Measuring Cyber Interpersonal Violence in Adolescents: Development and Validation of the CyIVIA Instrument

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- Literature review

- (b)

- Focus group with young adults

- (c)

- Review by experts

- Victimization (10 items): suffering from different forms of abusive behavior using technological devices.

- Perpetration (10 items): perpetrating different forms of abusive behavior using technological devices.

- Bystander knowledge of perpetration (10 items): Knowing someone who perpetrates different forms of abusive behavior using technological devices.

- Bystander knowledge of victimization (10 items): Knowing someone who suffers from different forms of abusive behavior using technological devices.

- (d)

- Creation of the final scale

2.1. Procedure

| Victimization items of Cyber Interpersonal Violence |

| I received insulting messages, photos or images They impersonated me and used my social media I received unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/message/social media ** They posted private content about me without permission ** They accessed my social media or email without permission They recorded a video or took photos of me while someone made fun of me or hurt me ** Posted and/or shared photos of me naked or with little clothing on the internet * I was pressured to talk about sex online * They spread rumours or false things about me They used my passwords (phone, social networks, email) to check my accounts without permission |

| Perpetration items of Cyber Interpersonal Violence |

| I sent insulting messages, photos or images I pretended to be someone else and used their social media I sent unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/message/social media * I posted private content about someone else without permission Accessed someone else’s social media or email without permission I recorded a video or took photos of someone while they mocked and/or hurt another person Posted and/or shared photos of someone undressed or with little clothing * I pressured someone to talk online about sex * Spread rumours or false things about someone else Used someone else’s passwords (phone, social media, email) to view their accounts without permission * |

| Bystander’s perpetration items of Cyber Interpersonal Violence |

| I know and/or have seen someone send insulting messages, photos or images I know and/or watched someone impersonate someone else while using their social media I know and/or watched someone send unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/text/social media I know and/or watched someone post private content about other people without permission ** I know and/or watched someone access someone else’s social media email without permission ** I know and/or watched someone recording a video or taking photos while mocking and/or hurting another person I know and/or saw someone posting and/or sharing photos of a person undressed or wearing little clothing I know and/or watched someone pressure another person to talk online about sex ** I know and/or have watched someone spread rumours or false things about a person ** I know and/or watched someone use someone else’s passwords (phone, social media, email) to check their accounts without permission ** |

| Bystanders’ victimization items of Cyber Interpersonal Violence |

| I know and/or have seen someone receive insulting messages, photos or images I know and/or watched someone pretend to be that person and use their social media I know and/or watched someone receive unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/text/social media I know and/or watched someone who posted private content without permission ** I know and/or have seen someone who has accessed social media or email without permission ** I know and/or watched someone they took a video of or took photos of while mocking the person or hurting them I know and/or watched someone who has posted and/or shared nude or scantily clad photos of themselves I know and/or watched someone who was pressured to talk about sex online ** I know and/or watched someone about whom rumours, or false things have spread ** I know and/or have helped someone who used passwords (phone, social media, email) to verify their accounts without permission |

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.1.1. Reliability

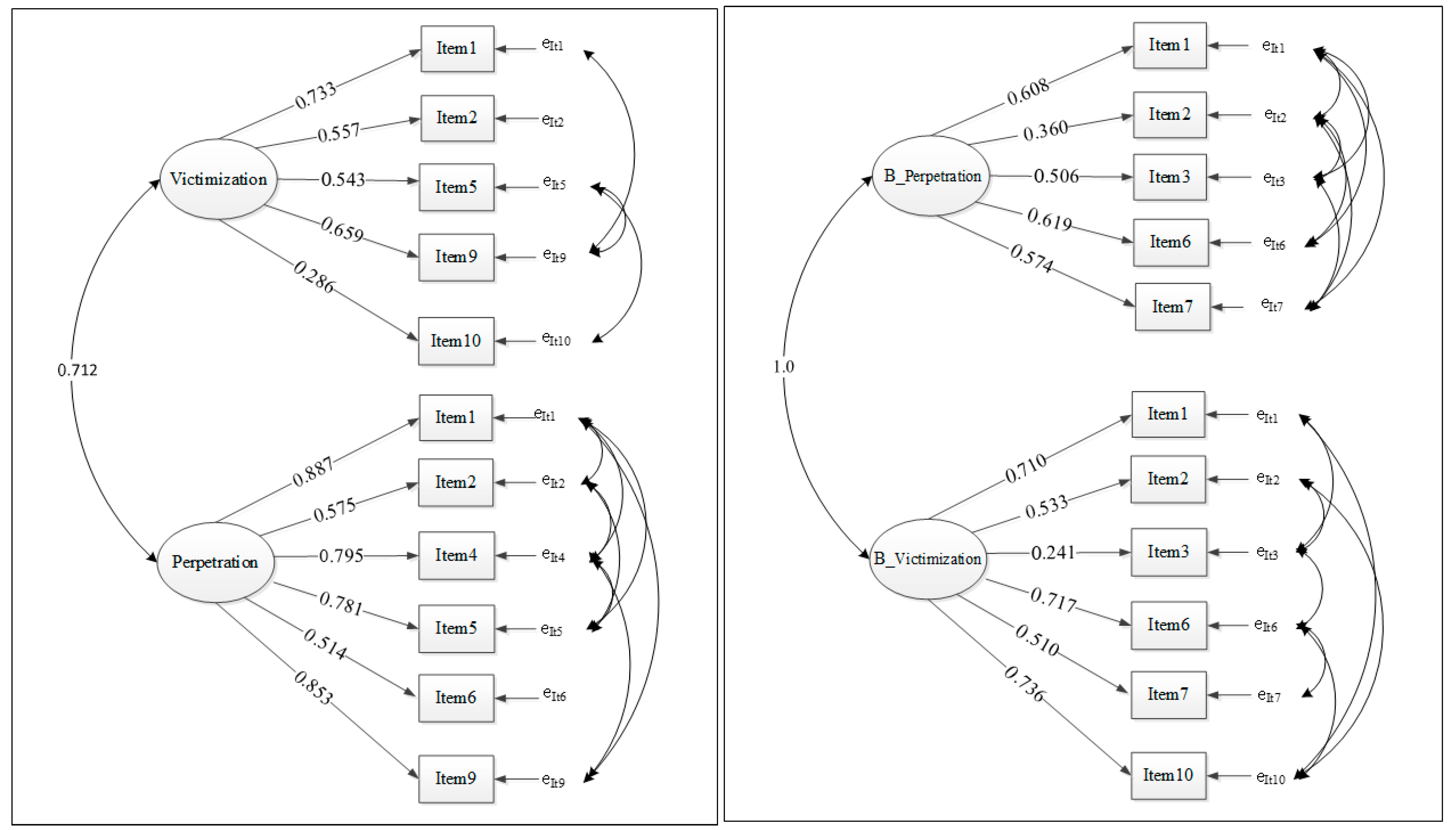

3.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.1.3. Prevalence of Cyber Interpersonal Violence

3.1.4. Variables Associated with CIV

3.1.5. Anxiety, Depression, Somatization and CyIVIA

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSI-18 | Brief Symptom Inventory 18 |

| CCB_A | Cyberbullying Questionnaires CCB_A (agressor) |

| CCB_V | Cyberbullying Questionnaires CCB_V (victim) |

| CDA | cyber dating abuse |

| CDAQ | Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire |

| CDVI | Cyber Dating Violence Inventory |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CIV | cyber interpersonal violence |

| CYB-AGS | Adolescent Cyber-Aggressor Scale |

| CyIVIA | Cyber Interpersonal Violence Instrument for Adolescents |

| EFA | exploratory factor analysis |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

References

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2011). IBM SPSS Amos 20 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation, SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry, A. C., Farrington, D. P., & Sorrentino, A. (2016). Cyberbullying in youth: A pattern of disruptive behaviour. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, K., & Jurasz, O. (2024). Digital and online violence: International perspectives. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 38(2), 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual (Vol. 6). Multivariate Software, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Borrajo, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., Pereda, N., & Calvete, E. (2015). The development and validation of the cyber dating abuse questionnaire among young couples. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Buelga, S., & Pons, J. (2012). Agresiones entre Adolescentes a través del Teléfono Móvil y de Internet. Psychosocial Intervention, 21(1), 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelga, S., Postigo, J., Martínez-Ferrer, B., Cava, M.-J., & Ortega-Barón, J. (2020). Cyberbullying among adolescents: Psychometric properties of the CYB-AGS cyber-aggressor Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., Estévez, A., Villardón, L., & Padilla, P. (2010). Cyberbullying in adolescents: Modalities and aggressors’ profile. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavarro, M. C., Nazaré, B., & Pereira, M. (2017). Inventário de sintomas psicopatológicos 18 (BSI-18). In M. M. Gonçalves, M. R. Simões, & L. Almeida (Eds.), Psicologia clínica e da saúde: Instrumentos de avaliação (pp. 115–130). Editora Pactor. [Google Scholar]

- Caridade, S., & Braga, T. (2019). Versão portuguesa do Cyber Dating Abuse Questionaire (CDAQ)–Questionário sobre Ciberabuso no Namoro (CibAN): Adaptação e propriedades psicométricas. Análise Psicológica, 37, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Pereira, F., de Matos, M. A. V., & Oliveira, Á. M. d. C. G. (2015). Cyber-crimes against adolescents: Bridges between a psychological and a design approach. In Handbook of research on digital crime, cyberspace security, and information assurance (pp. 211–230). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck, D., Waechter, N., & d’Haenens, L. (2023). Predicting self-reported depression and health among adolescents: Time spent online mediated by digital skills and digital activities. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 26(10), 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., Thompson, F., Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., & Brighi, A. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European cyberbullying intervention project questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L. R. (1993). Brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (4th ed.). National Computer Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, J. J., Pyżalski, J., & Cross, D. (2009). Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying: A theoretical and conceptual review. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, E., Donnerstein, E., Kowalski, R., Lin, C. A., & Parti, K. (2017). Defining cyberbullying. Pediatrics, 140(Suppl. 2), S148–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, E., Ortega-Rivera, J., Ojeda, M., Sánchez-Jiménez, V., & Del Rey, R. (2022). Violence among adolescents: A study of overlapping of bullying, cyberbullying, sexual harassment, dating violence and cyberdating violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 134, 105921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garett, R., Lord, L. R., & Young, S. D. (2016). Associations between social media and cyberbullying: A review of the literature. Mhealth, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffner, R. (2016). Partner aggression versus partner abuse terminology: Moving the field forward and resolving controversies. Journal of Family Violence, 31(8), 923–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., Liu, J., & Wang, J. (2021). Cyberbullying roles among adolescents: A social-ecological theory perspective. Journal of School Violence, 20(2), 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelwood, S. D., & Koon-Magnin, S. (2013). Cyber stalking and cyber harassment legislation in the United States: A qualitative analysis. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 7(2), 155. [Google Scholar]

- Hldalgo-Rasmussen, C. A., Javier-Juárez, P., Zurlta-Agullar, K., Yanez-Peñuñuri, L., Franco-Paredes, K., & Chávez-Flores, V. (2020). Adaptación transcultural del” Cuestionario de Abuso Cibernético en la Pareja” (CDAQ) para adolescentes mexicanos. Behavioral Psychology = Psicología Conductual, 28(3), 435–453. [Google Scholar]

- Jadambaa, A., Thomas, H. J., Scott, J. G., Graves, N., Brain, D., & Pacella, R. (2019). Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(9), 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyagobi, S., Munusamy, S., Kamaluddin, M. R., Ahmad Badayai, A. R., & Kumar, J. (2022). Factors influencing negative cyber-bystander behavior: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 965017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W. (2020). A study on the cause analysis of cyberbullying in Korean adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2001). Psychological testing: Principles, applications, and issues. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, L. (2020). Cyber dating abuse: Assessment, prevalence, and relationship with offline violence in young Chileans. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(5), 1681–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Wang, P., Martin-Moratinos, M., Bella-Fernandez, M., & Blasco-Fontecilla, H. (2024). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(9), 2895–2909. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Y., Zhou, Y., Lian, X., & Dong, X. (2022). Cyber violence caused by the disclosure of route information during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B., Caridade, S., Araújo, I., & Faria, P. L. (2022). Mapping the cyber interpersonal violence among young populations: A scoping review. Social Sciences, 11(5), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B., de Faria, P. L., Araújo, I., & Caridade, S. (2024). Cyber interpersonal violence: Adolescent perspectives and digital practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, C., Trombetta, T., Negri, R., & Zanetti, M. A. (2024). The role of parental mediation in cybervictimization among adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, Publication Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações. ReportNumber, Lda. [Google Scholar]

- Marret, M. J., & Choo, W. Y. (2017). Factors associated with online victimisation among Malaysian adolescents who use social networking sites: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 7(6), e014959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M., Bianchi, D., Chirumbolo, A., & Baiocco, R. (2018). The cyber dating violence inventory. Validation of a new scale for online perpetration and victimization among dating partners. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaré, B., Pereira, M., & Canavarro, M. C. (2017). Avaliação breve da psicossintomatologia: Análise fatorial confirmatória da versão portuguesa do Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI 18). Análise Psicológica, 35(2), 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, F., Pereira, F., & Matos, M. (2014). Cyber-aggression among Portuguese adolescents: A study on perpetration, victim offender overlap and parental supervision. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 8(2), 94. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, L. J., Allan, A., & Cross, D. (2017). Adolescent bystander behavior in the school and online environments and the implications for interventions targeting cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 16(4), 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F., Spitzberg, B. H., & Matos, M. (2016). Cyber-harassment victimization in Portugal: Prevalence, fear and help-seeking among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A., & Henry, N. (2018). Policing technology-facilitated sexual violence against adult victims: Police and service sector perspectives. Policing and Society, 28(3), 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo-Catalan, A., & Mayor-Buzon, V. (2020). Adolescent bystanders witnessing cyber violence against women and girls: What they observe and how they respond. Violence against Women, 26(15–16), 2024–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, I., Jaureguizar, J., Dosil, M., & Galende, N. (2022). Measuring cyber dating violence: Reliability and validity of the Escala de CiberViolencia en Parejas Adolescentes (Cib-VPA) in Spanish young adults. Clínica y Salud, 33(3), 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-deArriba, M. L., Santos, C., Cunha, O., Sánchez-Jiménez, V., & Caridade, S. (2024). Relationship between cyber and in-person dating abuse: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 77, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, V., Muñoz-Fernández, N., & Ortega-Ruíz, R. (2015). “Cyberdating Q_A”: An instrument to assess the quality of adolescent dating relationships in social networks. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Jiménez, V., Rodríguez de Arriba, M. L., Stefanelli, F., & Nocentini, A. (2023). Cyber Dating Violence Instrument for Teens (CyDAV-T): Dimensional structure and relative item discrimination. Psicothema, 2(35), 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. K., López-Castro, L., Robinson, S., & Görzig, A. (2019). Consistency of gender differences in bullying in cross-cultural surveys. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, M., Przepiórka, A., & Błachnio, A. (2024). Factors contributing to the defending behavior of adolescent cyberbystanders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 162, 108463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (2014). The dark side of relationship pursuit: From attraction to obsession and stalking. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Winarti, E., & Saudah, N. (2023). Multi-dimensional impact of cyber gender-based violence: Examining physical, mental, social, cultural, and economic consequences. Gaceta Médica de Caracas, 131(Suppl. 4), S591–S598. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C., Huang, S., Evans, R., & Zhang, W. (2021). Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 634909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumalde, E. C., González, L. F., Sola, I. O., Garagorri, J. M. M., & Cabrera, J. G. (2021). Validación de un cuestionario para evaluar el abuso en relaciones de pareja en adolescentes (CARPA), sus razones y las reacciones. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 8(1), 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, J. M., Dank, M., Yahner, J., & Lachman, P. (2013). The rate of cyber dating abuse among teens and how it relates to other forms of teen dating violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(7), 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1. I sent insulting messages, photos or images | 0.689 | |

| 2.2. I pretended to be someone else and used their social media | 0.828 | |

| 2.4. I posted private content about someone else without permission | 0.857 | |

| 2.5. Accessed someone else’s social media or email without permission | 0.864 | |

| 2.6. I recorded a video or took photos of someone while they mocked and/or hurt another person | 0.509 | |

| 2.9. Spread rumours or false things about someone else | 0.860 | |

| 1.1. I received insulting messages, photos or images | 0.578 | |

| 1.2. They impersonated me and used my social media | 0.589 | |

| 1.5. They accessed my social media or email without permission | 0.801 | |

| 1.9. They spread rumours or false things about me | 0.623 | |

| 1.10. They used my passwords (phone, social networks, email) to check my accounts without permission | 0.784 | |

| Eigenvalues | 1.810 | |

| % of Variance | 44.52 | 16.46 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1. I know and/or have seen someone send insulting messages, photos or images | 0.798 | |

| 3.2. I know and/or watched someone impersonate someone else while using their social media | 0.865 | |

| 3.3. I know and/or watched someone send unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/text/social media | 0.745 | |

| 3.6. I know and/or watched someone recording a video or taking photos while mocking and/or hurting another person | 0.596 | |

| 3.7. I know and/or saw someone posting and/or sharing photos of a person undressed or wearing little clothing | 0.770 | |

| 4.1. I know and/or have seen someone receive insulting messages, photos or images | 0.739 | |

| 4.2. I know and/or watched someone pretend to be that person and use their social media | 0.704 | |

| 4.3. I know and/or watched someone receive unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/text/social media | 0.685 | |

| 4.6. I know and/or watched someone they took a video of or took photos of while mocking the person or hurting them | 0.535 | |

| 4.7. I know and/or watched someone who has posted and/or shared nude or scantily clad photos of themselves | 0.567 | |

| 4.10. I know and/or have helped someone who used passwords (phone, social media, email) to verify their accounts without permission | 0.634 | |

| Eigenvalues | 5.036 | 1.307 |

| % of Variance | 45.78 | 11.88 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD | Cronbach Alpha | 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetration | 6.00 | 22.00 | 7.42 + 2.68 | 0.851 | 1.000 | 0.629 ** |

| Victimization | 5.00 | 16.00 | 6.35 + 2.30 | 0.712 | 1.000 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD | Cronbach Alpha | 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byst_Victimization | 5.00 | 19.00 | 5.90 ± 2.23 | 0.827 | 1.000 | 0.633 ** |

| Byst_Perpetration | 6.00 | 20.00 | 6.66 ± 1.75 | 0.728 | 1.000 |

| It Happened at Least on Time in the Last Six Months | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | χ2 | p | ||

| 1. I received insulting messages, photos or images | 13% | 48.5% | 51.5% | 1.323 | 0.25 |

| 2. They impersonated me and used my social media | 9.9% | 68.0% | 32.0% | 1.204 | 0.272 |

| 3. I received unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/message/social media ** | 9.9% | 32.0% | 68.0% | 7.512 | 0.006 |

| 4. They posted private content about me without permission ** | 9.9% | 32.0% | 68.0% | 7.512 | 0.006 |

| 5. They accessed my social media or email without permission | 15.4% | 61.5% | 38.5% | 0.277 | 0.599 |

| 6. They recorded a video or took photos of me while someone made fun of me or hurt me ** | 6.3% | 62.5% | 37.5% | 0.161 | 0.688 |

| 7. Posted and/or shared photos of me naked or with little clothing on the internet * | 0.8% | 100% | 0% | 1.477 | 0.224 |

| 8. I was pressured to talk about sex online * | 1.6% | 100% | 0% | 2.979 | 0.084 |

| 9. They spread rumours or false things about me | 33.6% | 40.0% | 60.0% | 16.446 | <0.001 |

| 10. They used my passwords (phone, social networks, email) to check my accounts without permission | 6.7% | 47.1% | 52.9% | 0.847 | 0.357 |

| It Happened at Least on Time in the Last Six Months | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | χ2 | p | ||

| 1. I sent insulting messages, photos or images | 8.7% | 81.8% | 18.2% | 5.739 | 0.017 |

| 2. I pretended to be someone else and used their social media | 3.2% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.201 | 0.654 |

| 3. I sent unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/message/social media * | 0.8% | 100% | 0% | 1.477 | 0.224 |

| 4. I posted private content about someone else without permission | 2.4% | 33.3% | 66.7% | 1.496 | 0.221 |

| 5. Accessed someone else’s social media or email without permission | 3.2% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.201 | 0.654 |

| 6. I recorded a video or took photos of someone while they mocked and/or hurt another person | 4.7% | 100% | 0% | 9.232 | 0.002 |

| 7. Posted and/or shared photos of someone undressed or with little clothing * | 0.8% | 100% | 0% | 1.477 | 0.224 |

| 8. I pressured someone to talk online about sex * | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 9. Spread rumours or false things about someone else | 7.5% | 47.4% | 52.6% | 0.900 | 0.343 |

| 10. Used someone else’s passwords (phone, social media, email) to view their accounts without permission * | 0.8% | 100% | 0% | 1.477 | 0.224 |

| It Happened at Least on Time in the Last Six Months | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | χ2 | p | ||

| 1. I know and/or have seen someone send insulting messages, photos or images | 13% | 66.7% | 33.3% | 1.248 | 0.264 |

| 2. I know and/or watched someone impersonate someone else while using their social media | 16.6% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 1.226 | 0.268 |

| 3. I know and/or watched someone send unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/text/social media | 7.5% | 52.6% | 47.4% | 0.217 | 0.641 |

| 4. I know and/or watched someone post private content about other people without permission ** | 10.3% | 34.6% | 65.4% | 6.331 | 0.012 |

| 5. I know and/or watched someone access someone else’s social media email without permission ** | 5.9% | 33.3% | 66.7% | 3.881 | 0.049 |

| 6. I know and/or watched someone recording a video or taking photos while mocking and/or hurting another person | 11.1% | 57.1% | 42.9% | 0.004 | 0.949 |

| 7. I know and/or saw someone posting and/or sharing photos of a person undressed or wearing little clothing | 6.7% | 47.1% | 52.9% | 0.847 | 0.357 |

| 8. I know and/or watched someone pressure another person to talk online about sex ** | 4% | 20.0% | 80.0% | 6.066 | 0.014 |

| 9. I know and/or have watched someone spread rumours or false things about a person ** | 24.9% | 36.5% | 63.5% | 15.448 | <0.001 |

| 10. I know and/or watched someone use someone else’s passwords (phone, social media, email) to check their accounts without permission ** | 4% | 40.0% | 60.0% | 1.338 | 0.247 |

| It Happened at Least on Time in the Last Six Months | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | χ2 | p | ||

| 1. I know and/or have seen someone receive insulting messages, photos or images | 14.6% | 56.8% | 43.2% | 0.016 | 0.899 |

| 2. I know and/or watched someone pretend to be that person and use their social media | 4.7% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.307 | 0.580 |

| 3. I know and/or watched someone receive unwanted sexual images/messages and/or requests via email/text/social media | 6.3% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.416 | 0.519 |

| 4. I know and/or watched someone who posted private content without permission ** | 4.3% | 18.2% | 81.8% | 7.361 | 0.007 |

| 5. I know and/or have seen someone who has accessed social media or email without permission ** | 5.1% | 38.5% | 61.5% | 2.080 | 0.149 |

| 6. I know and/or watched someone they took a video of or took photos of while mocking the person or hurting them | 8.3% | 47.6% | 52.4% | 0.955 | 0.328 |

| 7. I know and/or watched someone who has posted and/or shared nude or scantily clad photos of themselves | 6.3% | 25.0% | 75.0% | 7.487 | 0.006 |

| 8. I know and/or watched someone who was pressured to talk about sex online ** | 3.2% | 0% | 100% | 11.272 | <0.001 |

| 9. I know and/or watched someone about whom rumours, or false things have spread ** | 19.4% | 38.8% | 61.2% | 8.924 | 0.003 |

| 10. I know and/or have helped someone who used passwords (phone, social media, email) to verify their accounts without permission | 0.8% | 100% | 0% | 1.477 | 0.224 |

| Gender | N (%) | M (SD) | U | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | Male | 146 (57.7) | 6.16 ± 2.35 | 6275.0 | 0.003 |

| Female | 107 (42.3) | 6.64 ± 2.22 | |||

| Perpetration | Male | 146 (57.7) | 7.26 ± 2.99 | 6082.0 | <0.001 |

| Female | 107 (42.3) | 7.65 ± 2.16 | |||

| Byst_victimization | Male | 146 (57.7) | 5.92 ± 2.42 | 7631.0 | 0.691 |

| Female | 107 (42.3) | 5.86 ± 1.95 | |||

| Byst_perpetration | Male | 146 (57.7) | 6.62 ± 1.92 | 7007.5 | 0.064 |

| Female | 107 (42.3) | 6.73 ± 1.49 |

| Grade Level | N (%) | M (SD) | H (3) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | 6th grade | 107 (42.3) | 5.93 ± 1.56 | 29.96 | <0.001 |

| 7th grade | 41 (16.2) | 5.80 ± 2.42 | |||

| 8th grade | 91 (36.0) | 7.19 ± 2.76 | |||

| 9th grade | 14 (5.5) | 5.86 ± 2.18 | |||

| Perpetration | 6th grade | 107 (42.3) | 6.96 ± 1.47 | 30.15 | <0.001 |

| 7th grade | 41 (16.2) | 6.51 ± 1.85 | |||

| 8th grade | 91 (36.0) | 8.56 ± 3.72 | |||

| 9th grade | 14 (5.5) | 6.29 ± 0.47 | |||

| Byst_victimization | 6th grade | 107 (42.3) | 5.24 ± 0.61 | 39.20 | <0.001 |

| 7th grade | 41 (16.2) | 5.73 ± 2.64 | |||

| 8th grade | 91 (36.0) | 6.81 ± 2.98 | |||

| 9th grade | 14 (5.5) | 5.43 ± 0.76 | |||

| Byst_perpetration | 6th grade | 107 (42.3) | 6.45 ± 0.85 | 8.04 | 0.045 |

| 7th grade | 41 (16.2) | 6.15 ± 0.53 | |||

| 8th grade | 91 (36.0) | 7.14 ± 2.63 | |||

| 9th grade | 14 (5.5) | 6.71 ± 1.44 |

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Victimization | 6.36 ± 2.30 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Perpetration | 7.43 ± 2.68 | 0.629 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Byst_victimization | 5.90 ± 2.23 | 0.470 ** | 0.715 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Byst_perpetration | 6.66 ± 1.75 | 0.390 ** | 0.615 ** | 0.534 ** | 1 | |||

| 5. BSI_Somatization | 9.57 ± 4.79 | 0.475 ** | 0.467 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.238 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. BSI_Depression | 8.90 ± 4.05 | 0.468 ** | 0.447 ** | 0.260 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.891 ** | 1 | |

| 7. BSI_Anxiety | 9.09 ± 4.53 | 0.498 ** | 0.437 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.912 ** | 0.877 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Machado, B.; Araújo, I.; Jesus, R.F.; Vilhena, E.; Castro, R.; de Faria, P.L.; Caridade, S. Measuring Cyber Interpersonal Violence in Adolescents: Development and Validation of the CyIVIA Instrument. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110218

Machado B, Araújo I, Jesus RF, Vilhena E, Castro R, de Faria PL, Caridade S. Measuring Cyber Interpersonal Violence in Adolescents: Development and Validation of the CyIVIA Instrument. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(11):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110218

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachado, Bárbara, Isabel Araújo, Rui Ferreira Jesus, Estela Vilhena, Ricardo Castro, Paula Lobato de Faria, and Sónia Caridade. 2025. "Measuring Cyber Interpersonal Violence in Adolescents: Development and Validation of the CyIVIA Instrument" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 11: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110218

APA StyleMachado, B., Araújo, I., Jesus, R. F., Vilhena, E., Castro, R., de Faria, P. L., & Caridade, S. (2025). Measuring Cyber Interpersonal Violence in Adolescents: Development and Validation of the CyIVIA Instrument. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(11), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110218