A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of the Motivational Climate and Hedonic Well-Being Constructs: The Importance of the Athlete Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. AGT and Motivational Climate History

1.2. Study Purposes, Hypotheses, and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

2.2. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Search Protocol

- Examined Harwood et al.’s studies [9] for terms to aid in our search.

- Began the EBSCOhost search.

- Selected the following individual databases: APA PsycArticles, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PsychINFO, and SPORTDiscus.

- Selected EBSCOhost advanced search.

- Typed in search terms using the Boolean operator AND.

- Limited EBSCOhost to scholarly peer-reviewed journals.

- Selected page options for 50 records per page.

- Conducted EBSCOhost searches as described below. After our first search (Search 1), we compared each search to all preceding searches to eliminate duplicates.

- Search 1: motivational climate, wellbeing well-being well being, sport (n = 66).

- Search 2: motivational climate, burnout, sport (n = 25 with 17 non-duplicates).

- Search 3: motivational climate, flourishing, sport (n = 0).

- Search 4: motivational climate, resilience, sport (n = 7 with 4 non-duplicates).

- Search 5: motivational climate, satisfaction with life, sport (n = 8 with 2 non-duplicates).

- Search 6: motivational climate, depression, sport (n = 7 with 3 non-duplicates).

- Search 7: motivational climate, positive affect or negative affect, sport (n = 24 with 13 non-duplicates).

- Search 8: motivational climate, mental health, sport (n = 17 with 10 non-duplicates).

- Search 9: motivational climate, need satisfaction, sport (n = 31 with 21 non-duplicates).

- Search 10: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 1993–1999 (n = 12 with 12 non-duplicates).

- Search 11: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2000–2004 (n = 10 with 8 non-duplicates).

- Search 12: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2005–2009 (n = 19 with 12 non-duplicates).

- Search 13: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2010–2014 (n = 27 with 6 non-duplicates).

- Search 14: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2015–2017 (n = 18 with 10 non-duplicates).

- Search 15: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2018–2019 (n = 19 with 8 non-duplicates).

- Search 16: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2020–2021 (n = 11 with 5 non-duplicates).

- Search 17: motivational climate, satisfaction (in abstract), sport, 2022–2023 until 1 November 2023 (n = 15 with 5 non-duplicates).

- Search 18: Review of Birr et al. [34] for studies reporting either the task-involving or ego-involving climate subscales within the EDMCQ-C (n = 10 with 8 non-duplicates).

- Search 19: hand searched Google Scholar with motivational climate AND sport (n = 7 non-duplicates).

- Search 20: motivational climate, anxiety (in abstract), sport 1995–2005 (n = 10 with 1 non-duplicate).

- Search 21: motivational climate, anxiety (in abstract), sport 2006–2010 (n = 12 with 0 non-duplicates).

- Search 22: motivational climate, anxiety (in abstract), sport 2011–2017 (n = 27 with 19 non-duplicates).

- Search 23: motivational climate, anxiety (in abstract), sport 2018–2023 (n = 20 with 10 non-duplicates).

- Search 24: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 1992–2000 (n = 8 with 6 non-duplicates).

- Search 25: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2001–2005 (n = 9 with 4 non-duplicates).

- Search 26: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2000–2011 (n = 27 with 21 non-duplicates).

- Search 27: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2012–2015 (n = 24 with 19 non-duplicates).

- Search 28: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2016 (n = 8 with 5 non-duplicates).

- Search 29: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2017 (n = 10 with 8 non-duplicates).

- Search 30: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2018–2019 (n = 14 with 8 non-duplicates).

- Search 31: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2020–2021 (n = 9 with 6 non-duplicates).

- Search 32: motivational climate, enjoyment or joy or fun or pleasure (in abstract), sport 2022–2023 (n = 7 with 5 non-duplicates).

- Search 33: Checked our included studies with Harwood et al. [9] (n = 1 non-duplicate).

2.3. Data Collection and Items Retrieved

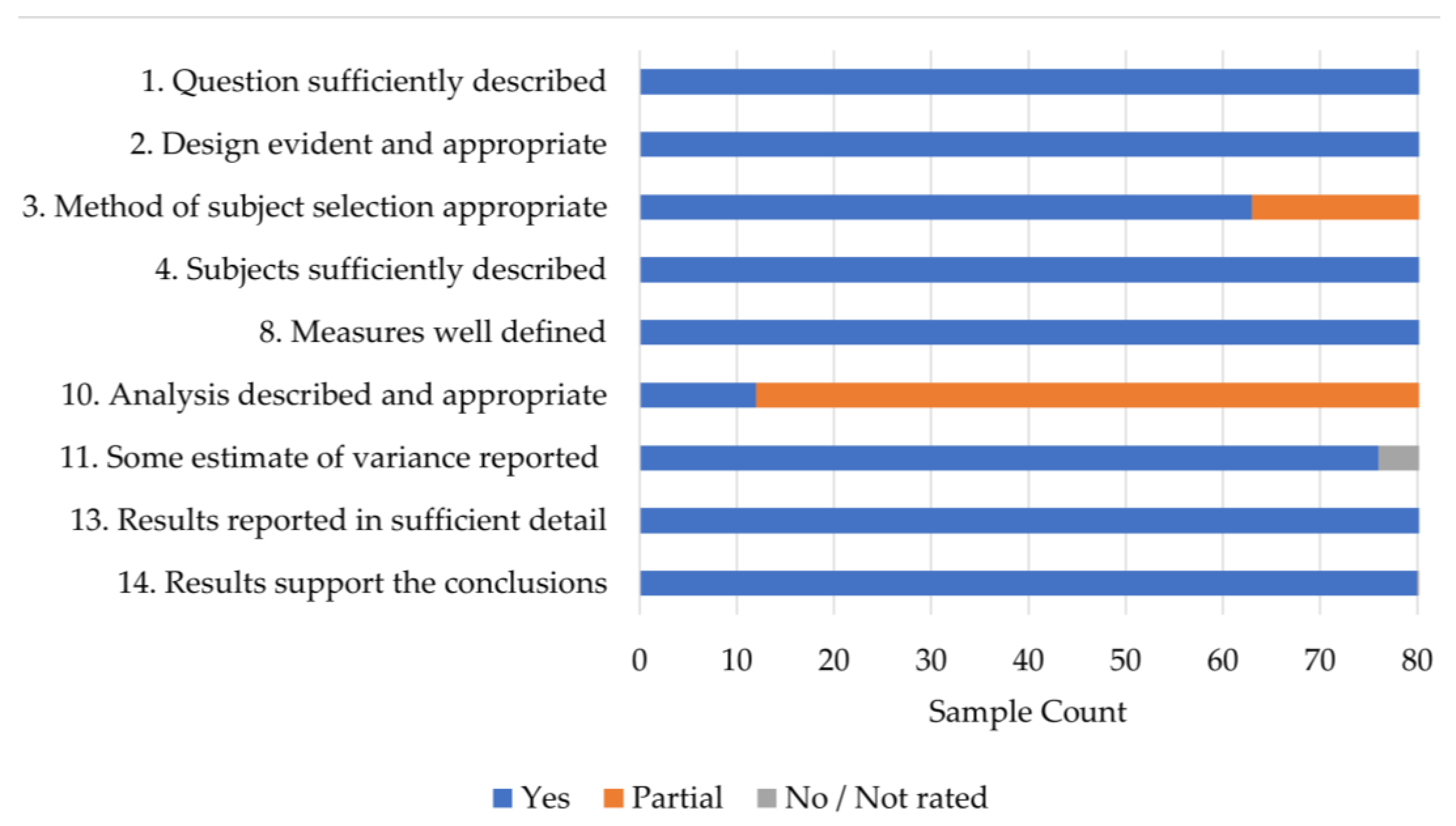

2.4. Study Quality and Risk of Bias Assessments

2.5. Summary Statistics, Planned Analyses, and Certainty Assessment

3. Results

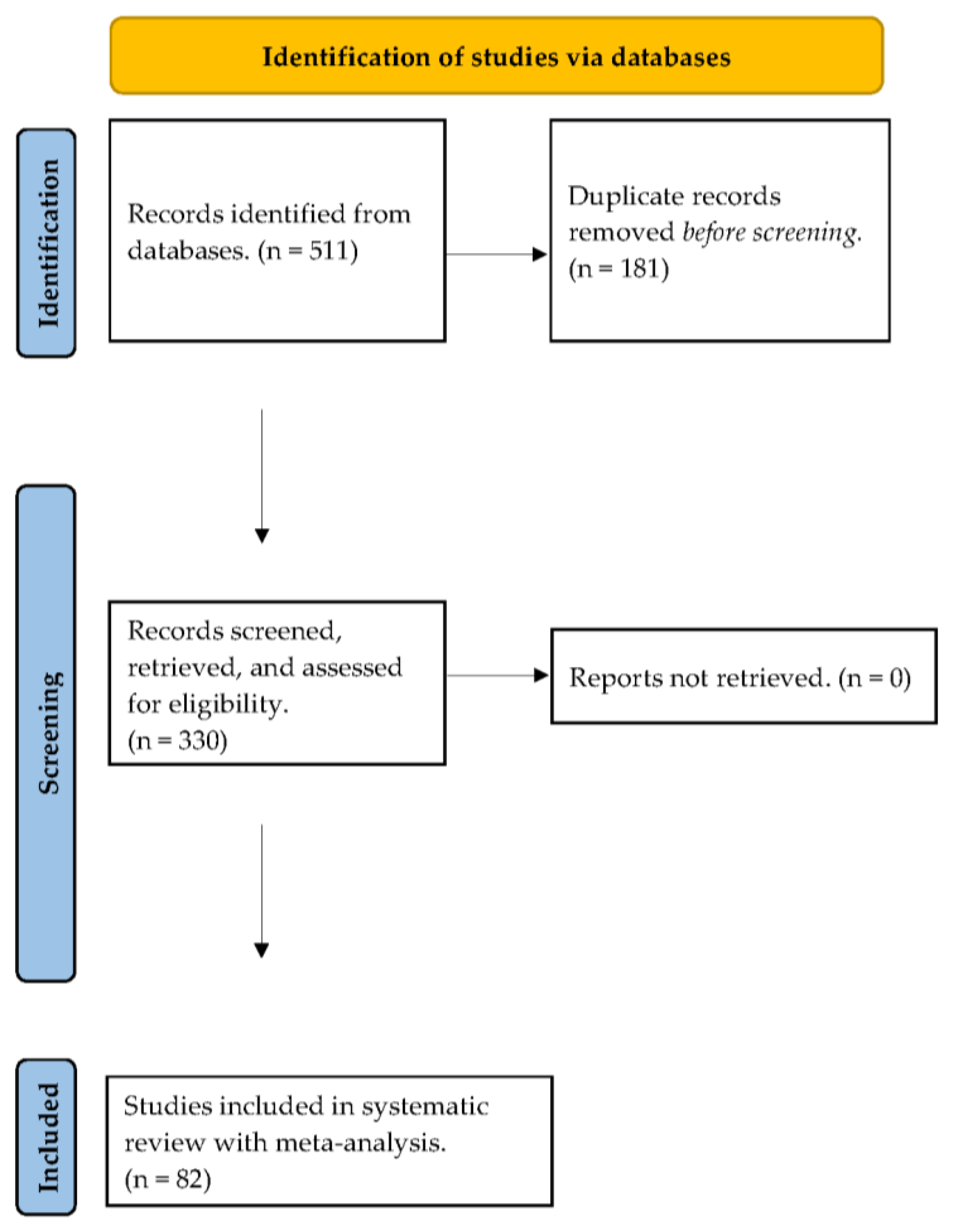

3.1. Study Selection, Characteristics, and Quality

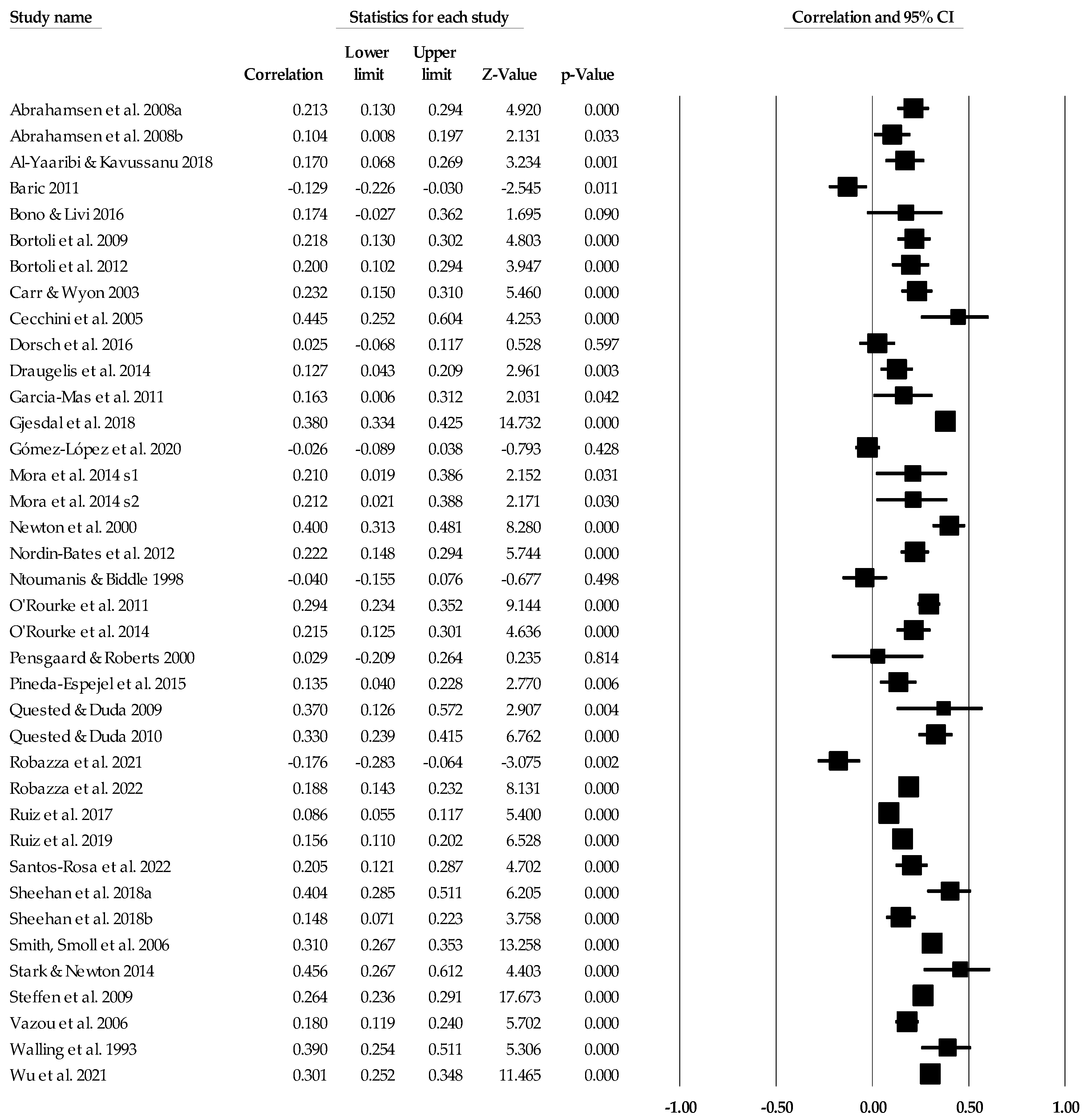

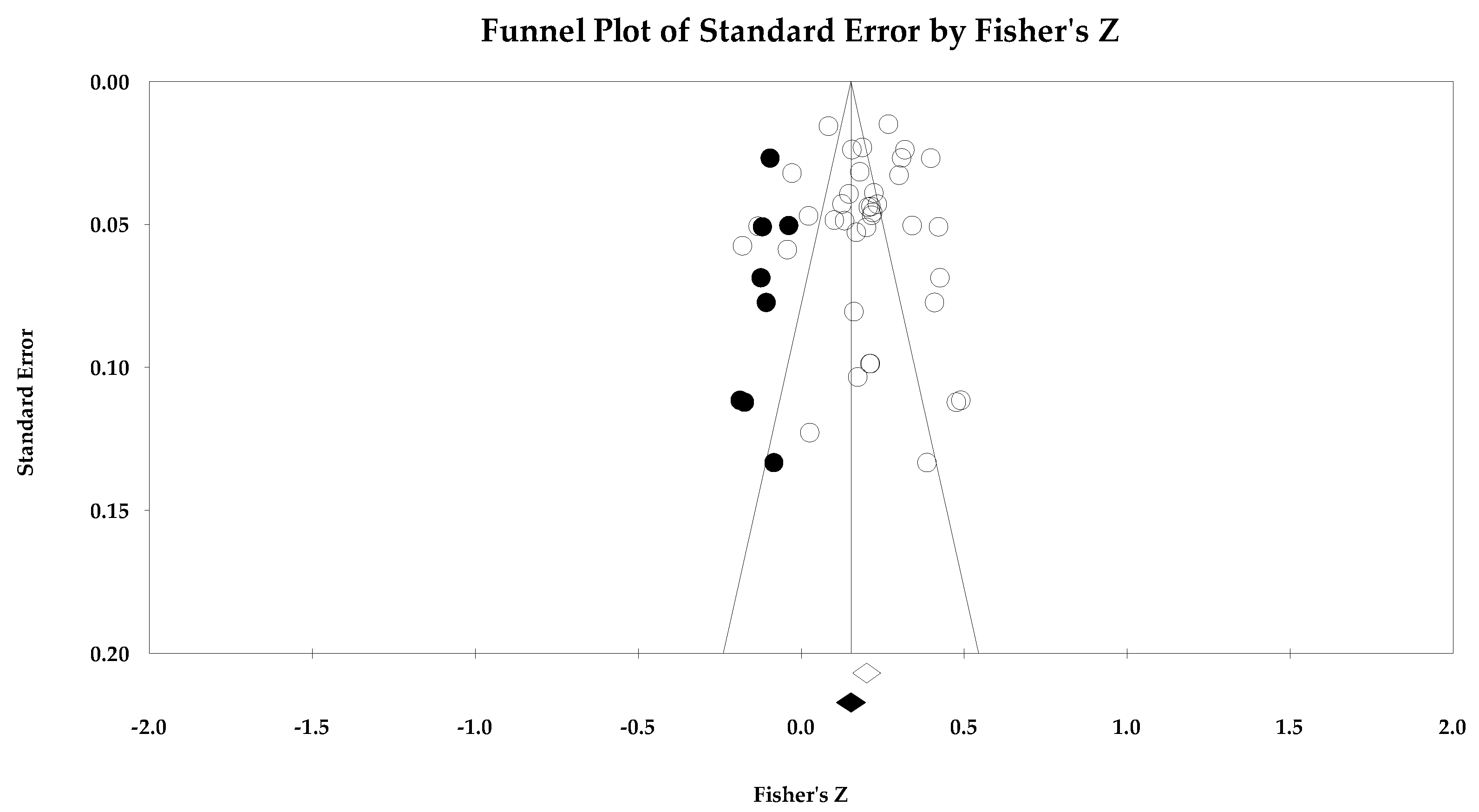

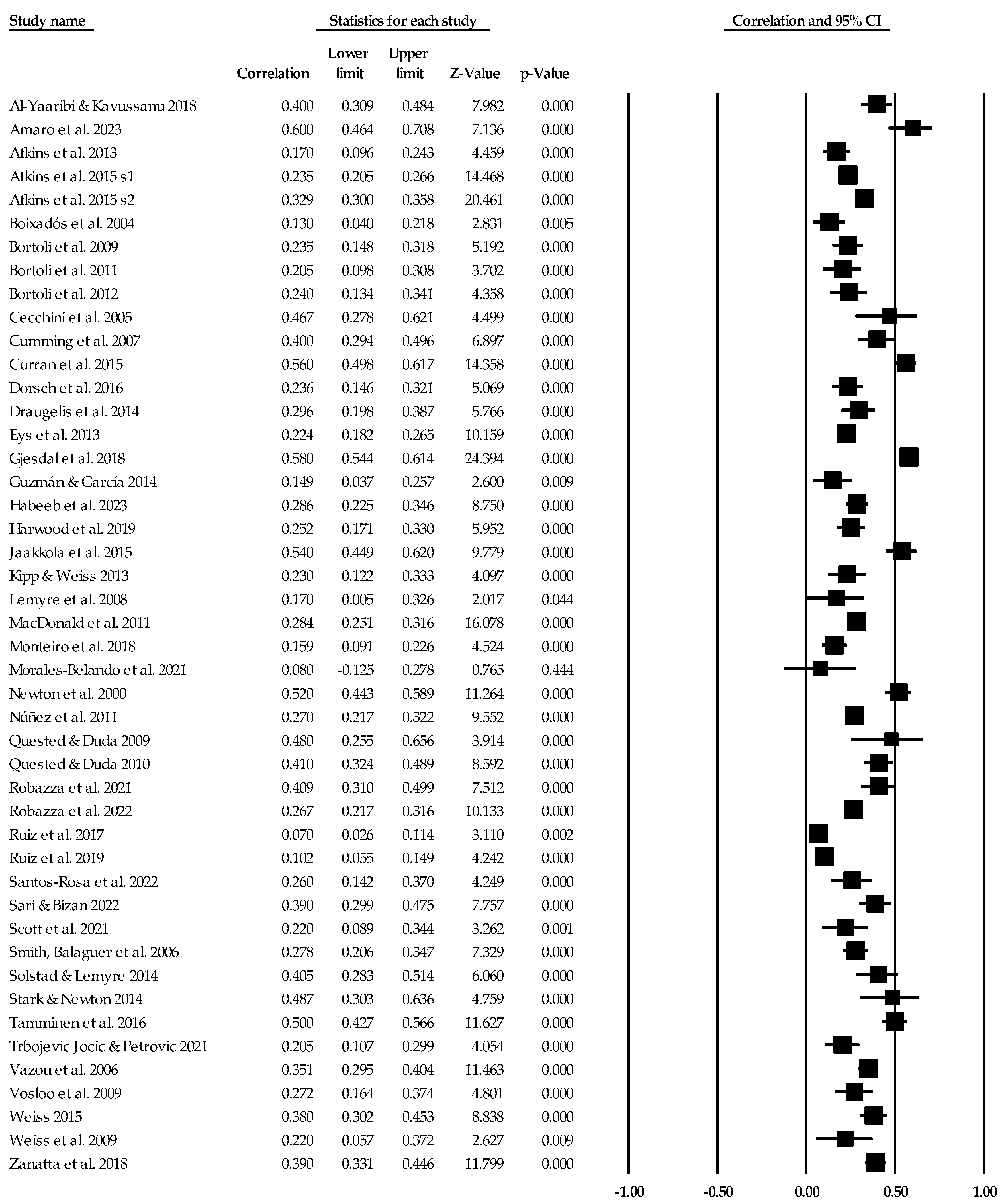

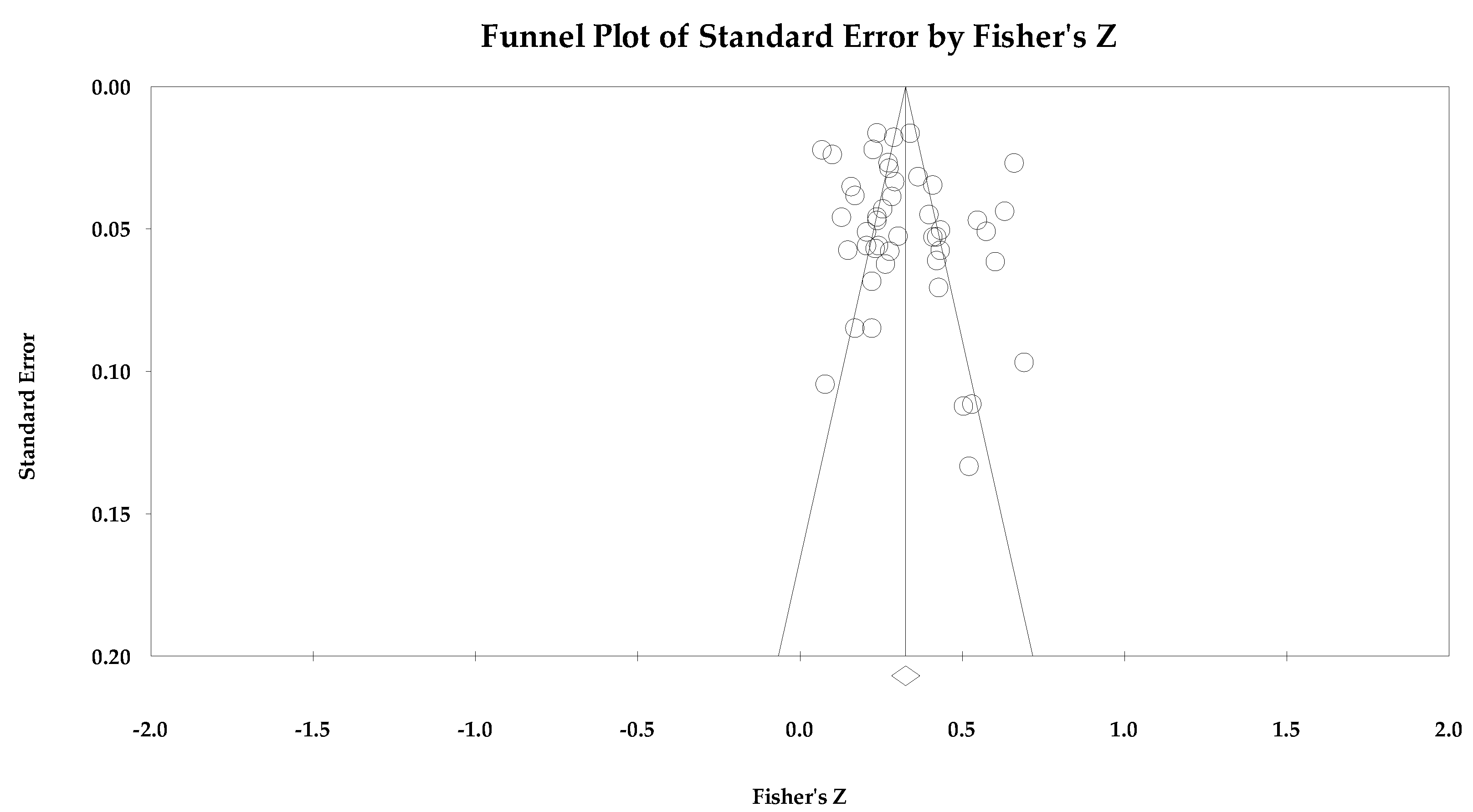

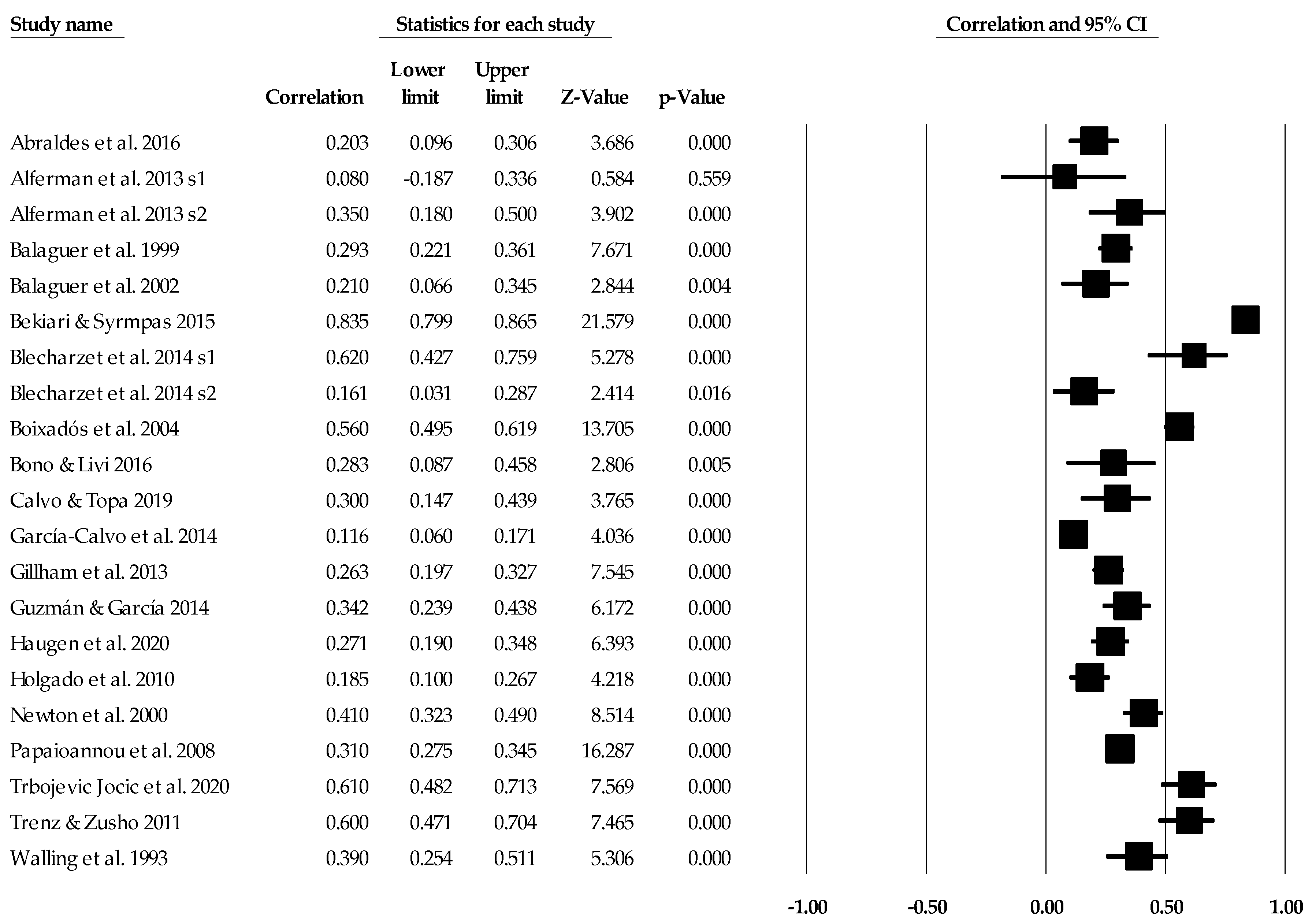

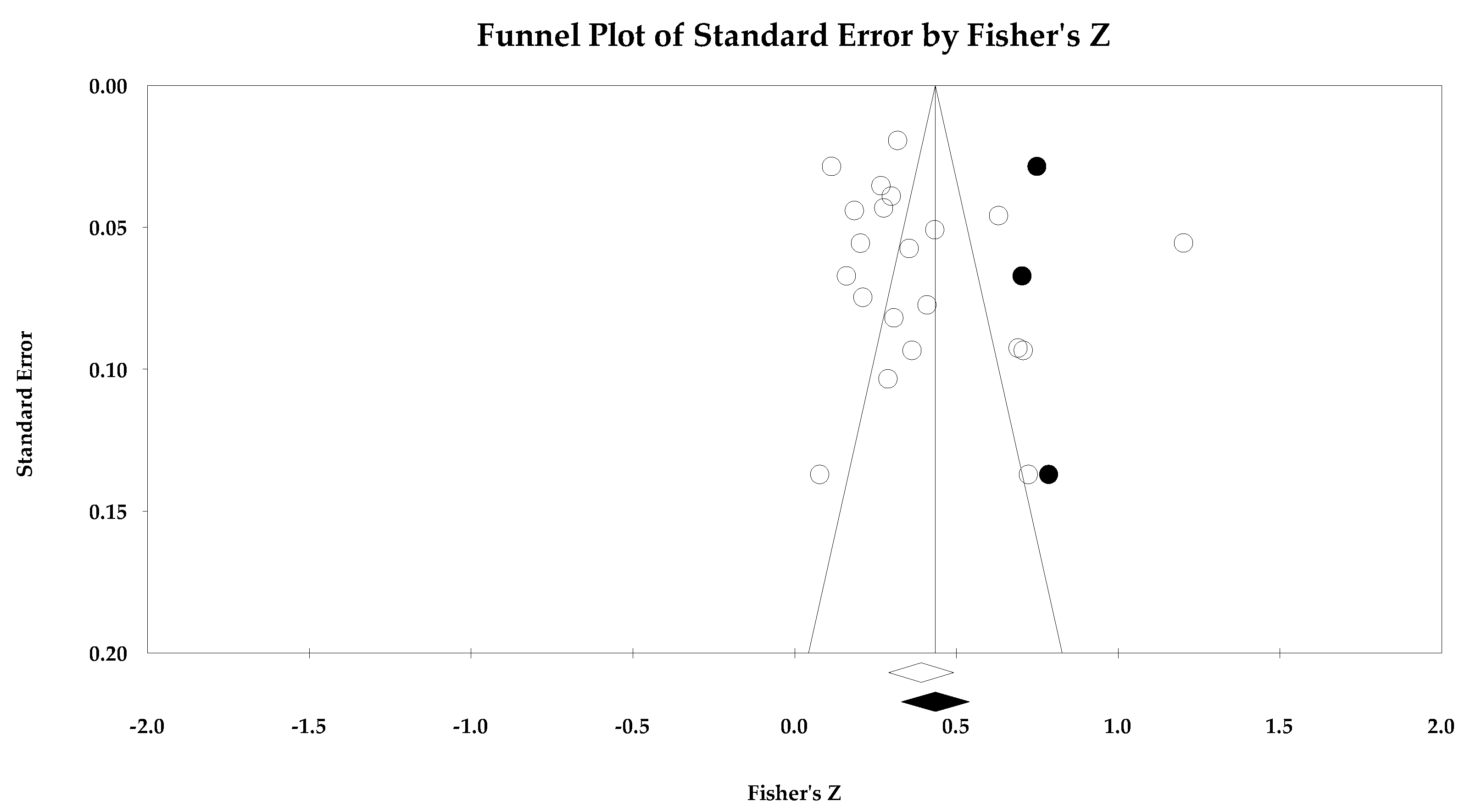

3.2. Task Climate Individual Study Data, Synthesis of Results, and Risk of Bias across Studies

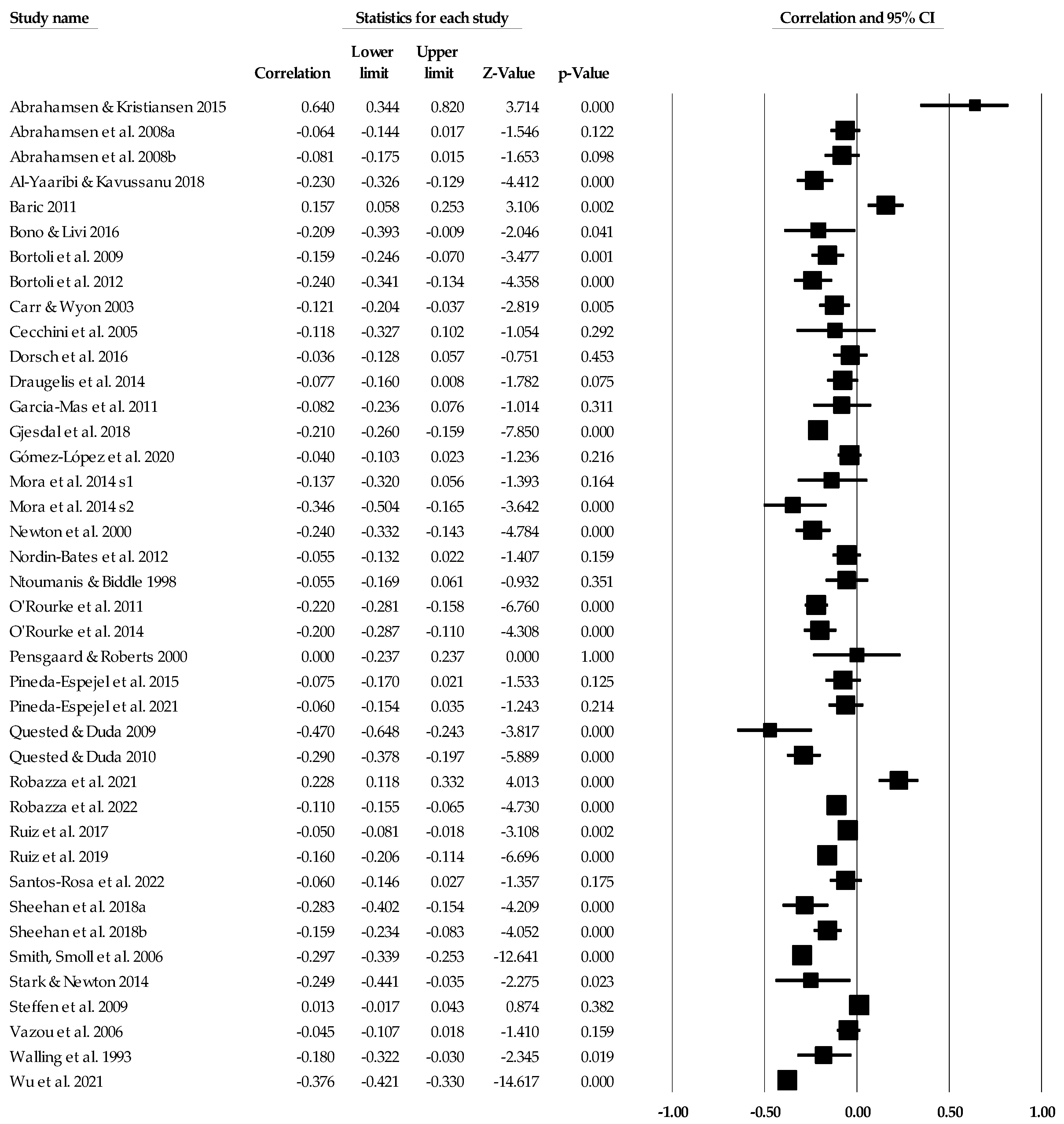

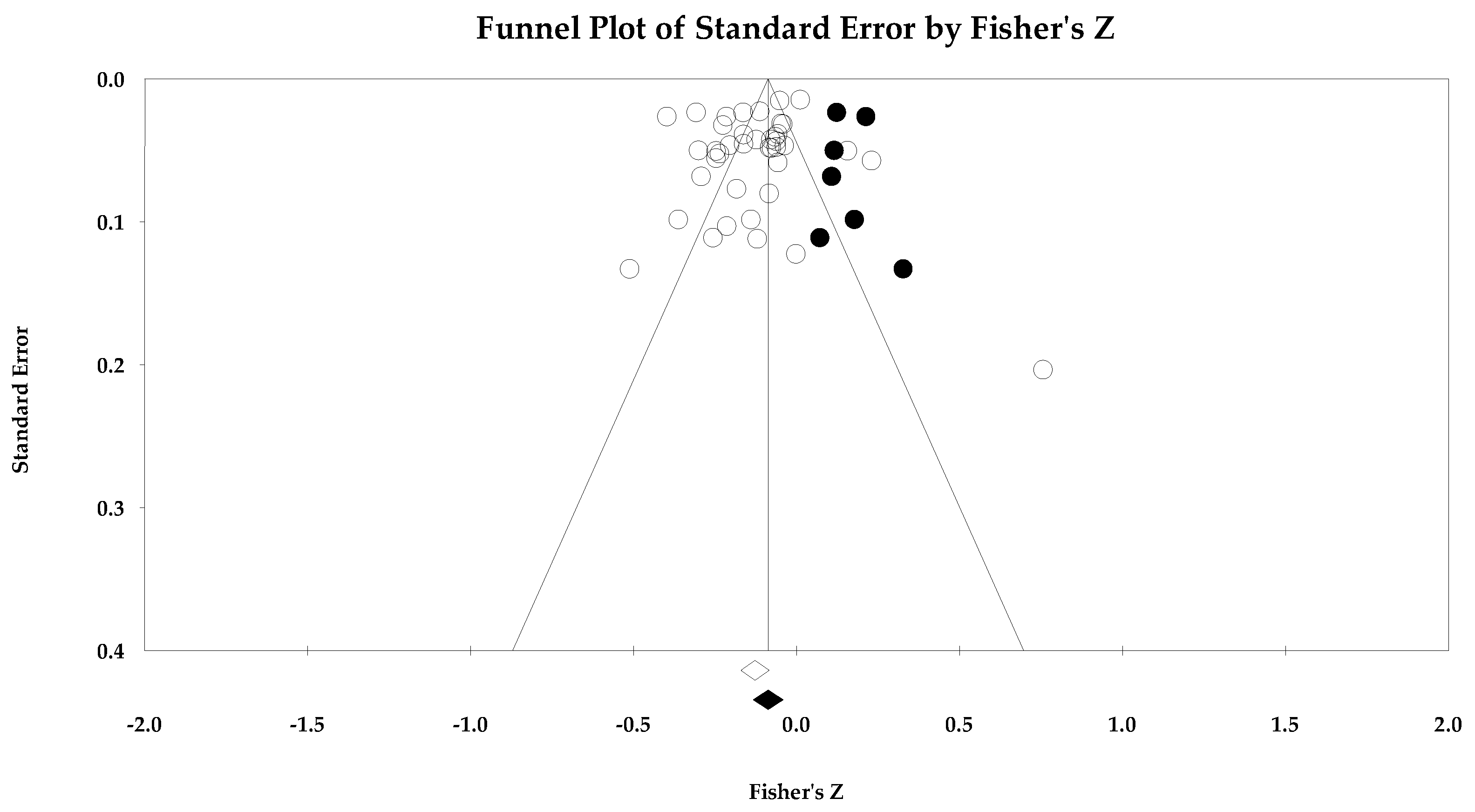

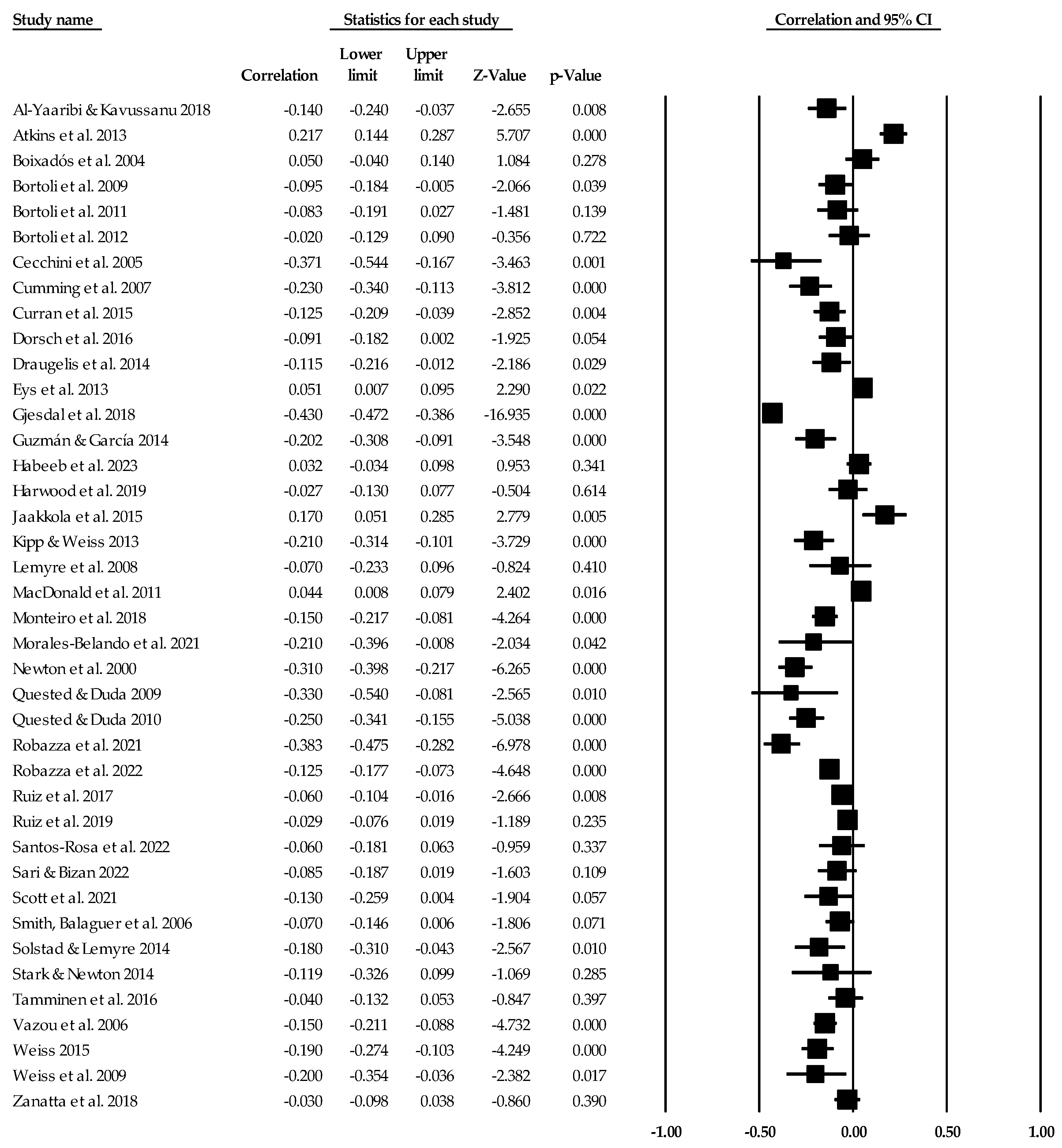

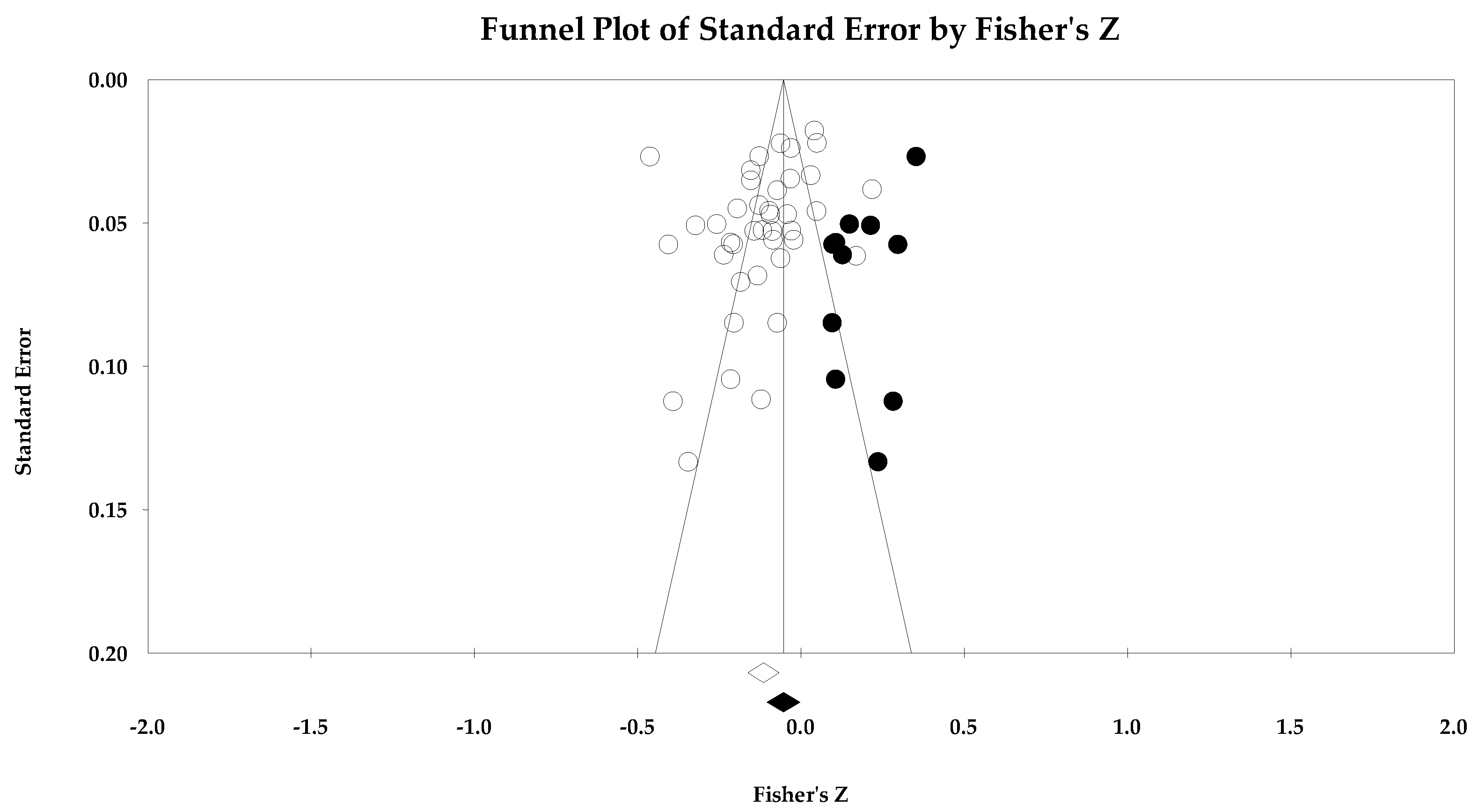

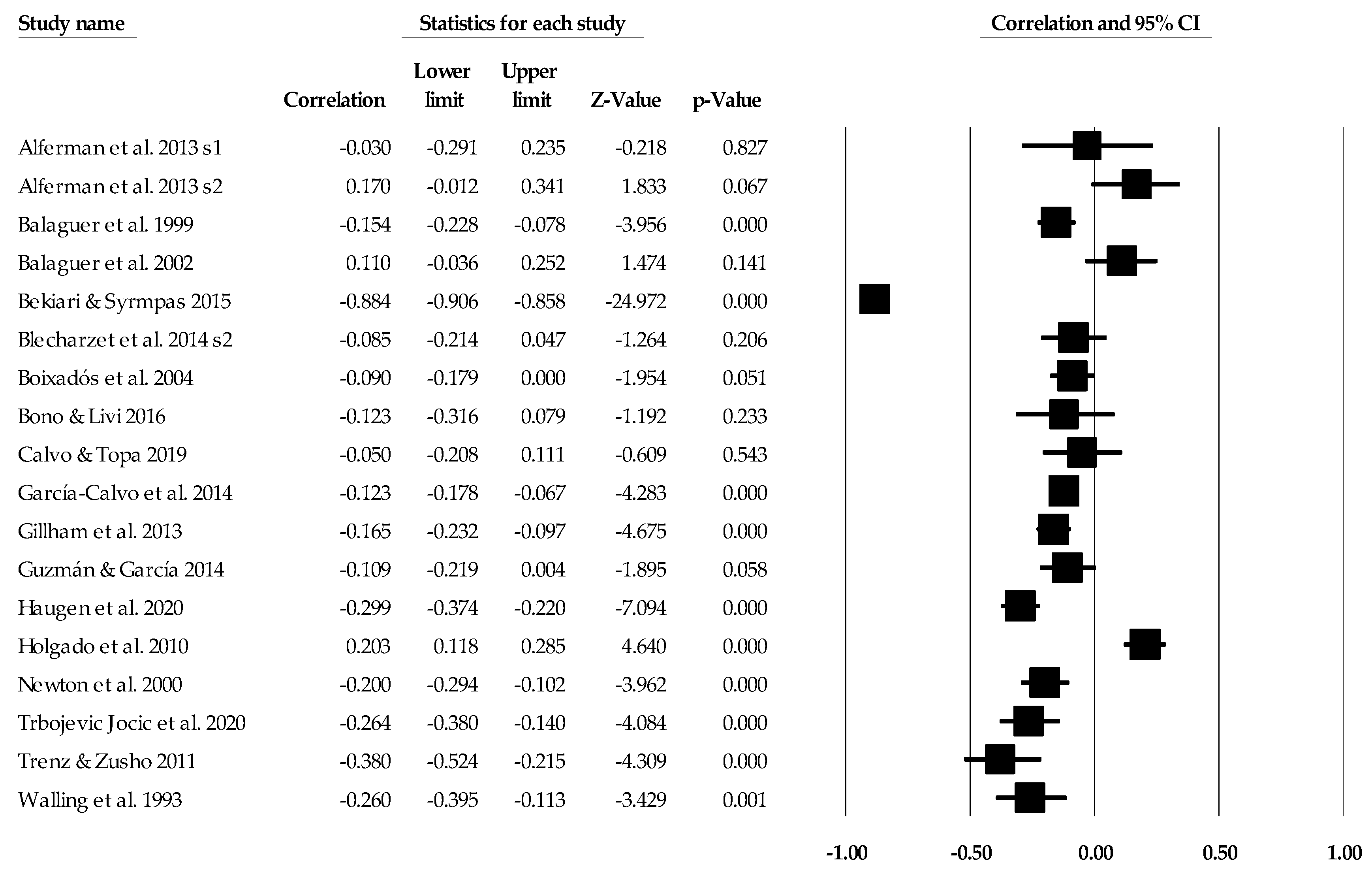

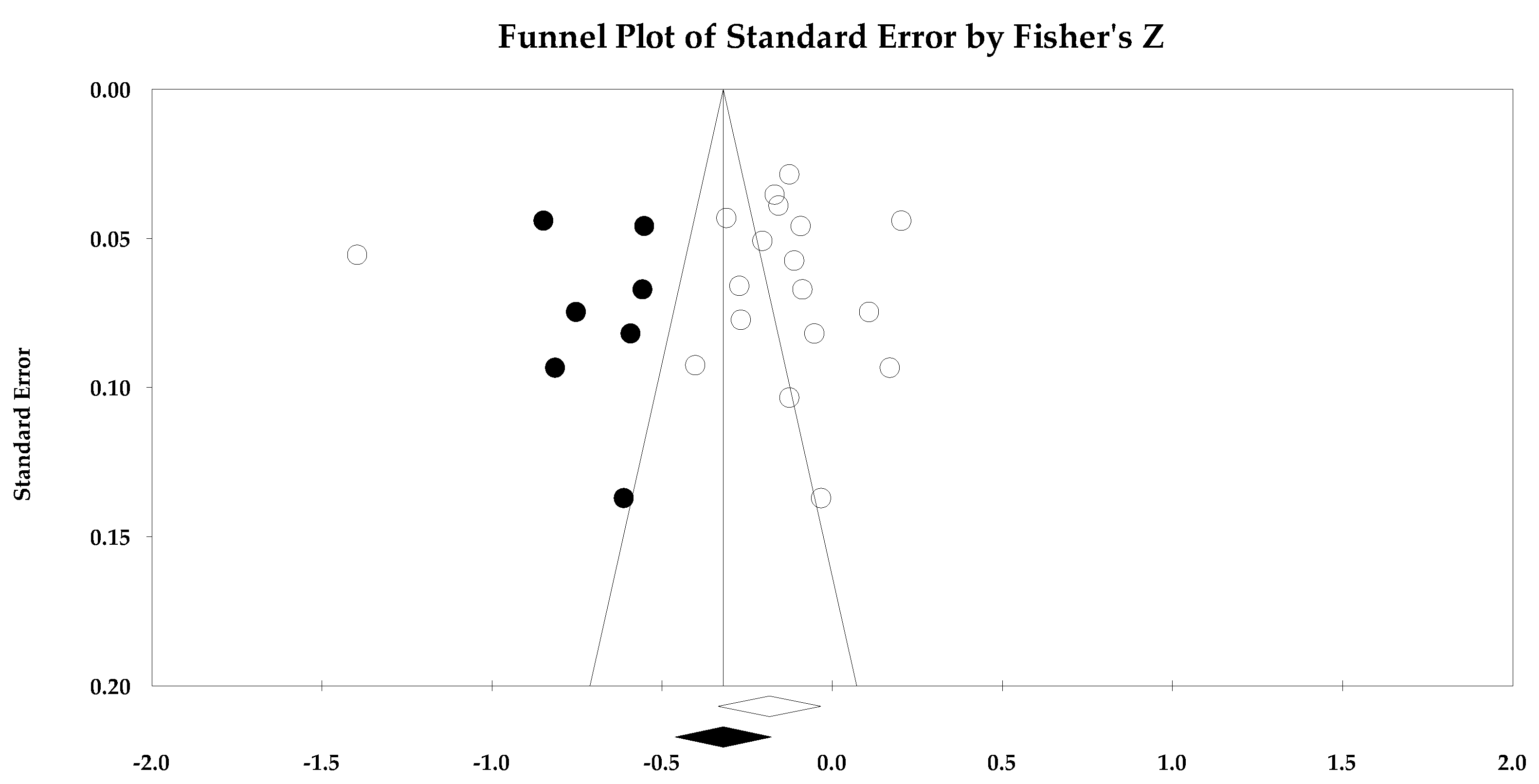

3.3. Ego Climate Individual Study Data, Synthesis of Results, and Risk of Bias across Studies

3.4. Additional Sensitivity Analyses

3.5. Moderator Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, Future Directions, and Applications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ames, C. The Enhancement of Student Motivation; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1987; Volume 5, pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, C.; Archer, J. Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.; Elliot, E. Achievement Motivation; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 643–691. [Google Scholar]

- Maehr, M.L. Meaning and Motivation: Toward a Theory of Personal Investment; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.G. Conceptions of Ability and Achievement Motivation; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lochbaum, M.; Kazak Çetinkalp, Z.; Graham, K.A.; Wright, T.; Zazo, R. Task and ego goal orientations in competitive sport: A quantitative review of the literature from 1989 to 2016. Kinesiology 2016, 48, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zazo, R.; Kazak Çetinkalp, Z.; Wright, T.; Graham, K.A.; Konttinen, N. A meta-analytic review of achievement goal orientation correlates in competitive sport: A follow-up to Lochbaum et al.(2016). Kinesiology 2016, 48, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Biddle, S. Affect and achievement goals in physical activity: A meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 1999, 9, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, C.G.; Keegan, R.J.; Smith, J.M.; Raine, A.S. A systematic review of the intrapersonal correlates of motivational climate perceptions in sport and physical activity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 18, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Biddle, S. A review of motivational climate in physical activity. J. Sports Sci. 1999, 17, 643–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifriz, J.J.; Duda, J.L.; Chi, L. The relationship of perceived motivational climate to intrinsic motivation and beliefs about success in basketball. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1992, 14, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.A.; Duda, J.L.; Hart, S. An exploratory examination of the parent-initiated motivational climate questionnaire. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1992, 75, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, L.R.; Bundon, A. Clarifying concepts:“Well-being” in sport. Front. Sports Act. Living. 2023, 5, 1256490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.C.; Balagué, G. The development of a social-cognitive scale of motivation. In Proceedings of the Seventh World Congress of Sport Psychology, Singapore, 7–12 July 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G.C.; Balagué, G. The development and validation of the Perception of Success Questionnaire. In Proceedings of the 8th European Congress (FEPSAC), Cologne, Germany, 4–9 July 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G.C. Motivation in Sport and Exercise: Conceptual Constraints and Convergence; Roberts, G.C., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, S.; Wang, C.K.J.; Kavussanu, M.; Spray, C. Correlates of achievement goal orientations in physical activity: A systematic review of research. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2003, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.L. Relationship between Task and Ego Orientation and the Perceived Purpose of Sport among High School Athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1989, 11, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.L.; Nicholls, J.G. Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, A.; Filgueiras, A.; Campos, M.; Keegan, R.; Landeira-Fernández, J. Motivational Climate Measures in Sport: A Systematic Review. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.E.; Cumming, S.P.; Smoll, F.L. Development and validation of the motivational climate scale for youth sports. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2008, 20, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, P.R.; Ntoumanis, N.; Quested, E.; Viladrich, C.; Duda, J.L. Initial validation of the coach-created Empowering and Disempowering Motivational Climate Questionnaire (EDMCQ-C). Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.; Duda, J.L.; Yin, Z. Examination of the psychometric properties of the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, R.; Spray, C.M.; Warburton, V.E. Motivational climate interventions in physical education: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, F.E.; Roberts, G.C.; Pensgaard, A.M. Achievement goals and gender effects on multidimensional anxiety in national elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.E.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software; Version 4; Biostat, Inc.: Englewood, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M. Common Mistakes in Meta-Analysis and How to Avoid Them; Biostat, Inc.: Englewood, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lochbaum, M.; Sisneros, C.; Kazak, Z. The 3 × 2 Achievement Goals in the Education, Sport, and Occupation Literatures: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1130–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochbaum, M.; Sisneros, C.; Cooper, S.; Terry, P.C. Pre-Event Self-Efficacy and Sports Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports 2023, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochbaum, M.; Cooper, S.; Limp, S. The Athletic Identity Measurement Scale: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis from 1993 to 2021. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 1391–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birr, C.; Hernandez-Mendo, A.; Monteiro, D.; Rosado, A. Empowering and Disempowering Motivational Coaching Climate: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet, L.M.; Cook, L.S.; Lee, R.C. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orwin, R.G. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. J. Educ. Stat. 1983, 8, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Brit. Med. J. 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Things I have learned (so far). Am. Psychol. Assoc. 1990, 45, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, M.D.; Duda, J.L.; Chi, L. The perceived motivational climate in sport questionnaire: Construct and predictive validity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1993, 15, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Biddle, S. The relationship between competitive anxiety, achievement goals, and motivational climates. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1998, 69, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaguer, I.; Duda, J.; Crespo, M. Motivational climate and goal orientations as predictors of perceptions of improvement, satisfaction and coach ratings among tennis players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 1999, 9, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pensgaard, A.M.; Roberts, G.C. The relationship between motivational climate, perceived ability and sources of distress among elite athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaguer, I.; Duda, J.L.; Atienza, F.L.; Mayo, C. Situational and dispositional goals as predictors of perceptions of individual and team improvement, satisfaction and coach ratings among elite female handball teams. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2002, 3, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Wyon, M. The impact of motivational climate on dance students’ achievement goals, trait anxiety, and perfectionism. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2003, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boixados, M.; Cruz, J.; Torregrosa, M.; Valiente, L. Relationships among motivational climate, satisfaction, perceived ability, and fair play attitudes in young soccer players. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2004, 16, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, J.A.; González, C.; Prado, J.L.; Brustad, R.J. Relación del clima motivacional percibido con la orientación de meta, la motivación intrínseca y las opiniones y conductas de fair play. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2005, 22, 469–479. [Google Scholar]

- Vazou, S.; Ntoumanis, N.; Duda, J.L. Predicting young athletes’ motivational indices as a function of their perceptions of the coach-and peer-created climate. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.L.; Balaguer, I.; Duda, J.L. Goal orientation profile differences on perceived motivational climate, perceived peer relationships, and motivation-related responses of youth athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Smoll, F.L.; Cumming, S.P.; Grossbard, J.R. Measurement of multidimensional sport performance anxiety in children and adults: The Sport Anxiety Scale-2. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, S.P.; Smoll, F.L.; Smith, R.E.; Grossbard, J.R. Is winning everything? The relative contributions of motivational climate and won-lost percentage in youth sports. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2007, 19, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, F.; Roberts, G.; Pensgaard, A.; Ronglan, L. Perceived ability and social support as mediators of achievement motivation and performance anxiety. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2008, 18, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemyre, P.N.; Hall, H.; Roberts, G. A social cognitive approach to burnout in elite athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2008, 18, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaioannou, A.G.; Ampatzoglou, G.; Kalogiannis, P.; Sagovits, A. Social agents, achievement goals, satisfaction and academic achievement in youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, E.; Duda, J.L. Perceptions of the motivational climate, need satisfaction, and indices of well-and ill-being among hip hop dancers. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2009, 13, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, K.; Pensgaard, A.; Bahr, R. Self-reported psychological characteristics as risk factors for injuries in female youth football. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2009, 19, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosloo, J.; Ostrow, A.; Watson, J.C. The relationships between motivational climate, goal orientations, anxiety, and self-confidence among swimmers. J. Sport Behav. 2009, 32, 376–393. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M.R.; Amorose, A.J.; Wilko, A.M. Coaching behaviors, motivational climate, and psychosocial outcomes among female adolescent athletes. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2009, 21, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Robazza, C. Dispositional goal orientations, motivational climate, and psychobiosocial states in youth sport. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, E.; Duda, J.L. Exploring the social-environmental determinants of well-and ill-being in dancers: A test of basic needs theory. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado, F.P.; Navas, L.; López-Núñez, M. Orientaciones de Meta en el deporte: Un modelo causal. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 3, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barić, R. Psychological pressure and athletes’ perception of motivational climate in team sports. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 18, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, D.J.; Smith, R.E.; Smoll, F.L.; Cumming, S.P. Trait anxiety in young athletes as a function of parental pressure and motivational climate: Is parental pressure always harmful? J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2011, 23, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.J.; Côté, J.; Eys, M.; Deakin, J. The role of enjoyment and motivational climate in relation to the personal development of team sport athletes. Sport Psychol. 2011, 25, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.L.; León, J.; González, V.; Martín-Albo, J. Propuesta de un modelo explicativo del bienestar psicológico en el contexto deportivo. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2011, 20, 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Trenz, R.C.; Zusho, A. Competitive swimmers’ perception of motivational climate and their personal achievement goals. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2011, 6, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoli, L.; Bertollo, M.; Comani, S.; Robazza, C. Competence, achievement goals, motivational climate, and pleasant psychobiosocial states in youth sport. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Mas, A.; Palou, P.; Smith, R.; Ponseti, X.; Almeida, H.G.L.d.; Lameiras, J.; Jiménez, R.; Leiva, A. Ansiedad competitiva y clima motivacional en jóvenes futbolistas de competición, en relación con las habilidades y el rendimiento percibido por sus entrenadores. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2011, 20, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoli, L.; Messina, G.; Zorba, M.; Robazza, C. Contextual and individual influences on antisocial behaviour and psychobiosocial states of youth soccer players. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin-Bates, S.M.; Quested, E.; Walker, I.J.; Redding, E. Climate change in the dance studio: Findings from the UK centres for advanced training. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2012, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gillham, A.; Burton, D.; Gillham, E. Going beyond won-loss record to identify successful coaches: Development and preliminary validation of the Coaching Success Questionnaire-2. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2013, 8, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfermann, D.; Geisler, G.; Okade, Y. Goal orientation, evaluative fear, and perceived coach behavior among competitive youth swimmers in Germany and Japan. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eys, M.A.; Jewitt, E.; Evans, M.B.; Wolf, S.; Bruner, M.W.; Loughead, T.M. Coach-initiated motivational climate and cohesion in youth sport. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2013, 84, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipp, L.E.; Weiss, M.R. Social influences, psychological need satisfaction, and well-being among female adolescent gymnasts. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2013, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.R.; Johnson, D.M.; Force, E.C.; Petrie, T.A. “Do I still want to play?” Parents’ and peers’ influences on girls’ continuation in sport. J. Sport Behav. 2013, 36, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Blecharz, J.; Luszczynska, A.; Tenenbaum, G.; Scholz, U.; Cieslak, R. Self-efficacy moderates but collective efficacy mediates between motivational climate and athletes’ well-being. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 6, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draugelis, S.; Martin, J.; Garn, A. Psychosocial predictors of well-being in collegiate dancers. Sport Psychol. 2014, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Calvo, T.; Leo, F.M.; Gonzalez-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Mouratidis, A.; Ntoumanis, N. Perceived coach-created and peer-created motivational climates and their associations with team cohesion and athlete satisfaction: Evidence from a longitudinal study. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, D.J.; Smith, R.E.; Smoll, F.L.; Cumming, S.P. Relations of parent-and coach-initiated motivational climates to young athletes’ self-esteem, performance anxiety, and autonomous motivation: Who is more influential? J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2014, 26, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A.; Newton, M. A dancer’s well-being: The influence of the social psychological climate during adolescence. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.; García, C.G. Psychological well-being in dancers: A social cognitive analysis. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fis. Deporte 2014, 14, 687. [Google Scholar]

- Solstad, B.E.; Lemyre, P.N. Why Coaches should Encourage Swimmers’ Efforts to Succeed. J. Swim. Res. 2014, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, À.; Sousa, C.; Cruz, J. El clima motivacional, l’autoestima i l’ansietat en jugadors joves d’un club de basquetbol. Apunts. Educ. Fís. Deporte 2014, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jaakkola, T.; Ntoumanis, N.; Liukkonen, J. Motivational climate, goal orientation, perceived sport ability, and enjoyment within Finnish junior ice hockey players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 26, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Espejel, A.; Walle, J.L.; Tomás, I. Factores situacionales y disposicionales como predictores de la ansiedad y autoconfianza precompetitiva en deportistas universitarios. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2015, 15, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, F.E.; Kristiansen, E. The dark side of a mastery emphasis: Can mastery involvement create stress and anxiety? Int. J. Appl. Sports Sci. 2015, 27, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiari, A.; Syrmpas, I. Coaches’ verbal aggressiveness and motivational climate as predictors of athletes’ satisfaction. Br. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 9, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, W.M. Competitive-level differences on sport commitment among high school-and collegiate-level athletes. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 13, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.R.; Johnson, D.M.; Force, E.C.; Petrie, T.A. Peers, parents, and coaches, oh my! The relation of the motivational climate to boys’ intention to continue in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K.; Jowett, G.E. Relationships between the coach-created motivational climate and athlete engagement in youth sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraldes, J.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Gómez-López, M.; Rodríguez-Suárez, N. Goal orientations, satisfaction, beliefs in sport success and motivational climate in swimmers. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fis. 2016, 16, 583–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, B.; Livi, S. Motivazione al successo in atleti di élite: Applicazione del 2 × 2 achievement goal framework nel nuoto. [Achievement motivation in elite athletes: Application of 2 × 2 achievement goal framework in swimming]. Rass. Psicol. 2016, 33, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, A.L.; Dotterer, A.M. Individual, relationship, and context factors associated with parent support and pressure in organized youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 23, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, K.A.; Gaudreau, P.; McEwen, C.E.; Crocker, P.R. Interpersonal emotion regulation among adolescent athletes: A Bayesian multilevel model predicting sport enjoyment and commitment. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.C.; Haapanen, S.; Tolvanen, A.; Robazza, C.; Duda, J.L. Predicting athletes’ functional and dysfunctional emotions: The role of the motivational climate and motivation regulations. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanatta, T.; Rottensteiner, C.; Konttinen, N.; Lochbaum, M. Individual motivations, motivational climate, enjoyment, and physical competence perceptions in finnish team sport athletes: A prospective and retrospective study. Sports 2018, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yaaribi, A.; Kavussanu, M. Consequences of prosocial and antisocial behaviors in adolescent male soccer players: The moderating role of motivational climate. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 37, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, D.; Pelletier, L.G.; Moutão, J.; Cid, L. Examining the motivational determinants of enjoyment and the intention to continue of persistent competitive swimmers. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2018, 49, 484–504. [Google Scholar]

- Gjesdal, S.; Haug, E.M.; Ommundsen, Y. A conditional process analysis of the coach-created mastery climate, task goal orientation, and competence satisfaction in youth soccer: The moderating role of controlling coach behavior. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2019, 31, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, R.B.; Herring, M.P.; Campbell, M.J. Associations between motivation and mental health in sport: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, R.B.; Herring, M.P.; Campbell, M.J. Longitudinal relations of mental health and motivation among elite student-athletes across a condensed season: Plausible influence of academic and athletic schedule. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 37, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.C.; Robazza, C.; Tolvanen, A.; Haapanen, S.; Duda, J.L. Coach-created motivational climate and athletes’ adaptation to psychological stress: Temporal motivation-emotion interplay. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, C.G.; Caglar, E.; Thrower, S.N.; Smith, J.M. Development and validation of the parent-initiated motivational climate in individual sport competition questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, C.; Topa, G. Leadership and motivational climate: The relationship with objectives, commitment, and satisfaction in base soccer players. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.; Riesen, J.F.; Østrem, K.; Høigaard, R.; Erikstad, M.K. The Relationship between Motivational Climate and Personal Treatment Satisfaction among Young Soccer Players in Norway: The Moderating Role of Supportive Coach-Behaviour. Sports 2020, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, M.; Chicau Borrego, C.; Marques da Silva, C.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; González-Hernández, J. Effects of motivational climate on fear of failure and anxiety in teen handball players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trbojević, J.; Mandarić, S.; Petrović, J. Perceived motivational climate created by coach and physical self-efficacy as predictors of the young Serbian female athletes satisfaction. Fiz. Kult. 2020, 74, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zainal Abidin, N.E.; Aga Mohd Jaladin, R. Motivational processes influencing mental health among winter sports athletes in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 726072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Espejel, H.A.; Alarcón, E.; Morquecho-Sánchez, R.; Morales-Sánchez, V.; Gadea-Cavazos, E. Adaptive social factors and precompetitive anxiety in elite sport. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 651169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.E.; Fry, M.D.; Weingartner, H.; Wineinger, T.O. Collegiate sport club athletes’ psychological well-being and perceptions of their team climate. Recreat. Sports J. 2021, 45, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robazza, C.; Ruiz, M.C.; Bortoli, L. Psychobiosocial experiences in sport: Development and initial validation of a semantic differential scale. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 55, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Belando, M.T.; Côté, J.; Arias-Estero, J.L. A longitudinal examination of the influence of winning or losing with motivational climate as a mediator on enjoyment, perceived competence, and intention to be physically active in youth basketball. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 28, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trbojević, J.; Petrović, J. Understanding of dropping out of sports in adolescence–testing the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Kinesiology 2021, 53, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, İ.; Bizan, İ. The role of parent-initiated motivational climate in athletes’ engagement and dispositional flow. Kinesiology 2022, 54, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rosa, F.J.; Montero-Carretero, C.; Gómez-Landero, L.A.; Torregrossa, M.; Cervelló, E. Positive and negative spontaneous self-talk and performance in gymnastics: The role of contextual, personal and situational factors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robazza, C.; Morano, M.; Bortoli, L.; Ruiz, M.C. Perceived motivational climate influences athletes’ emotion regulation strategies, emotions, and psychobiosocial experiences. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 59, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, N.; Monteiro, D.; Rodrigues, F.; Matos, R.; Jacinto, M.; Cavaco, B.; Jorge, S.; Antunes, R. Task-Involving Motivational Climate and Enjoyment in Youth Male Football Athletes: The Mediation Role of Self-Determined Motivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habeeb, C.M.; Barbee, J.; Raedeke, T.D. Association of parent, coach, and peer motivational climate with high school athlete burnout and engagement: Comparing mediation and moderation models. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 68, 102471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, S.; Stenling, A.; Solstad, B.E.; Ommundsen, Y. A study of coach-team perceptual distance concerning the coach-created motivational climate in youth sport. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 29, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegan, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Hodge, K.; Jackson, S.A. Athlete engagement: II. Developmental and initial validation of the Athlete Engagement Questionnaire. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2007, 38, 471–492. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M.C.; Hanin, Y.L.; Robazza, C. Assessment of performance-related experiences: An individualized approach. Sport Psychol. 2016, 30, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, T.K.; Carpenter, P.J.; Schmidt, G.W.; Simons, J.P.; Keeler, B. An Introduction to the Sport Commitment Model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1993, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, T.K.; Chow, G.M.; Sousa, C.; Scanlan, L.A.; Knifsend, C.A. The development of the sport commitment questionnaire-2 (English version). Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-González, M.; Pino-Ortega, J.; Clemente, F.; Los Arcos, A. Guidelines for performing systematic reviews in sports science. Biol. Sport 2022, 39, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, S.; Castro, O.; Bahrami, F.; Tomporowski, P.D.; Capranica, L.; Biddle, S.J.; Pesce, C. Martial arts, combat sports, and mental health in adults: A systematic review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 70, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyllo, L.B.; Landers, D.M. Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1995, 17, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C.; Moran, A.; Piggott, D. Defining elite athlete issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Climate Measure | Subscales | Example Questions |

|---|---|---|

| PMCSQ [11] | Mastery Climate Performance Climate | On this team, trying hard is rewarded. (Mastery Climate) The only thing that matters is winning. (Performance Climate) |

| PMCSQ-2 [24] | Task-involving Climate (Subscales: Important Role, Cooperative Learning, and Effort/Improvement) Ego-involving Climate (Subscales: Intra-Team Member Rivalry, Punishment for Mistakes, and Unequal Recognition) | On this team, the coach wants us to try new skills. (Task-involving) On this team, the coach makes it clear who they think are the best players. (Ego-involving) |

| MCSYS [22] | Mastery Climate Performance Climate | The coach encouraged us to learn new skills. (Mastery Climate) Winning games was the most important thing for the coach. (Performance Climate) |

| EDMCQ-C [23] | Task-involving Climate Ego-involving Climate Autonomy-supportive Climate Socially Supportive Climate Controlling Climate | My coach made sure players felt successful when they improved. (Task-involving Climate) My coach yelled at players for messing up. (Ego-involving Climate) |

| Category | Category Specifics |

|---|---|

| Elite | International competitions at highest level (e.g., Olympics), professional leagues (e.g., Premier leagues), described by authors as elite, samples >18 years of age |

| Advanced | College athletes in all countries, youth/adolescents in country or professional team talent programs, and national-level competition |

| Intermediate | 14–18 years of age, USA high school, club, not identified as elite or in college, in organized training and regional-level competition |

| Recreational | Uni intramural, adults on city teams not listed above at regional level or with extensive training schedules |

| Youth | Sample mean age <14 unless listed in a category above, below high school |

| Mix | Unable to determine one category for sample data |

| Quality Questions | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Question or objective sufficiently described? |

| 2 | Design evident and appropriate to answer study question? |

| 3 | Is method of subject selection (and comparison group selection, if applicable) or source of information/input variables (e.g., for decision analysis) described and appropriate? |

| 4 | Subject (and comparison group, if applicable) characteristics or input variables/information (e.g., for decision analyses) sufficiently described? |

| 5 | If random allocation to treatment group was possible, is it described? N/A: Observational analytic studies. Uncontrolled experimental studies. Surveys. |

| 6 | If interventional and blinding of investigators to intervention was possible, is it reported? N/A: Observational analytic studies. Surveys. Descriptive case series/reports. |

| 7 | If interventional and blinding of subjects to intervention was possible, is it reported? N/A: Observational studies. Surveys. Descriptive case series/reports. |

| 8 | Outcome and (if applicable) exposure measure(s) well defined and robust to measurement/misclassification bias? Means of assessment reported? |

| 9 | Sample size appropriate? N/A: Most surveys (except surveys comparing responses between groups or change over time) |

| 10 | Analysis described and appropriate? |

| 11 | Some estimate of variance (e.g., confidence intervals, standard errors) is reported for the main results/outcomes? |

| 12 | Controlled for confounding? N/A: Cross-sectional surveys of a single group. Descriptive studies. |

| 13 | Results reported in sufficient detail? |

| 14 | Do the results support the conclusions? |

| Participant Characteristics | Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Year | N (%F) | Country | Level | Sport | Climate | Correlate |

| Walling et al. [41] | 1993 | 169 (50.8) | US | A/E | Mix Team | PMCSQ | NA, SAT |

| Ntoumanis & Biddle [42] | 1998 | 146 (42.4) | UK | A | Mix Team | PMCSQ | NA |

| Balaguer et al. [43] | 1999 | 219 (33.3) | ES | Mix | Tennis | PMCSQ | SAT |

| Pensgaard & Roberts [44] | 2000 | 69 (28.9) | NO | E | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ | NA |

| Newton et al. [24] | 2000 | 385 (100) | US | I/A | Volleyball | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA, SAT |

| Balaguer et al. [45] | 2002 | 181 (100) | ES | A | Handball | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Carr & Wyon [46] | 2003 | 181 (87.2) | UK | A | Dance | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Boixadós et al. [47] | 2004 | 472 (0) | ES | Y | Soccer | PMCSQ | PA, SAT |

| Cecchini et al. [48] | 2005 | 82 (0) | ES | I/A | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA, SAT |

| Vazou et al. [49] | 2006 | 493 (25.1) | UK | I | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Smith, Balaguer et al. [50] | 2006 | 223 (0) | ES | Y | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | PA, SAT |

| Smith, Smoll et al. [51] | 2006 | 1038 (44.9) | US | Y | Mix Team | MCSYS | NA |

| Cumming et al. [52] | 2007 | 268 (39.1) | US | Y | Basketball | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Abrahamsen et al. [53] | 2008a | 190 (46.8) | NO | A/E | Mix IND | PMCSQ | NA |

| Abrahamsen et al. [26] | 2008b | 143 (48.2) | NO | E | Handball | PMCSQ | NA |

| Lemyre et al. [54] | 2008 | 141 (42.5) | NO | E | Mix IND | PMCSQ | SAT |

| Papaioannou et al. [55] | 2008 | 863 (43.1) | GR | Y/I | Mix IND, Team | PSAEGO | SAT |

| Quested & Duda [56] | 2009 | 59 (64.4) | UK | A | Hip Hop Dancing | PMCSQ | PA, NA |

| Steffen et al. [57] | 2009 | 1430 (100) | NO | I | Soccer | PMCSQ | NA |

| Vosloo et al. [58] | 2009 | 151 (61.5) | US | I | Swimming | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Weiss et al. [59] | 2009 | 141 (100) | US | I | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Bortoli et al. [60] | 2009 | 473 (45.8) | IT | Y | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ | PA, NA |

| Quested & Duda [61] | 2010 | 392 (74.7) | UK | A | Dancing | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Holgado et al. [62] | 2010 | 511 (31.1) | ES | E | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Barić [63] | 2011 | 388 (0) | HR | I | Mix Team | PMCSQ | NA |

| O’Rourke et al. [64] | 2011 | 307 (60.2) | US | I | Swimming | PIMCQ-2 | NA |

| MacDonald et al. [65] | 2011 | 510 (52.5) | CA | Mix | Mix IND, Team | MCSYS | PA |

| Núñez et al. [66] | 2011 | 399 (29.5) | MX | Mix | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Trenz & Zusho [67] | 2011 | 119 (64.7) | US | Mix | Swim | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Bortoli et al. [68] | 2011 | 320 (50.0) | IT | Y | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ | PA, NA |

| Garcia-Mas et al. [69] | 2011 | 54 (0) | ES | Y | Soccer | MCSYS | NA |

| Bortoli et al. [70] | 2012 | 382 (0) | IT | I | Soccer | PMCSQ | PA, NA |

| Nordin-Bates et al. [71] | 2012 | 327 (75.7) | UK | Mix | Dance | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Gillham et al. [72] | 2013 | 396 (57.3) | US | A | Mix IND, Team | MCSYS | SAT |

| Alfermann et al. [73] | 2013 | 56, 117 (51.2) | DE, JP | A/E | Swim | PMCSQ | SAT |

| Eys et al. [74] | 2013 | 997 (53.3) | CA | I | Mix IND, Team | MCSYS | PA |

| Kipp & Weiss [75] | 2013 | 309 (100) | US | I | Gymnastics | MCSYS | PA |

| Atkins et al. [76] | 2013 | 227 (100) | US | Mix | Soccer | PeerMCYSQ | PA |

| Blecharz et al. s1 [77] | 2014 | 56 (64.0) | PL | A/E | Mix Team | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Blecharz et al. s2 [77] | 2014 | 113 (0) | PL | A | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Draugelis et al. [78] | 2014 | 182 (86.3) | US | A | Dance | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| García-Calvo et al. [79] | 2014 | 303 (0) | ES | A | Soccer | PMCSQ-2, PeerMCYSQ | SAT |

| O’Rourke et al. [80] | 2014 | 228 (59.2) | US | I | Swimming | PIMCQ-2 MCSYS | NA |

| Stark & Newton [81] | 2014 | 83 (100) | US | I | Dance | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Guzmán & García [82] | 2014 | 303 (82.8) | ES | Mix | Dance | PMCSQ | PA, SAT |

| Solstad & Lemyre [83] | 2014 | 202 (51.0) | NO | Mix | Swim | MCSYS | PA, NA |

| Mora et al. [84] | 2014 | 40 (NR) | ES | Y/I | Basketball | PMCSQ-2, PeerMCYSQ | NA |

| Jaakkola et al. [85] | 2015 | 265 (0) | FI | A | Ice Hockey | MCPES | PA |

| Pineda-Espejel et al. [86] | 2015 | 211 (54.7) | ES | A | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Abrahamsen & Kristiansen [87] | 2015 | 27 (0) | Mix | E | Soccer | PMCSQ | NA |

| Bekiari & Syrmpas [88] | 2015 | 324 (40.1) | GR | I | Mix IND, Team | LAPOPEQ | SAT |

| Weiss [89] | 2015 | 491 (49.6) | US | I/A | NR | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Atkins et al. [90] | 2015 | 405 (0) | US | Y | Mix IND, Team | PeerMCYSQ PIMCQ-2 PMCSQ-2 MCSYS | PA |

| Curran et al. [91] | 2015 | 260 (57.6) | UK | Y | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Abraldes et al. [92] | 2016 | 163 (43.5) | ES | A | Swim | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Bono & Livi [93] | 2016 | 96 (44.0) | IT | A/E | Swim | PMCSQ | NA |

| Dorsch et al. [94] | 2016 | 226 (39.8) | US | Mix | Mix Team | MCSYS | PA, NA |

| Tamminen et al. [95] | 2016 | 451 (45.2) | CA | Mix | Mix Team | PeerMCSYS | PA |

| Ruiz et al. [96] | 2017 | 494 (42.7) | FI | A/E | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Zanatta et al. [97] | 2018 | 824 (40.6) | FI | I | Mix Team | PMCSQ | PA |

| Al-Yaaribi & Kavussanu [98] | 2018 | 358 (0) | UK | I | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Monteiro et al. [99] | 2018 | 799 (43.6) | PT | I/A | Swimming | MCSYS | PA |

| Gjesdal et al. [100] | 2018 | 1359 (42.2) | SE | Y | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Sheehan et al. [101] | 2018a | 38 (47.3) | IE | A | Mix Team | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Sheehan et al. [102] | 2018b | 215 (65.0) | IE | A/E | Mix Team | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Ruiz et al. [103] | 2019 | 217 (41.9) | FI | A/E | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Harwood et al. [104] | 2019 | 92 (35.8) | UK | I | Tennis | MCISCQ-F/M | PA |

| Calvo & Topa [105] | 2019 | 151 (NR) | ES | Mix | Soccer | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Haugen et al. [106] | 2020 | 532 (31.4) | NO | A | Soccer | PMCSQ | SAT |

| Gómez-López et al. [107] | 2020 | 479 (47.8) | ES | I | Handball | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Trbojević et al. [108] | 2020 | 117 (100) | RS | Y/I | Mix Team | PMCSQ-2 | SAT |

| Wu et al. [109] | 2021 | 685 (44.9) | CN | A | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Pineda-Espejel et al. [110] | 2021 | 217 (48.3) | ES | E | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | NA |

| Scott et al. [111] | 2021 | 109 (35.8) | US | I/A | Mix Team | PMCSQ | PA |

| Robazza et al. [112] | 2021 | 302 (41.0) | IT | Mix | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Morales-Belando et al. [113] | 2021 | 94 (2.1) | ES | Y | Basketball | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Trbojević Jocić & Petrović [114] | 2021 | 383 (50.1) | RS | Y/I | Mix Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA |

| Sarı & Bizan [115] | 2022 | 180 (54.4) | TR | I | Mix IND, Team | PIMCQ-2 | PA |

| Santos-Rosa et al. [116] | 2022 | 258 (100) | ES | I | Rhythmic Gymnastics | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Robazza et al. [117] | 2022 | 459 (43.7) | IT | Mix | Mix IND, Team | PMCSQ-2 | PA, NA |

| Amaro et al. [118] | 2023 | 109 (0) | PT | I | Soccer | MCSYS | PA |

| Habeeb et al. [119] | 2023 | 150 (43.3) | US | I | Mix IND, Team | PIMCQ-2 PeerMCYSQ MCSYS | PA |

| Effect Size Statistics | Heterogeneity Statistics | Bias Statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlate | k | r | 95% CI | 95% PI | Q | τ2 | I2 | FS | Orwin | Trim/Fill | r [95% CI] |

| PA | 46 | 0.31 | 0.27, 0.35 | 0.04, 0.57 | 662.11 | 0.02 | 93.20 | 43,500 | 89 | 0 | No change |

| NA | 40 | −0.13 | −0.17, −0.08 | −0.36, 0.13 | 451.80 | 0.02 | 91.37 | 4886 | 7 | 7R | −0.09 [−0.13, −0.04] |

| 39 A | −0.13 | −0.18, −0.09 | −0.37, 0.11 | 433.46 | 0.02 | 91.23 | 5067 | 7 | 8R | −0.09 [−0.14, −0.05] | |

| Satisfaction | 21 | 0.37 | 0.28, 0.46 | −0.08, 0.70 | 421.18 | 0.05 | 95.24 | 7405 | 49 | 3R | 0.41 [0.32, 0.49] |

| Effect Size Statistics | Heterogeneity Statistics | Bias Statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlate | k | r | 95% CI | 95% PI | Q | τ2 | I2 | FS | Orwin | Trim/Fill | r [95% CI] |

| PA | 40 | −0.11 | −0.16, −0.07 | −0.38, 0.17 | 503.64 | 0.02 | 92.25 | 2938 | 0 | 11R | −0.05 [−0.10, −0.00] |

| NA | 38 | 0.19 | 0.16, 0.24 | −0.05, 0.42 | 418.65 | 0.02 | 91.17 | 2063 | 39 | 8L | 0.15 [0.11, 0.20] |

| Satisfaction | 18 | −0.18 | −0.32, −0.03 | −0.70, 0.46 | 610.75 | 0.10 | 97.21 | 1311 | 16 | 7L | −0.30 [−0.43, −0.17] |

| 17 A | −0.11 | −0.18, −0.04 | −0.39, 0.18 | 116.70 | 0.02 | 86.29 | 436 | 4 | 0 | No change | |

| Relationship | Group | k | r | 95% CI | 95% PI | Q | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC and PA, SAT | Elite | 9 | 0.23 | 0.14, 0.30 | −0.05, 0.48 | ||

| Sub-elite | 55 | 0.34 | 0.29, 0.36 | 0.03, 0.57 | 5.66 | 0.016 | |

| TC and NA | Elite | 10 | −0.09 | −0.14, −0.03 | −0.32, 0.21 | ||

| Sub-elite | 30 | −0.14 | −0.20, −0.09 | −0.40, 0.13 | 1.81 | 0.178 | |

| Elite | 9 A | −0.10 | −0.15, −0.06 | −0.23, 0.02 | |||

| Sub-elite | 30 | −0.14 | −0.20, −0.09 | −0.40, 0.13 | 1.20 | 0.273 | |

| EC and PA, SAT | Elite | 8 | −0.02 | −0.11, 0.07 | −0.29, 0.26 | ||

| Sub-elite | 47 | −0.16 | −0.21, −0.10 | −0.51, 0.25 | 6.21 | 0.013 | |

| Elite | 8 | −0.02 | −0.11, 0.07 | −0.29, 0.26 | |||

| Sub-elite | 46 B | −0.13 | −0.17, −0.08 | −0.40, 0.16 | 4.49 | 0.034 | |

| EC and NA | Elite | 8 | 0.16 | −0.01, 0.32 | −0.14, 0.36 | ||

| Sub-elite | 30 | 0.21 | −0.05, 0.41 | −0.02, 0.42 | 1.63 | 0.202 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lochbaum, M.; Sisneros, C. A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of the Motivational Climate and Hedonic Well-Being Constructs: The Importance of the Athlete Level. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 976-1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14040064

Lochbaum M, Sisneros C. A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of the Motivational Climate and Hedonic Well-Being Constructs: The Importance of the Athlete Level. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2024; 14(4):976-1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleLochbaum, Marc, and Cassandra Sisneros. 2024. "A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of the Motivational Climate and Hedonic Well-Being Constructs: The Importance of the Athlete Level" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 14, no. 4: 976-1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14040064

APA StyleLochbaum, M., & Sisneros, C. (2024). A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis of the Motivational Climate and Hedonic Well-Being Constructs: The Importance of the Athlete Level. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(4), 976-1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14040064