Conceptualisation of Digital Wellbeing Associated with Generative Artificial Intelligence from the Perspective of University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Relationship Between Digital Wellbeing and Artificial Intelligence

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Sample

2.2. Research Instrument

2.3. Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Digital Wellbeing in the Narrow Sense

Don’t spend all your time on AI.Set a time limit on using the tools and be mindful of your mental and physical wellbeing.Don’t let working with AI consume you entirely. Set limits on your time spent in the virtual environment.Think about screentime and its distribution during the day

Excessive interaction with AI tools can lead to digital stress or fatigue. Set limits and engage in activities outside the digital world.AI will talk to you for hours and is available around the clock. But don’t overdo it; learn to turn off the tools in time. Sufficient offline time is essential for your mental wellbeing.

Addiction to AI can easily arise. So, we should not rely too much on language models for personal relationships or emotions.Create healthy habits: Approach AI as an everyday tool, but don’t let it become an addiction. Scheduling regular breaks from technology will help maintain balance.Beware of addictions. Talking to AI can take a toll on your psyche.

Set time limits for working or playing with AI—as with social networking, digital overload can occur.Promote digital wellbeing—Balance time with AI technology with offline activities. Prolonged use of AI can lead to digital fatigue or impaired concentration.

Don’t use AI as a substitute for personal interaction—Using AI is excellent for a variety of tasks, but don’t forget the importance of personal contact and interpersonal relationships.Be critical of how AI interacts with you. AI may seem human, but it’s not a real person; don’t form emotional attachments to it.Don’t confuse a conversation with a generative AI with interacting with a real person. It may seem empathetic, but it doesn’t understand emotion or context. It can mislead us with unrealistic interpersonal relationships.AI may be pleasant, non-judgmental and always available, but it is not human. If AI replaces real contacts, you may gradually lose social skills, empathy or confidence in communication. Maintain natural contact with the people around you.

AI should not play the role of our friend, therapist or otherwise close person. Social contact is essential to us and should not be replaced by chat shoes.Keep the human dimension—Remember that AI is a tool, not a replacement for human creativity, intuition and decision-making. Use AI as a helper, not as a substitute for your judgment.

Don’t expect human understanding—AI can simulate conversation but doesn’t experience emotion or perceive context like a human. Use it as a tool, not as a substitute for interpersonal communication.Although it may seem empathetic or “human,” AI has no emotions or intentions. Let’s keep a healthy distance.AI cannot replace humans in terms of empathy and the emotional side.AI can be persuasive, sometimes even human. It can respond with humour, compassion and empathy, but it is all just the result of computation. It cannot understand, feel or take responsibility. Knowing that you are communicating with an algorithm helps you avoid unrealistic expectations and emotional attachment.

Define when and how you use AI. Automate routine tasks but retain human decision-making where empathy and moral judgment are needed.Reflect on your relationship with AI. Everyone has their take on it, everyone uses AI for different things, at other times, with varying communication styles. The main thing is to realise what applies to you! Find your style, or feel free not to use AI. The main thing is your comfort.Always know why you use AI and don’t waste time on aimless questioning.

AI can complement your work, but it should not completely replace it.AI should help, not replace human thinking. Important decisions should always be thought through and thoroughly verified.Be aware of how AI affects your emotional health, concentration and relationships. Too much reliance on AI can affect your wellbeing and self-confidence. Keep in mind the impact of AI on society and interpersonal relationships.

3.2. The Relationship Between AI and Thinking in the Context of Wellbeing

AI can be a great helper, but users must still actively develop their thinking and creativity. AI should complement human creativity, not replace it. Human creativity, empathy and originality are irreplaceable.The user should only use AI when necessary. Tools should only play the role of an assistant.Use AI to improve efficiency—Use technology only for tasks that help you, and don’t think you have to spend all your time with AI.Set a clear goal, formulate questions thoughtfully, and organise your deliverables—you’ll save time and energy. The user should think of generative AI as a tool supporting thinking and creativity, not as an authority or a substitute for their judgment.

AI does not have consciousness, opinions or human values. It is essential to distinguish between a cue and a decision—that remains up to you.Holding humans accountable for the content they create.AI can be a great help but doesn’t replace your creativity, judgment, or ethical responsibility.We shouldn’t use AI for critical issues, but our minds. We should properly combine our experience and knowledge with AI’s answers.You are still responsible for your decisions, not the AI.

AI may not always be right. Facts need to be verified from multiple sources.Generative AI can produce false or fabricated information. Always verify information.Verify that not all sources on which AI bases its answers are relevant, and even when it does cite sources, its accuracy cannot be entirely relied upon.Check the facts: AI can be persuasive, but not always accurate. Verify necessary information from trusted sources.

Don’t rely on AI with everything: Learn beyond it—develop your skills, knowledge and creativity without assistance.AI can inspire, but we can’t let it diminish our creativity and creative process.We shouldn’t use AI as a substitute for our creativity, but only as an auxiliary supplement to complement our minds.

AI can support creativity and analysis, but should not replace one’s judgment, study or research.

Be transparent: If you use AI to create content, inform others about it and do not try to pass off AI output as your work.If the output you’re sharing was created (in whole or in part) with the help of AI, it’s a good idea to make that clear. This ensures fairness and credibility and helps spread digital literacy in the community.We should be transparent if we use the content generated. We are ensuring fairness to others.Acknowledge if you’ve used AI to write text or help you with an assignment.

3.3. Environmental Aspects

Don’t use AI to create violent, harmful or explicit content.Don’t abuse AI: Don’t use AI to develop harmful, hateful or manipulative content.AI tools should not be used to create hate speech or offensive or discriminatory content.

Don’t use AI to generate illegal content or fake news.Do not use AI to deceive, mislead or spread misinformation.Do not use AI to create hoaxes, fraudulent news or manipulative text or images.We should never use AI to spread misinformation, deception or manipulation. We must respect copyright and ethical principles.

Avoiding the overuse of AI—especially in large-scale and repetitive tasks—due to the high power consumption of data centres.Generative models consume significant amounts of energy and water, so they should only be used when necessary or efficient.AI should be our last resort for querying and information retrieval. Using AI puts a burden on the environment, and its use is often not even necessary.We should use AI judiciously and only when its contribution is needed to protect our planet.

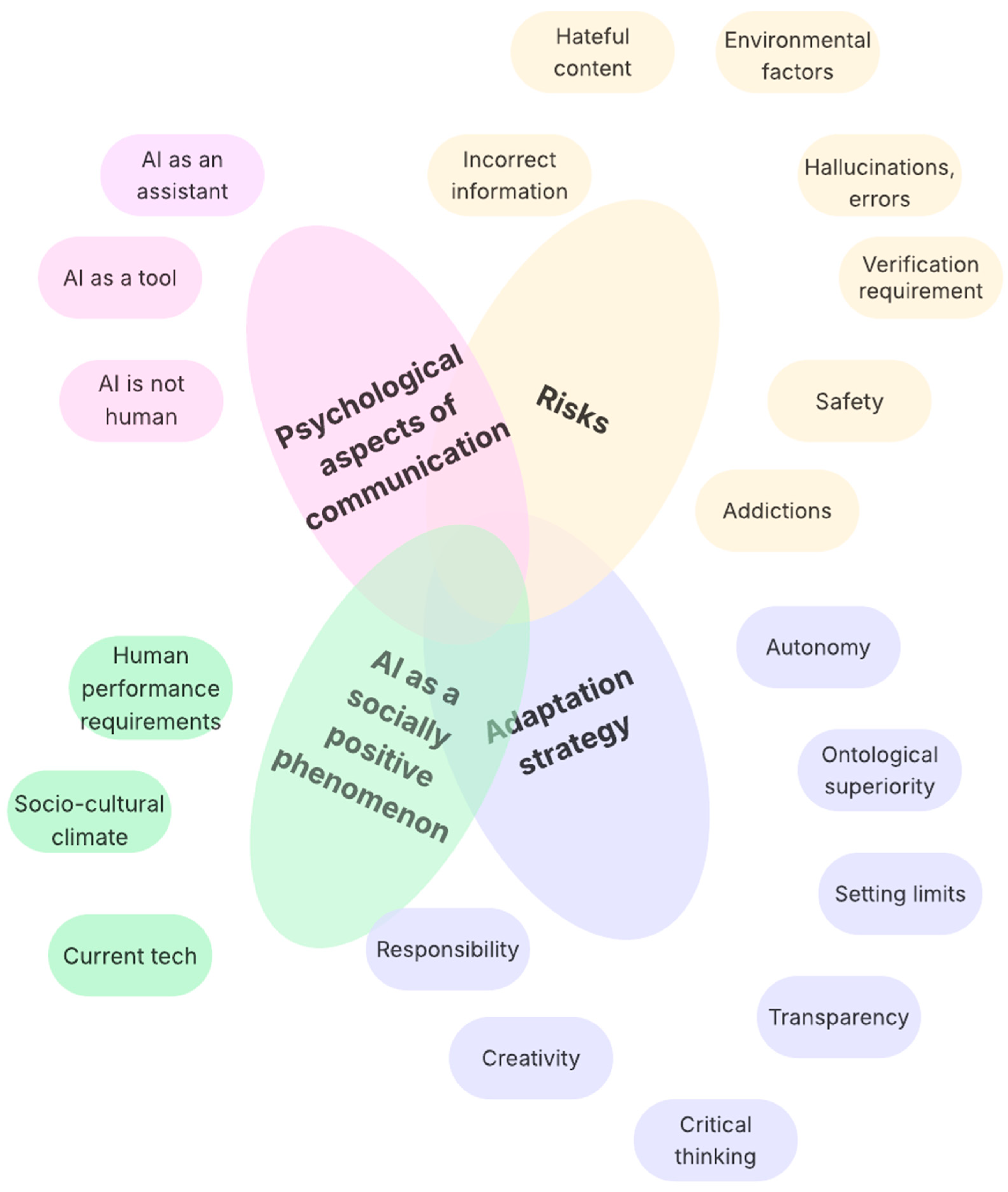

3.4. Dynamic Model of the Relationship Between Digital Wellbeing and AI

4. Discussion

Research Limitations and Ethics

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, M., Madain, A., & Jararweh, Y. (2022, November 29–December 1). ChatGPT: Fundamentals, applications and social impacts. 2022 Ninth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS) (pp. 1–8), Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M., Bani-Melhem, S., Ahmad Al-Hawari, M., & Ahmad, I. (2024). Conversational AI Chatbots in library research: An integrative review and future research agenda. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 52(2), 09610006231224440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Elfa, M. A., & Dawood, M. E. T. (2023). Using artificial intelligence for enhancing human creativity. Journal of Art, Design and Music, 2(2), 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaissi, H., & McFarlane, S. (2023). Artificial hallucinations in ChatGPT: Implications in scientific writing. Cureus, 15(2), e35179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kfairy, M., Mustafa, D., Kshetri, N., Insiew, M., & Alfandi, O. (2024). Ethical challenges and solutions of generative AI: An interdisciplinary perspective. Informatics, 11(3), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naqbi, H., Bahroun, Z., & Ahmed, V. (2024). Enhancing work productivity through generative artificial intelligence: A comprehensive literature review. Sustainability, 16(3), 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, I., Della Greca, A., Francese, R., Tortora, G., & Tucci, C. (2023). AI unreliable answers: A case study on ChatGPT. In H. Degen, & S. Ntoa (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in HCI (pp. 23–40). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L., & De Leo, D. (2022). Human-computer interaction in digital mental health. Informatics, 9(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, A. (2023). A sociological conversation with ChatGPT about AI ethics, affect and reflexivity. Sociology, 57(5), 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. (2013). Liquid modernity. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2022). Introduction to information science (Vol. 2022). Facet Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. (2009). Risk society: Towards a new modernity (repr). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiaridis, G., & Attwell, G. (n.d.). Supplement to the DigCompEDU framework (WP3). AI Pioneers. Available online: https://aipioneers.org/supplement-to-the-digcompedu-framework/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Benko, A., & Sik Lányi, C. (2009). History of artificial intelligence. In D. B. A. Mehdi Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Encyclopedia of information science and technology (2nd ed., pp. 1759–1762). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, R. R., Ennis, E., & Mulvenna, M. D. (2025). How artificial intelligence may affect our mental wellbeing. Behaviour & Information Technology, 44(10), 2093–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In Handbook of research methods in health social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridle, J. (2018). New dark age: Technology and the end of the future. Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, K. M., & Colón-Aguirre, M. (2022). Prepare to be unprepared? LIS curriculum and academic liaison preparation. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(6), 102602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buber, M. (2017). Ich und Du (17. Aufl). Gütersloher Verl.-Haus. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D., & Leung, R. (2018). Smart hospitality—Interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, C., & Floridi, L. (Eds.). (2020a). Ethics of digital well-being: A multidisciplinary approach (Vol. 140). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, C., & Floridi, L. (Eds.). (2020b). The ethics of digital well-being: A multidisciplinary perspective. In Ethics of digital well-being: A multidisciplinary approach (pp. 1–29). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, C., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2020). The ethics of digital well-being: A thematic review. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(4), 2313–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchinato, M. E., Rooksby, J., Hiniker, A., Munson, S., Lukoff, K., Ciolfi, L., Thieme, A., & Harrison, D. (2019, May 4–9). Designing for digital wellbeing: A research & practice agenda. Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–8), Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar, D., Kitto, K., Wu, M., Zhang, Y., Abedin, B., & Knight, S. (2022). Explicating AI literacy of employees at digital workplaces. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K. F. (2023). The impact of Generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: A case of ChatGPT and Midjourney. Interactive Learning Environments, 32, 6187–6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarizia, F., Colace, F., Lombardi, M., Pascale, F., & Santaniello, D. (2018). Chatbot: An education support system for student. In International symposium on cyberspace safety and security (pp. 291–302). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1947–1952). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeckelbergh, M. (2023). Narrative responsibility and artificial intelligence. AI & Society, 38(6), 2437–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condrey, B. J. (2023). The Christian educator as prophet, priest, and king: Nurturing moral formation in a ChatGPT era. International Journal of Christianity & Education, 28(2), 20569971231196809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic books. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. R. (2018). The strange order of things: Life, feeling, and the making of the cultures. Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Damioli, G., Van Roy, V., & Vertesy, D. (2021). The impact of artificial intelligence on labor productivity. Eurasian Business Review, 11(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, K., Tilekya, V., Mamatha, J., & Subetha, T. (2020, August 20–22). Jollity chatbot—A contextual AI assistant. 2020 Third International Conference on Smart Systems and Inventive Technology (ICSSIT) (pp. 1196–1200), Tirunelveli, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Perigee Trade. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J., & Bentley, A. F. (1960). Knowing and the known (Issue 111). Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/251122981/Knowing-and-the-Known-by-Dewey-Bentley (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Dien, J. (2023). Editorial: Generative artificial intelligence as a plagiarism problem. Biological Psychology, 181, 108621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, C. (2011). The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(2), 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D., & Mishra, S. K. (2023). Bots for mental health: The boundaries of human and technology agencies for enabling mental well-being within organizations. Personnel Review, 53(5), 1129–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eager, B., & Brunton, R. (2023). Prompting higher education towards ai-augmented teaching and learning practice. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(5), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, H., & Alija, L. (2023). Comparative analysis of language models: Hallucinations in ChatGPT: Prompt study. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1764165&dswid=-6630 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Ellouze, M., & Hadrich Belguith, L. (2025). Semantic analysis based on ontology and deep learning for a chatbot to assist persons with personality disorders on Twitter. Behaviour & Information Technology, 44(10), 2140–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P., & Rock, D. (2023). GPTs are GPTs: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models. arXiv, arXiv:2303.10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esezoobo, S., & Braimoh, J. (2023). Integrating legal, ethical, and technological strategies to mitigate AI deepfake risks through strategic communication. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 11, 2321–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, F., Tuhuteru, L., Sampe, F., Ausat, A. M. A., & Hatta, H. R. (2023). Analysing the role of ChatGPT in improving student productivity in higher education. Journal on Education, 5(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feerrar, J. (2020). Supporting digital wellness and wellbeing. In Student wellness and academic libraries: Case studies and activities for promoting health and success. ACRL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, F., Bourla, A., Mouchabac, S., & Karila, L. (2018). e-Addictology: An overview of new technologies for assessing and intervening in addictive behaviors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S., Kondja, A., Wong, C. C. K., Weber, K., Moyle, B. D., & Skavronskaya, L. (2024). The role of technology in users’ wellbeing: Conceptualizing digital wellbeing in hospitality and future research directions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 33(5), 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. (2008). Artificial intelligence’s new frontier: Artificial companions and the fourth revolution. Metaphilosophy, 39(4–5), 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. (2013). The philosophy of information. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L. (2014). The fourth revolution: How the infosphere is reshaping human reality. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L. (2023a). AI as agency without intelligence: On ChatGPT, large language models, and other generative models. Philosophy & Technology, 36(1), 15. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L. (2023b). The ethics of artificial intelligence: Principles, challenges, and opportunities. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. (2025). AI as agency without intelligence: On artificial intelligence as a new form of artificial agency and the multiple realisability of agency thesis. Philosophy & Technology, 38(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines, 30, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J. R. (2007). What is intelligence?: Beyond the Flynn effect. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, R., Matera, M., Morra, D., Melonio, A., & Rizvi, M. (2023). Design for social digital well-being with young generations: Engage them and make them reflect. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 173, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldkuhl, G., & Cronholm, S. (2010). Adding theoretical grounding to grounded theory: Toward multi-grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(2), 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S., & Koivisto, M. (2025). Artificial creativity? Evaluating AI against human performance in creative interpretation of visual stimuli. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(7), 4037–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, J., & Sundin, O. (2022). Paradoxes of media and information literacy: The crisis of information. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. (1967a). Being and time. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. (1967b). Die Frage nach der Technik; Wissenschaft und Besinnung; Überwindung der Metaphysik; Wer ist Nietzsches Zarathustra? Neske. [Google Scholar]

- Heston, T. F., & Khun, C. (2023). Prompt engineering in medical education. International Medical Education, 2(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. (2007). The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. (2017). Embodied mind, meaning, and reason. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, B., Çınar, S., & Cenkseven Önder, F. (2025). AI literacy and digital wellbeing: The multiple mediating roles of positive attitudes towards AI and satisfying basic psychological needs. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J., & Lee, J. (2024). The mental health implications of artificial intelligence adoption: The crucial role of self-efficacy. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Kang, Y., Kim, B., Kim, J., & Kim, G. H. (2025). Exploring the role of engagement and adherence in chatbot-based cognitive training for older adults: Memory function and mental health outcomes. Behaviour & Information Technology, 44(10), 2405–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M. R., & ChatGPT. (2023). A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering, 16(1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizhakkethil, P., & Perryman, C. (2024). Are we ready? Generative AI and the LIS curriculum. In Proceedings of the ALISE annual conference. IDEALS University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G. (1990). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. University of Chicago press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought (Nachdr.). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by. The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. (2018). Down to earth: Politics in the new climatic regime (English ed.). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. (2021). After lockdown: A metamorphosis. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W., Chen, H.-C., & Yueh, H.-P. (2021). Using different error handling strategies to facilitate older users’ interaction with chatbots in learning information and communication technologies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 785815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L. (2024). Lévinas’s philosophy of the face: Anxiety, responsibility, and ethical moments that arise in encounters with the other. Human Affairs, 34(3), 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, E., Gröpler, J., & Goudeau, M.-L. S. (2023). Using ChatGPT in education: Human reflection on ChatGPT’s self-reflection. Societies, 13(8), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louati, A., Louati, H., Albanyan, A., Lahyani, R., Kariri, E., & Alabduljabbar, A. (2024). Harnessing machine learning to unveil emotional responses to hateful content on social media. Computers, 13(5), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, N. (2024). ChatGPT: A case study on copyright challenges for generative artificial intelligence systems. European Journal of Risk Regulation, 15(3), 602–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarykova univerzita. (n.d.). Žádost o posouzení—Etická komise pro výzkum. Masarykova univerzita. Available online: https://www.muni.cz/o-univerzite/fakulty-a-pracoviste/rady-a-komise/eticka-komise-pro-vyzkum/zadost-o-posouzeni (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Montag, C., Yang, H., Wu, A. M. S., Ali, R., & Elhai, J. D. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in general, and large language models specifically, for understanding addictive behaviors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1548(1), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moşteanu, N. R. (2020). Green sustainable regional development and digital era. In A. Sayigh (Ed.), Green buildings and renewable energy: Med green forum 2019—Part of world renewable energy congress and network (pp. 181–197). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. R. (2017). Capturing student learning with thematic analysis. Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(6), 342–347. Available online: https://jarssh.com/ojs/index.php/jarssh/article/view/129 (accessed on 20 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nabor, Z. B., Onesa, R. O., Pandes, T. L. O., & Oñate, J. J. S. (2024, September 30–October 2). Thematic analysis of students’ perception and attitudes towards online class using latent dirichlet allocation. 2024 Artificial Intelligence x Humanities, Education, and Art (AIxHEART) (pp. 64–69), Laguna Hills, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D. T. K., Luo, W., Chan, H. M. Y., & Chu, S. K. W. (2022). Using digital story writing as a pedagogy to develop AI literacy among primary students. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M. H. (2021). Managing social media use in an “always-on” society: Exploring digital wellbeing strategies that people Use to disconnect. Mass Communication and Society, 24(6), 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M. H., & Hargittai, E. (2024). Digital disconnection, digital inequality, and subjective well-being: A mobile experience sampling study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(1), zmad044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. (2001). Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, D. A., Le Roux, D. B., Morton, J., Pons, R., Pretorius, R., & Schoeman, A. (2023). Digital wellbeing applications: Adoption, use and perceived effects. Computers in Human Behavior, 139, 107542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, R., Vadapalli, R., & Mader, C. (2023, November 21–24). Cyber security issues and challenges related to generative AI and ChatGPT. 2023 Tenth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS) (pp. 1–5), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D., & Ahmadpour, N. (2021, December 2–4). Digital wellbeing through design: Evaluation of a professional development workshop on wellbeing-supportive design. 32nd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 148–157), Sydney, NSW, Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöhler, J., Flegel, N., Mentler, T., & Laerhoven, K. V. (2025). Keeping the human in the loop: Are autonomous decisions inevitable? I-Com, 24(1), 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punie, Y. (2017). European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu. European Commission. Joint Research Centre. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffarello, A. M., & De Russis, L. (2019, May 4–9). The race towards digital wellbeing: Issues and opportunities. The 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–14), Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rude, T. A., & Frenzel, J. E. (2022). Cooperative wikis used to promote constructivism and collaboration in a skills laboratory course. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 14(10), 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J., Tan, S., & Tan, S. (2023). War of the chatbots: Bard, Bing Chat, ChatGPT, Ernie and beyond. The new AI gold rush and its impact on higher education. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 364–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanji, M., Behzadi, H., & Gomroki, G. (2022). Chatbot: An intelligent tool for libraries. Library Hi Tech News, 39(3), 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni de Sio, F., & Mecacci, G. (2021). Four responsibility gaps with artificial intelligence: Why they matter and how to address them. Philosophy & Technology, 34(4), 1057–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, R. (2022). Passing the turing test? AI generated poetry and posthuman creativity. In Artificial intelligence and human enhancement: Affirmative and critical approaches in the humanities (Vol. 2022, pp. 151–166). De Gruyter Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being (1. Free Press hardcover ed). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y., Wu, J., Xu, W., & Zhang, C. (2024). The impact of digital technology use on adolescents’ subjective well-being: The serial mediating role of flow and learning engagement. Medicine, 103(43), e40123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M., & Kaur, M. (2022). A review of deepfake technology: An emerging AI threat. In G. Ranganathan, X. Fernando, F. Shi, & Y. El Allioui (Eds.), Soft computing for security applications (pp. 605–619). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, J. M., & Ma, S. (2019). Inquiry and critical thinking skills for the next generation: From artificial intelligence back to human intelligence. Smart Learning Environments, 6(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šíp, R. (2019). Proč školství a jeho aktéři selhávají. Masarykova univerzita. [Google Scholar]

- Theophilou, E., Koyutürk, C., Yavari, M., Bursic, S., Donabauer, G., Telari, A., Testa, A., Boiano, R., Hernandez-Leo, D., Ruskov, M., Taibi, D., Gabbiadini, A., & Ognibene, D. (2023). Learning to prompt in the classroom to understand AI limits: A pilot study. In R. Basili, D. Lembo, C. Limongelli, & A. Orlandini (Eds.), AIxIA 2023—Advances in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 481–496). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trocin, C., Mikalef, P., Papamitsiou, Z., & Conboy, K. (2023). Responsible AI for digital health: A synthesis and a research agenda. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(6), 2139–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. (2021). Digital wellbeing as a dynamic construct. Communication Theory, 31(4), 932–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maden, W., Lomas, D., Sadek, M., & Hekkert, P. (2024). Positive AI: Key challenges in designing artificial intelligence for wellbeing. arXiv, arXiv:2304.12241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, J. (2020). Governing digital societies: Private platforms, public values. Computer Law & Security Review, 36, 105377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, J., & Lin, J. (2022). Deplatformization, platform governance and global geopolitics: Interview with José van Dijck. Communication and the Public, 7(2), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J., & Hacker, K. (2003). The digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon. The Information Society, 19(4), 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virós-Martín, C., Montaña-Blasco, M., & Jiménez-Morales, M. (2024). Can’t stop scrolling! Adolescents’ patterns of TikTok use and digital well-being self-perception. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waight, S., & Holley, D. (2020). Digital competence frameworks: Their role in enhancing digital wellbeing in nursing curricula. In Humanising higher education (Vol. 2020, pp. 125–143). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D., & Myrick, F. (2006). Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, J. (2021). Artificial intelligence and the value of transparency. AI & Society, 36(2), 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M. (2019). The impact of artificial intelligence on the labor market. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, F. (2014). Theories of the information society. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- West, M. (2023). An ed-tech tragedy? Educational technologies and school closures in the time of COVID-19. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyk, B. V. (2024). Exploring the philosophy and practice of AI literacy in higher education in the Global South: A scoping review. Cybrarians Journal, 73, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifhonarvar, A. (2023). Economics of ChatGPT: A labor market view on the occupational impact of artificial intelligence. Journal of Electronic Business & Digital Economics, 3(2), 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewe, A. (2025, January 17). Explained: Generative AI’s environmental impact. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2025/explained-generative-ai-environmental-impact-0117 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Zlotnikova, I., Hlomani, H., Mokgetse, T., & Bagai, K. (2025). Establishing ethical standards for GenAI in university education: A roadmap for academic integrity and fairness. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 23(2), 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Description | Frequency | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI literacy | Topics related to understanding the principles of how AI works, how to use it effectively, and learning how to work with AI. | 60 | Effectiveness and prompting (20), AI principles (17), education (17), and miscellaneous (8). |

| Copyright | Topics related to copyright protection and copyright abuse by AI tools. | 17 | |

| Security—general | General security features that could not be classified as data and information protection. This includes, for example, the choice of passwords for services. | 9 | |

| Uncategorized | Statements that could not be classified in any of the categories | 10 | |

| Environmental factors | Statements related to limitations on using AI concerning ecological and environmental factors. | 44 | |

| Ethics | Rules relating to various aspects of ethical work with generative AI—on transparency and explication of use, plagiarism, creation of false, hateful or mendacious content, and other elements. | 75 | Hateful and false content (24), plagiarism (8), transparency (24), and miscellaneous (23) |

| Thinking | Statements related to transforming thinking, especially creativity, critical thinking, the limits of AI, themes of accountability, and understanding AI as a facilitator | 91 | AI as an enabler (13), creativity (6), critical thinking (30), limits of AI (19), responsibility (17), miscellaneous (6). |

| Data and information protection | Data and information protection rules, especially at the input level (not giving out personal data of oneself or others, passwords, etc.). | 49 | |

| Verification of information | Topics related to the need to verify information obtained because of its low or questionable reliability. | 47 | |

| Wellbeing | Topics related to wellbeing itself, mainly referring to the need to set time and other limits, that AI is not human, and AI must have other kinds of interactions, but also other specific measures | 72 | Time and boundaries (39), inhuman actors (17), other specific measures—outside of time (8), and miscellaneous (12) |

| AI Literacy | Copyright | Data and Information Protection | Environmental Factors | Ethics | Security—General | Thinking | Uncategorized | Verification of Information | Wellbeing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI literacy | X | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Copyright | X | |||||||||||

| Data and information protection | X | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Environmental factors | X | |||||||||||

| Ethics | X | 4 | ||||||||||

| Security—general | 2 | 1 | X | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Thinking | 6 | 4 | 1 | X | 1 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| Uncategorized | 3 | 1 | X | |||||||||

| Verification of information | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | X | 1 | ||||||

| Wellbeing | 1 | 8 | 1 | X | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Černý, M. Conceptualisation of Digital Wellbeing Associated with Generative Artificial Intelligence from the Perspective of University Students. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100197

Černý M. Conceptualisation of Digital Wellbeing Associated with Generative Artificial Intelligence from the Perspective of University Students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(10):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100197

Chicago/Turabian StyleČerný, Michal. 2025. "Conceptualisation of Digital Wellbeing Associated with Generative Artificial Intelligence from the Perspective of University Students" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 10: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100197

APA StyleČerný, M. (2025). Conceptualisation of Digital Wellbeing Associated with Generative Artificial Intelligence from the Perspective of University Students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(10), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100197