Case report

A 27-year-old male, previously healthy, presented with a 7-day history of sore throat and fever. He was diagnosed initially with acute bacterial pharyngotonsillitis and was treated on an outpatient basis with oral azithromycin 500 mg OD. On the 2nd day, he began to experience cough and dyspnea and was transferred to our hospital. At admission, the patient was in poor general condition with tachycardia, fever, tachypnea and hypotension. Hyperemia was observed in the oropharynx with multiple necrotic tonsillar lesions as well as necrotic lesions in the back and bilateral buttocks. The initial investigation showed thrombocytopenia (6.000/mm3), leukocytosis (12,710 cells/mm3) with a left shift, increased creatinine (2.51 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (75 mg/dL), elevated total serum bilirubin (17.2 mg/dL) and direct bilirubin (11.7 mg/dL) and hyperlactatemia (3.37 mmol/L). Bilateral lung opacities on chest radiograph were documented, a transthoracic echocardiography was performed, and it ruled out any vegetation or any findings suggestive of endocarditis. Initially, the diagnosis of LS was not considered and antibiotic therapy for severe community acquired pneumonia was started with intravenous cefepime 2 g every 8 h, intravenous linezolid 600 mg every 12 h and intravenous clarithromycin 500 mg every 12 h. During the first day of hospitalization the patient exhibited progressive dyspnea with acute respiratory failure requiring orotracheal intubation and management in the intensive care unit.

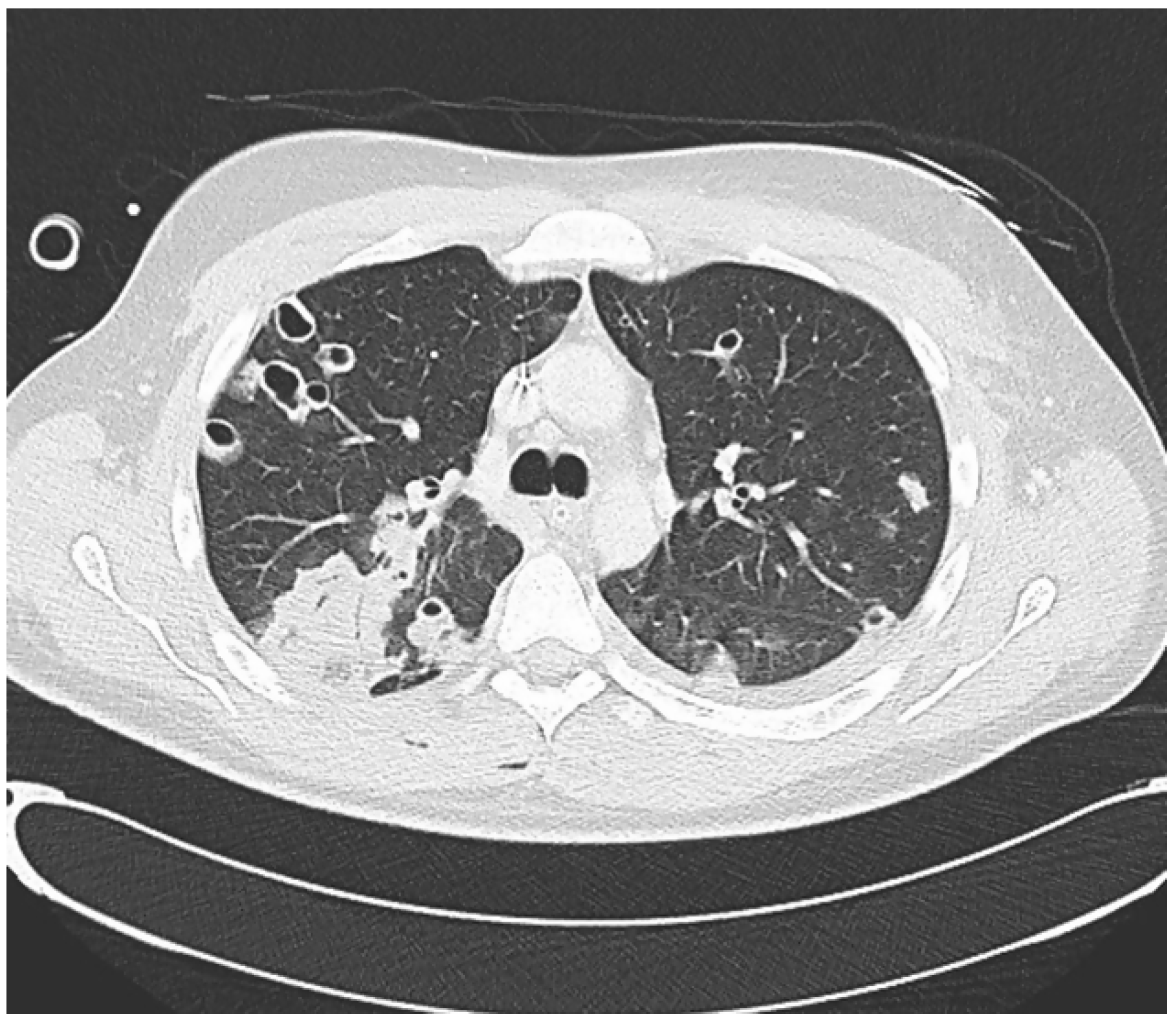

A CT scan of the thorax showed multiple pulmonary nodules some of which showed central cavitation distributed through the lung parenchyma corresponding to septic emboli with areas of ground-glass pattern (

Figure 1).

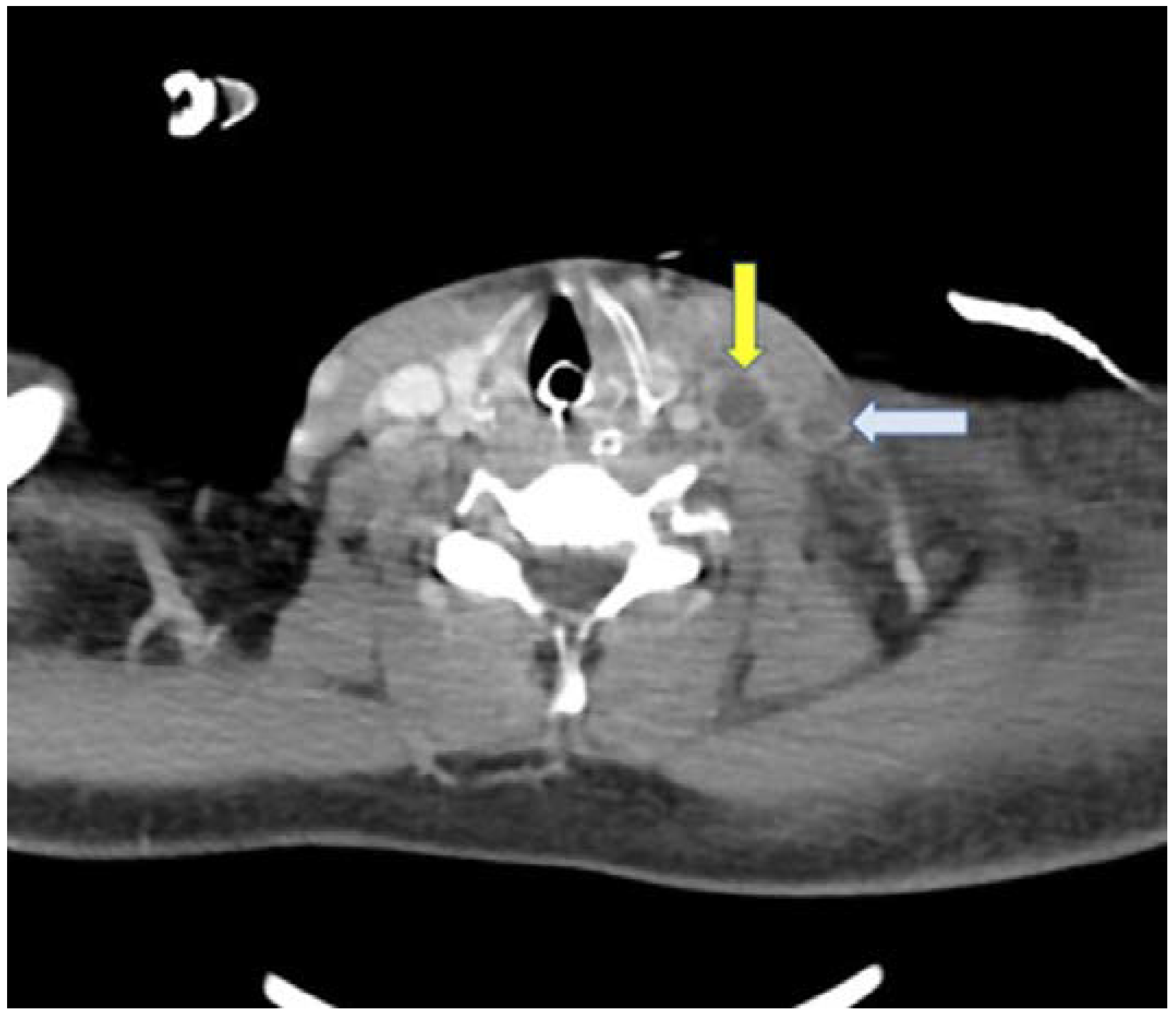

A new physical examination revealed a left cervical bulging (

Figure 2) and a contrast-enhanced neck CT scan was carried out, which revealed a thrombus in the left internal and external jugular vein (

Figure 3).

On day 1, B. circulans, F. nucleatum and S. aureus were detected in blood cultures and according to the antibiotic susceptibility testing the patient was treated with meropenem and linezolid due to the acute kidney injury. After the antibiotic adjustment, the patient`s evolution was favorable. The patient was discharged after 4 weeks of antibiotic treatment with intravenous meropenem 2 g every 8 hours and subcutaneous enoxaparin 80 mg twice a day for 6 months.

The initial finding of pharyngeal infection accompanied by sepsis in combination with confirmation of jugular vein thrombosis, pulmonary septic emboli, and the presence of B. circulans and F. nucleatum confirmed the diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome. The patient completed the entire antibiotic regimen and anticoagulation was suspended 6 months after hospitalization. He is being followed by otorhinolaryngology, internal medicine, and vascular surgery physicians.

Discussion

This case presents some unusual findings. Firstly, even though LS is caused mainly by F. necrophorum, this patient had a coinfection by F. necrophorum, B. circulans and S. aureus, without the evidence of right-sided infective endocarditis. Moreover, there is limited data about LS with the isolation of S. aureus, even more in a patient without any risk factors for this pathogen and more interestingly, with the coinfection with F. necrophorum and B. circulans. Finally, while LS classically compromises the internal jugular vein (IJV), this patient had compromised IJV and external jugular vein (EJV).

Many authors have stated that LS incidence is rising. Data from Sweden showed that in a follow up period of 8 years, the incidence of LS increased from 1.0 to 1.7 cases per million per year [

4]. Similarly, data from Denmark showed an increase in the incidence from 0.8 cases per million per year up to 3.6 cases per million per year, from 1998 to 2001, respectively. Nonetheless, it is hypothesized that the real incidence is much higher [

5]. Many theories have emerged about this increase, but unfortunately no theory has clarified the reason of this increase.

This disease is usually caused by anaerobic bacteria of the normal oropharyngeal flora, it is mainly caused by

F. necrophorum, Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria of the oropharyngeal flora with some unique virulence factors such as the production of leukotoxins that could be the reason of the characteristic necrotic abscesses, the presence of lipopolysaccharide that induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines and the production of hemagglutinin that could be involved in thrombus formation [

1]. Concerning the infection by

B. circulans, these are Gram positive or Gram variable spore-forming rods usually distributed in the natural environment, but some can cause severe infections as opportunistic pathogen [

6].

B. circulans has been isolated from cases of meningitis, endocarditis, wound infection and endophthalmitis yet most cases were in immunocompromised patients. Most positive cultures are considered laboratory contaminants, which may cause to be ignored in treatment strategies [

6]. Unfortunately, we do not know how the patient acquired these bacteria. To our knowledge this is the first case of LS by

B. circulans and

F. nucleatum.We have conducted a research in Pubmed, with the terms “Lemierre’s syndrome” and “

S. aureus” and between 2002 to this date, only 27 cases have been reported, with some cases in pediatric population, some cases in patients with a known risk factor for this pathogen or patients with a predisposing infection (pneumonia or skin infections). Given the scarce data on the role of this pathogen in this syndrome, little can be concluded, but it is a new scenario to considered, since it has become an important cause of LS in the last decades [

7].

Concerning the spread of the infection from the tonsils to the internal jugular veins, several theories exist. It could be secondary to hematogenous spread via the tonsillar vein that drains in the IJV. Another theory implies that lymphangitis and lymphadenitis were the primary processes with secondary extension to the veins causing a periphlebitis and endophlebitis with associated thrombosis and finally, another possible mechanism involves the spreading of the pus collections deeper into the loose connective tissue of the pharynx and their attachment to the walls of the veins [

1]. Regarding the compromise of the EJV, like the one in our case, the carotid sheath that encloses the EJV is located close to the parapharyngeal space and the EJV is located over these tissues. Due to this, direct invasion of pharyngeal infection to EJV without involvement of surrounding tissues or anomalous vascular connection scarcely occurs [

8]. Due to this, involvement of the IJV and the EJV like our case is unusual with only a few cases reported as far as we are aware.

Clinical presentation is characterized by nonspecific symptoms like sore throat, fever and cervical pain. During physical examination the tonsils can appear exudative, hyperemic, ulcerated, or with normal appearance; nonetheless, these findings can disappear without antibiotic treatment. Septic embolism or septic thrombophlebitis occurs usually 1 to 3 weeks after the initial presentation [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Symptoms of internal jugular thrombosis include pains, swelling, fever and trismus [

2]. It is important to mention that once septic thrombophlebitis has occurred, embolism to other organs such as the lungs can mask the clinical presentation and confuse the clinician especially with septic embolism to the lungs which can be present in up to 97% of patients with LS [

2].

Diagnosis requires recent oropharynx infection; clinical or radiological evidence of IJV thrombosis; isolation of anaerobic pathogens and at least one septic focus. In those cases in which a pathogen cannot be identified and having in mind the fact that cultures for anaerobic pathogens can take 5–8 days to grow delaying antimicrobial treatment, the presence of the previous criteria without isolation of anaerobic pathogens should rise suspicion of LS [

2,

10]. Anaerobic blood cultures are fundamental for the diagnostic approach in these patients [

1]. However, novel techniques by molecular detection have emerged in the last decades that would facilitate a rapid diagnostic of

F. necrophorum.

Treatment consists of antibiotic therapy with coverage for anaerobes, staphylococci and streptococci with antibiotics adjustment according to the antibiotic susceptibility testing results [

11].

Fusobacterium is intrinsically resistant to gentamicin and quinolones and tetracyclines have relatively poor activity [

1]. Macrolides resistance is common and could be the reason why our patient had clinical worsening despite being treated initially with azithromycin [

1]. The suggested length of the therapy is 3 to 6 weeks [

2].

The role of anticoagulation therapy in LS is not well understood. Recent data, suggest that patients with LS have a substantial risk of new thromboembolic complications. Nonetheless, many of the patients with LS are not on anticoagulation therapy due to the suspected high risk of bleeding [

12]. An observational study from Sweden found that most of the patients with LS recovered well without anticoagulation therapy [

13]. Ultimately, the role of anticoagulation in this disease should be answered with a randomized controlled trial.