1. Introduction

In the field of process control, ensuring the operational stability and product quality consistency of industrial processes has long been regarded as a core fundamental requirement. However, with the increasing global emphasis on energy conservation, carbon emission reduction, and sustainable manufacturing, the modern process industry is gradually pursuing higher-level control objectives. A new direction has emerged, one that involves minimizing operational energy consumption to the greatest extent possible while maintaining product quality, thereby enhancing the overall economic and environmental performance of the system. To meet this demand, advanced control technologies such as model predictive control (MPC) and real-time optimization (RTO) have been developed and applied. MPC operates on the principle of leveraging a mathematical process model to predict the system’s dynamic responses over a future horizon, then iteratively optimizing the control input sequence in a rolling manner while satisfying process constraints to drive the system toward setpoints and optimize operational performance [

1]. Having established a pivotal role in chemical process control, MPC excels at addressing multi-variable coupling and complex operational constraints, as supported by foundational and review studies in the field [

2,

3]. Similarly grounded in a process model-based framework, RTO focuses on real-time adjustment of process operating setpoints to optimize economic or environmental objectives. It has emerged as a prominent research hotspot in recent years, with gradual industrial deployment underpinned by theoretical advancements and practical validation [

4,

5]. Notably, in recent advancements, a range of artificial intelligence methods have been increasingly integrated into RTO’s modeling and optimization processes, marking a key trend in enhancing its adaptability and performance [

6]. These technologies have demonstrated significant advantages in industrial practice; however, they generally rely on complex modeling processes, require substantial computational resources for real-time operation, and impose strict requirements on the maintenance of model accuracy. This characteristic greatly limits their application flexibility in scenarios where process parameters fluctuate frequently or modeling conditions are harsh.

Against this backdrop, self-optimizing control (SOC) has emerged as an ideal alternative for achieving near-optimal process operation [

7,

8], thanks to its more straightforward implementation. The concept of SOC was first formally proposed by Skogestad in 2000 [

9]. Unlike MPC and RTO, SOC does not require complex online optimization calculations or high-fidelity dynamic process models. Its core feature lies in offline identifying a set of self-optimizing controlled variables (SOCVs) that have a direct and stable correlation with the system’s optimal operating state, enabling online operation via standard PI/PID controllers without real-time optimization or high-fidelity dynamic models. Subsequent studies have advanced SOC in distinct technical directions. One direction is to refine SOC’s design methods and apply them to various controlled units. For example, Ye and Skogestad [

10] extended static SOC to dynamic unconstrained batch processes through the development of a structure-constrained controlled variable selection approach with a convex formulation, validated in fed-batch reactors and batch distillation columns. Schultz et al. [

11] emphasized the critical role of nominal operating point selection, proposing a method to simultaneously optimize SOCVs and their setpoints, thereby significantly reducing worst-case and average economic losses in reactor-distillation and cumene production processes. Alves et al. [

12] developed metamodel-based numerical techniques for SOC, using the Kriging method to build surrogate models that simplify the selection of optimal controlled variables for large-scale nonlinear processes. The other direction focuses on integrating SOC with existing control frameworks or the early design stage. Graciano et al. [

13] integrated SOC with RTO/MPC via a zone control strategy, addressing suboptimal operation induced by low-frequency RTO setpoint updates and validating it in ammonia production and BTX separation processes. Zhang et al. [

14] systematically embedded SOC into the early plant design phase by incorporating process structural, parametric, and control-related variables, verifying its effectiveness in an extractive distillation process with preconcentration. These advances collectively broaden SOC’s applicability and enhance its performance, further solidifying its role as a versatile alternative to complex advanced control technologies.

Nevertheless, despite its prominent advantages, the practical application of SOC still faces a core bottleneck: the rational selection of SOCVs. The performance of SOC largely depends on whether the selected SOCVs can accurately reflect the system’s optimal operating state. If the SOCVs are improperly selected, maintaining them at constant values will not only fail to achieve energy savings but may even lead to deviations in product quality or operational instability. Traditional SOCV selection methods mostly rely on engineering experience or heuristic rules [

15], lacking a systematic approach and scientific rigor. This issue is more pronounced in complex multi-variable processes.

To address the above problem, this paper proposes an SOCV selection method based on the genetic programming (GP) algorithm and provides a detailed explanation with a case study on the control of a dividing-wall column (DWC) separating an ethanol (E)/propanol (P)/butanol (B) ternary mixture. The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 elaborates on the GP-based SOC scheme design method;

Section 3 introduces the DWC case and evaluates the effectiveness of the proposed GP-based method with this case;

Section 4 conducts relevant discussions; and

Section 5 presents the research conclusions.

3. Employing the GP-Based Design Method to Derive a SOC Scheme for the DWC Separating an E/P/B Ternary Mixture

3.1. Steady State Design of the DWC Separating the Ternary Mixture of E/P/B

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed GP-based SOC scheme design method, this study conducts a case study using a DWC dedicated to separating the ternary mixture of E/P/B (EPB DWC). Under standard atmospheric pressure, the boiling points of E, P, and B are 351.6 K, 370.3 K, and 390.8 K, respectively. This DWC is set with a top pressure of 1 atm and a pressure drop of 0.0068 atm per stage. It employs a bubble-point feed mode, where the molar compositions of E, P, and B are 0.333, 0.333, and 0.334 in sequence, with a total feed flow rate of 1 kmol/s. The three components are extracted from the column top, the side stream of the main column, and the column bottom, respectively, and all products must meet a purity requirement of 99 mol%.

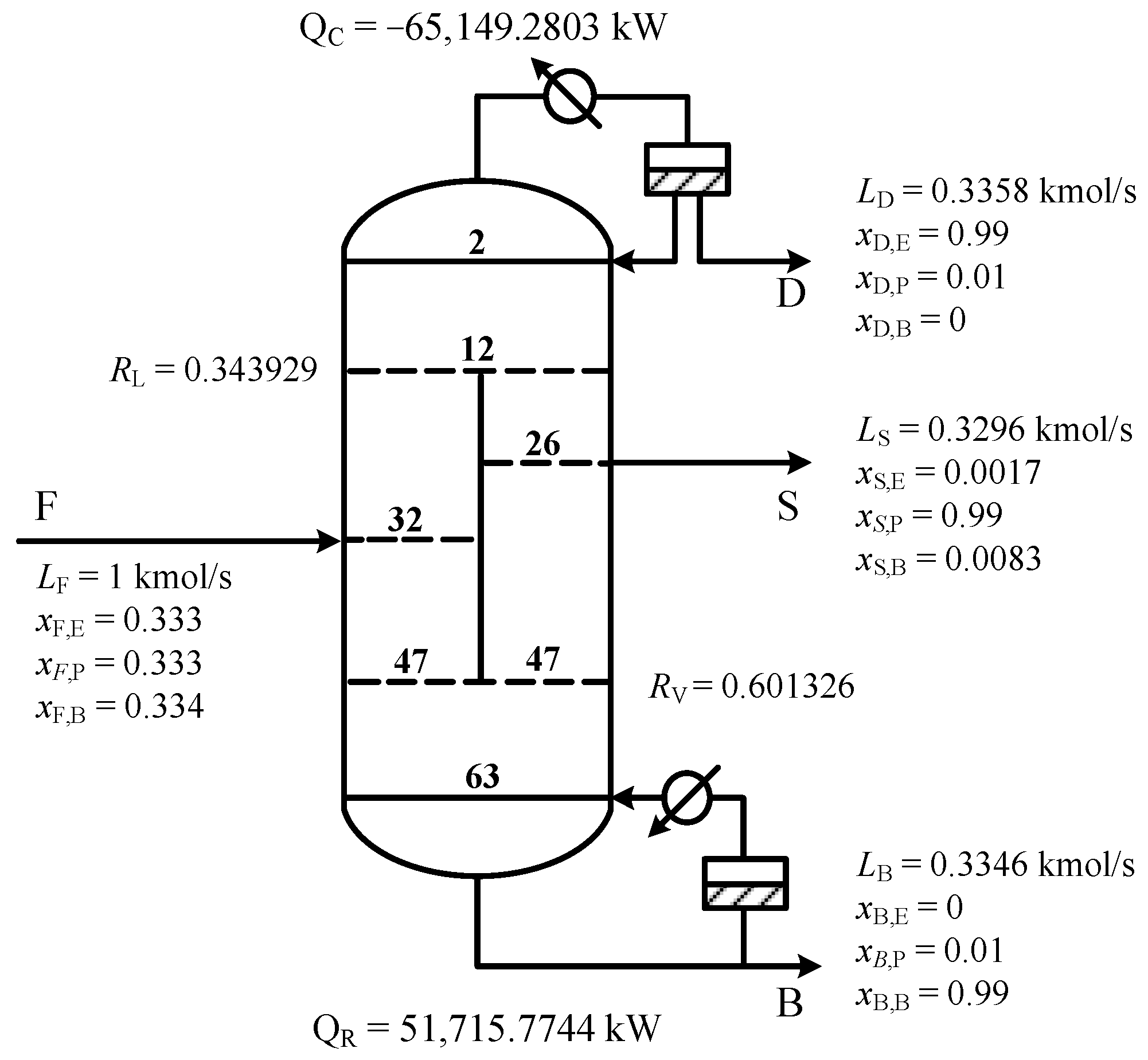

The separation process of this DWC is simulated using Aspen Plus V12 software. The UNIFAC thermodynamic model is employed to characterize the phase equilibrium of the EPB ternary system, and a four-column structure is adopted to construct the DWC model because Aspen Plus lacks a dedicated DWC module for direct modeling. In this study, the number of stages in the prefractionator and the main column section on both sides of the dividing wall is set to be the same. The optimization problem is solved using the classic grid search method, and the optimal design structure is shown in

Figure 2. The prefractionator contains 35 stages, while the main column contains 64 stages. The common rectifying section has 12 stages, and the common stripping section has 17 stages. The vapor split ratio (

) is 0.601326, and the liquid split ratio (

) is 0.343929. The condenser heat duty (

) is −65,149.2803 kW, and the reboiler heat duty (

) is 51,715.7744 kW. This steady-state design scheme is similar to the one in our previous study [

19]. The only difference is that a smaller step size is adopted for optimizing the two continuous variables,

and

, in this work, leading to more accurate optimization results than the previous scheme.

Subsequently, the steady-state DWC model established in Aspen Plus is further converted to a dynamic model in Aspen Dynamics. Prior to this conversion, critical preprocessing steps including tray sizing and pressure checks were completed in Aspen Plus following the standardized methodology outlined in Luyben’s authoritative work. For the dynamic model, a liquid holdup time of 5 min was specified for both the reflux drum and column bottom.

3.2. Conventional SOC Scheme for the EPB DWC

The basic control objective of EPB DWC is to ensure that the purities of the top, side stream, and bottom products meet their specifications. Except for the manipulated variables that must be used to maintain the feed flow rate, top column pressure, reflux drum level, and column bottom level, there are a total of four manipulated variables available in the EPB DWC for achieving this basic control objective, which are the distillate flow rate

, side stream product flow rate

,

, and

. To clarify the correlation between each manipulated variable and the stage temperatures, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Each of these four manipulated variables was varied by ±0.1%, respectively, and the analysis results are shown in

Figure 3. The results indicate that the sensitive stage corresponding to the

is stage 9 of the main column (

), the sensitive stage corresponding to the

is stage 38 of the main column (

), the sensitive stage corresponding to the

is stage 56 of the main column (

), and the sensitive stage corresponding to the

is stage 22 of the prefractionator (

).

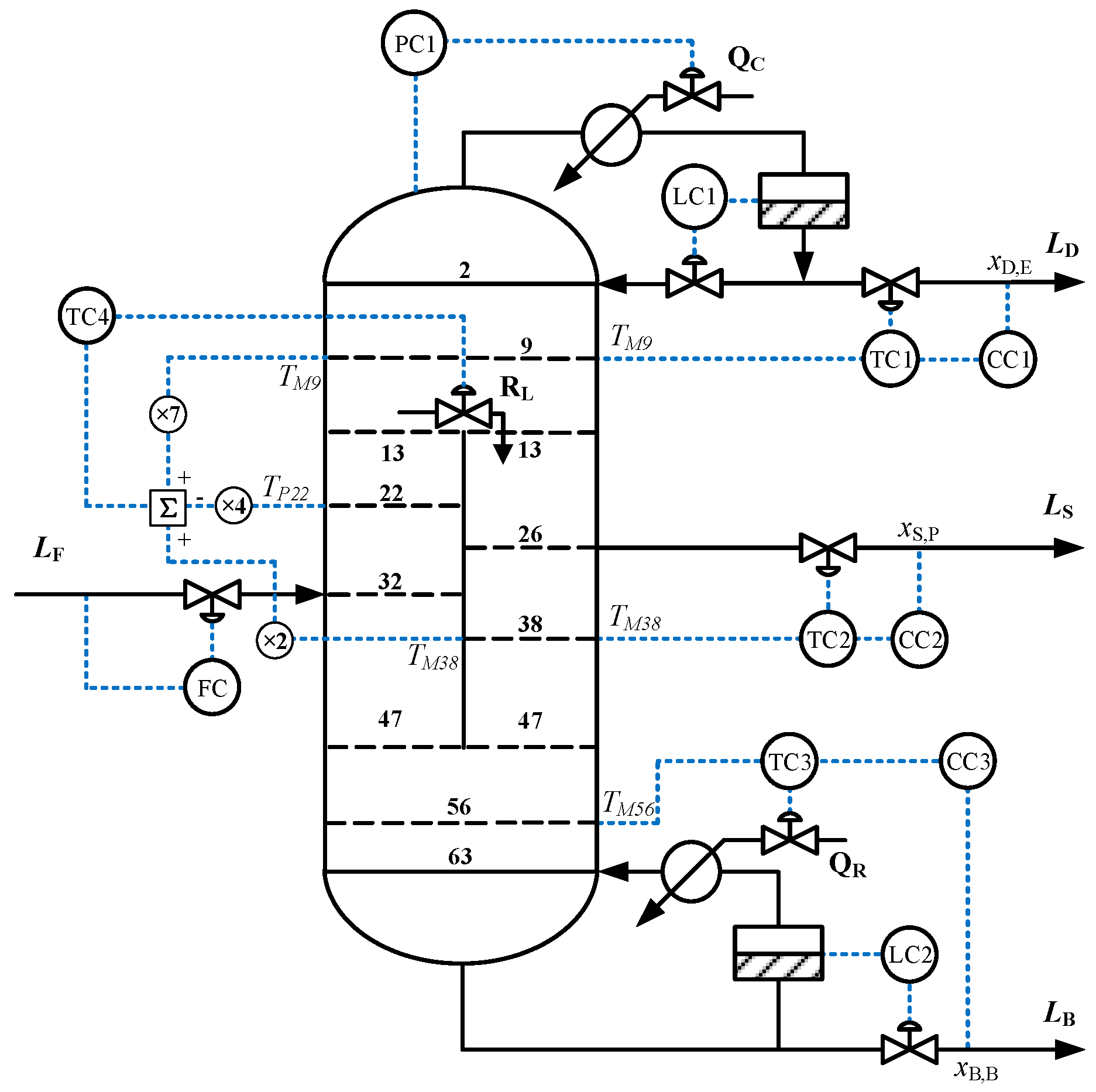

If the control objective focuses solely on maintaining the purities of three products of the EPB DWC, a concentration-temperature cascade control scheme can be easily derived by combining the aforementioned sensitivity analysis results. As shown in

Figure 4a, this control scheme is denoted CS-I. In this control scheme: The CC1-TC1 cascade control loop adjusts the

to influence

, thereby maintaining the purity of the top product (

); The CC2-TC2 cascade control loop adjusts the

to influence

, thereby maintaining the purity of the side stream product (

); The CC3-TC3 cascade control loop adjusts the

to influence

, thereby maintaining the purity of the bottom product (

). These three cascade control loops work synergistically to collectively achieve the control objective of maintaining the purities of the top, side stream, and bottom products in the DWC.

It should be noted that CS-I only utilizes three out of the four available manipulated variables. The remaining

still has regulatory potential and can be further used to construct a SOC loop, upgrading the system from basic control of only maintaining product purities to SOC. According to the research of Ling and Luyben [

20], strictly controlling the concentration of the heavy component at the top of the prefractionator can effectively prevent the heavy component from entering the main column through the top of the dividing wall, thereby maintaining the optimal operation of the DWC. Based on this, by introducing an additional temperature inferential control loop into CS-I, the

as the manipulated variable and the

as the controlled variable—a conventional SOC scheme can be formed, which is denoted as CS-II.

3.3. Deriving a SOC Scheme with the GP-Based Method for the EPB DWC

When designing a SOC loop using the GP-based method, the first task is to identify the core disturbance scenarios of concern. Considering that changes in feed composition are a key factor affecting the optimal operation of the system, and fully taking into account the nonlinear characteristics of the EPB DWC, this study selects three feed components with ±5% and ±10% fluctuations as disturbance conditions, setting a total of 12 disturbance scenarios, i.e., E+5% (the concentration of component E in the feed increases by 5%, while the ratio between the other components remains unchanged), E−5%, P+5%, P−5%, B+5%, B−5%, E+10%, E−10%, P+10%, P−10%, B+10%, B−10%. Under these 12 disturbance scenarios, with the constraint that the purity of the three products is maintained at 99%, the optimal operating point for each scenario is determined by adjusting the

, and the specific results are shown in

Table 1. Meanwhile, the temperature profile in the column under each optimal operating scenario is recorded to provide a basis for subsequent fitness value calculation.

Employing the GP-based method to search for the SOCV for the , the terminal set is set to the sensitive stage temperatures corresponding to the , , , and , i.e., , , , and . Compared with the conventional SOC scheme CS-II, this setup does not require additional sensors, thus having stronger engineering practicability. The function set only includes the three arithmetic operations, i.e., addition, subtraction, and multiplication, to cover common linear and simple nonlinear combination forms in SOCV design, and division is excluded to avoid numerical instability caused by small denominators. The algorithm parameters are configured as follows: population size of 60, maximum number of evolutionary generations of 50, crossover rate of 0.6, and node mutation rate of 0.1. This parameter combination is determined through multiple rounds of independent optimization runs, aiming to balance search efficiency and solution diversity, ensuring that the algorithm can effectively explore the entire solution space and avoid falling into local optima.

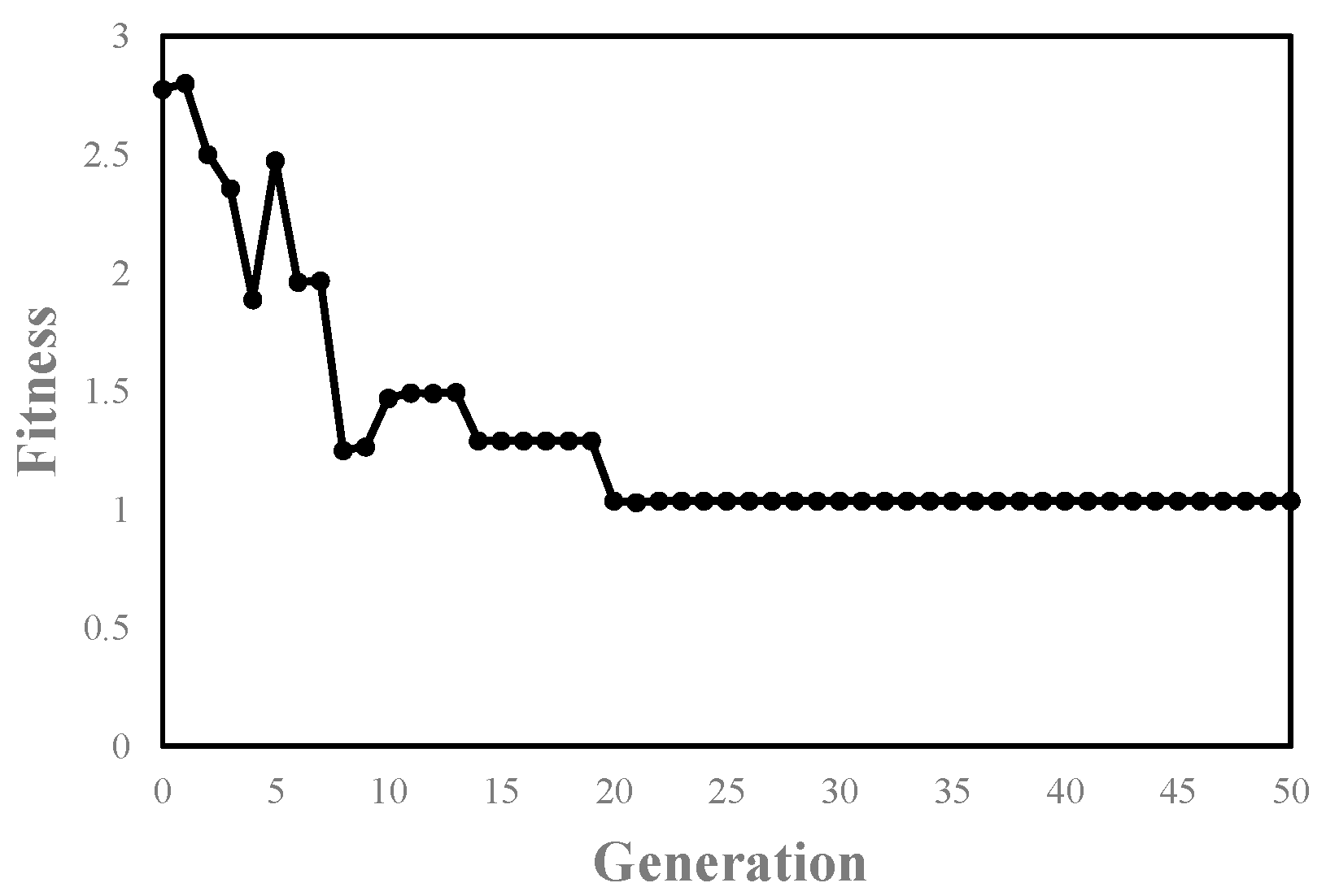

The optimization process is shown in

Figure 5, where the vertical axis represents the minimum fitness value in each generation of the population. It can be seen that the evolutionary process tends to converge after about 20 generations. Finally, the SOCV expression corresponding to the

is obtained as

. The SOC scheme derived based on this result is shown in

Figure 6, denoted CS-III. The most prominent difference between CS-III and CS-II is that the controlled variable of the TC4 control loop is replaced from

with the combination of sensitive stage temperatures (

) obtained via the GP-based SOCV selection method, while all other control loops remain unchanged.

3.4. Comparisons of the Conventional SOC Schemes and the SOC Scheme Derived by the GP-Based Method for the EPB DWC

To fully evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed GP-based SOC design method, this study compares the control performance of the derived CS-III with that of CS-I and CS-II. For the fairness of comparison, the same control system settings were adopted in these three control schemes. All control loops adopt PI controllers; the dead time of temperature measurements is set to 1 min, and that of concentration measurements is set to 3 min. The controller parameter tuning is performed using the Tyreus-Luyben rule [

21]. The specific tuning results are summarized in

Table 2.

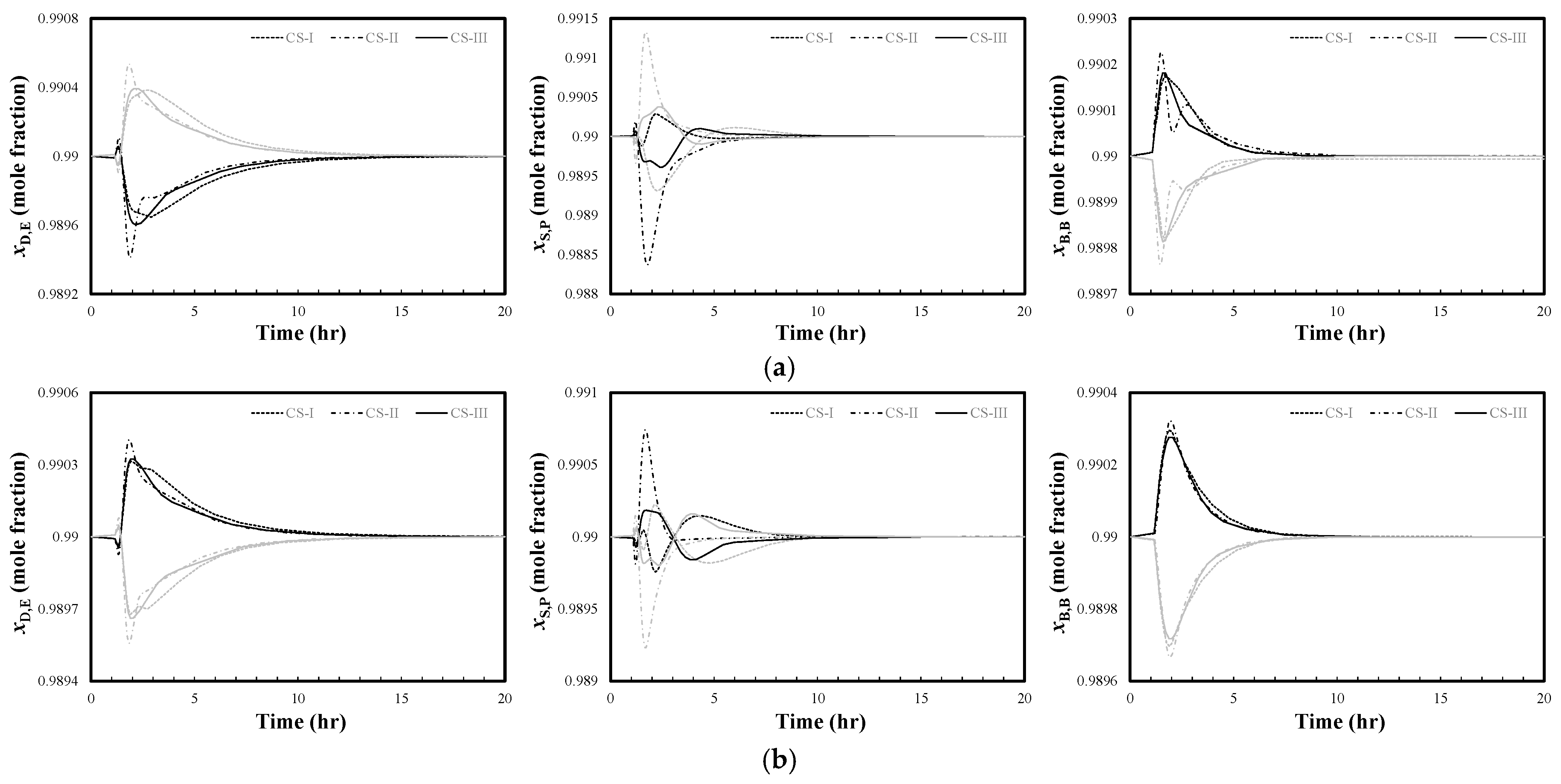

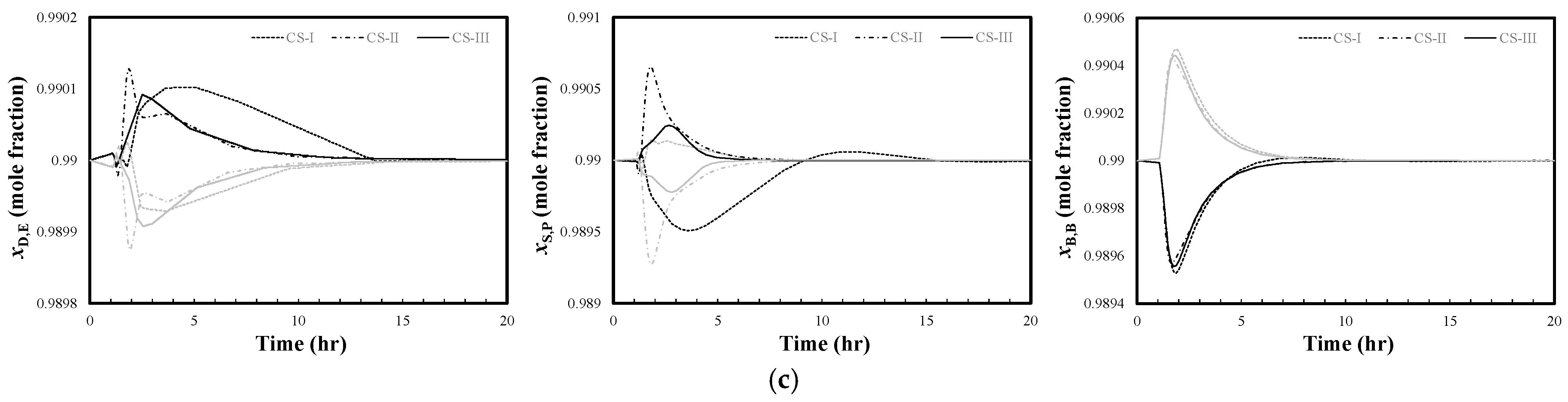

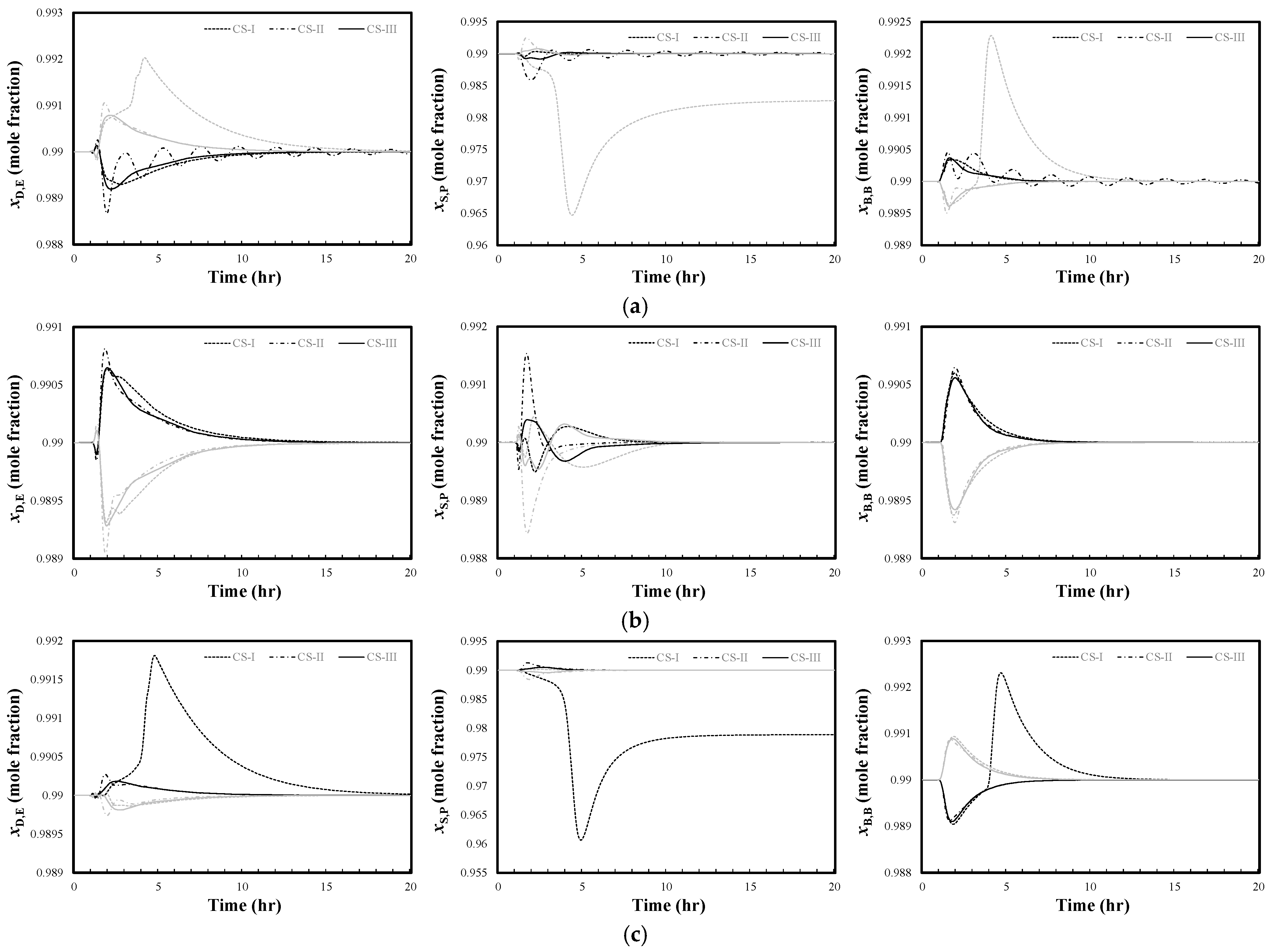

To analyze the closed-loop control performance under feed composition disturbances,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the closed-loop response characteristics of the EPB DWC system after the feed components E, P, and B are subjected to ±5% and ±10% step disturbances, respectively. The black line denotes positive disturbance, and the gray line denotes negative disturbance. As can be seen from the figures, except the fact that the purity of side stream product

in CS-I fails to return to the setpoint when encountering E−10% and B+10% disturbances, the product purities of the three control schemes in other disturbances can recover to stability within a certain period. Compared with CS-I and CS-II, CS-III exhibits a faster response speed, with the shortest settling time and the smallest overshoot. The dynamic performance of the system is significantly improved, which fully verifies the superiority and effectiveness of the proposed GP-based SOC scheme in coping with various disturbances.

Table 3 lists the steady-state value of

of the EPB DWC with CS-I, CS-II and CS-III after the feed components E, P, and B are subjected to ±5% and ±10% step disturbances, respectively. The data show that when the feed components are disturbed by ±5%, the average

of CS-III and CS-II are reduced by 92.2217 kW and 28.5720 kW as compared to CS-I, respectively. When the disturbance amplitude increases to ±10%, the average

of CS-III and CS-II are reduced by 3256.8018 kW and 2928.5473 kW as compared to CS-I, respectively. This indicates that CS-III has obvious advantages over CS-I and CS-II in energy consumption control, and the energy-saving effect becomes more significant with the increase in disturbance amplitude. The results further confirm the excellent energy-saving performance of the proposed GP-based SOC scheme under different disturbance conditions. It can not only effectively reduce system energy consumption but also improve system robustness, ensuring that the system maintains efficient and stable operation even under large-amplitude disturbances.

The effectiveness of the method is fully verified in the EPB DWC case study. Under 12 feed composition disturbance scenarios, the derived SOC scheme (CS-III) stably maintains the product purity at 99 mol%. It exhibits faster response speed, shorter settling time, and smaller overshoot as compared to CS-I and CS-II, which significantly improves system robustness against external disturbances. More importantly, the GP-derived SOCV enables substantial energy savings: compared to CS-I, the average of CS-III is reduced by 92.2217 kW under ±5% disturbances and by 3256.8018 kW under ±10% disturbances. Notably, the energy-saving effect becomes more pronounced with increasing disturbance amplitude, aligning perfectly with industrial demands for energy conservation under complex operating conditions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of the Proposed GP-Based SOC Design Method

The proposed GP-based SOC design method demonstrates remarkable effectiveness in addressing the core challenge of SOCV selection and optimizing the control performance of complex separation processes, as validated by both theoretical innovations and practical case study results. Theoretically, it overcomes the inherent limitations of conventional SOCV selection methods. Compared with mechanism analysis-based approaches, the proposed GP-based method does not rely heavily on professional expertise, as it enables data-driven autonomous evolution of SOCVs. By taking candidate controlled variables as the terminal set and basic arithmetic operations as the function set, the algorithm performs iterative optimization through selection, crossover, and mutation to generate an optimal composite SOCV. This SOCV inherently maintains a strong correlation with the system’s optimal operating state, which significantly reduces human subjectivity and enhances the scientific rigor of SOC scheme design. In contrast to conventional numerical analysis-based methods, the GP-based approach provides an effective means of constructing SOCVs by combining usable controlled variables, rather than generating well pairs of controlled variables and manipulated variables.

Additionally, the GP-based method offers exceptional flexibility in engineering applications, particularly for retrofitting existing plants. It can synthesize feasible SOC schemes based on the sensor configuration of current installations to construct optimal SOCVs. This eliminates the need for additional sensor installation or major hardware modifications, significantly reducing the cost and complexity of applying SOC technology to old plants. This flexibility enhances the engineering practicability and promotion potential of the proposed method.

4.2. Limitations of the Proposed GP-Based SOC Design Method

Two primary limitations of the proposed GP-based SOC design method should be acknowledged. First, as an evolutionary algorithm by nature, the method exhibits inherent randomness in its optimization results, which are influenced by key hyperparameters including population size, mutation rate, and number of generations; although multiple independent optimization runs have been employed to ensure robustness, slight fluctuations in the optimal solution may still occur under different initial parameter settings. Second, the method cannot be completely decoupled from its dependence on the process model of the controlled unit: specifically, searching for optimal SOCVs requires obtaining temperature profile data of the controlled unit under various disturbance scenarios, and this data relies on prior modeling of the controlled object (steady-state simulation), meaning the method’s applicability and accuracy are partially constrained by the fidelity of the established process model.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a GP-based method to derive SOC schemes for complex distillation processes, aiming to solve the core problem of scientific SOCV selection in SOC design, and validates it using an EPB DWC as a case study. The results show that the method, by defining a terminal set of sensitive stage temperatures, a function set of basic arithmetic operations, and a fitness function reflecting the SOCV’s tracking ability to the optimal operating point, enables the GP algorithm to autonomously evolve an optimal linear SOCV without manual intervention, effectively overcoming the subjectivity and limitations of traditional SOCV selection methods. The derived SOC scheme, combined with three concentration-temperature cascade control loops for product purity maintenance, exhibits excellent control performance while achieving significant energy savings that become more pronounced with increasing disturbance amplitude. Moreover, the method utilizes existing process variables without additional sensors, ensuring strong engineering practicability. In conclusion, the GP-based SOC design method provides a scientific and efficient solution for energy-saving optimization control of DWC and similar complex distillation processes, enriching the theoretical system of SOC by proposing a data-driven SOCV selection method, which expands the algorithmic framework for SOC scheme design. Future research will explore adaptive GP parameters to mitigate randomness and local optima and extend the fitness function to product purity fluctuation and environmental impact for multi-objective SOC optimization.