Bioproduction of Gastrodin from Lignin-Based p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde Through the Biocatalysis by Coupling Glycosyltransferase UGTBL1-Δ60 and Carbonyl Reductase KPADH

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cultivation of Microbial Strains

2.3. Glycosylation of p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde

2.4. Construction of the Reduction System

2.5. Homologous Modeling and Molecular Docking Analysis

2.6. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

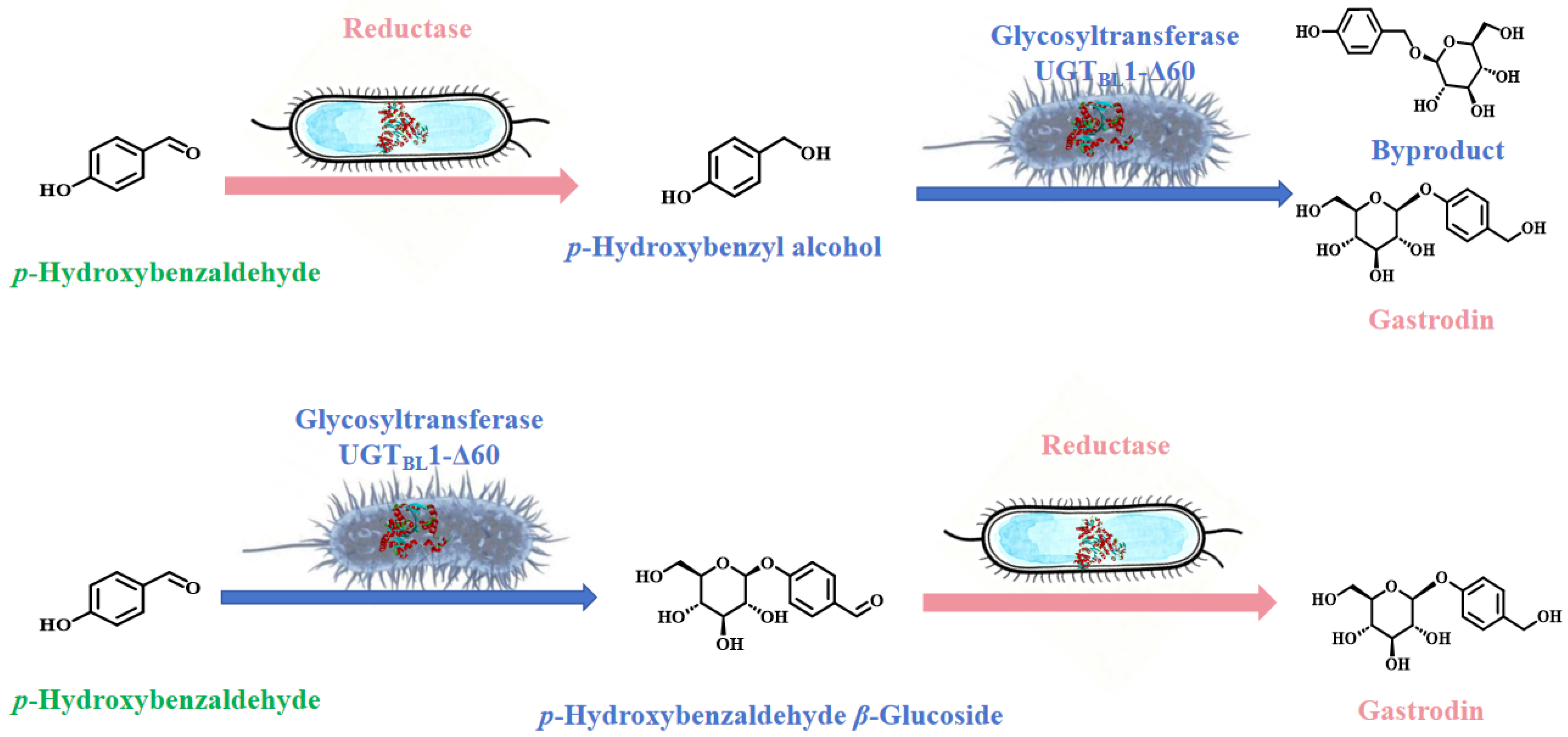

3.1. Screening of Reductase

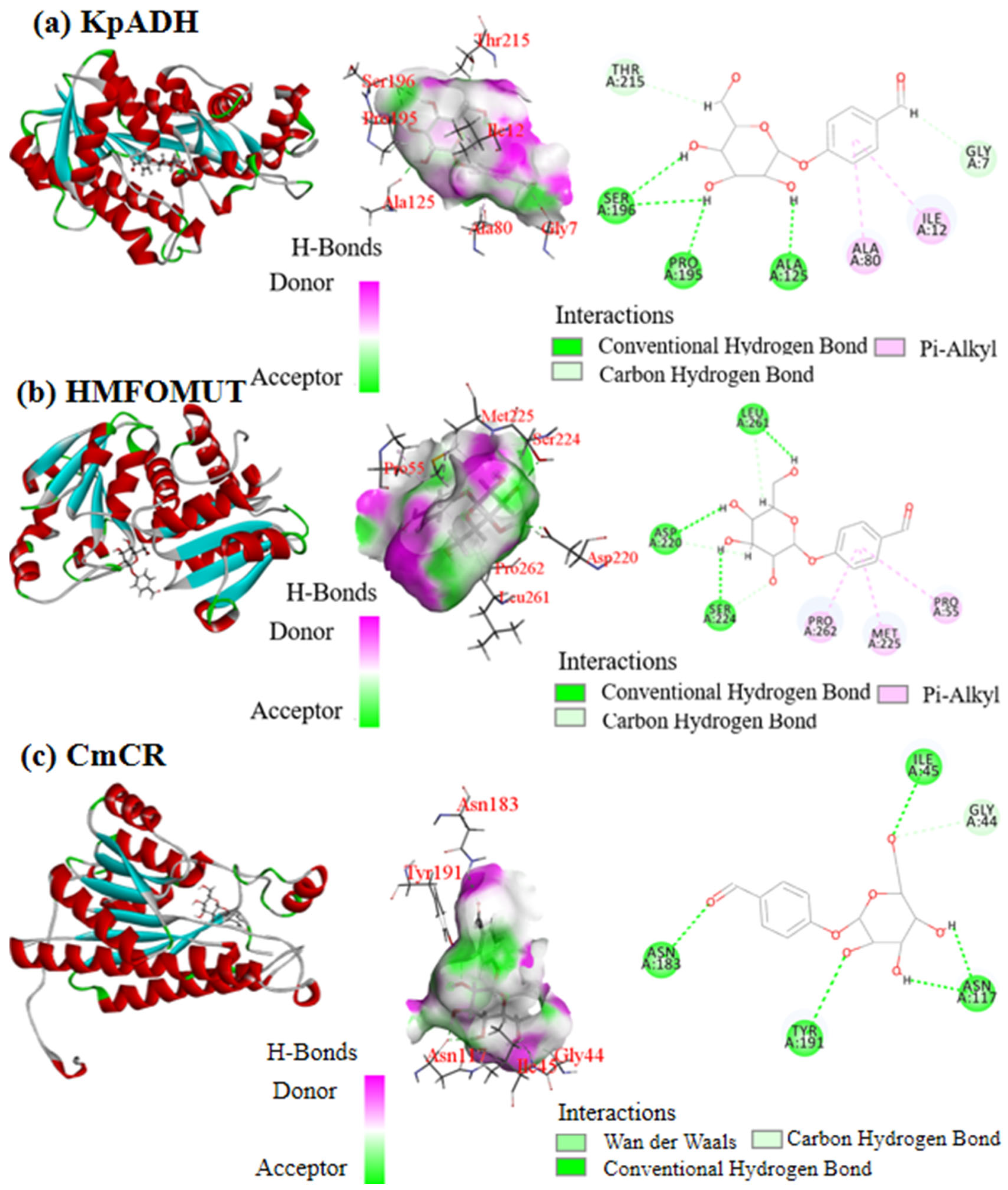

3.2. Results of Molecular Docking of Different Enzymes with p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde β-Glucoside

3.3. Optimization of Reduction Reaction Conditions

3.4. The Impact of Bacterial Reuse on Gastrodin Yield

3.5. The Reaction Process Curve of the Synthesis of Gastrodin Catalyzed by KpADH

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, T.; Zhou, T.; Li, C.; Song, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H. Development status and prospects of biomass energy in China. Energies 2024, 17, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikovhi, A.; Motaung, T.E. Technologies and innovations for biomass energy production. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, D.; Qin, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, X. High value-added monomer chemicals and functional bio-based materials derived from polymeric components of lignocellulose by organosolv fractionation. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2020, 14, 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, W.-Y.; Hur, H.-G.; Kim, T.-Y.; Ghatge, S. Thermoalkaliphilic laccase treatment for enhanced production of high-value benzaldehyde chemicals from lignin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.J.; Vallejos, M.E.; Area, M.C.; Felissia, F.E. Kinetics of vanillin and vanillic acid production from pine Kraft lignin. Processes 2024, 12, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penín, L.; Gigli, M.; Sabuzi, F.; Santos, V.; Galloni, P.; Conte, V.; Parajó, J.C.; Lange, H.; Crestini, C. Biomimetic vanadate and molybdate systems for oxidative upgrading of iono- and organosolv hard- and softwood lignins. Processes 2020, 8, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y. From vanillin to biobased aromatic polymers. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 4255–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, T.; Becker, A.; Terholsen, H.; Kim, I.J.; Menyes, I.; Buchwald, S.; Balke, K.; Santala, S.; Almo, S.C.; Bornscheuer, U.T. LuxAB-based microbial cell factories for the sensing, manufacturing and transformation of industrial aldehydes. Catalysts 2021, 11, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.D.F.; Lautru, S.; Pernodet, J.-L. Genetic engineering approaches for the microbial production of vanillin. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nasr, I.S.; Koko, W.S.; Khan, T.A.; Schobert, R.; Biersack, B. Antiparasitic activities of acyl hydrazones from cinnamaldehydes and structurally related fragrances. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ma, C.; Chai, H.; He, Y.-C. Biological valorization of lignin-derived vanillin to vanillylamine by recombinant E. coli expressing ω-transaminase and alanine dehydrogenase in a petroleum ether-water system. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 385, 129453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Fu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, W.; He, Y. Efficient bioproduction of p-hydroxybenzaldehyde β-glucoside from p-hydroxybenzaldehyde by glycosyltransferase mutant UGTBL1-Δ60. Biology 2025, 14, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Fu, X.; Wang, P.; Li, K.; Wei, L.; Zhai, S.; An, Q. Selective production of p-hydroxybenzaldehyde in the oxidative depolymerization of alkali lignin catalyzed by copper-containing imidazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 385, 122378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, G.; Cai, M.; Liu, R.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Tan, Q.; Hai, C. Gastrodin alleviates cerebral ischemic damage in mice by improving anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation activities and inhibiting apoptosis pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yang, G.-Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Z.; Feng, Y. Biosynthesis of plant-derived ginsenoside Rh2 in yeast via repurposing a key promiscuous microbial enzyme. Metab. Eng. 2017, 42, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-B.; Guo, Q.-L.; Wang, Y.-N.; Lin, S.; Zhu, C.-G.; Shi, J.-G. Gastrodin derivatives from Gastrodia elata. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2019, 9, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, M.; Wang, X.; Peng, Z.; Cai, C.; Xi, J.; Yan, C.; Luo, J.; Li, X. Gastrodin: A comprehensive pharmacological review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg′s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 3781–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Tang, R.; Yang, N.; Chen, Y. Review on pharmacological effects of gastrodin. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2023, 46, 744–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Lv, J.; Liao, X. Study on the uptake of Gastrodin in the liver. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yan, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, W.; Yu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.; Ding, A.; Shan, M. Optimal extraction study of Gastrodin-type components from Gastrodia elata tubers by response surface design with integrated phytochemical and bioactivity evaluation. Molecules 2019, 24, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassanini, I.; Kapešová, J.; Petrásková, L.; Pelantová, H.; Markošová, K.; Rebroš, M.; Valentová, K.; Kotik, M.; Káňová, K.; Bojarová, P.; et al. Glycosidase-catalyzed synthesis of glycosyl esters and phenolic glycosides of aromatic acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-W.; Ma, C.-L. Improved synthesis of gastrodin, a bioactive component of a traditional Chinese medicine. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2014, 79, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Sha, X.; Qiao, G.; Niu, F.; Ming, H.; Cui, C. Biosynthesis of gastrodin via multi-module UDPG supply and site-directed mutagensis of glycosyltransferase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Catal. 2025, 578, 114953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, J.; Jiang, K.; Xue, F. A Glycosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana enables the efficient enzymatic synthesis of Gastrodin. Catal. Lett. 2024, 154, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Xu, W.; Jia, R.; Xia, Y. Recombinant expression and characterization of an alkali-tolerant UDP-glycosyltransferase from Solanum lycopersicum and its biosynthesis of Gastrodin. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2410029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, N.; Zhou, H.; Su, Y.; Du, S.; Hussain, A.; Xia, X. Directed evolution of the UDP-glycosyltransferase UGTBL1 for highly regioselective and efficient biosynthesis of natural phenolic glycosides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Hu, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, T. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for high-level production of gastrodin from glucose. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Dong, W.; Chen, T.; Chu, J.; He, B. Switching glycosyltransferase UGTBL1 regioselectivity toward polydatin synthesis using a semi-rational design. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Lin, R.; Gu, X.; Cui, R.; Yang, R.; He, Y.-C. Synthesis of biobased alcohols from biomass-derived aldehydes through the biocatalysis with E. coli KPADH in deep eutectic solvent ChCl:Glycerol-water. Mol. Catal. 2025, 584, 115305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Wu, L.; Han, R.; Schwaneberg, U.; Rao, Y.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Zhou, J.; Ni, Y. Structural insight into enantioselective inversion of an alcohol dehydrogenase reveals a “Polar Gate” in stereorecognition of diaryl ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12645–12654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.-C.; Tao, Z.-C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.-X.; Xu, J.-H. Highly efficient synthesis of ethyl (S)-4-chloro-3-hydroxybutanoate and its derivatives by a robust NADH-dependent reductase from E. coli CCZU-K14. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 161, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Gong, C.-J.; He, Y.-C. Improved biosynthesis of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid and furoic acid from biomass-derived furans with high substrate tolerance of recombinant Escherichia coli HMFOMUT whole-cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madavi, T.B.; Chauhan, S.; Keshri, A.; Alavilli, H.; Choi, K.-Y.; Pamidimarri, S.D.V.N. Whole-cell biocatalysis: Advancements toward the biosynthesis of fuels. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2022, 16, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, L.-X.; Chen, W.; Zhong, J.-J.; Qian, C.; Zhou, W.-W. Rational design of daunorubicin C-14 hydroxylase based on the understanding of its substrate-binding mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Teng, Z.; Rao, Z. Combinatorial protein engineering and transporter engineering for efficient synthesis of L-Carnosine in Escherichia coli. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 387, 129628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoben, C.V.; Ghazy, E.; Zeyen, P.; Darwish, S.; Schmidt, M.; Romier, C.; Robaa, D.; Sippl, W. Binding free energy (BFE) calculations and quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) analysis of Schistosoma mansoni histone deacetylase 8 (smHDAC8) inhibitors. Molecules 2021, 26, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Bu, C.; Huang, X.; Ouyang, J. Efficient whole-cell biotransformation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae NL22. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 3825–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-Y.; Zhang, R.-X.; Zheng, X.-F.; Zhao, Z.-P.; Sang, L. Highly-efficient synthesis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose in micropacked bed reactors: Multiphase transport, reaction optimization, and heterogeneous kinetic study. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcus, V.L.; Mulholland, A.J. Temperature, dynamics, and enzyme-catalyzed reaction rates. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2020, 49, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.F.; Ju, L.-K. On optimization of enzymatic processes: Temperature effects on activity and long-term deactivation kinetics. Process Biochem. 2023, 130, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M.J.; Barwell, S.A.E.; Holyoak, T.; Thorne, R.E. A structural perspective on the temperature dependent activity of enzymes. Structure 2025, 33, 924–934.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-X.; Li, X.-F.; Zhao, G.-L. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals the effect mechanisms of glucose on the biomass and phenolic glycoside esters synthesis activity of Candida parapsilosis ACCC 20221 whole-cell catalyst. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 20140–20152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, Y.-C.; Ma, C. Transformation of D-xylose into furfuryl alcohol via an efficient chemobiological approach in a benign deep eutectic solvent lactic acid:betaine-water reaction system. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 410, 125576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marquina, G.; Langer, J.; Sánchez-Costa, M.; Jiménez-Osés, G.; López-Gallego, F. Immobilization and stabilization of an engineered acyltransferase for the continuous biosynthesis of Simvastatin in packed-bed reactors. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 9899–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Oku, Y.; Matsuda, T. Application of immobilized enzymes in flow biocatalysis for efficient synthesis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2024, 28, 1308–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Hong, X.; Abdullah; Yao, R.; Xiao, Y. Rapid biosynthesis of phenolic glycosides and their derivatives from biomass-derived hydroxycinnamates. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Z. Gastrodin reduces Aβ brain levels in an Alzheimer′s disease mouse model by inhibiting P-glycoprotein ubiquitination. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Han, Z.; Bao, W.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y. Gastrodin attenuates cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury by enhancing mitochondrial fusion and activating the AMPK-OPA1 signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, B.; Guo, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, A. Enhancing Gastrodin production in Yarrowia lipolytica by metabolic engineering. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tegl, G.; Nidetzky, B. Glycosyltransferase co-immobilization for natural product glycosylation: Cascade biosynthesis of the C-glucoside nothofagin with efficient reuse of enzymes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 2157–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteria | Substrate Structure | Product Structure | CDOCKER_Energy, kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|

| KpADH (Recombinant E. coli KpADH) |  |  | −11.99 |

| HMFOMUT (Recombinant E. coli HMFOMUT) | −6.77 | ||

| CmCR (Recombinant E. coli CCZU-K14) | −8.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, B.; Xiong, J.; Ma, C.; He, Y.-C. Bioproduction of Gastrodin from Lignin-Based p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde Through the Biocatalysis by Coupling Glycosyltransferase UGTBL1-Δ60 and Carbonyl Reductase KPADH. Processes 2026, 14, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010055

Fan B, Xiong J, Ma C, He Y-C. Bioproduction of Gastrodin from Lignin-Based p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde Through the Biocatalysis by Coupling Glycosyltransferase UGTBL1-Δ60 and Carbonyl Reductase KPADH. Processes. 2026; 14(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Bao, Jiale Xiong, Cuiluan Ma, and Yu-Cai He. 2026. "Bioproduction of Gastrodin from Lignin-Based p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde Through the Biocatalysis by Coupling Glycosyltransferase UGTBL1-Δ60 and Carbonyl Reductase KPADH" Processes 14, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010055

APA StyleFan, B., Xiong, J., Ma, C., & He, Y.-C. (2026). Bioproduction of Gastrodin from Lignin-Based p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde Through the Biocatalysis by Coupling Glycosyltransferase UGTBL1-Δ60 and Carbonyl Reductase KPADH. Processes, 14(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010055