Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to describe COVID-19 health literacy, coping strategies and perception of COVID-19 containment measures among community members in a Southwestern state in Nigeria. Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional design was used to enroll 691 respondents from households in Akure, Ondo state using a multi-stage sampling technique. Data were collected using an interviewer- administered questionnaire between 1st and 9th October, 2020. Bivariate Chi-square tests were conducted on respondents’ COVID-19 health literacy while multivariate logistic analysis was performed on significant variables. Statistical significance levels were set at p<0.05. Results: Respondents’ mean age was 29.93±10.66 years, 352 (50.9%) were males. Also, 292 (49.7%) had high levels of trust in the World Health Organization regarding COVID-19 information, and 31 (33.3%) in the first wealth quintile had good health literacy (χ2=10.459, p=0.033). Respondents below 20 years were twice more likely to have good COVID-19 health literacy (OR=2.304, 95%CI=1.316-4.034, p=0.004). Also, respondents aged 21-29 years were three times more likely to have good COVID-19 health literacy (OR=2.587, 95%CI=1.559-4.293, p≤0.001). Conclusions: Available media platforms should be actively engaged by the national government to ensure that community members especially the rich are equipped with good health literacy.

Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, health literacy is the ability to which individuals obtain, understand, and apply health-related knowledge to in form health decisions and actions both for oneself and others [1]. Regarding COVID-19 health literacy, the effectiveness of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp have been communicated [2,3]. In addition, the traditional media i.e., radio and television have been frequently used for broadcasting COVID-19 risk information and preventive practices through which survival can be assured during the COVID-19 pandemic period [2]. Despite the profound benefits offered by these channels in modelling healthy behavior, the difficulty in understanding COVID-19-related information across these sources may result in poor COVID-19 health literacy and low levels of trust in recommended measures [4]. Findings from literature reveal parental emotional responses regarding prolonged school closure as one of the implications of the alarming news of the increase in COVID-19 cases [5]. With sufficient trust in sources of COVID-19 information sequel to adequate understanding, an individual identifies his vulnerability to COVID-19 and can adopt recommended safety measures required to reduce the rising trend in COVID-19 cases.

An increase in COVID-19 cases have been reported globally. As of 6th October 2021, nearly 237 million COVID-19 cases and nearly 5 million deaths have been reported. Of this global total, Nigeria accounts for 206,920 (≈0.1%) cases and 2,740 (≈0.1%) deaths [6]. In Nigeria, nationwide public health measures such as physical distancing, mandatory hand hygiene in public places, and compulsory use of face masks have been implemented to contain COVID-19 [6]. However, these measures have been accosted by different perceptions among members of the population. Individual perception has been described as a critical factor for the adoption of safety precautions necessary for infection prevention [7]. This therefore suggests that perception forms the bedrock for implementing risk aversion measures. In the COVID-19 context, sequel to the knowledge that non- pharmaceutical public health measures considerably reduced the risk of being infected with SARS-CoV-2, the enumerated safety procedures were advised by the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC) [7].

Research conducted during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ibadan, Nigeria revealed high levels of misconceptions surrounding COVID-19 among community members. These included COVID-19 attributed as a disease of well-to-do persons and politicians, as well as a political strategy for corruption [2]. However, despite these trending fallacies, social distancing measures were frequently practiced in public places [2]. In addition, practices such as wearing of face masks, cough etiquette, and avoidance of crowded spaces were reported from a web-based study conducted among the Nigerian population [8]. Evidence from these literatures therefore validate positive perception of recommended COVID-19 preventive measures in many Nigerian communities.

Coping strategies have been described as specific efforts (mostly behavioral) employed by people to tolerate stressful events [9,10]. The implementation of specific coping strategies includes a number of steps; namely i) acceptance or refusal of the existence of the stressful event; ii) making plans to overcome the stress or giving up on stress-reducing efforts; and iii) drawing lessons from the stressful event or strengthening stressful feelings [9]. Either of these coping responses are triggered when unplanned stressful events occur, and in fact, the COVID-19 outbreak has been stressful both for the young and old. The constellation of different stressors (economic, educational, physical, and psychological) prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic has therefore necessitated different coping mechanisms [9]. In many instances, the available sources of information have influenced the coping strategies adopted by many individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A paucity of information currently exists on the perception of community members regarding the COVID-19 containment measures in Nigeria, and the coping strategies associated with the COVID-19 stressor. Thus, a study of this regard is urgently needed to identify strategies for healthy coping during epidemics or pandemics to ensure a high level of national preparedness. This study therefore aimed to describe COVID-19 health literacy, coping strategies and perception of COVID-19 containment measures among community members in a Southwestern state in Nigeria.

Methods

Study design and study setting

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in specific urban and rural communities in Ondo State. Ondo State is located is one of the southwestern states in Nigeria and has its administrative headquarters in Akure, the capital city. Ondo State is bounded northward by Kwara and Kogi states, eastward by Edo state, westward by Osun and Ogun States, and southward by the Atlantic Ocean [10]. The lingua franca in Ondo State as other parts of Nigeria is English language, while Yoruba language is frequently used for informal communication. The economy of Ondo State is driven by petroleum, cocoa production, and asphalt mining [11]. Ondo State is one of the states with the leading COVID-19 reports in Nigeria. As of the 6th October, 2021, 4,498 COVID-19 cases and 153 COVID-19 deaths had been recorded in Ondo state [11].

Study population

From each household, we enrolled all individuals aged 15 years and above. Persons below 15 years were excluded from the study due to ethical issues such as assent and parental consent required, which may not be currently available. All community members who were willing to participate in the study were enlisted to do so. Prior to the administration of the questionnaires, verbal consent was individually sought from each respondent, and data collection commenced after consent was obtained.

Sample size determination

Sample size for this study was determined by the Leslie Kish formula for calculating sample size for single proportion:

n= (Za)2 * p(1-p)/d2

where,

n=minimum desired sample size

Za=standard normal deviation at 99% confidence interval (2.507).

p=50%

d=degree of accuracy (precision) set at 5%. The minimum sample size was 628. Overall, 640 respondents were selected to participate in the study.

We used a multistage technique to select respondents from the community using the stages outlined below.

Stage 1:

Of the list of the political wards in Akure South and North local government areas (LGAs) which served as the sampling frame, through random sampling we selected sampling units from two LGAs, out of which four wards were selected from each.

Stage 2:

We enumerated all the streets in each of the selected wards.

Through simple random sampling, a settlement was selected from each ward.

Stage 3:

We randomly chose a central location in each of the selected streets by whirling a bottle. From the direction corresponding to the bottle top, data collection commenced and continued onward. All persons who met the inclusion criterion and provided consent from each of the streets were eligible to participate in the study. We conducted the interview until we obtained a quarter of the sample size from each community.

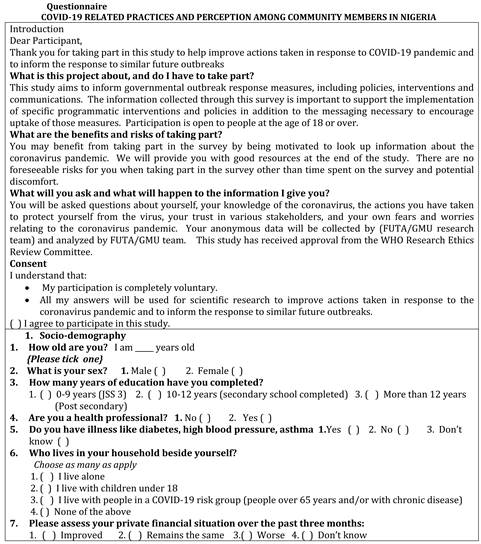

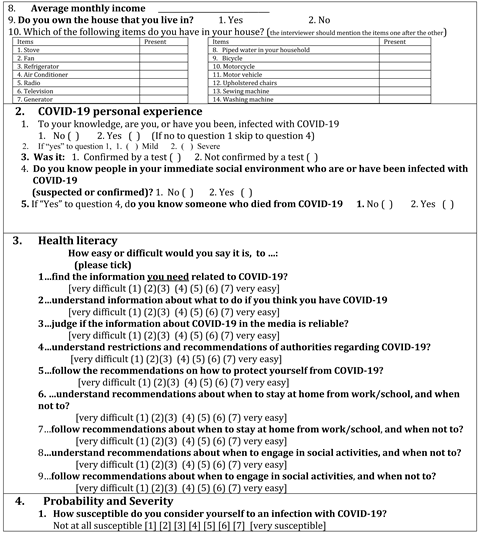

Data collection methods and instruments

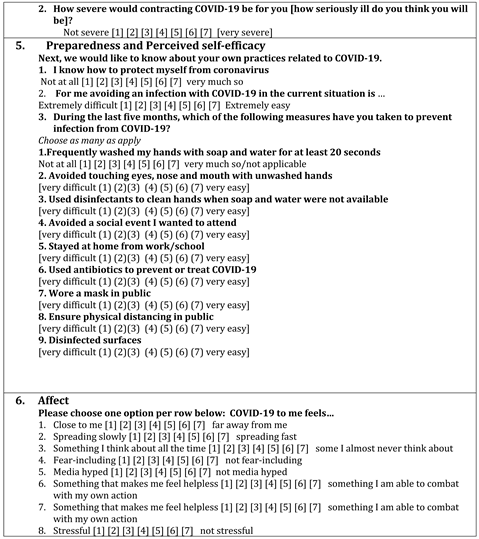

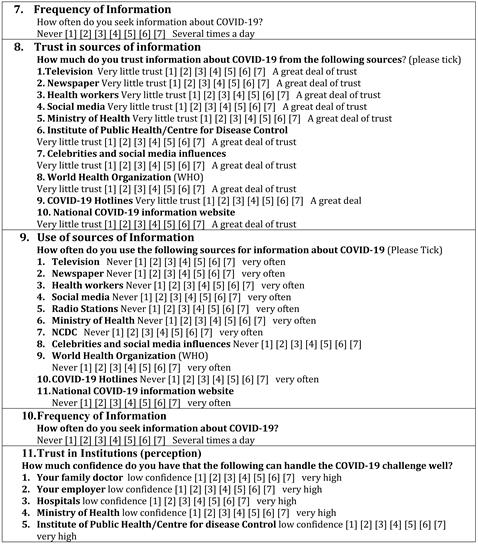

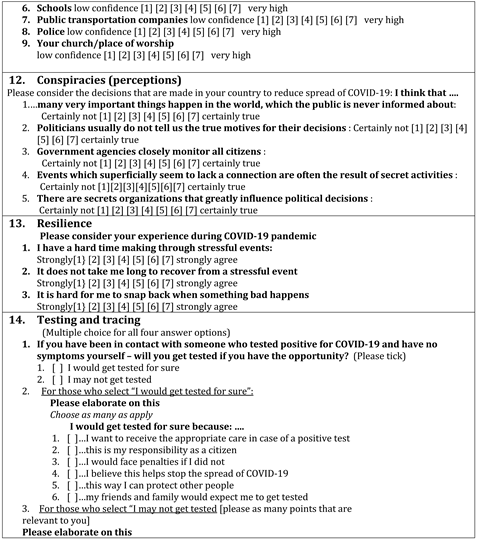

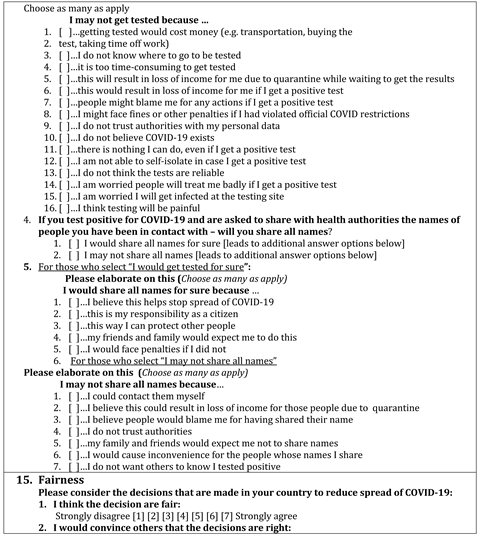

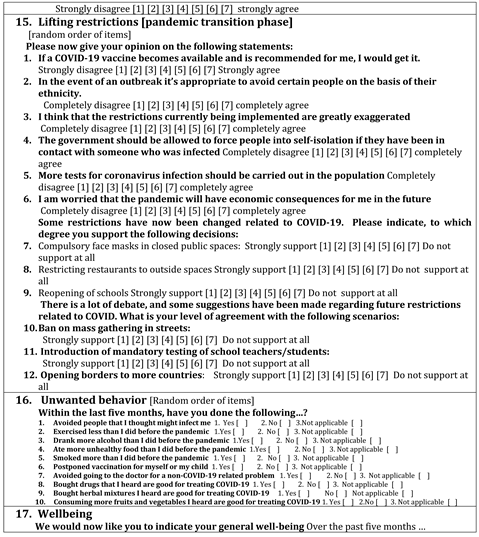

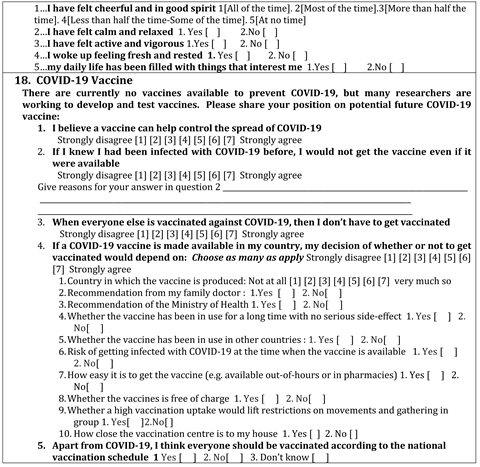

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was divided into 4 sections:

Section A: Socio-demographic characteristics. In this section, data were obtained on the age, sex, community of residence, highest level of education, occupation, living with children below 18 years, living with people in a COVID-19 at- risk group, financial situation over the past three months, average monthly income, and wealth quintile.

Section B: Perception regarding the suspension of COVID-19 restrictions in Nigeria.

Section C: Coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Section D: Level of trust regarding the sources of COVID-19 information.

Open-ended questions were asked regarding the coping strategies of community members during the COVID-19 pandemic. On a scale of “1-7”, we graded the level of trust of community members regarding the sources of COVID-19 information. We marked appropriately responses provided by the respondents. An infectious disease epidemiologist who presently volunteers as a member of the COVID-19 outbreak response team validated the questionnaire. We pre-tested the questionnaire among community members in a community that had not been enlisted in the study. Afterwards, ambiguous questions were simplified for ease of understanding. Back- translation of the questionnaire into Yoruba language was done by persons who had an excellent grasp of both Yoruba and English languages. The majority of the respondents had acquired minimal formal education; hence, the questionnaire was mainly administered in English language.

The independent variables in this study were the sociodemographic data as described above.

Outcome/dependent variables included the perception regarding the suspension of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions in Nigeria, coping practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, level of trust regarding the sources of COVID-19 information, and the determinants of COVID-19 health literacy among community members.

Trained research assistants (RAs) who had completed at least secondary school education were involved in the data collection process. The training lasted for two days: 29th and 30th September, 2020. The training exercise was conducted in Yoruba and English language to ensure accurate understanding of the data collection procedure. To ensure mastery of the activity, a practical session was held for the RAs shortly after the completion of the training exercise. Data were collected between 1st October and 9th October, 2020 by the RAs who were overseen by the field supervisor, the most educated of the RAs.

Data management

Data obtained from community members were input and analyzed in SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., USA) [12]. Age summary was done using mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages.

The socio-economic status indices were computed using the Principal Components Analysis (PCA) in SPSS. Data were obtained on the possession of the following household items: stove, radio, television, air conditioner, electric fan, refrigerator, pipe-borne water, bicycle, motor vehicle, upholstered chairs, sewing machine, and washing machine. Results obtained in this regard were input into SPSS. For the calculation of distribution cut points, quintiles were used. These were arranged in five categories: Q1=first, Q2=second, Q3=third, Q4=fourth, Q5=fifth, with “Q1” denoting the “lowest wealth index”, and “Q5” “the highest wealth index”.

A single question was asked to obtain information on the level of trust of community members on the following sources of information: television, newspaper, health workers, Ministry of Health, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, social media, COVID-19 hotlines, and the World Health Organization (WHO). The level of trust in each of the information sources was graded from “1” to “7” with “1” denoting “very little trust” and “7” “a great deal of trust”. To report the proportion of community members who had a great deal of trust on these information sources, we merged and reported the proportion of participants who had chosen options “6” and “7” in each instance. We conducted Chi-square tests to assess associations between sociodemographic characteristics and health literacy. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed on variables that were significant at the bivariate level. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Ethical considerations

To conduct this study, we obtained ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Federal Medical Centre, Owo, Ondo State (FMC/OW/380/Vol. XCVI/75). All study participants were informed of the right to withdraw from the study at any time prior to its completion without suffering any adverse consequence. Participants were asked to append their signatures on the consent form, but in cases where this was unlikely to be obtained, verbal consent was individually obtained from respondents. Assurance of the use of information obtained for research purposes only was made known to study participants. Anonymity of information was also ascertained, and information was kept safe on a password- protected computer. No form of harm was inflicted on study participants because of their participation.

Results

The mean age of the 691 respondents was 29.93±10.66 years, 352 (50.9%) were males, 183 (26.5%) were from Fanibi-FUTA community, and 341 (49.3%) lived with children below 18 years. Among them, the financial situation had improved over the past three months among 116 (16.8%), while 205 (66.3%) earned less than 30,000 naira monthly, and 138 (20.0%) belonged to the first wealth quintile (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of community members in Ondo State, Nigeria.

Regarding the suspension of COVID-19 restrictions in Nigeria, 291 (50.3%) respondents strongly supported that the restrictions were being exaggerated, and 351 (60.3%) strongly supported that the contacts of COVID-19 cases should be forced into self-isolation by the government. In addition, 334 (58.0%) respondents strongly supported the compulsory use of face masks in crowded public places, while 245 (42.9%) strongly supported the implementation of future ban on mass gathering in streets to prevent COVID-19 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perception of community members in Ondo State regarding the suspension of COVID-19 restrictions in Nigeria.

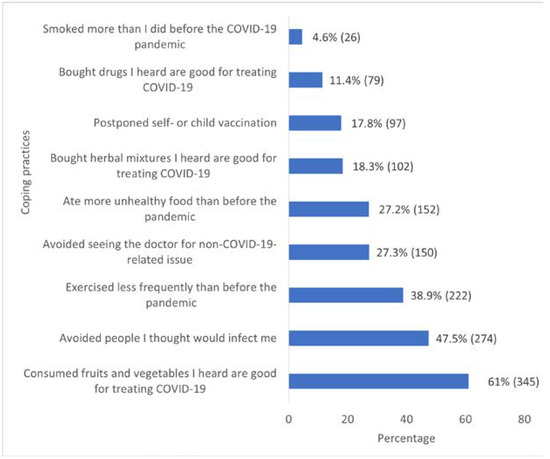

Pertaining to the coping practices among community members in Ondo State during the COVID-19 pandemic, 345 (61.0%) consumed fruits and vegetables they heard were good for treating COVID-19, 274 (47.5%) avoided people they thought would get them infected, and 222 (38.9%) exercised less frequently than they did before the pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Coping practices among community members in Ondo State during the COVID-19 pandemic.

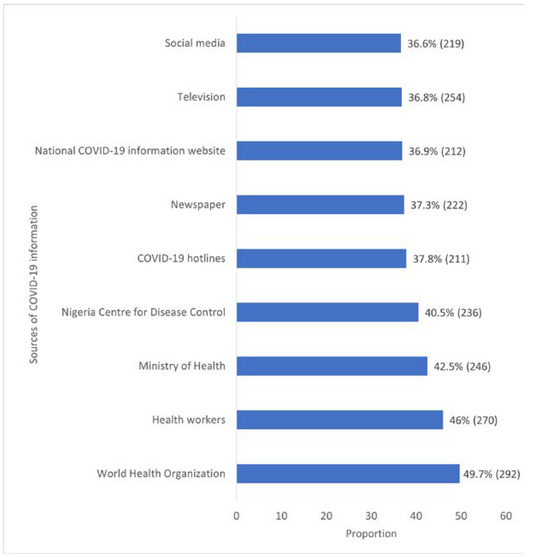

Among the respondents, 292 (49.7%) persons had high levels of trust in the WHO regarding COVID-19 information, while 246 (42.5%) trusted the Ministry of Health regarding COVID-19 information. The social media had the lowest level of trust regarding COVID-19 information among 219 (36.6%) respondents (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Level of trust of community members in Ondo State regarding the sources of COVID-19 information.

Among the respondents, 48 (43.6%) persons below 20 years had good health literacy, and 71 (39.8%) respondents between 21 and 29 years had good health literacy (χ2=13.595, p=0.004). Among males, 125 (45.6%) had good health literacy (χ2=0.008, p=0.929). Among the respondents, 31 (33.3%) in the first wealth quintile had good health literacy compared to 57 (53.3%) in the fifth wealth quintile (χ2=10.459, p=0.033) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between sociodemographic characteristics and COVID-19 health literacy among community members in Ondo State.

Respondents who were below 20 years were twice more likely to have good COVID-19 health literacy compared to those aged 40 years and above (AOR=2.304, 95%CI=1.316-4.034, p=0.004). Also, respondents aged 21-29 years were three times more likely to have good COVID-19 health literacy compared to those aged 40 years and above (AOR=2.587, 95%CI=1.559-4.293, p≤0.001). Respondents who belonged to the first wealth quintile were twice more likely to have good COVID-19 health literacy compared to their counterparts in the fifth wealth quintile (AOR=2.496, 95%CI=1.387- 4.493, p=0.002) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Determinants of COVID-19 health literacy among community members in Ondo State.

Discussion

This study found that different perceptions shaped the minds of community members regarding the suspension of COVID-19 restrictions in Nigeria, with an average proportion of individuals strongly supporting that the COVID-19 restrictions were being exaggerated. Such negative perceptions have lingered from the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria [2,8,13]. During this period, different reservations such as COVID-19 being described as a disease of the rich and mighty, an avenue for economic theft, and in some instances a non-existent illness have been widely accepted across many Nigerian communities [8,13]. Thus, it is expected that individuals who have strongly upheld the fallacies surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic would strongly support that the restrictions are unnecessary and exaggerated. Available evidence across the different channels of information dissemination presents that the COVID-19-related information were increasingly communicated at the early and mid-phases of the outbreak; however, fatigue has set in at the present phase [13,14]. Going onward, it is required that evidence-based COVID-19 information are intensified at all periods of the COVID-19 outbreak in community settings.

Findings from this study identified a strong support for COVID-19 tests among the members of Nigerian communities. This finding could have stemmed from the fear of many deaths that have been linked to the COVID-19 pandemic [15,16,17] Although reports present that many COVID-19-infected asymptomatic persons could infect others, the knowledge of one’s COVID-19 status assures of one’s health and keeps onward transmission of COVID-19 at bay [18,19].

From this study also, compulsory use of face masks in public places was strongly supported by community members. This elucidates that the adoption of preventive practices e.g., use of face masks has indeed been influenced by perception of the severity of COVID-19 among many individuals, validating the Health Belief Model [20].

Therefore, it is required that accurate reporting of COVID-19 is ensured to get community members informed on the severity of COVID-19, and thus practice the recommended safety guidelines. In addition, COVID-19 testing services should be made freely available to members of the population and decentralized to reduce the costs incurred by community members who enroll for tests.

We found that the re-opening of schools amid the COVID-19 outbreak in Nigeria was strongly supported. It is known that the COVID-19 lockdown impeded physical learning, and widened the inequality gap between the poor and rich in Nigeria due to the unaffordability of online schooling by the poor [20]. In addition, the implemented school lockdown measures largely delayed Nigeria’s realization of the Sustainable Development Goal 4: “Inclusive and Quality Education” [20]. However, reports from Massachusetts and the United States reveal a spike in the COVID-19 cases among children following school resumption [21]. Do we then forego children’s health in a bid to promote academic activities and income generation for schools? Certainly not! Therefore, it is highly pertinent that social distancing (at least 1 m), hand hygiene, temperature checks, and use of face masks are widely communicated and encouraged in school settings. On the other hand, opening of international borders gained disapproval among community members. This perception highlights that travelling in commercial automobiles is known as a risk factor for COVID-19. Although extending border closure could hinder international trade and economic growth, it is quintessential that provisions are made to ensure that the COVID-19 restrictions are not flouted during international travels.

We identified that community members in Ondo state adopted many coping practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. These included smoking, reduced exercise, and the consumption of fruits and vegetables. At different periods of the outbreak, invalid evidence on the effectiveness of fruits and vegetables in preventing COVID-19 was widely accepted, and thus resulted in compulsive consumption of such. Similarly, rumors on the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine and other drugs resulted in an increased demand for such, with an increased cost of purchasing hydroxychloroquine [22]. Resilience, mental disengagement, information seeking and consultation, and spiritual and social support have been identified as coping strategies [23]. Elevated mental stress has however been reported as a coping strategy among Chinese adults, while stress-reduction activities such as exercise have been reported among health workers in New York during the COVID-19 outbreak. However, it is essential that during outbreaks, coping strategies which have positive effects on individual and family health are outlined and communicated to members of the population to ensure overall health in the population.

In this study, we found that high levels of trust were placed on the WHO, health workers, Ministry of Health, and the NCDC. This finding posits that the aforementioned custodians of health could provide more credible information on the COVID-19 outbreak compared to the social and traditional media where rumors are regularly promoted. Other studies conducted in Nigeria have reported the following sources of COVID-19 information: radio, television, newspaper, jingles, and social media; however, information from these channels cannot be trusted in all instances. Rather, COVID-19 information obtained from either health agencies or workers should gain more credence among community members. In lieu of this, the Nigerian communication should be kept abreast of the COVID-19 situation through the health agencies resident in Nigeria.

We found that health literacy could be determined by age group and wealth quintiles. In this study, persons below 20 years were twice more likely to have good health literacy compared to those aged 40 and above. Also, persons in the 21-29 age group were twice more likely to have good health literacy compared to those aged 40 and above. This finding therefore posits that younger individuals are more likely to understand and utilize health decisions, thus taking responsibility for both self and family health. However, this finding contradicts anecdotal evidence that increasing age is an indicator for utilizing health decisions and being responsible for self and family health. Culling lessons from the Bowen Family Systems theory, good health decisions could enhance family coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic [24]. In maintaining family harmony, family health, and happiness, research conducted in China reported that health literacy is key [25]. “Distributed health literacy” could also be achieved when one or more member(s) of the family has (have) good health literacy. Considering the patriarchal nature of many Nigerian families, family health decisions cannot be committed into the hands of younger individuals. It is therefore required that younger persons are empowered in the families to make contributions to health decisions, and thus improve family health.

We found that persons in the first wealth quintile are twice more likely to have good health literacy compared to those in the fifth wealth quintile. Since persons in this category are poor, they are both more exposed to and utilize health information because they cannot afford treatment costs. It can thus be posited that the lower a person’s socioeconomic status is, the more likely he is to have good health literacy. The findings in this study are however contrary to the predictions that higher socioeconomic status is a determinant of good health literacy [25]. In the COVID-19 context, non-pharmaceutical measures have been recommended at minimal cost for the containment of COVID-19, and this therefore makes the acceptance and practicality of these measures more possible among poorer individuals. In lieu of this, adequate health information should be increasingly provided across many media platforms especially the modern platforms to improve health literacy among rich individuals.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 outbreak has been characterized by different perceptions among members of Nigerian communities. Notable levels of stress have been experienced for which different coping mechanisms, positive and negative, have been adopted. Information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic has been communicated across different information sources, and high levels of trust are placed on the WHO, health workers, Ministry of Health, and the NCDC by community members. The use of face masks in public places and COVID-19 testing have gained wide acceptance among community members, however total compliance is yet to be achieved. Thus, active engagement of youths and young adults is required in COVID-19 risk communication messages to influence good health literacy among members of the community.

Author Contributions

VOU, TAF, and OSI conceptualized the study. VOU and OSI supervised data collection. OSI performed data analysis. VOU and OSI wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All three authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors—none to declare.

Appendix A

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is health literacy? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Ilesanmi, O.; Afolabi, A. Perception, and practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in an urban community in Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. PeerJ. 2020, 8, e10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluh, D.O.; Onu, J.U. The need for psychosocial support amid COVID-19 crises in Nigeria. Psychol Trauma. 2020, 12, 557–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olapegba, P.O.; Ayandele, O.; Kolawole, S.O.; Oguntayo, R. COVID-19 knowledge and perceptions in Nigeria. PsyArXiv preprint. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Miron, V.D. COVID-19 in the pediatric population and parental perceptions. Germs. 2020, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldometer. COVID-19: Coronavirus pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Nigeria Center for Disease Control. COVID-19 Nigeria stories. 2020. Available online: https://covid19blog.ncdc.gov.ng/ (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Iorfa, S.K.; Ottu, I.F.A.; Oguntayo, R.; et al. COVID-19 knowledge, risk perception and precautionary behavior among Nigerians: A moderated mediation approach. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 566773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; et al. Coping style, social support and psychological distress in the general Chinese population in the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2020, 20, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britannica. Ondo State, Nigeria. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Ondo-state-Nigeria (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Nigeria Center for Disease Control. COVID-19 Nigeria. 2020. Available online: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/ (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY.

- Ilesanmi, O.S.; Bello, A.E.; Afolabi, A.A. Fatigue in the COVID-19 pandemic response in Africa: Causes, consequences, and counter-measures. Pan Afr Med, J. 2020, 37 Suppl 1, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilesanmi, O.S.; Afolabi, A.A. Six months of COVID-19 response, in Nigeria: Lessons, challenges, and way forward. J Ideas Health. 2020, 3, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. Deaths in Nigerian city raise concerns over undetected COVID-19 outbreaks. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/28/nig erian-authorities-deny-wave-of-deaths-is-due-to-covid-19 (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- MSN News. Fear of COVID-19 as 57 die mysteriously in Enugu. 2020. Available online: https://www.msn.com/en- xl/news/other/fear-of-covid-19-as-57-die-mysteriously-in- enugu/ar-BB1aKbc7 (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Rentsch, C.T.; Kidwai-Khan, F.; Tate, J.P.; et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan Başer, D.; Çevik, M.; Gümüştakim, Ş.; Başara, E. Assessment of individuals’ attitude, knowledge, and anxiety towards COVID-19 at the first period of the outbreak in Turkey: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2020, 74, e13622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkang, E.E.; Zotor, F.B. Application of the health belief model (HBM) in HIV prevention: A literature review. Cent Afr J Public Health. 2015, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ilesanmi, O.S.; Afolabi, A.A.; Adebayo, A.M. Problematic internet use (PIU) among adolescents during COVID-19 lockdown: A study of high school students in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Inf Commun. 2021, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: State-level data report. 2020. Available online: https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel- coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19- state-level-data-report (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Punch. Nigerians purchasing hydroxychloroquine in large quantities, says PTF. 2020. Available online: https://punchng.com/nigerians- purchasing-hydroxychloroquine-in-large-quantities-says- ptf (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Ilesanmi, O.S.; Afolabi, A.A. In search of the true prevalence of COVID-19 in Africa: Time to involve more stakeholders. Int J Health Life Sci. In press. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Bowen family systems theory and practice: Illustration and critique. Aust N Z J Fam Ther. 1999, 20, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y.H.; Wai, A.K.C.; Zhao, S.; et al. Association of individual health literacy with preventive behaviors and family well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: Mediating role of family information sharing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2021.