HER and OER Activity of Ti4O7@Ti Mesh—Fundamentals Behind Environmental Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Methods

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

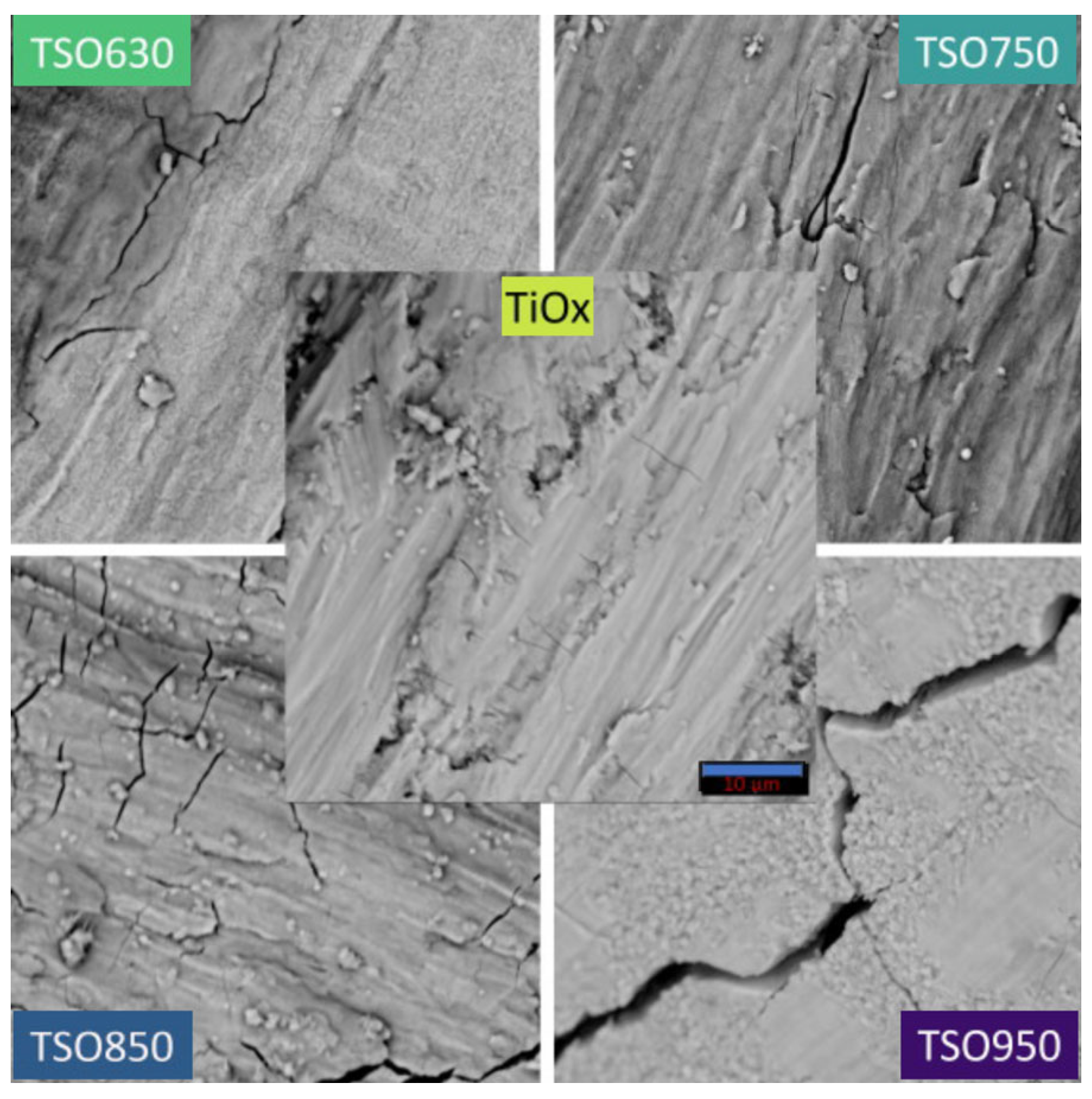

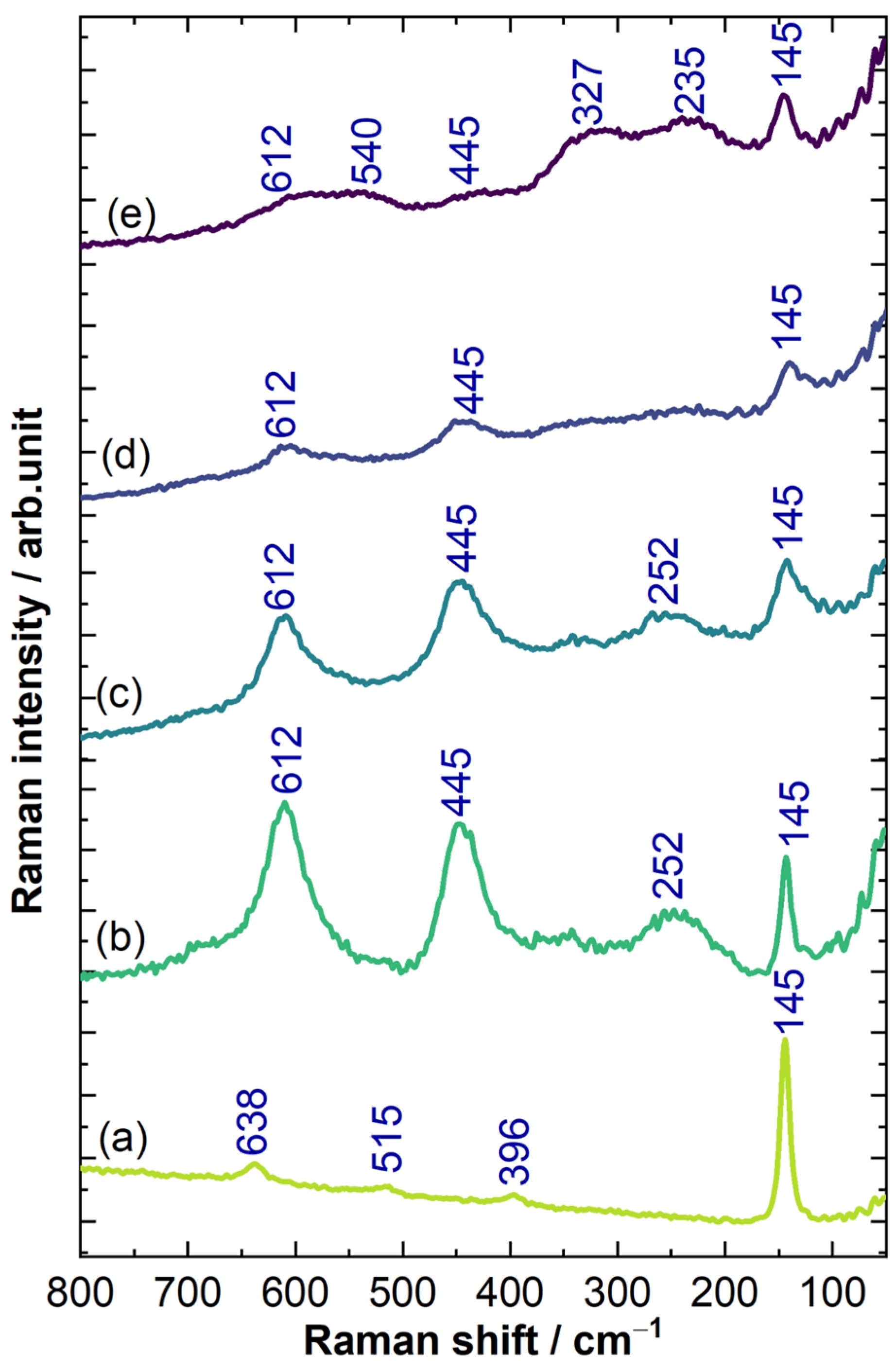

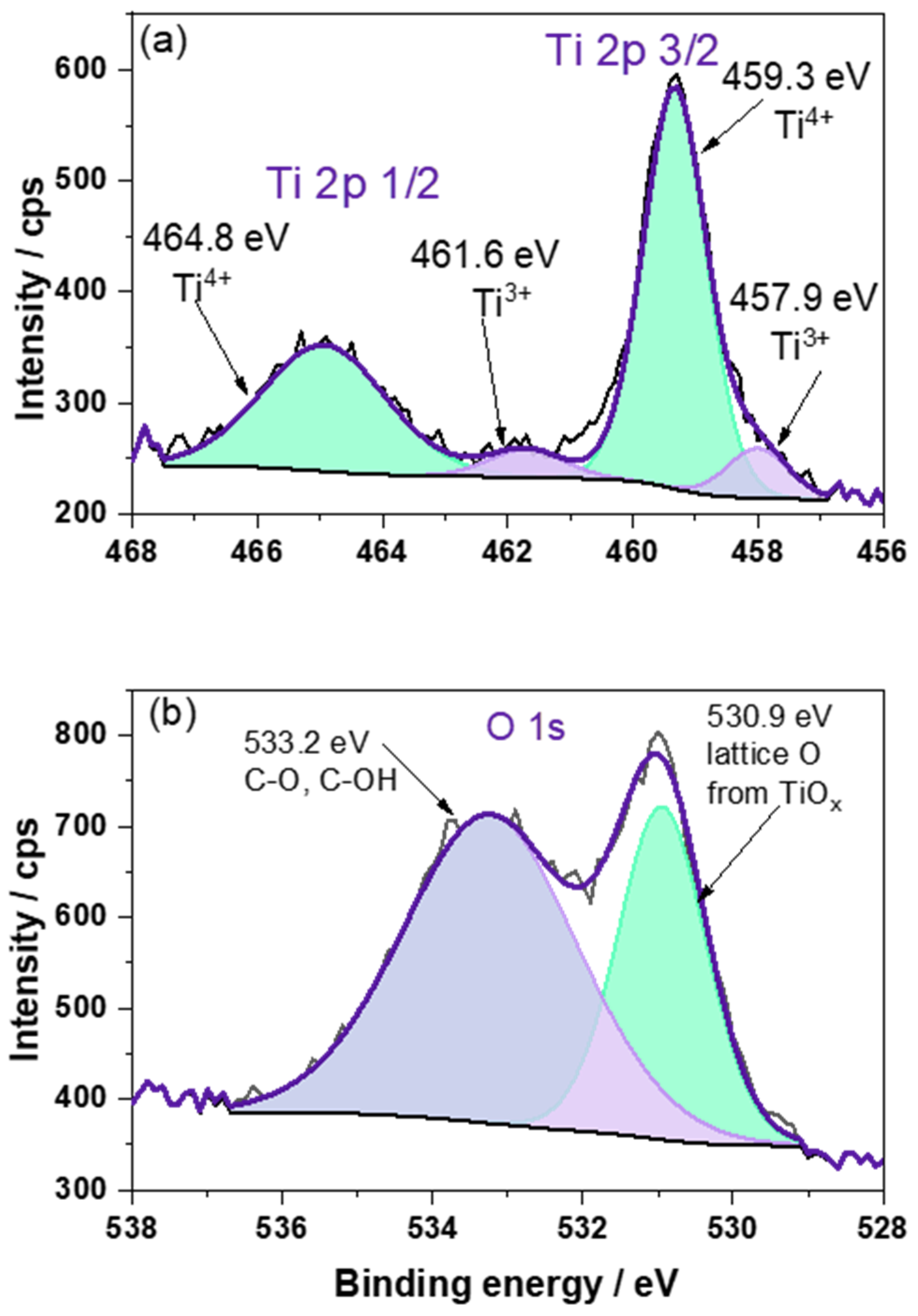

3.1. Characterization of TSO@Ti Mesh

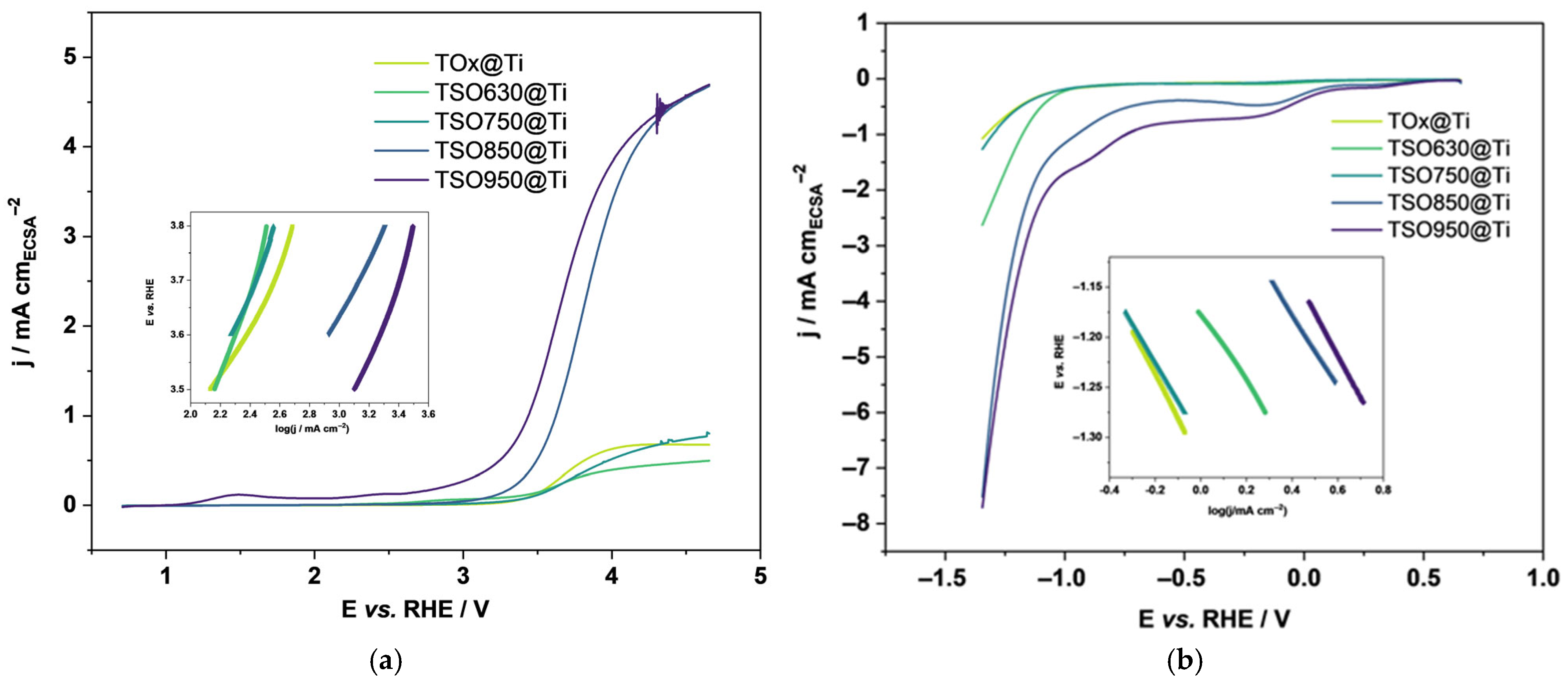

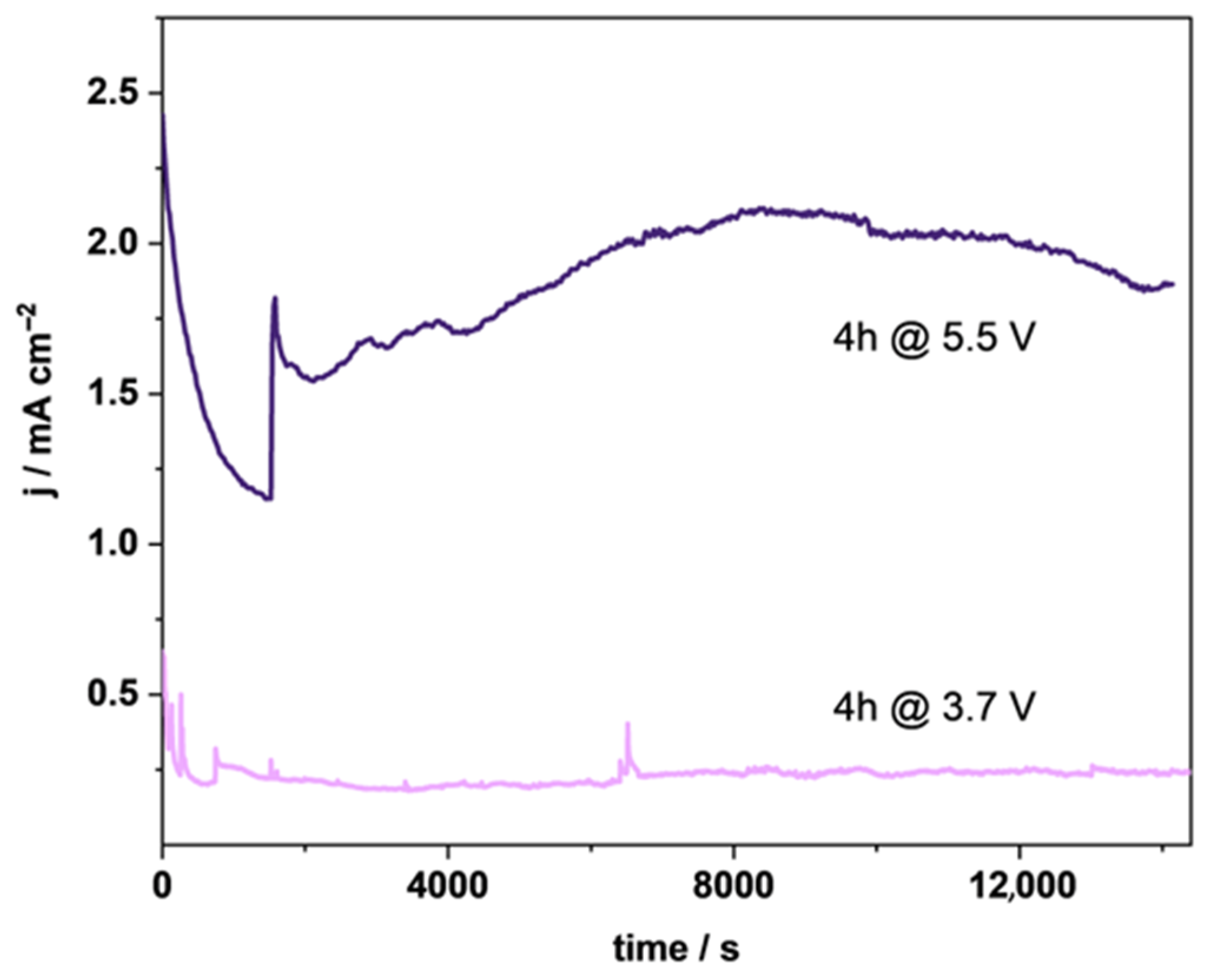

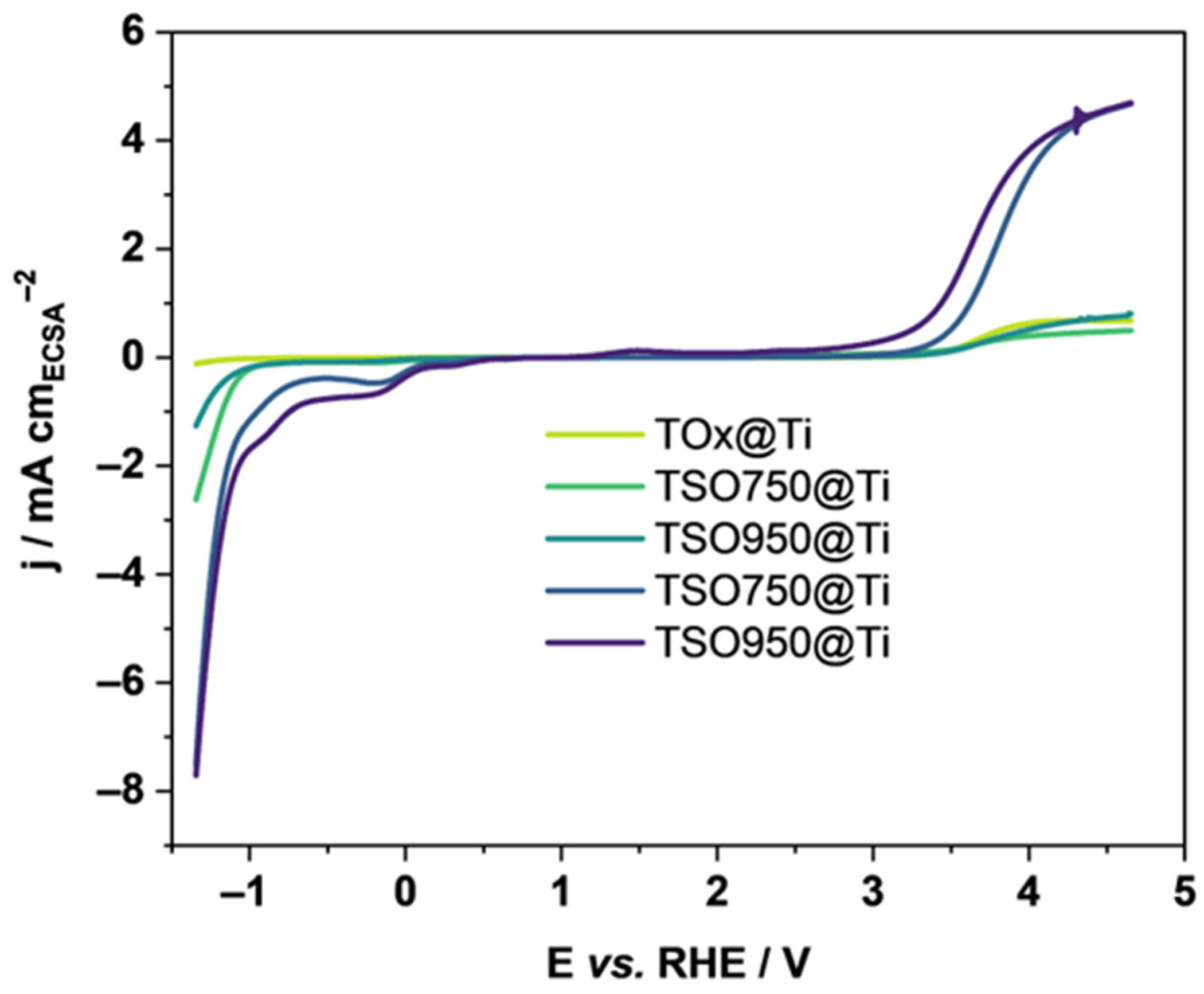

3.2. Electrochemistry of TSO@Ti Mesh

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, J.; Ning, Y.; Guo, K.; Jiao, W.; Chen, C.; Zhang, B.; Wu, X.; Zhao, J.; Lin, D.; Sun, S. Application of Metal-Organic Framework Materials in Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2025, 113, 115535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondaca-Medina, E.; García-Carrillo, R.; Lee, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ren, H. Nanoelectrochemistry in Electrochemical Phase Transition Reactions. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 7611–7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranković, M.; Gavrilov, N.; Jevremović, A.; Janošević Ležaić, A.; Rakić, A.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Ćirić-Marjanović, G. Highly Efficient Electrochemical Degradation of Dyes via Oxygen Reduction Reaction Intermediates on N-Doped Carbon-Based Composites Derived from ZIF-67. Processes 2025, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impemba, S.; Provinciali, G.; Filippi, J.; Caporali, S.; Muzzi, B.; Casini, A.; Caporali, M. Tightly Interfaced Cu2O with In2O3 to Promote Hydrogen Evolution in Presence of Biomass-Derived Alcohols. ChemNanoMat 2024, 10, e202400459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impemba, S.; Provinciali, G.; Filippi, J.; Salvatici, C.; Berretti, E.; Caporali, S.; Banchelli, M.; Caporali, M. Engineering the Heterojunction between TiO2 and In2O3 for Improving the Solar-Driven Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 63, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diglio, M.; Contento, I.; Impemba, S.; Berretti, E.; Della Sala, P.; Oliva, G.; Naddeo, V.; Caporali, S.; Primo, A.; Talotta, C.; et al. Hydrogen Production from Formic Acid Decomposition Promoted by Gold Nanoparticles Supported on a Porous Polymer Matrix. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 14320–14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A.; Diglio, M.; Impemba, S.; Venditto, V.; Vaiano, V.; Buonerba, A.; Sacco, O. Dual-Function Bare Copper Oxide (Photo)Catalysts for Selective Phenol Production via Benzene Hydroxylation and Low-Temperature Hydrogen Generation from Formic Acid. Catalysts 2025, 15, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oturan, M.A.; Aaron, J.-J. Advanced Oxidation Processes in Water/Wastewater Treatment: Principles and Applications. A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 2577–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, C.E.; Andaya, C.; Burant, A.; Condee, C.W.; Urtiaga, A.; Strathmann, T.J.; Higgins, C.P. Electrochemical Treatment of Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate: Insights into Mechanisms and Application to Groundwater Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 317, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Panizza, M. Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Pollutants for Wastewater Treatment. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 11, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousset, E.; Oturan, N.; Oturan, M.A. An Unprecedented Route of OH Radical Reactivity Evidenced by an Electrocatalytical Process: Ipso-Substitution with Perhalogenocarbon Compounds. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 226, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, R.; Ureta-Zañartu, M.S.; González-Vargas, C.; do Nascimento Brito, C.; Martinez-Huitle, C.A. Electrochemical Degradation of Industrial Textile Dye Disperse Yellow 3: Role of Electrocatalytic Material and Experimental Conditions on the Catalytic Production of Oxidants and Oxidation Pathway. Chemosphere 2018, 198, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duinslaeger, N.; Doni, A.; Radjenovic, J. Impact of Supporting Electrolyte on Electrochemical Performance of Borophene-Functionalized Graphene Sponge Anode and Degradation of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Water Res. 2023, 242, 120232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, A.F.; Balgis, R.; Ogi, T.; Iskandar, F.; Kinoshita, A.; Nakamura, K.; Okuyama, K. Highly Conductive Nano-Sized Magnéli Phases Titanium Oxide (TiOx). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.C.; Wills, R.G.A. The Continuing Development of Magnéli Phase Titanium Sub-Oxides and Ebonex® Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 6342–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.A.; Avvakumov, E.G.; Medvedev, A.Z.H.; Masliy, A.I. Ceramic Electrodes Based on Magneli Phases of Titanium Oxides. Sci. Sinter. 2007, 39, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Walsh, F.C.; Clarke, R.L. Electrodes Based on Magnéli Phase Titanium Oxides: The Properties and Applications of Ebonex® Materials. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1998, 28, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioroi, T.; Senoh, H.; Yamazaki, S.; Siroma, Z.; Fujiwara, N.; Yasuda, K. Stability of Corrosion-Resistant Magnéli-Phase Ti4O7-Supported PEMFC Catalysts at High Potentials. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, B321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Wang, J.; Ying, Z.; Cai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Gan, Y.; Huang, H.; Xia, Y.; Liang, C.; Zhang, W.; et al. Strong Sulfur Binding with Conducting Magnéli-Phase TinO2n−1 Nanomaterials for Improving Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5288–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Kundu, D.; Cuisinier, M.; Nazar, L.F. Surface-Enhanced Redox Chemistry of Polysulphides on a Metallic and Polar Host for Lithium-Sulphur Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialdone, O.; Randazzo, S.; Galia, A.; Filardo, G. Electrochemical Oxidation of Organics at Metal Oxide Electrodes: The Incineration of Oxalic Acid at IrO2–Ta2O5 (DSA-O2) Anode. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjenovic, J.; Sedlak, D.L. Challenges and Opportunities for Electrochemical Processes as Next-Generation Technologies for the Treatment of Contaminated Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11292–11302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Qiu, K. Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Formic Acid on Platinum Nanoparticle Electrode Deposited on the Nichrome Substrate. Electrochem. Commun. 2006, 8, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Chaplin, B.P. Fabrication and Characterization of Porous, Conductive, Monolithic Ti4O7 Electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 263, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Jing, Y.; Chaplin, B.P. Development and Characterization of Ultrafiltration TiO2 Magnéli Phase Reactive Electrochemical Membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Sohn, H.Y.; Mohassab, Y.; Lan, Y. Structures, Preparation and Applications of Titanium Suboxides. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 79706–79722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Folk, R.R.; Noftle, R.E.; Pletcher, D. Electron Transfer Reactions at Ebonex Ceramic Electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1989, 274, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, M.; Yano, T.; Tryba, B.; Mozia, S.; Tsumura, T.; Inagaki, M. Preparation of Carbon-Coated Magneli Phases TinO2n−1 and Their Photocatalytic Activity under Visible Light. Appl. Catal. B 2009, 88, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnović, V.; Ranković, M.; Jevremović, A.; Mijailović, N.R.; Nedić Vasiljević, B.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Gavrilov, N. Doping of Magnéli Phase—New Direction in Pollutant Degradation and Electrochemistry. Molecules 2025, 30, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Ye, J.; Qiu, W. Synthesis, Microstructural Characterization, and Electrochemical Performance of Novel Rod-like Ti4O7 Powders. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 704, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portehault, D.; Maneeratana, V.; Candolfi, C.; Oeschler, N.; Veremchuk, I.; Grin, Y.; Sanchez, C.; Antonietti, M. Facile General Route toward Tunable Magnéli Nanostructures and Their Use As Thermoelectric Metal Oxide/Carbon Nanocomposites. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9052–9061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhu, R. Fabrication of Ti4O7 Electrodes by Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Lett. 2014, 114, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsaka, T. Temperature Dependence of the Raman Spectrum in Anatase TiO2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1980, 48, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaor, D.A.H.; Sorrell, C.C. Review of the Anatase to Rutile Phase Transformation. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichon, L.; Rekik, H.; Arab, H.; Drogui, P.; El Khakani, M.A. High Photothermal Conversion Efficiency of RF Sputtered Ti4O7 Magneli Phase Thin Films and Its Linear Correlation with Light Absorption Capacity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Sarkar, S.; Mohanty, S.; Carlson, K. Modelling and Synthesis of Magnéli Phases in Ordered Titanium Oxide Nanotubes with Preserved Morphology. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, A.L.; Qu, W.; Wang, H.; Hui, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Magneli Phase Ti4O7 Electrode for Oxygen Reduction Reaction and Its Implication for Zinc-Air Rechargeable Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 5891–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, X. Electrochemical Oxidation of Phenol in Chloride Containing Electrolyte Using a Carbon-Coated Ti4O7 Anode. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 449, 142233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.S.C. Resolving Surface Chemical States in XPS Analysis of First Row Transition Metals, Oxides and Hydroxides: Sc, Ti, V, Cu and Zn. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 257, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhou, M.; Pan, Y.; Du, X.; Lu, X. Extremely Efficient Electrochemical Degradation of Organic Pollutants with Co-Generation of Hydroxyl and Sulfate Radicals on Blue-TiO2 Nanotubes Anode. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 257, 117902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, J.; Lee, W.; Ahn, Y.-Y.; Lee, H.; Cho, K.; Lee, J. Performance of Magnéli Phase Ti4O7 and Ti3+ Self-Doped TiO2 as Oxygen Vacancy-Rich Titanium Oxide Anodes: Comparison in Terms of Treatment Efficiency, Anodic Degradative Pathways, and Long-Term Stability. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 337, 122993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wei, F.; Chen, T.; Tang, J.; Yang, L.; Jia, H.; Li, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, B. A Novel Synthetic Strategy of Mesoporous Ti4O7-Coated Electrode for Highly Efficient Wastewater Treatment. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 26503–26512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Sirés, I. Electro-Fenton Process for the Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water. In Encyclopedia of Applied Electrochemistry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 696–702. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, F.; Krohn, H.; Kaiser, W.; Fryda, M.; Klages, C.P.; Schäfer, L. Boron Doped Diamond/Titanium Composite Electrodes for Electrochemical Gas Generation from Aqueous Electrolytes. Electrochim. Acta 1998, 44, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluđerović, M.; Savić, S.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Jovanović, A.Z.; Rakočević, L.; Vlahović, F.; Milikić, J.; Stanković, D. Samarium-Doped PbO2 Electrocatalysts for Environmental and Energy Applications: Theoretical Insight into the Mechanisms of Action Underlying Their Carbendazim Degradation and OER Properties. Processes 2025, 13, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipin, D.; Risch, M. Calculation of the Tafel Slope and Reaction Order of the Oxygen Evolution Reaction between PH 12 and PH 14 for the Adsorbate Mechanism. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2023, 3, e2100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Osorio, D.A.; Jaimes, R.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Lara, R.H.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J. The Kinetic Parameters of the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) Calculated on Inactive Anodes via EIS Transfer Functions: •OH Formation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, E3321–E3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapałka, A.; Fóti, G.; Comninellis, C. Determination of the Tafel Slope for Oxygen Evolution on Boron-Doped Diamond Electrodes. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yao, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, R.; Xu, Y.; Chu, Y.; Mao, X.; Zheng, H. Electrocatalytic Dehalogenation in the Applications of Organic Synthesis and Environmental Degradation. EcoEnergy 2024, 2, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Electrocatalytic Hydro-Dehalogenation of Halogenated Organic Pollutants from Wastewater: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2023, 234, 119810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xue, Y.; Dehoff, R.; Tsouris, C.; Taboada-Serrano, P. Hierarchically-Structured Ti/TiO2 Electrode for Hydrogen Evolution Synthesized via 3D Printing and Anodization. J. Energy Power Technol. 2020, 2, 007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasik, N.; Roda, D.; de Oliveira, M.A.; Silva Barros, B.; Kulesza, J.; Łapiński, M.; Świątek, H.; Ilnicka, A.; Klimczuk, T.; Szkoda, M. Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Catalyzed by Co-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Derivatives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Ling, Y.; Wang, S.; Pu, H.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Unraveling and Resolving the Inconsistencies in Tafel Analysis for Hydrogen Evolution Reactions. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bare, S.R.; Mallouk, T.E. Development of Supported Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Unitized Regenerative Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002, 149, A1092–A1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Yuan, T.; Ye, J. Recent Progress in Electrochemical Application of Magnéli Phase Ti4O7-Based Materials: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 14911–14944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislyi, A.; Moroz, I.; Guliaeva, V.; Prokhorov, Y.; Klevtsova, A.; Mareev, S. Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Pollutants in Aqueous Solution Using a Ti4O7 Particle Anode. Membranes 2023, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | ECSA/ cm2 | Tafel Slopes | Onset Potential/V | Rct (EIS)/Ohm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OER/mV dec−1 | HER/mV dec−1 | ||||

| TSO950@Ti | 1.15 | 577 ± 6 | 370 ± 3 | 3.18 | 29.1 |

| TSO850@Ti | 1.10 | 418 ± 7 | 361 ± 2 | 3.20 | 29.4 |

| TSO750@Ti | 5.22 | 630 ± 7 | 385 ± 2 | 3.25 | 29.0 |

| TSO630@Ti | 7.35 | 794 ± 3 | 341 ± 2 | 3.29 | 27.9 |

| TiOx@Ti | 9.30 | 640 ± 8 | 439 ± 6 | 3.28 | 46.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ranković, M.; Rakočević, L.; Jevremović, A.; Nedić Vasiljević, B.; Janošević Ležaić, A.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Gavrilov, N. HER and OER Activity of Ti4O7@Ti Mesh—Fundamentals Behind Environmental Application. Processes 2026, 14, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030518

Ranković M, Rakočević L, Jevremović A, Nedić Vasiljević B, Janošević Ležaić A, Bajuk-Bogdanović D, Milojević-Rakić M, Gavrilov N. HER and OER Activity of Ti4O7@Ti Mesh—Fundamentals Behind Environmental Application. Processes. 2026; 14(3):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030518

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanković, Maja, Lazar Rakočević, Anka Jevremović, Bojana Nedić Vasiljević, Aleksandra Janošević Ležaić, Danica Bajuk-Bogdanović, Maja Milojević-Rakić, and Nemanja Gavrilov. 2026. "HER and OER Activity of Ti4O7@Ti Mesh—Fundamentals Behind Environmental Application" Processes 14, no. 3: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030518

APA StyleRanković, M., Rakočević, L., Jevremović, A., Nedić Vasiljević, B., Janošević Ležaić, A., Bajuk-Bogdanović, D., Milojević-Rakić, M., & Gavrilov, N. (2026). HER and OER Activity of Ti4O7@Ti Mesh—Fundamentals Behind Environmental Application. Processes, 14(3), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030518