COVID-19 Limitations on Doodling as a Measure of Burnout

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Feedback on Doodling and COVID-19

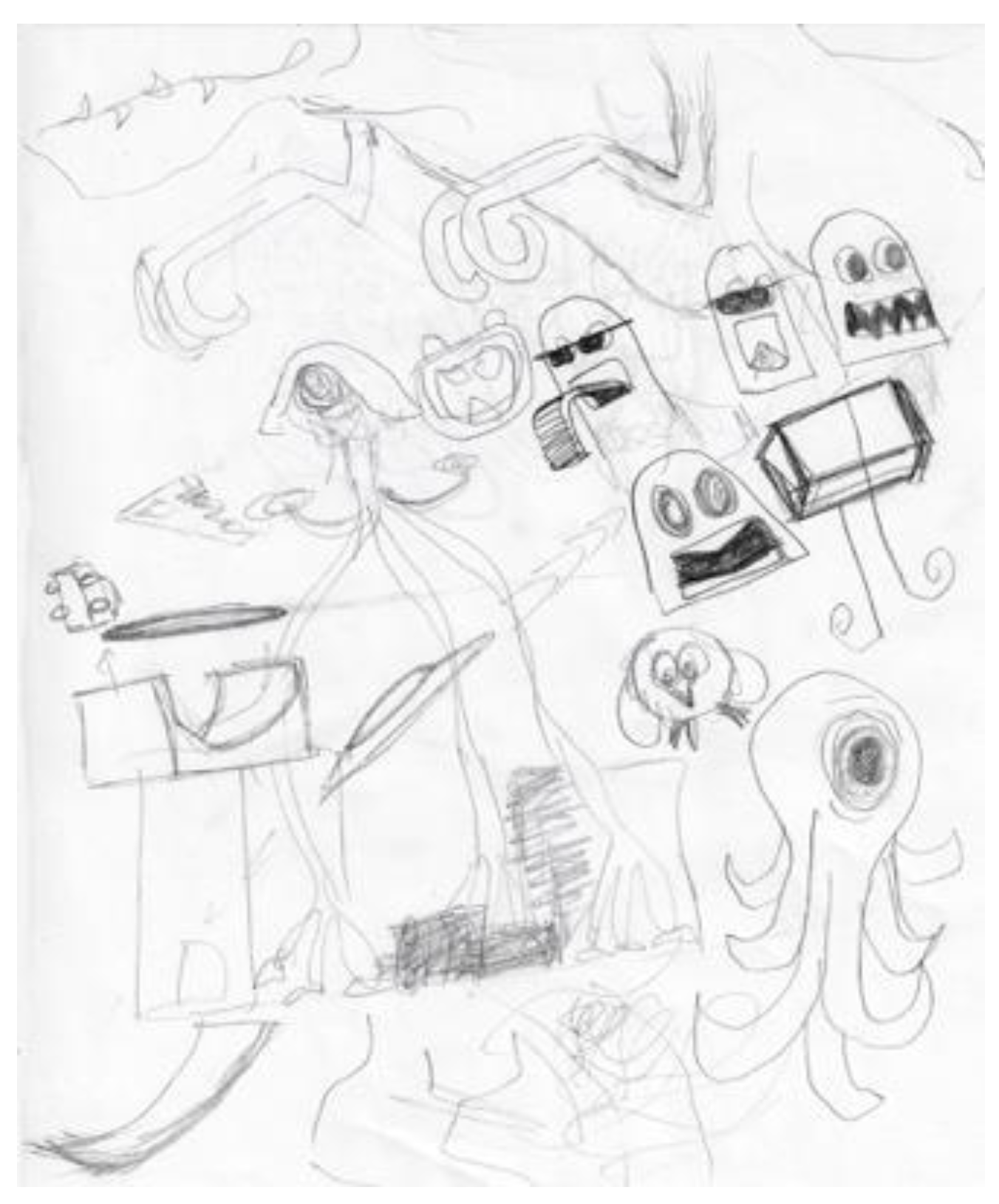

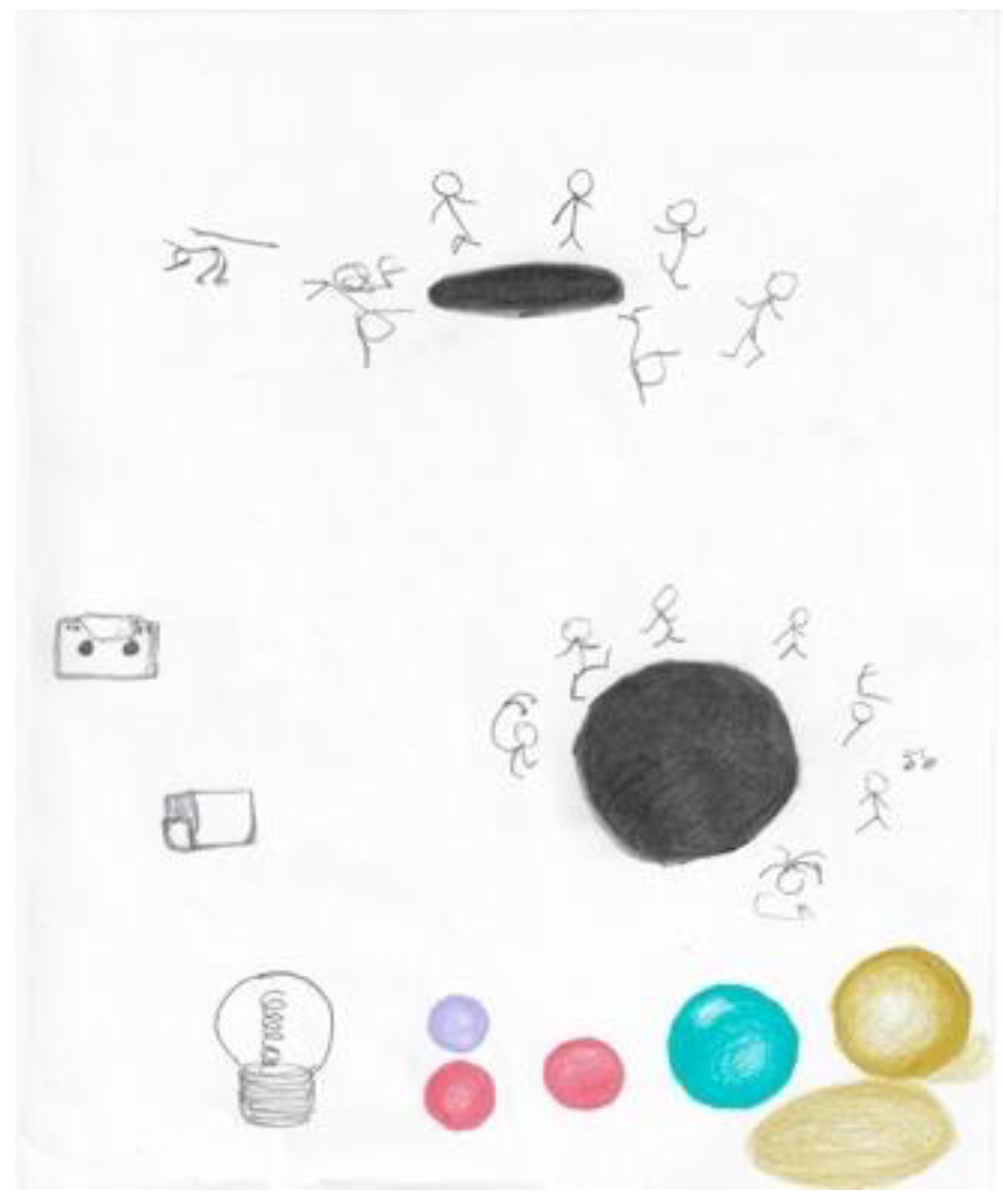

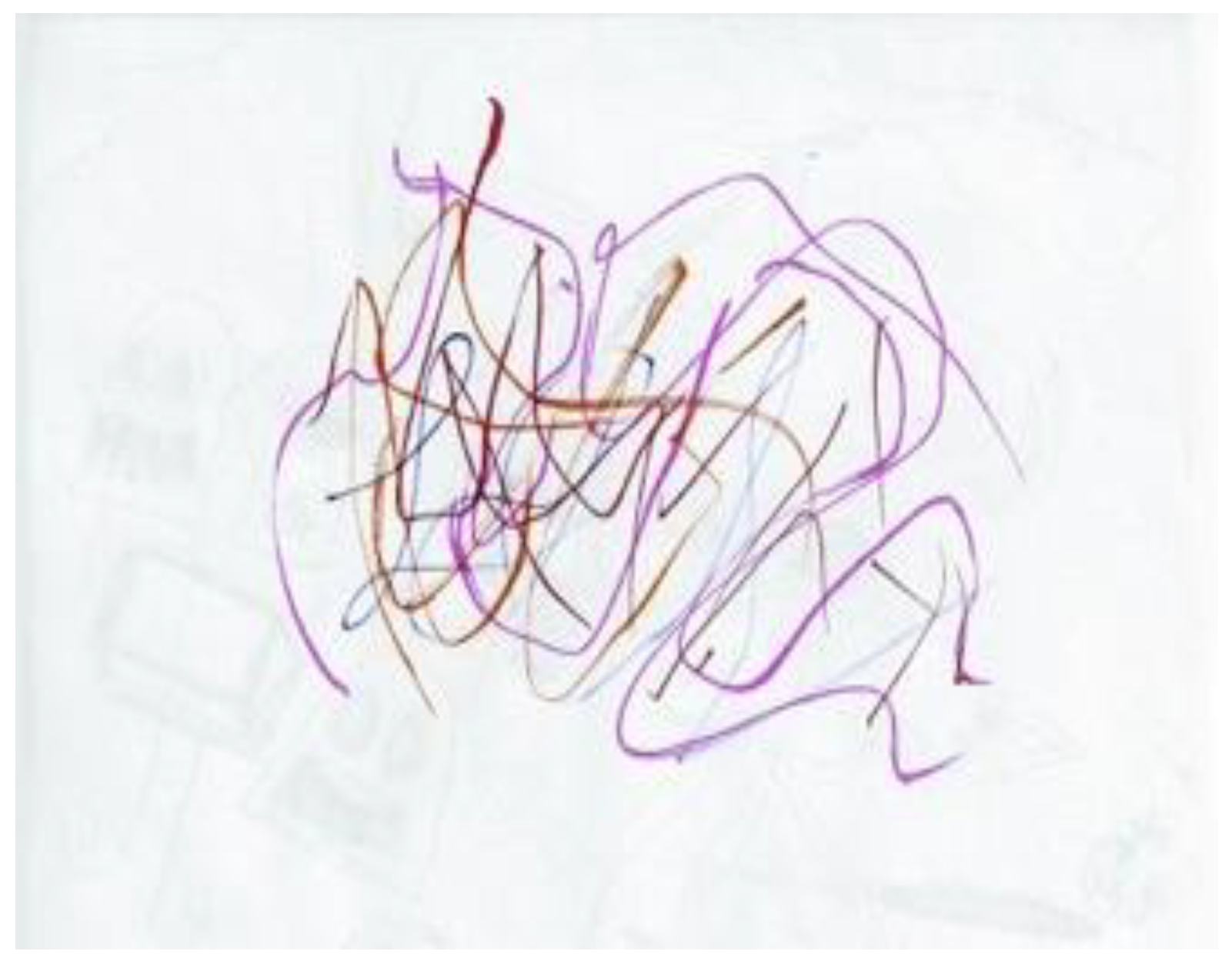

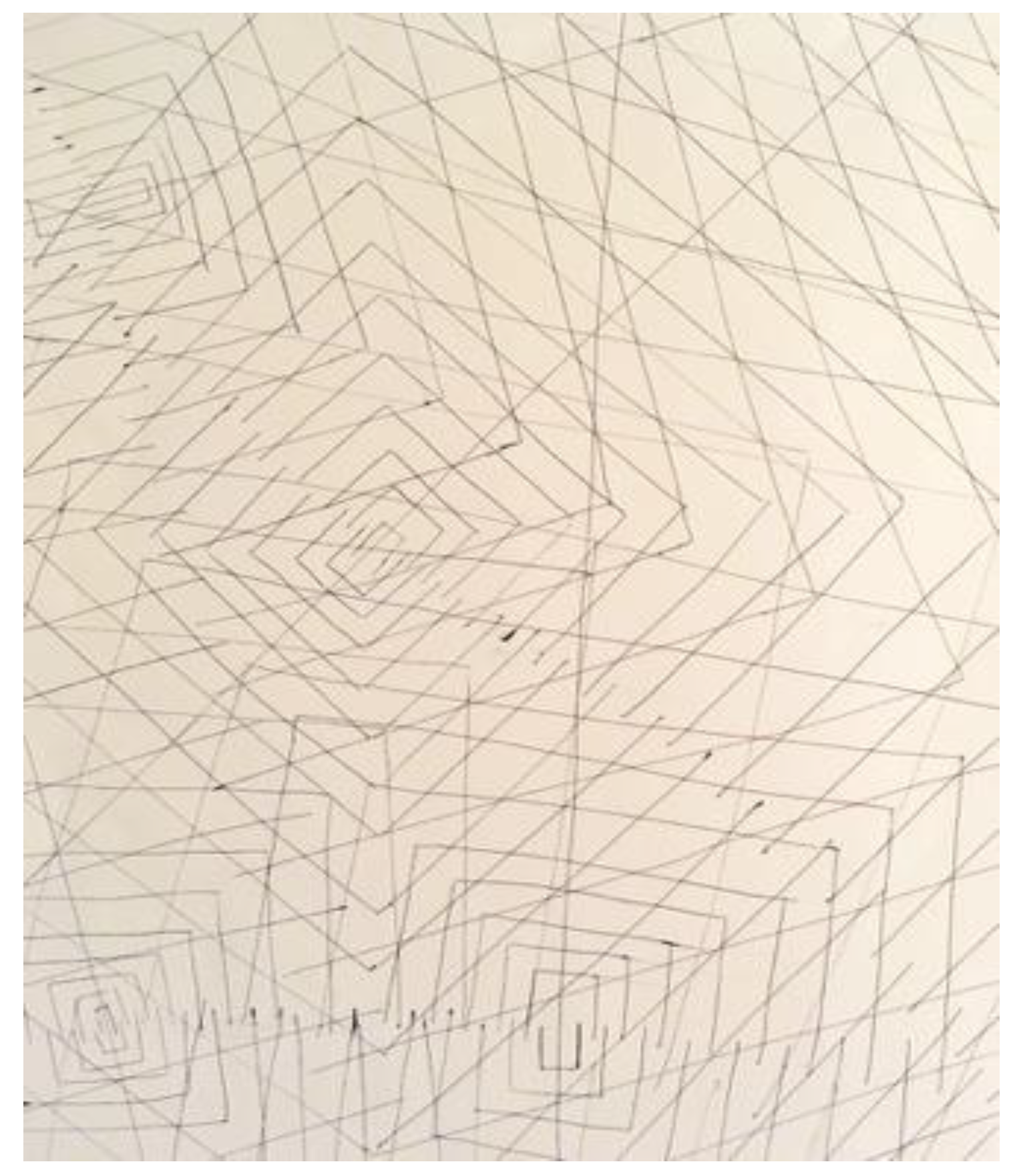

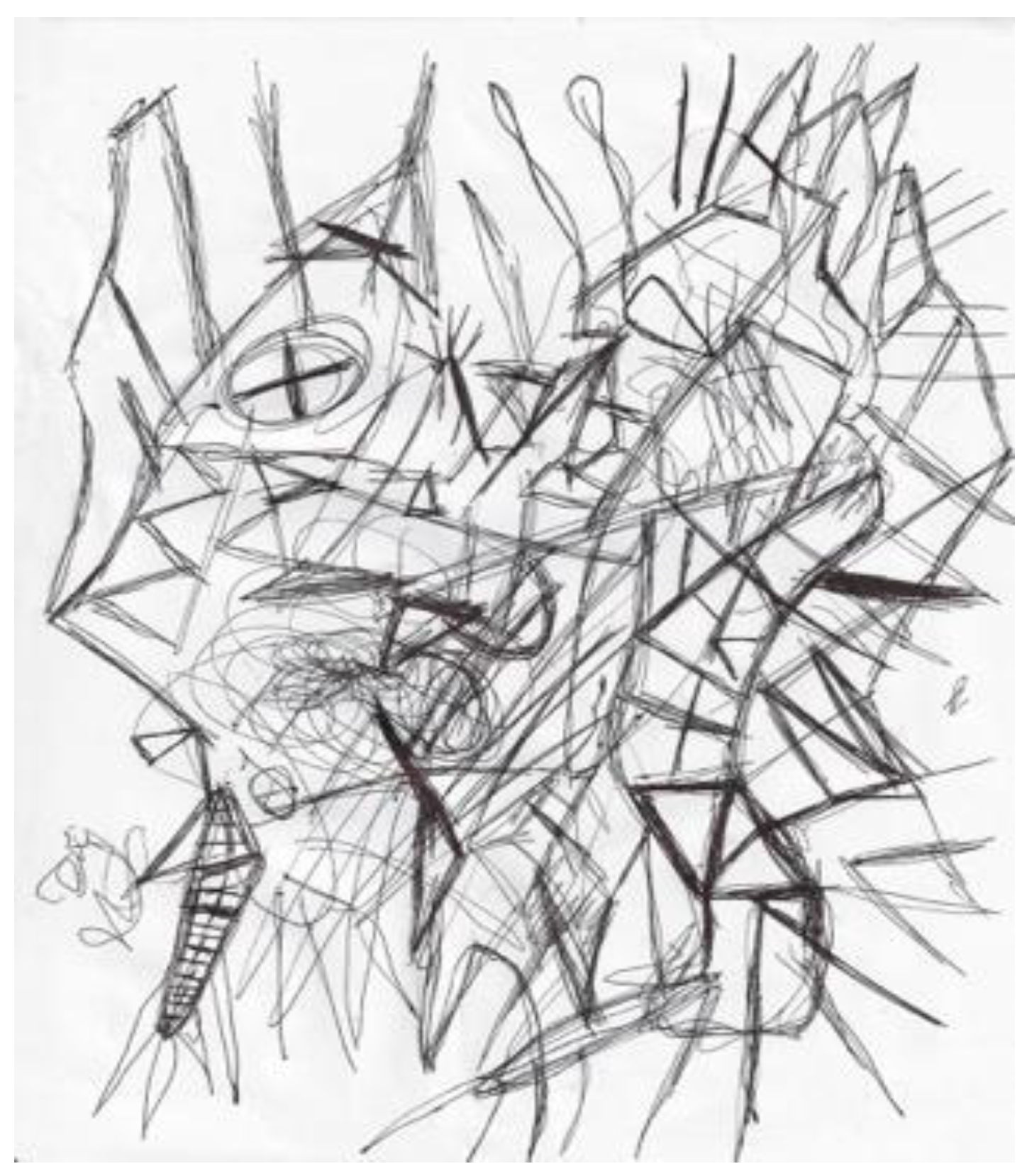

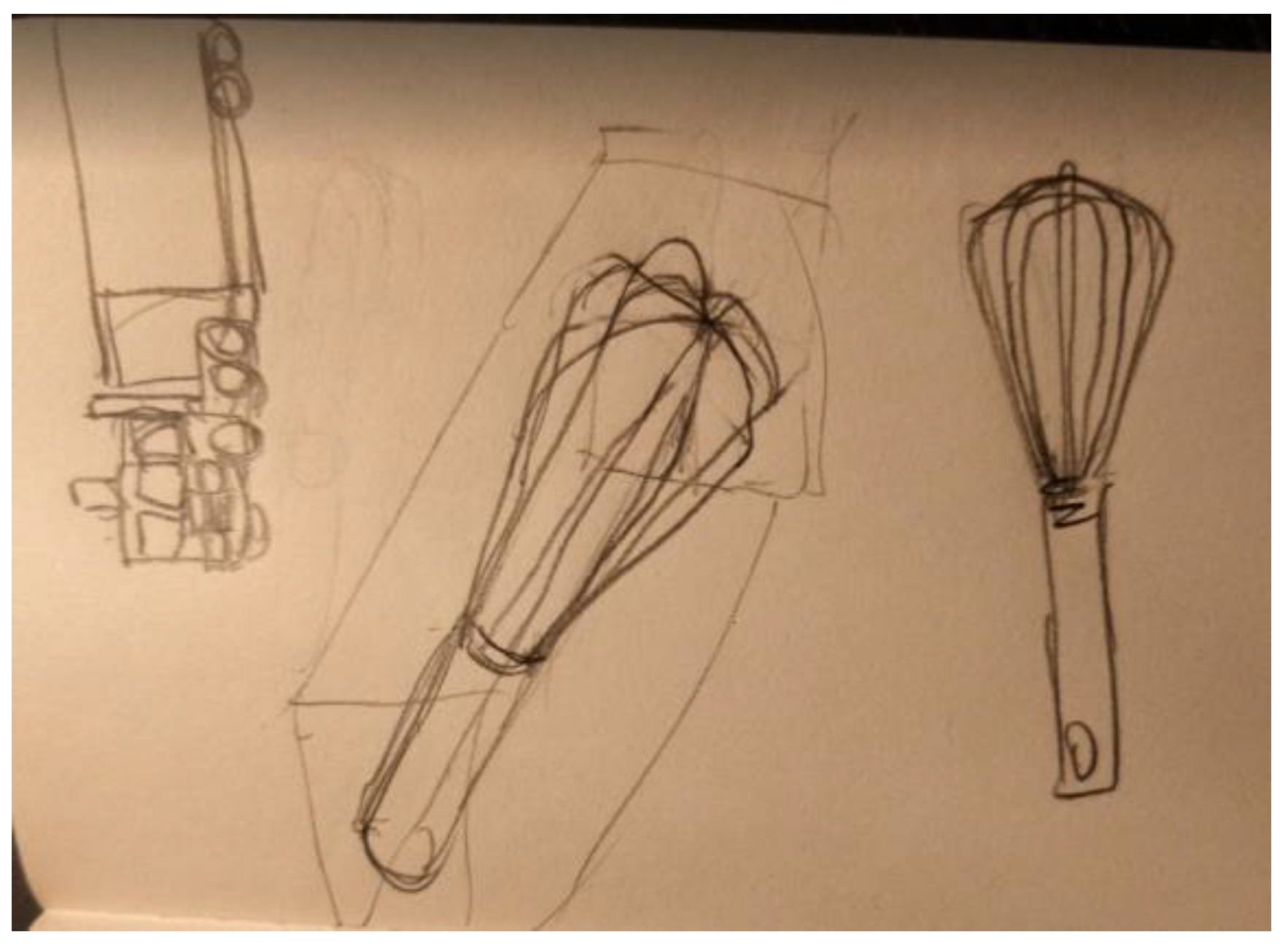

3.2. Pre-COVID-19 Doodling in Participants Reporting Depression and Anxiety

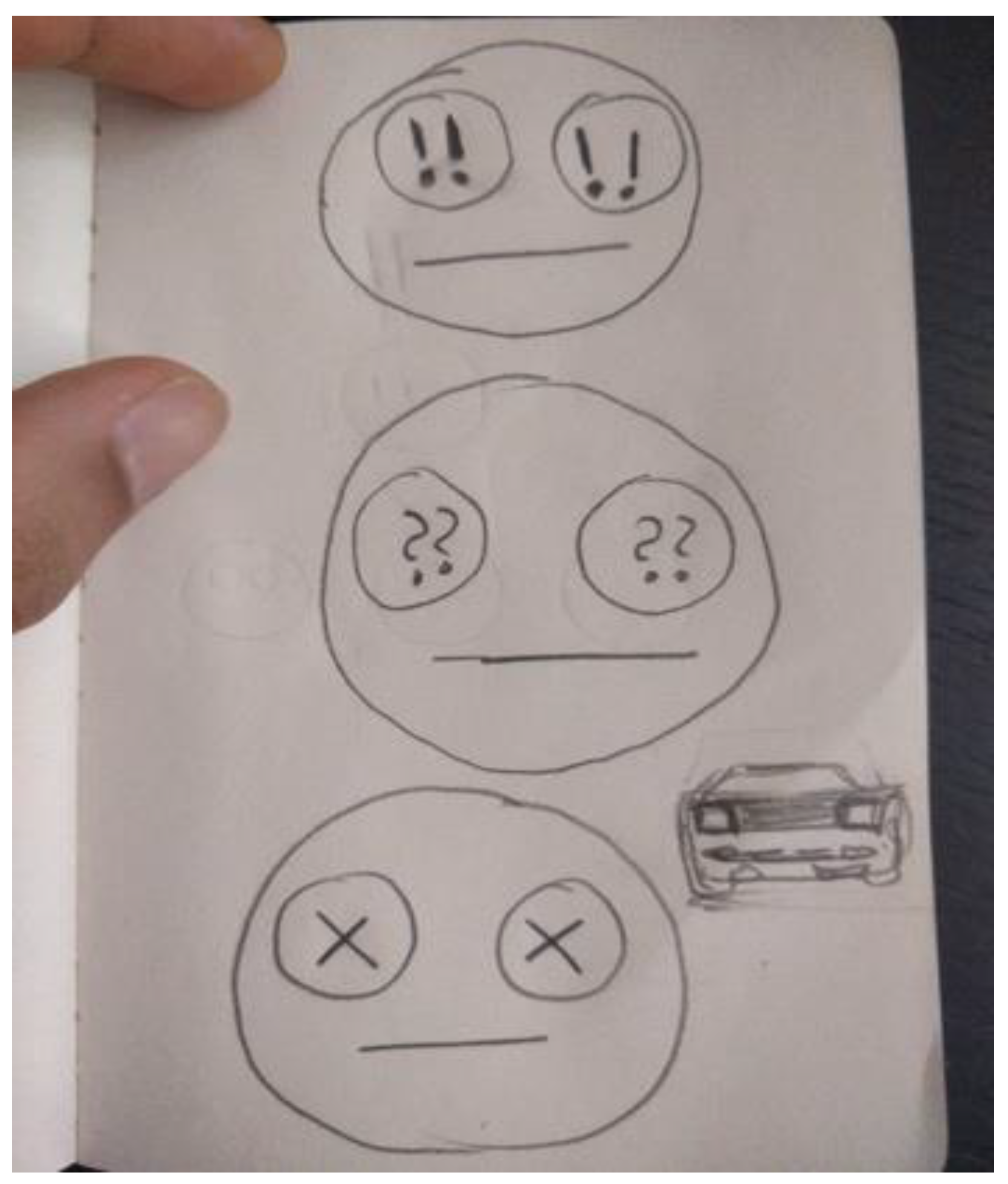

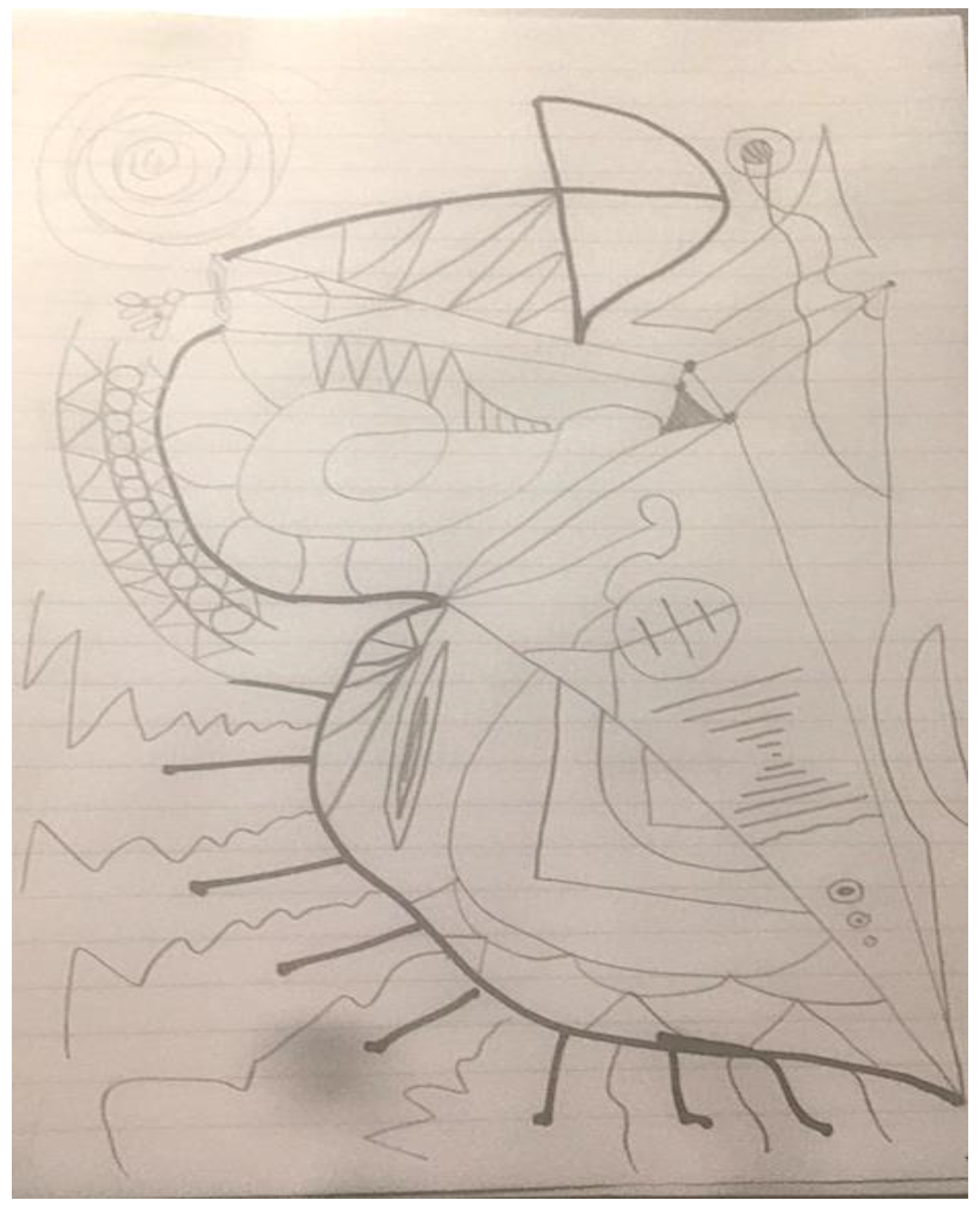

3.3. Doodling of Participants Reporting Depression and Anxiety during COVID-19

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Measuring Burnout

5. Conclusions

Regarding Team Mindfulness

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckleberry-Hunt, J.; Kirkpatrick, H.; Barbera, T. The Problems With Burnout Research. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, B.; Hartman, E.A. Burnout: Summary and Future Research. Hum. Relat. 1982, 35, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Van Dierendonck, D. The construct validity of two burnout measures. J. Organ. Behav. 1993, 14, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; Atkinson, S.; Brown, S.S.; Haslam, R. Anxiety and depression in the workplace: Effects on the individual and organisation (a focus group investigation). J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 88, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsten, M.K.; Uhl-Bien, M.; West, B.J.; Patera, J.L.; McGregor, R. Exploring social constructions of followership: A qualitative study. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xin, H.; Shen, L.; He, J.; Liu, J. The Influence of Individual and Team Mindfulness on Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zellmer-Bruhn, M. Introducing Team Mindfulness and Considering its Safeguard Role Against Conflict Transformation and Social Undermining. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 61, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Weiner, E. (Eds.) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, B. Oodles of Doodles? Doodling Behaviour and Its Implications for Understanding Palaeoarts. Rock Art Res. 2008, 25, 35–43. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aft&AN=505310700&site=ehost-live (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Pillay, S. The “Thinking” Benefits of Doodling; Harvard Health Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-thinking-benefits-of-doodling-2016121510844 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Baweja, P. Doodling: A Positive Creative Leisure Practice. In Positive Sociology of Leisure; Kono, S., Beniwal, A., Baweja, P., Spracklen, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switherland, 2020; pp. 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, G.; Ayaz, H.; Herres, J.; Dieterich-Hartwell, R.; Makwana, B.; Kaiser, D.H.; Nasser, J.A. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy assessment of reward perception based on visual self-expression: Coloring, doodling, and free drawing. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amico, G.; Schaefer, S. No Evidence for Performance Improvements in Episodic Memory Due to Fidgeting, Doodling or a “Neuro-Enhancing” Drink. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2020, 4, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, C. Doodling as a Measure of Burnout in Healthcare Researchers. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2020, 45, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclay, W.S.; Guttmann, E.; Mayer-Gross, W. Spontaneous Drawings as an Approach to Some Problems of Psychopathology. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1938, 31, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Guzman, A.; Pablo, L.A.; Prieto, R.J.; Purificacion, V.N.; Que, J.J.; Quia, P. Understanding the persona of clinical instructors: The use of students’ doodles in nursing research. Nurse Educ. Today 2008, 28, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J. What does doodling do? Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2009, 24, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, G. Doodling and the default network of the brain. Lancet 2011, 378, 1133–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. The Negative Effect of Doodling on Visual Recall Task Performance. Uni. Brit. Colum. Undergrad. J. Pysch. 2012, 1. Available online: https://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/ubcujp/article/view/2526 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Siagto-Wakat, G. Doodling the Nerves: Surfacing Language Anxiety Experiences in an English Language Classroom. RELC J. 2017, 48, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadayon, M.; Afhami, R. How Does Doodling Effects on Students Learning as an Artistic Method? Kimiya-ye-Honar 2015, 4, 86–97. Available online: http://kimiahonar.ir/article-1-598-en.html (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Tadayon, M.; Afhami, R. Doodling Effects on Junior High School Students’ Learning. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2017, 36, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, J.B.; Cohen, J.L.; Marchand, G.C. The effects of doodling on recall ability. Psychol. Thought 2017, 10, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burton, B.N.; Baxter, M.F. The Effects of the Leisure Activity of Coloring on Post-Test Anxiety in Graduate Level Occupational Therapy Students. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, M.E.; Wammes, J.D.; Fernandes, M.A. Comparing the Influence of Doodling, Drawing, and Writing at Encoding on Memory. Can. J. Exper. Psychol 2019, 73, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.P.; Kashyap, N. Does Doodling Effect Performance: Comparison Across Retrieval Strategies. Psychol. Stud. 2015, 60, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, S.; Koole, W.; Chaskalson, M.; Tamdjidi, C.; West, M. Running too far ahead? Towards a broader understanding of mindfulness in organisations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, D. Understanding the Original of Paleoart: The Neurovisual Resonance Theory of Brain Functioning. Paleoanthropology 2006, 2006, 54–67. Available online: https://paleoanthro.org/static/journal/content/PA20060054.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Harrod, J.B. Bhimbetka Glyphs. In Exploring The Mind of Ancient Man: Festschrift to Robert G. Bednarik; Reddy, P.C., Ed.; Research India Press: New Delhi, India, 2007; pp. 317–330. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/22408718/The_Bhimbetka_Glyphs_2007_ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- McDonald, D.; Vines, R. Flipping Advanced Organizers Into an Individualized Meaning-Making Learning Process Through Sketching. Teach. Artist. J. 2019, 17, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Solmaz, F. COVID-19 burnout, COVID-19 stress and resilience: Initial psychometric properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Stud. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferry, A.V.; Wereski, R.; Strachan, F.E.; Mills, N.L. Predictors of UK healthcare worker burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM J. Assoc. Phys. 2021, 114, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uong, A.M.; Cabana, M.D.; Serwint, J.R.; Bernstein, C.A.; Schulte, E.E. Changes in Pediatric Faculty Burnout During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hosp. Pediatr. 2021, 11, e364–e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumiller, M.; Dresel, M. Researchers’ achievement goals: Prevalence, structure, and associations with job burnout/engagement and professional learning. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, V.; VanYperen, N. How to conduct research on burnout: Advantages and disadvantages of a unidimensional approach in burnout research. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 16i–20i. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work: An Integrative Review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Response to Doodling Question | Doodles Shared | Response to COVID-19 Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | On the days that I felt like I had an idea, the doodles were helpful. But sometimes I went to doodle and I froze because I wasn’t really sure what to draw. In these moments, it was more beneficial to think about the conversation happening and not focus on the doodles. | 5 | This group was a great way to network as a student new to research, especially with all of the restrictions placed by COVID-19. This school year has been very isolating and I have not been able to go to the campus as a student yet. It was nice to have a platform where I could meet new people who I would have otherwise never have connected with. |

| 2 | I think it helps, but it helps even more when we are doodling alongside others in the same room. However, I did not doodle much this time around and I will get to it for the next year. | 1 | I reminisce about the times before when we would be able to meet at Mt Sinai, especially where there’s some special touch to being with one another in person. |

| 3 | I stopped doodling years ago as I came to perceive it as a sign of not paying attention. Learned that it is a great way to gauge my mood and thoughts that I am bringing to the session. | 16 | My only experience with group was during COVID. Doing the group online supported my ability to attend as no travel and also to spend time reflecting during the sessions. Also, anxieties related to speaking in groups was not an area I was concerned with. Facebook as a platform was a bit challenging as refreshing my screen did not always bring updated postings. Also, wonder if a more dynamic platform would be considered or tips for navigating the platform. |

| 4 | I love doodling, it’s one of the best parts of the HeNReG. People aren’t encouraged to draw in everyday life and I think this is a great way to encourage it. | 8 | Although I miss in person meeting, online participation was done very well by [the facilitator]. The flexibility of meeting online is also a positive. |

| 5 | I believe that it gave me something to do during the two hour period of the meeting while waiting for people to participate online. | 28 | I was surprised that working entirely online affected the ability of people to participate in doodling to such a great extent. As well, I hadn’t anticipated that so few people would ask others questions. |

| 6 | Love it! Especially in person, as doodling has always helped me feel calmer and more present in group discussions. | 7 | Having participated in HeNReG both in person and online, I have to note that it has been much more difficult to engage online, likely due to accumulated tiredness from all work and social activities being in a virtual format since the beginning of the pandemic. But I did appreciate [the facilitator’s] accommodative format of not running HeNReG through a video call platform but rather having a set time for online Facebook discussion. |

| 7 | I like it a lot but I think it’s easier to do the doodling in-person than online | 2 | I like the online environment especially because I don’t need to travel to the room. |

| 8 | Great aspect—I would like to take advantage of this more in the future | 0 | Unfortunately, due to strains of COVID on my day to day to job, my capacity to actively participate this term was limited. I hope in future sessions, I can more actively participate |

| 9 | Gives me some time to think a while and sketch messy ideas in my mind | 0 | Hope COVID 19 ends soon |

| 10 | I love the doodling aspect, because it helps me as a fidgety person | 0 | I think the way of handling the entirely online group was done very well! |

| 11 | I get carried away with doodling sometimes | 4 | I like the flexibility and structure of the meetings online, which allows me to read and reflect on the responses anytime of the day. |

| 12 | I like it. It’s nice when I get to do it | 4 | no |

| 13 | It improves one’s thinking capability. | 0 | My experience was fantastic. I enjoyed the course of the programme. It was a period of learning for a young and burgeoning researcher like me. |

| 14 | I have not participated in this part | 0 | Wish I could engage more and more actively |

| 15 | Some of them look super amazing! | 0 | I have been remote before already so not too different. Would be good if the time can be after work hours though. Might be nice to have an interactive call section to share and answer questions? |

| 16 | I do not doodle | 0 | Not now |

| 17 | Relieving | 2 (photos) | It got me active engaged during the period of strict lockdown |

| 18 | Good | 1 (photo) | Connection with other co-workers is important |

| 19 | Not a member second term when question asked | 5 | I appreciated being able to participate virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic. I wish there could have been a little more interaction, perhaps using Teams or Zoom? (fall 2020 response) |

| 20 | Did not return feedback form | 2 (photos) | Did not return feedback form |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nash, C. COVID-19 Limitations on Doodling as a Measure of Burnout. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1688-1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040118

Nash C. COVID-19 Limitations on Doodling as a Measure of Burnout. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2021; 11(4):1688-1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040118

Chicago/Turabian StyleNash, Carol. 2021. "COVID-19 Limitations on Doodling as a Measure of Burnout" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11, no. 4: 1688-1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040118

APA StyleNash, C. (2021). COVID-19 Limitations on Doodling as a Measure of Burnout. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(4), 1688-1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040118