Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence and Child-to-Parent Violence: Bidirectional Trajectories and Associated Longitudinal Risk Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence: A New Form of Child-to-Parent Violence

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Ethical Aspects

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence

2.3.2. Child-to-Parent Violence

2.3.3. Distress

2.3.4. Exposure to Family Violence

2.3.5. Punitive Discipline

2.3.6. Parental Ineffectiveness and Parental Impulsivity

2.3.7. Substance Abuse

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

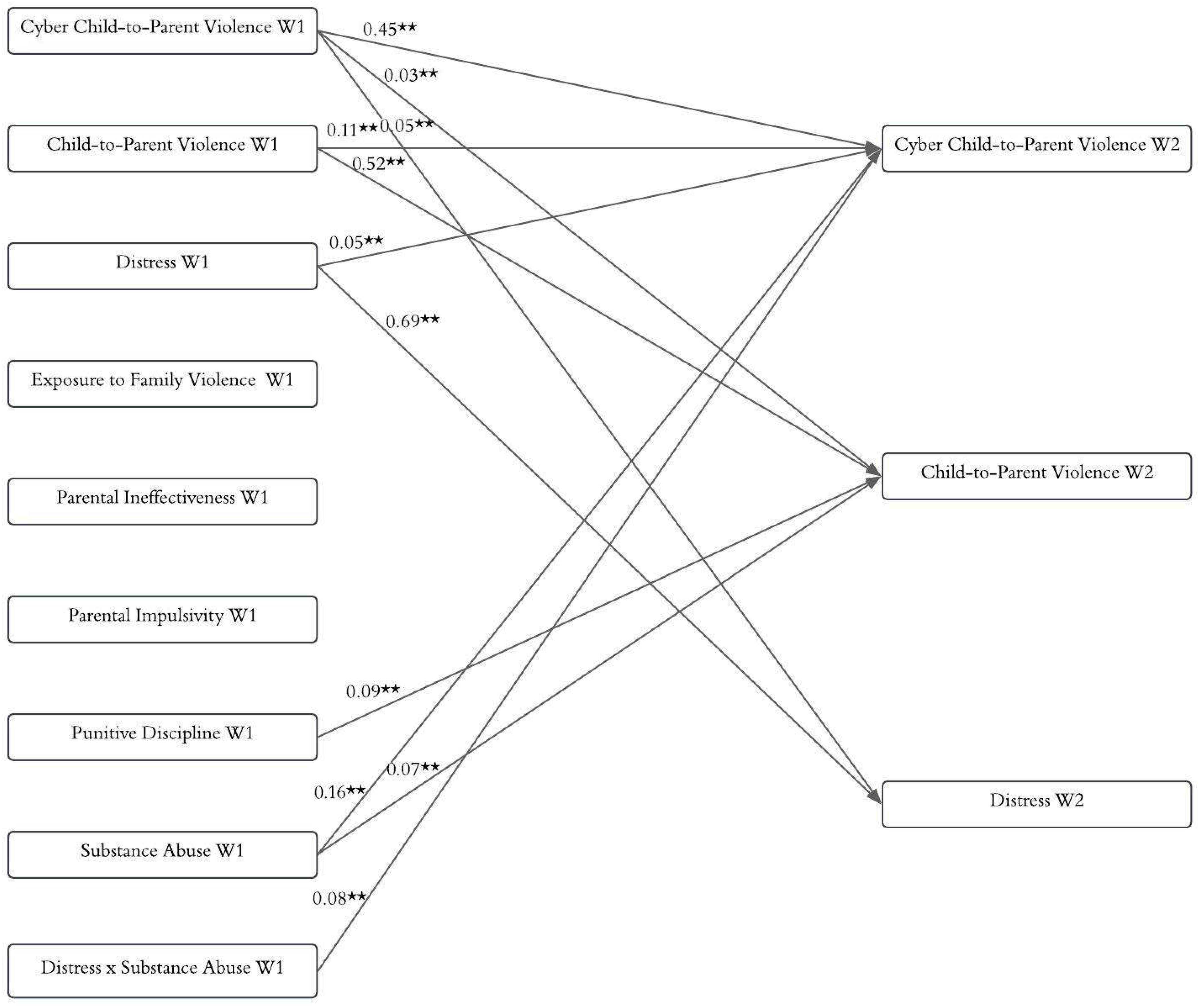

3.2. Predictive Model

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Strengths and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armstrong, G. S., Cain, C. M., Wylie, L. E., Muftić, L. R., & Bouffard, L. A. (2018). Risk factor profile of youth incarcerated for child to parent violence: A nationally representative sample. Journal of Criminal Justice, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G. S., Muftić, L. R., & Bouffard, L. A. (2021). Factors influencing law enforcement responses to child to parent violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), NP4979–NP4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, L., Bergamann, M. C., Fischer, F., & Mößle, T. (2021). Risk and protective factors of child-to-parent violence: A comparison between physical and verbal aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1309–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehal, N. (2012). Parent abuse by young people on the edge of care: A child welfare perspective. Social Policy and Society, 11(2), 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, E., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2015). Cyber dating abuse: Prevalence, context, and relationship with offline dating aggression. Psychological Reports: Relationships & Communications, 116(2), 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2010). Aggression. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 833–863). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, E., & Estévez, A. (2009). Substance abuse in adolescents: The role of stress, impulsivity, and schemas related to lack of boundaries. Addictions, 21(1), 49–56. Available online: https://www.adicciones.es/index.php/adicciones/article/view/251 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Calvete, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., & Orue, I. (2010). The dimensions of discipline inventory (DDI)-child and adolescent version: Analysis of the parental discipline from a gender perspective. Anales De Psicología, 26(2), 410–418. Available online: http://revistas.um.es/analesps (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Calvete, E., Jiménez-Granado, A., & Orue, I. (2023). The revised child-to-parent aggressions questionnaire: An examination during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 38(8), 1563–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., Fernández-González, L., Chang, R., & Little, T. D. (2020). Longitudinal trajectories of child-to-parent violence through adolescence. Journal of Family Violence, 35(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2012). Child-to-parent violence: Emotional and behavioral predictors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., & González-Cabrera, J. (2017). Child-to-parent violence: Comparing reports from adolescents and their parents. Journal of Clinical Psychology with Children and Adolescents, 4(1), 9–15. Available online: https://www.revistapcna.com/sites/default/files/16-08.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Sampedro, R. (2011). Child-to-parent violence in adolescence: Environmental and personal characteristics. Childhood and Learning, 34(3), 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A., Runions, K., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Romera, E. M. (2023). Bullying and cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: Prospective with-person associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(2), 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lozano, M. C., León, S. P., & Contreras, L. (2021). Relationship between punitive discipline and child-to-parent violence: The moderating role of the context and implementation of parenting practices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lozano, M. C., Navas-Martínez, M. J., & Contreras, L. (2024). Lagged and simultaneous effects of exposure to violence at home on child-to-parent violence: Gender differences. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1441871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridade, S. M. M., & Braga, T. (2020). Youth cyber dating abuse: A meta-analysis of risk and protective factors. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(3), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M. J., Buelga, S., Carrascosa, L., & Ortega-Barón, J. (2020). Relations among romantic myths, offline dating violence victimization and cyber dating violence victimization in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, L., & Cano, M. C. (2015). Exploring psychological features in adolescents who assault their parents: A different profile of young offenders? The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 26(2), 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, L., & Cano-Lozano, M. C. (2014). Family profile of young offenders who abuse their parents: A comparison with general offenders and non-offenders. Journal of Family Violence, 29(8), 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, H., & Martín, A. M. (2020). The behavioral specificity of child-to-parent violence. Annals of Psychology, 36(3), 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, K. (2025). Risk factor profile in child-to-parent violence: A gender analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 52(4), 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahouri, A., Mirghafourvand, M., Zahedi, H., Maghalian, M., & Hosseinzadeh, M. (2025). Prevalence of child to parent violence and its determinants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 25, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J. F. (2018). Interpreting interaction effects. Available online: http://www.jeremydawson.com/slopes.htm (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., Gámez-Guadix, M., & Calvete, E. (2018). Corporal punishment by parents and child-to-parent aggression in Spanish adolescents. Annals of Psychology, 34, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., Orue, I., Gámez-Guadix, M., & Calvete, E. (2020). Multivariate models of child-to-mother violence and child-to-father violence among adolescents. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 12(1), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Amigó. (2025). Child-to-parent violence in Spain. Available online: https://fundacionamigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/vfp2024.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Guidi, S., Palmitesta, P., Bracci, M., Marchigiani, E., Di Pomponio, I., & Parlangeli, O. (2022). How many cyberbullying(s)? A non-unitary perspective for offensive online behaviours. PLoS ONE, 17(7), e0268838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, A. (2022). Child to parent abuse. HM Inspectorate of Probation. Available online: https://pure.roehampton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/8676690/Academic_Insights_Child_to_Parent_Abuse_Dr_Amanda_Holt.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Ibabe, I. (2019). Adolescent-to-parent violence and family environment: The perceptions of same reality? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I. (2020). A systematic review of youth-to-parent aggression: Conceptualization, typologies, and instruments. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 577757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibabe, I., Arnoso, A., & Elgorriaga, E. (2014). Behavioral problems and depressive symptomatology as predictors of child-to-parent violence. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 6(2), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, A., & Calvete, E. (2017). Exposure to family violence as a predictor of dating violence and child-to-parent aggression in Spanish adolescents. Youth & Society, 49(3), 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregizar, J., Dosil-Santamaria, M., Redondo, I., Wasch, S., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2024). Online and offline dating violence: Same same, but different? Psicologia: Reexão E Crítica, 37, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Granado, A., del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., & Fernández-González, L. (2023a). Interaction of parental discipline strategies and adolescents’ personality traits in the prediction of child-to-parent violence. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 15(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Granado, A., Fernández-González, L., & del Hoyo-Bilbao, J. (2025). Longitudinal reciprocal associations between internalizing symptoms and child-to-parent violence in adolescents: The role of cognitive mechanisms. Psychology of Violence, 15(5), 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Granado, A., Fernández-González, L., del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., & Calvete, E. (2023b). Psychological symptoms in parents who experience child-to-parent violence: The role of self-efficacy beliefs. Healthcare, 11(21), 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (2006). LISREL 8.80 for windows [Computer software]. Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Junco-Guerrero, M., Fernández-Baena, F. J., & Cantón-Cortés, D. (2025). Risk factors for child-to-parent violence: A scoping review. Journal of Family Violence, 40(1), 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F., Limbana, T., Zahid, T., Eskander, N., & Jahan, N. (2020). Traits, trends, and trajectory of tween and teen cyberbullies. Curēus, 12(8), e9738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Harris, M., & Kim, J. (2022). Gender differences in cyberbullying victimization from a developmental perspective: An examination of risk and protective factors. Crime and Delinquency, 68(13–14), 2422–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Ran, G., Zhang, Q., & He, X. (2023). The prevalence of cyber dating abuse among adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 144, 107726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, B., Caridade, S., Araújo, I., & Lobato-Faria, P. (2022). Mapping the cyber interpersonal violence among young populations: A scoping review. Social Sciences, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marganski, A., & Melander, L. (2018). Intimate partner violence victimization in the cyber and real world: Examining the extent of cyber aggression experiences and its association with in-person dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(7), 1071–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ferrer, B., Romero-Abrio, A., León-Moreno, C., Villarreal-González, M. E., & Musitu-Ferrer, D. (2020). Suicidal ideation, psychological distress and child-to-parent violence: A gender analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, F. J. (1951). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 46(253), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Fernández, N., & Sánchez-Jiménez, V. (2020). Cyber-aggression and psychological aggression in adolescent couples: A short-term longitudinal study on prevalence and common and differential predictors. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orue, I., & Calvete, E. (2010). Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure exposure to violence in childhood and adolescence. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 10(2), 279–292. Available online: https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen10/num2/262.html (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Park, S., & Kim, Y. (2016). Prevalence, correlates, and associated psychological problems of substance use in Korean adolescents. BMC Public Health, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechorro, P., DeLisi, M., Freitas, A., Abrunhosa Gonzçalvez, R., & Nunes, C. (2023). Examination of the Weinberger adjustment inventory–short form among Portuguese young adults: Psychometrics and measurement invariance. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 67(8), 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R., & Bertino, L. (2009). An ecological understanding of child-to-parent violence. Journal of Relational Psychotherapy and Social Interventions, 21, 69–90. Available online: https://www.robertopereiratercero.es/articulos/Una_compr_ecol%C3%B3g_de_la_VFP.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Pereira, R., Loinaz, I., Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., Arospide, J., Bertino, L., Calvo, A., Montes, Y., & Guiterrez, M. M. (2017). Proposal for a definition of filio-parental violence: Consensus of the Spanish society for the study of filio-parental violence (SEVIFIP). Papeles Del Psicólogo, 38(3), 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, S., Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., & Echezarraga, A. (n.d.-a). Cyber child-to-parent violence: A qualitative study from the perspective of adolescents, parental figures and professionals. Unpublished manuscript submitted for publication.

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, S., Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., Echezarraga, A., & Fernández-González, L. (n.d.-b). Cyber child-to-parent violence: Assessment and prevalence according to adolescents’ and parent’s reports. Unpublished manuscript submitted for publication.

- Rogers, M. M., & Ashworth, C. (2024). Child-to-parent violence and abuse: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(4), 3285–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, A., Junco-Guerrero, M., & Cantón-Cortés, D. (2021). Exploring the mediating effect of psychological engagement on the relationship between child-to-parent violence and violent video games. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoffstall, C. L., & Cohen, R. (2011). Cyber aggression: The relation between online offenders and offline social competence. Social Development, 20(3), 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schokkenbroek, J. M., Van Ouytsel, J., Hardyns, W., & Ponnet, K. (2022). Adults’ online and offline psychological intimate partner violence experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15–16), NP14656–NP14671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M., McEwan, T. E., Purcell, R., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2018). Sixty years of child-to-parent abuse research: What we know and where to go. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, K. (2020). “Technology was designed for this”: Adolescents’ perceptions of the role and impact of the use of technology in cyber dating violence. Computers in Human Behavior, 105, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M. A., & Fauchier, A. (2007). Manual for the dimensions of discipline inventory (DDI). Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Relinque, C., & Del Moral-Arroyo, G. (2023). Child-to-parent cyber violence: What is the next step? Journal of Family Violence, 38(2), 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S., Zhang, T., Chen, X., & Pan, C.-W. (2021). Substance abuse and psychological distress among school-going adolescents in 41 low-income and middle-income countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, D. S., van der Ven, E., Velthorst, E., Selten, J. P., Morgan, C., & de Haan, L. (2012). Childhood bullying and the association with psychosis in non-clinical and clinical samples: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 42, 2463–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Systematic review of theoretical studies on bullying and cyberbullying: Facts, knowledge, prevention and intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence W1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence W2 | 0.58 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Child-to-Parent Violence W1 | 0.48 ** | 36 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. Child-to-Parent Violence W2 | 0.37 ** | 49 ** | 0.59 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 5. Distress W1 | 0.24 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.24 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 6. Distress W2 | 0.22 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.70 ** | 1 | |||||

| 7. Exposure to Family Violence W1 | 0.37 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.31 ** | 1 | ||||

| 8. Parental Ineffectiveness W1 | 0.32 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.31 ** | 1 | |||

| 9. Parental Impulsiveness W1 | 0.21 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.10 * | 0.32 ** | 0.36 ** | 1 | ||

| 10. Punitive Discipline W1 | 0.48 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.39 ** | 1 | |

| 11. Substance Abuse W1 | 0.29 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.14 * | 0.10 * | 0.24 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez-Gonzalez, S.; Echezarraga, A.; Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J. Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence and Child-to-Parent Violence: Bidirectional Trajectories and Associated Longitudinal Risk Factors. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100190

Rodriguez-Gonzalez S, Echezarraga A, Del Hoyo-Bilbao J. Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence and Child-to-Parent Violence: Bidirectional Trajectories and Associated Longitudinal Risk Factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(10):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100190

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez-Gonzalez, Sara, Ainara Echezarraga, and Joana Del Hoyo-Bilbao. 2025. "Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence and Child-to-Parent Violence: Bidirectional Trajectories and Associated Longitudinal Risk Factors" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 10: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100190

APA StyleRodriguez-Gonzalez, S., Echezarraga, A., & Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J. (2025). Cyber Child-to-Parent Violence and Child-to-Parent Violence: Bidirectional Trajectories and Associated Longitudinal Risk Factors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(10), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15100190