Equipping Youth to Think and Act Responsibly: The Effectiveness of the “EQUIP for Educators” Program on Youths’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Towards a Cognitive-Behavioral Program for Preventing and Counteracting School-Bullying: The “EQUIP for Educators”

1.2. Empirical Evidence Supporting the Effectiveness of the “EQUIP” Program

1.3. “Why” and “for Whom” School-Based Anti-Bullying Interventions Could Work Better?

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design and Procedure

2.3. Adaptation of the EfE Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Bullying Perpetration

2.5.2. Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions (CDs)

2.5.3. Environmental Sensitivity

2.6. Analytic Strategy

2.6.1. Preliminary Analyses

2.6.2. The Effectiveness of the EfE Program: The Moderated Mediational Model

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses: Attrition Rates and Missing Data Analysis

3.2. Baseline Equivalence: Comparison between Control and Experimental Group before EfE Intervention

3.3. Correlations between Study’s Variables

3.4. Moderated-Mediational Process Model: Testing the Direct, Indirect, and Conditional Effects of EfE Program

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olweus, D. Bullying in School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in Schools: The State of Knowledge and Effective Interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.Κ.; Monks, C.Ρ. Concepts of Bullying: Developmental and Cultural Aspects. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2008, 20, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenio, W.F.; Lemerise, E.A. Aggression and Moral Development: Integrating Social Information Processing and Moral Domain Models. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, G.; Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G. The Mediating Role of Domain Judgement in the Relation between the Big Five and Bullying Behaviours. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 90, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodkin, P.C.; Espelage, D.L.; Hanish, L.D. A Relational Framework for Understanding Bullying: Developmental Antecedents and Outcomes. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Espelage, D.L. A Review of Research on Bullying and Peer Victimization in School: An Ecological System Analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holfeld, B.; Mishna, F. Longitudinal Associations in Youth Involvement as Victimized, Bullying, or Witnessing Cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D.; Long, J.D. A Longitudinal Study of Bullying, Dominance, and Victimization during the Transition from Primary School through Secondary School. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 20, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourander, A.; Helstelä, L.; Helenius, H.; Piha, J. Persistence of Bullying from Childhood to Adolescence—a Longitudinal 8-Year Follow-up Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2000, 24, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, S.; Ttofi, M.M.; Eisner, M.; Gaffney, H. Weapon Carrying in and out of School among Pure Bullies, Pure Victims and Bully-Victims: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Studies. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2017, 33, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrington, D.P.; Loeber, R.; Stallings, R.; Ttofi, M.M. Bullying Perpetration and Victimization as Predictors of Delinquency and Depression in the Pittsburgh Youth Study. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2011, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F.; Loeber, R. Do the Victims of School Bullies Tend to Become Depressed Later in Life? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2011, 3, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F.; Crago, R.V.; Theodorakis, N. School Bullying and Drug Use Later in Life: A Meta-Analytic Investigation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2016, 31, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valdebenito, S.; Ttofi, M.; Eisner, M. Prevalence Rates of Drug Use among School Bullies and Victims: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fry, D.; Fang, X.; Elliott, S.; Casey, T.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Florian, L.; McCluskey, G. The Relationships between Violence in Childhood and Educational Outcomes: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 75, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaffney, H.; Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. Examining the Effectiveness of School-Bullying Intervention Programs Globally: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P. Effectiveness of School-Based Programs to Reduce Bullying: A Systematic and Meta-Analytic Review. J. Exp. Criminol. 2011, 7, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärnä, A.; Voeten, M.; Little, T.D.; Alanen, E.; Poskiparta, E.; Salmivalli, C. Effectiveness of the KiVa Antibullying Program: Grades 1–3 and 7–9. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E. KiVa Anti-Bullying Program in Italy: Evidence of Effectiveness in a Randomized Control Trial. Prev. Sci. 2016, 17, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E.; Nocentini, A.; Palladino, B.E. Empowering Students against Bullying and Cyberbullying: Evaluation of an Italian Peer-Led Model. Int. J. Conf. Violence 2012, 6, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Palladino, B.E.; Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E. Evidence-Based Intervention against Bullying and Cyberbullying: Evaluation of the NoTrap! Program in Two Independent Trials. Aggress. Behav. 2016, 42, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.K.; Salmivalli, C.; Cowie, H. Effectiveness of School-Based Programs to Reduce Bullying: A Commentary. J. Exp. Criminol. 2012, 8, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragone, M.; Esposito, C.; De Angelis, G.; Affuso, G.; Bacchini, D. Pathways Linking Exposure to Community Violence, Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration: A Three-Wave Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esposito, C.; Spadari, E.M.; Caravita, S.C.S.; Bacchini, D. Profiles of Community Violence Exposure, Moral Disengagement, and Bullying Perpetration: Evidence from a Sample of Italian Adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 5887–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fite, P.J.; Cooley, J.L.; Williford, A. Components of Evidence-Based Interventions for Bullying and Peer Victimization. In Handbook of Evidence-Based Therapies for Children and Adolescents; Steele, R.G., Roberts, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- DiBiase, A.M.; Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.B.; Spring, B. EQUIP for Educators: Teaching Youth (Grades 5-8) to Think and Act Responsibly; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pluess, M. Individual Differences in Environmental Sensitivity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2015, 9, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluess, M.; Belsky, J. Vantage Sensitivity: Individual Differences in Response to Positive Experiences. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E.; Pluess, M. The Personality Trait of Environmental Sensitivity Predicts Children’s Positive Response to School-Based Antibullying Intervention. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 6, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBiase, A.M.; Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.B. The EQUIP for Educators Program. Reclaiming Child. Youth 2011, 20, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Hollin, C.R.; Palmer, E.J. Cognitive Skills Programmes for Offenders. Psychol. Crime Law 2009, 15, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landenberger, N.A.; Lipsey, M.W. The Positive Effects of Cognitive–Behavioral Programs for Offenders: A Meta-Analysis of Factors Associated with Effective Treatment. J. Exp. Criminol. 2005, 1, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, F.S.; Lipton, D.S.; Cleland, C.M.; Yee, D.S. The Effects of Behavioral/Cognitive-Behavioral Programs on Recidivism. Crime Delinq. 2002, 48, 476–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.J.; Lipsey, M.W.; Derzon, J.H. The Effects of School-Based Intervention Programs on Aggressive Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, L.; Skrzypiec, G.; Wadham, B. Thinking Patterns, Victimisation and Bullying among Adolescents in a South Australian Metropolitan Secondary School. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2014, 19, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, F.; Brugman, D.; Boom, J.; Koops, W. Effects of EQUIP for Educators on Students’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions, Moral Judgment, and Antisocial Behavior. J. Res. Character Educ. 2010, 8, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Milkman, H.B.; Wanberg, K.W. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment: A Review and Discussion for Corrections Professionals; US Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, B.; Gibbs, J.C. Aggression Replacement Training: A Comprehensive Intervention for Aggressive Youth, 3rd ed.; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-87822-637-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman, J.E.; Wells, K.C. The Coping Power Program at the Middle-School Transition: Universal and Indicated Prevention Effects. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2002, 16, S40–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.B.; Goldstein, A.P. The EQUIP Program: Teaching Youth to Think and Act Responsibly through a Peer-Helping Approach; Reserch Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hardoni, Y.; Neherta, M.; Sarfika, R. Reducing Aggressive Behavior of Adolescent with Using the Aggression Replacement Training. J. Endur. 2019, 4, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, P.; Milone, A.; Manfredi, A.; Polidori, L.; Ruglioni, L.; Lambruschi, F.; Masi, G.; Lochman, J.E. Evaluation of Improvement in Externalizing Behaviors and Callous-Unemotional Traits in Children with Disruptive Behavior Disorder: A 1-Year Follow Up Clinic-Based Study. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2017, 44, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.B.; Barriga, A.Q.; Liau, A.K. Developing the Helping Skills and Prosocial Motivation of Aggressive Adolescents in Peer Group Programs. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1996, 1, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.C. Moral Development and Reality: Beyond the Theories of Kohlberg, Hoffman, and Haidt, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nas, C.N.; Brugman, D.; Koops, W. Effects of the EQUIP Programme on the Moral Judgement, Cognitive Distortions, and Social Skills of Juvenile Delinquents. Psychol. Crime Law 2005, 11, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.; Liau, A.K. The How I Think Questionnaire Manual; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, G.B.; Gibbs, J.C.; Goldstein, A.P. The EQUIP Implementation Guide: Teaching Youth to Think and Act Responsibly through a Peer-Helping Approach; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, N.R.; Dodge, K.A. A Review and Reformulation of Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Children’s Social Adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Morrison, E.M.; Liau, A.K.; Gibbs, J.C. Moral Cognition: Explaining the Gender Difference in Antisocial Behavior. Merrill. Palmer. Q. 2001, 47, 532–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Gibbs, J.C. Measuring Cognitive Distortion in Antisocial Youth: Development and Preliminary Validation of the “How I Think” Questionnaire. Aggress. Behav. 1996, 22, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, G.; Matza, D. Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.C. Sociomoral Developmental Delay and Cognitive Distortion: Implications for the Treatment of Antisocial Youth. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development; Kurtiness, W., Gewirtz, J., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; Volume 3, pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T.; Hymel, S. Moral Disengagement among Children and Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review of Links to Aggressive Behavior. Aggress. Behav. 2014, 40, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Social Cognitive Theory. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 1: Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 101–123. ISBN 978-0-13-815614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brugman, D. Towards a Better Understanding of the Individual, Dynamic, Criminogenic Factors Underlying Successful Outcomes of Cognitive Behavioural Programs Like EQUIP; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, L.W.; Gibbs, J.C.; Fuller, D. Evaluation of a Multi-Component Group Treatment Program for Juvenile Delinquents. Aggress. Behav. 1993, 19, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, R.S.; Gibbs, J.C. Responsible Adult Culture (RAC): Cognitive and Behavioral Changes at a Community-Based Correctional Facility. J. Res. Character Educ. 2010, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liau, A.K.; Shively, R.; Horn, M.; Landau, J.; Barriga, A.; Gibbs, J.C. Effects of Psychoeducation for Offenders in a Community Correctional Facility. J. Community Psychol. 2004, 32, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugman, D.; Bink, M.D. Effects of the EQUIP Peer Intervention Program on Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and Recidivism among Delinquent Male Adolescents. Psychol. Crime Law 2011, 17, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meulen, K.; Granizo, L.; del Barrio, C. Using EQUIP for Educators to Prevent Peer Victimization in Secondary School. J. Res. Character Educ. 2010, 8, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Science, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen, K.; Granizo, L.; del Barrio, C.; de Dios, M.J. El Programa EQUIPAR Para Educadores: Sus Efectos En El Pensamiento y La Conducta Social. [The EQUIP Program for Educators: Its Effects on Cognition and Social Behavior.]. Pensam. Psicológico 2019, 17, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, M. No Effects in Independent Prevention Trials: Can We Reject the Cynical View? J. Exp. Criminol. 2009, 5, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. School-Based Programs to Reduce Bullying and Victimization. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2009, 5, i-148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. Bullying as a Predictor of Offending, Violence and Later Life Outcomes. Crim. Behav. Ment. Heal. 2011, 21, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Miguel, C.S.; Kilburn, J.C.; Sanchez, P. The Effectiveness of School-Based Anti-Bullying Programs. Crim. Justice Rev. 2007, 32, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.H.; Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. Successful Bullying Prevention Programs: Influence of Research Design, Implementation Features, and Program Components. Int. J. Conf. Violence 2012, 6, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Merrell, K.W.; Gueldner, B.A.; Ross, S.W.; Isava, D.M. How Effective Are School Bullying Intervention Programs? A Meta-Analysis of Intervention Research. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2008, 23, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Schneider, B.H.; Smith, P.K.; Ananiadou, K. The Effectiveness of Whole-School Antibullying Programs: A Synthesis of Evaluation Research. School Psych. Rev. 2004, 33, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeman, R.C.; Carroll, A.E. A Systematic Review of School-Based Interventions to Prevent Bullying. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ó Ciardha, C.; Gannon, T.A. The Cognitive Distortions of Child Molesters Are in Need of Treatment. J. Sex. Aggress. 2011, 17, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruna, S.; Copes, H. What Have We Learned from Five Decades of Neutralization Research? Crime Justice 2005, 32, 221–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruna, S.; Mann, R.E. A Fundamental Attribution Error? Rethinking Cognitive Distortions. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2006, 11, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banse, R.; Koppehele-Gossel, J.; Kistemaker, L.M.; Werner, V.A.; Schmidt, A.F. Pro-Criminal Attitudes, Intervention, and Recidivism. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2013, 18, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helmond, P.; Overbeek, G.; Brugman, D.; Gibbs, J.C. A Meta-Analysis on Cognitive Distortions and Externalizing Problem Behavior. Crim. Justice Behav. 2015, 42, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Fong, C.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Espelage, D.L. Declines in Efficacy of Antibullying Programs among Older Adolescents: Theory and a Three-Level Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 37, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, T.; Strohmeier, D.; Spiel, C. Dynamic Change of Aggressive Behavior and Victimization Among Adolescents: Effectiveness of the ViSC Program. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, S90–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, D.; Belsky, D.W.; Crowley, D.M.; Latendresse, S.J.; Aliev, F.; Riley, B.; Sun, C.; Dick, D.M.; Dodge, K.A. Can Genetics Predict Response to Complex Behavioral Interventions? Evidence from a Genetic Analysis of the Fast Track Randomized Control Trial. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2015, 34, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, B.; Lionetti, F.; Pluess, M. Vantage Sensitivity: A Framework for Individual Differences in Response to Psychological Intervention. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pluess, M.; Boniwell, I. Sensory-Processing Sensitivity Predicts Treatment Response to a School-Based Depression Prevention Program: Evidence of Vantage Sensitivity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2015, 82, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Pluess, M. Beyond Diathesis Stress: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 885–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horn, M.; Shively, R.; Gibbs, J.C. EQUIPPED for Life Game; Franklin Learning: Westport, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchini, D.; De Angelis, G.; Affuso, G.; Brugman, D. The Structure of Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2016, 49, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluess, M.; Assary, E.; Lionetti, F.; Lester, K.J.; Krapohl, E.; Aron, E.N.; Aron, A. Environmental Sensitivity in Children: Development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and Identification of Sensitivity Groups. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 0001-690X. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson, D.C.; Cook, T.D.; Gardner, F.E.M.; Gorman-Smith, D.; Howe, G.W.; Sandler, I.N.; Zafft, K.M. Standards of Evidence for Efficacy, Effectiveness, and Scale-up Research in Prevention Science: Next Generation. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 893–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lardén, M.; Melin, L.; Holst, U.; Långström, N. Moral Judgement, Cognitive Distortions and Empathy in Incarcerated Delinquent and Community Control Adolescents. Psychol. Crime Law 2006, 12, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Lagerspetz, K.; Björkqvist, K.; Österman, K.; Kaukiainen, A. Bullying as a Group Process: Participant Roles and Their Relations to Social Status within the Group. Aggress. Behav. 1998, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Wu, E.J.C. EQS 6.1 for Windows User’s Guide; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 1885898037. [Google Scholar]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Thorpe, D.I.; Rentz, J.O. A Measure of Service Quality for Retail Stores: Scale Development and Validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.A.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0471183865. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A. Sensory-Processing Sensitivity and Its Relation to Introversion and Emotionality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A.; Jagiellowicz, J. Sensory Processing Sensitivity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Moyzis, R.; Stern, H.; He, Q.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, B.; Dong, Q. Contributions of Dopamine-Related Genes and Environmental Factors to Highly Sensitive Personality: A Multi-Step Neuronal System-Level Approach. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagiellowicz, J.; Xu, X.; Aron, A.; Aron, E.; Cao, G.; Feng, T.; Weng, X. The Trait of Sensory Processing Sensitivity and Neural Responses to Changes in Visual Scenes. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2011, 6, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Stam, M.A.; van der Schuur, W.A.; Tserkezis, S.; van Vugt, E.S.; Asscher, J.J.; Gibbs, J.C.; Stams, G.J.J.M. The Effectiveness of EQUIP on Sociomoral Development and Recidivism Reduction: A Meta-Analytic Study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 38, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Methodology, Design, and Evaluation in Psychotherapy Research. In Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change; Bergin, A.E., Garfield, S.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 19–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Ryoo, J.H.; Swearer, S.M.; Turner, R.; Goldberg, T.S. Longitudinal Relationships between Bullying and Moral Disengagement among Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchini, D.; Affuso, G.; Aquilar, S. Multiple Forms and Settings of Exposure to Violence and Values. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 3065–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low HSC ≤30% HSC | Medium HSC 30% < HSC ≥ 70% | High HSC >70% HSC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Total sample n = 324 | 64 37.9% | 32 20.6% | 72 42.6% | 70 45.2% | 33 19.5% | 53 34.2% |

| Control group n = 167 | 39 37.1% | 12 19.4% | 49 46.7% | 28 45.2% | 17 16.2% | 22 35.5% |

| Experimental group n = 157 | 25 39.1% | 20 21.5% | 23 35.9% | 42 45.2% | 16 25% | 31 33.3% |

| Measures | EfE Conditions | Gender | School Grade | Groups Differences | Gender Differences | School Grade Differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group (n = 167) | Experimental Group (n = 157) | Males (n = 169) | Females (n = 155) | Middle (n = 141) | High (n = 183) | |||||||

| Means (SDs) | F(1,316) | η2p | F(1,316) | η2p | F(1,316) | η2p | ||||||

| Self-serving CDs | 2.08 (0.75) | 2.09 (0.76) | 2.17 (0.76) | 1.99 (0.74) | 2.09 (0.84) | 2.08 (0.68) | 0.29 | 0.00 | 3.85 * | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Bullying perpetration | 1.36 (0.51) | 1.26 (0.39) | 1.39 (0.53) | 1.24 (0.35) | 1.32 (0.45) | 1.21 (0.33) | 2.10 | 0.01 | 5.99 * | 0.02 | 3.62 | 0.01 |

| Environmental sensitivity | 3.04 (0.86) | 3.12 (0.81) | 2.91 (0.87) | 3.26 (0.76) | 3.01 (0.95) | 3.13 (0.73) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.39 *** | 0.04 | 1.76 | 0.01 |

| Measures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School grade (High) | 1 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.15 |

| 2. T1 Self-serving CDs | 0.06 | 1 | 0.62 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.40 *** |

| 3. T2 Self-serving CDs | 0.16 * | 0.61 *** | 1 | 0.33 *** | 0.46 *** |

| 4. T1 Bullying perpetration | −0.14 | 0.35 *** | 0.30 *** | 1 | 0.52 *** |

| 5. T2 Bullying perpetration | −0.09 | 0.34 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.35 *** | 1 |

| M | - | 2.08 (2.09) | 1.92 (1.78) | 1.36 (1.26) | 1.32 (1.25) |

| SDs | - | 0.75 (0.76) | 0.78 (0.73) | 0.51 (0.39) | 0.55 (0.42) |

| Range | - | 1–6 | 1–5 | ||

| Unique and Interactive Effects | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Self-Serving CDs (T2) | Bullying Perpetration (T2) | |||||

| B | SE | 95% C.I. | B | SE | 95% C.I.s | ||

| EfE conditions (Control vs. Experimental group) | 4.54 | 3.56 | [−2.44, 11.53] | −0.00 | 0.13 | [−0.26, 0.26] | |

| Sensitivity groups (Low vs. Medium HSC) | 3.96 | 3.13 | [−2.18, 10.10] | −0.04 | 0.16 | [−0.34, 0.27] | |

| Sensitivity groups (Low vs. High HSC) | 9.87 * | 3.88 | [2.26, 17.47] | −0.02 | 0.18 | [−0.38, 0.33] | |

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | 1.50 | 1.87 | [−2.18, 5.17] | −0.12 | 0.14 | [−0.40, 0.16] | |

| Experimental group × Medium HSC | −1.62 | 4.78 | [−10.99, 7.75] | - | - | - | |

| Experimental group × High HSC | −16.90 ** | 5.57 | [−27.82, −5.98] | - | - | - | |

| Experimental group × Gender | −4.28 | 2.53 | [−9.24, 0.68] | - | - | - | |

| Medium HSC × Gender | −2.95 | 2.30 | [−7.46, 1.57] | - | - | - | |

| High HSC × Gender | −6.13 * | 2.62 | [−11.26, −0.99] | - | - | - | |

| Experimental group × Medium HSC × Gender | 2.10 | 3.22 | [−4.21, 8.41] | - | - | - | |

| Experimental group × High HSC × Gender | 10.86 ** | 3.59 | [3.82, 17.90] | - | - | - | |

| Self-serving CDs (T2) | - | - | - | 0.06 *** | 0.01 | [0.04, 0.08] | |

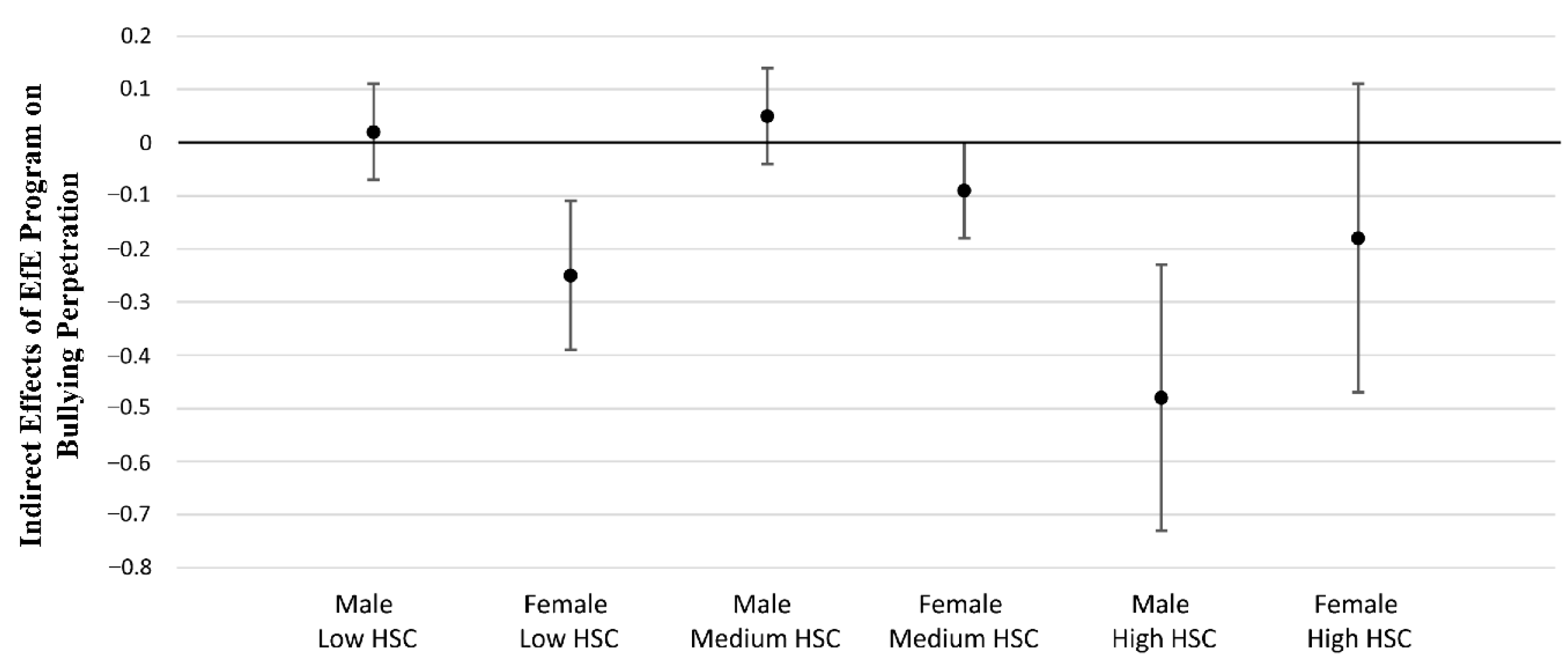

| Conditional Indirect Effects of the EfE Program at Different Values of Gender and Sensitivity Groups (Moderators) | |||||||

| Self-serving CDs (T2–Mediator) | Males with Low HSC | - | - | - | 0.02 | 0.09 | [−0.13, 0.17] |

| Females with Low HSC | - | - | - | −0.25 | 0.14 | [−0.47, 0.03] | |

| Males with Medium HSC | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.09 | [−0.10, 0.19] | |

| Females with Medium HSC | - | - | - | −0.09 | 0.09 | [−0.23, 0.05] | |

| Males with High HSC | - | - | - | −0.48 * | 0.25 | [−0.88, −0.07] | |

| Females with High HSC | - | - | - | −0.18 | 0.29 | [−0.66, 0.30] | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dragone, M.; Esposito, C.; De Angelis, G.; Bacchini, D. Equipping Youth to Think and Act Responsibly: The Effectiveness of the “EQUIP for Educators” Program on Youths’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 814-834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12070060

Dragone M, Esposito C, De Angelis G, Bacchini D. Equipping Youth to Think and Act Responsibly: The Effectiveness of the “EQUIP for Educators” Program on Youths’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2022; 12(7):814-834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12070060

Chicago/Turabian StyleDragone, Mirella, Concetta Esposito, Grazia De Angelis, and Dario Bacchini. 2022. "Equipping Youth to Think and Act Responsibly: The Effectiveness of the “EQUIP for Educators” Program on Youths’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 12, no. 7: 814-834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12070060

APA StyleDragone, M., Esposito, C., De Angelis, G., & Bacchini, D. (2022). Equipping Youth to Think and Act Responsibly: The Effectiveness of the “EQUIP for Educators” Program on Youths’ Self-Serving Cognitive Distortions and School Bullying Perpetration. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 12(7), 814-834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12070060