Key Competencies for Adolescent Well-Being: An Intervention Program in Secondary Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

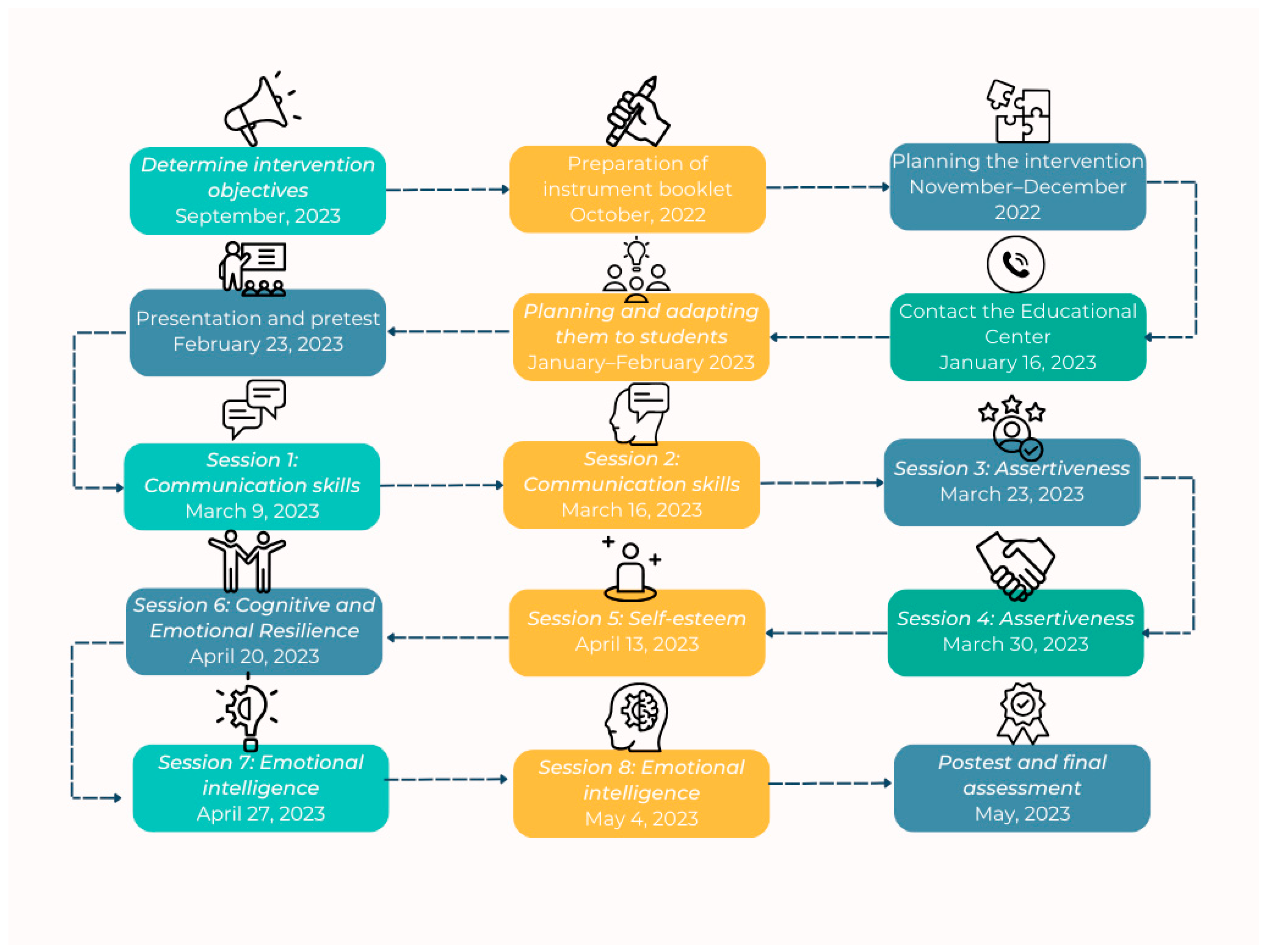

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

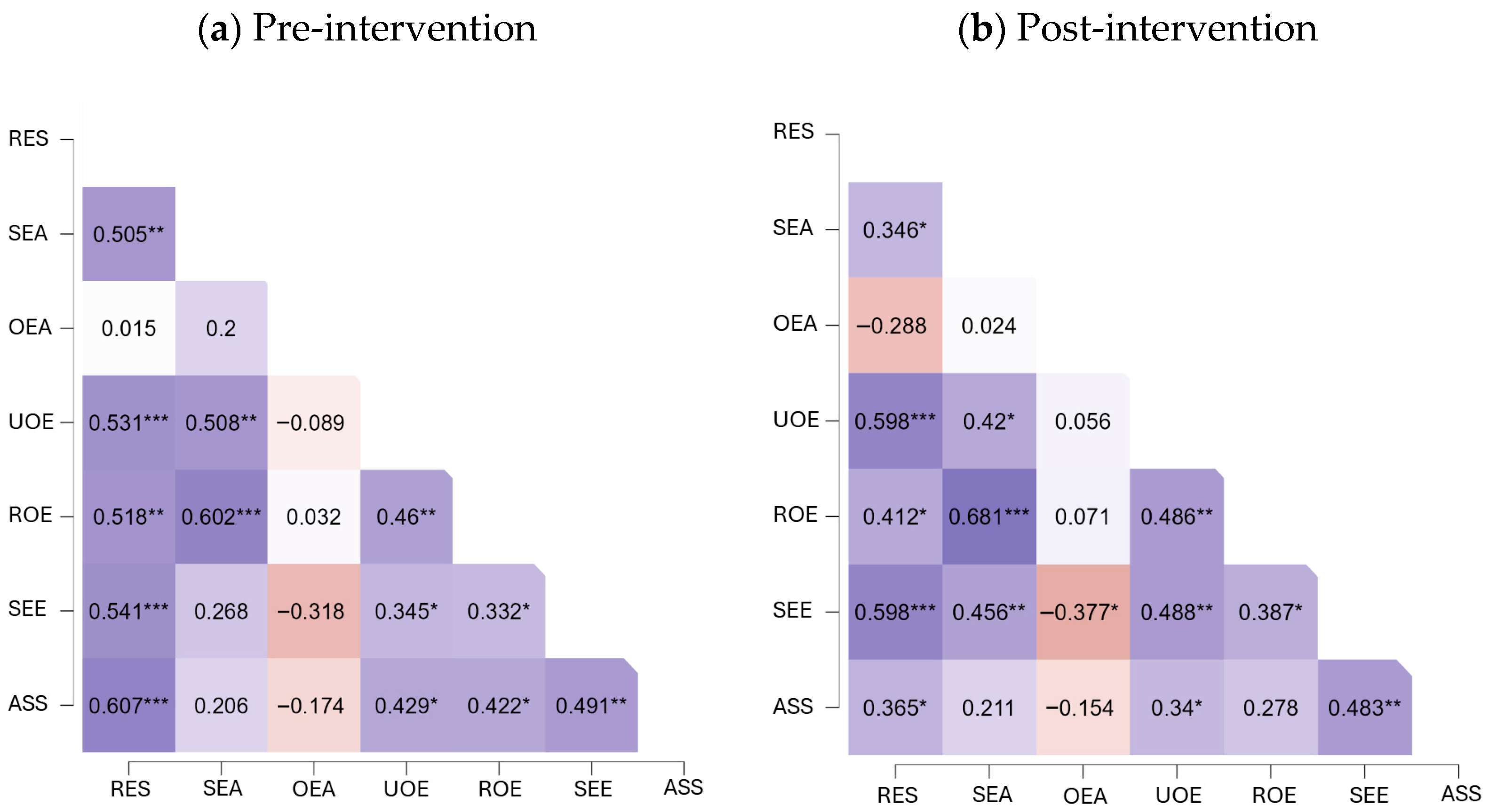

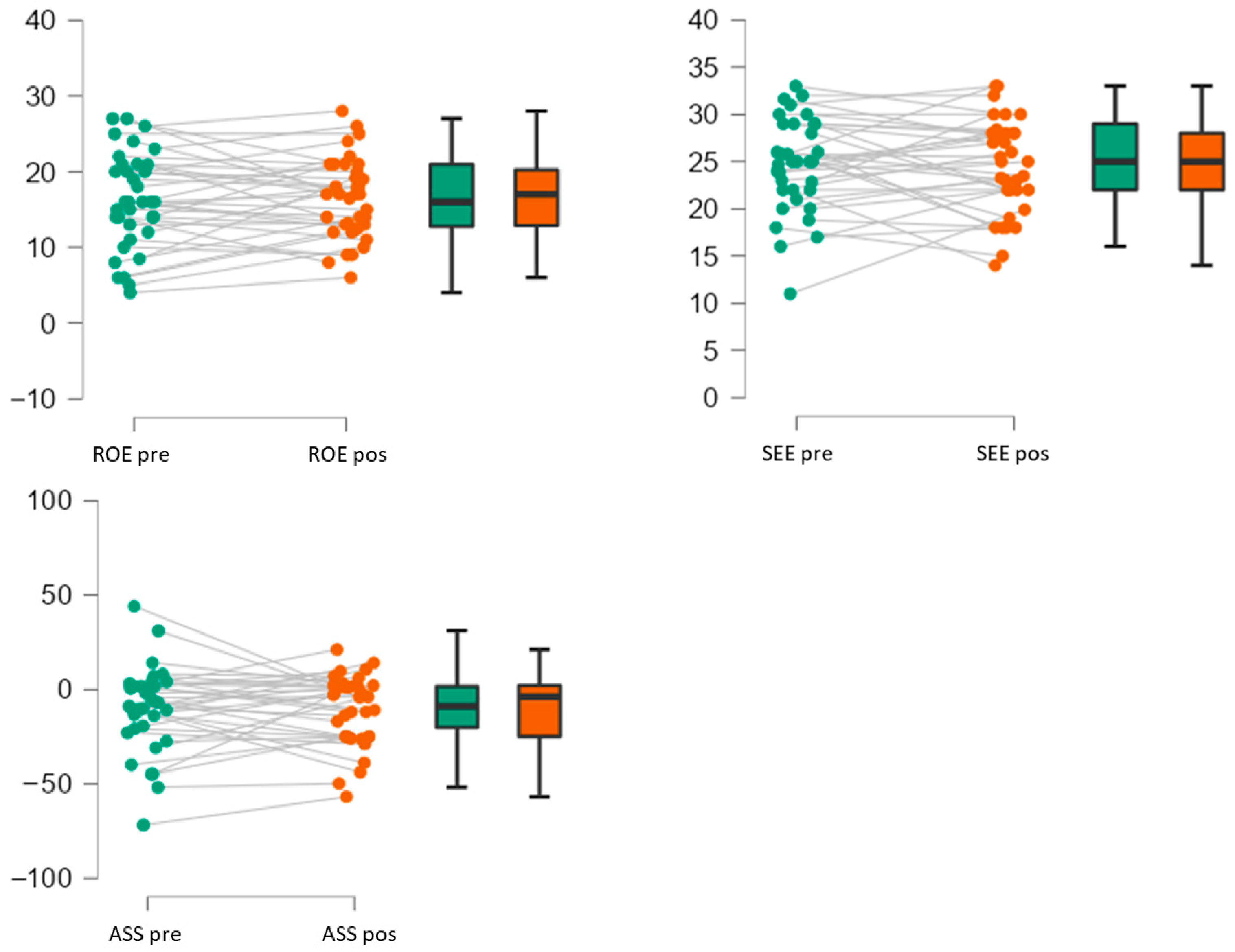

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrahams, L., Pancorbo, G., Primi, R., Santos, D., Kyllonen, P., John, O. P., & De Fruyt, F. (2019). Social-emotional skill assessment in children and adolescents: Advances and challenges in personality, clinical, and educational contexts. Psychological Assessment, 31(4), 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibsereshki, N., Hatamizadeh, N., Sajedi, F., & Kazemnejad, A. (2019). The effectiveness of a resilience intervention program on emotional intelligence of adolescent students with hearing loss. Children, 6(3), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. R., Killian, M., Hughes, J. L., Rush, A. J., & Trivedi, M. H. (2020). The adolescent resilience questionnaire: Validation of a shortened version in U.S. youths. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 606373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsandaux, J., Galéra, C., & Salamon, R. (2021). The association of self-esteem and psychosocial outcomes in young adults: A 10-year prospective study. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(2), 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. (2019). Mediating role of self-esteem and resilience in the association between social exclusion and life satisfaction among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avşar, F., & Alkaya, S. (2017). The effectiveness of assertiveness training for school-aged children on bullying and assertiveness level. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 36, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babić, A., & Tomašić, J. (2023). Ability and trait emotional intelligence: Do they contribute to the explanation of prosocial behaviour? European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(6), 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán, A. B., Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Molero, M. D. M., Martos, Á., Simón, M. D. M., Sisto, M., & Gázquez, J. J. (2021). Emotional intelligence and academic engagement in adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beets, M. W., von Klinggraeff, L., Weaver, R. G., Armstrong, B., & Burkart, S. (2021). Small studies, big decisions: The role of pilot/feasibility studies in incremental science and premature scale-up of behavioral interventions. Pilot Feasibility Studies, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benita, M., Levkovitz, T., & Roth, G. (2017). Integrative emotion regulation predicts adolescents’ prosocial behavior through the mediation of empathy. Learning and Instruction, 50, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, J. A., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2016). Affective social competence in adolescence: Current findings and future directions. Social Development, 26(1), 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cerit, E., & Şimşek, N. (2021). A social skills development training programme to improve adolescents’ psychological resilience and emotional intelligence level. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 35(6), 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiș, A., & Rusu, A. S. (2019). School-based interventions for developing emotional abilities in adolescents: A systematic review. In V. Chiș, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, reflection, development–European proceedings of social and behavioural sciences (pp. 430–438). Future Academy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Coolican, H. (2009). Research methods and statistics in psychology (5th ed.). Hodder Arnold H&S. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, L. D., Fuentes, M. I., & Senra, L. N. C. (2018). Adolescence and self-esteem: Its development from educational institutions. Revista Conrado, 14(64), 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, A. A., Rabiei, L., Afzali, S. M., Hamidizadeh, S., & Masoudi, R. (2016). The effectiveness of assertiveness training on the levels of stress, anxiety, and depression of high school students. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 18(1), e21096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Díaz, L., Fernández-Caminero, G., Hernández-Lloret, C. M., González-González, H., & Álvarez-Castillo, J. L. (2021). Emotional intelligence and executive functions in the prediction of prosocial behavior in high school students: An interdisciplinary approach between neuroscience and education. Children, 8, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick-Smith, A., Dahlberg, E. E., & Thompson, S. C. (2018). Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC Psychology, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, G., Saavedra, E., Riquelme, E., Arriagada, C., & Muñoz, F. (2023). Emotional regulation and culture in school contexts. European Journal of Educational Psychology, 16(2), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M. (2023). Educational psychology: The key to prevention and child-adolescent mental health. Psicothema, 35(4), 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. (1995). Multiple intelligences: Theory in practice. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Gedda-Muñoz, R., Fuentez, Á., Valenzuela, A., Retamal, I., Cruz, M., Badicu, G., Herrera-Valenzuela, T., & Valdés-Badilla, P. (2023). Factors associated with anxiety, depression, and stress levels in high school students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(9), 1776–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golshiri, P., Mostofi, A., & Rouzbahani, S. (2023). The effect of problem-solving and assertiveness training on self-esteem and mental health of female adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychology, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjemdal, O., Vogel, P. A., Solem, S., Hagen, K., & Stiles, T. C. (2011). The relationship between resilience and levels of anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adolescents. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(4), 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 24.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- İlhan, N., Sukut, O., Akhan, L. U., & Batmaz, M. (2016). The effect of nurse education on the self-esteem and assertiveness of nursing students: A four-year longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today, 39, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JASP Team. (2023). JASP (Version 0.18.1) [Computer software]. JASP Team. [Google Scholar]

- Katsantonis, I., McLellan, R., & Marquez, J. (2023). Development of subjective well-being and its relationship with self-esteem in early adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 41(2), 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerby, D. S. (2014). The simple difference formula: An approach to teaching nonparametric correlation. Comprehensive Psychology, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirbiš, A. (2023). Depressive symptoms among Slovenian female tertiary students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of two repeated cross-sectional surveys in 2020 and 2021. Sustainability, 15(18), 13776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koparan, Ş., Öztürk, F., Özkılıç, R., & Şenışık, Y. (2009). An investigation of social self-efficacy expectations and assertiveness in multi-program high school students. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriščiūnaitė, T., & Kern, R. M. (2014). Psycho-educational intervention for adolescents. International Journal of Psychology: Biopsychosocial Approach, 14, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerkkanen, M., Nurmi, J., Vasalampi, K., Virtanen, T., & Torppa, M. (2018). Changes in students’ psychological well-being during transition from primary school to lower secondary school: A person-centered approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 69, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Guo, Y., Lai, W., Wang, W., Li, X., Zhu, L., Shi, J., Guo, L., & Lu, C. (2023). Reciprocal relationships between self-esteem, coping styles, and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: Between-person and within-person effects. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wang, Z. H., & Li, Z. G. (2012). Affective mediators of the influence of neuroticism and resilience on life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Noguero, F., & Gallardo-López, J. A. (2023). Emotional intelligence and adolescence: Perceptions and experiences in the educational field. Pedagogía Social: Revista Interuniversitaria, 43, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheri, M., Alipour, M., Rohban, A., & Garmaroudi, G. (2019). The association of resilience with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adolescent students. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 34(1), 20190050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey, & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2008). Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? American Psychologist, 63(6), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P., & Mehta, B. (2015). Emotional intelligence in relation to satisfaction with life: A study of government secondary school teachers. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 98. [Google Scholar]

- Miething, A., Almquist, Y. B., Edling, C., Rydgren, J., & Rostila, M. (2017). Friendship trust and psychological well-being from late adolescence to early adulthood: A structural equation modeling approach. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 45(3), 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M. D. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Barragán, A. B., del Pino, R. M., & Gázquez, J. J. (2019). Analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence, resilience, and family functioning in adolescents’ sustainable use of alcohol and tobacco. Sustainability, 11, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M. M., Martos, Á., Barragán, A. B., Pérez-Fuentes, M. C., & Gázquez, J. J. (2022). Anxiety and depression from cybervictimization in adolescents: A meta-analysis and meta-regression study. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 14(1), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. C., Martos, Á., Barragán, A. B., Simón, M. M., & Gázquez, J. J. (2021). Emotional intelligence as a mediator in the relationship between academic performance and burnout in high school students. PLoS ONE, 16(6), e0253552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. C., Martos, Á., Pino, R. M., & Gázquez, J. J. (2023). Network analysis of emotional symptoms and their relationship with different types of cybervictimization. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 15(1), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulier, V., Guinet, H., Kovacevic, Z., Bel-Abbass, Z., Benamara, Y., Zile, N., Ourrad, A., Arcella-Giraux, P., Meunier, E., Thomas, F., & Januel, D. (2019). Effects of a life-skills-based prevention program on self-esteem and risk behaviors in adolescents: A pilot study. BMC Psychology, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, N., Granados, R., Durán, C. A., & Galarza, C. (2021). Self-esteem, attitudes toward love, and sexual assertiveness among pregnant adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notario-Pacheco, B., Solera-Martínez, M., Serrano-Parra, M. D., Bartolomé-Gutiérrez, R., García-Campayo, J., & Martínez-europeaVizcaíno, V. (2011). Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-item CD-RISC) in young adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfafman, T. (2017). Assertiveness. In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 1–7). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T. M., Laurence, P. G., Macedo, C. R., & Macedo, E. C. (2021). Resilience programs for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 754115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathus, S. A. (1973). A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behavior Therapy, 4, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X., Gómez-Landero, R. A., & Carrasco-Embun, P. (2023). Effectiveness of an acrobatic gymnastics program to improve emotional intelligence and self-esteem in adolescents. Sustainability, 15(7), 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. J., & Pantaleón, Y. (2019). Psychological predictors of bullying in adolescents: An analysis from the perspective of emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, H., Zhou, Y., Luo, Q., Robert, G. H., Desrivières, S., Quinlan, E. B., Liu, Z., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A. L. W., Bromberg, U., Büchel, C., Flor, H., Frouin, V., Garavan, H., Gowland, P., Heinz, A., Ittermann, B., Martinot, J.-L., Martinot, M.-L. P., … Feng, J. (2019). Adolescent binge drinking disrupts normal trajectories of brain functional organization and personality maturation. NeuroImage: Clinical, 22, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvalcaba, N. A., Gallegos, J., Orozco, M. G., & Bravo, H. R. (2019). Predictive validity of socio-emotional skills on the resilience of Mexican adolescents. Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología, 15(1), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2024). Self-determination theory. In F. Maggino (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J., Munford, R., Thimasarn-Anwar, T., Liebenberg, L., & Ungar, M. (2015). The role of positive youth development practices in building resilience and enhancing wellbeing for at-risk youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 42, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasagawa, S., & Essau, C. A. (2022). Relationship between social anxiety symptoms and behavioral impairment in adolescents: The moderating role of perfectionism and learning motivation. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 15(2), 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeps, K., Tamarit, A., Postigo, S., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2021). The long-term effects of emotional competencies and self-esteem on adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English Edition), 26(2), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I. (2021). Towards an integrative taxonomy of social-emotional competences. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 515313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón-Saiz, M. J., Fuentes-Chacón, R. M., Garrido-Abejar, M., Serrano-Parra, M. D., Larrañaga-Rubio, E., & Yubero-Jiménez, S. (2018). Influence of resilience on health-related quality of life in adolescents. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition), 28(5), 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrove, M., Romundstad, P., & Indredavik, M. S. (2013). Resilience, lifestyle and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescence: The Young-HUNT study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, F., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano-Hermoso, M. D., Ruiz-Frutos, C., Fagundo-Rivera, J., Gómez-Salgado, J., García-Iglesias, J. J., & Romero-Martín, M. (2020). Emotional intelligence and its relationship with emotional well-being and academic performance: The vision of high school students. Children, 7, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-León, J. L., & Caycho, T. (2017). The Omega coefficient: An alternative method for reliability estimation. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, 15, 625–627. [Google Scholar]

- Vovk, V. G. (1993). A logic of probability, with application to the foundations of statistics. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 55, 317–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Adolescent health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Young, J. F., Kranzler, A., Gallop, R., & Mufson, L. (2012). Interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training: Effects on school and social functioning. School Mental Health, 4(4), 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| RES Pos | SEA Pos | OEA Pos | UOE Pos | ROE Pos | SEE Pos | ASS Pos | ||

| RES pre | - | 0.35 * | −0.29 | 0.60 *** | 0.41 * | 0.60 *** | 0.36 * | RES pos |

| SEA pre | 0.50 ** | - | 0.02 | 0.42 * | 0.68 *** | 0.46 ** | 0.21 | SEA pos |

| OEA pre | 0.01 | 0.20 | - | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.38 * | −0.15 | OEA pos |

| UOE pre | 0.53 *** | 0.51 ** | −0.09 | - | 0.49 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.34 * | UOE pos |

| ROE pre | 0.52 ** | 0.60 *** | 0.03 | 0.46 ** | - | 0.39* | 0.28 | ROE pos |

| SEE pre | 0.54 *** | 0.27 | −0.32 | 0.34 * | 0.33 * | - | 0.48 ** | SEE pos |

| ASS pre | 0.61 *** | 0.21 | −0.17 | 0.43 * | 0.42 * | 0.49 ** | - | ASS pos |

| RES pre | SEA pre | OEA pre | UOE pre | ROE pre | SEE pre | ASS pre |

| Pre | Post | W | z | p | rrb | 95% CI for rrb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Resilience | 23.59 | 7.06 | 24.77 | 7.19 | 234.50 | −1.077 | 0.285 | −0.212 | −0.537 | 0.169 |

| SEA | 18.61 | 5.50 | 18.83 | 5.82 | 291.50 | −0.652 | 0.519 | −0.125 | −0.462 | 0.244 |

| OEA | 18.92 | 6.25 | 19.95 | 5.28 | 233.00 | −0.580 | 0.568 | −0.117 | −0.474 | 0.272 |

| UOE | 17.58 | 6.05 | 19.13 | 6.73 | 173.50 | −2.120 | 0.035 | −0.417 | −0.680 | −0.058 |

| ROE | 16.21 | 6.31 | 16.43 | 5.28 | 301.00 | −0.229 | 0.824 | −0.044 | −0.401 | 0.323 |

| Self-esteem | 24.59 | 4.91 | 24.50 | 4.93 | 280.50 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | −0.372 | 0.372 |

| Assertiveness | −10.41 | 22.50 | −10.77 | 18.66 | 319.00 | 0.066 | 0.954 | 0.013 | −0.352 | 0.374 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina Moreno, P.; Simón Márquez, M.d.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Molero Jurado, M.d.M. Key Competencies for Adolescent Well-Being: An Intervention Program in Secondary Education. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110219

Molina Moreno P, Simón Márquez MdM, Pérez-Fuentes MdC, Molero Jurado MdM. Key Competencies for Adolescent Well-Being: An Intervention Program in Secondary Education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(11):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110219

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina Moreno, Pablo, María del Mar Simón Márquez, María del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes, and María del Mar Molero Jurado. 2025. "Key Competencies for Adolescent Well-Being: An Intervention Program in Secondary Education" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 11: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110219

APA StyleMolina Moreno, P., Simón Márquez, M. d. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. d. C., & Molero Jurado, M. d. M. (2025). Key Competencies for Adolescent Well-Being: An Intervention Program in Secondary Education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(11), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110219