasure (Wanting) focuses on the motivational aspect of pleasure, capturing an individual’s excitement and enthusiasm for future positive events. High scores on this dimension indicate a strong capacity to derive joy from envisioning future experiences, which can influence goal-setting and future-oriented planning. (2) Consummatory Pleasure (Liking) assesses pleasure derived from immediate or completed experiences, such as the enjoyment felt when a desired goal is achieved. While anticipatory pleasure (wanting) is linked to motivation for future actions, consummatory pleasure (liking) reflects satisfaction in the present moment. In the current sample, internal consistency was α = 0.81 for the anticipatory subscale and α = 0.76 for the consummatory subscale.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Sample Characteristics

3.2. Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity

3.3. Anticipatory Pleasure: Hierarchical Prediction from Regulatory Modes and Time Perspective

3.4. Structural Model (SEM): Mediation and Moderation with Simultaneous Controls

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aghevli, M. A., Blanchard, J. J., & Horan, W. P. (2003). The expression and experience of emotion in schizophrenia: A study of social interactions. Psychiatry Research, 119(3), 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherton, O. E. (2020). Typical and atypical self-regulation in adolescence: The importance of studying change over time. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(1), e12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, H. M., Webb, T. L., Sirois, F. M., & Gibson-Miller, J. (2021). Understanding the effects of time perspective: A meta-analysis testing a self-regulatory framework. Psychological Bulletin, 147(3), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barelli, E., Tasquier, G., Caramaschi, M., Satanassi, S., Fantini, P., Branchetti, L., & Levrini, O. (2022). Making sense of youth futures narratives: Recognition of emerging tensions in students’ imagination of the future. Frontiers in Education, 7, 911052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, R. L., Bailey, M. J., & Polanco, C. I. (2023). How the COVID-19 pandemic shaped adolescents’ future orientations: Insights from a global scoping review. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, M., Guarino, A., De Pascalis, V., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2003). Testing Zimbardo’s Stanford time perspective inventory (STPI)-short form. Time & Society, 12(2–3), 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G., & Lyu, H. (2021). Future expectations and internet addiction among adolescents: The roles of intolerance of uncertainty and perceived social support. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 727106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajkowska, M., Quirin, M., & Rauthmann, J. (2023). Personality dynamics: Regulatory mechanisms and processes. Journal of Personality, 91(4), 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieulaine, N., & Martinez, F. (2010). Time under control: Time perspective and desire for control in substance use. Addictive Behaviors, 35(8), 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieulaine, N., & Martinez, F. (2011). About the fuels of self-regulation: Time perspective and desire for control in adolescents substance use. In The psychology of self-regulation (pp. 102–121). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fomina, T., Burmistrova-Savenkova, A., & Morosanova, V. (2020). Self-regulation and psychological well-being in early adolescence: A two-wave longitudinal study. Behavioral Sciences, 10(3), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, D. E., Gard, M. G., Kring, A. M., & John, O. P. (2006). Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: A scale development study. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1086–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germano, G., & Brenlla, M. E. (2021). Effects of time perspective and self-control on psychological distress: A cross-sectional study in an Argentinian sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, R., Salmon, K., & Low, J. (2022). Retrieval-induced forgetting for autobiographical memories beyond recall rates: A developmental study. Developmental Psychology, 58(2), 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H., Li, X., Shen, X., Jiang, H., Xiao, H., & Lyu, H. (2024). Reciprocal relationships between future time perspective and self-control among adolescents in China: A longitudinal study. Current Psychology, 43(12), 11062–11070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipson, W. E., Coplan, R. J., Dufour, M., Wood, K. R., & Bowker, J. C. (2021). Time alone well spent? A person-centered analysis of adolescents’ solitary activities. Social Development, 30(4), 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairys, A., & Liniauskaite, A. (2015). Time perspective and personality. In Time perspective theory; Review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 99–113). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D. T., Kanfer, R., Betts, M., & Rudolph, C. W. (2018). Future time perspective: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(8), 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, S. C., & Madsen, O. J. (2024). Dissecting the achievement generation: How different groups of early adolescents experience and navigate contemporary achievement demands. Journal of Youth Studies, 27(5), 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A. W., Thompson, E. P., Higgins, E. T., Atash, M. N., Pierro, A., Shah, J. Y., & Spiegel, S. (2018). To “do the right thing” or to “just do it”: Locomotion and assessment as distinct self-regulatory imperatives. In The motivated mind (pp. 299–343). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F., Pallini, S., Baumgartner, E., Guarino, A., & Baiocco, R. (2016). Parent and peer attachment relationships and time perspective in adolescence: Are they related to satisfaction with life? Time & Society, 25(1), 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K., Barry, T. J., Hallford, D. J., Jimeno, M. V., Solano Pinto, N., & Ricarte, J. J. (2022). Autobiographical memory specificity and detailedness and their association with depression in early adolescence. Journal of Cognition and Development, 23(5), 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Razza, R. A., Zhang, Y., & Merrin, G. J. (2024). Differential growth trajectories of behavioral self-regulation from early childhood to adolescence: Implication for youth domain-general and school-specific outcomes. Applied Developmental Science, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Wang, X., Ying, J., Shi, J., & Wu, X. (2023). Emotional involvement matters, too: Associations among parental involvement, time management and academic engagement vary with Youth’s developmental phase. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(4), 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancone, S., Celia, G., Zanon, A., Gentile, A., & Diotaiuti, P. (2025a). Psychosocial profiles and motivations for adolescent engagement in hazardous games: The role of boredom, peer influence, and self-harm tendencies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1527168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancone, S., Corrado, S., Tosti, B., Spica, G., & Diotaiuti, P. (2024a). Integrating digital and interactive approaches in adolescent health literacy: A comprehensive review. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1387874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancone, S., Corrado, S., Tosti, B., Spica, G., Di Siena, F., Misiti, F., & Diotaiuti, P. (2024b). Enhancing nutritional knowledge and self-regulation among adolescents: Efficacy of a multifaceted food literacy intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1405414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancone, S., Zanon, A., Marotta, G., Celia, G., & Diotaiuti, P. (2025b). Temporal perspectives, sensation-seeking, and cognitive distortions as predictors of adolescent gambling behavior: A study in Italian high schools. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1602316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, G., Faraci, P., & Como, M. R. (2013). Factorial structure and psychometric properties of the Sensation Seeking Scale–Form V (SSS-V) in a sample of Italian adolescents. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 9(2), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M. T., Perry, J. L., & Cole, J. C. (2018). Further evidence for the domain specificity of consideration of future consequences in adolescents and university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 128, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, Z. R., Barber, S. J., Vasilenko, S. A., Chandler, J., & Howell, R. (2022). Thinking about the past, present, and future: Time perspective and self-esteem in adolescents, young adults, middle-aged adults, and older adults. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 40(1), 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, Z. R., & Worrell, F. C. (2014). The past, the present, and the future: A conceptual model of time perspective in adolescence. In Time perspective theory; Review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 115–129). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L., Speltini, G., Passini, S., & Carelli, M. G. (2016). Time perspective in adolescents and young adults: Enjoying the present and trusting in a better future. Time & Society, 25(3), 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, M., Wiśniewska, M., & Nęcka, E. (2020). Time perspective and self-control: Metacognitive management of time is important for efficient self-regulation of behavior. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 8(2), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, J. E. (2006). Thinking about and acting upon the future: Development of future orientation across the life span. In Understanding behavior in the context of time (pp. 31–58). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttin, J. (2014). Attitudes towards the personal past, present, and future. In Future Time Perspective and Motivation (pp. 91–99). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, J. H., & Berkman, E. T. (2018). The development of self and identity in adolescence: Neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierro, A., Kruglanski, A. W., & Higgins, E. T. (2006). Regulatory mode and the joys of doing: Effects of ‘locomotion’ and ‘assessment’on intrinsic and extrinsic task-motivation. European Journal of Personality: Published for the European Association of Personality Psychology, 20(5), 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D., Duckworth, A. L., Sznitman, S., & Park, S. (2010). Can adolescents learn self-control? Delay of gratification in the development of control over risk taking. Prevention Science, 11(3), 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Netzer, P., & Shoshani, A. (2020). Authentic inner compass, well-being, and prioritization of positivity and meaning among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, T., & Higata, A. (2016). Sharing the past and future among adolescents and their parents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(3), 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Lacante, M. (2004). Placing motivation and future time perspective theory in a temporal perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 16(2), 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomontos-Kountouri, O., & Hatzittofi, P. (2016). Brief report: Past, present, emergent and future identities of young inmates. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L., Graham, S., O’brien, L., Woolard, J., Cauffman, E., & Banich, M. (2009). Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development, 80(1), 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratta, P., Pacifico, R., Riccardi, I., Daneluzzo, E., & Rossi, A. (2011). Anticipatory and consummatory pleasure: Validation study of the italian version of the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale. Journal of Psychopathology, 17, 322–327. [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani-Aidan, Y., & Melkman, E. (2022). Future orientation among at-risk youth in Israel. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(4), 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M., & McLean, K. C. (2016). Understanding identity integration: Theoretical, methodological, and applied issues. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanrikulu, G., & Mouratidis, A. (2023). Life aspirations, school engagement, social anxiety, social media use and fear of missing out among adolescents. Current Psychology, 42(32), 28689–28699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasa, R. A., Pine, D. S., Thorn, J. M., Nelson, T. E., Spinelli, S., Nelson, E., Maheu, F. S., Ernst, M., Bruck, M., & Mostofsky, S. H. (2011). Enhanced right amygdala activity in adolescents during encoding of positively valenced pictures. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 1(1), 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, J., & Revelle, W. (2023). It’s about time: Emphasizing temporal dynamics in dynamic personality regulation. Journal of Personality, 91(4), 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M., Rudolph, T., Linares Gutierrez, D., & Winkler, I. (2015). Time perspective and emotion regulation as predictors of age-related subjective passage of time. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(12), 16027–16042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G., & Burrow, A. L. (2023). Profiles of personal and ecological assets: Adolescents’ motivation and engagement in self-driven learning. Current Psychology, 42(16), 14025–14037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2014). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. In Time perspective theory; review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 17–55). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M. (1971). Dimensions of sensation seeking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 36(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 535 | 34.7 |

| Female | 1005 | 65.3 | |

| Age bands | 14–15 years | 493 | 32 |

| 16–17 years | 708 | 46 | |

| 18–19 years | 339 | 22 | |

| Parental education (highest in household) | ≤Lower secondary | 308 | 20 |

| Upper secondary | 739 | 48 | |

| Tertiary | 493 | 32 | |

| Parental employment | 0 employed | 216 | 14 |

| ≥1 employed | 1324 | 86 | |

| Family Affluence (FAS-III quartiles) | Q1 (lowest) | 385 | 25 |

| Q2 | 385 | 25 | |

| Q3 | 385 | 25 | |

| Q4 (highest) | 385 | 25 | |

| Migration background | Both parents Italy | 1263 | 82 |

| ≥1 parent abroad | 277 | 18 | |

| Living arrangement | Two-parent | 1201 | 82 |

| Other | 339 | 22 | |

| School track | Lyceum | 847 | 55 |

| Technical-vocational | 693 | 45 | |

| Grade level | I° | 240 | 15.6 |

| II° | 253 | 16.4 | |

| III° | 355 | 23.1 | |

| IV° | 353 | 22.9 | |

| V° | 339 | 22 | |

| Recruitment | High school A (random sampling) | 703 | 45.7 |

| High school B (random sampling) | 652 | 42.3 | |

| Friendship networks (outreach extension) | 185 | 12 |

| Scale | Subscale | Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory | Past-Negative | 3.10 | 0.75 |

| Past-Positive | 3.60 | 0.80 | |

| Present-Hedonistic | 2.85 | 0.70 | |

| Present-Fatalistic | 2.60 | 0.65 | |

| Future | 3.55 | 0.78 | |

| Regulatory Mode Scale | Assessment | 3.20 | 0.75 |

| Locomotion | 3.90 | 0.65 | |

| Sensation Seeking Scale | Thrill and Adventure Seeking | 4.20 | 0.70 |

| Experience Seeking | 3.90 | 0.68 | |

| Disinhibition | 4.00 | 0.72 | |

| Boredom Susceptibility | 3.80 | 0.66 | |

| Anticipatory Pleasure Scale | Anticipatory Pleasure (Wanting) | 4.50 | 0.68 |

| Consummatory Pleasure (Liking) | 4.20 | 0.64 |

| Variable | Gender | Mean (M) | SD | t | p | Hedges’ g (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZTPI: Future | Female | 3.65 | 0.52 | −2.082 | 0.03 | −0.11 (−0.22, −0.01) |

| Male | 3.45 | 0.87 | ||||

| ZTPI: Present-Hedonistic | Male | 2.73 | 0.11 | 2.082 | 0.02 | 0.11 (0.01, 0.22) |

| Female | 2.44 | 0.05 | ||||

| APS: Anticipatory Pleasure | Female | 4.71 | 0.09 | −2.480 | 0.01 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.03) |

| Male | 4.34 | 0.11 | ||||

| SSS-V: Thrill and Adventure Seeking | Male | 4.40 | 0.72 | 2.310 | 0.02 | 0.12 (0.02, +0.23) |

| Female | 3.98 | 0.68 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Past-Negative | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Past-Positive | −0.12 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. Present-Hedonistic | 0.15 ** | −0.10 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. Present-Fatalistic | 0.28 ** | −0.08 * | 0.28 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. Future | −0.25 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.18 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. Assessment | 0.18 ** | 0.05 | −0.12 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.24 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. Locomotion | −0.10 ** | 0.12 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.30 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 8. Thrill and Adventure Seeking | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.35 ** | 0.10 ** | −0.05 | −0.18 ** | −0.16 ** | 1 | |||||

| 9. Experience Seeking | −0.08 * | 0.06 | 0.25 ** | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.21 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.45 ** | 1 | ||||

| 10. Disinhibition | 0.12 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.38 ** | 1 | |||

| 11. Boredom Susceptibility | 0.20 ** | −0.08 * | 0.30 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.08 * | 0.40 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.35 ** | 1 | ||

| 12. Anticipatory Pleasure | −0.05 | 0.18 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.08 * | 0.22 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.08 * | 1 | |

| 13. Consummatory Pleasure | −0.08 * | 0.20 ** | 0.12 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.05 | −0.10 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.40 ** | 1 |

| Block 1: Assessment + Covariates | ||||

| Predictor | β (std.) | SE | T | p |

| Assessment | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.12 | 0.03 |

| Sex (female = 1) | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.06 | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.34 | 0.181 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.411 |

| Block 2: +Locomotion (Primary Predictor) | ||||

| Predictor | β (std.) | SE | T | p |

| Locomotion (primary) | 0.28 | 0.02 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| Assessment | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.22 | 0.222 |

| Sex (female = 1) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.78 | 0.006 |

| Age (years) | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.45 | 0.149 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.362 |

| Block 3: +Future (Secondary Predictor) | ||||

| Predictor | β (std.) | SE | T | p |

| Locomotion (primary) | 0.26 | 0.02 | 10.78 | <0.001 |

| Future (secondary) | 0.11 | 0.02 | 4.65 | <0.001 |

| Assessment | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.311 |

| Sex (female = 1) | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.52 | 0.012 |

| Age (years) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.06 | 0.29 |

| Sensation seeking | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.568 |

| Model | R2 | Adj. R2 | ΔR2 | ΔF | p(Δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Assessment + covariates | 0.07 | 0.07 | - | - | - |

| Block 2: +Locomotion | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 141.8 | <0.001 |

| Block 3: +Future | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 27.9 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mancone, S.; Zanon, A.; Gentile, A.; Marotta, G.; Di Siena, F.; Falese, L.; Diotaiuti, P. Future Time Perspective and Locomotion Jointly Predict Anticipatory Pleasure in Adolescence: An Integrative Hierarchical Model. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110238

Mancone S, Zanon A, Gentile A, Marotta G, Di Siena F, Falese L, Diotaiuti P. Future Time Perspective and Locomotion Jointly Predict Anticipatory Pleasure in Adolescence: An Integrative Hierarchical Model. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(11):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110238

Chicago/Turabian StyleMancone, Stefania, Alessandra Zanon, Adele Gentile, Giulio Marotta, Francesco Di Siena, Lavinia Falese, and Pierluigi Diotaiuti. 2025. "Future Time Perspective and Locomotion Jointly Predict Anticipatory Pleasure in Adolescence: An Integrative Hierarchical Model" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 11: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110238

APA StyleMancone, S., Zanon, A., Gentile, A., Marotta, G., Di Siena, F., Falese, L., & Diotaiuti, P. (2025). Future Time Perspective and Locomotion Jointly Predict Anticipatory Pleasure in Adolescence: An Integrative Hierarchical Model. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(11), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110238