Integrated Electrochemical–Electrolytic Conversion of Oilfield-Produced Water into Hydrogen

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental System

2.1. Produced Water Purification System

2.2. Hydrogen Production System

3. Laboratory Instruments and Water Quality Testing

3.1. Experimental Apparatus and Methods

3.2. Wastewater Quality Testing

3.3. Produced Water Purification Unit

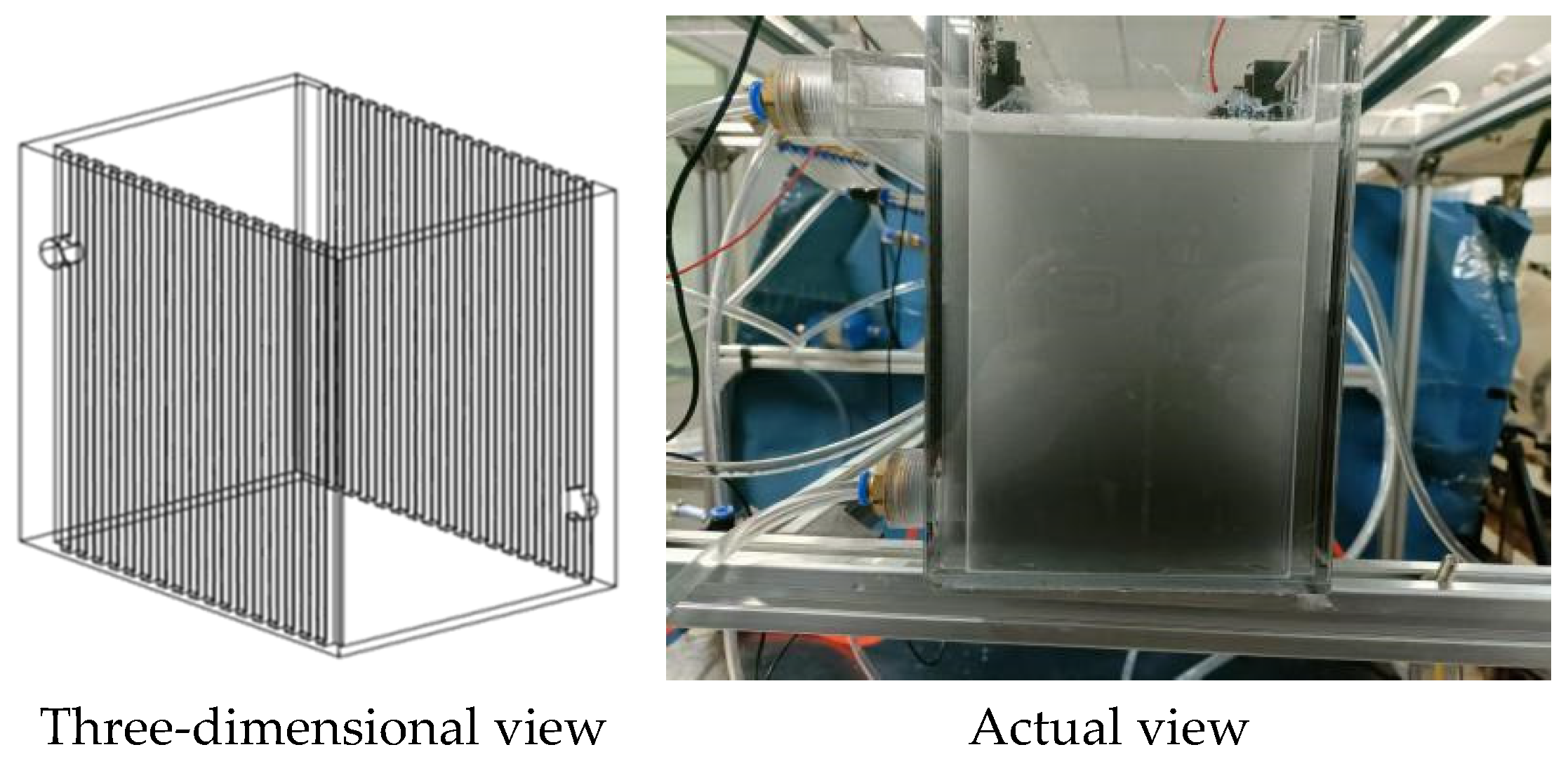

3.3.1. Structural Design of the ED Reaction Zone

3.3.2. Structural Design of the EC Reaction Zone

3.3.3. Structural Design of the EF Reaction Zone

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Water Quality Analysis of Produced Water Treatment

4.2. Optimal Conditions for Hydrogen Production from Produced Water

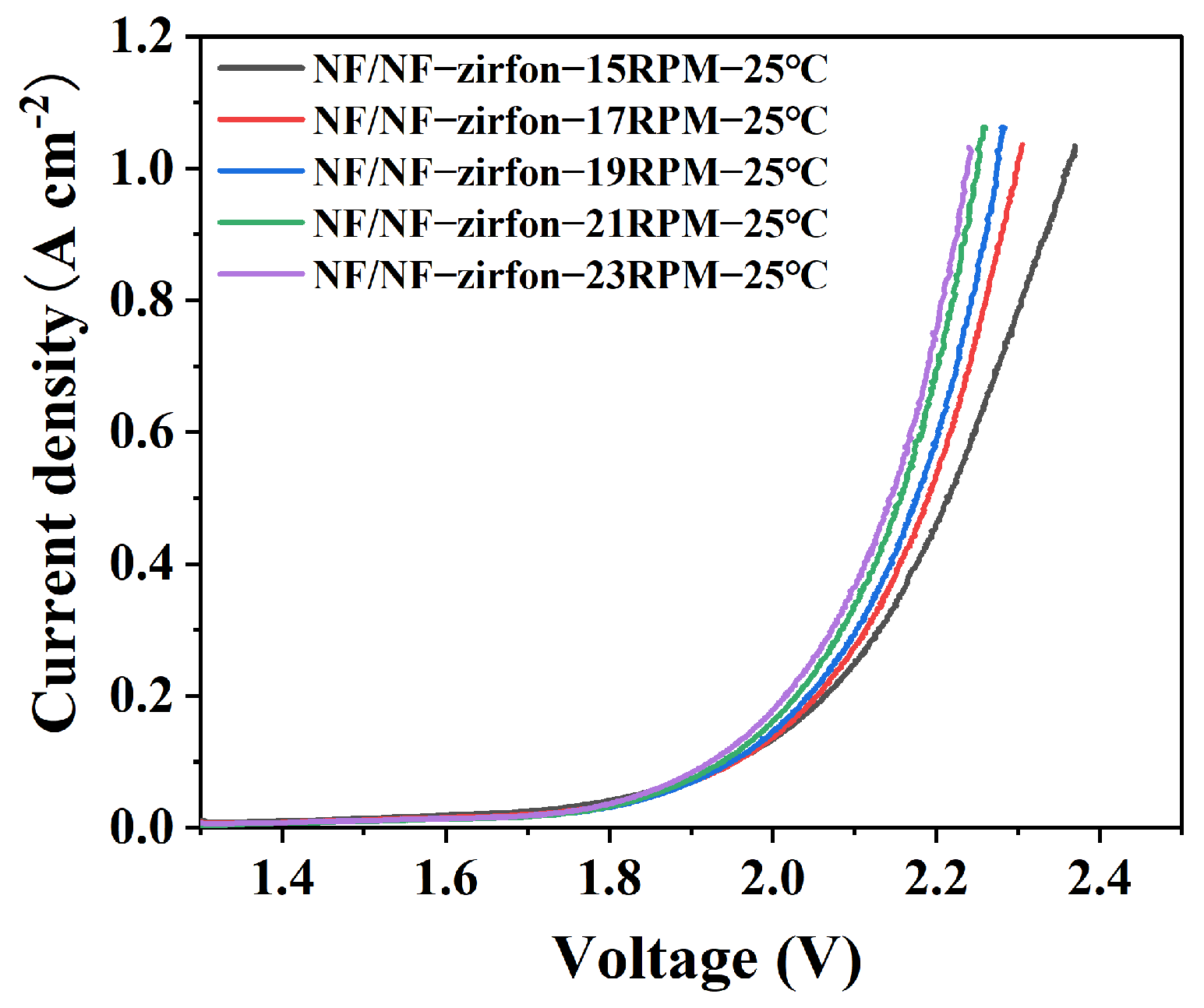

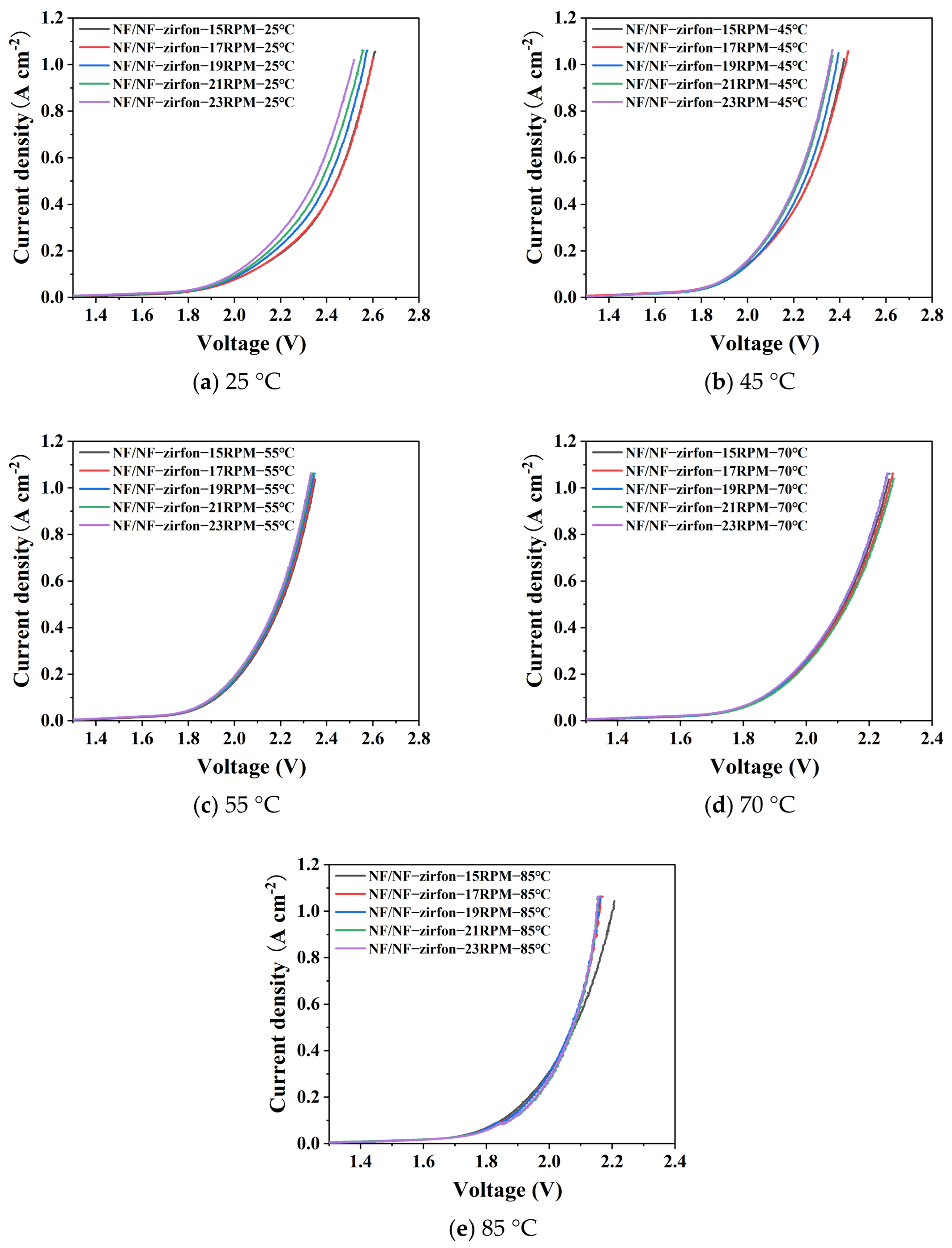

4.2.1. Temperature and Flow Rate Influence Patterns

4.2.2. Patterns Influencing Catalyst Performance

- (1)

- Upon replacing the conventional nickel mesh with a nickel–aluminum alloy as the cathode catalyst, the cell voltage decreased significantly from 2.15 V to 2.342 V at a current density of 1 A cm−2 (85 °C), while hydrogen purity increased from 87.12% to 95.13%. Notably, synergistic effects emerged between elevated temperature and increased flow velocity: when the temperature rose from 55 °C to 85 °C, cell voltage decreased by 0.051 V. Concurrently, heightened flow velocity enhanced mass transfer, thereby boosting current density and reducing energy consumption.

- (2)

- The discovery of an altered anode catalyst reveals that three-dimensional porous nickel fiber felt, owing to its abundant active sites and excellent conductivity, requires only 1.952 V to sustain 1 A cm−2 under conditions of 85 °C and 23 RPM (1 L/min). This represents a 13% reduction in cell potential compared to nickel mesh anodes, while simultaneously enhancing hydrogen purity to 96.45%.

- (3)

- The optimal process parameters are as follows: employing a nickel fiber felt anode and a nickel–aluminum alloy cathode, operating at 85 °C and 23 RPM (1 L/min), achieving efficient hydrogen production with a cell voltage of 1.952 V and a current density of 1 A cm−2, while hydrogen purity exceeds 96%.

4.2.3. Patterns of Electrolyte Concentration Influence

- (1)

- As shown in Figure 13a–c, the electrolysis temperature exhibits a significant negative correlation with system energy consumption. When the operating temperature is raised from ambient to 85 °C, the energy consumption per unit of hydrogen produced decreases monotonically, while the hydrogen purity increases to 96.48%. This indicates that elevated temperatures effectively promote the electrolytic reaction kinetics.

- (2)

- As shown in Figure 13d–f, within the 3M KOH electrolyte system, the regulatory effect of flow rate on system energy consumption diminishes. This is primarily attributable to the high electrolyte concentration (3M) ensuring sufficient OH− ion transport flux, thereby shifting the electrode reaction process from mass transfer control to charge transfer control. Consequently, the influence of rotational speed parameters on performance is significantly reduced. The optimal operating conditions are 85 °C and 23 rpm (1.0 L/min). Under these conditions, hydrogen production using 3M KOH electrolyte reduces the cell potential from 2.15 V to 1.896 V compared to 1M electrolyte, achieving a 12% reduction in energy consumption.

- (3)

- As shown in Figure 13g–i, the optimum operating conditions are 85 °C and 21 rpm. Under these conditions, hydrogen production using 6M KOH reduces the cell potential from 2.15 V to 1.856 V compared to 1M electrolyte, achieving a 13% reduction in energy consumption.

- (4)

- The optimum process parameters are as follows: employing a nickel fiber felt anode and a nickel–aluminum alloy cathode, operating at 85 °C, 21 RPM (0.8 L/min), 6 M KOH, and a current density of 1 A cm−2, yielding hydrogen purity of 96.58%.

4.3. Water Quality Specifications for Hydrogen Production from Produced Water

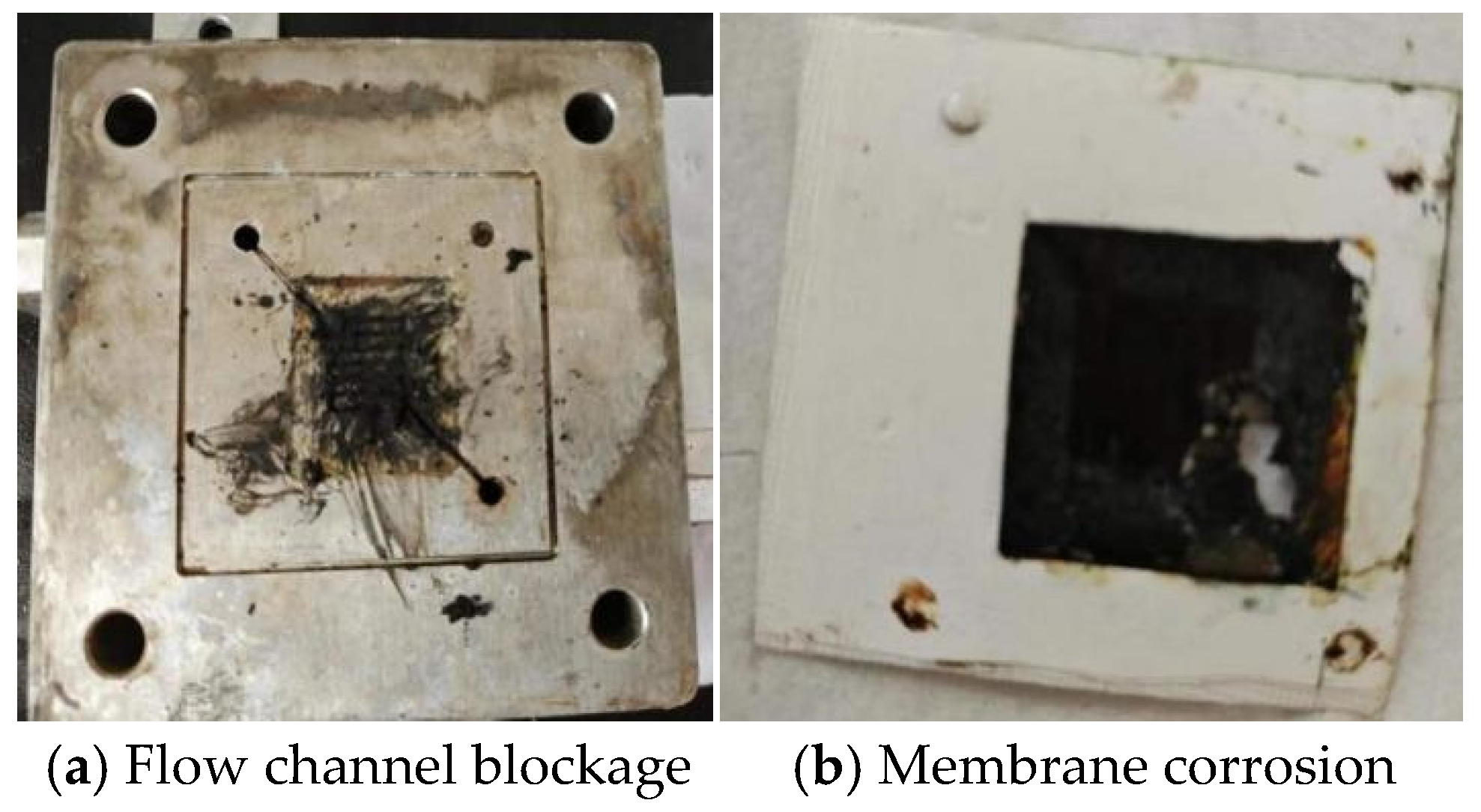

4.3.1. Problems Encountered in the Reaction

- (1)

- Excessively high oil content in produced water leads to the formation of black granular deposits.

- (2)

- Excessively high chloride ion content in produced water leads to corrosion of the electrolytic membrane.

4.3.2. Solutions

- (1)

- EC process for removing high crude oil content from produced water.

- (2)

- Process improvements for chloride ion suppression.

- (3)

- Replace the material of the electrolytic cell.

4.3.3. Determination of Hydrogen Production Parameters

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- For the complex produced water from the Changqing Oilfield (suspended solids > 1600 mg/L, turbidity > 350 NTU, oil content 90–120 mg/L), a multi-stage EDCF purification process was developed. After treatment, the oil content was reduced to 6.083 mg/L (removal rate 95%), suspended solids to below 20 mg/L (removal rate 98%), and turbidity to below 20 NTU (removal rate 94%). This provides stable feedwater conditions for subsequent electrolytic hydrogen production.

- (2)

- Through synergistic optimization of electrochemical kinetics and mass transfer, the optimal hydrogen production performance was achieved using a nickel fiber felt anode and a nickel–aluminum alloy cathode under the following conditions: temperature 85 °C, flow rate 21 revolutions per minute (0.8 L/min), electrolyte concentration 6 M KOH, and current density 1 A/cm2. The hydrogen purity attained was 96.58%.

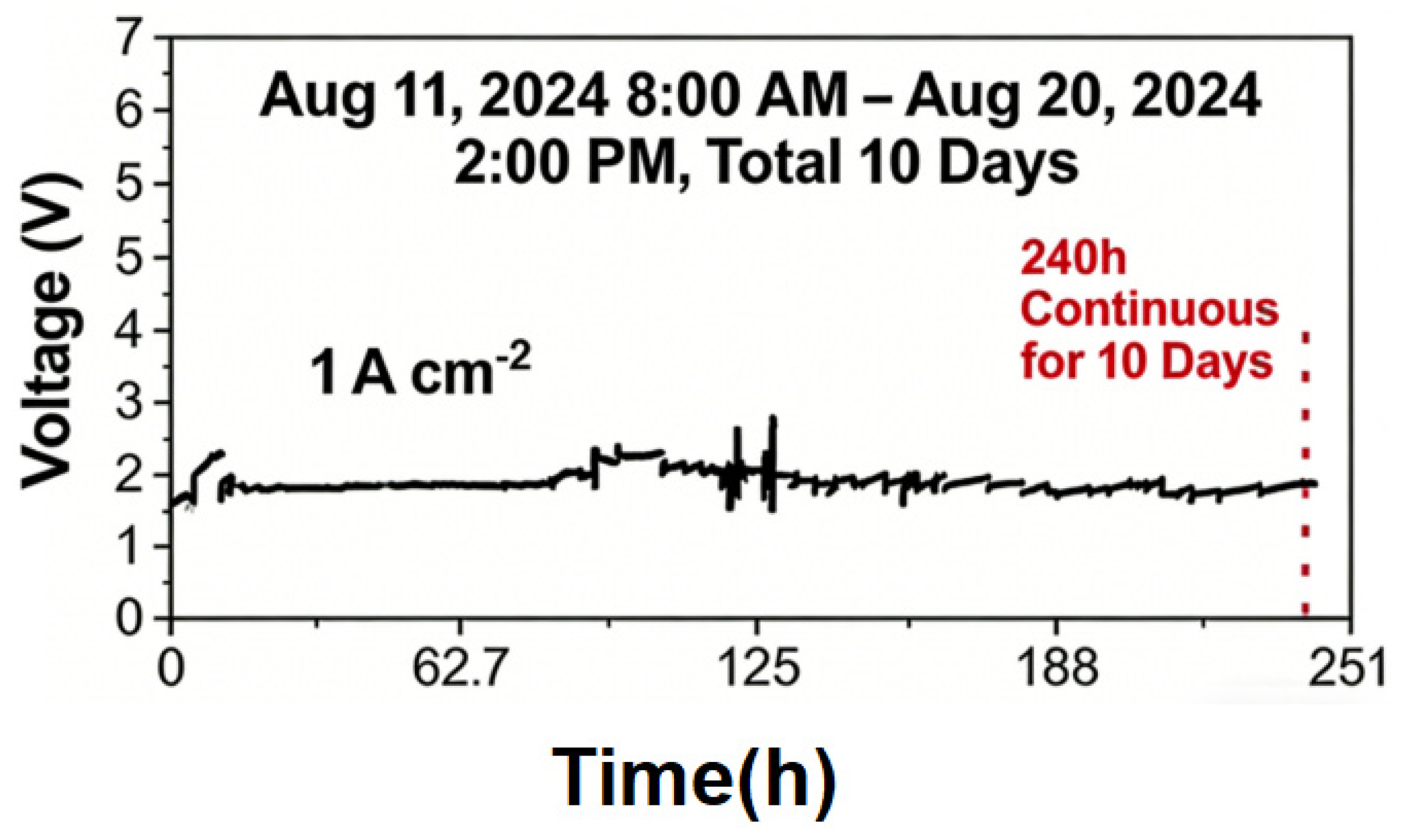

- (3)

- To address corrosion in flow channels and diaphragm perforation in the electrolyzer, optimization of the feed process and adoption of 2205 duplex stainless steel as the cell material enabled stable continuous operation for 245 h without corrosion while maintaining hydrogen purity at 96.66% ± 0.5%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, Y.; Liang, Z.F.; Wang, S. Reasonable utilization rate of renewable energy considering operational environmental cost. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 45, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chang, J.L.; Ju, P. Current status and development trend of oilfield wastewater treatment technology. Chem. Enterp. Manag. 2021, 27, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.J. Enhanced Treatment of Polymer-Flooding Wastewater by Electrocoagulation and Its Mechanism. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China, 2018. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=e_WjztTC4N1z6raVsDxrKufOEhUx52W3EFNEQA_DVLiux7hIxq2rwtBaa7UQeVpWsQqJ1pEgnmtxCouYpDHpcoPNb-kzucgBhlO-PfaGrrEIHESijrK8htq_wiV35sisS_OE9qLMB9DINROEJHHnD2fyOKgPs57pXaBSwLhDzgJat9a6gV2fr0jkoaDOYUKr&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Chen, Y.M. Study on Oil Removal Mechanism and Device Performance Optimization of Electrocoagulation for Treating Polymer-Containing Produced Water. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Experimental Study on Oil Removal Mechanism and Enhanced Oil Removal Performance of Produced Water by Electrocoagulation. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.F.; Zhang, S.H.; He, Y.; Wang, Z.H. Research status and application prospect of PEM water electrolysis for hydrogen production. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2022, 43, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. Preparation of Transition Metal Phosphides/Nanocarbon Composites and Study of Their Electrocatalytic Performance. Master’s Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2019. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=NitQnVYDOcq3xOmd4fFvOrhHPXRUIziqEyOEJs-BNzGTBNVHmN3jZf4Y0eSyoRvxTcXvN7ACr3oimEMFWqDgHEFcDFPPHj-AXjIGokeQ5izEZchxhl3h1DI3is1NeUmtSOdPfz12eFp0yMGHpBwe5AEgFGpByM9CJYTwMN96O1AbMgPaduVsTiU6HMb5SgjX&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Tabish, A.N.; Fan, L.; Farhat, I.; Irshad, M.; Abbas, S.Z. Computational fluid dynamics modeling of anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells using triple-phase boundary-based kinetics. J. Power Sources 2021, 513, 230564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, C.; Yin, L.X.; Kang, B.; Xu, J.J.; Chen, H.Y. Transient Plasmonic Imaging of Ion Migration on Single Nanoparticles and Insight for Double Layer Dynamics. Angew. Chem. 2022, 61, e202117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Wu, X.; Fan, L.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Xie, Z. Effect of Different Draw Solutions on Concentration Polarization in a Forward Osmosis Process: Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Validation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, E.D.; Li, G.F.; Zhang, J.L.; Ke, C.C. Effect of different parameters of titanium felt-based porous transport layer on polarization performance of PEMWE. Chin. J. Power Sources 2024, 48, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Fu, X.; Deng, Z.; Kim, J.S.; Li, X. A CFD model for analyzing multiphysics coupling and efficiency optimization in a PEMEC. J. Power Sources 2025, 62, 235678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Study on the Production of Ammonium Persulfate by Ion Exchange Membrane Electrolysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Lu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Deng, J. Experimental study on bubble drag reduction by the turbulence suppression in bubble flow. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 272, 113804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, S.; Dong, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y. Engineering the Coordination Sphere of Isolated Active Sites to Explore the Intrinsic Activity in Single-Atom Catalysts. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoche, L.K.; Landgren, J.; Leddy, J. (Invited) Fick’s II Law and Deploying Spatially Varying Diffusion Coefficients on Electrodes. Meet. Abstr. 2017, MA2017-02, 2032. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=NitQnVYDOcp4gat0u1eEfbl73ZUsNDW2cWMK7rNkJrL6ysQS8fj13CXd6cVIgIFTxe1hL5fpOIh1mgvlXcEV7Bx1DwsVgEbPj8uwHpI4Oz-NZWJ8Ngqz4c91zgfPDp1yXwGSngTiL2A2QPUMvkzF-gFcYRszzN8V08fOFGv3KcfVEvnCxkmjTU8pL8IZLGTA&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 30 December 2025). [CrossRef]

| Analytical Indicators | Method of Determination | Principal Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Turbidity | Spectrophotometry | WZS-186 Digital Turbidity Meter/ShangHai/China |

| Suspended solids content | Photometric method | HM-SS Suspended Solids Detector/ShanDong/China |

| Oil content | Spectrophotometry | A360 Ultraviolet–Visible Spectrophotometer/ShangHai/China |

| Hydrogen purity | External standard method for thermal conductivity detector | NK-200A Hydrogen Analyzer/ShanXi/China |

| Testing Metrics | Water Sample 1 | Water Sample 2 | Water Sample 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil content (mg/L) | 115.1 | 113.2 | 115.1 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 350.2 | 351.2 | 350.8 |

| Suspended solids (mg/L) | 1800.5 | 1815.3 | 1785.1 |

| Chloride content (mg/L) | 6948.1 | 6949.6 | 6943.4 |

| pH | 7.6 | 7.5 | 7.3 |

| Hardness index | 17 | 16 | 18 |

| Test Parameters | Water Quality Prior to Treatment | Treated Water Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Oil content (mg/L) | 115.1 | 23.1 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 350.2 | 46.2 |

| Suspended solids (mg/L) | 1800.5 | 85.3 |

| Chloride ion content (mg/L) | 6948.1 | 5232.8 |

| pH | 7.6 | 7.2 |

| Hardness index | 17 | 16 |

| Variables | Optimal Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|

| Electrolyte pH | 6 M KOH |

| Current intensity | 1 A cm−2 |

| Flow rate | 0.8 L min−1 |

| Temperature | 85 °C |

| Processing Time (min) | Effectiveness of Oily Wastewater Treatment | Hydrogen Production Efficiency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil Content (mg/L) | Turbidity (NTU) | Suspended Solids Content (mg/L) | Hydrogen Purity (%) | Voltage of 6M KOH, 21 (0.8 L/min) Cell Voltage (V) at 1 A cm−2 Current Density | |

| 0 | 112.86 | 260 | 1639.05 | - | 2.231 |

| 20 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 40 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 60 | 7.6263 | 36.2 | 65.041 | 88.13 | 2.279 |

| 80 | 6.0828 | 12.9 | 13.16 | 96.69 | 1.856 |

| 100 | 6.5721 | 15.3 | 14.136 | 95.19 | 1.889 |

| 120 | 6.1245 | 15.2 | 17.190 | 96.12 | 1.876 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, P.; Zha, G.; Zhang, C.; Han, W.; Wang, F.; Dong, B.; Jiang, W. Integrated Electrochemical–Electrolytic Conversion of Oilfield-Produced Water into Hydrogen. Processes 2026, 14, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010173

Fan P, Zha G, Zhang C, Han W, Wang F, Dong B, Jiang W. Integrated Electrochemical–Electrolytic Conversion of Oilfield-Produced Water into Hydrogen. Processes. 2026; 14(1):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010173

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Pengjun, Guangping Zha, Chao Zhang, Weikang Han, Fuli Wang, Bin Dong, and Wenming Jiang. 2026. "Integrated Electrochemical–Electrolytic Conversion of Oilfield-Produced Water into Hydrogen" Processes 14, no. 1: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010173

APA StyleFan, P., Zha, G., Zhang, C., Han, W., Wang, F., Dong, B., & Jiang, W. (2026). Integrated Electrochemical–Electrolytic Conversion of Oilfield-Produced Water into Hydrogen. Processes, 14(1), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010173