Research on the Prediction of Pressure, Temperature, and Hydrate Inhibitor Addition Amount After Surface Mining Throttling

Abstract

1. Introduction

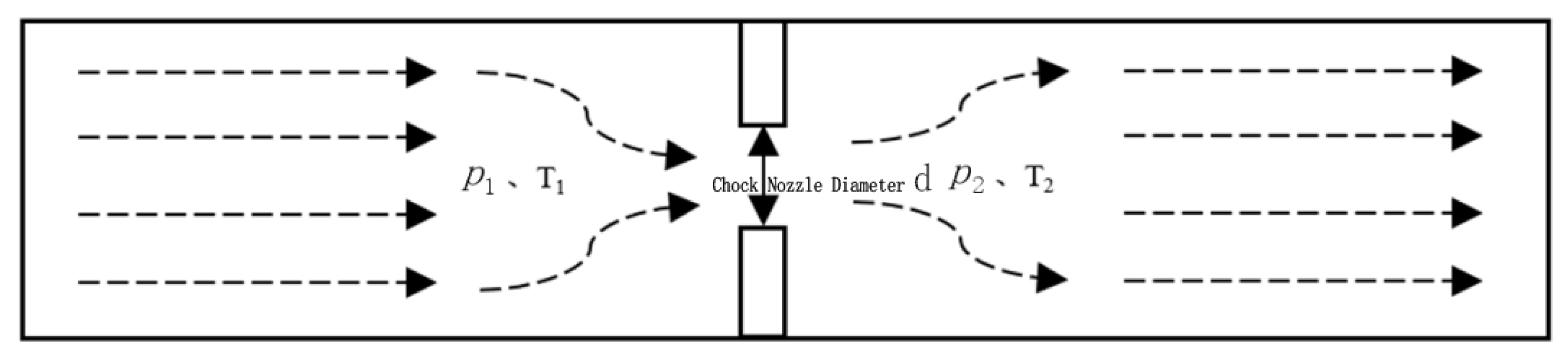

2. Horizontal Pipe Throttling Pressure and Temperature Prediction Model

2.1. Oil-Gas-Water Three-Phase Throttling Model

2.2. Throttling Pressure Drop Calculation

2.3. Throttle Temperature Drop Calculation

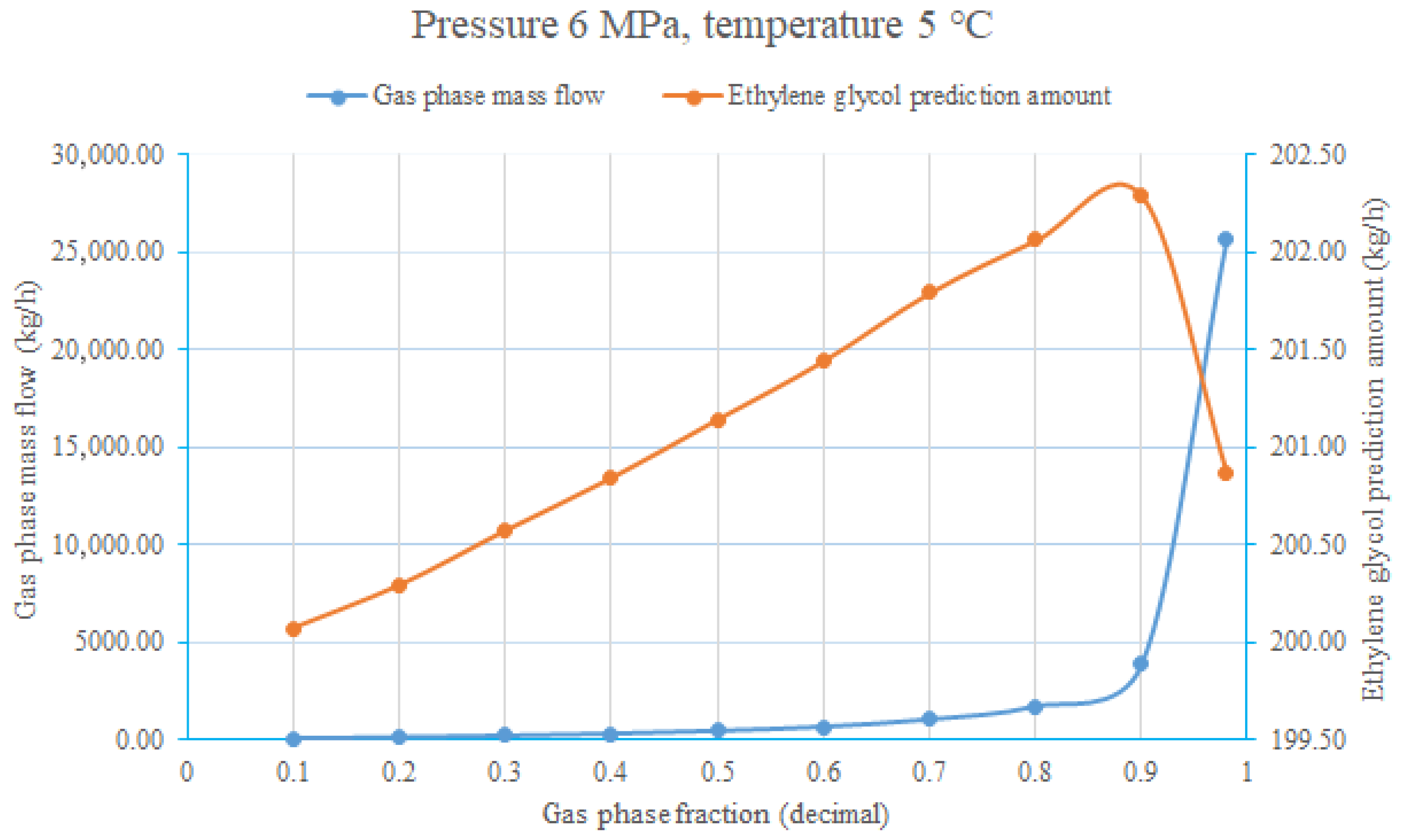

3. Predictive Model for Glycol Injection to Inhibit Freezing Blockage

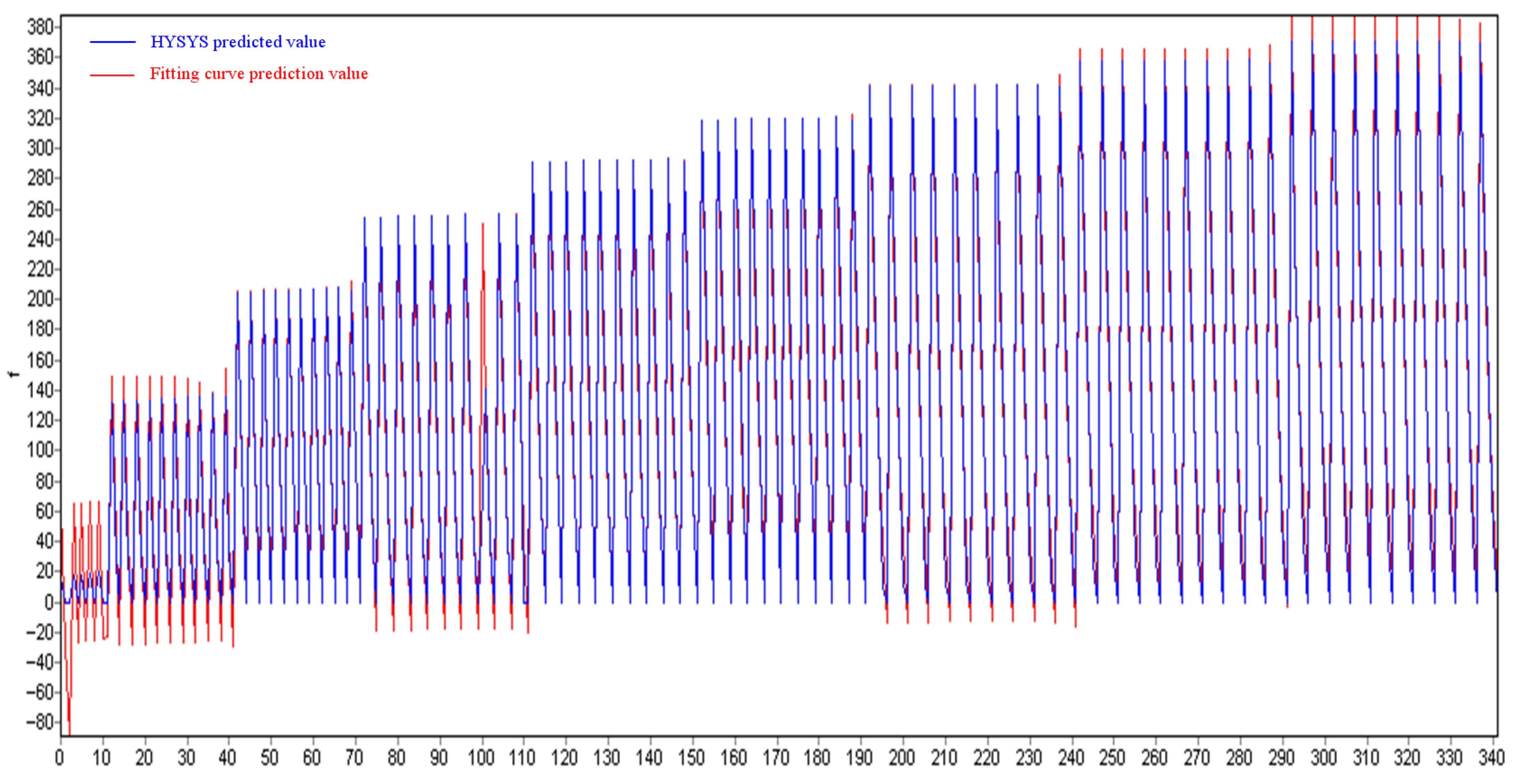

4. Real-Time Dynamic Adjustment and Optimization of the Calculation Process

5. Case Study Validation

5.1. Gas Well Production Environment Setup

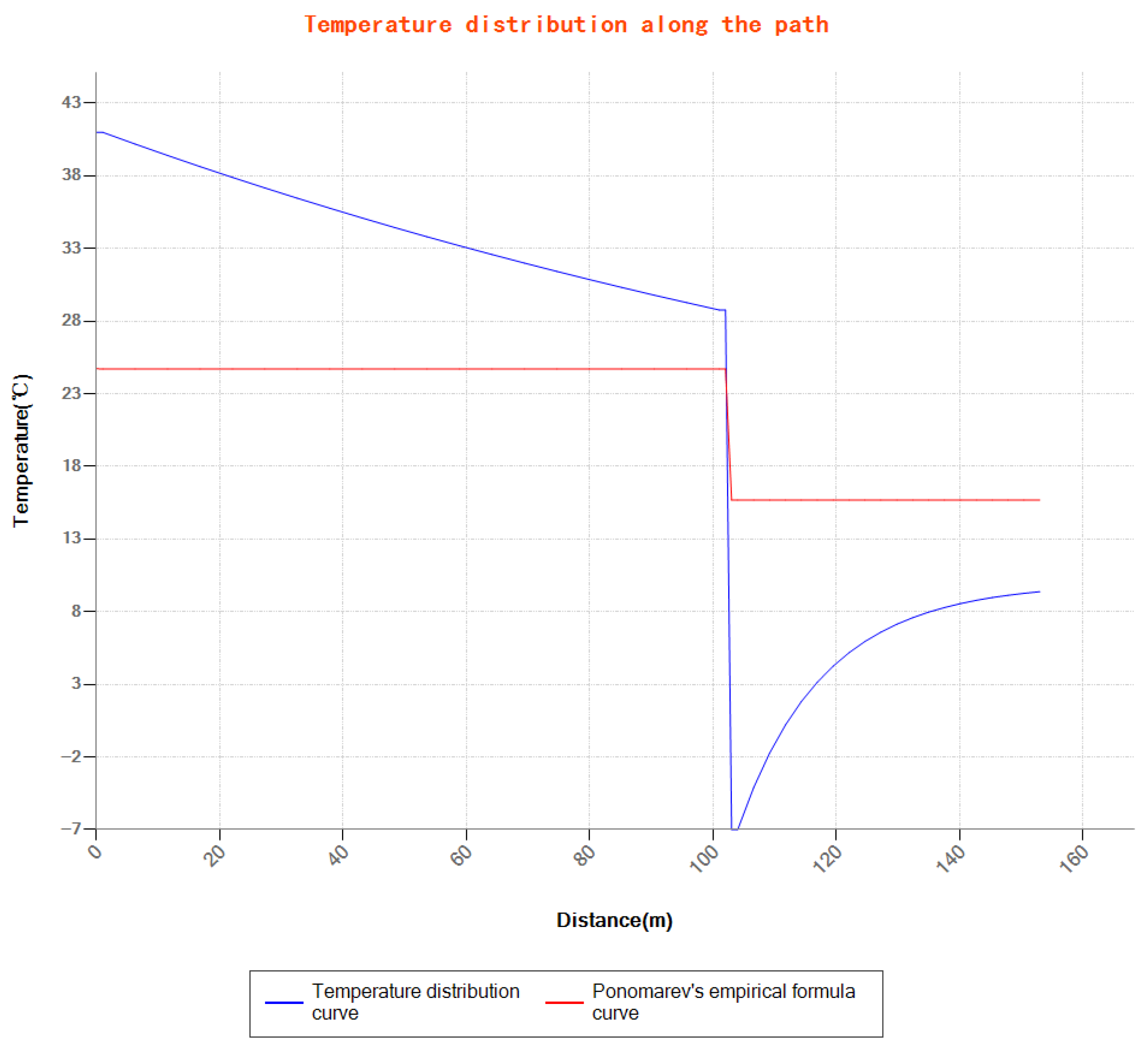

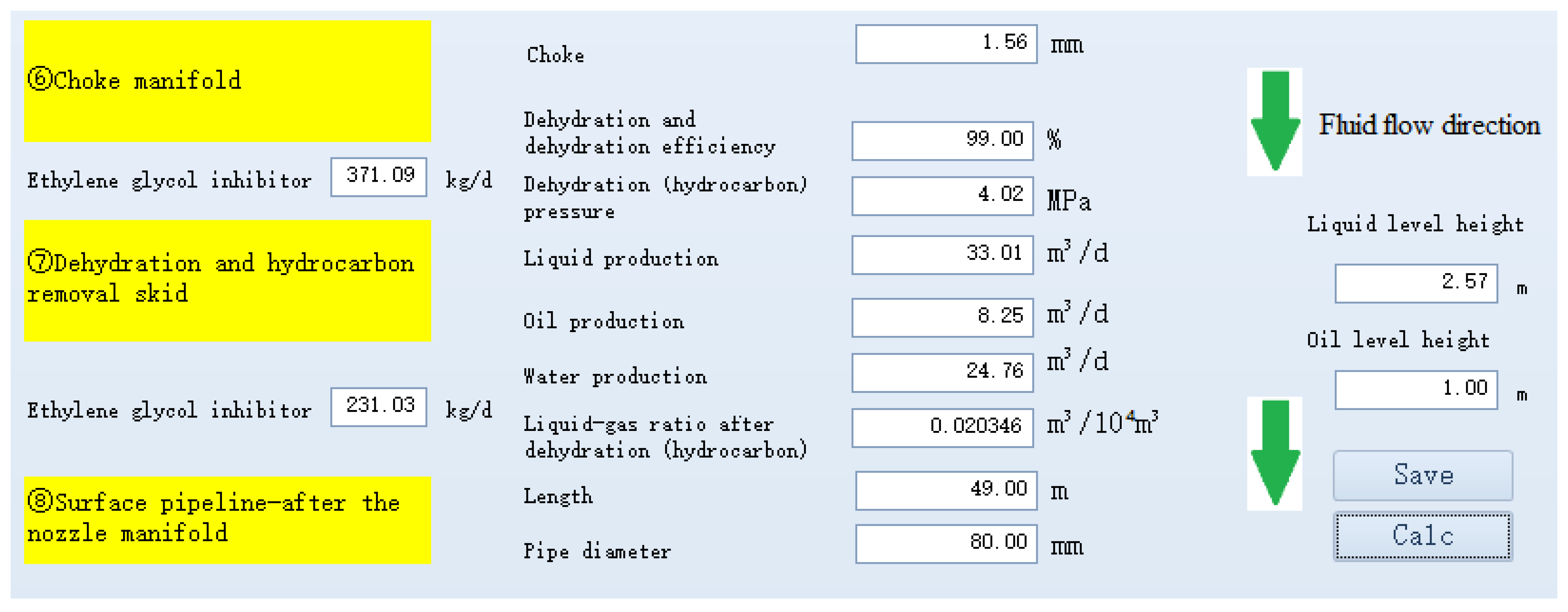

5.2. Prediction of Ground Pressure and Temperature Distribution Along the Path

5.3. Comparison with Measured Data

6. Conclusions

- Based on the law of energy conservation, the oil, gas, and water three-phase throttling model is derived, and the calculation method of multi-phase throttling pressure drop and temperature drop is proposed. The established three-phase throttling pressure and temperature prediction model theoretically reveals the dynamic changes in pressure and temperature during natural gas throttling with a certain liquid-to-gas ratio, providing a reliable basis for accurately predicting pressure and temperature parameters after throttling.

- Verified by field data from Well A, the model’s pressure and temperature prediction errors before and after throttling are both less than 6%, and the prediction error of the ethylene glycol injection amount required to suppress hydrates is less than 5%, indicating that the established model is highly reliable.

- The model can be deployed on edge computing devices to achieve real-time collection of production data, parameter prediction, and dynamic adjustment of ethylene glycol injection rate. In engineering applications, the ethylene glycol injection amount can be dynamically optimized based on the fluctuations of production parameters, such as gas production rate and liquid–gas ratio, during the trial production process. This not only avoids the risk of hydrate clogging caused by insufficient injection but also reduces the waste of resources caused by excessive injection. At the same time, providing data support for throttling device parameter optimization and pipeline safe operation has important practical significance for improving the safety, efficiency, and economy of natural gas trial production projects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duns, H.; Ros, N.C.J. Vertical flow of gas and liquid mixtures in wells. In Proceedings of the 6th World Petroleum Congress, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 19–26 June 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, N.C.J. An Analysis of Critical Simultaneous Gas/Liquid Flow Through a Restriction and Its Application to Flowmetering. Appl. Sci. Res. 1960, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poettmann, F.H.; Beck, R.L. New Charts Developed to Predict Gas-Liquid Flow through Chokes. World Oil 1963, 184, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, W.E. Flowing and gas-lift well Performance. API Drill. Prod. Pract. 1954, 13, 126–157. [Google Scholar]

- Secen, J.A. Surface Choke Measurement Equation Improved by Field Testing and Analysis. Oil Gas J. 1976, 30, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Baxendeil, P.B. Bean Performance-Lake Wells; Shell Internal Report; Shell Oil Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Achong, I.B. Revised Bean and Performance Formula for Lake Maracaibo Wells; Shell Internal Report; Shell Oil Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Pilehvad, A.A. Experimental Study of Subcritical Two-Phase Flow Through Wellhead Chokes; Fluid Flow Projects Report; University of Tulsa: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, M.E.; Dokla, M.E. Gas Condensate Flow through Chokes. In Proceedings of the European Petroleum Conference, The Hague, The Netherlands, 21–24 October 1990. [Google Scholar]

- AI-Attar, H.H.; Abdui-Majeed, G. Revised Bean Performance Equation for East Baghdad Oil Wells. SPE Prod. Eng. 1988, 3, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omana, R.; Houssiere, C.; Brown, K.; Brill, J.P.; Thompson, R.E. Multiphase flow through chokes. In Proceedings of the Fall Meeting of the Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME, Denver, CO, USA, 28 September–1 October 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunati, E. Two-phase Flow through Wellhead Chokes. In Proceedings of the SPE European Spring Meeting, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 16–18 May 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva, R. Two Phase Flow through Chokes. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–8 October 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Valvatne, P.H.; Serve, J.; Durlofsky, L.J.; Aziz, K. Efficient modeling of nonconventional wells with downhole inflow control devices. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2003, 39, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xu, H.L.; Shi, T.H.; Zou, A.Q.; Mu, Z.H.; Guo, J.H. Downhole multistage choke technology to reduce sustained casing pressure in a HPHT gas well. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 26, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Li, Y.C.; Du, Z.M. Mathematical model for predicting gas-liquid two-phase throttling in high gas-liquid ratio gas wells. Nat. Gas Technol. 2005, 25, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, G.; Li, C.; Liu, J. Study on design method of downhole throttling technology for high-pressure gas wells. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2007, 30, 57–59+62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.X.; Zhang, P.; Zheng, R.; Ma, L.; Yang, C. A new model for gas-liquid two-phase choke flow and its application. Lithol. Reserv. 2021, 33, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, P.; Luo, R. Application of downhole throttling and cooling technology in the eastern South China Sea gas fields. Petrochem. Technol. 2022, 29, 15–18+119. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.Y. Optimization of Downhole Throttling Process Parameters for Gas Wells with High Water Content. Master’s Thesis, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China, 2023. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/D03137350 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Hu, L.; Liu, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J. Study on the glycol injection system for low-temperature separation process. Nat. Gas Pet. 2006, 24, 19–21+73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Tang, T.; Liu, X.; Zhu, C. Optimization analysis of glycol injection amount at the first gas processing plant of Kela-2 gas field. Pet. Nat. Gas Chem. Ind. 2008, 37, 15–17+4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jing, X.; Cao, Y. Calculating natural gas hydrate inhibitor injection amount through HYSYS. Nat. Gas Pet. 2013, 31, 49–51+9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. Prediction of Natural Gas Pipeline Hydrates and Calculation of Inhibitor Dosage. Nat. Gas Technol. Econ. 2017, 11, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.L.; Liao, R. Prediction Model of Natural Gas Hydrate Based on ISCA-BP Algorithm. Chem. Eng. China 2022, 50, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, J.; Lyu, Y.; Lin, X.; Yong, S.; Luo, W.; Chen, W. Research on underground throttle calculation model based on actual production of rich water gas reservoir. J. Yangtze Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 22, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, T.K. Critical and Subcritical Flow of Multiphase Mixtures Through Chokes. SPE Drill. Complet. 1993, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wellhead Pressure (MPa) | Liquid Production (m3/d) | Gas Production (m3/d) |

|---|---|---|

| 12.5 | 44.4 | 164,000 |

| Pressure Before Throttling (MPa) | Temperature Before Throttling (°C) | Pressure After Throttling (MPa) | Temperature After Throttling (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | 12.50 | 28.31 | 4.19 | −7.41 |

| Simulation Calculation | 12.37 | 28.79 | 4.02 | −6.97 |

| Absolute Relative Error (%) | −4.11 | −5.98 |

| Ethylene Glycol Addition (kg/d) | |

|---|---|

| Actual | 378 |

| Simulation Calculation | 370.93 |

| Absolute Relative Error (%) | 1.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, J.; Fu, G.; Luo, W.; Wang, J. Research on the Prediction of Pressure, Temperature, and Hydrate Inhibitor Addition Amount After Surface Mining Throttling. Processes 2026, 14, 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020376

Peng D, Wu Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Wei J, Fu G, Luo W, Wang J. Research on the Prediction of Pressure, Temperature, and Hydrate Inhibitor Addition Amount After Surface Mining Throttling. Processes. 2026; 14(2):376. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020376

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Dake, Yuxin Wu, Yiyun Wang, Hong Wang, Junji Wei, Guojing Fu, Wei Luo, and Jihan Wang. 2026. "Research on the Prediction of Pressure, Temperature, and Hydrate Inhibitor Addition Amount After Surface Mining Throttling" Processes 14, no. 2: 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020376

APA StylePeng, D., Wu, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Wei, J., Fu, G., Luo, W., & Wang, J. (2026). Research on the Prediction of Pressure, Temperature, and Hydrate Inhibitor Addition Amount After Surface Mining Throttling. Processes, 14(2), 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14020376