Experimental Investigation on Degree of Desaturation and Permeability Coefficient for Air-Injection-Desaturated Sandy Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modified Test Devices

2.2. Materials

2.3. Sample Preparation and Test Conditions

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

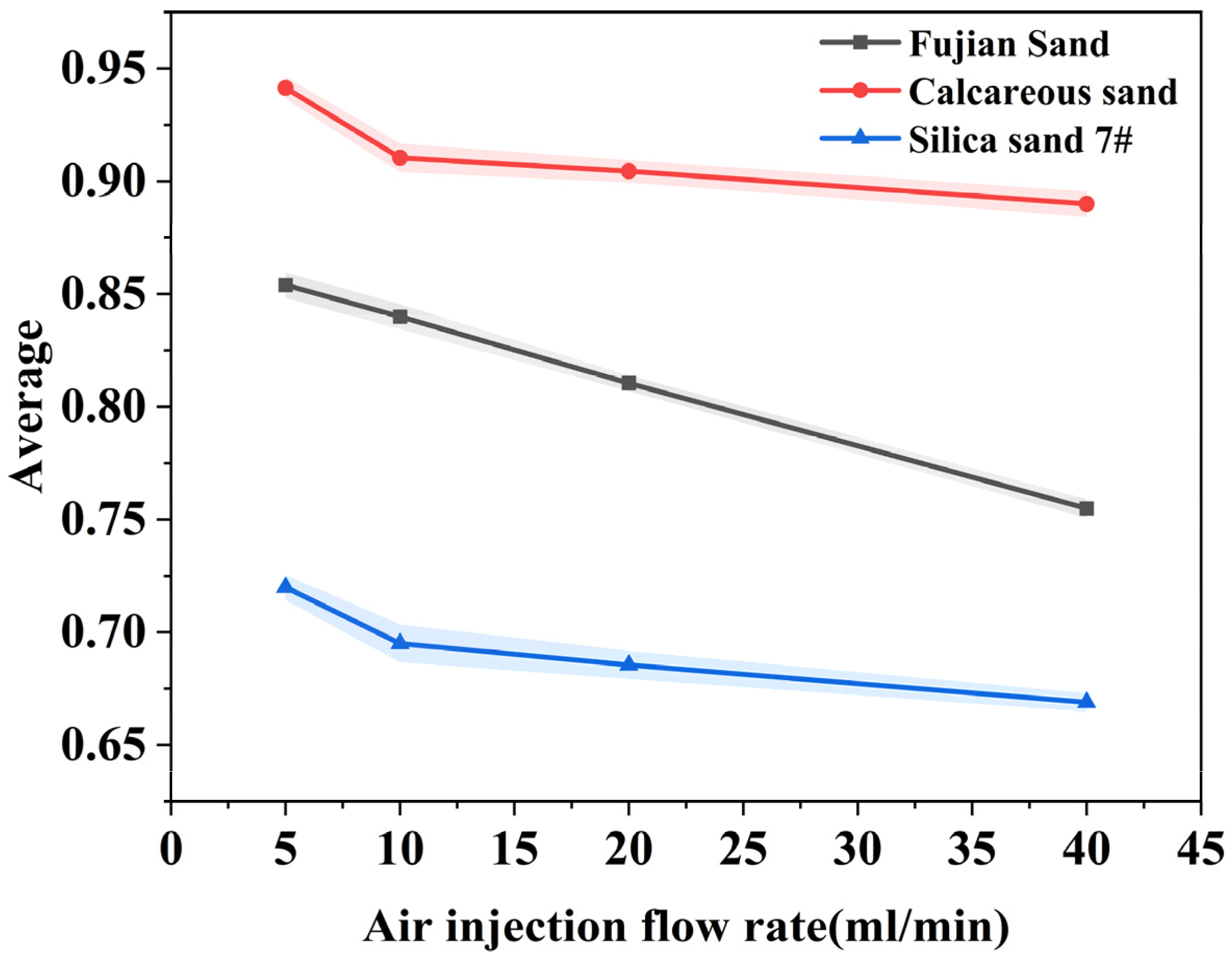

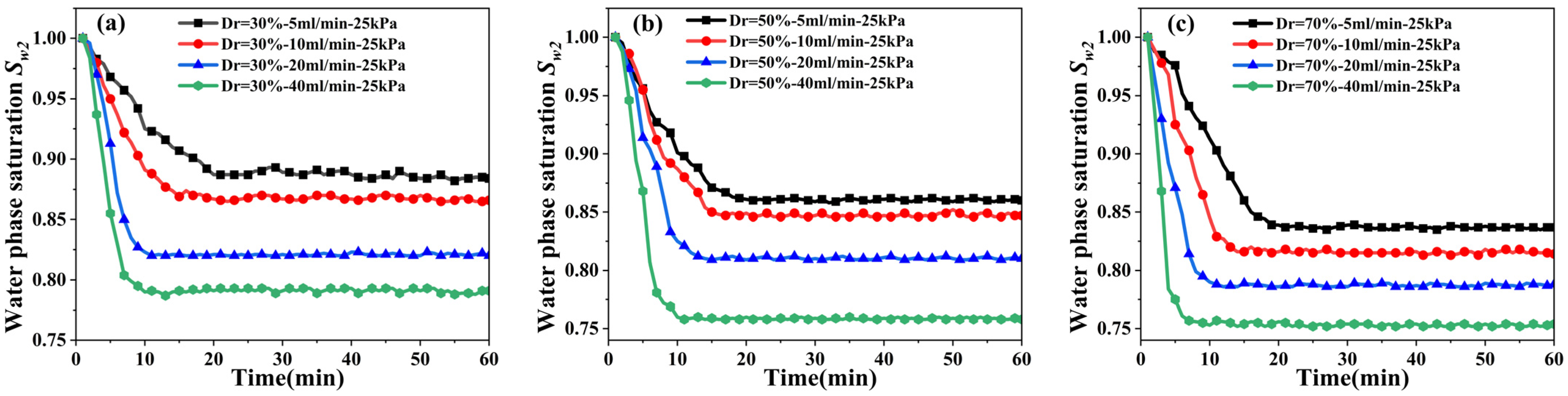

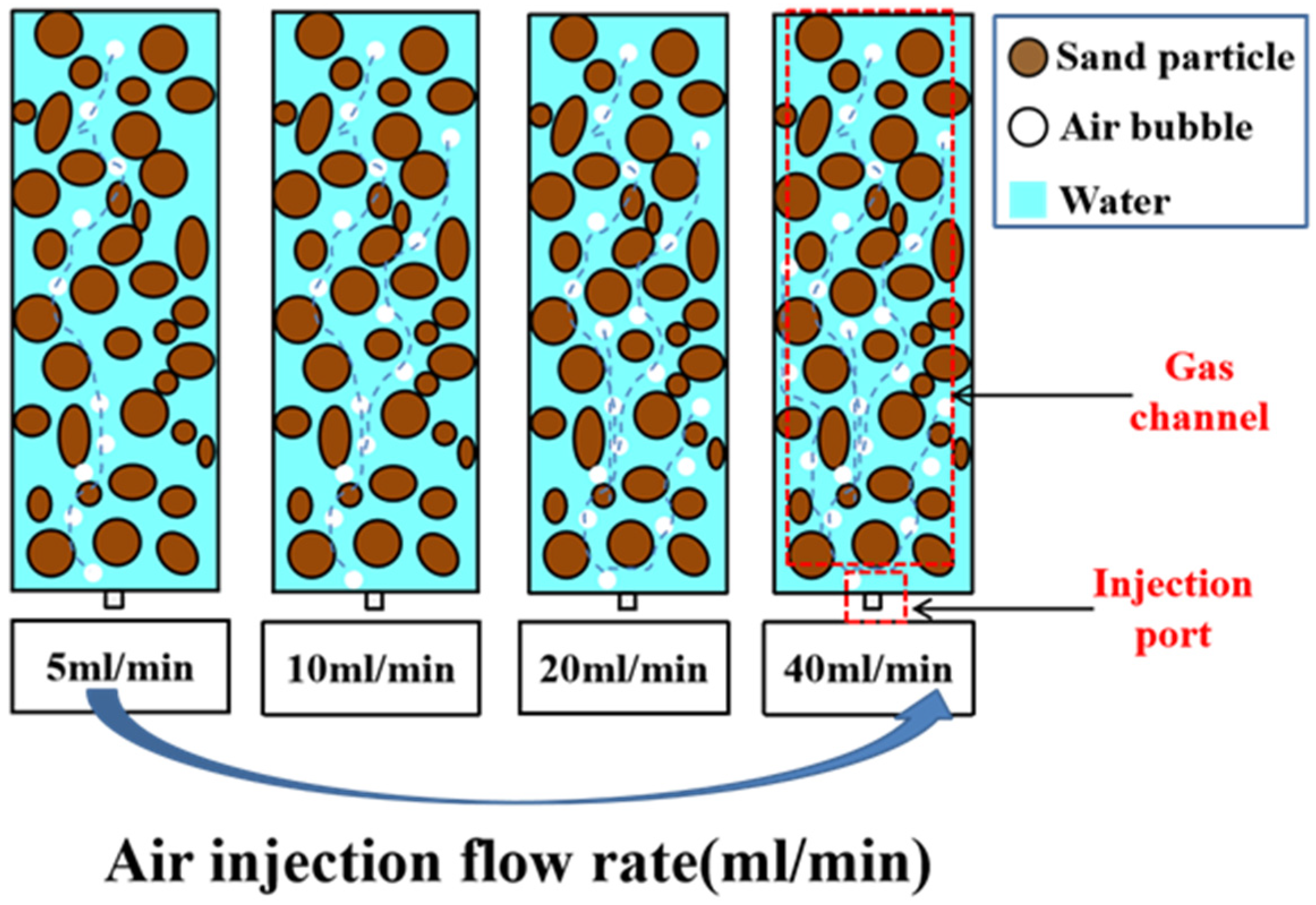

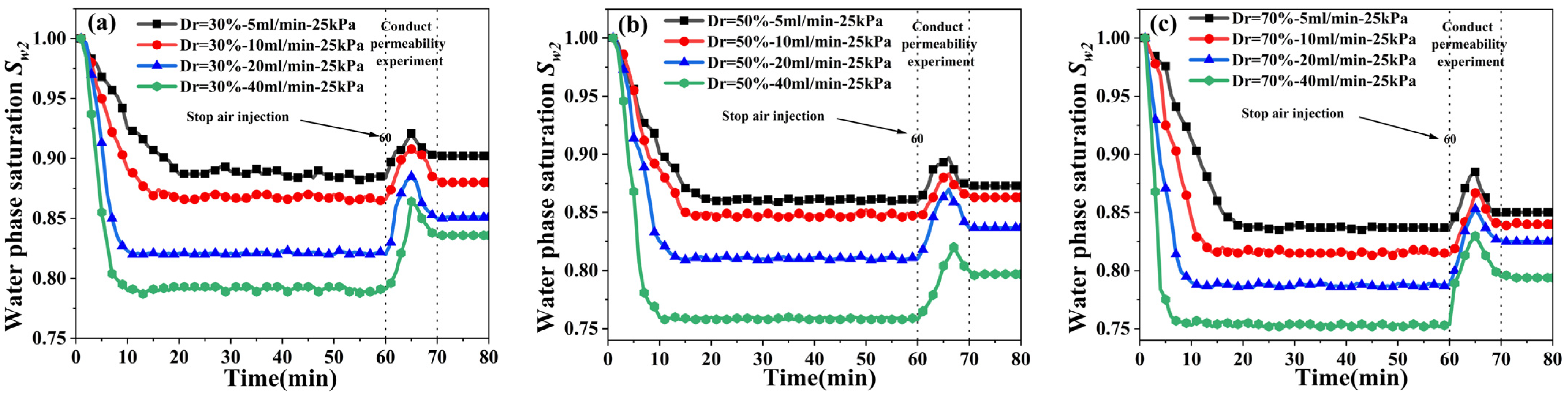

3.1. Effect of Air Injection Flow Rate on Degree of Saturation

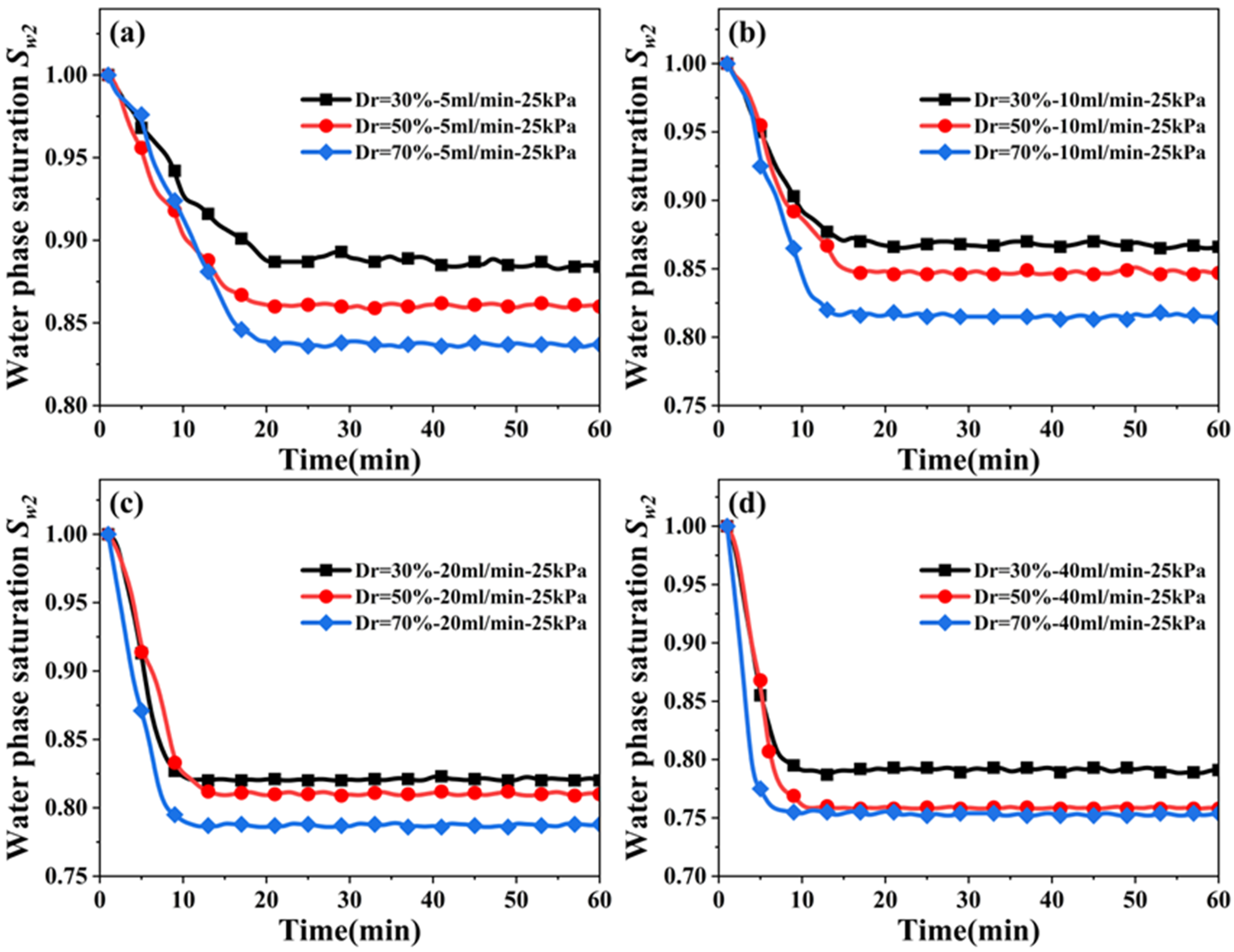

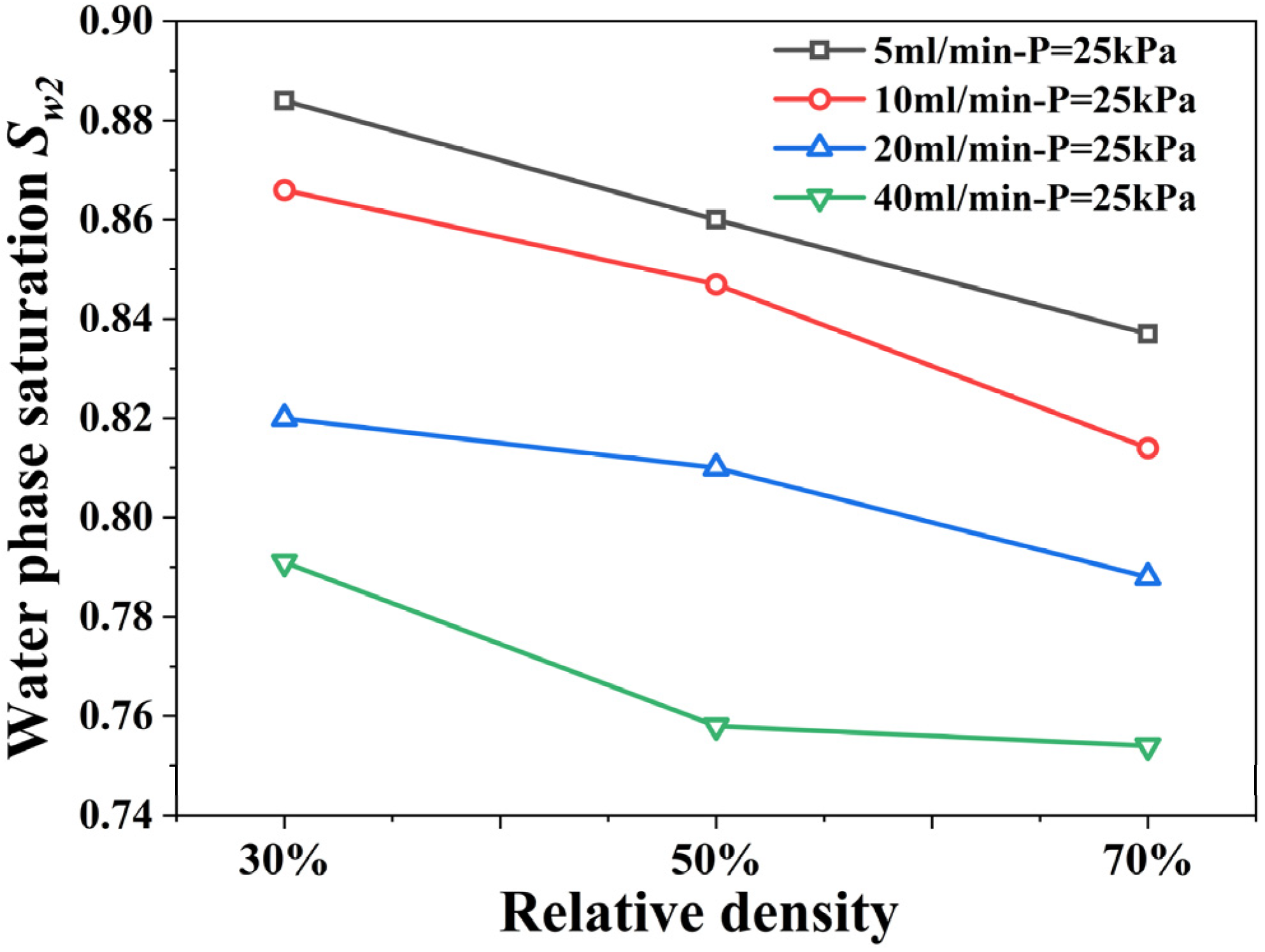

3.2. Effect of Relative Density on Degree of Saturation

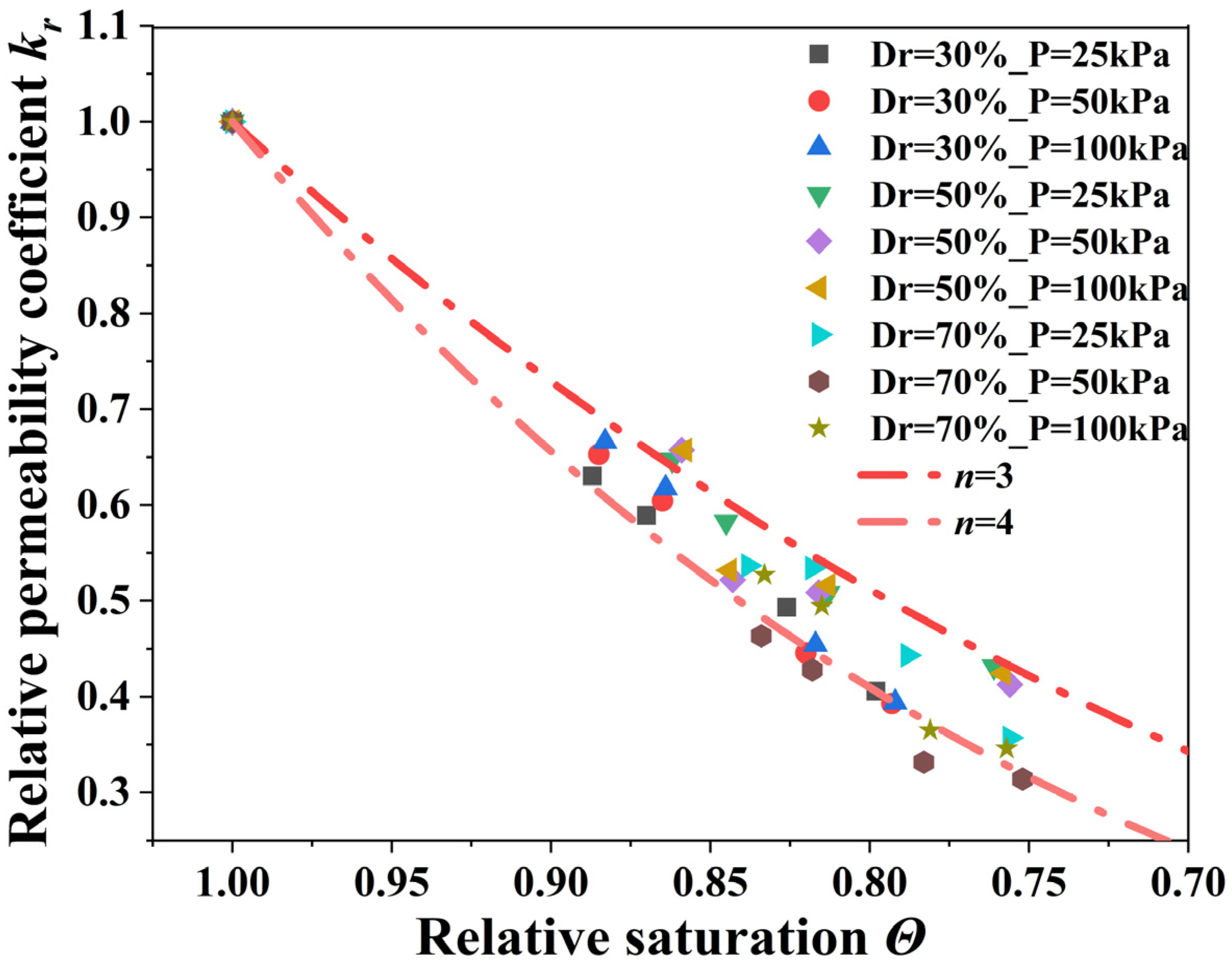

3.3. Influence of Degree of Saturation on Permeability Coefficient

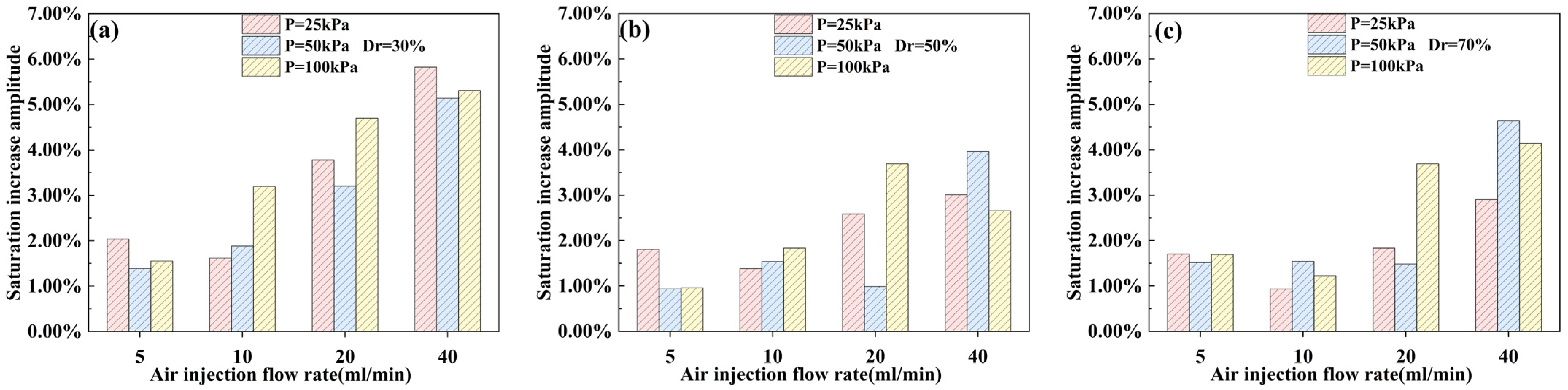

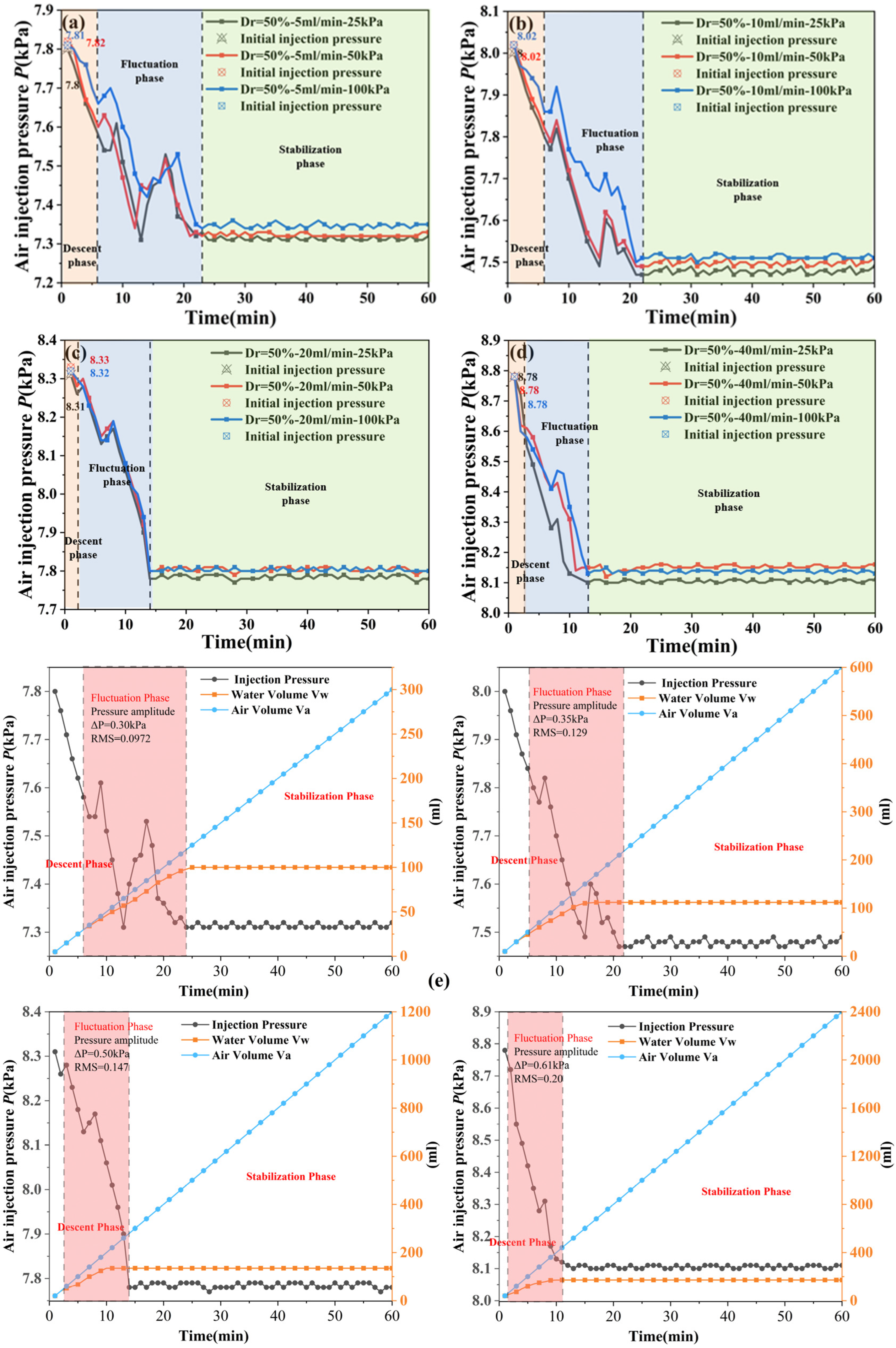

4. Influence of Overburden Pressure on Air Injection Pressure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fipps, G.; Skaggs, R.W.; Nieber, J.L. Drains as a Boundary Condition in Finite Elements. Water Resour. Res. 1986, 22, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshchinsky, D.; Yu, H.S.; Salgado, R. Limit Analysis versus Limit Equilibrium for Slope Stability. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1998, 125, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubal, S.; Sapari, N.B.; Harahap, I.S. Numerical Simulation of Groundwater Rising Due to Rainfall at Far Field in Triggering Landslide. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, K.; Egusa, T.; Ikka, T.; Yamashita, H.; Imaizumi, F. Effects of Shallow Groundwater on Deep Groundwater Dynamics in a Slow-Moving Landslide Site. Int. J. Eros. Control Eng. 2023, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, J.; Moya, J.; Ledesma, A.; Lloret, A.; Gili, J.A. Prediction of Ground Displacements and Velocities from Groundwater Level Changes at the Vallcebre Landslide (Eastern Pyrenees, Spain). Landslides 2005, 2, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yin, K.; Cao, Y.; Intrieri, E.; Ahmed, B.; Catani, F. Displacement Prediction of Step-like Landslide by Applying a Novel Kernel Extreme Learning Machine Method. Landslides 2018, 15, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Yang, D.; Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tang, B. Deformation Responses of Landslides to Seasonal Rainfall Based on InSAR and Wavelet Analysis. Landslides 2022, 19, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, M.; Simoni, A. Groundwater and Ground Displacement Monitoring in the Source Area of the Montecchi Earthflow (Northern Apennines, Italy). Riv. Ital. Geotec. 2016, 50, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Li, Q.H.; Cheng, X.S.; Ha, D.; Shi, J.C.; Shi, X.R.; Lei, Y.W. Diaphragm Wall Deformation and Ground Settlement Caused by Dewatering before Excavation in Strata with Leaky Aquifers. Géotechnique 2024, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Song, C.M. Prediction of the Soil Permeability Coefficient of Reservoirs Using a Deep Neural Network Based on a Dendrite Concept. Processes 2023, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.E.; Lee, S.R. Instability of Unsaturated Soil Slopes Due to Infiltration. Comput. Geotech. 2001, 28, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Santoso, V.A.; Leong, E.C.; Ng, Y.S.; Hua, C.J. Performance of Horizontal Drains in Residual Soil Slopes. Soils Found. 2011, 51, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Sangam, H.P. Durability of HDPE Geomembranes. Geotext. Geomembr. 2002, 20, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowska, M.; Lipiński, M.; Nasiłowski, K.; Osiński, P. Shear Strength and Seepage Control of Soil Samples Used for Vertical Barrier Construction—A Comparative Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Salmasi, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Arvanaghi, H. Weep Hole and Cut-off Effect in Decreasing of Uplift Pressure (Case Study: Yusefkand Mahabad Diversion Dam). J. Civ. Eng. Urban. 2012, 2, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Kong, X.J.; Zou, D.G.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, Z.Q. Linear Elastic and Plastic-Damage Analyses of a Concrete Cut-off Wall Constructed in Deep Overburden. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 69, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Zhang, J.Q.; Chen, X.S.; Xu, Z.Y.; Su, D.; Song, R.; Cui, T. Experimental Investigation and Mechanical Model for Assembled Joints of Prefabricated Two-Wall-in-One Diaphragm Walls. Eng. Struct. 2023, 275, 115285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Long, Z.; He, L.; Ye, S.; Mao, Y. Hydro-Physical Properties and Durability Study of Cement Slurry Material Based on Loess. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Mermoud, A. Comparison of Models for Predicting Hydraulic Conductivity Functions from Soil Retention Data. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2001, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.M.; Wang, C.S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, B. Laboratory Tests on the Characteristics of Air-Permeation in Unsaturated Shanghai Soft Soil. J. Eng. Geol. 2009, 17, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.M.; Qian, L.X.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B. Predicting Coefficient of Permeability from Soil-Water Characteristic Curve for Shanghai Soft Soil. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2005, 27, 1262–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda, C.; Culligan, P.J.; Germaine, J.T. Centrifuge modeling of air sparging—A study of air flow through saturated porous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 72, 179–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Qin, C.Z.; Sarajpoor, S.; Chen, R.Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, Z.J. The Influence of Sand Pore Structure on Air Migration During Air-Injected Desaturation Process. Buildings 2024, 14, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.L. Research of Intercepting Groundwater with Compressed Air for Landslide Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda-Cano, S.; Garcia-Aristizabal, E.F.; Vega-Posada, C.A. Numerical Study of a Desaturation Process by Air Injection in Sandy Soil. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 337, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Sun, H.Y.; Wei, Z.L.; Shang, Y.Q.; Yan, X. Influence of the Features of the Unsaturated Zone on the Air Injection Method in a Slope. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Geotech. Eng. 2020, 173, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.L.; Sun, H.Y.; Shang, Y.Q. Air-Filled Drainage Method in Loose Accumulation Soil Slope. J. Jilin Univ. Sci. Ed. 2013, 43, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.D.; Sun, H.Y.; Kang, J.W.; Du, L.L. Experimental Investigation of Seepage Barrier Effect by Air-Inflation in Soil. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. 2014, 48, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.F. Simulation Study on Mechanism of Inflation Drainage Method in Slope. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Shang, Y.; Lü, Q.; Jiang, H.; Wei, Z. Experimental Study of Groundwater Level Variation in Soil Slope Using Air-Injection Method. Géotechnique Lett. 2018, 8, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.L.; Sun, H.Y.; Shang, Y.Q.; Kang, J.W. Numerical Simulations of Water Intercepting and Drainage Associated with Air Filling for Landslide Treatment. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2014, 33, 2628–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Z. Numerical Simulation of the Technology of Intercepting and Draining Water with Compressed Air for Landslide. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Shang, Y.Q.; Wu, G.; Wei, Z.L. Investigation of the Formation Process of a Low-Permeability Unsaturated Zone by Air Injection Method in a Slope. Eng. Geol. 2018, 245, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.X. Research on Anti Seepage of Foundation Pit Based on Inflatable Interception and Drainage Technology. Master’s Thesis, Shijiazhuang Tiedao University, Shijiazhuang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Hu, L.M.; Wu, X.F.; Liu, Y.; Meegoda, J.N.; Gao, S.Y. Physical Modeling of Air Flow During Air Sparging Remediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3883–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Noah, I.; Friedman, S.P.; Berkowitz, B. Air Injection Into Water-Saturated Granular Media—A Dimensional Meta-Analysis. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2022WR032125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajpoor, S.; Chen, Y.M.; Han, Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Fu, Z.L.; Ma, K. Experimental Comparison of Air Entrapment Capacity in Sandy Soils for Liquefaction Mitigation: Evaluating Air Injection Method Efficiency in Soil Desaturation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 190, 109166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Friis, H.A.; Jettestuen, E.; Helland, J.O. A Level Set Approach to Ostwald Ripening of Trapped Gas Bubbles in Porous Media. Transp. Porous Media 2022, 145, 441–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Kong, D.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Y.P.; Zhu, B. Experimental Investigation into Gas Migration Mechanism in Submarine Sandy Sediments at Pore-Scale. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2025, 17, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Georgiadis, A.; Brussee, N.; Coorn, A.; Van Der Linde, H.; Dietderich, J.; Alpak, F.O.; Eriksen, D.; Mooijer-van Den Heuvel, M.; Appel, M.; et al. Capillarity and Phase-Mobility of a Hydrocarbon Gas–Liquid System. Oil Gas Sci. Technol.-Rev. D’IFP Energ. Nouv. 2021, 76, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Lu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, H. A Review on Measurement of the Dynamic Effect in Capillary Pressure. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.G. Unsaturated Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 286–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmay, S. On the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1954, 35, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, A.T. Measurement of Water and Air Permeability in Unsaturated Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1957, 21, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; McCartney, J.S. Drained Seismic Compression of Unsaturated Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; McCartney, J.S. Undrained Seismic Compression of Unsaturated Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2021, 147, 04020145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Bao, Z.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Peng, P. Investigation of the Water-Retention Characteristics and Mechanical Behavior of Fibre-Reinforced Unsaturated Sand. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.D.; Wu, Y.K.; Hao, R.M.; Qiao, X.L.; Wang, S.X.; Si, X.N. A Calculation Model for Unsaturated Permeability and Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Sandy Soils Considering Pore Distribution. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Genuchten, M.T. A Closed-form Equation for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, X.C.; Pei, X.J.; Ren, G.F. Effect of the Particle Size Composition and Dry Density on the Water Retention Characteristics of Remolded Loess. Minerals 2023, 12, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, W.; Kong, D.; Wang, L.; Zhu, B. Experimental Study on Mechanisms Governing Gas Migration in Saturated Sands and Resultant Soil Deformation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Sand | Specific Gravity Gs | Minimum Void Ratio emin | Maximum Void Ratio emax | Effective Particle Size d10 (mm) | Median Particle Size d50 (mm) | Uniformity Coefficient Cu | Curvature Coefficient Cc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian sand | 2.65 | 0.380 | 0.702 | 0.173 | 0.7 | 5.012 | 1.072 |

| Calcareous sand | 2.79 | 0.830 | 1.110 | 0.185 | 0.425 | 2.440 | 0.940 |

| Silica sand 7# | 2.64 | 0.593 | 0.972 | 0.100 | 0.150 | 1.700 | 0.994 |

| Test Sand | Test Groups | Relative Density Dr (%) | Air Injection Flow Rate (mL/min) | Overburden Pressure, P (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian sand | I | 30 | 5, 10, 20, 40 | 25, 50, 100 |

| II | 50 | 5, 10, 20, 40 | ||

| III | 70 | 5, 10, 20, 40 | ||

| Calcareous sand | IV | 50 | 5, 10, 20, 40 | 100 |

| Silica sand 7# | V | 50 | 5, 10, 20, 40 | 100 |

| Test ID | Relative Density Dr (%) | Air Injection Flow Rate (mL/min) | Overburden Pressure (kPa) | Water Phase Saturation (Sw1) | Water Phase Saturation (Sw2) | Coefficient of Variation (CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1-1 | 30 | 5 | 25 | 0.887 | 0.884 | 0.24% |

| 50 | 0.885 | 0.883 | 0.16% | |||

| 100 | 0.883 | 0.880 | 0.24% | |||

| I1-2 | 10 | 25 | 0.870 | 0.866 | 0.33% | |

| 50 | 0.865 | 0.862 | 0.25%% | |||

| 100 | 0.864 | 0.862 | 0.16% | |||

| I1-3 | 20 | 25 | 0.826 | 0.820 | 0.52% | |

| 50 | 0.820 | 0.816 | 0.35% | |||

| 100 | 0.817 | 0.815 | 0.17% | |||

| I1-4 | 40 | 25 | 0.798 | 0.795 | 0.27% | |

| 50 | 0.793 | 0.793 | 0.00% | |||

| 100 | 0.792 | 0.794 | 0.18% | |||

| II2-1 | 50 | 5 | 25 | 0.862 | 0.860 | 0.16% |

| 50 | 0.859 | 0.856 | 0.25% | |||

| 100 | 0.858 | 0.852 | 0.50% | |||

| II2-2 | 10 | 25 | 0.845 | 0.847 | 0.17% | |

| 50 | 0.843 | 0.846 | 0.25% | |||

| 100 | 0.844 | 0.842 | 0.16% | |||

| II2-3 | 20 | 25 | 0.813 | 0.810 | 0.26% | |

| 50 | 0.816 | 0.809 | 0.61% | |||

| 100 | 0.813 | 0.808 | 0.44% | |||

| II2-4 | 40 | 25 | 0.761 | 0.758 | 0.28% | |

| 50 | 0.756 | 0.759 | 0.28% | |||

| 100 | 0.758 | 0.756 | 0.19% | |||

| III3-1 | 70 | 5 | 25 | 0.838 | 0.834 | 0.34% |

| 50 | 0.834 | 0.830 | 0.34% | |||

| 100 | 0.833 | 0.828 | 0.43% | |||

| III3-2 | 10 | 25 | 0.818 | 0.814 | 0.35% | |

| 50 | 0.818 | 0.815 | 0.26% | |||

| 100 | 0.815 | 0.812 | 0.26% | |||

| III3-3 | 20 | 25 | 0.788 | 0.788 | 0.00% | |

| 50 | 0.783 | 0.785 | 0.18% | |||

| 100 | 0.781 | 0.787 | 0.54% | |||

| III3-4 | 40 | 25 | 0.756 | 0.754 | 0.19% | |

| 50 | 0.752 | 0.755 | 0.28% | |||

| 100 | 0.757 | 0.752 | 0.47% | |||

| IV4-1 | 50 | 5 | 100 | 0.938 | 0.945 | 0.53% |

| IV4-2 | 10 | 0.915 | 0.906 | 0.70% | ||

| IV4-3 | 20 | 0.901 | 0.908 | 0.55% | ||

| IV4-4 | 40 | 0.894 | 0.886 | 0.64% | ||

| V5-1 | 50 | 5 | 100 | 0.724 | 0.716 | 0.79% |

| V5-2 | 10 | 0.701 | 0.689 | 1.22% | ||

| V5-3 | 20 | 0.690 | 0.681 | 0.93% | ||

| V5-4 | 40 | 0.672 | 0.666 | 0.63% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Qin, C.; Sarajpoor, S.; Wang, Q. Experimental Investigation on Degree of Desaturation and Permeability Coefficient for Air-Injection-Desaturated Sandy Soil. Processes 2026, 14, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010080

Zhang M, Chen Y, Qin C, Sarajpoor S, Wang Q. Experimental Investigation on Degree of Desaturation and Permeability Coefficient for Air-Injection-Desaturated Sandy Soil. Processes. 2026; 14(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mengmeng, Yumin Chen, Chengzhao Qin, Saeed Sarajpoor, and Qiongting Wang. 2026. "Experimental Investigation on Degree of Desaturation and Permeability Coefficient for Air-Injection-Desaturated Sandy Soil" Processes 14, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010080

APA StyleZhang, M., Chen, Y., Qin, C., Sarajpoor, S., & Wang, Q. (2026). Experimental Investigation on Degree of Desaturation and Permeability Coefficient for Air-Injection-Desaturated Sandy Soil. Processes, 14(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010080