Investment Deficit Measurement of Flexible Generation for Consuming Renewables

Abstract

1. Introduction

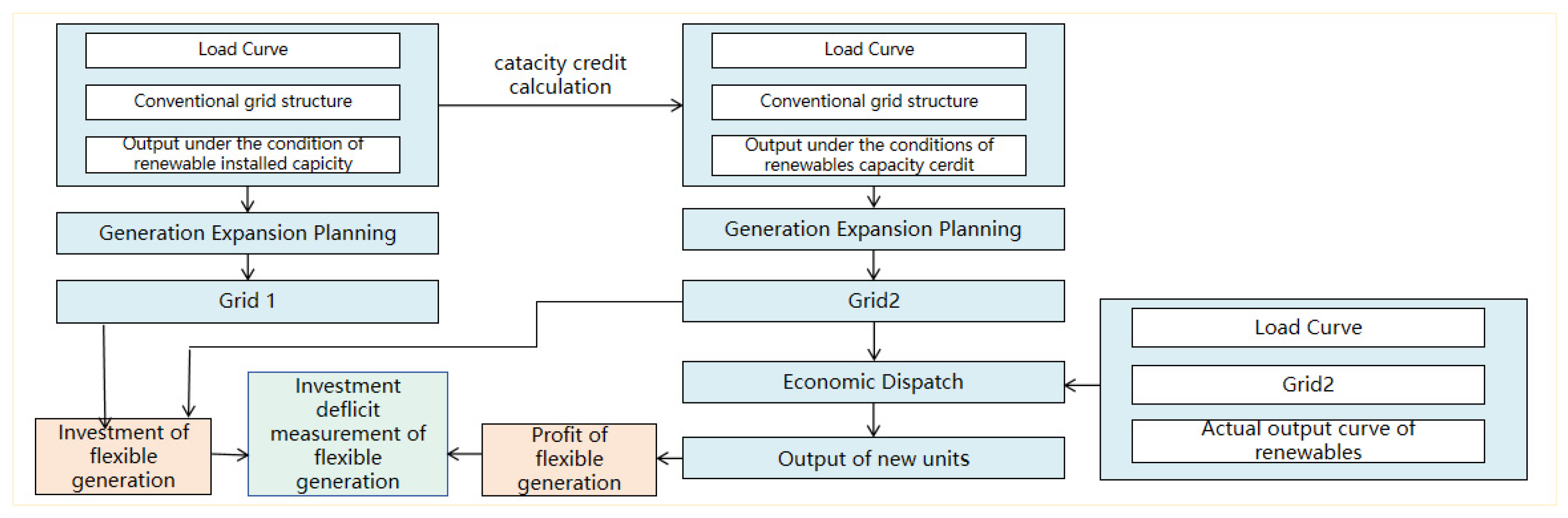

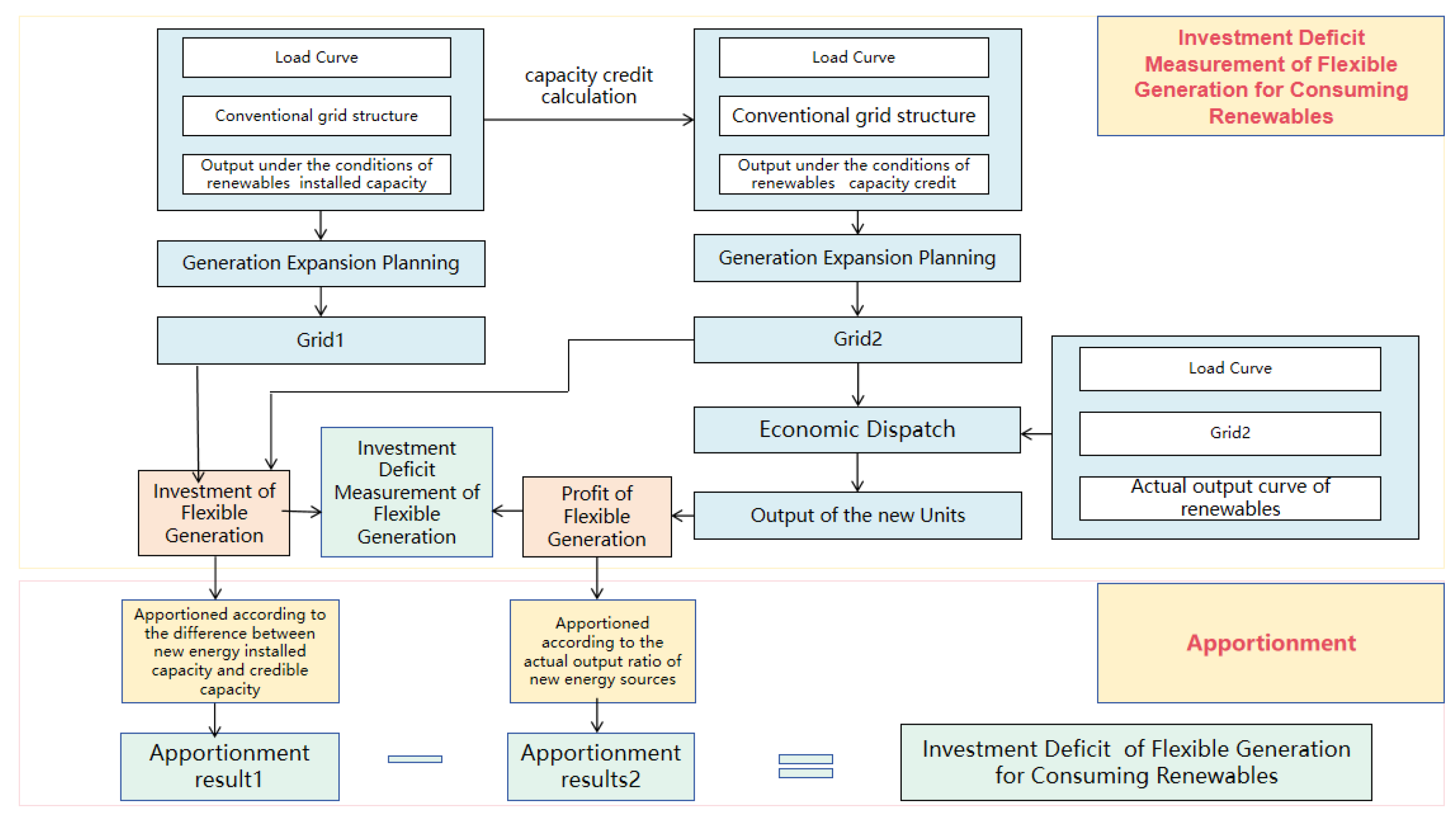

- The reasons for the investment cost gap in renewables’ flexible generation are analyzed, and, based on this, a framework for the investment deficit of flexible generation for consuming of renewables is constructed.

- A model to measure the investment deficit of flexible generation for consuming of renewables was built, including a power planning model, an economic dispatch model, and an investment deficit calculation model of flexible generation for the consumption of renewables.

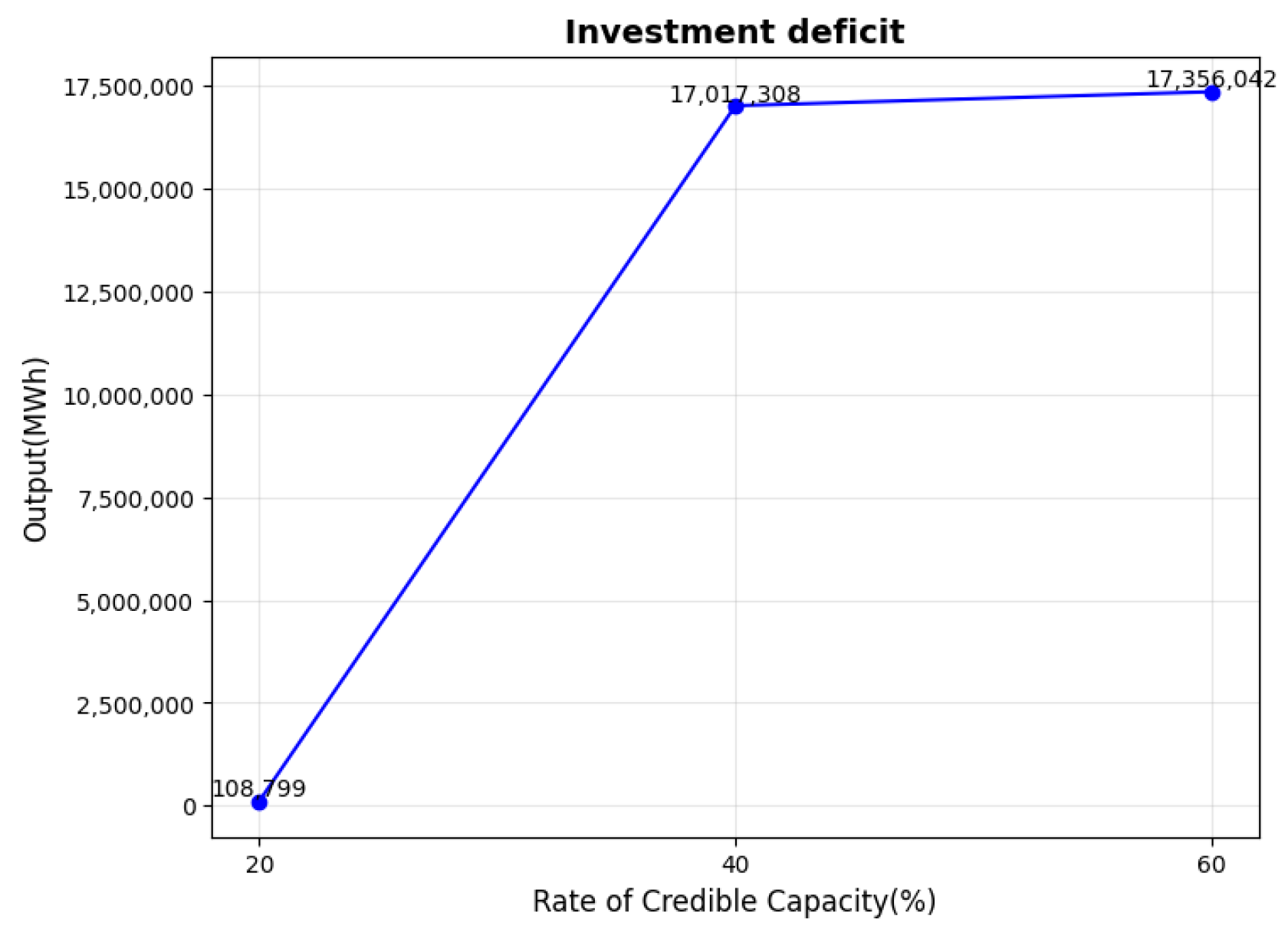

- The IEEE system was used to calculate the investment deficit of flexible generation for the consumption of renewables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Investment Gap for Flexible Generation for Renewables

2.1.1. Analysis of the Investment Gap for Flexible Generation for Renewables

2.1.2. Assessment Framework of the Investment Gap for Flexible Generation for Renewables

2.2. Assessment Method of the Investment Gap for Flexible Generation for Renewables

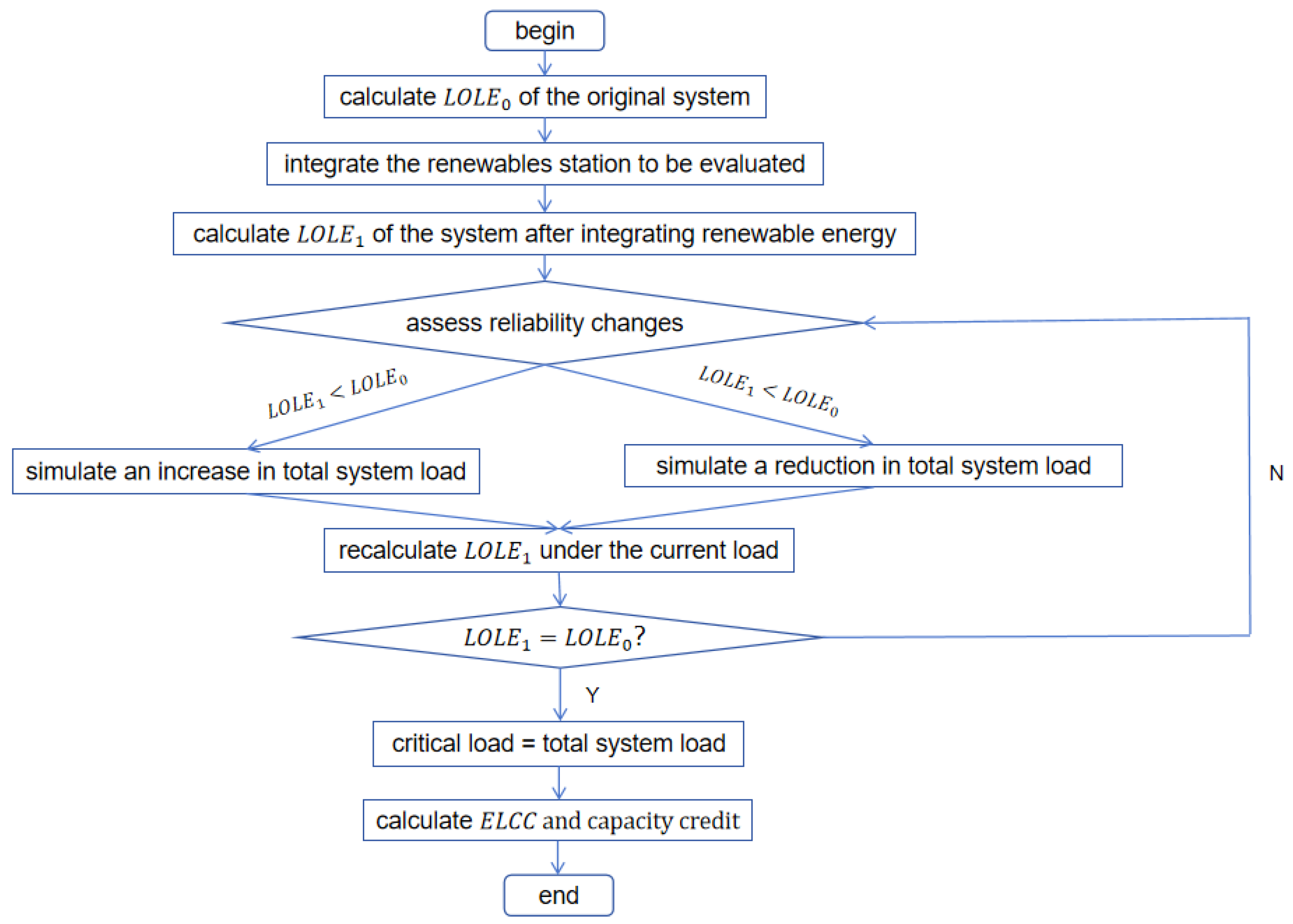

2.2.1. Effective Load Carrying Capability

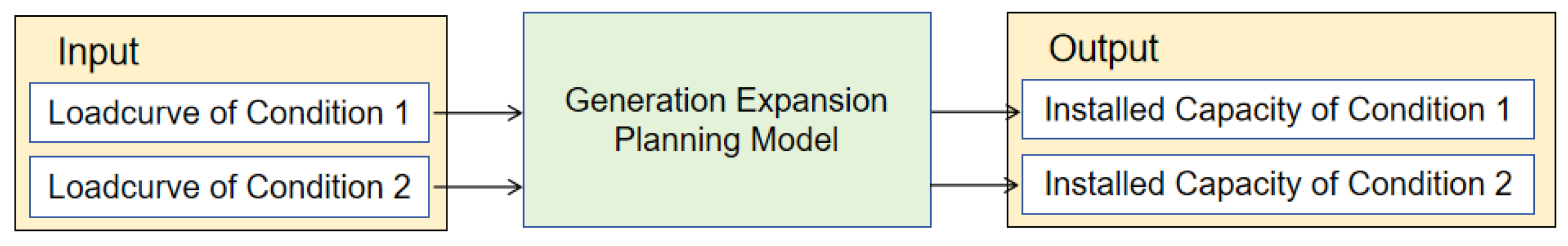

2.2.2. Generation Expansion Planning Model

- Objective Function:

- 2.

- Constraint:

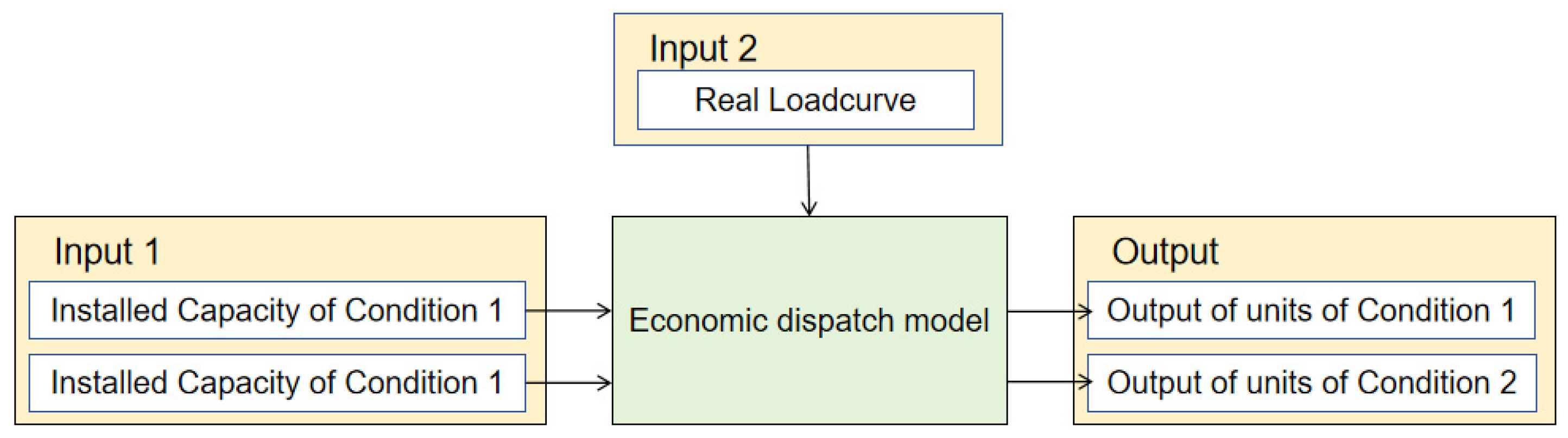

2.2.3. Economic Dispatch Model

- Objective Function:

- 2.

- Constraint:

2.2.4. Investment Deficit Measurement Model

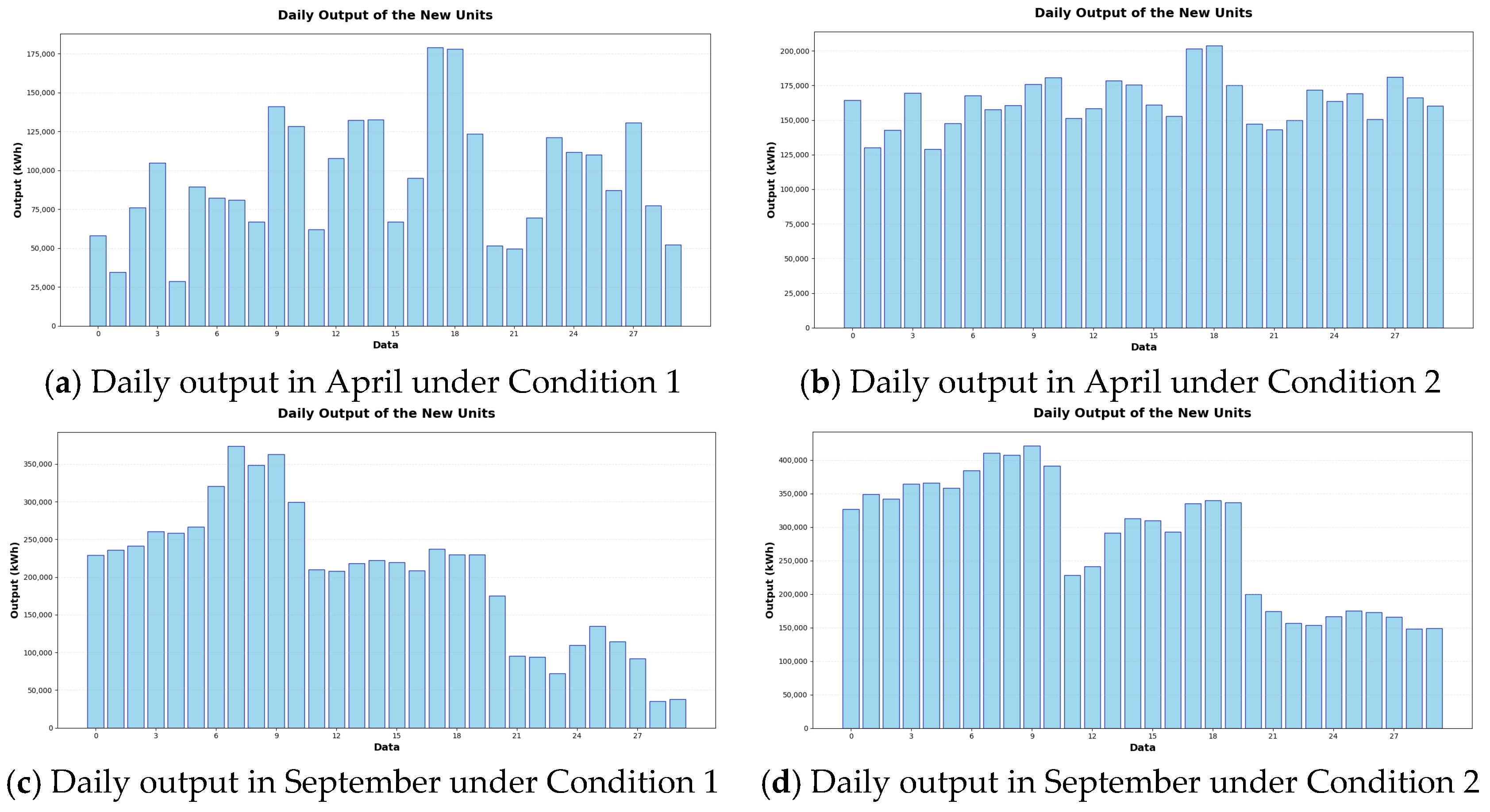

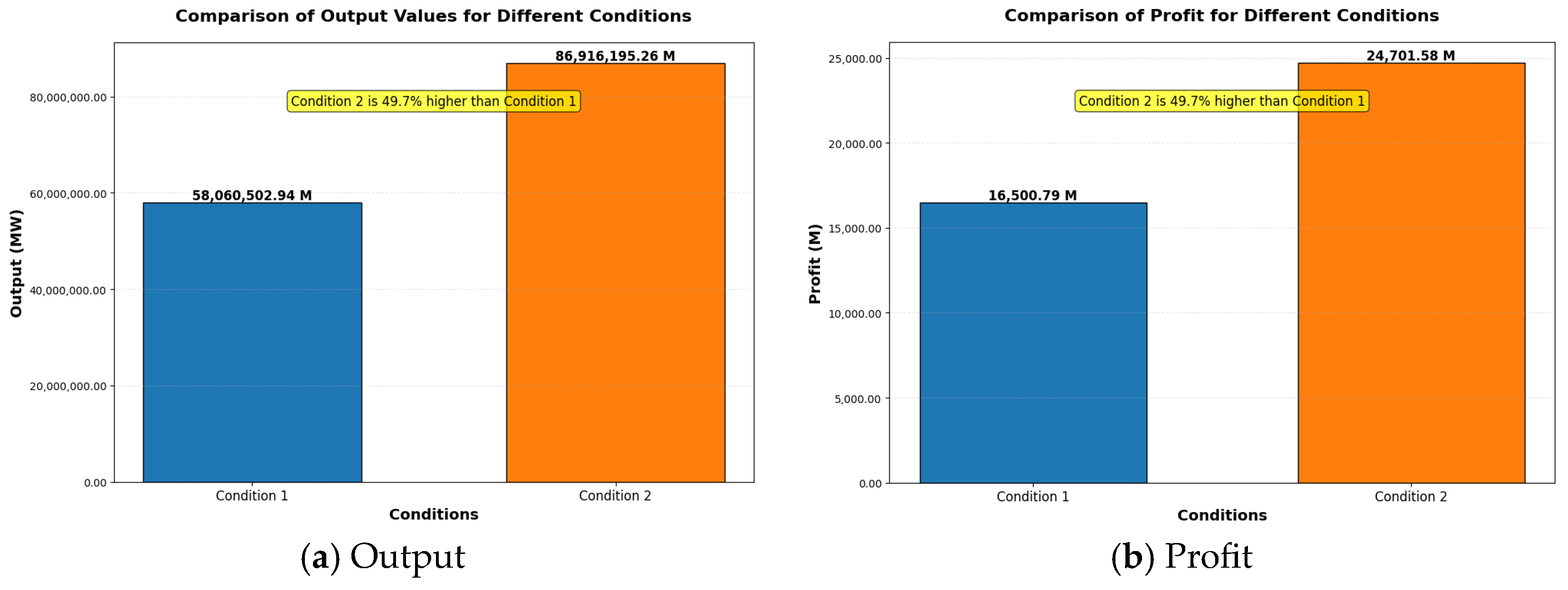

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GEP | Generation Expansion Planning |

| ED | Economic Dispatch |

| ID | Investment Deficit |

References

- Chen, S.Q.; Kharrazi, A.; Liang, S.; Fath, B.D.; Lenzen, M.; Yan, J.Y. Advanced approaches and applications of energy footprints toward the promotion of global sustainability. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Tran, T.P.T.; Ha, H.M.; Bui, T.D.; Lim, M.K. Sustainable industrial and operation engineering trends and challenges Toward Industry 4.0: A data driven analysis. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2021, 38, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.G.; Li, L.; Tseng, M.L.; Ahmed, A.; Shang, Z.X. A novel green design method using electrical products reliability assessment to improve resource utilization. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2021, 38, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L.; Li, Y.C.; He, Y.Z. Evaluation of power system equivalent inertia considering renewables virtual inertia. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Xiao, L.H.; Shang, H.L.; Xu, C.; Luo, Z.D.; Chen, J.J.; Ma, X.F. Design and application of energy internet digital twin system under the background of dual carbon. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2022, 37, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- EirGrid Plc. System and Renewable Data Summary Report [Data File]. 2021. Available online: https://www.eirgridgroup.com/site-files/library/EirGrid/System-and-Renewable-Data-Summary-Report.xlsx (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- EirGrid Plc.; SONI Ltd. All-Island Generation Capacity Statement [Online Report]. 2021. Available online: https://cms.eirgrid.ie/sites/default/files/publications/208281-All-Island-Generation-Capacity-Statement-LR13A.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Cao, J.; Gao, J.M. Coordination mechanism and simulation of household photovoltaic county development based on evolutionary game. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 669–684. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Fu, X.W.; Zhou, W.H. Two-staged generation-grid-load-energy storage interactive optimization operation strategy for promotion of distributed photovoltaic consumption. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 3786–3799. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.S.; Zhang, Z.H.; Guo, Y.H. Status and prospect of China’s wind power development in 2021. Water Power 2022, 48, 1–3+8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ho, M.S. Indirect cost of renewable energy: Insights from dispatching. Energy Econ. 2022, 105, 105778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xia, B.; Xu, L.; Zheng, Z. Analysis of renewable energy’s development in China and quantitative prediction of the power balancing gap. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Power and Energy Technology (ICPET), Beijing, China, 12–15 July 2024; pp. 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Koley, C.; Gope, S. Hybrid energy systems integrated power system imbalance cost calculation using moth swarm algorithm. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 316, pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, K.; Geng, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, K. Calculating wind variability costs with considering ramping costs of conventional power plants. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2019, 14, 2267–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfreda, A.; Parisio, L.; Pelagatti, M. A review of balancing costs in Italy before and after RES introduction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shao, C.; Yan, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Guo, C. Economical flexibility options for integrating fluctuating wind energy in power systems: The case of China. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Shi, W.; Shan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, H. Research on Renewables Operation Credible Capacity Evaluation and It’s Influence on Renewables Accommodation. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 23–26 March 2023; pp. 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

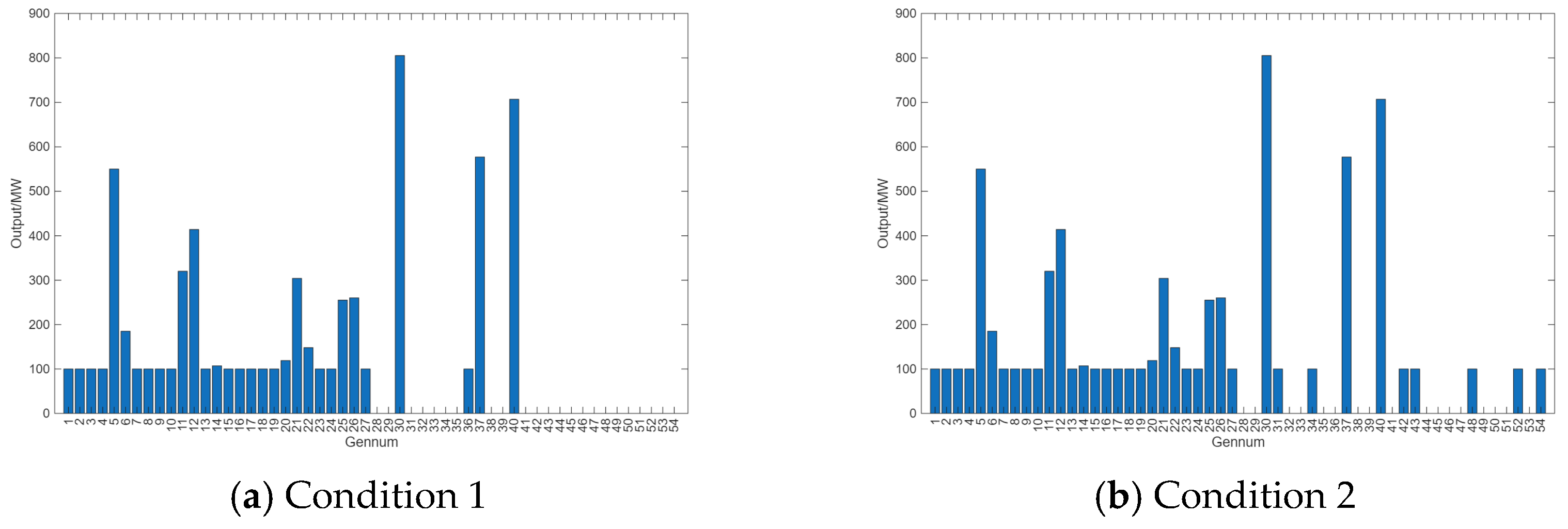

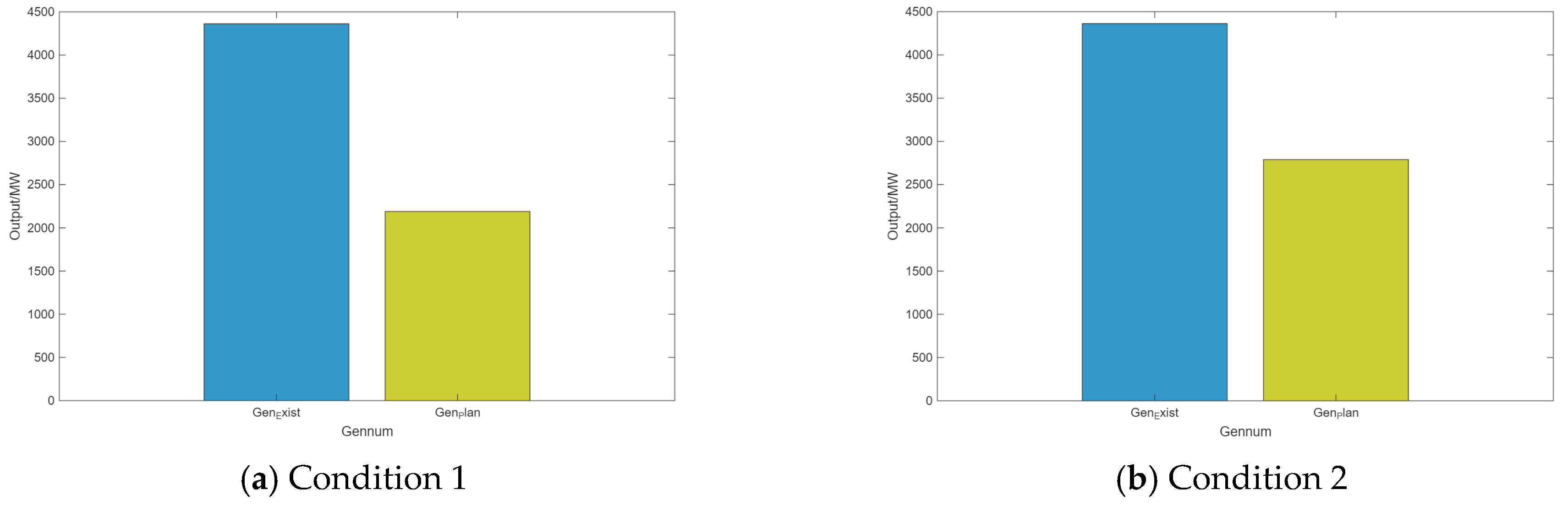

| Gen-num | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 |

| Capacity | 491 | 492 | 805.2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Plan1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plan2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gen-num | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 |

| Capacity | 577 | 100 | 104 | 707 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 352 |

| Plan1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Plan2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gen-num | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 |

| Capacity | 140 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 136 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Plan1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Plan2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, S.; Wang, K.; Sun, Z.; Xiang, M. Investment Deficit Measurement of Flexible Generation for Consuming Renewables. Processes 2026, 14, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030516

Zhang Z, Zhang M, Zhu S, Wang K, Sun Z, Xiang M. Investment Deficit Measurement of Flexible Generation for Consuming Renewables. Processes. 2026; 14(3):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030516

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhe, Meng Zhang, Siyu Zhu, Kun Wang, Zeyu Sun, and Mingxu Xiang. 2026. "Investment Deficit Measurement of Flexible Generation for Consuming Renewables" Processes 14, no. 3: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030516

APA StyleZhang, Z., Zhang, M., Zhu, S., Wang, K., Sun, Z., & Xiang, M. (2026). Investment Deficit Measurement of Flexible Generation for Consuming Renewables. Processes, 14(3), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14030516