A Mechanical Error Correction Algorithm for Laser Human Body Scanning System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Based on an analysis of error sources of the entire system, this paper clarified that mechanical error of the system was unavoidable and directly affected the measurement accuracy of the system.

- (2)

- To obtain theoretical data of several selected standard test points, and to conduct a quantitative analysis of mechanical error by comparing the theoretical data with actual data, this paper developed a simulation calculation system in accordance with the working principle and mathematical model of the scanner.

- (3)

- To reduce mechanical error, a mechanical error correction model and an interpolation compensation method for the system were established.

- (4)

- A mechanical error correction experiment using a standard cylinder was designed. The results of the correction experiment were analyzed. The experimental result verified the correctness and effectiveness of the mechanical error correction model and an interpolation compensation method of the system.

- (5)

- To further verify the accuracy and reliability of the measurement result when the system used human bodies as measured objects, a comparative experiment was designed. The results of the comparative experiment demonstrated that the absolute error of the system for 3D measurement of a large-sized human body is less than 2 mm, and the relative error is less than 1%, which can meet the needs of fields such as clothing design and production.

2. Related Work

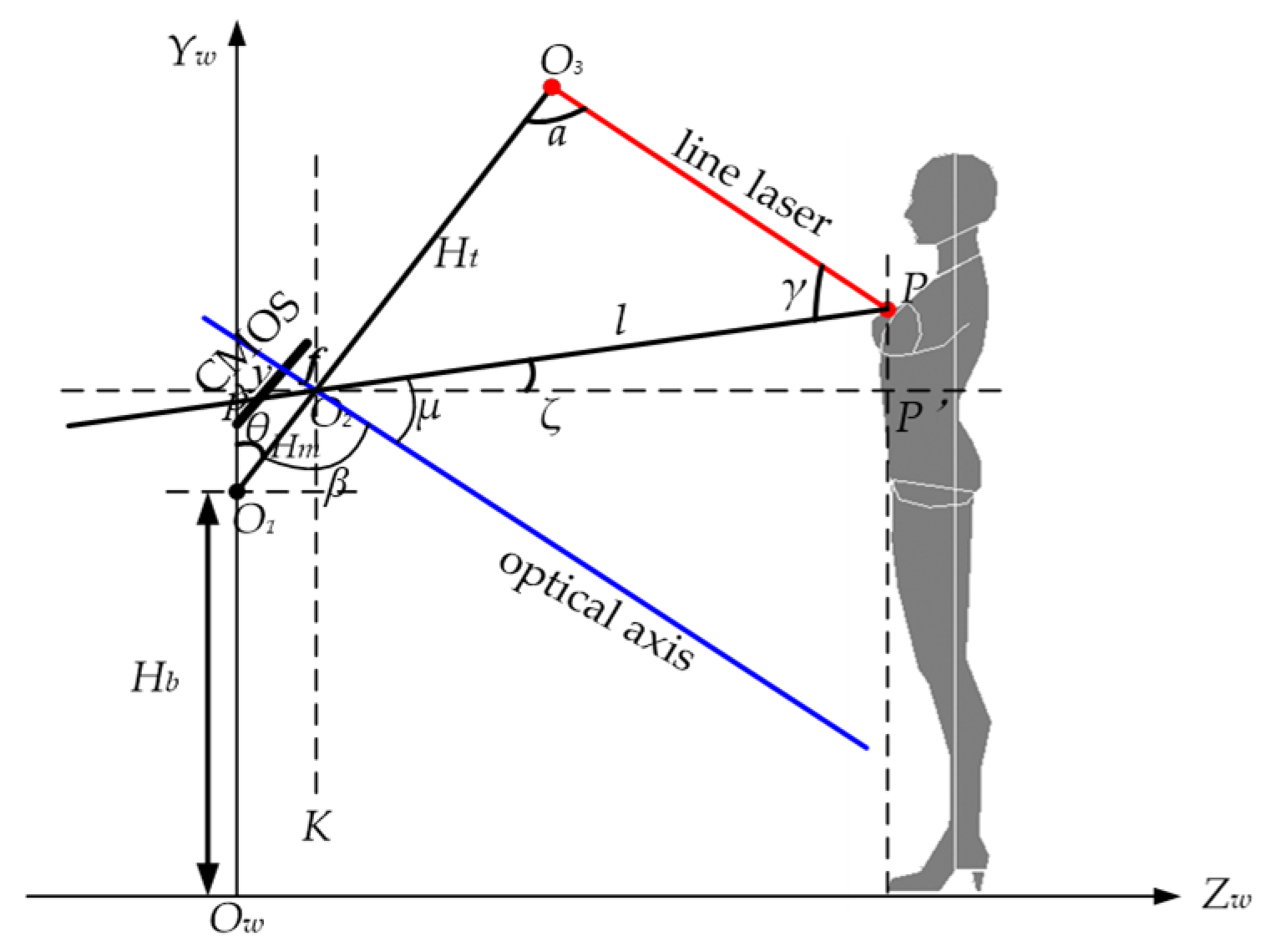

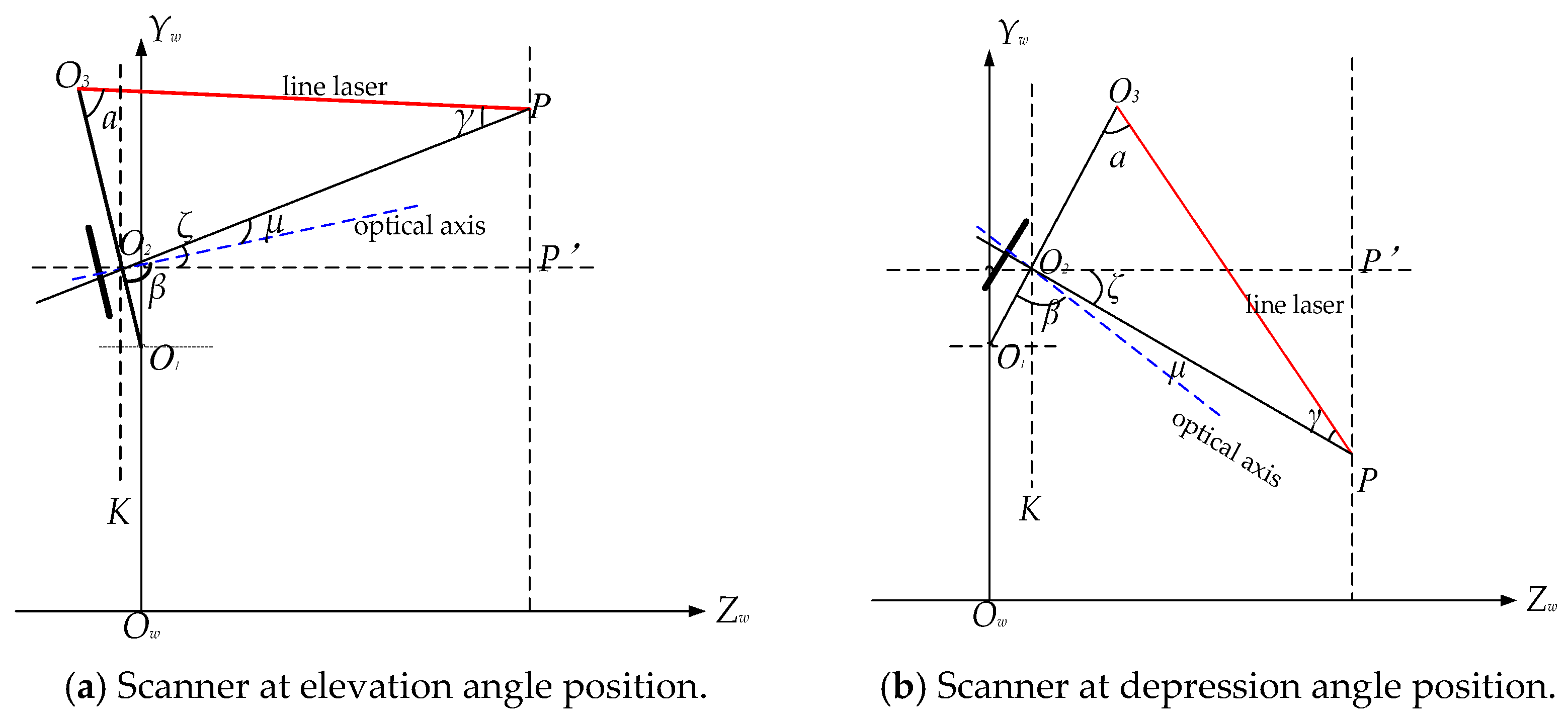

2.1. Establishment of the System Model

- (1)

- Hb: The vertical distance from the pan-tilt to the ground;

- (2)

- Hm: The distance from pan-tilt to the optical center of the industrial camera;

- (3)

- Ht: The distance from the optical center to the line laser;

- (4)

- θ: The rotation angle of the pan-tilt, which represented the angle between the rotating arm (O1O3) and the positive direction of the YW axis in the world coordinate system;

- (5)

- f: The effective focal length of the camera optical lens;

- (6)

- a: The angle between the light plane and the rotating arm;

- (7)

- β: The angle between the camera optical axis and the rotating arm.

- (1)

- Human body remains in a fixed position.

- (2)

- The industrial camera and the laser are made to work in linkage with each other via a numerical control pan-tilt head, and perform a pitching motion around the pan-tilt head.

- (3)

- During the motion processes, the projection position of the line laser and the field of view of the camera are changed to form a dynamic light strip. And it is ensured that the light strip is always within the camera’s field of view.

- (4)

- The human body is a dynamic object. Movements such as breathing or slight involuntary body sway can introduce measurement error. The longer the scanning time, the more pronounced such error caused by spontaneous body movements becomes. Therefore, rapidity is a key requirement for human body measurement.

- (5)

- The scanning time refers to the duration required to complete a single scan, and its length is determined by the height of the scanned object. For human body measurement, the rotation angle of pan-tilt required to complete a single human body scan varies depending on the subject’s height. For example, when scanning a human body with a height of 175 cm, the pan-tilt generally needs to rotate 235 steps (a step angle is 0.225°) to fully scan the measured subject. Given that the time required for the pan-tilt to rotate one step is 67 ms, the scanning time is approximately 15.74 s.

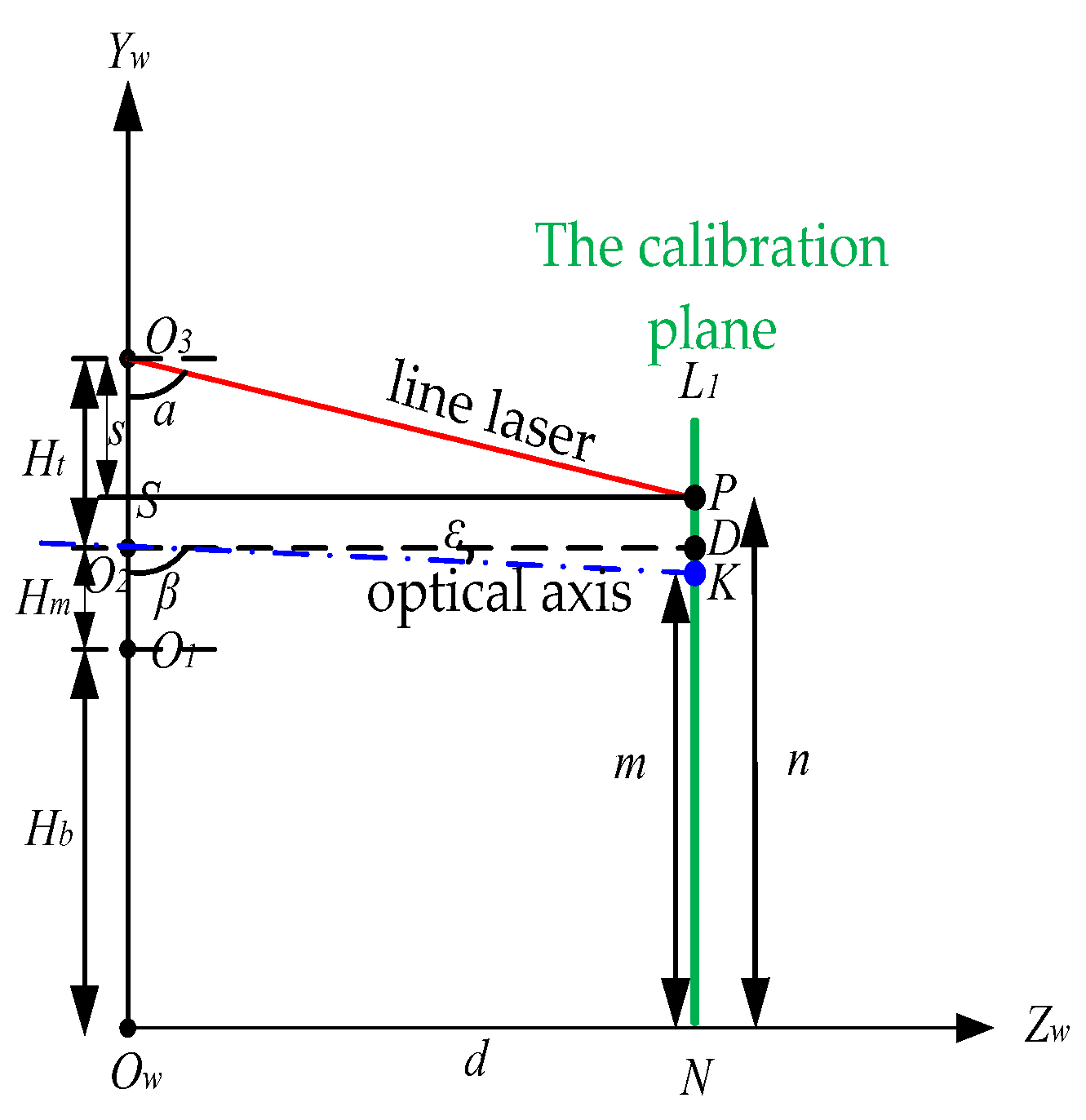

2.2. Calibration Method for Parameters (Angle a and Angle β)

2.3. Analysis of Error Sources

- (1)

- The ranging errors come from direct measurements of Hb, Hm, and Ht. These errors could be mitigated by averaging multiple measurements.

- (2)

- The calibration errors of parameters (angles a and β). Angle a and angle β were determined by using the calibration method established in Section 2.2. The error reduction was achieved by averaging the result from multiple calibrations.

- (3)

- The imaging error in the optical module. Due to manufacturing and assembly tolerances inherent in the CMOS industrial camera and the optical lens used in the scanner, deviations inevitably occurred in the effective focal lengths (fx and fy) of the lens, as well as the image coordinates (u0,v0) of the camera’s optical axis center point. The magnitude of these deviations was determined by the calibration accuracy of the industrial camera. This paper adopted Zhang Zhengyou’s planar template calibration method. To mitigate the error and to ensure calibration accuracy, this paper employed an averaging approach to calibrations and conducted error analysis of the calibration results.

- (4)

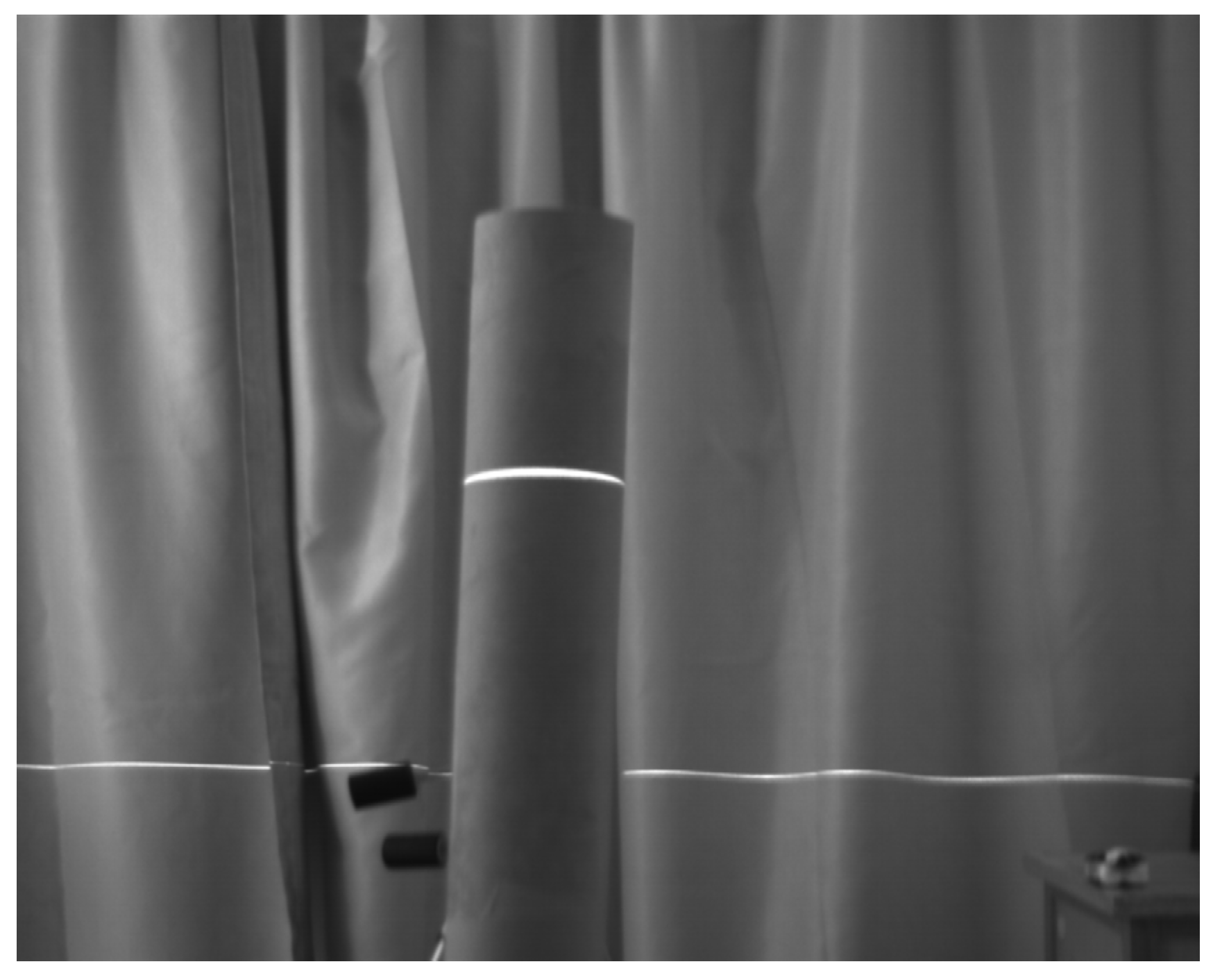

- The extraction error of the pixel coordinates at the optical band center position. The projection point’s image coordinates (xi,yi) were calculated from the pixel coordinates (ui,vi) at the optical band center position. For this type of extraction error, by establishing a target region optimization and recognition algorithm in the image processing, such error could effectively be reduced. This paper adopted the monochrome CMOS camera with a signal-to-noise ratio of 46 dB. The camera can not only capture images with sufficient resolution, but also features high sensitivity in low-light environments and stable performance. After performing cubic Bezier spline interpolation fitting on the pixel coordinate points of each group of pixel columns in the image, the maximum points of each fitted cubic Bezier spline curve are the center position points of human body laser stripes in each corresponding column.

- (5)

- The mechanical motion error. During actual scanning measurements, the scanner’s one-dimensional numerical control pan-tilt inevitably introduced rotational angle deviation. Additionally, the assembly error of the mechanical arm occurred during each installation and operation process, affecting the situation of the optical plane. Mechanical errors like pan-tilt rotation angle deviation critically affected the spatial accuracy of the optical plane during scanning. The mechanical error caused a discrepancy between the theoretical and actual positions where the optical plane intersected the human body. The spatial deviation of the optical plane was transferred to target pixels, which led to extraction errors in the target pixel coordinates (ui,vi) during image processing. Consequently, it introduced amplified error in the spatial position reconstruction of the human body. Even the slightest rotational deviation in mechanical motion significantly impacted the extracted target pixel coordinates, thereby affecting the overall measurement accuracy of the system. Next, this paper focused on investigating the characteristics, causes, and correction algorithms for the error.

3. Methods

4. Experimental Results and Analyses

4.1. Experiment on Standard Cylinder Scanning

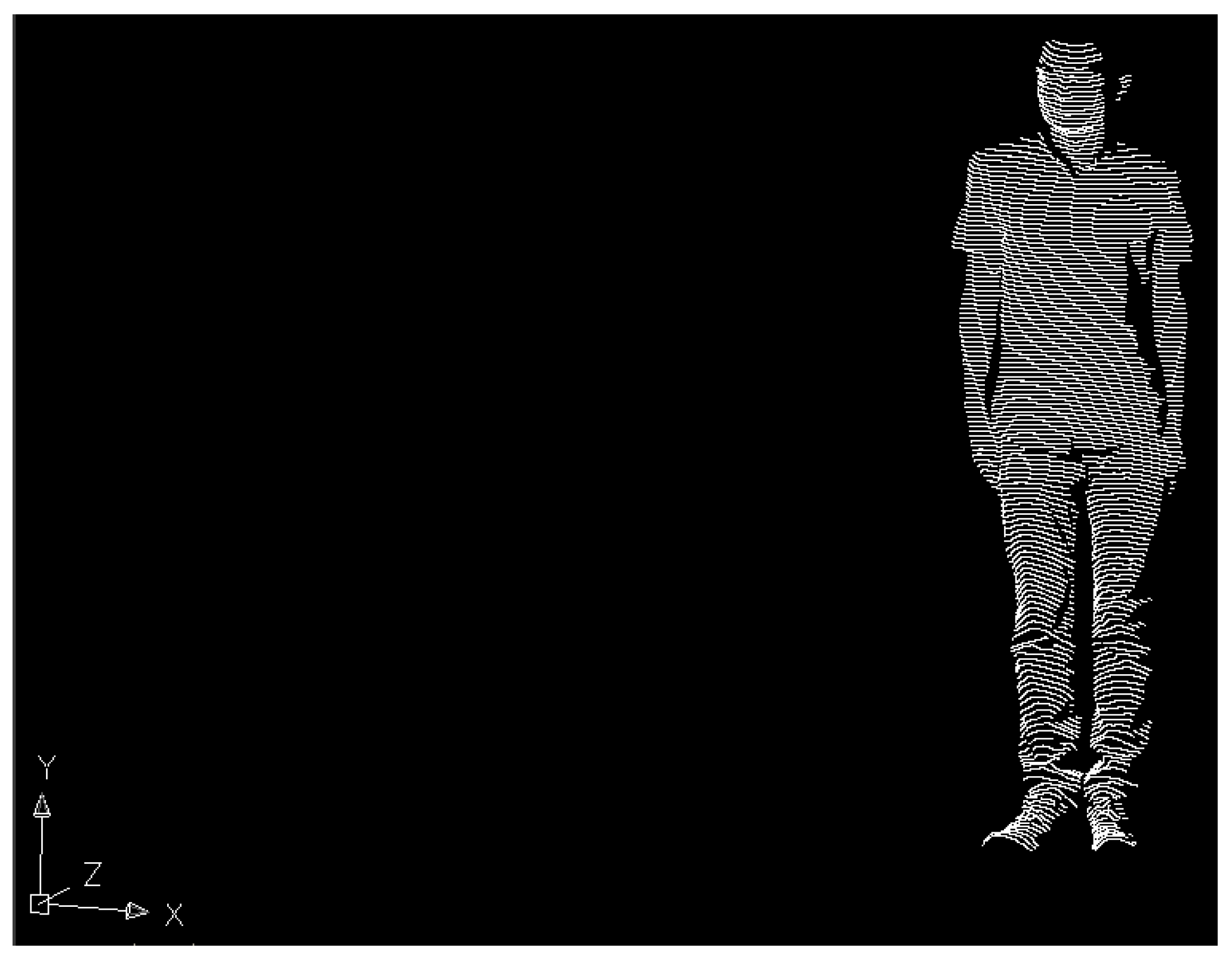

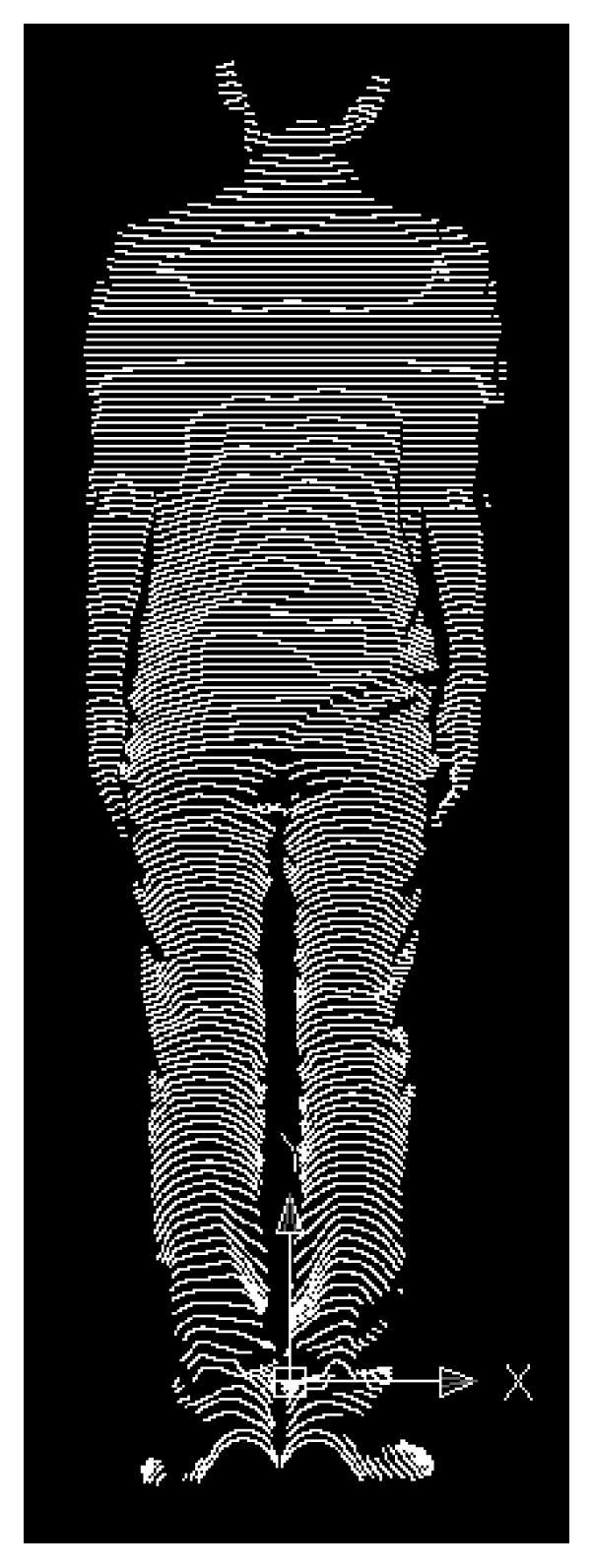

4.2. Comparative Experiment

4.3. Experiment on Fan Blade Measurement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doule, O.; Kobrick, R.L.; Crisman, K.; Skuhersky, M.; Lopac, N.; Fornito, M.J.; Covello, C.; Banner, B.C. IVA spacesuit for commercial spaceflight-upper body motion envelope analysis. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 186, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Li, Y.Z.; Yuan, M. Joint modeling and dynamic analysis of the micro-environment and life support performance of extravehicular spacesuits. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2024, 16, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.Q.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Peng, T.; Zhang, X.Y.; Cai, Y.C.; Zhang, X.J.; Tang, R.Z. From digital human modeling to human digital twin: Framework and perspectives in human factors. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jia, H.K.; Lu, Y.; Wu, A.A.; Zhang, X.D.; Lin, B.; Jiyan, Z.; Wang, X.Y.; Yu, L.D. Research on the application of a dynamic programming method based on geodesic distance for path planning in robot-assisted laser scanning measurement of free-form surfaces. Measurement 2024, 238, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenpong, P.; Kongtanee, K.; Chaiprasittigul, P.; Sathapornprasath, K.; Charoenpong, T. Automatic body measurement for straight-tube mountain bike size selection using closest size classification. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 100831–100849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, L.; Eder, M.; Hollweck, R.; Zimmermann, A.; Settles, M.; Schneider, A.; Endlich, M.; Mueller, A.; Schwenzer-Zimmerer, K.; Papadopulos, N.A.; et al. Comparison between breast volume measurement using 3D surface imaging and classical techniques. Breast 2007, 16, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.F.; He, Z.L.; Liu, C.; Liu, T.R.; Lin, Y.C.; Zhang, P.S.; Ming, W.K. Preferences for the ocular region aesthetics and elective double eyelid surgery in Chinese: A nationwide discrete choice experiment. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2024, 102, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Sun, G.F.; Hua, S.C.; Yu, W.; Meng, C.Z.; Han, Q.; Kim, J.; Guo, S.J.; Shen, G.Z.; Li, Y. Multifunctional all-nanofiber cloth integrating personal health monitoring and thermal regulation capabilities. InfoMat 2025, 7, e12629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kwon, K.; Kim, C.; Youm, S. Development of a non-contact sensor system for converting 2D images into 3D body data: A deep learning approach to monitor obesity and body shape in individuals in their 20s and 30s. Sensors 2024, 24, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.M.; Huang, X.P.; Xia, G.F.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.J. A high-precision automatic extraction method for shedding diseases of painted cultural relics based on three-dimensional fine color model. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhou, K. Key technologies for the digitization of cultural relics and their application in digital museums. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2025, 7, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Li, G.Q.; Li, T.C.; Lv, J.P.; Mitrouchev, P. Design of a multi-sensor information acquisition system for mannequin reconstruction and human body size measurement under clothes. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 3750–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.W.; Huang, R.; Wang, Z.H.; Lyu, Y.R.; Liu, H.H.; Sun, Y.X. Measurements-to-body: 3D human body reshaping based on anthropocentric measurements. J. Text. Inst. 2024, 16, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Li, G.Q.; Li, M.; Cheng, X.G.; Chen, F. Design of underclothing 3D human body measurement and reconstruction system for clothed individuals. Text. Res. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.J. 3D garment human body feature point recognition and size measurement based on SURF algorithm. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2025, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzeszowski, T.; Dziadek, B.; França, C.; Przednowek, K.; Gouveia, E.R.; Przednowek, K. System for estimation of human anthropocentric parameters based on data from Kinect v2 depth camera. Sensors 2023, 23, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.H.; Ahmad, H.; Yang, S.Y.; Michael, B.H.; David, P. Non-contact human body voltage measurement using Microsoft Kinect and field mill for ESD applications. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2019, 61, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C. Non-contact human body dimension estimation methods based on deep learning: A critical analysis. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2024, 52, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, W.Q.; Chen, G.D.; Xie, Z.X.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhang, C.T. Measurement of human body parameters for human postural assessment via single camera. J. Biophotonics 2023, 16, e202300041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, L.; Peng, X.Y.; Tian, X.H. Method of automatic measurement of human size based on depth camera. J. Chin. Comput. Syst. 2019, 4, 2202–2208. Available online: http://xwxt.sict.ac.cn/EN/abstract/abstract5150.shtml (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Wu, R.; Ma, L.; Chen, Z.; Shi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Patil, A.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Stretchable spring-sheathed yarn sensor for 3D dynamic body reconstruction assisted by transfer learning. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasinetti, S.; Nuzzi, C.; Luchetti, A.; Zanetti, M.; Lancini, M.; Cecco, D.M. Experimental procedure for the metrological characterization of time-of-flight cameras for human body 3D measurements. Sensors 2023, 23, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherdchusakulchai, R.; Thoumrungroje, S.; Tungpanjasil, T.; Pimpin, A.; Srituravanich, W.; Damrongplasit, N. Contact less body measurement system using single fixed-point RGBD camera based on pose graph reconstruction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 84363–84373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, R.; Akram, S.; Naderi, H.; Hashenmi-Nejad, N.; Choobineh, A.; Baneshi, M.R.; Feyzi, V. Technical report on the modification of 3-dimensional non-contact human body laser scanner for the measurement of anthropometric dimensions: Verification of its accuracy and precision. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 8, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lin, S.; Wang, Z. Cluster size intelligence prediction system for young women’s clothing using 3D body scan data. Mathematics 2024, 12, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhofer, K.; Knopfli, C.; Achermann, B.; Lorenzetti, S.R. Feasibility of using laser imaging detection and ranging technology for contactless 3D body scanning and anthropometric assessment of athletes. Sports 2024, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, X.B.; Zhao, G.K.; Xi, J.T. Laser speckle projection based handheld anthropometric measurement system with synchronous redundancy reduction. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Xi, J.T.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, X.B. Infrared laser speckle projection based multi sensor collaborative human body automatic scanning system. Machine 2021, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutti, A.G.; Santi, M.G.; Hansen, A.H.; Fatone, S. Accuracy, repeatability, and reproducibility of a hand-held structured-light 3D scanner across multi-site settings in lower limb prosthetics. Sensors 2024, 24, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, D.H.; Guan, J.H.; Li, X.F. A 3D scanner of the whole body based on structured light. J. Hua Zhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2004, 10, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Nam, Y.; Cho, D.; Kang, T. Development of Three-dimensional Body Scan Method in Measuring Body Surface. Text. Res. J. 2006, 76, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.H.; Peng, X.Y.; Liu, L.W.; Xia, Q. Automatic human body feature extraction and personal size measurement. J. Vis. Lang. Comput. 2018, 47, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, W.; Sons, L. An innovative method for human height estimation combining video images and 3D laser scanning. J. Forensic Sci. 2024, 69, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petra, U.; Petr, H.B.; Mikoláš, J.A. Testing photogrammetry-based techniques for three-dimensional surface documentation in forensic pathology. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 250, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.T.; Kyung, C.J.; Seung, T.K.; Jongseok, K.; Seung, B.C. 3D body scanning measurement system associated with RF imaging, Zero-padding and Parallel Processing. Meas. Sci. Rev. 2016, 16, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Cai, N. A high-precision multi-beam optical measurement method for cylindrical surface profile. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| YW Actual Measured Value (cm) | YW’ Theoretical Calculated Value (cm) | Spatial Position Error ΔYW (mm) | Target Pixel Deviation Δv (Pixel) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −7.875 | 135.1132 | 135.2676 | −1.544 |

| 0 | 104.6401 | 104.6450 | −0.049 |

| 19.125 | 80.7761 | 80.8743 | −0.982 |

| Rotation Angle (Degrees) | Measured Value Before Calibration YW (cm) | Error Value (mm) | Measured Value After Calibration YW″ (cm) | Error Value (mm) | Error Reduction (mm) | Error Reduction Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −7.875 | 135.1132 | −1.544 | 135.1916 | −0.648 | 0.896 | 58.03% |

| 0 | 104.6401 | −0.049 | 104.6419 | −0.031 | 0.018 | 36.73% |

| 19.125 | 80.7761 | −0.982 | 80.8342 | −0.401 | 0.581 | 59.16% |

| Rotation Angle (Degrees) | Measured Value Before Calibration ZW (cm) | Error Value (mm) | Measured Value After Calibration ZW″ (cm) | Error Value (mm) | Error Reduction (mm) | Error Reduction Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −7.875 | 150.2547 | 2.547 | 150.1047 | 1.047 | 1.500 | 58.89% |

| 0 | 150.0048 | 0.048 | 150.0031 | 0.031 | 0.017 | 35.41% |

| 19.125 | 150.1678 | 1.678 | 150.0990 | 0.990 | 0.688 | 41.00% |

| Rotation Angle (Degrees) | Measured Value Before Calibration XW (cm) | Error Value (mm) | Measured Value After Calibration XW″ (cm) | Error Value (mm) | Error Reduction (mm) | Error Reduction Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −7.875 | 8.2617 | 2.617 | 8.1090 | 1.090 | 1.527 | 58.34% |

| 0 | 8.0019 | 0.019 | 8.0013 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 31.57% |

| 19.125 | 8.1473 | 1.473 | 8.0947 | 0.947 | 0.526 | 35.70% |

| Rotation Angle (Degrees) | Measured Value After Calibration XW″ (cm) | Theoretical Value XW′ (cm) | Spatial Position Error ΔX (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1.0106 | 8.0124 | 8.0000 | 0.124 |

| −0.7042 | 8.0093 | 8.0000 | 0.093 |

| −0.3978 | 8.0061 | 8.0000 | 0.061 |

| 0 | 8.0019 | 8.0000 | 0.019 |

| 0.3978 | 8.0042 | 8.0000 | 0.042 |

| 0.7042 | 8.0055 | 8.0000 | 0.055 |

| NO. | Marker Points | Laser Human Body Scanning System (cm) | Lectra Human Body Measurement System (cm) | Comparison Error (cm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Y1 | Z1 | X2 | Y2 | Z2 | ΔX | ΔY | ΔZ | ||

| 1 | Cervical vertebra point | 1.25 | 148.88 | 102.64 | 1.30 | 148.73 | 102.51 | −0.05 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| 2 | Lateral cervical point (left) | 7.11 | 147.57 | 104.22 | 7.34 | 147.41 | 104.19 | −0.23 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| 3 | Lateral cervical point (right) | −8.63 | 146.01 | 104.15 | −8.80 | 145.88 | 104.11 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| 4 | Acromial point (left) | 18.84 | 142.02 | 106.78 | 19.01 | 142.21 | 106.60 | −0.17 | −0.19 | 0.18 |

| 5 | Acromial point (right) | −19.84 | 142.05 | 106.52 | −20.07 | 142.16 | 106.45 | 0.23 | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| 6 | Lumbar point (left) | 15.29 | 110.10 | 93.44 | 15.14 | 110.27 | 93.32 | 0.15 | −0.17 | 0.12 |

| 7 | Lumbar point (right) | −14.95 | 110.58 | 93.21 | −14.90 | 110.76 | 93.29 | −0.05 | −0.18 | −0.08 |

| 8 | Posterior protrusion point of the hip (left) | 10.75 | 90.80 | 132.34 | 10.96 | 90.67 | 132.23 | −0.21 | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| 9 | Posterior protrusion point of the hip (right) | −11.08 | 90.44 | 133.17 | −11.18 | 90.58 | 133.20 | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.03 |

| 10 | Mid-knee point (left) | 12.30 | 40.95 | 105.15 | 12.43 | 40.92 | 105.20 | −0.13 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| 11 | Mid-knee point (right) | −10.91 | 40.61 | 105.37 | −11.17 | 40.45 | 105.22 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| The Measured Dimension | True Value (mm) | 3D Measured Value (mm) | The Absolute Error (mm) | The Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | 98.10 | 98.97 | −0.87 | 0.71% |

| DB | 131.21 | 131.59 | −0.38 | 0.56% |

| HR | 500.85 | 500.25 | 0.60 | 0.57% |

| HL | 531.93 | 531.15 | 0.78 | 0.70% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, K.; Ma, F.; Yang, M. A Mechanical Error Correction Algorithm for Laser Human Body Scanning System. Processes 2026, 14, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010158

Wang Y, Ren J, Xue Y, Liu K, Ma F, Yang M. A Mechanical Error Correction Algorithm for Laser Human Body Scanning System. Processes. 2026; 14(1):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010158

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yue, Jun Ren, Yuan Xue, Kaixuan Liu, Fei Ma, and Maoya Yang. 2026. "A Mechanical Error Correction Algorithm for Laser Human Body Scanning System" Processes 14, no. 1: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010158

APA StyleWang, Y., Ren, J., Xue, Y., Liu, K., Ma, F., & Yang, M. (2026). A Mechanical Error Correction Algorithm for Laser Human Body Scanning System. Processes, 14(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010158