1. Introduction

Ore drawing in the caving method induces the collapse of the ore body and its overlying rock under the action of gravity, followed by passive and non-visual ore extraction through drawpoint at the base [

1,

2]. As an efficient, low-cost, safe, and geologically adaptable large-scale underground mining method, more than 85% of iron ores and approximately 40% of non-ferrous metal ores in Chinese underground mines are extracted using this approach, while globally, about 25% of mines employ this method [

3,

4]. However, during the caving-based ore-drawing process, the inadvertent inclusion of overlying strata or surrounding rock is inevitable, resulting in ore dilution, and ore retention within the ore body may cause permanent loss due to unrecovered materials [

5,

6]. Moreover, under actual mining conditions, some ore bodies contain interburden, which mainly consists of low-grade ore particles or particles of other mineral types. These interburden particles are released together with ore particles during drawdown. On one hand, this leads to a reduction in ore grade, exacerbating ore dilution; on the other hand, it significantly affects the flow characteristics and interface morphology of ore particles, thereby negatively impacting ore-drawing planning and production efficiency. Therefore, accurately understanding the migration trajectories of this special interburden particle assembly during ore drawing, as well as subsequently controlling its migration through adjustments of ore-drawing parameters, is of critical importance for effectively minimizing dilution, enhancing the ore grade, and improving resource recovery.

In situ field experiments and small-scale physical model tests are important approaches for investigating the ore-drawing mechanisms in the caving method [

7,

8,

9]. However, these approaches are objectively limited by complex site conditions, high experimental costs, and difficulties in marker preparation and recovery. With the rapid development of computational simulation technologies, researchers worldwide have increasingly employed numerical simulation methods to study complex particulate flow phenomena under various scenarios. Among these, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) directly simulates particles with high computational accuracy and has seen growing application in mining engineering, particularly in gravity-flow extraction methods such as Block Caving, where it is used to model the flow behavior of ore and waste rock to optimize mining parameters and improve recovery. For instance, R.-X. Zhang et al. [

10] employed DEM to investigate the influence of post-obstacle accumulation height on the impact mechanisms of dry granular flows, revealing the complexity of particle motion. Yang et al. [

11] used PFC3D to explore particle-scale characteristics in the extraction zone during block caving, particularly the effects of particle size distribution on flow behavior. Jin et al. [

3] examined the shape of the extracted ore mass in single-drawpoint experiments, influencing factors, and the relationships between multiple factors and ore loss in multi-drawpoint scenarios. These studies demonstrate the strong capability of DEM in simulating complex particle flows, revealing both inter-particle interactions and macroscopic flow characteristics. Nevertheless, most existing studies focus on ore flow patterns under conditions without interburden, while research on the motion behaviors of special particles under interburden conditions remains limited. Furthermore, numerical simulations under varying operational conditions and different interburden geometries require repeated modeling and extensive computations, resulting in significant time consumption and limited scalability.

Moreover, researchers have developed various mathematical models, such as the ellipsoidal ore-drawing theory, stochastic medium ore-drawing theory, and Bergmark–Roos equation-based ore-drawing theory, to describe and analyze the shapes of the isolate extraction zone (IEZ), isolate movement zone (IMZ), and residual ore masses. Experimental observations, however, indicate that the extracted ore mass does not form a true ellipsoid [

12,

13]. Although approximating it as an ellipsoid can still guide extraction design, this simplification tends to increase ore loss and dilution. Chen [

14] noted substantial discrepancies between the extracted ore shapes predicted by the mobility probability density equation and physical experiments, and proposed corresponding improvements. The Bergmark–Roos equation-based ore-drawing theory consolidates various factors affecting the extracted mass shape into the internal friction angle of the granular material [

4,

15,

16], upon which several enhancements have been developed. Nevertheless, due to the differing physical and mechanical properties of interburden and ore, as well as the variability in interburden size and morphology, these widely applied theoretical models still face challenges in adaptability and prediction accuracy when estimating residual ore shapes. Considering the engineering context and the reliability of predictive models is therefore of both theoretical and practical significance.

In recent years, deep learning methods have demonstrated outstanding performance in the prediction of complex systems. For instance, Jolfaei and Lakirouhani [

17] successfully employed neural networks to conduct parameter sensitivity analysis and predict failure morphology in borehole breakout studies, highlighting the particular suitability of such approaches for addressing strongly nonlinear and spatiotemporally correlated particle migration problems. Lu et al. [

18] proposed a machine learning-accelerated DEM approach, embedding deep neural networks within particle flow computations to significantly reduce simulation workload. Liao et al. [

19] combined DEM and deep learning techniques to predict particle flow behavior in wedge-shaped hoppers from image data, achieving high-precision and rapid predictions of flow patterns. Hadi et al. [

20] developed a transfer learning-based adaptive surrogate model for DEM simulations of multi-component particle segregation processes, substantially improving generalization and computational efficiency. These studies indicate that integrating deep learning architectures into particle migration modeling not only markedly accelerates simulation speed but also maintains high predictive accuracy while capturing complex physical mechanisms, providing a novel technical route and theoretical foundation for predicting multilayer interface migration outcomes during ore drawing.

To address the challenge of predicting boundary particle migration under interburden conditions during ore drawing with the caving method, this study first designs a dataset construction strategy. The angle of repose parameters is accurately calibrated through numerical simulation experiments, resulting in a single-drawpoint numerical simulation dataset encompassing both post-defined and pre-defined interburden models. Building upon this dataset, an improved Transformer model is proposed. The model incorporates a multi-layer feature fusion embedding module at the input stage, strengthens spatiotemporal attention mechanisms in the backbone, and optimizes the decoding structure at the output stage, thereby enabling simultaneous capture of complex spatiotemporal dependencies and local dynamic variations in particle motion. Based on this framework, the proposed model is pre-trained, transfer-trained, and validated on the dataset, and systematically evaluated in terms of coordinate prediction, trajectory reconstruction, and prediction of key nodes related to ore grade variations during extraction.

2. Database

This study is based on the Yanjian Mountain iron mine in Anshan, Liaoning Province, China, which was initially operated as an open-pit mine and has now been fully converted to underground mining. The western section of the ore body is designed to be extracted using the ore drawing in the caving method. The ore body contains iron carbonate interburden, and the granular flow state within the mining zone is unknown; ignoring the proper release of interburden during extraction may lead to ore dilution. Although in situ experiments most accurately reflect the actual ore-drawing process, they are time-consuming, costly, and technically challenging, with limited reproducibility and systematic regularity. Traditional physical experiments also face inherent limitations in material preparation, environmental control, and parameter measurement, including long operational cycles, high costs, and difficulties in precisely regulating boundary conditions. For studying multilayer interface migration under interburden conditions during ore drawing, numerical simulation techniques offer significant technical advantages.

Accordingly, this study proposes a dataset construction strategy. First, the angle of the repose calibration method is used to determine all necessary parameters for numerical simulation experiments. Subsequently, small-scale single-drawpoint numerical simulations are conducted, establishing an ore-drawing dataset incorporating interburden models (both post-defined and pre-defined) suitable for subsequent deep learning experiments.

2.1. Numerical Simulation for Calibration of the Angle of Repose

In the DEM-based particle flow simulation software, micro-mechanical parameters are assigned to rigid particles and their contacts, and the Newtonian equations of motion are solved for each particle to determine the model’s macroscopic mechanical properties. In numerical simulations of ore drawing in the caving method, PFC establishes the relationship between microscopic contact parameters (such as stiffness and friction coefficient) and macroscopic mechanical behavior by dynamically solving the motion equations of rigid particles. Since no explicit mathematical relationship exists between microscopic parameters and macroscopic properties, a trial-and-error approach is required to adjust the parameters until the simulation results match physical experiments.

The natural angle of repose represents the maximum angle that a bulk material can form between its piled slope and the horizontal plane under specific conditions and serves as a comprehensive indicator of the material’s mechanical properties. When the simulated angle of repose coincides with that obtained from physical experiments, the macroscopic characteristics reflected by the micro-level particle and contact parameters are considered consistent with those of real ore and rock bulk material [

21,

22]. In granular mechanics, the natural angle of repose is closely related to the internal friction angle of the material. For cohesionless granular materials, the repose angle generally approximates or is slightly smaller than the internal friction angle, as it reflects both interparticle friction and geometric packing effects. Therefore, by calibrating the simulation micro-parameters to match the experimentally measured angle of repose, the effective macroscopic internal friction behavior of the particles is indirectly captured. This approach provides a practical and reliable method to ensure that the simulated particle flow and slope stability are consistent with real ore and interburden materials, without requiring an explicit mathematical relationship between microscopic friction coefficients and macroscopic internal friction.

The natural angle of repose was determined via the collapse method using Particle Flow Code (PFC 2D) software (version 6.0; Itasca Consulting Group, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). A schematic of the numerical setup is illustrated in

Figure 1. A certain quantity of particles is generated above a fixed-funnel, gradually filling it under the action of gravity. The funnel gate is then opened, allowing the particles to flow out and accumulate beneath the funnel, forming a pile. The angle of repose of the pile is measured and compared with that obtained from physical experiments. Based on the deviation between the simulated and experimental angles, the microscopic parameters are iteratively adjusted. This trial-and-error procedure is repeated, with parameters being systematically refined in each iteration, until the simulated angle of repose converges to the experimental value within an acceptable tolerance, indicating that the macroscopic mechanical behavior of the particles is realistically captured. The parameters of ore particles, interburden particles, and waste rock particles are all calibrated using this method. After extensive trials and iterative adjustments, the final calibrated parameters are listed in

Table 1. This procedure ensures that the DEM model reliably reproduces the bulk mechanical behavior and flow characteristics of the materials under study.

Parameters are adjusted, and the procedure is repeated until the simulation results match the experimental observations. The parameters of ore particles, interburden particles, and waste rock particles are all calibrated using this method. After extensive trials, the final calibrated parameters are listed in

Table 1. The micro-mechanical parameters are defined as follows: kn and ks represent the normal stiffness and shear (tangential) stiffness of particle contacts, respectively, with units of N/m. Density (kg/m

3) represents the mass density of individual particles. fric represents the contact friction coefficient between particles (dimensionless), controlling the resistance to sliding at particle contacts. Damp represents the local damping coefficient (dimensionless), which governs energy dissipation during particle collisions. rr_fric represents the rolling resistance coefficient (dimensionless), representing the resistance to particle rotation at contacts.

2.2. Construction of the Ore-Drawing Dataset with Interburden

A single-hole ore-drawing numerical simulation was conducted using a 1:100 scale model. The model dimensions were 800 mm × 1000 mm (length × height), with a 40 mm wide ore-drawing opening located at the center of the base. Approximately 8000 particles were included in the simulation. To prevent excessive particles overlap that could induce unrealistically high velocities, particles were initially distributed uniformly at random. A gravitational acceleration of 9.8 m/s2 was applied, allowing the particles to settle under gravity and reach an initial equilibrium corresponding to natural piling.

2.2.1. Post-Defined and Pre-Defined Interburden Models

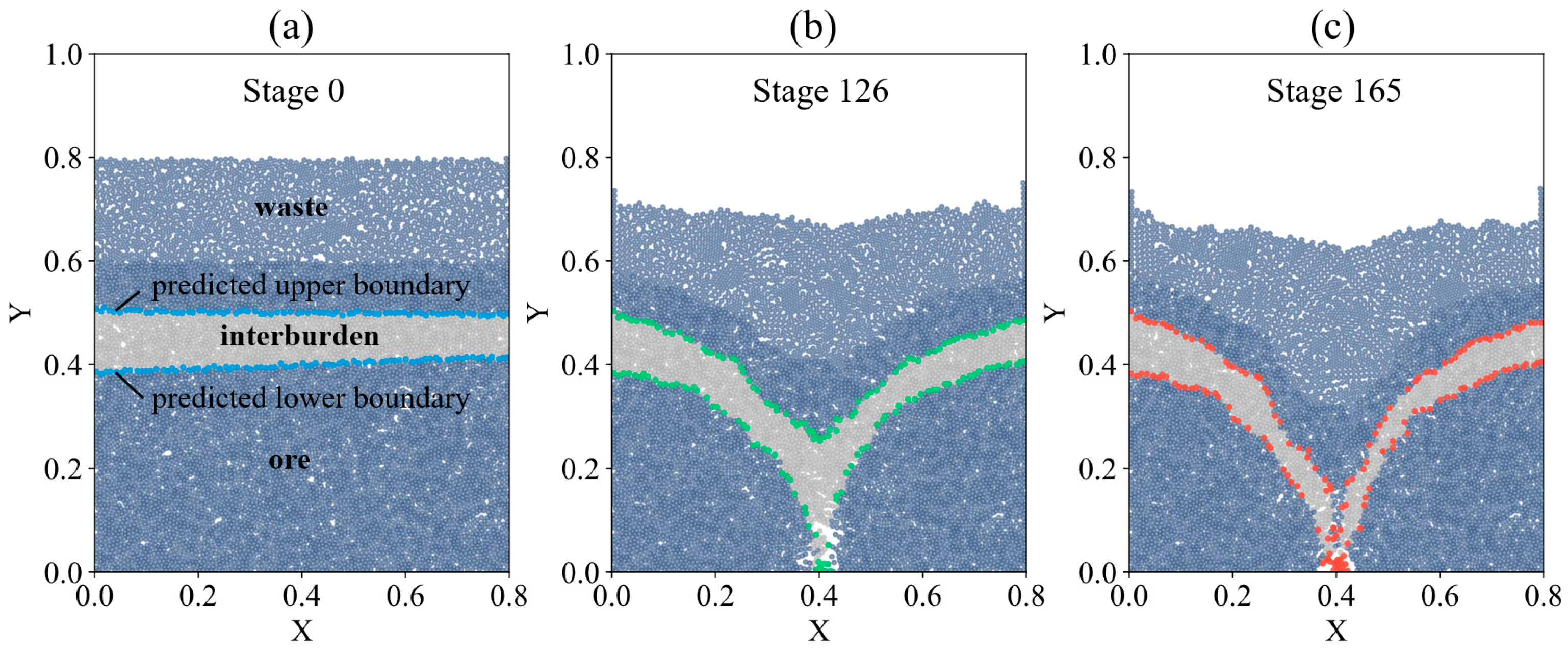

As shown in

Figure 2, the generation of the pre-defined interburden model involves the following steps: (a) First, ore particles are generated up to a height of 0.8 m. (b) After reaching equilibrium, particles above the lower boundary are removed, and a wall is created at the lower boundary position. (c) Particles with specific properties are generated in the height range of 0.6–1.0 m. After equilibration, particles above the upper boundary are removed, and a wall is created at the upper boundary. (d) Waste rock particles are generated in the height range of 0.6–1.0 m. After equilibration, particle above 0.8 m are removed, and the walls at both the upper and lower boundaries are removed. After a subsequent equilibration, the initial pre-defined model is obtained. The ore-drawing simulation process using the pre-defined model is shown in

Figure 3.

The numerical model was established under a two-dimensional plane strain assumption. Rigid walls were applied at the left, right, and bottom boundaries to restrict lateral and basal particle movement, while the top boundary was left free to allow gravity-driven deposition and flow. Gravity was the only external load applied in the simulations, with a gravitational acceleration of 9.8 m/s2. Different geological layers were represented by assigning distinct particle properties (e.g., density, contact stiffness, and friction coefficient) rather than by defining explicit geometric interfaces. Interactions between different layers were governed by particle–particle contacts, and the mechanical behavior at layer boundaries emerged naturally from contacts between particles with different properties. Prior to ore drawing, particles were allowed to settle under gravity until a quasi-static equilibrium state was reached, after which the ore-drawing process was initiated.

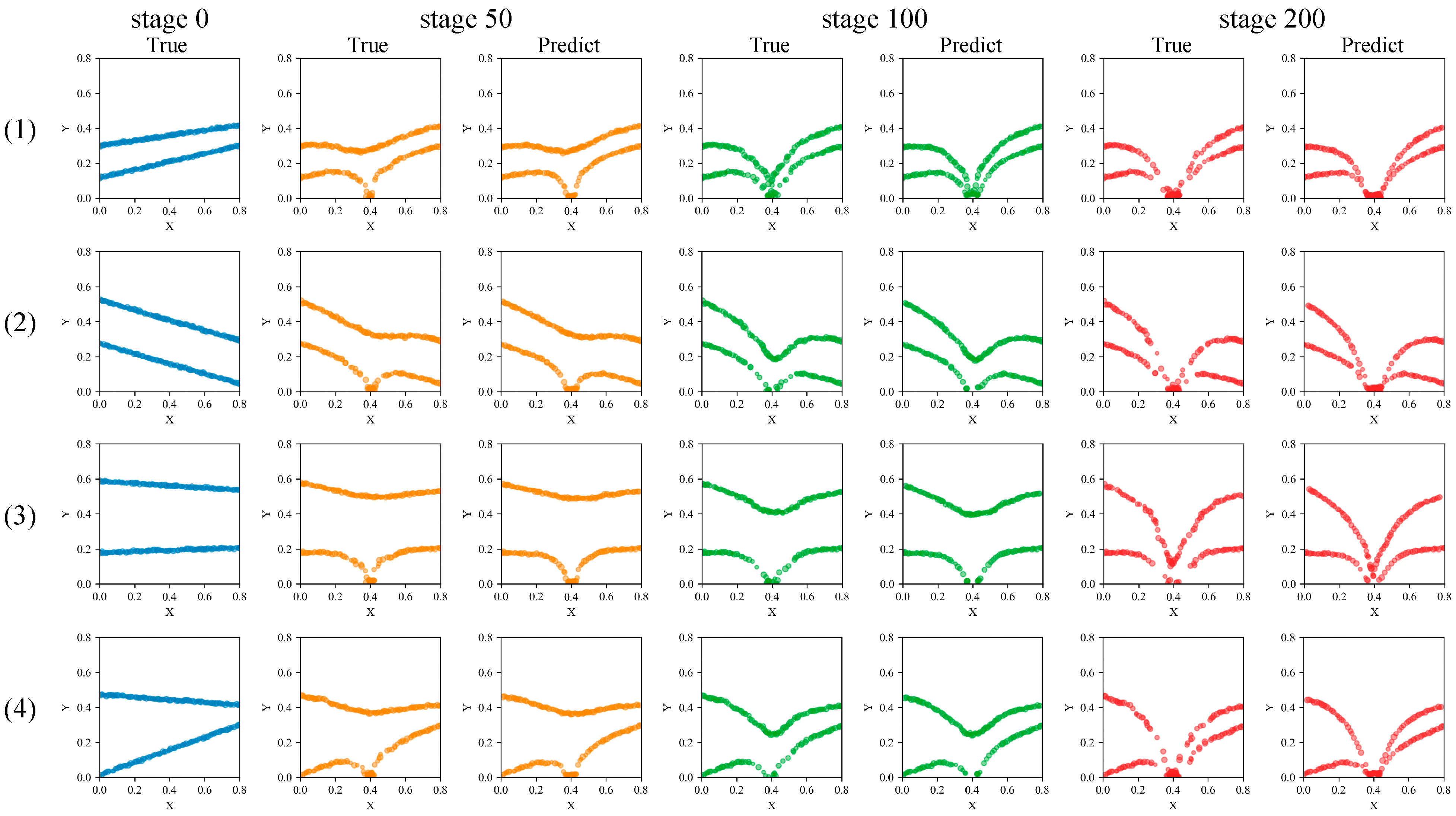

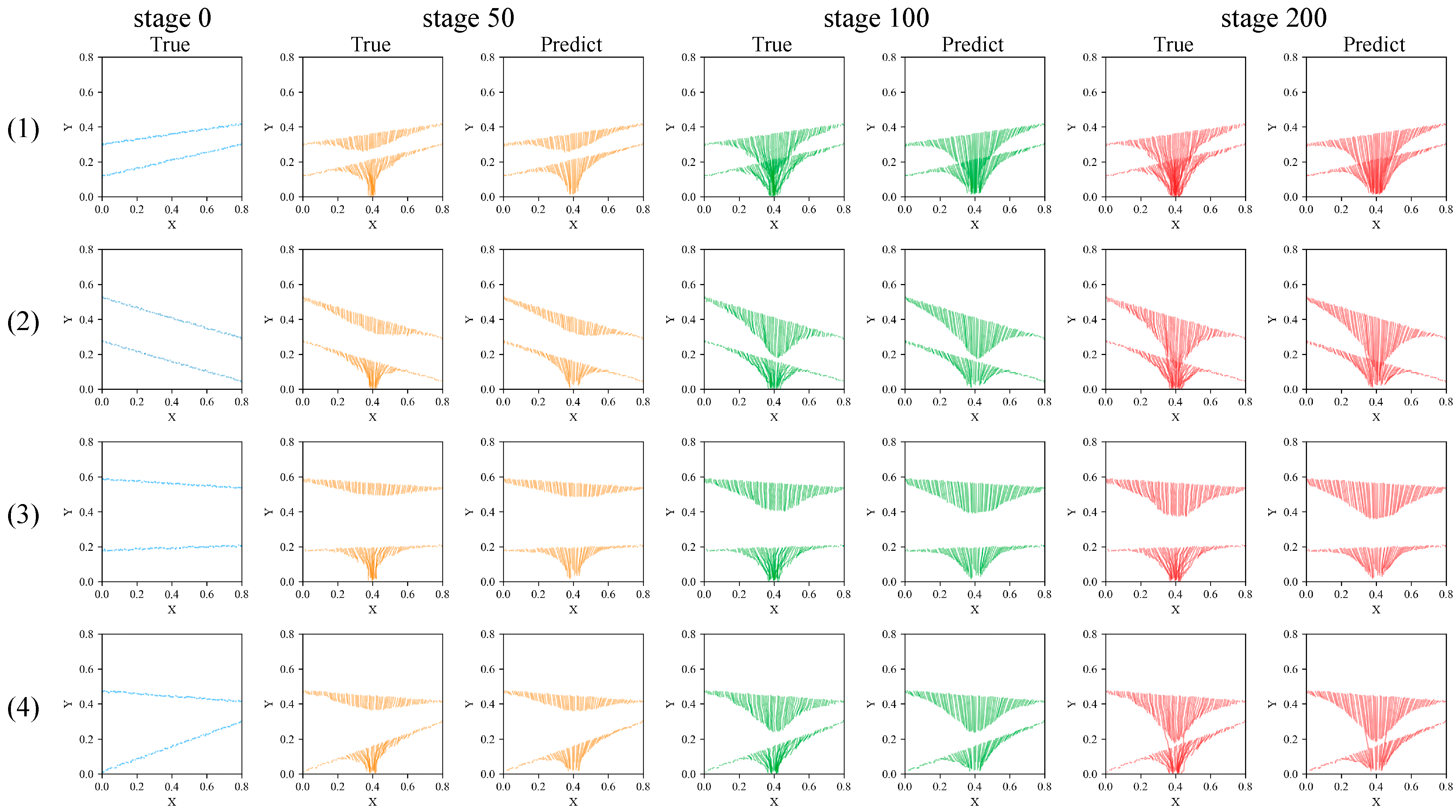

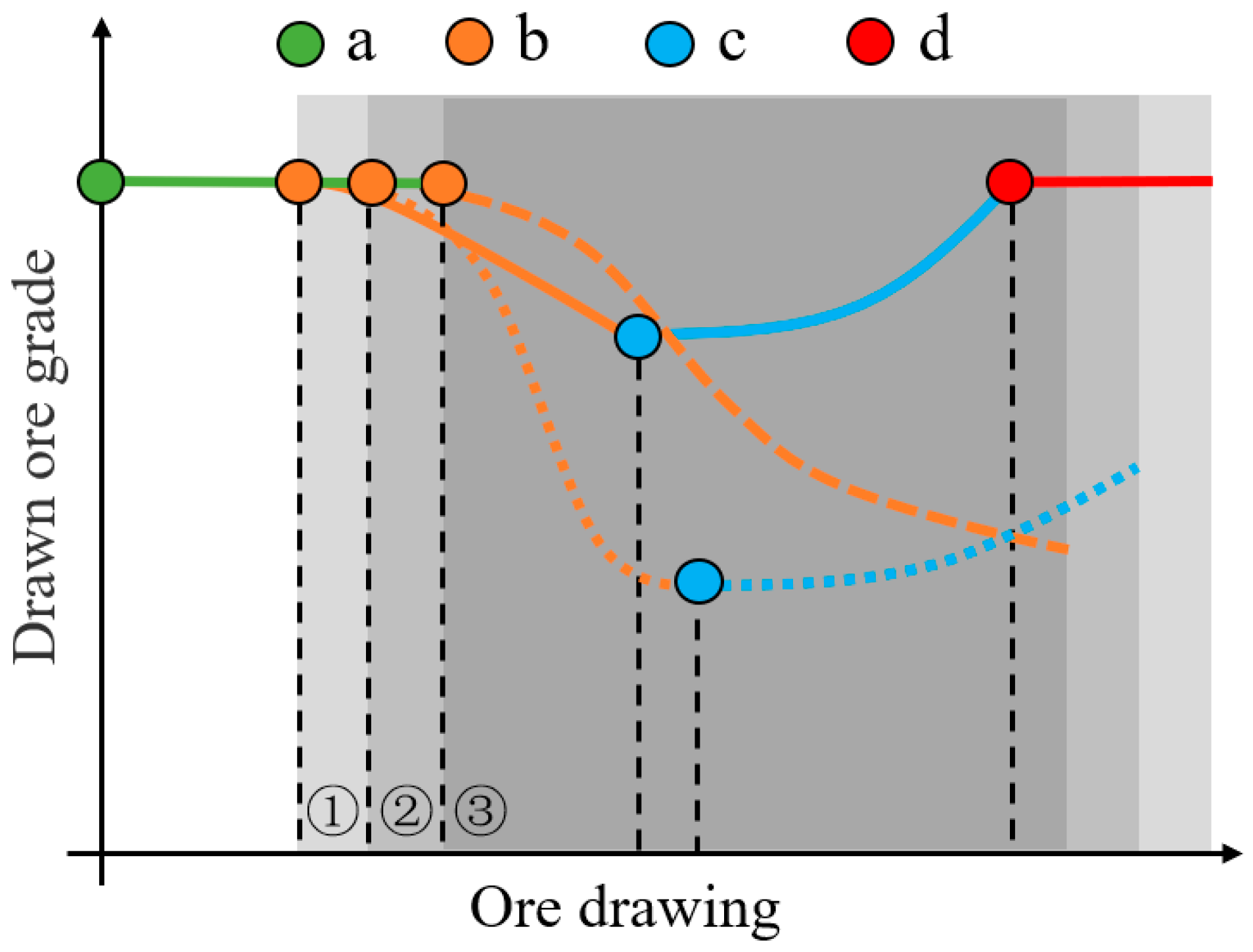

The ore-drawing process is halted when the waste rock particles, representing the covering layer (above 0.6 m), are first released. The simulation process for ore drawing using the pre-defined model is illustrated in

Figure 3. Since the position and morphology of the interburden are neither fixed nor uniform, its shape evolution before and after ore drawing still follows a traceable pattern. The interburden, defined as a collection of specific particles, generally spans the ore-drawing zone of a single-hole model. This collection can be represented as the region bounded by upper and lower boundaries. Therefore, by determining the morphological changes in these two boundary lines before and after ore drawing, the evolution of the interburden can be obtained.

For the numerical simulations of the pre-defined interburden, it is sufficient to record the states of particles along the upper and lower boundaries of the interburden at all stages to obtain the corresponding dataset. However, since the position and morphology of the interburden are neither fixed nor uniform, each generation of the specific particle collection model requires predefining the upper and lower boundaries, followed by stepwise particle generation. Moreover, such simulations can only represent a single multilayer interface scenario. To obtain a large dataset under diverse conditions, extensive simulations would be required, resulting in significant computational cost.

Considering the complexity and computational time of model generation and calculation, using pre-defined interburden models is not conducive to acquiring sufficient data for training deep learning models. Therefore, we adopt an alternative approach: a particle collection model without interburden is first generated, and the states of all particles are recorded at all stages. Subsequently, by randomly setting the upper and lower boundaries, large amounts of post-defined interburden data with varying interface morphologies can be obtained. Following the concept of transfer learning [

23,

24,

25], the easily accessible and large-scale post-defined interburden dataset is first used for pretraining to acquire reasonably optimized weights. These weights are then transferred through fine-tuning using the smaller, but more production-representative pre-defined interburden dataset to achieve higher accuracy.

The generation of the post-defined model involves the following steps: first, ore particles are generated up to a height of 0.8 m. After equilibration, particles above 0.6 m are removed. Next, covering layer waste rock particles are generated in the height range of 0.6–1.0 m. After another equilibration, particles above 1.0 m are removed. The stopping condition for ore drawing is the same as that of the pre-defined modesl. The ore-drawing simulation process of the post-defined model is illustrated in

Figure 4.

2.2.2. Building Datasets

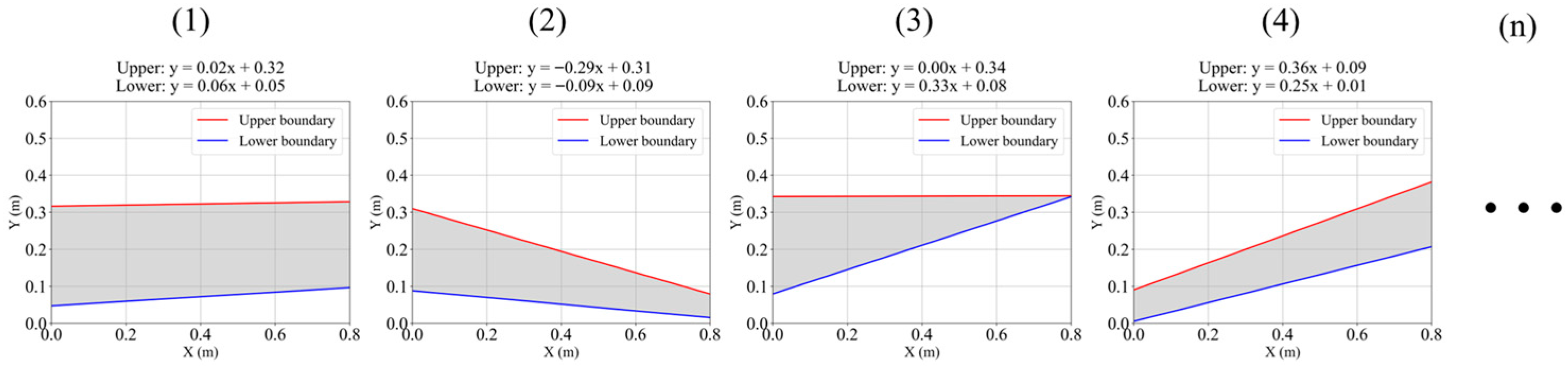

In both the pre-defined and post-defined models, a Cartesian X–Y coordinate system is established on the two-dimensional plane, with the boundary lines represented as two continuous lines within this coordinate system. For the pre-defined model, the upper and lower boundaries correspond to the topmost and bottommost particles of the interburden particle collection. For the post-defined model, two boundary lines are randomly generated within the range x, y ∈ (0, 0.8 m), with the upper boundary always positioned above the lower boundary, thereby representing the region of the specific particle collection. The morphology of randomly generated upper and lower boundaries is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The particle coordinate changes are recorded as , where denotes the particle coordinates, represents the stage during the ore-drawing process, and is the particle ID. Starting from the beginning of ore drawing, the coordinates of particles are recorded every time 10 particles are released, and each such recording is designated as one stage. In all ore-drawing simulation experiments, the total number of stages exceeds 200.

Additionally, 81 points are selected along the X-axis at 10 mm intervals starting from 0, ensuring that each X value maps to a unique Y value. Thus, each boundary line is characterized by the coordinate variations of 81 uniformly spaced particles, representing the morphological changes in the interburden before and after ore drawing. The selection method of the candidate particle set

is given as follows:

Here, = denotes the coordinates of the -th particle at the initial stage. represents the collection of all interburden particles, and is the -th sampling position along the X-axis. For each sampling point, particles belonging to the interburden group are searched within a tolerance of = 0.015.

If no particle is found within this range, the particle

with the minimum horizontal distance to the sampling point is selected and added to the candidate set

.

For each sampling point, the particles in

that have not yet been selected are evaluated to identify the particle with the maximum vertical coordinate

as the upper boundary particle, and the particle with the minimum vertical coordinate

as the lower boundary particle. The corresponding formulas are provided below. Once the boundary particles are determined, the dynamic changes in particle coordinates at each stage are recorded as dynamic inputs. Additionally, two static properties of the particles Radius (

) and Mass (

) are recorded as static inputs.

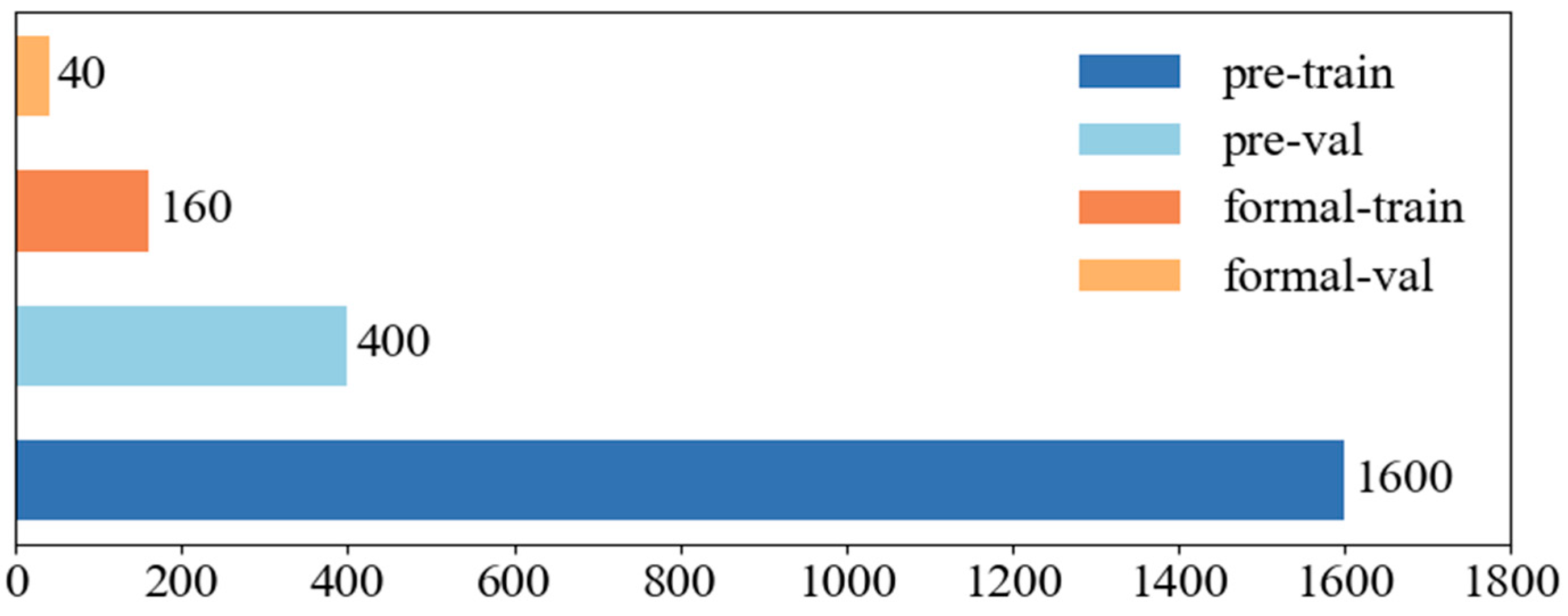

To achieve the initial objectives, the angle of repose determined from laboratory experiments was used to calibrate the parameters for numerical simulations, yielding the dataset required for this study. This dataset includes a large amount of post-defined interburden data and a smaller portion of pre-defined interburden data. Clearly, obtaining interface morphology data through autonomous delineation is relatively straightforward; however, post-defined interburden data cannot accurately reflect real conditions. A total of 2200 data samples were obtained, of which 2000 correspond to post-defined interburden and are used for pretraining, while 200 correspond to pre-defined interburden and are used for transfer learning. To ensure balanced evaluation of the subsequent network performance, 80% of the data in both pretraining and transfer learning were used for training, and 20% for validation. Detailed classification of data usage is presented in

Figure 6.

3. Model

Granular flow during the ore-drawing process is inherently a spatiotemporally evolving phenomenon. In this typical spatiotemporal coupling problem of ore particle transport prediction, traditional physical models are constrained by simplified mechanical assumptions, while data-driven methods (such as LSTM), struggle to capture the nonlinear interactions among particle ensembles. The Transformer architecture [

26], originally developed for natural language processing and time-series modeling, demonstrates unique advantages in sequence modeling tasks due to its self-attention mechanism and positional encoding system [

27,

28]. When applied to granular flow in ore drawing, the Transformer architecture enables joint modeling of the spatial positions of all particles at each stage, thereby uncovering the interaction and co-evolution patterns among particles. Its self-attention mechanism facilitates the capture of non-local dependencies, significantly enhancing the capability to model complex motion patterns.

3.1. Transformer Model

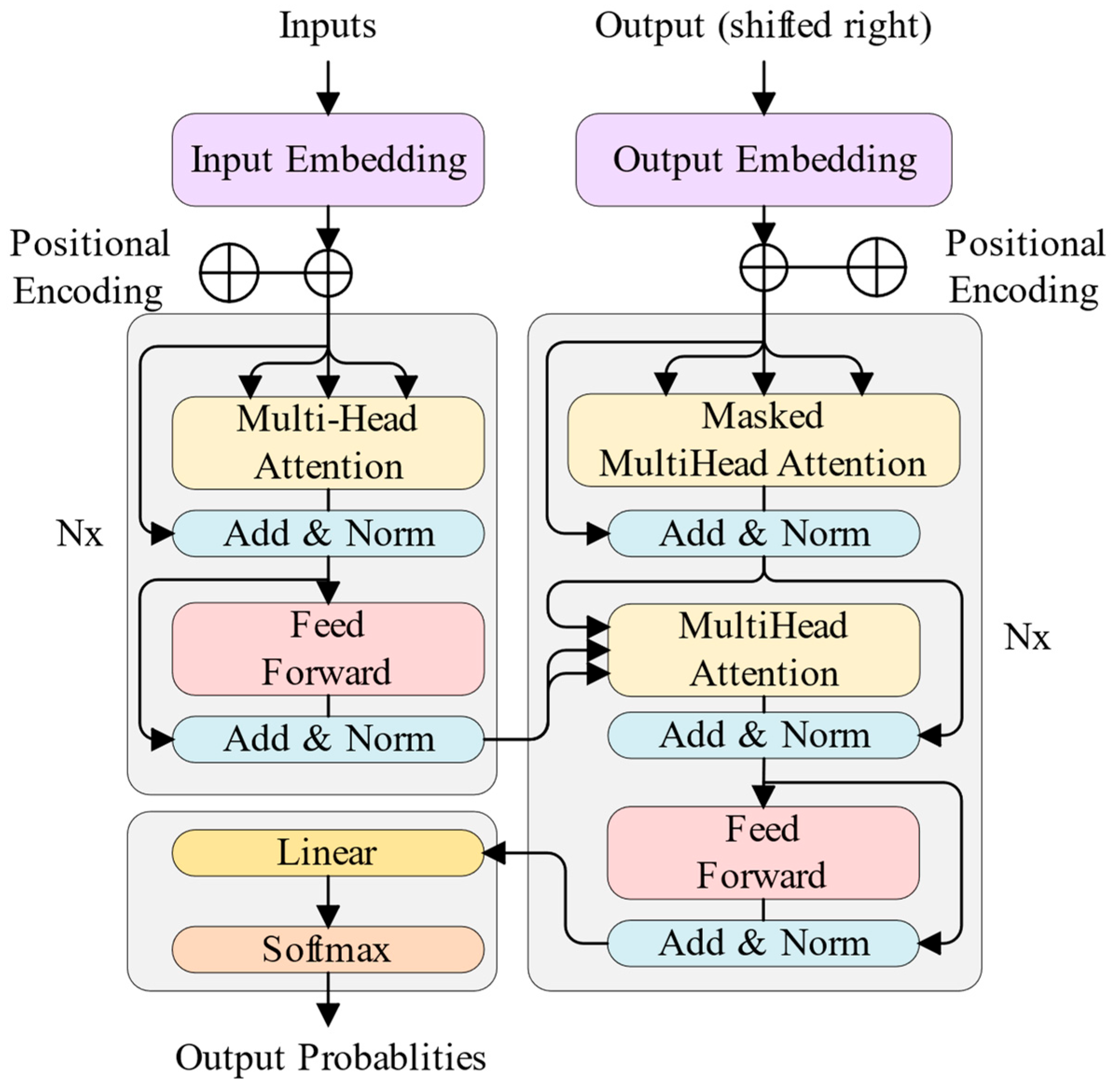

The fundamental architecture of the Transformer is illustrated in

Figure 7. It consists of an encoder and a decoder, both constructed by stacking N identical layers [

26]. The encoder is composed of two sublayers: (1) Multi-Head Self-Attention, which captures global dependencies among elements in the input sequence; and (2) the Position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN), which performs nonlinear transformations on features at each sequence position. Each sublayer adopts the standard structure of layer normalization → sublayer computation → residual connection, a design that substantially improves training stability and alleviates the vanishing gradient problem.

The decoder extends each layer into three sublayers: (1) Masked Multi-Head Self-Attention, where masking constrains each position to attend only to its preceding positions, thereby ensuring the causality of autoregressive generation; (2) Multi-Head Cross-Attention, where the queries are derived from the output of the preceding decoder sublayer and the keys/values are taken from the encoder output, thus enabling encoder–decoder information interaction; and (3) the Position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN).

In addition, the input and output modules include the Embedding Layer (which maps discrete symbols into dense vectors), Positional Encoding (which injects sequence order information through sinusoidal functions), and the final Linear and Softmax layers (which transform the decoder outputs into probability distributions over the target vocabulary). These components convert raw input text into representations processable by the model and generate the final outputs.

By eliminating recurrent and convolutional operations, this architecture relies purely on attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies, thereby overcoming the sequential constraints of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and the locality limitations of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs).

However, the original Transformer architecture exhibits significant limitations in predicting granular flow during ore drawing in caving methods. Its insufficient spatiotemporal modeling capacity prevents a unified representation of two fundamentally distinct physical processes: instantaneous particle–particle interactions, which follow the principle of spatial simultaneity, and the evolution of individual trajectories, which is strictly governed by temporal causality. The attention mechanism, lacking explicit physical constraints, may inadvertently introduce information leakage from future states, thereby violating the core law of temporal irreversibility in granular motion. At the feature fusion level, the model adopts a single, simplistic integration strategy, making it ineffective in jointly incorporating static particle attributes with dynamically evolving positional information. Consequently, the influence of material properties on particle behavior cannot be accurately captured. Moreover, the architecture lacks a state-transition mechanism, rendering it incapable of simulating the critical shift from motion to rest when particles reach the drawpoint. This deficiency restricts the model’s ability to reflect physical priors and the staged release characteristics inherent in granular discharge. These limitations collectively constrain the predictive accuracy and physical plausibility of the original architecture in modeling the transport of interburden boundary particles during ore drawing.

3.2. Improved Transformer Model

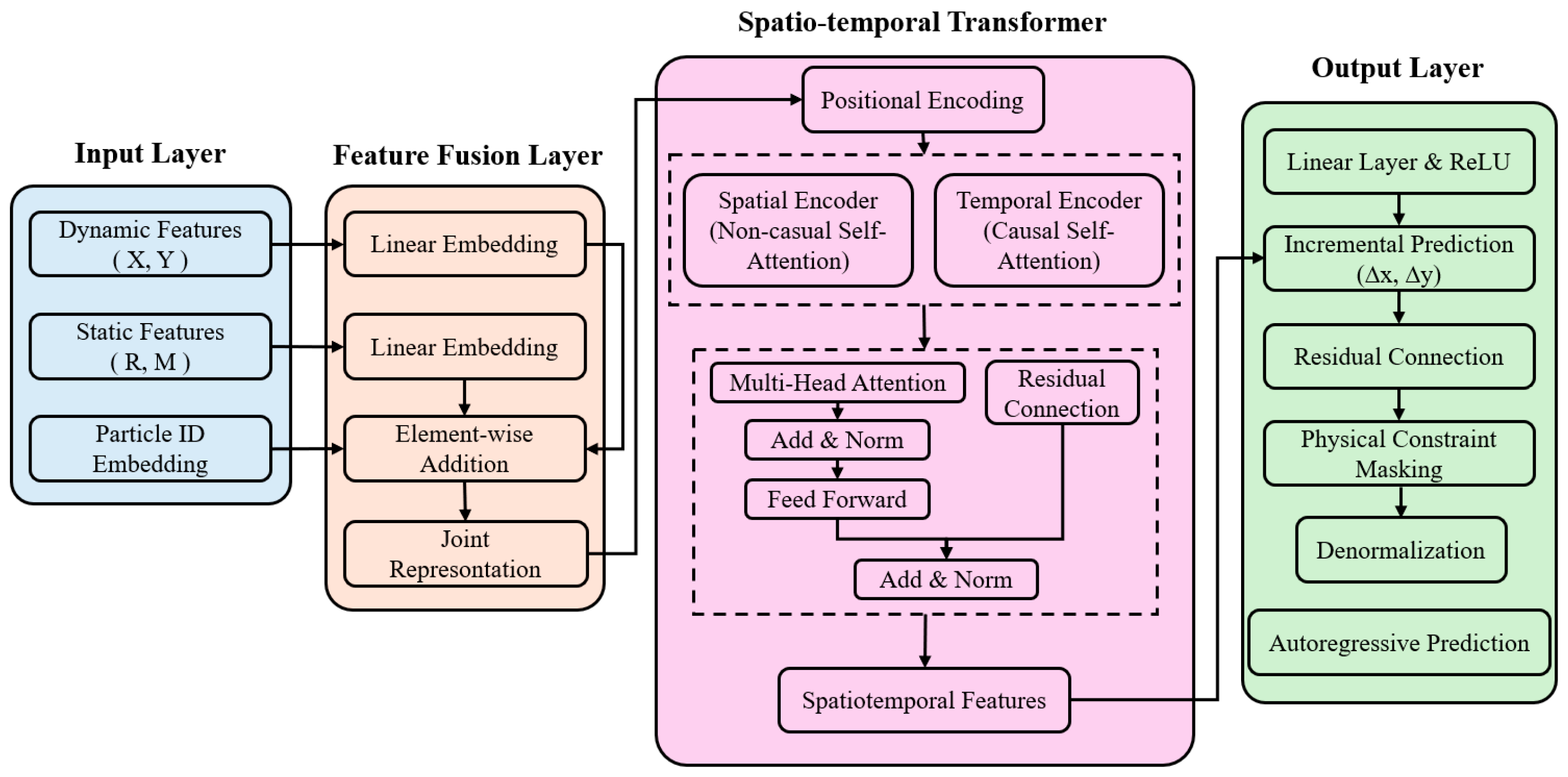

To overcome the limitations of the original Transformer in predicting ore–rock particle transport—namely, insufficient spatiotemporal modeling capacity, the lack of physical constraints in the attention mechanism, inadequate fusion of static and dynamic features, and the absence of a state-transition mechanism—this study proposes an improved Transformer model that integrates physical prior constraints. The overall model architecture is illustrated in

Figure 8.

3.2.1. Input Stage and Feature Fusion Embedding

At the input stage, the architecture retains only the particle spatial coordinates as dynamic features, while the particle and are treated as static features. Both static and dynamic features are independently normalized throughout the workflow to enhance numerical stability and generalization. This design discards redundant kinematic quantities that can be derived from positional differences, thereby reducing input dimensionality while emphasizing the physical attributes directly related to particle motion. In doing so, it avoids the accumulation of noise that could otherwise impair the accuracy of spatiotemporal modeling.

During the feature fusion embedding stage, the static features

and dynamic features

are linearly projected into a shared high-dimensional embedding space

. The transformation is defined as

where

denote the projection matrices for static and dynamic features, and

are the corresponding bias vectors.

To integrate static attributes into temporal sequence modeling, the static embedding

is replicated along the time dimension and added element-wise to the dynamic embedding

. This operation yields the joint representation

, which reflects the modulation effect of inherent particle properties on instantaneous motion:

In addition, particle ID embedding

is introduced, assigning each particle a unique learnable identifier. This mechanism captures individual physical heterogeneity and strengthens the model’s particle-level discrimination. The final feature input

is expressed as follows:

3.2.2. Spatio-Temporal Transformer

Within the backbone, the model adopts a Spatio-temporal Transformer structure composed of a Spatial Encoder (non-causal self-attention) and a Temporal Encoder (causal self-attention). The Spatial Encoder models instantaneous interactions among particles within a single time step, consistent with the principle of spatial simultaneity in particle motion. In contrast, the Temporal Encoder performs sequential modeling of trajectory evolution under the constraint of a causal mask

, ensuring that trajectory prediction strictly adheres to temporal causality and preventing information leakage from future states. The self-attention computation of the Temporal Encoder is defined as follows:

Here,

denote the query, key, and value matrices, respectively;

is the dimension of the key vectors; and

is an upper-triangular mask matrix that strictly prohibits access to future time steps. Temporal position information is explicitly injected through sinusoidal Positional Encoding (PE), defined as follows:

where

denotes the time step,

indexes the embedding dimension, and

is the dimensionality of the model embedding space.

3.2.3. Output Stage

At the output stage, the model adopts an incremental prediction strategy, predicting displacement increments

instead of absolute coordinates. Trajectories are iteratively generated using residual connections, ensuring that the prediction form remains consistent with the physical motion process. The formula is shown as follows:

Furthermore, to account for the physical process of state transitions during particle release in ore-drawing simulations, a Physical-Constraint-Masking (PCM) mechanism is introduced. In autoregressive prediction, once a particle is determined to be released at a given stage, its subsequent predicted positions are fixed at the release coordinates, and these positions are masked during loss computation. This ensures that particle state predictions adhere closely to the true evolutionary process.

Through these design choices, the improved spatiotemporal Transformer not only retains the original Transformer’s advantage in modeling global dependencies, but also incorporates innovative, physics-driven components—feature selection guided by physical priors, particle ID embedding, spatial–temporal dual encoding, incremental prediction, and release-state physical constraints. Collectively, these enhancements enable high-precision prediction of interburden boundary particle transport during ore drawing and physically consistent modeling of ore–rock granular flows, providing both theoretical support and a practical implementation pathway for intelligent prediction of complex granular systems.

5. Conclusions

To address the complex problem of predicting boundary particle migration during ore drawing using the caving method with interburden, this study systematically investigates dataset construction and model design, experimentally validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The primary conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

The dataset construction method proposed in this study employs numerical simulation experiments to achieve high-precision calibration of the angle of repose parameter. It establishes a single-hole ore-drawing numerical simulation dataset encompassing both “post-defined interburden models” and “pre-defined interburden models”. This approach effectively mitigates the challenge of insufficient data volume arising from difficulties in data acquisition under interburden conditions, and furthermore, delivers reliable support for model pre-training, transfer learning, and validation.

- (2)

The improved Transformer model proposed in this study incorporates a multi-layer feature fusion embedding module at the input stage to enhance the spatiotemporal feature representation capability for particle migration. Within the backbone network, the spatiotemporal attention mechanism is reinforced to capture long-range dependencies. The decoder structure is optimized at the output end to improve the modeling capacity for local dynamic variations. The refined model achieves a more comprehensive characterization of the migration processes resulting from complex interactions among particles.

- (3)

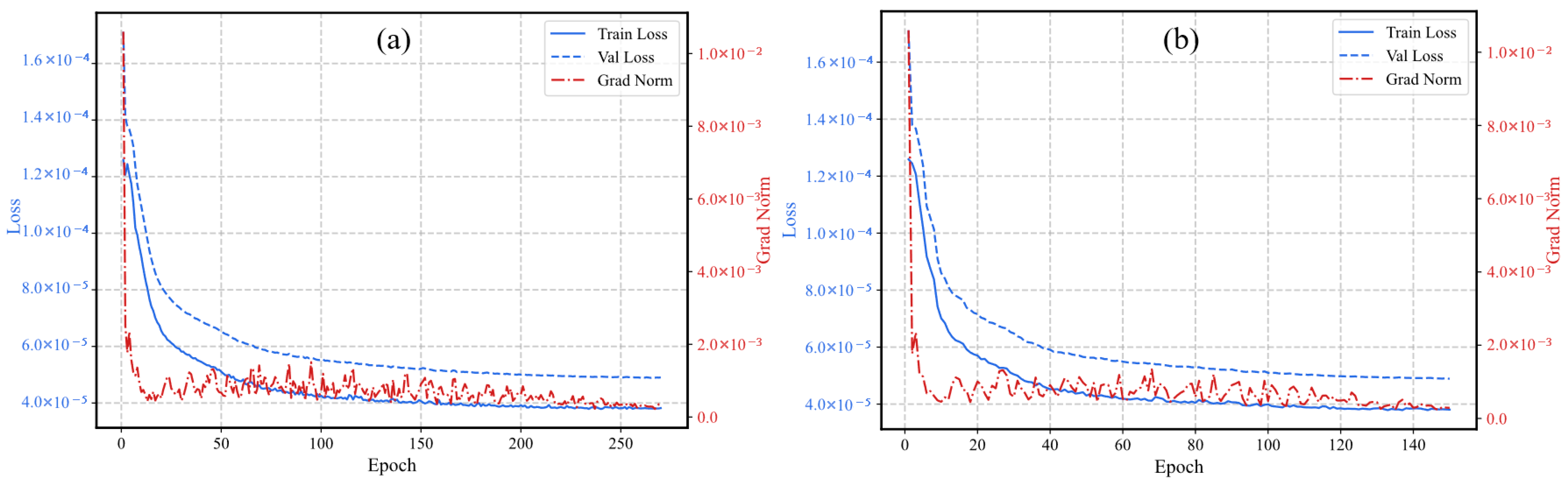

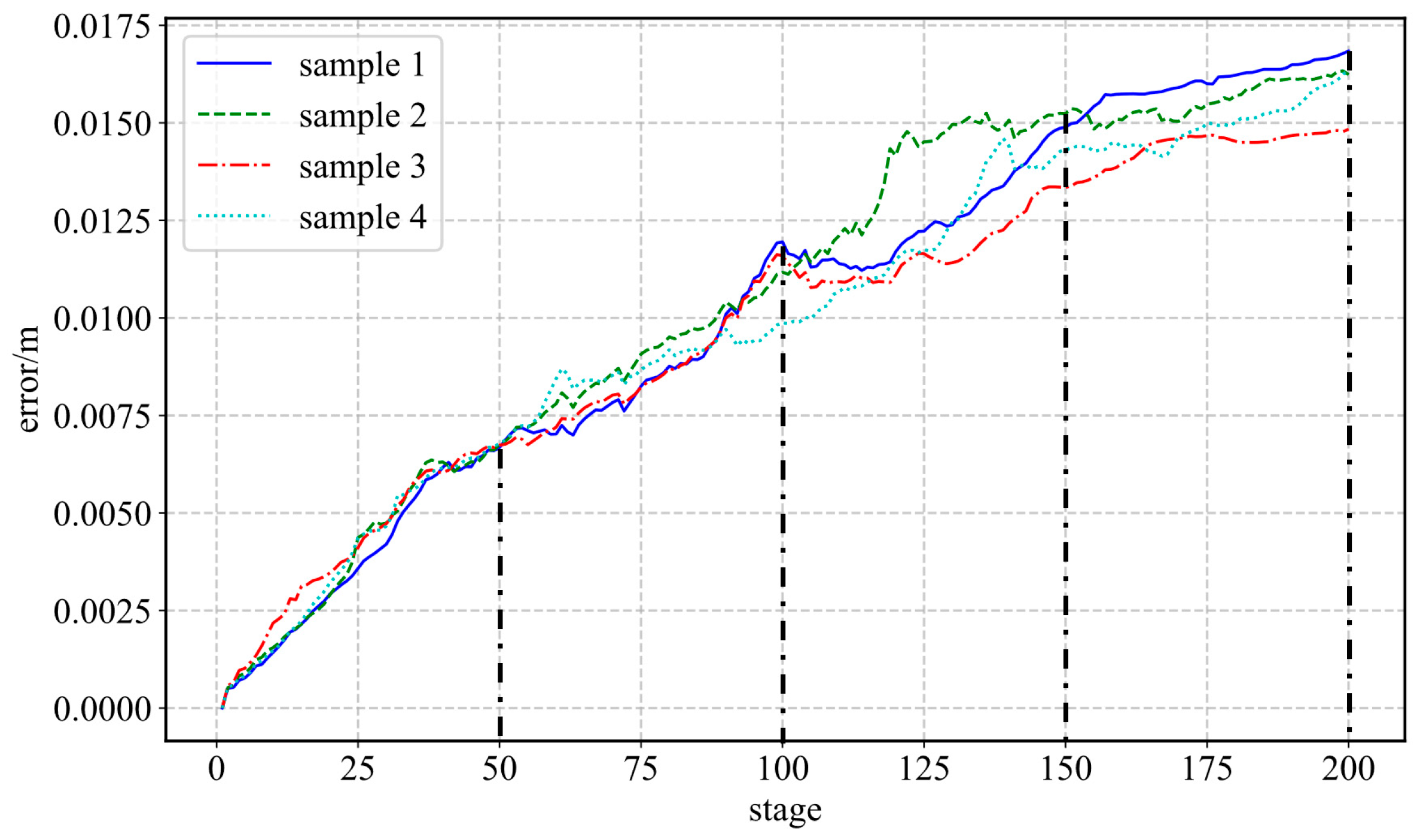

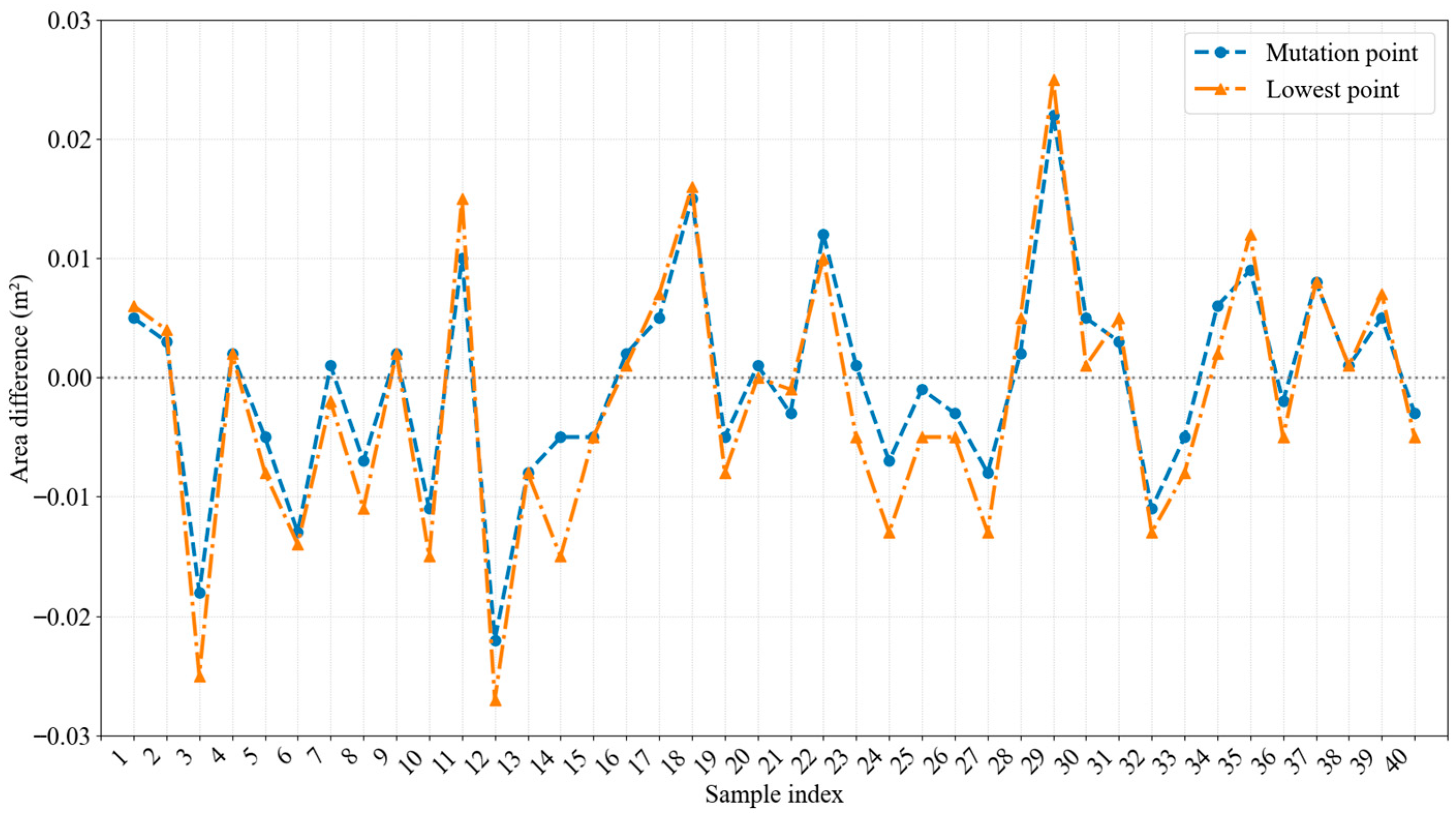

Operating in continuous prediction mode, the improved Transformer model demonstrates high prediction accuracy across various interburden samples within the dataset. It accurately reproduces the evolutionary trend of particle coordinates throughout the ore-drawing stages, indicating the model’s robust generalization performance. Concurrently, the model precisely identifies the critical stage numbers corresponding to changes in ore discharge grade. At these critical points, the average prediction error for interburden area is approximately 4%, confirming the model’s high reliability and practical value for forecasting key indicators.

Future research will prioritize the following directions: (1) extending the proposed framework to mines with different geological conditions, ore types, and ore-drawing configurations by expanding the model parameter space and incorporating mine-specific constraints, thereby enhancing the adaptability and generalizability of the approach to similar underground metal mines employing caving methods with interburden, and (2) continuously enriching the dataset by integrating field-measured data and high-fidelity numerical simulation results from different mining sites and further optimizing model performance through transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques, with the aim of achieving more robust, efficient, and broadly applicable predictions of boundary particle migration.