Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-II: Bio-Sorbent Materials for Removal of Dyes, Heavy Metals and Toxic Chemicals from Polluted Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Citrus Waste Pre-Treatment and Disposal

- (a)

- Dilute wastewaters: This includes, (i) fruit-rinsing water, (ii) surface condenser water and (iii) water from barometric condensers of evaporators. This disposal contains good quantities of carbohydrates and a low concentration of nitrogen, unlike domestic sewage which has the opposite composition, i.e., low in carbohydrates and rich in nitrogen. This can be released to water bodies without any fear of adverse effects to the ecosystem.

- (b)

- Wastewater of intermediate concentration: This includes, (i) floor washing, (ii) equipment clean-up water and (iii) sectionizing wastewater. This contains solid waste concentrations ranging from trace amounts to ~2%. This requires some level of treatment prior to disposal to water bodies.

- (c)

- Concentrated wastewaters: This includes, (i) dripping waters from can closing and filling machines, (ii) effluent from peel-oil centrifugal and (iii) waste alkali from sectionizing or evaporator cleaning. This contains 2–6% of soluble solids and high concentrations of organic materials.

1.2. Pollutants: Dyes, Heavy Metals, Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PACs) and Other Contaminants

1.3. Health Hazards of Pollutants

1.4. Citrus Peel-Derived Adsorbent Materials

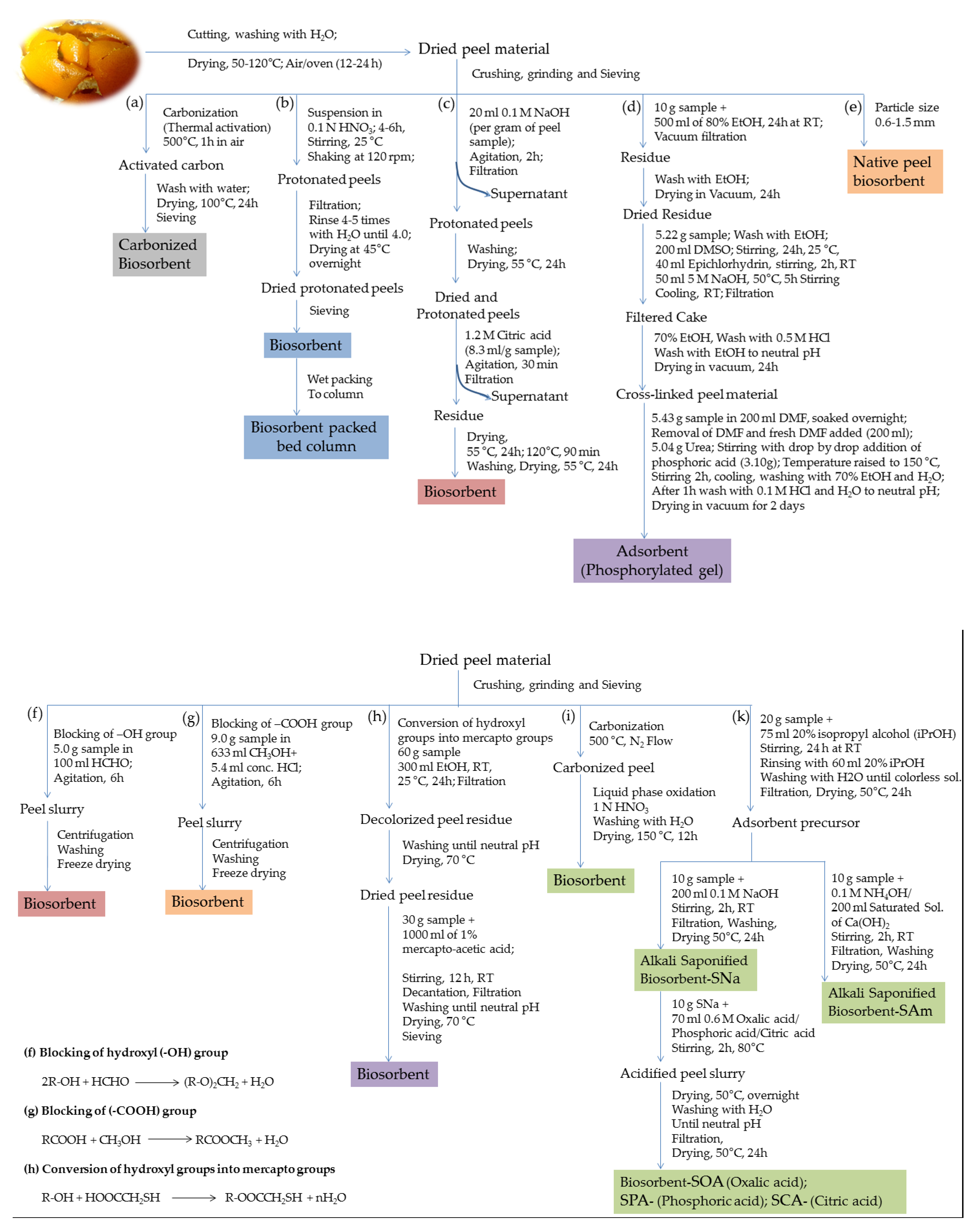

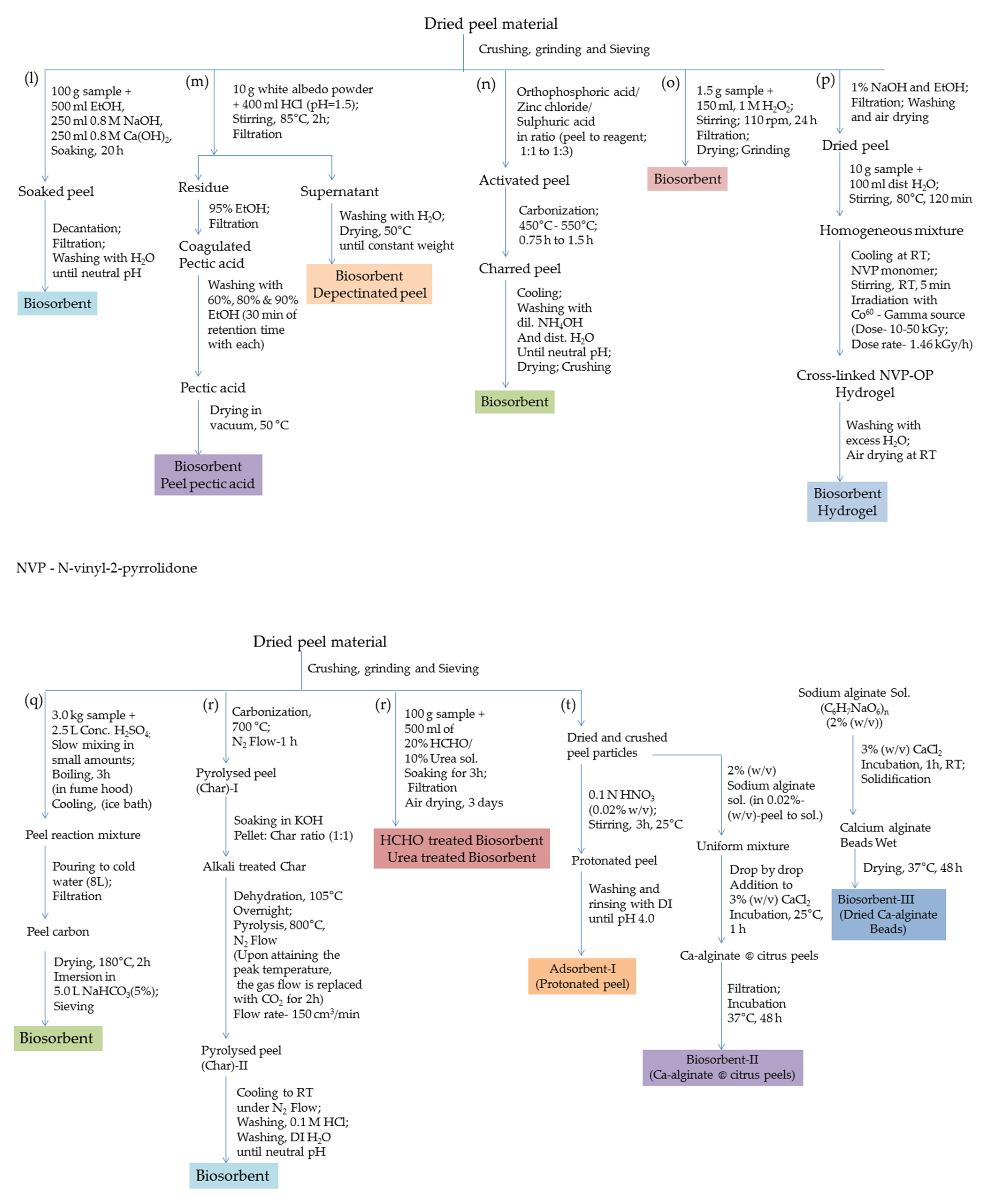

2. Methods of Preparation of Bio-Sorbents

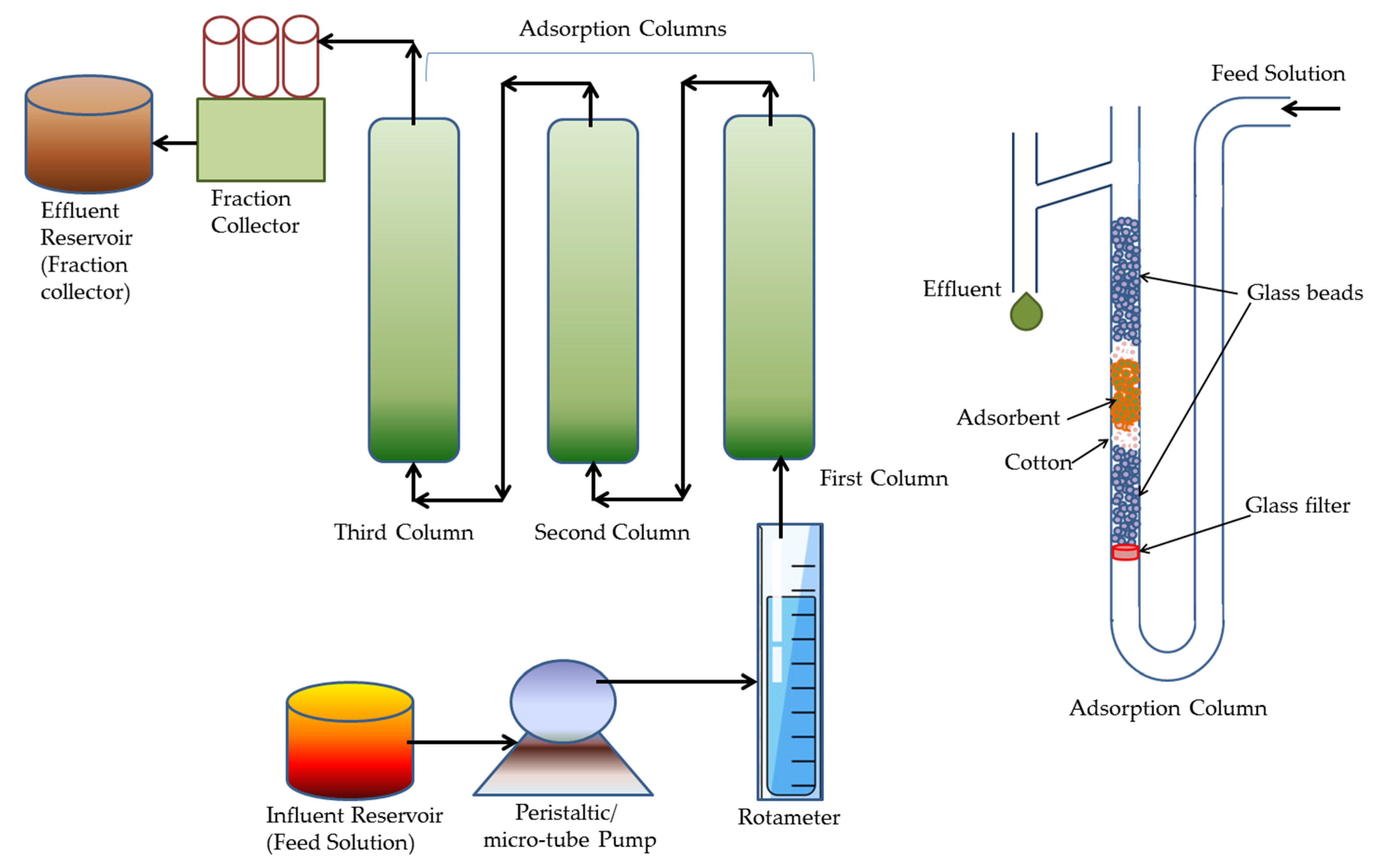

3. Adsorption Experiments and Mechanism

4. Kinetics and Thermodynamics

4.1. Kinetics

4.2. Thermodynamic Observations

5. Design of Experiments

6. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Sinha, M.; Baral, E.R.; Koteswararao, R.; Dhyani, A.; Cho, M.H.; Cho, S. Bio-sorbents, industrially important chemicals and novel materials from citrus processing waste as a sustainable and renewable bioresource: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 23, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, N.; Sinha, M.; Sharma, K.; Koteswararao, R.; Cho, M.H. Cho Modern Extraction and Purification Techniques for Obtaining High Purity Food-Grade Bioactive Compounds and Value-Added Co-Products from Citrus Wastes. Foods 2019, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Sinha, M.; Cho, M.H. Citrus waste derived nutra-/pharmaceuticals for health benefits: Current trends and future perspectives. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Nabybaccus, F.; Cho, M.H. Pharma-/Nutraceutical Applications. Eras J. Med. Res. 2016, 3, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Rao, R.K.; Sinha, M.; Baral, E.R.; Cho, M.H. Citrus essential oils: Extraction, authentication and application in food preservation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 59, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, Y.R. Converting citrus wastes into value-added products: Economic and environ-mently friendly approaches. Nutrition 2017, 34, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Lee, Y.R. Extraction, characterization and biological activity of citrus flavonoids. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 35, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sharma, K.; Sinha, M.; Dhyani, A.; Pathak, B.; Jang, H.; Park, S.; Pashikanti, S.; Cho, S. Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-I: Production of Biofuel and Valuable Compounds by Fermentation. Processes 2021, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, M.; Nolan, K.; Collins, C.; Carty, G.; Donlon, B.; Brøgger, M. European Environment Agency Topic Report: Biodegradable Municipal Waste Management in Europe; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Chemistry and Technology of Citrus. In Citrus Products Agriculture Handbook; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1956; Volume 98, pp. 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal, B.F. Citrus Waste Research Project FLA; State Bd Health Bur. Sanit. Engin. Final Rpt; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1953; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Annonymous. Grappling with that problem of citrus waste odors. Food Eng. 1954, 26, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Sanborn, N. Spray irrigation as a means of cannery waste disposal. Cann. Trade 1952, 74, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ingols, R. The citrus canning disposal problem in Florida. Sew. Work. J. 1945, 17, 320–329. [Google Scholar]

- McNary, R.R. Citrus Canning Industry. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1947, 39, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanborn, N. Nitrate treatment of cannery wastes. Fruit Prod. J. Am. Vineg. Ind. 1941, 20, 207–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, C.H. Citrus Fruits. Nature 1915, 96, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J. The results of research on citrus waste disposal. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 1953, 246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock, D.I.; Allen, W.E. Germicidal Effect of Orange Peel Oil and D-Limonene in Water and Orange Juice. Food Technol. 1960, 14, 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Subba, M.S.; Soumithri, T.C.; Rao, R.S. Antimicrobial Action of Citrus Oils. J. Food Sci. 1967, 32, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. Industrial wastes as low-cost potential adsorbents for the treatment of wastewater laden with heavy metals. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 166, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshabanat, M.; Alsenani, G.; Almufarij, R. Removal of crystal violet dye from aqueous solutions onto date palm fiber by ad-sorption technique. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusick, D. Genotoxicity of Phenolic Antioxidants. Toxicol. Ind. Health 1993, 9, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dich, J.; Zahm, S.H.; Hanberg, A.; Adami, H.O. Pesticides and cancer. Cancer Causes Control 1997, 8, 420–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.; Ngo, H.; Guo, W.; Nguyen, T.V.; Vigneswaran, S. Performance of cabbage and cauliflower wastes for heavy metals removal. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, D.; Arthington, A.H.; Gessner, M.O.; Kawabata, Z.-I.; Knowler, D.J.; Lévêque, C.; Naiman, R.J.; Prieur-Richard, A.-H.; Soto, D.; Stiassny, M.L.J.; et al. Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintern, A.; Leahy, P.J.; Heijnis, H.; Zawadzki, A.; Gadd, P.; Jacobsen, G.; Deletic, A.; Mccarthy, D.T. Identifying heavy metal levels in historical flood water deposits using sediment cores. Water Res. 2016, 105, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Du, P.; Yu, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Lin, H.; Luo, Y.; Xie, H.; Guo, J.; et al. Increases of Total Mercury and Methylmercury Releases from Municipal Sewage into Environment in China and Implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1061–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, N.; Oladegaragoze, A.; Djafarzadeh, N. Decolorization of basic dye solutions by electrocoagulation: An investigation of the effect of operational parameters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 129, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, Y.; Paknikar, K. Development of a process for biodetoxification of metal cyanides from waste waters. Process. Biochem. 2000, 35, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, A.B. Recovery of Metal Cyanides Using a Fluidized Bed of Resin. Master’s Thesis, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa, December 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.A.Q.; Ntwampe, S.K.O.; Doughari, J.H.; Muchatibaya, G. Application of Citrus sinensis Solid Waste as a Pseudo-Catalyst for Free Cyanide Conversion under Alkaline Conditions. Bioresources 2013, 8, 3461–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostich, M.S.; Batt, A.L.; Lazorchak, J. Concentrations of prioritized pharmaceuticals in effluents from 50 large wastewater treatment plants in the US and implications for risk estimation. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessa, E.F.; Nunes, M.L.; Fajardo, A.R. Chitosan/waste coffee-grounds composite: An efficient and eco-friendly adsorbent for removal of pharmaceutical contaminants from water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 189, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J. Pollution from drug manufacturing: Review and perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Lu, G.; Liu, J.; Jin, S. An integrated assessment of estrogenic contamination and feminization risk in fish in Taihu Lake, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 84, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi, A. Chemically modified bio-sorbents and their role in the removal of emerging pharmaceutical waste in the water system. Water 2020, 12, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, G.; Naidoo, V.; Cuthbert, R.; Green, R.E.; Pain, D.J.; Swarup, D.; Prakash, V.; Taggart, M.; Bekker, L.; Das, D.; et al. Removing the Threat of Diclofenac to Critically Endangered Asian Vultures. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oaks, J.L.; Gilbert, M.; Virani, M.Z.; Watson, R.T.; Meteyer, C.U.; Rideout, B.A. Diclofenac residues as the cause of vulture population decline in Pakistan. Nature 2004, 427, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, S.; Baral, H.S.; Charman, S.; Cunningham, A.A.; Das, D.; Ghalsasi, G.R.; Goudar, M.S.; Green, R.E.; Jones, A.; Nighot, P.; et al. Diclofenac poisoning is widespread in declining vulture populations across the Indian subcontinent. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2004, 271, S458–S460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.E.; Newton, I.; Shultz, S.; Cunningham, A.A.; Pain, D.J.; Prakash, V. Diclofenac Poisoning as a Cause of Vulture Population Declines across the Indian Subcontinent. J. Appl. Ecol. 2004, 41, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Pain, D.; Cunningham, A.; Donald, P.; Verma, A.; Gargi, R.; Sivakumar, S.; Rahmani, A. Catastrophic collapse of Indian white-backed Gyps bengalensis and long-billed Gyps indicus vulture populations. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 109, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J. Industrial Wastewater Treatment Technology, 2nd ed.; Patterson, J., Ed.; Butterworth Publishers: Stoneham, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, B.; Tan, I.A.W.; Ahmad, A.L. Optimization of basic dye removal by oil palm fibre-based activated carbon using response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 158, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, H.; Garg, V.; Gupta, R. Removal of a basic dye from aqueous solution by adsorption using Parthenium hysterophorus: An agricultural waste. Dye Pigment. 2007, 74, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Gu, Y.; Yang, Z. Application of biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2015, 125, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. Removal of methylene blue dye from artificially contaminated water using Citrus limetta peel waste as a very low cost adsorbent. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 66, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking—Water Quality; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Purkayastha, D.; Mishra, U.; Biswas, S. A comprehensive review on Cd(II) removal from aqueous solution. J. Water Process. Eng. 2014, 2, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Sinha, S.; Singh, D.K. Chromium(VI) removal from aqueous solution and industrial wastewater by modified date palm trunk. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2014, 34, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Shah, J.A.; Ashfaq, T.; Mubashar, S.; Gardazi, H.; Tahir, A.A. Waste biomass adsorbents for copper removal from industrial wastewater-A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 263, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N. Lead Removal from Water by Low Cost Adsorbents: A Review. Pak. J. Anal. Environ. Chem. 2012, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawade, S.M.; Gaikwad, R.W. Removal of Zinc Ions from Industrial Effluent by Using Cork Powder as Adsorbent. Int. J. Chem. Eng. Appl. 2011, 2, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.P.; Majumder, C.B. Flouride removal from sewage water using Citrus limetta peel as bio-sorbent. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 8, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, A.; Nayak, A.K.; Singh, J. Synthesis of FeCl3-activated carbon derived from waste Citrus limetta peels for removal of fluoride: An eco-friendly approach for the treatment of groundwater and bio-waste collectively. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolas, H.; Sahin, O.; Saka, C.; Demir, H. A new method on producing high surface area activated carbon: The effect of salt on the surface area and the pore size distribution of activated carbon prepared from pistachio shell. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Bolgaz, T.; Saka, C.; Şahin, Ö. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from cotton stalks in a two-stage process. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2011, 92, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, C.; Sahin, O.; Celik, M.S. The Removal of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solutions by Using Microwave Heating and Pre-boiling Treated Onion Skins as a New Adsorbent. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2012, 34, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Y.; Aydın, H. A kinetics and thermodynamics study of methylene blue adsorption on wheat shells. Desalination 2006, 194, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivelan, V.; Kumar, K.V. Equilibrium, kinetics, mechanism, and process design for the sorption of methylene blue onto rice husk. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 286, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.T.; Islam, M.A.; Mahmud, S.; Rukanuzzaman, M. Adsorptive removal of methylene blue by tea waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annadurai, G.; Juang, R.-S.; Lee, D.-J. Use of cellulose-based wastes for adsorption of dyes from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2002, 92, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.G.; Sharma, A. Kinetics and thermodynamics of Methylene Blue adsorption on Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf powder. Dye Pigment. 2005, 65, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G.; Porter, J.F.; Prasad, G.R. The Removal of Dye Colours from Aqueous Solutions by Adsorption on Low-cost Materials. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1999, 114, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgher, M.; Bhatti, H.N. Removal of reactive blue 19 and reactive blue 49 textile dyes by citrus waste biomass from aqueous solution: Equilibrium and kinetic study. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 90, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, H.N.; Bajwa, I.I.; Hanif, M.A.; Bukhari, I.H. Removal of lead and cobalt using lignocellulosic fiber derived from Citrus reticulata waste biomass. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.W.; Kotte, P.; Wei, W.; Lim, A.; Yun, Y.S. Bio-sorbents for recovery of precious metals. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Schiewer, S.; Cameron, R. Mechanistic elucidation and evaluation of biosorption of metal ions by grapefruit peel using FTIR spectroscopy, kinetics and isotherms modeling, cations displacement and EDX analysis. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh Babu, C.; Chakrapani, C.; Somasekhara Rao, K. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of reactive red 2 dye adsorption onto prepared activated carbons. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2011, 3, 428–439. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Luo, J.; Hu, M.; Lai, K.; Geng, P.; Huang, H. Enhancement of cypermethrin degradation by a coculture of Bacillus cereus ZH-3 and Streptomyces aureus HP-S-01. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Ganguly, A.; Gupta, S.; Basu, S. Application of Response Surface Methodology for preparation of low-cost adsorbent from citrus fruit peel and for removal of Methylene Blue. Desalination 2011, 275, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, G.A.; Abdel-Aal, S.E.; Badway, N.A.; Elbayaa, A.A.; Ahmed, D.F. A novel hydrogel based on agricultural waste for removal of hazardous dyes from aqueous solution and reuse process in a secondary adsorption. Polym. Bull. 2016, 74, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Zafar, J.; Nisar, H. Adsorption Studies of Removal of Indigo Caramine Dye from Water by Formaldehyde and Urea Treated Cellulosic Waste of Citrus reticulata Peels. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Salman, M.; Mahmud, T.; Kanwal, F.; Waheed-Uz-Zama. Utilization of chemically modified Citrus reticulata peels for biosorptive removal of acid yellow-73 dye from water. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 2013, 35, 611–616. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, S.; Khamkhash, A.; Ghosh, T.; Aggarwal, S. Adsorptive Removal of Se(IV) by Citrus Peels: Effect of Adsorbent Entrapment in Calcium Alginate Beads. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 17215–17222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, S.K.; Lee, M.G. Adsorption characteristics of antibiotics amoxicillin in aqueous solution with activated carbon prepared from waste citrus peel. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2018, 29, 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, E.K.; Pranowo, R.; Sunarso, J.; Indraswati, N.; Ismadji, S. Performance of activated carbon and bentonite for adsorption of amoxicillin from wastewater: Mechanisms, isotherms and kinetics. Water Res. 2009, 43, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi, G.; Alahabadi, A.; Yaghmaeian, K.; Eskandari, M. Preparation, characterization and adsorption potential of the NH4Cl-induced activated carbon for the removal of amoxicillin antibiotic from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 217, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Zhang, P.; Seredych, M.; Bandosz, T.J. Removal of antibiotics from water using sewage sludge- and waste oil sludge-derived adsorbents. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4081–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccar, R.; Sarra, M.; Bouzid, J.; Feki, M.; Blánquez, P. Removal of pharmaceutical compounds by activated carbon prepared from agricultural by-product. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.J.; Theydan, S.K. Microporous activated carbon from Siris seed pods by microwave-induced KOH activation for metronidazole adsorption. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 99, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouretedal, H.R.; Sadegh, N. Effective removal of Amoxicillin, Cephalexin, Tetracycline and Penicillin G from aqueous solutions using activated carbon nanoparticles prepared from vine wood. J. Water Process. Eng. 2014, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camel, V. Solid phase extraction of trace elements. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2003, 58, 1177–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Cao, X.; Lu, D.; Luo, F.; Shao, W. Preparation and evaluation of orange peel cellulose adsorbents for effective removal of cadmium, zinc, cobalt and nickel. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 317, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, L.; Xueyi, G.; Ningchuan, F.; Qinghua, T. Adsorption of Cu2+ and Cd2+ from aqueous solution by mercapto-acetic acid modified orange peel. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2009, 73, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, R. Binding of divalent cations to oligomeric fragments of pectin. Carbohydr. Res. 1987, 160, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malovíková, A.; Kohn, R. 702 Binding of Cadmium Cations to Pectin. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1982, 47, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.G.; Iqbal, M.; Widmer, W.; Haven, A.S.N.W.W. Biosorption Properties of Citrus Peel Derived Oligogalac-turonides, Enzyme-modified Pectin and Peel Hydrolysis Residues. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 2008, 5, 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Haven, W. A Refereed Paper Production of Narrow-Range Size-Classes of Polygalacturonic Acid Oligomers. Proc. Fla. State Hortic. Soc. 2005, 118, 406–409. [Google Scholar]

- Joye, D.; Luzio, G. Process for selective extraction of pectins from plant material by differential pH. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 43, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, V.O.; Trilestari, K.; Sunarso, J.; Indraswati, N.; Ismadji, S. Recent progress on biosorption of heavy metals from liquids using low cost bio-sorbents: Characterization, biosorption parameters and mechanism studies. Clean Soil Air Water 2008, 36, 937–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Yun, Y.S. Bacterial bio-sorbents and biosorption. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 266–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, C. Biosorption of heavy metals by Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2006, 24, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahvi, A.H. Application of agricultural fibers in pollution removal from aqueous solution. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suryavanshi, U.; Shukla, S.R. Adsorption of Pb2+ by Alkali-Treated Citrus limetta Peels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 11682–11688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Schiewer, S. Biosorption of Cadmium(II) Ions by Citrus Peels in a Packed Bed Column: Effect of Process Pa-rameters and Comparison of Different Breakthrough Curve Models. Clean Soil Air Water 2011, 39, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Schiewer, S. Effect of Competing Cations (Pb, Cd, Zn, and Ca) in Fixed-Bed Column Biosorption and Desorption from Citrus Peels. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, K.N.; Inoue, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Makino, K.; Miyajima, T. Adsorptive separation of arsenate and arsenite anions from aqueous medium by using orange waste. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4945–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondhalekar, S.C.; Shukla, S.R. Equilibrium and kinetics study of uranium(VI) from aqueous solution by Citrus limetta peels. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2014, 302, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskheli, M.I.; Memon, S.Q.; Parveen, S.; Khuhawar, M.Y. Citrus paradisi: An Effective bio-adsorbent for Arsenic(V) Remediation. Pak. J. Anal. Environ. Chem. 2014, 15, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Khaskheli, M.I.; Memon, S.Q.; Siyal, A.N.; Khuhawar, M.Y. Use of Orange Peel Waste for Arsenic Remediation of Drinking Water. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2011, 2, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gönen, F. Adsorption study on orange peel: Removal of Ni(II) ions from aqueous solution. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.B.P.; Aguilar, M.I.; Ortuño, J.F.; Meseguer, V.F.; Sáez, J.; Llorens, M. Biosorption of Zn(II) by orange waste in batch and packed-bed systems. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, F.A.; Lima, I.S.; Lima, É.C.; Airoldi, C.; Gushikem, Y. Use of Ponkan mandarin peels as bio-sorbent for toxic metals uptake from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Sattar, J.A. Toxic Metal Pollution Abatement Using Sour Orange Biomass. J. Al-Nahrain Univ. Sci. 2013, 16, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torab-Mostaedi, M. Biosorpcija lantana i cerijuma iz vodenih rastvora pomoću kore mandarine (Citrus reticulata): Ravnotežna, kinetička i termodinamička ispitivanja. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2013, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, F.A.; Mazzocato, A.C.; Jacques, R.A.; Dias, S.L.P. Ponkan peel: A potential bio-sorbent for removal of Pb(II) ions from aqueous solution. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 40, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Marín, A.; Ballester, A.; González, F.; Blázquez, M.; Muñoz, J.; Sáez, J.; Zapata, V.M. Study of cadmium, zinc and lead biosorption by orange wastes using the subsequent addition method. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 8101–8106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, N.M.; Sapkal, R.S. Chromium(Vi) Removal By Using Orange Peel Powder in Batch Adsorption. Int. J. Chem. Sci. Appl. 2014, 5, 2278–6015. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C.M.; Dweck, J.; Viotto, R.S.; Rosa, A.H.; de Morais, L.C. Application of orange peel waste in the production of solid biofuels and bio-sorbents. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 196, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njikam, E.; Schiewer, S. Optimization and kinetic modeling of cadmium desorption from citrus peels: A process for bio-sorbent regeneration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 213–214, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowmya Lakshmi, K.B.; Munilakshmi, N. Adsorptive removal of colour from aqueous solution of disazo dye by using organic adsorbents. Int. J. Chem. Technol. Res. 2016, 9, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Lasheen, M.R.; Ammar, N.S.; Ibrahim, H.S. Adsorption/desorption of Cd(II), Cu(II) and Pb(II) using chemically modified orange peel: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Solid State Sci. 2012, 14, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaria, A.; Schiewer, S. Assessment of biosorption mechanism for Pb binding by citrus pectin. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 63, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.K.; Inoue, K.; Ghimire, K.N.; Ohta, S.; Harada, H.; Ohto, K.; Kawakita, H. The adsorption of phosphate from an aquatic environment using metal-loaded orange waste. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 312, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.-C.; Guo, X. Characterization of adsorptive capacity and mechanisms on adsorption of copper, lead and zinc by modified orange peel. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandina, S. Removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution using chemically modified orange (citrus cinensis) peel. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 2013, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Minocha, A.K.; Sillanpää, M. Adsorptive removal of cobalt from aqueous solution by utilizing lemon peel as bio-sorbent. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 48, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.V.T.M.; Diniz, K.M.; Massocatto, C.L.; Tarley, C.R.T.; Caetano, J.; Dragunski, D.C. Removal of Pb (II) from aqueous solution with orange sub-products chemically modified as biosorbent. BioResources 2012, 7, 2300–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaso, P. Adsorption of Copper Using Pomelo Peel and Depectinated Pomelo Peel. J. Clean Energy Technol. 2014, 2, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schiewer, S.; Iqbal, M. The role of pectin in Cd binding by orange peel bio-sorbents: A comparison of peels, depectinated peels and pectic acid. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiewer, S.; Patil, S.B. Modeling the effect of pH on biosorption of heavy metals by citrus peels. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 157, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Shukla, S.R. Adsorptive removal of cobalt ions on raw and alkali-treated lemon peels. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, M.; Evans, A.; Worthington, M.J.H.; Albuquerque, I.S.; Slattery, A.D.; Gibson, C.; Campbell, J.; Lewis, D.A.; Bernardes, G.; Chalker, J.M. Sulfur-Limonene Polysulfide: A Material Synthesized Entirely from Industrial By-Products and Its Use in Removing Toxic Metals from Water and Soil. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1714–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namasivayam, C.; Muniasamy, N.; Gayatri, K.; Rani, M.; Ranganathan, K. Removal of dyes from aqueous solutions by cellulosic waste orange peel. Bioresour. Technol. 1996, 57, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, A.; El Nemr, A.; El-Sikaily, A.; Abdelwahab, O. Treatment of artificial textile dye effluent containing Direct Yellow 12 by orange peel carbon. Desalination 2009, 238, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Sharif, M.; Iqbal, M. Application potential of grapefruit peel as dye sorbent: Kinetics, equilibrium and mechanism of crystal violet adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Microwave assisted preparation of activated carbon from pomelo skin for the removal of anionic and cationic dyes. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 173, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayarajan, M.; Arunachala, R.; Annadurai, G. Use of Low Cost Nano-porous Materials of Pomelo Fruit Peel Wastes in Removal of Textile Dye. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 5, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Kumar, E.; Minocha, A.K.; Jeon, B.-H.; Song, H.; Seo, Y.-C. Removal of Anionic Dyes from Water usingCitrus limonum(Lemon) Peel: Equilibrium Studies and Kinetic Modeling. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, H.N.; Akhtar, N.; Saleem, N. Adsorptive Removal of Methylene Blue by Low-Cost Citrus sinensis Bagasse: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Characterization. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2011, 37, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučić, D.; Miljanić, S.; Rožić, M. Sorption of Methylene Blue onto Orange and Lemon Peel. Holist. Approach Environ. 2011, 1, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales, E.; Meijide, J.; Tavares, T.; Pazos, M.; Sanromán, M.A. Grapefruit peelings as a promising bio-sorbent for the removal of leather dyes and hexavalent chromium. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 101, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, B.H.; Mahmoud, D.; Ahmad, A.L. Sorption of basic dye from aqueous solution by pomelo (Citrus grandis) peel in a batch system. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2008, 316, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.R. Adsorption of Erichrome black T from aqueous solutions on activated carbon prepared from mosambi peel. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Sanit. 2014, 6, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Mafra, M.R.; Igarashimafra, L.; Zuim, D.R.; Vasques, É.C.; Ferreira, M.A. Adsorption of remazol brilliant blue on an orange peel adsorbent. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, M.D.; Nikolić, I.R.; Milutinović, M.D.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.I.; Šiler-Marinković, S.S.; Antonović, D.G. Iskorišćenje sirovog otpada iz restorana za adsorpciju boja. Hem. Ind. 2015, 69, 667–677. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, N.A.; Ali, A.A.; Salmiati; Hussain, N.; Muhamad, M.S.; Kristanti, R.; Hadibarata, T. Removal of Remazol Brilliant Blue R from Aqueous Solution by Adsorption Using Pineapple Leaf Powder and Lime Peel Powder. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, O.S.; Ahmad, M.A.; Semire, B. Scavenging malachite green dye from aqueous solutions using pomelo (Citrus grandis) peels: Kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 56, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraj, R.; Namasivayam, C.; Kadirvelu, K. Orange peel as an adsorbent in the removal of Acid violet 17 (acid dye) from aqueous solutions. Waste Manag. 2001, 21, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, T.A.; Ali, M.I. Potential Application of Natural and Modified Orange Peel as an Eco‒friendly Adsorbent for Methylene Blue Dye. Iraqi J. Sci. 2016, 57, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lagergren, S. Zur Theorie der Sogenannten Adsorption Gelöster Stoffe. Sven. Vetensk. Handl. 1998, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process. Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, S.; Nasar, A. Adsorptive treatment of hazardous methylene blue dye from artificially contaminated water using cucumis sativus peel waste as a low-cost adsorbent. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 5, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levankumar, L.; Muthukumaran, V.; Gobinath, M. Batch adsorption and kinetics of chromium (VI) removal from aqueous solutions by Ocimum americanum L. seed pods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elovich, S.Y.; Larinov, O.G. Theory of Adsorption from Solutions of Non Electrolytes on Solid (I) Equation Adsorption from Solutions and the Analysis of Its Simplest Form, (II) Verification of the Equation of Adsorption Isotherm from Solutions. Izv. Akad. Nauk. SSSR 1962, 2, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, W.J.; Morris, J.C. Advances in water pollution research: Removal of biologically resistant pollutant from waste water by adsorption. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Water Pollution Symposium; Pregamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1962; Volume 2, pp. 231–266. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, I.A.W.; Hameed, B.H.; Ahmad, A.L. Equilibrium and kinetic studies on basic dye adsorption by oil palm fibre activated carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2007, 127, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H.M.F. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 385–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya, R.; Andersan, G.; Santoso, S.P.; Irawaty, W. Green Reduction of Graphene Oxide using Kaffir Lime Peel Extract (Citrus hystrix) and Its Application as Adsorbent for Methylene Blue. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, N.K.; Basu, S.; Sen, K.; Debnath, P. Potentiality of mosambi (Citrus limetta) peel dust toward removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solution: An optimization study. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Mashkoor, F.; Nasar, A. Development, characterization, and utilization of magnetized orange peel waste as a novel adsorbent for the confiscation of crystal violet dye from aqueous solution. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifzade, G.; Asghari, A.; Rajabi, M. Highly effective adsorption of xanthene dyes (rhodamine B and erythrosine B) from aqueous solutions onto lemon citrus peel active carbon: Characterization, resolving analysis, optimization and mechanistic studies. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 5362–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, A.H.; Al-Heetimi, D.T.A.; Mastuli, M.S. Biochar from orange (Citrus sinensis) peels by acid activation for methylene blue adsorption. Iran J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2019, 38, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- López-Manchado, M.; Arroyo, M. Effect of the incorporation of pet fibers on the properties of thermoplastic elastomer based on PP/elastomer blends. Polymer 2001, 42, 6557–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziabari, M.; Mottaghitalab, V.; Haghi, A.K. A new approach for optimization of electrospun nanofiber formation process. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Mishra, P.K.; Srivastava, P. Statistical optimization of the electrospinning process for chitosan/polylactide nanofabrication using response surface methodology. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 4262–4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Mondal, A.; Mishra, P.; Srivastava, P. A predictive model for the synthesis of polylactide from lactic acid by response surface methodology. ePolymers 2011, 11, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudamalla, P.; Pichiah, S.; Manickam, M. Responses of surface modeling and optimization of Brilliant Green adsorption by adsorbent prepared from Citrus limetta peel. Desalin. Water Treat. 2012, 50, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, S.K.; Lee, M.G. Response surface modeling for the adsorption of dye eosin Y by activated carbon prepared from waste citrus peel. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2018, 29, 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.G.; Kam, S.K. Study on the adsorption of antibiotics trimethoprim in aqueous solution by activated carbon prepared from waste citrus peel using box-behnken design. Korean Chem. Eng Res. 2018, 56, 568–576. [Google Scholar]

| Heavy Metals | Allowed Limits (WHO/EPA); mgL−1 | Source of Contamination | Adverse Effects on Health | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | 0.01 | Erosion of natural deposits, runoff from soil in orchards, glass and electronics manufacturing waste, tanneries | Skin damage, deformation of digits, cancer, deterioration of circulatory system | [48] |

| Beryllium | 0.004 | Metal refineries, coal burning, discharge from electrical, aerospace and metal finishing factories/industries | Gastrointestinal disorders | [49] |

| Cadmium | 0.005 | Corrosion of pipes and infrastructures, erosion of metal in refineries, battery waste, paints and dyes | Kidney damage, cancer of lungs, malfunctioning of vital organs, proteinuria | [50] |

| Chromium | 0.05–0.25 | Steel industries, metal finishing factories, pulp mills and corrosion of stainless steel pipes and infrastructures, tanneries | Allergy, dermatitis, hemolysis, kidney failure, carcinomas, mutagenic diseases | [51] |

| Copper | 1.0–1.3 | Corrosion of household utensils and artefacts, plumbing system, erosion from copper mines | Gastrointestinal disorders, abdominal irritation, liver and kidney damage | [52] |

| Lead | 0.005–0.015 | Battery waste, corrosion of pipes and plumbing system, solder joints, erosion from natural deposits | Retardation of growth in children, abnormality in mental health and physical growth, anemia, vomiting, kidney and liver damage, high blood pressure | [49,53] |

| Mercury | 0.002 | Erosion from natural deposits, discharge from refineries and factories, runoff from landfills, croplands | Hypersensitivity, fever, vomiting, neurological disorders | [49] |

| Selenium | 0.01–0.05 | Petroleum refineries, erosion from natural deposits and mining sites | Loss of hair and finger nails, red skin, numbness in fingers and toes, burns, circulatory system disorders | [49] |

| Zinc | 5 | Electroplating industry, galvanization of metals, motor oil, battery waste, hydraulic fluid, tire dust | Corrosive to skin and eyes, zinc pox, sweet taste, throat dryness, cough, weakness, generalized aching, chills, fever, nausea, vomiting | [54] |

| Dyes | Less than 1.0 ppm | Effluents from fiber and textile industries, paper and pulp industries, plastic industries, paint industries | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | |

| Fluoride | 1.5 | Fluoride deposits (rocks such as topaz, cryolite and fluorapatite, etc.) on earth. Electroplating, glass, ceramics, steel manufacturing and phosphate fertilizer production; semiconductor manufacturing factories, pharmaceutical companies, beryllium extraction plants, aluminum smelters, fertilizer manufacturing and mining industries | Dental and skeletal fluorosis, crippling | [55,56] |

| PACs (Pharmaceutically active compounds) | 50 ngL−1 to 0.1 μgL−1 | Pharmaceutical manufacturing plants, urban sewage, domestic hospital wastewaters, intensive livestock farming, liquid livestock manure production, sewage sludge from agricultural activities and effluents from sewage treatment plants | Genotoxicity and carcinogenicity, multiple drug resistance in pathogenic microorganisms, femaleness in males, tumor and vital organ failure in predatory birds | [49] |

| Adsorbent | Heavy Metals | Processing Method | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (Per Gram Adsorbent) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus limetta peels | Uranium | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 24 h; Grind, P.S. = 850 μm–1.2 mm; BAT—0.1 g BS in 40 mL MS; [U(VI)] = 250 mg/L; pH 2.0–7.0; CT—3 h; SRs—150 rpm | Maximum adsorption of 75.33 mg/g of bio-sorbent material at pH 4.0. Adsorbed species detected are UO22+, UO2OH+, (UO2)3(OH)5+, (UO2)2(OH)22+ | [100] |

| Citrus paradisi (Grapefruit) peels | Arsenic | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 6 h; Grind, P.S.=100–125 µm; Wash; Dry—333 K, 24 h BAT—0.2 g BS in 15–20 mL MS; [As(V)] = 0.1–50 mg/L; pH 4.0–7.0; CT—15 min–2 h; SRs—100–200 rpm | Maximum adsorption of 37.76 mg/g of bio-sorbent material at pH 4.0, 318 K. 76–94% removal in different polluted water sources | [101,102] |

| Orange peels | Nickel | Wash; Dry—373 K, 12 h; Grind, P.S. = 1.80 mm BAT—0.2 g BS in 100 mL MS; [Ni2+] = 10–200 mg/L; pH 5.0; SRs—200 rpm | 1.05–29.04 mg/g adsorbent from metal solution of concentration 10–200 mg/L. Maximum adsorbing capacity of 33.14% | [103] |

| Orange peels | Zinc | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, CW; Grind, P.S. = 0.15–1.5 mm BAT—0.2 g in 50 mL MS, [Zn2+] = 100 mg/L; pH 4.0–6.0; CT—3 h, stirring DAT—Acrylic column, 50 cm length; 2.2 cm diameter; 24 g peel pack, [Zn2+] = 20, 30, 40 mg/L, pH 4.0; FL—8.5 mL/min | BAT—0.664 mmol/g (75%) at pH 6.0 DAT—0.42–0.44 mmol/g | [104] |

| Citrus reticulata (Ponkan mandarin) peels | Nickel, Cobalt, Copper | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 24 h; Grind, P.S. ≤ 0.6 mm BAT—0.1 g BS in 25 mL MS, [M2+] = 0.01 M, pH = 4.8, Stirring—2 h DAT—50 cm length, 0.5 cm diameter, 1.0 g BS, [M2+] = 5 × 10−4 M, FS—3.5 mL/min, pH 4.8 | BAT—Nickel—1.92 mmol/g; Cobalt—1.37 mmol/g; Copper—1.31 mmol/g DAT—Nickel—1.85 mmol/g; Cobalt—1.35 mmol/g; Copper—1.30 mmol/g | [105] |

| Citrus aurantium (Bitter Orange) fruit parts | Cobalt | Wash; Sundry; Grind, P.S.= 250 µm BAT—2 g BS in 50 mL MS; [Co3+] = 5 mg/L; pH = 2.0, CT = 90 min; stirring | Flavedo = 57.99%; Albedo = 20.11%; Juice = 15.63%; Segment membrane = 20.90%; Seeds = 10.06% | [106] |

| Citrus reticulata Tangerine | Lanhanum Cerium | Wash; Dry 75–353 K, 24 h; Grind, P.S.= 355 µm BAT—0.5–3 g/l BS; [M3+] = 10–200 mg/L; pH 2.0–6.0; CT = 5–150 min; SRs—200 rpm; T 20–323 K | La(III)—154.86 mg/g Ce(III)—162.79 mg/g | [107] |

| Ponkan mandarin peels | Lead | Wash; Sun dry—7 d; Grind, P.S. ≤ 600 µm BAT—0.2 g BS in 25 mL MS; [M2+] = 0.5–1 g/L; pH 5.0; CT = 120 min; SRs—120 rpm; T 298 K | 112.1 mg/g | [108] |

| Orange waste | Binary systems Cd2+--Zn2+ Cd2+--Pb2+, Pb2+--Zn2+ | Wash; Dry; Grind, P.S.= 0.6–1.5 mm; BAT—0.4 g BS in 100 mL MS; [M12+–M22+] = 15–100 mg/L —15–25 mg/L added subsequently in 30 combinations. | Pb2+ > Zn2+ > Cd2+ Maximum uptake of 0.25 mmol/g adsorbent | [109] |

| Orange Peels | Chromium | Wash; Dry for 3 weeks; Grind BAT—2 g BS in 250 mL MS; [Cr(VI)] = 0.001 M; CT—5–360 min; Stir—180 rpm | Removal of up to 98% from synthetic chromium solution | [110] |

| Bio-Sorbent Modification by Heat/Enzyme/Chemical Treatment (BPT- Bio-Sorbent Pre-Treatment) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent | Heavy Metals | Processing Method | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (per Gram Adsorbent) | Ref. |

| Citrus limetta peels | Lead | Wash; Dry—343 K, 24 h; Grind, P.S. ≤ 1 mm BPT—10% isopropanol, 303 K, 24 h; 1 M citric acid, 303 K, 1 h, 353 K, 1 h; 0.1 M NaOH, 303 K, 6 h, 353 K, 0.5 h; oxidation with 50% H2O2, 353 K, 2 h at pH 11 BAT—0.1 g PTBS in 50 mL MS; [M2+] = 100 mg/L; pH = 4.0, T = 303 K; RSs—100 rpm; CT—6 h | 630 mg/g adsorbent. Cold alkali treatment increases adsorption by 87% (80% in first 15 min) | [96] |

| Citrus tamurana Citrus latifolia peels | Nickel, Cadmium, Lead from Oriza sativa (rice) | Wash; Sundry; Grind, P.S. = 250 µm; BPT—(a) Soaking in 1% w/v citric acid for 10 min, drained, dried at 423 K, 24 h CTBS (citric acid-treated BS) (b) CTBS heated to 673 K, powdered BSAC (BS active carbon) (c) BSAC treated with 1% w/v phosphoric acid, dried and sieved ACPA (active carbon treated with phosphoric acid) BAT—0.1 g CTBS, BSAC and ACPA added to 5 g of raw and rinsed rice, soaked in 250 mL DI with 2% NaCl at pH 6.3, 298 K, 1 h | Rice soaked with ACPA showed maximum reduction in heavy metal concentration Cd is reduced by 96.4%, Ni by 67.9%, Pb by 90.11% | [111] |

| Orange, Grapefruit peels | Cadmium | Wash; Dry; Grind, P.S. = 1–1.1 mm; BPT—Protonation —20 g BS in 1 L of 0.1 M HNO3, 240 min stirring, rinsed with DI, dried at 313 K for 740 min, protonated BS BAT—0.05 g protonated BS in 50 mL MS; [Cd2+] = 10–1000 mg/L (0.089–0.89 mM); CT—180 min; pH 5.0 | Adsorption of >90% Cd in 50 min. Desorption of the bio-sorbent material using 0.1 M HNO3 + 0.1 M Ca(NO3)2 shows 90% recovery in 60 min | [112] |

| Orange peels | Cadmium | Wash; Dry; Grind, P.S. = 1–1.1 mm BPT—Protonation—10 g BS in 500 mL 0.1 N HNO3, stirred for 4 h at 120 rpm, 298 K, rinsed with DI till pH 4.0, dried at 318 K for 12 h; PS = 1–2 mm DAT—Acrylic bed column; length 30 cm, diameter 1.3 cm; packed with 5.0 g Protonated BS; Bed height = 24–75 cm; [Cd2+] = 5–15 mg/L; FR = 2–15.5 mL/min; pH 5.5; T = 298 K | 0.40 mmol/g adsorbent | [97] |

| Orange juice residue waste | Arsenate, Arsenite | Wash; Vacuum dry; Grind, P.S. = 208 µm BPT—Step I—Decolorization: 10 g BS in 500 mL in 80% EtOH, stirred for 24 h, 298 K, filtered, washed with EtOH until colorless Vacuum-dried for 24 h, DBSG (de-colorized bio-sorbent gel) Step II—Cross-linking: 5.22 g DBSG, stirred with 200 mL DMSO for 24 h, 298 K; added 40 mL epichlorhydrin, stirred for 2 h; added 50 mL of 5 M NaOH, stood for 5 h at 323 K; cooled, filtered and washed with 70% EtOH, 0.5 M HCl, again with EtOH to pH 7.0; vacuum-dried, 24 h, cross-linked BS Step III—Phosphorylation: cross-linked BS soaked in 200 mL DMF overnight, filtered and immersed again in 200 mL DMF+ 5.04 g urea; added 3.1 g phosphoric acid drop-wise with constant stirring; stirred for 1 h. Temperature raised to 423 K and stirred for 2 h; cooled to RT, filtered, washed with 70% EtOH and DI until pH 7.0; washed with 0.1 M HCl and DI until pH 7.0; vacuum-dried for 2 days. Phosphorylated BS Step IV—Fe(III) loading: treated with Fe(III) solution of concentration 55.85 mg/L (= 1 mM), Fe(III)-loaded BS BAT—25 mg Fe(III)-loaded BS in 15 mL MS ([Arsenite/Arsenate] = 15 mg/L, 24 h, T = 303 K) DAT—column packed with 0.1 g Fe(III)-loaded BS and conditioned with pH 4 water overnight. [Arsenate/Arsenite] = 15 mg/L; FR—0.098 mL/min | Bio-sorbent pre-treatment and Fe(III) loading enables direct removal of arsenite and arsenate together, without oxidizing arsenite into arsenate DAT—0.91 mmol/g adsorbent; 99% removal of arsenic compared to 80% removal by cellulose control DAT—Maximum arsenic adsorbed on the packed bed = 1.1 mg. Elution with 0.1 M HCl recovers 0.62 mg arsenic (60% recovery) | [113] |

| Orange peels | Cadmium, Copper, Lead | Wash; Sun dry, 6 days; Grind, P.S. = 0.2 mm BPT—Protonation—10 g dried peel soaked in 1 L of 0.1 M HNO3, 6 h; filtered, rinsed with DI; sun-dried for 6 days. Protonated BS BAT—0.1–1 g protonated BS in 25 mL MS; [M2+] = 20 mg/L; CT—5–120 min; T 98 K; pH 5.0. Shaking at 200 rpm | Maximum adsorption of Pb = 73.53 mg/g; Cu = 15.27 mg/g; Cd = 13.7 mg/g. Pb(99.5%) > Cu(89.57%) > Cd(81.03%) at [M2+] = 20 mg/L and BS loading of 4 g/L Pb(96.3%) > Cu(93.3%) > Cd(85%) at [M2+] = 100–600 mg/L | [114] |

| Orange peels | Lead, Cadmium, Zinc | Wash; Dry; Grind, P.S. = 1–2 mm; BPT—Protonation—10 g BS in 500 mL 0.1 N HNO3, stirred for 4 h at 120 rpm, 298 K, rinsed with DI until pH = 4.0, dried at 318 K for 12 h; PS = 1–2 mm, protonated BS DAT—Acrylic column; length 30 cm, diameter—1.3 cm, 5 g protonated BS wet-packed. Feed concentration [Pb2+] = 10.36 mg/L; [Cd2+] = 5.62 mg/L; [Zn2+] = 3.27 mg/L. Total feed to the column = 20 L; FR = 9 mL/min, pH 5.0, T = 298 K | Pb (85 mg/g) > Cd (44 mg/g) > Zn (20 mg/g) | [98] |

| Citrus paradisi (Grapefruit) peels | Zinc, Nickel | Wash; Dry, 323 K until constant weight; Grind, P.S. 0.5–1.0 mm BPT—(a) Blocking of –COOH group—9.0 g BS suspended in 633 mL CH3OH, and 5.4 mL HCl; stirred at 100 rpm, 6 h. Centrifuged, washed, freeze-dried. (b) Blocking of –OH group—5.0 g BS suspended in 100 mL HCHO, stirred at 100 rpm, 6 h. Centrifuged, washed and freeze-dried BAT—100 mg BS in 100 mL MS; [M2+] = 300 mg/L, pH 5.0; CT = 120 min; SRs—100 rpm; 298 K | Native peel BS Ni2+—1.331 meq/g (84.73%) Zn2+—1.512 meq/g (92.46%) -COOH blocking reduces Ni2+ sorption by 78.57%, Zn2+ sorption by 73.31% -OH blocking reduces Ni2+ sorption by 22.63% and Zn2+ sorption by 28.54% | [69] |

| Citrus peel pectin | Lead | Citrus peel pectins (a) Low methoxylated (LM) pectin (methoxyl content 9%) and (b) high methoxylated (HM) pectin (methoxyl content 64%) BAT/KS—0.02 g BS in 200 mL MS; [M2+] = 0.1–1.0 mM; pH ≤ 5.0; T 294–298 K; CT—2–1440 min. Background electrolyte concentration—0.01 M NaNO3 | LM Pectin —0.86 mmol/g HM Pectin —0.87 mmol/g | [115] |

| Orange waste | Phosphate | Metal-loaded orange waste bio-sorbent: La(III)-loaded, Ce(III)-loaded and Fe (III)-loaded BS BAT—25 mg of La(III)- and Ce(III)-loaded BS and 60 mg of Fe(III)-loaded BS in 15 mL phosphate solution: (Phosphate) = 20–40 mg/L; pH = 7.5 for La(III)/Ce(III)-loaded BS and 3.0 for Fe(III)-loaded BS experiments. SRs = 140 rpm, 24 h, 303 K DAT—Glass column length—20 cm, diameter—0.8 cm; loaded with 150 mg of wet metal-loaded BS, (Phosphate) = 20–40 mg/L; FR = 7 mL/h | Phosphate adsorption by M—loaded BS (% removal) in BAT La(III)-loaded BS —13.84 mgP/g (98.5%) Ce(III)-loaded BS —14.0 mgP/g (98.8%) Fe (III)-loaded BS (99% removal) 13.63 mgP/g adsorbent in DAT | [116] |

| Orange waste | Nickel, Cobalt, Cadmium, Zinc | Wash; Dry, 323 K, 72 h. Ball mill—P.S. 0.1–0.2 mm; pore size—30.5 Å, BET surface area—128.7 m2/g BPT—Different treatments, viz., isopropyl alcohol, alkali saponification, acid oxidation to yield OP, PA, SNa, Sam/SCa, SOA, SCA, SPA; BAT—0.025 g BS in 15 mL MS; [M2+] = 0.001–0.01 M, CT—3 h | SPA—Ni2+—1.28 mol/Kg (95% increase) SPA—Co2+ —1.23 mol/Kg (178% increase) SCA—Cd2+—1.13 mol/Kg (60% increase) SOA—Zn2+—1.23 mol/Kg (130% increase) in comparison to raw orange peel (OP) Zn2+ → SCA>SNa>SOA>SPA>Sam>SCa>OP Cd2+ → SOA>SCA>SPA>SNa>Sam>SCa>OP Co2+/Ni2+ → SPA>SCA>SOA>SNa>Sam>SCa>OP | [85] |

| Orange peel | Lead, Zinc, Copper | Wash; Dry, 333.15 K; Grind: P.S. ≤ 0.45 mm –(OP); BET—0.828 m2/g BPT—100 g dried OP + 500 mL EtOH + 0.8 M NaOH + 0.8 M CaCl2; soak for 20 h, filter, wash until neutral pH—SCOP; BET—1.496 m2/g BAT—0.1 g BS (OP and SCOP) in 25 mL MS; [Pb2+] = 200 mg/L; [Zn2+] = 50 mg/L; [Cu2+] = 50 mg/L; SRs—120 rpm; CT—0–12 h; T 298 K | Adsorption capacity SCOP/OP (mg/g) Cu2+ → 70.73/44.28 Pb2+ → 209.8/113.5 Zn2+ → 56.18/21.25 Maximum adsorption was found at pH 5.5 Pb2+(99.4%) > Cu2+(93.7%) > Zn2+(86.6%) | [117] |

| Orange Peels | Chromium | Wash; Dry, 353 K; Grind, PS ≤ 200 µm BPT—100 g OP + 1 L of 0.1 M NaOH. Soak for 48 h; shake at 120 rpm, filter, wash, dry at 353 K—MOP (BET—0.8311 m2/g) BAT—0.2–5.0 g MOP in 50 mL MS; [Cr(VI)] = 100 mg/L; SRs—120 rpm; T 298 K; CT = 30 min–4 h; pH 1–8.0 | OP → 97.07 mg/g (39.9%) AOP → 139.0 mg/g (41.4%) Maximum adsorption was found at pH 2.0 and BS dose of 4 g/L in 180 min | [118] |

| Citrus lemon | Cobalt | Wash; Dry, 353 K, 24 h; Grind BPT—Thermal activation in air at 773 K, 1 h. Wash; dry, 373 K, 24 h. PS: BS 150–200 BAT—10 g/l BS; [Co2+] = 0–1000 mg/L; CT—10 h; SRs—200 rpm; pH 6.0 | 22 mg/g adsorbent | [119] |

| Orange waste Peel (OP), Bagasse (OB), Peel-bagasse (OPB) | Lead | Wash; Dry, 333.15 K; Grind, Sieve—BS—100-mesh BPT—1 g BS + 20 m 0.1 M NaOH, agitation—2 h; Wash, dry—328 K, 24 h. 1 g modified BS + 8.3 mL 1.2 M citric acid; agitation—30 min; filter; dry—328 K, 24 h; heat—393 K, 90 min; Wash; dry-328 K, 24 h BAT—0.5 g BS (OP, OB, OPB)/modified BS (OMP, OMB, OMPB) in 50 mL MS; [Pb2+] = 700 mg/L; pH 2.0–6.0; T = 303 K; CT—10–1440 min | Highest adsorption capacity shown by O-MP—84.53 mg/g OP—55.52 mg/g OB—46.90 mg/g OMB—80.19 mg/g OPB—32.55 mg/g OMPB—73.37 mg/g | [120] |

| Pomelo Peels | Copper | Wash; Dry, 343 K, 2–3 h. Grind, Sieve—(Pomelo Peel, PP) BPT—PP+ hot acidified water, pH 1.5, T = 388–393 K, 60 min; Filter. The solid peel residue after filtration is de-pectinated pomelo peel or DPP. Washed and dried at 343 K, 2–3 h; Grind: PS—0.42 mm. Filtrate contains pectin, precipitated by 95% EtOH. BAT—0.5 g BS (PP, DPP) + 100 mL MS; [Cu2+] = 25 mg/L; pH = 2.0–6.0; SRs—150 rpm; T 298 K; CT—180 min | Pomelo peel (PP)—19.7 mg/g De-pectinated pomelo peel (DPP)—21.1 mg/g | [121] |

| Lemon Peel | Cadmium | Wash; Dry—323 K; Grind: PS—0.5–1.0 mm—native peel (NP) BPT—(a) Protonation—10 g NP + 1.0 L of 0.1 M HCl, stir—6 h, 120 rpm; T 298 K; Filter, wash; Dry—323 K—protonated peels (PrP) (b) 10 g NP + 400 mL diluted HCl; pH 1.5 at 358 K; Stir—150 rpm—2 h; T 358 K. Filter: Filtrate is coagulated by 95% EtOH. Wash with 60%, 80% and 95% EtOH with a retention time of 30 min in each washing; vacuum dry—323 K—peel pectic acid (PP) (c) The solid residue left after pectic acid extraction is washed to remove all soluble sugars; vacuum dry—323 K—De-pectinated peels (DPP) BAT—50 mg BS (NP, PrP, PP, DPP) in 50 mL MS; [Co2+] = 100 mg/L (1.78 mequiv./L); pH 5.0; SRs—120 rpm; T 298 K; CT—180 min | Native peel (NP)→ 1.92 mequiv./g Protonated peels (PrP) → 2.44 mequiv./g De-pectinated peels (DPP)→ 1.75 mequiv./g Peel pectic acid (PP)→ 2.86 mequiv./g PP > PrP > NP > DPP | [122] |

| Orange peels, Lemon Peels, Lemon-based pectin peels (PP) | Cadmium | Native orange and lemon peels → Wash, Dry—311–313 K, 12 h; Grind BPT—Protonation—Lemon-based pectin peels are treated with 0.1 N HNO3, 6 h; Dry for 12 h, 311–313 K; Wash, Dry; Grind— PS: 0.7–0.9 mm—Protonated pectin peels (PPP) BAT—0.1 g BS (NOP, NLP, PPP) in 50 mL MS; [Co2+] = 10–700 mg/L; Shake—6 h; pH 3.0/5.0 | 0.7–1.2 mequiv./g (39–67 mg/g) | [123] |

| Citrus Pectin forms | Lead | Different forms of citrus pectins: GA oligomers—Large DP, medium DM and small DP size class GA oligomers (galacturonic acid) PME demethylated pectin (DM—50–80%) Pectin from peel residue Non-calcium-sensitive pectin Lyophilized BS from single-state fermentation of citrus peel (hydrolysis) BAT—50 mg BS in 50 mL MS; [Pb2+] = 0.5–1 g/l; pH 4.5; SRs—120 rpm; T 298 K; CT—6 h | Medium DP size class GA—380 mg/g, small DP size class GA—360 mg/g Large DP size class GA—300 mg/g PME demethylated pectin—220–270 mg/g Pectin from peel residue- 140 mg/g Non-calcium-sensitive pectin (NCSP)—200 mg/g Lyophilized BS from fermented citrus peel—100 mg/g | [89] |

| Orange Peels | Copper Cadmium | Wash; Dry—343 K, 24 h; Grind: PS—0.45 mm—native peel (NP) BPT—(a) 60 g NP + 300 mL 1% NaOH + 300 mL EtOH; RT; 24 h. Wash; Dry, 343 K, 24 h, DPOP (De-pigmented orange peels) (b) 30 g DPOP + 1 L 1% merceptoacetic acid, 12 h; Wash; Dry—343 K, 12 h. Grind—PS ≥ 0.45 mm BAT—50 mg BS in 10 mL MS; [M2+] = 0.05–1 g/l; SRs—120 rpm; CT—1.5 h; T 298 K, pH—5.0–7.0 | Cu2+—70.67 mg/g Cd2+—136.05 mg/g | [86] |

| Lemon Peel | Cobalt | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 24 h. Grind: PS= 1 mm—native peel (NP) BPT—10 NP + 100 mL 2% IPA, 0.1 N NaOH, 0.1 N HCl, 0.1 N H2SO4, 0.1 N HNO3; 4 h, 303 K, Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 24 h BAT—0.1 g BS in 50 mL MS; [Co2+] = 100 mg/L, T 303 K, SRs—150 rpm; CT—6 h | Native Peels—20.83 mg/g Modified Peels—35.7 mg/g | [124] |

| D-limonene | Mercury | Direct reaction between sulfur and D-limonene at (a) 443 K, 1 h; (b) 453 K, 50 mm Hg, 4 h; (c) 373 K < 1 mm Hg, 5 h | 55% removal | [125] |

| Adsorbent | Dye | Processing Method | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (Per Gram Adsorbent) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus reticulata | Acid Yellow-73 | Wash; Sun dry—7 days; Grind; Sieve through 50 ASTM mesh BPT-Soak—10% formaldehyde; air-dried—3 days; Oven-dried—353 K, 2 h BAT—1.0 g BS in 50 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 20 ppm; pH = 3.0; T = 323 K; SRs—100 rpm; CT—65 min; | 96.46 mg/g−1L−1 | [75] |

| Citrus sinensis | Congo Red, Rhodamine B, Procion orange | Wash; Sun dry—7 days; Grind—PS= 75–500 µm BAT—250 mg BS in 50 mL Congo Red dye solution; (Congo Red) = 60 mg/L; CT—20–90 min, SRs—140 rpm; T 302 K; pH 5.0 500 mg BS in 50 mL Rhodhamine B and Procion orange dye solutions; (Dye) = 10 mg/L; CT—20–90 min, SRs—140 rpm; T 302 K; pH 3.0 | Congo Red—22.4 mg/g; pH = 5.0 (76.6%) Procion orange—1.3 mg/g; pH = 3.0 (49%) Rhodamine B—3.22 mg/g; pH = 3.0 (38.43%) | [126] |

| Grapefruit peels | Methylene Blue | Wash; Sun dry—2 days; Grind—PS > 90 µm BPT- Carbonization—Treat with (a) BS_ 88% orthophosphoric acid (1: 3 ratio), (b) ZnCl2, or (c) 98% H2SO4 Heat at 723–823 K for 0.75–1.5 h, wash with NH4OH and H2O to neutral pH, Dry—12 h; Charred citrus peel (CCF); PS= 135 µm BAT—0.30–1.0 g CCF in 200 mL MB dye solution; (MB) = 20–100 mg/L; T 303 K; CT—8 h; pH 3.0–10.0 | 99.08% removal | [72] |

| Orange Peel | Direct Yellow-12 | Wash; Dry—423 K, 5 h; Grind BPT—Carbonization—3 kg dried orange peel + 2.5 L 98% H2SO4, Stand—2 h; Boil—3 h; Add to ice-cold water, filter; Dry—453 K, 2 h; immerse in 5.0 L of 5% NaHCO3, wash to neutral pH; Dry—423 K, 3 h; Grind ≤ 0.200 mm BAT—0.5 g in 100 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 75 mg/L; T 300 K; CT—2 h; pH 1.5–11.2; SRs—200 rpm | 96% removal | [127] |

| Grapefruit Peels | Crystal Violet | Wash; Dry—423 K, 5 h; Grind BAT—BS = 0.1–3 g/L of dye solution; (Dye) = 5–600 mg/L; pH 6.0; SRs—100 rpm; T 303 K; CT—60 min | 96% removal in 60 min. Maximum adsorption capacity = 254.16 mg/g | [128] |

| Pomelo Peel | Methylene Blue (Cationic Dye); Acid Blue (Anionic Dye) | Wash; Air dry; Grind-PS: 1.0–2.0 mm BPT—Microwave modification: BS + 1:1.25 by wt. NaOH. Microwave heating at 2.45 GHz, 800 W, 5 min; Wash with 0.1 M DI until neutral pH BAT—0.20 g Modified BS in 200 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 50–500 mg/L; SRs—120 rpm; T 303 K; CT—until equilibrium | Methylene Blue—501.1 mg/g Acid Blue—444.45 mg/g | [129] |

| Pomelo Peel | Congo Red | Wash; Dry—313 K, 48 h; Ball Mill-PS= 0.840 mm BAT—1.0–3.0 g BS in 1 L dye solution; (Dye) = 20–120 mg/L; T 276.15–333.15 K, pH 6.0–8.7; CT- 24 h | 0.75–1.08 mg/g | [130] |

| Citrus medica, Citrus aurentifolia, Citrus documana | Reactive Red 2 (Red M5B) | Wash; Dry—373–393 K, 24 h; Crush BPT—Carbonization—Heat at 773 K, N2; Liquid phase oxidation with 1 M HNO3; Wash, Dry—423 K, 12 h BAT—3 g BS in 100 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 20 mg/L; T 298 K; CT = 5–90 min; SRs—120 rpm; pH 3.0–10.0 | C. medica → 87% (0.5800 mg/g) C. aurentifolia → 85% (0.5667 mg/g) C. documana → 91% (0.6067 mg/g) | [70] |

| Citrus limonum | Methyl Orange, Congo Red | Wash; Dry—373 K, 24 h; Grind BPT—Heat at 773 K in air, 1 h; Wash; Dry—373 K, 24 h; PS-BSS 100–250 BAT—0.1 g BS in 10 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 0.3–0.45 mM; T 298 K; CT-until equilibrium; pH 5.5–6.5 | Methyl Orange → 50.3 mg/g Congo Red → 34.5 mg/g | [131] |

| Citrus sinensis bagasse | Methylene Blue | Wash; Dry—333 K, 72 h; Grind-PS: 0.25–0.75 mm BAT—0.1 g in 100 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 50 mg/L; CT—24 h; T 303 K; pH 7.0 | 96.4 mg/g | [132] |

| Orange Peel, Lemon Peel | Methylene Blue | Wash; Dry—353 K, 24 h; Grind-PS: <3.0 mm BAT—0.25 g in 25 cm3 dye solution; (Dye) = 50–1000 mg/dm3; T = 298 K; pH 2.0–3.0 | Orange Peel → 4.76–95.03 mg/g Lemon Peel → 4.41–92.1 mg/g | [133] |

| Grapefruit Peel | Leather Dye mixture: Sella Solid Blue, Special Violet, Derma Burdeaux, Sella Solid Orange | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 24 h; Grind-PS: <0.5 mm BPT—1.5 g BS + 150 mL of 1 M H2O2; Stirring—110 rpm, 24 h; Dry; Grind BAT—0.3–1.5 g BS in 50 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 100–400 mg/L; pH 5.5; T 298 K; SRs—120 rpm; CT = 24 h | Untreated Grapefruit peel BS →45% Modified Grapefruit peel BS → 80% Maximum capacity → 1.1003 meq/g Maximum uptake → 37.427 mg/g | [134] |

| Orange peel | Congo Red, Methyl Orange | Wash; Sun dry—72 h; Grind BPT—(a) BS + 1% NaOH, EtOH; Filter; Wash, Air dry —OP (removal of lignin and pigments) (b) 10 g OP + 100 mL DI; Stir and heat at 353 K; 120 min; Cool to RT, add N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone, stir for 5 min—NVP/OP copolymer (c) Transfer to glass tubes and irradiate with Gamma source—radiation dose (10–50 kGy); dose rate—1.46 kGy/h. Cross-linked NVP/OP hydrogel; Wash; Dry in air BAT—1:1 BS in 20 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 10–50 mg/L; T = 293–333 K; pH = 7.0 for Congo Red and 6.0 for Methyl Orange; CT (Congo Red) = 6000 min, (Methyl Orange) = 4000 min | Congo Red → 4.8–26 mg/g Methyl Orange → 4.6–10 mg/g | [73] |

| Citrus grandis | Methylene Blue | Wash; Dry—333.15 K, 48 h; Grind: PS= 0.5–1.0 mm BAT—0.20 g BS in 200 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 50–500 mg/L; pH 7.0; T 303 K; CT = 5.15 h; SRs—100 rpm | 344.83 mg/g at 303 K | [135] |

| Mosambi peels | Erichrome Black T | Wash; Sun dry; Grind; Dry—333 K, 24 h BPT—BS + Concentrated H2SO4 (1:1)- 24 h; Dry—378 K, 12 h; Wash with NaHCO3; Dry—378 K, Mosambi peel activated carbon (MPAC) | 93.8% | [136] |

| Citrus sinensis L. | Remazol Brilliant Blue | Wash, Dry—333 K, 24 h; Grind: Wash, Dry—333 K; PS = 44–1180 µm BAT—300 mg BS in 30 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 30, 100, 250 mg/L; SRs = 150 rpm; T 293–333 K; CT = 24 h | 11.62 mg/g | [137] |

| Citrus sinensis | Reactive Blue 19, Reactive Blue 49 | Wash; Dry; Grind—PS < 0.25 mm—BS BPT—(a) Immobilization: BS + sodium alginate (1:2). The resultant beads preserved in 0.02 M CaCl2 solution. Immobilized BS (b) 1 g BS + 5% glacial acetic acid. Wash after 1 h; Dry—343 K, 24 h. Acetic acid-treated BS BAT—0.5–1.5 g in 50 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 50–300 mg/mL; CT = 60–120 min; pH 2.0; T 303 K; SRs—100 rpm | Reactive Blue 19 BS → 37.45 mg/g Immobilized BS → 400.00 mg/g Acetic acid-treated BS → 75.19 mg/g Reactive Blue 49 BS → 135.16 mg/g Immobilized BS → 80.00 mg/g Acetic acid-treated BS → 232.56 mg/g | [66] |

| Citrus waste | Methylene Blue | Wash; Dry; Grind—383 K, 24 h; PS < 0.5 mm BAT—0.70 g in 100 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 5–60 mg/L; T 300 K, CT = 180 min; SRs—120 rpm | 3.2994 mg/g adsorbent at (Dye) = 50 mg/L. Maximum removal percentage → 49.35% at 60 mg/L | [138] |

| Lime Peel | Remazol Brilliant Blue R | Wash; Dry—T 378 K, 24 h; PS= 150 µm BAT—1–9 g BS in 50 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 10–50 mg/L; SRs—120 rpm; CT = 24 h; T 300 K | 73–95.89% removal. Adsorption capacity of 7.29–9.58 mg/g | [139] |

| Pomelo Peel | Malachite Green | Wash; Dry—T 393 K, overnight; Grind BPT—Carbonization—973 K, N2, 1 h; Char is soaked in KOH (1:1); Dry—423 K, overnight; Pyrolyze at 1073 K; N2 (150 cm3/min); At T = 1073 K, CO2 flow for 2 h; Cool to RT under N2 flux; Wash with 0.1 M HCl; Wash until neutral pH; BET—1357.21 m2/g BAT—0.2 g BS in 100 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 50–400 mg/g; T 293–333 K; CT = 4 h; SRs = 120 rpm; pH 3.0–10.0 | 178.48 mg/g Best result at pH = 8.0; T = 333.15 K 95.06% removal | [140] |

| Citrus reticulata | Indigo Caramine Dye | Wash; Sun dry, 7 d;ays Oven dry—T 343 K, 4 h BPT—(a) 100 g BS + 500 mL 20% formaldehyde, 3 h, FBS (b) 100 g BS + 10% urea solution, 3 h, UBS (a, b)—Filter, air dry; Oven dry, 343 K, 4 h; Grind: Sieve through 50-mesh ASTM = 297 µm BAT—0.3–3.0 g BS in 50 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 25 mg/L; T 293–343 K; CT = 10–70 min; pH 1.0–10.0; SRs—100 rpm | Dried Peel (BS) → 5.90 mg/g Formaldehyde-treated peel (FBS) → 14.79 mg/g Urea-treated peel (UBS) → 71.07 mg/g | [74] |

| Orange Peels | Acid Violet 17 | Wash; Sun dry—4 days; Grind; PS: 53–500 µm BAT—100–600 mg BS in 50 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 10 mg/L; pH 2.0–10.0; CT—80 min; T 303 K | 19.88 mg/g; 87% removal at pH = 2.0 and 100% removal at pH = 6.27 at adsorbent dose of 600 mg in 50 mL of 10 mg/L dye solution | [141] |

| Citrus limetta Peels | Methylene Blue | Wash; Sun dry—4 days; Oven dry—363 K, 24 h; Grind; Sieve, 80 BSS mesh; Wash; Dry—T 378 K, 4 h; Grind; PS= 80–200 BSS BAT—0.05 g in 25 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 25–250 mg/L; CT—3 h; pH 4.0 | 227.3 mg/g; 97–98% removal | [48] |

| Citrus sinensis Peels | C.I. Direct Blue 77 dye | Wash; Dry—T 378 K; Grind; PS = 75 µm BAT—5–30 mg in 100 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 50 mg/L; pH 2.0–12.0; SRs = 125 rpm; CT = 60 min | 59% removal; 9.43 mg/g | [113] |

| Orange peel | Methylene Blue | Wash; Dry—343 K, 5 h; Grind; PS= 75 µm, OP (dried orange peel) BPT—60 g OP + 250 mL of 0.1 M NaOH, 24 h; Filter; Wash; Dry—MOP (Modified OP) BAT—0.05 g in 25 mL dye solution; (Dye) = 35 mg/L; SRs = 160 rpm; pH 4.0; CT = 30 min; T 298–318 K | OP → 14.164 mg/g MOP → 18.282 mg/g | [142] |

| Citrus Peel as Adsorbent | Adsorbing Substance | T (Kelvin) | ΔG (kJ mol−1) | ΔH (kJ mol−1) | ΔS (J mol−1K−1) | Isotherm Fitted | Kinetics Model | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lemon peel | Cobalt | 298, 318 | −37.47, −38.56 | −21.2 | 54.61 | Langmuir model | Pseudo-second-order | [119] |

| Citrus sinensis (Musambi peel) | Methylene Blue dye (MB) | 303, 308, 313, 318, 323 | 0.76, 2.40, 2.90, 3.90, 4.40 | −51.9 | −0.18 | Langmuir model | Pseudo-second-order | [132] |

| Citrus sinensis (Orange peel) | Brilliant Blue dye (BB) | 303, 313, 323, 333 | −14.70, −16.11, −17.59, −18.32 | 22.82 | 124.20 | Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms | -- | [137] |

| Citrus sinensis (Orange peel) | Arsenic | 293, 298, 303, 308, 313, 318 | −30.18, −32.42, −33.35, −34.48, −35.06, −35.66 | 30.0 | −0.21 | Langmuir iotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [102,121] |

| Citrus grandis (Pomelo peel) | Malachite Green dye (MB) | 303, 318, 333 | −21.55, −22.89, −24.22 | 9.16 | 0.15 | Langmuir isotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [140] |

| Citrus maxima Pomelo peel | Copper | 298, 308, 318 | −5.38, −4.19, −3.49 | −32.18 | 0.09 | Langmuir isotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [121] |

| Citrus limetta (Musambi peel) | Methylene Blue dye (MB) | 293, 303, 313, 323 | −7.87, −9.38, −10.49, −12.41 | 35.13 | 146.70 | Langmuir isotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [48] |

| Citrus limetta (Musambi peel) | Fluoride | 298, 308, 318 | −0.69, −3.45, −5.61 | 72.58 | 246.22 | Langmuir isotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [56] |

| Citrus limetta (Musambi peel) | Chromium | 303, 313, 318, 323, 328 | −420.21, −725.16, −726.24, −2044.33, −1151.51 | 1.914 × 10−3 | 57.44 | D–R isotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [152] |

| rGO-Kaffir Lime Peel Extract | Methylene Blue dye (MB) | 303, 313, 333 | −5.98, −6.81, −8.47 | 19.15 | 82.93 | Langmuir isotherm | Pseudo-second-order | [151] |

| Magnetite Orange peel | Crystal Violet | 303, 313, 323, 333 | −5.92,−6.95, −8.02, −9.35 | 28.02 | 111.60 | Langmuir isotherm | Pseudo-second-order model | [153] |

| Lemon peels impregnated with phosphoric acid | Erythrosine-B (EB) Rhodamine-B (RB) | 298 298 | −3.19 −2.97 | 27.43 24.41 | 102.76 91.87 | Langmuir model | Pseudo-second-order model | [154] |

| Orange (citrus sinensis) peels by acid activation | Methylene Blue dye (MB) | 313, 323, 333 | −20.5, −12.9, −15.4 | 67.60 | 281.70 | Langmuir model | Pseudo-second-order model | [155] |

| Object of Experimental Design | Independent Variables | Response(s) | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters optimized for the preparation of adsorbent from citrus fruit peel | Weight ratio (citrus fruit peel to activating agent), temperature of carbonization | Operating parameters for carbonizing of citrus peel | Optimized conditions for carbonization of citrus fruit peel are: weight ratio of peel to activating agent (3:1) at temperature of 798 K, and time of carbonization was 0.75 h | [72] |

| Citrus fruit peel used in the removal of methylene blue (MB) dye | Initial concentration of MB, weight of CCFP and pH | Percentage removal of MB | 99.6225% MB removal at pH 3.64, weight of CCFP. Initial concentration of MB kept constant at 0.65 g and 20 mg/L. Prepared adsorbent is superior in terms of its porosity. | [72] |

| Citrus limetta peel dust used for removal of Cr(VI) | Initial concentration and pH of solution | Cr(VI) adsorption by musambi peel | Initial concentration 6.75, pH 4.29, dose 0.27 g/100 mL and contact time 56.40 min | [152] |

| Adsorption of Brilliant Green (BG) dye by adsorbent prepared from Citrus limetta peel | Temperature, pH, adsorbent dosage and contact time | Percentage removal efficiency of BG | The model validations as optimum levels of the process parameters to obtain the maximum adsorption of dye of 85.17% at 313 K, pH 9, at an adsorbent dose of 3.5 g/L of aqueous dye solution and contact time of 240 min | [160] |

| Adsorption of Eosin Y by the activated carbon (WCAC) prepared from waste citrus peel | Concentration of Eosin Y, temperature and the adsorbent dose | Adsorption of Eosin Y | Maximum dye uptake of 59.3 mg/g at the dye concentration of 50 mg/L, temperature 333 K and the adsorbent dose of 0.1056 g | [161] |

| Adsorption of antibiotic Trimethoprim studied by activated carbon prepared from waste citrus peel (WCAC) | Concentration of solution, pH, temperature and adsorbent dose | Adsorption efficiency of trimethoprim by WCAC | Maximum adsorption amount of TMP by WCAC calculated was 144.9 mg/g at 293 K | [162] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahato, N.; Agarwal, P.; Mohapatra, D.; Sinha, M.; Dhyani, A.; Pathak, B.; Tripathi, M.K.; Angaiah, S. Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-II: Bio-Sorbent Materials for Removal of Dyes, Heavy Metals and Toxic Chemicals from Polluted Water. Processes 2021, 9, 1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9091544

Mahato N, Agarwal P, Mohapatra D, Sinha M, Dhyani A, Pathak B, Tripathi MK, Angaiah S. Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-II: Bio-Sorbent Materials for Removal of Dyes, Heavy Metals and Toxic Chemicals from Polluted Water. Processes. 2021; 9(9):1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9091544

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahato, Neelima, Pooja Agarwal, Debananda Mohapatra, Mukty Sinha, Archana Dhyani, Brajesh Pathak, Manwendra K. Tripathi, and Subramania Angaiah. 2021. "Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-II: Bio-Sorbent Materials for Removal of Dyes, Heavy Metals and Toxic Chemicals from Polluted Water" Processes 9, no. 9: 1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9091544

APA StyleMahato, N., Agarwal, P., Mohapatra, D., Sinha, M., Dhyani, A., Pathak, B., Tripathi, M. K., & Angaiah, S. (2021). Biotransformation of Citrus Waste-II: Bio-Sorbent Materials for Removal of Dyes, Heavy Metals and Toxic Chemicals from Polluted Water. Processes, 9(9), 1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9091544