The Mediating Role of School Refusal in the Relationship Between Students’ Perceived School Atmosphere and Underachievement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. School Refusal and Underachievement

1.2. School Refusal and School Atmosphere

1.3. School Refusal and School Engagement

1.4. Relationship Between School Atmosphere, School Refusal, and Success

2. The Present Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Correlation

4.2. Mediation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, C. M., Ware, J. K., Miskell, R. C., & Forsyth, P. B. (2016). Self-regulatory climate: A positive attribute of public schools. Journal of Educational Research, 109(2), 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, V. R., & Kearney, C. A. (2020). School climate and student-based contextual learning factors as predictors of school absenteeism severity at multiple levels via CHAID analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Edwards, J. R. (1998). A general approach to representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 1, 45–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C., Fraccaroli, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, D. (2020). Truancy begins in class: Student perspectives of tenuous peer relationships. Pastoral Care in Education, 39, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L., Liu, P., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Shambaugh, J. (2018). Reducing chronic absenteeism under the every student succeeds act (pp. 1–31). Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., Roziner, I., & Wrabel, S. L. (2016). Testing the causal links between school climate, school violence, and school academic performance: A cross-lagged panel autoregressive model. Educational Researcher, 45(3), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouda, N. E., Elafri, M., Hamel, A., Nabti, F., & Gana, K. (2024). Assessing school refusal: Arabic adaptation and psychometric properties of the school refusal evaluation (SCREEN) from adolescents in Algeria. School Mental Health, 16(1), 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer-Borghuis, M., Heyne, D., Sauter, F., & Scholte, R. (2019). The link: An alternative educational program in the netherlands to re-engage school-refusing adolescents with schooling. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzai, C., Filippello, P., Costa, S., Amato, V., & Sorrenti, L. (2021a). Problematic internet use and academic achievement: A focus on interpersonal behaviours and academic engagement. Social Psychology of Education, 24, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzai, C., Sorrenti, L., Tripiciano, F., Orecchio, S., & Filippello, P. (2021b). School alienation and academic achievement: The role of learned helplessness and mastery orientation. School Psychology, 36(1), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchele, S. (2021). Evaluating the link between attendance and performance in higher education: The role of classroom engagement dimensions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(1), 132–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chere, N. E., & Hlalele, D. (2014). Academic underachievement of learners at school: A literature review. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(23), 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chory-Assad, R. M. (2002). Classroom justice: Perceptions of fairness as a predictor of student motivation, learning, and aggression. Communication Quarterly, 50(1), 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, D. F. (2002). Aggression and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: Research and treatment. The Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, D., González, L., Láscar, S., & López, V. (2022). Negative teacher–student and student–student relationships are associated with school dropout: Evidence from a large-scale longitudinal study in Chile. International Journal of Educational Development, 91, 102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, S. M., Smith, M. L., Lilly, C. L., Davidov, D. M., Mann, M. J., & Kristjansson, A. L. (2020). Using school climate to improve attendance and grades: Understanding the importance of school satisfaction among middle and high school students. Journal of School Health, 90(9), 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donat, M., Gallschütz, & Dalbert, C. (2018). The relation between students’ justice experiences and their school refusal behavior. Social Psychology of Education, 21, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Narucki, V. (2008). School building condition, school attendance, and academic achievement in New York City public schools: A mediation model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(3), 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, R. E., & Connolly, F. (2017). Strategies for student attendance and school climate in Baltimore’s community schools. Baltimore Education Research Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Finning, K., Harvey, K., Moore, D., Ford, T., Davis, B., & Waite, P. (2018). Secondary school educational practitioners’ experiences of school attendance problems and interventions to address them: A qualitative study. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 23(2), 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, L., Marcotte, D., Potvin, P., Royer, E., & Joly, J. (2006). Typology of student at risk of dropping out of school: Description by personal, family and school factors. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(4), 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 763–782). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., McCoach, D. B., Sugai, G., Lombardi, A., & Horner, R. (2016). Relationship between school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports and academic, attendance, and behavior outcomes in high schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallé-Tessonneau, M., & Gana, K. (2019). Development and validation of the school refusal evaluation scale for adolescents. Journal of pediatric psychology, 44(2), 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallé-Tessonneau, M., & Heyne, D. (2020). Behind the SCREEN: Identifying school refusal themes and sub-themes. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 25(2), 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenson, S. (2016). Linking teacher quality, student attendance, and student achievement. Education Finance and Policy, 11(2), 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen-O’Neel, C. (2021). Sense of belonging and student engagement: A daily study of first-and continuing-generation college students. Research in Higher Education, 62(1), 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesser, D., Holl, C., Malinka, J., McCullagh, L., Meissner, L., Harth, N. S., Machunsky, M., & Mitte, K. (2024). Examining the association between social context and disengagement: Individual and classroom factors in two samples of at-risk students. Social Psychology of Education, 27(1), 115–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzálvez, C., Kearney, C. A., Vicent, M., & Sanmartín, R. (2021). Assessing school attendance problems: A critical systematic review of questionnaires. International journal of educational research, 105, 101702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazia, V., & Molinari, L. (2021). School climate research: Italian adaptation and validation of a multidimensional school climate questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 39(3), 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazia, V., Molinari, L., & Mameli, C. (2024). Contrasting school dropout: The protective role of perceived teacher justice. Learning and Instruction, 89, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J., van der Put, C. E., & Assink, M. (2019). Risk factors for school absenteeism and dropout: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, D. (2021). Can a positive school climate promote student attendance? Evidence from New York City. American Educational Research Journal, 58(2), 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. N., & Sass, T. R. (2011). Teacher training, teacher quality and student achievement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, K. T., & Marsh, H. W. (2004). The use of item parcels in structural equation modelling: Nonnomral data and small sample sizes. The British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology, 57, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havik, T., & Westergård, E. (2020). Do teachers matter? Students’ perceptions of classroom interactions and student engagement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(4), 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2015). School factors associated with school refusal and truancy-related reasons for school non-attendance. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, J., Schneider, F., Lahoud, N., Tueni, M., & de Vries, H. (2022). Authoritative parenting stimulates academic achievement, also partly via self-efficacy and intention towards getting good grades. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0265595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendron, M., & Kearney, C. A. (2016). School climate and student absenteeism and internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems. Children and Schools, 38, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D., Saldanha, N., & Deng, X. (2007). A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingul, J. M., Havik, T., & Heyne, D. (2019). Emerging school refusal: A school-based framework for identifying early signs and risk factors. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(1), 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapri, U. (2017). A study of underachievement in science in relation to permissive school environment. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 4(7), 2027–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Karlberg, M., Klang, N., Andersson, F., Hancock, K., Ferrer-Wreder, L., Kearney, C., & Galanti, M. R. (2022). The importance of school pedagogical and social climate to students’ unauthorized absenteeism a multilevel study of 101 Swedish schools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(1), 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, C. A., Childs, J., & Burke, S. (2023). Social forces, social justice, and school attendance problems in youth. Contemporary School Psychology, 27(1), 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppens, G., & Spruyt, B. (2019). The school as a socialization context: Understanding the influence of school bonding and an authoritative school climate on class skipping. Youth & Society, 51(8), 1145–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khursheed, F., Inam, A., & Abiodullah, M. (2021). Development and validation of a scale to assess the factors contributing towards school refusal behavior. Pakistan Journal of Education, 38(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Gentle-Genitty, C. (2020). Transformative school–community collaboration as a positive school climate to prevent school absenteeism. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(8), 2678–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishton, J. M., & Widaman, K. F. (1994). Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Konold, T., Cornell, D., Jia, Y., & Malone, M. (2018). Relational climate, student engagement, and academic achievement: A latent variable, multilevel multi-informant examination. School Psychology Quarterly, 33, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotok, S., Ikoma, S., & Bodovski, K. (2016). School climate and dropping out of school in the era of accountability. American Journal of Education, 122(4), 569–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, A., Butler-Kisber, L., Fortin, L., Marcotte, D., Potvin, P., & Royer, E. (2008). Shades of disengagement: High school dropouts speak out. Social Psychology of Education, 11, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency & substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, M. (2008). Item parceling in structural equation modeling: A primer. Communication Methods and Measures, 2(4), 260–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L., & Grazia, V. (2023). A multi-informant study of school climate: Student, parent, and teacher perceptions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38, 1403–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brennan, L., & Bradshaw, C. (2013). Importance of school climate. National Education Association Research Bried. [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas, P., & Raczynski, K. (2016). School climate associated with school dropout among tenth graders. Pensamiento Psicológico, 14(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2020). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 21(1), 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, D., & Miles, S. (2022). A caring climate that promotes belonging and engagement. Phi Delta Kappan, 103(5), 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, D., & Khanal, Y. K. (2017). Emotional intelligence and emotional maturity and their relationship with academic achievement of college students in Sikkim. International Journal of Education and Psychological Research, 6(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Railsback, J. (2004). Increasing student attendance: Strategies from research and practice. Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory NWREL. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzotto, J. S., & França, M. T. A. (2022). Indiscipline: The school climate of Brazilian schools and the impact on student performance. International Journal of Educational Development, 94, 102657. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K. M., Snyder, K. E., Levincon, H., & Adelson, J. L. (2018). Systems view of school climate: A theoretical framework for research. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. (2004). Job demands, job resources and their relationship with burnout end engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, E., Hwang, S. A., Fitzgerald, E. F., Kielb, C., & Lin, S. (2010). The impact of school building conditions on student absenteeism in upstate New York. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, K. E., Carrig, M. M., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2021). Developmental pathways in underachievement. Applied Developmental Science, 25(2), 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H. L., Mcdougall, P., & Duku, E. (2013). Longitudinal links between childhood peer victimization, internalizing and externalizing problems, and academic functioning: Developmental cascades. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1203–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, K., Johnson, S. R., Bettencourt, A., & Johnson, S. L. (2017). How school climate relates to chronic absence: A multi-level latent profile analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 61, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, T., Pelkonen, J., & Kiuru, N. (2023). Reciprocal relationships between perceived supportive school climate and self-reported truancy: A longitudinal study from grade 6 to grade 9. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(4), 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J., Ye, F., Hofkens, T., & Linn, J. S. (2019). Conceptualization and assessment of adolescents’ engagement and disengagement in school: A multidimensional school engagement scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., & Jia, F. (2013). A new procedure to test mediation with missing data through nonparametric bootstrapping and multiple imputation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 48(5), 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., & Patton, J. M. (2011). Relationships among school climate domains and school satisfaction. Psychology in the Schools, 48(2), 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxious Anticipation | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Difficult Transition | 0.56 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Interpersonal Discomfort | 0.52 | *** | 0.25 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 4. School Avoidance | 0.49 | *** | 0.36 | *** | 0.19 | *** | — | |||||||||||||

| 5. School Engagement | −0.33 | *** | −0.54 | *** | −0.18 | *** | −0.16 | *** | — | |||||||||||

| 6. Educational Climate | 0.19 | *** | 0.20 | *** | 0.19 | *** | 0.13 | ** | −0.15 | *** | — | |||||||||

| 7. Student–Teacher Relations | 0.21 | *** | 0.27 | *** | 0.13 | ** | 0.10 | * | −0.20 | *** | 0.57 | *** | — | |||||||

| 8. Student Relations | 0.11 | * | 0.23 | *** | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.18 | *** | 0.56 | *** | 0.54 | *** | — | |||||||

| 9. Sense of Belonging | 0.27 | *** | 0.29 | *** | 0.24 | *** | 0.12 | ** | −0.25 | *** | 0.55 | *** | 0.53 | *** | 0.64 | *** | — | |||

| 10. Interpersonal Justice | 0.16 | *** | 0.22 | *** | 0.04 | 0.11 | * | −0.25 | *** | 0.44 | *** | 0.53 | *** | 0.55 | *** | 0.52 | *** | — | ||

| 11. Underachievement | 0.17 | *** | 0.14 | ** | 0.01 | 0.39 | *** | −0.09 | * | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | ||||||

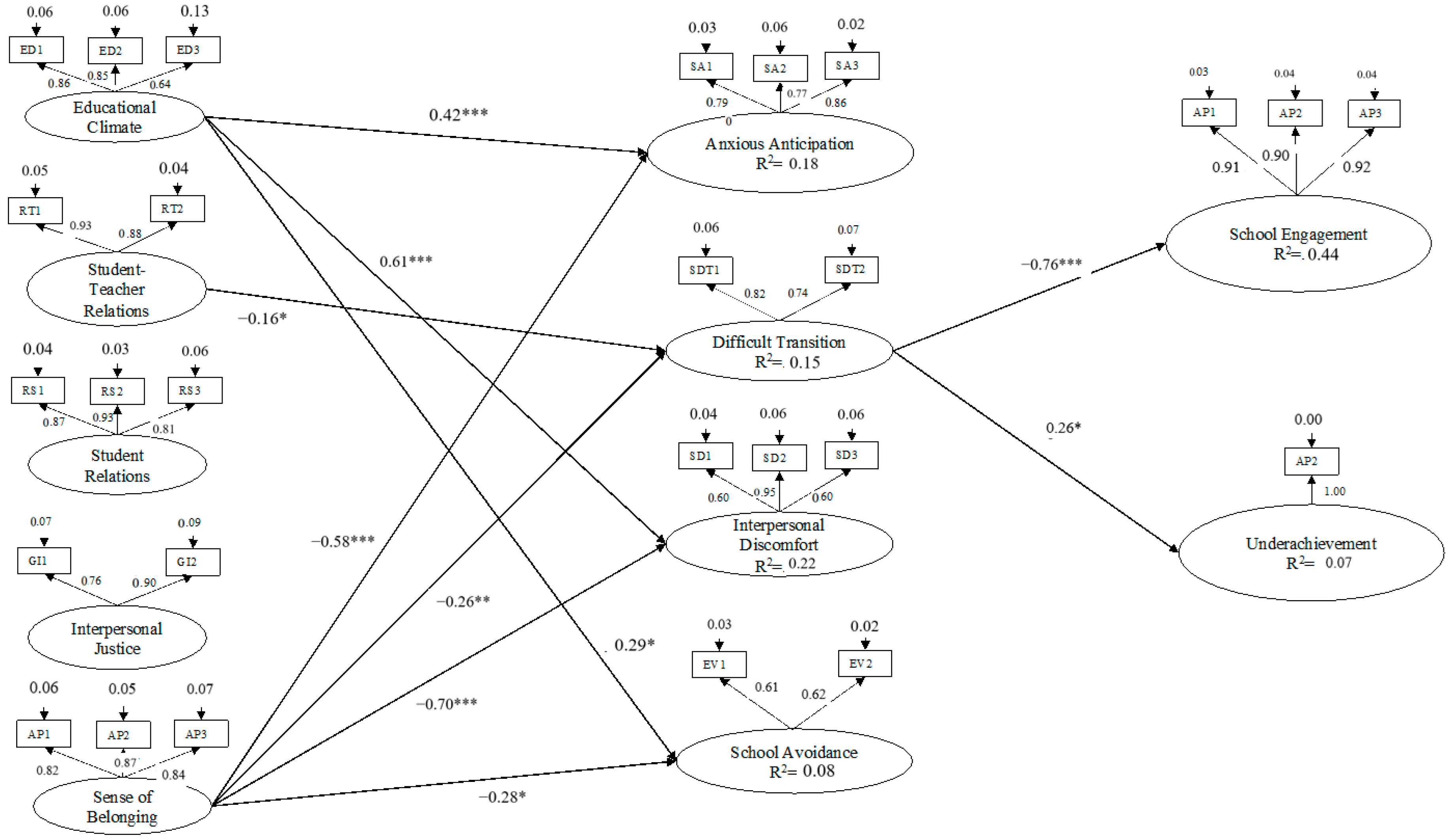

| β | SE | Lower Bound (BC) 95% CI | Upper Bound (BC) 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | |||||

| Educational Climate → Anxious Anticipation | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.42 | ≤0.001 |

| Sense of Belonging → Anxious Anticipation | −0.58 | 0.06 | −0.45 | −0.21 | ≤0.001 |

| Student–Teacher Relations → Difficult Transition | −0.16 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.16 | ≤0.05 |

| Sense of Belonging → Difficult Transition | −0.26 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.26 | ≤0.01 |

| Educational Climate → Interpersonal Discomfort | 0.61 | 0.06 | −0.23 | −0.69 | ≤0.001 |

| Sense of Belonging → Interpersonal Discomfort | 0.70 | 0.06 | −0.23 | −0.69 | ≤0.001 |

| Educational Climate → School Avoidance | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.28 | ≤0.05 |

| Sense of Belonging → School Avoidance | −0.28 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.27 | ≤0.05 |

| Difficult Transition → School Engagement | −0.76 | 0.18 | −0.81 | −0.76 | ≤0.001 |

| Difficult Transition → Underachievement | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.26 | ≤0.05 |

| Indirect Effect via Difficult Transition | |||||

| Sense of Belonging → School Engagement | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.45 | 0.20 | ≤0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorrenti, L.; Caparello, C.; Meduri, C.F.; Filippello, P. The Mediating Role of School Refusal in the Relationship Between Students’ Perceived School Atmosphere and Underachievement. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15010001

Sorrenti L, Caparello C, Meduri CF, Filippello P. The Mediating Role of School Refusal in the Relationship Between Students’ Perceived School Atmosphere and Underachievement. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorrenti, Luana, Concettina Caparello, Carmelo Francesco Meduri, and Pina Filippello. 2025. "The Mediating Role of School Refusal in the Relationship Between Students’ Perceived School Atmosphere and Underachievement" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15010001

APA StyleSorrenti, L., Caparello, C., Meduri, C. F., & Filippello, P. (2025). The Mediating Role of School Refusal in the Relationship Between Students’ Perceived School Atmosphere and Underachievement. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15010001