Leachate Analysis of Biodried MSW: Case Study of the CWMC Marišćina

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- To confirm the landfilling compliance of the waste to landfill in accordance with the requirements for leaching parameters prescribed in the Landfill Ordinance [7].

- (b)

- To characterize the chemical composition of the leachate in the as-it-is state, immediately after the leachate was expelled from the biodried waste sample due to a compactive effort.

- (c)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Used Technology

2.2. Waste Characterization Methodology

2.3. Leachate Preparation Methods

2.3.1. Method 1

2.3.2. Method 2

2.3.3. Method 3

2.4. Analytical Characterization Methods

3. Results

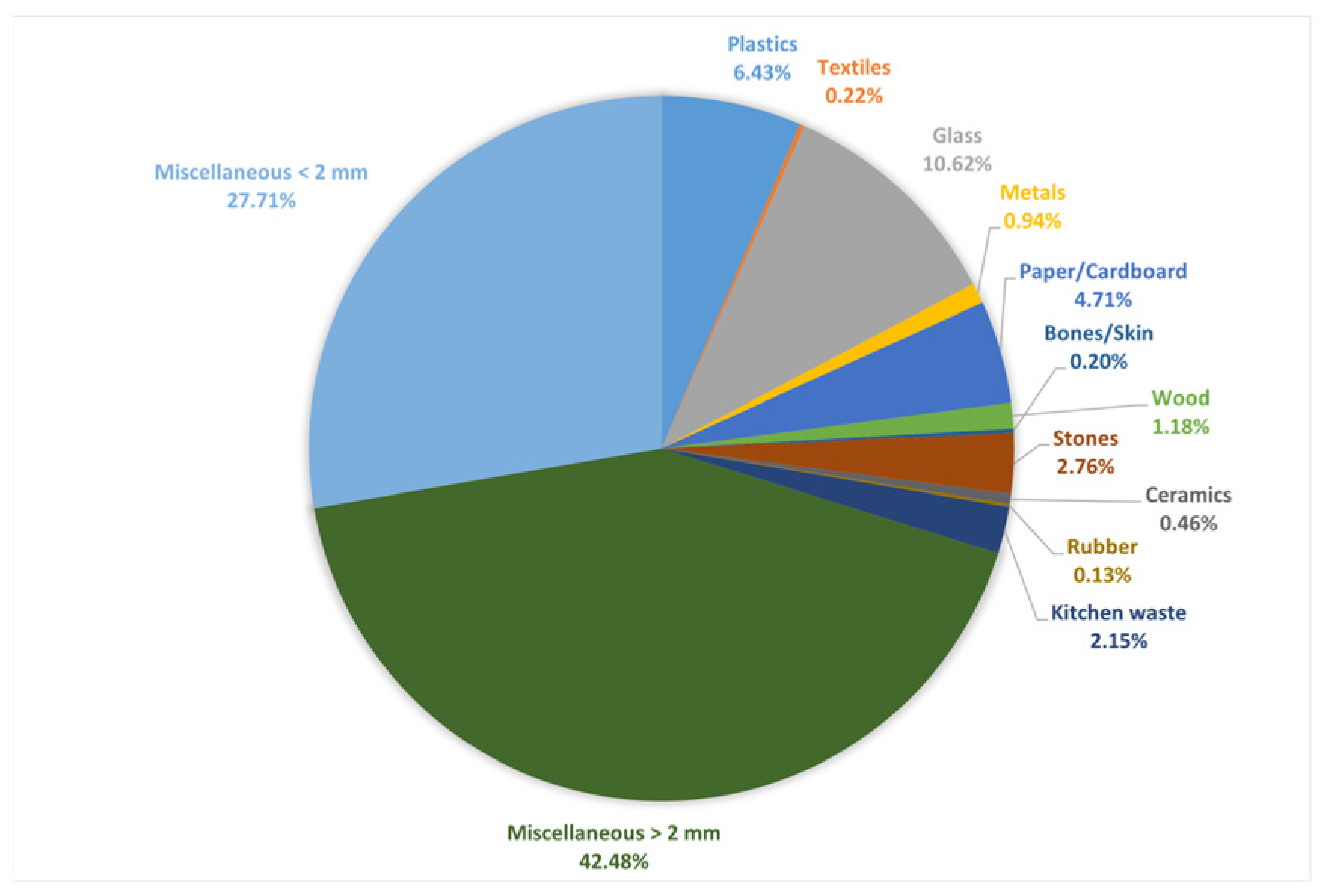

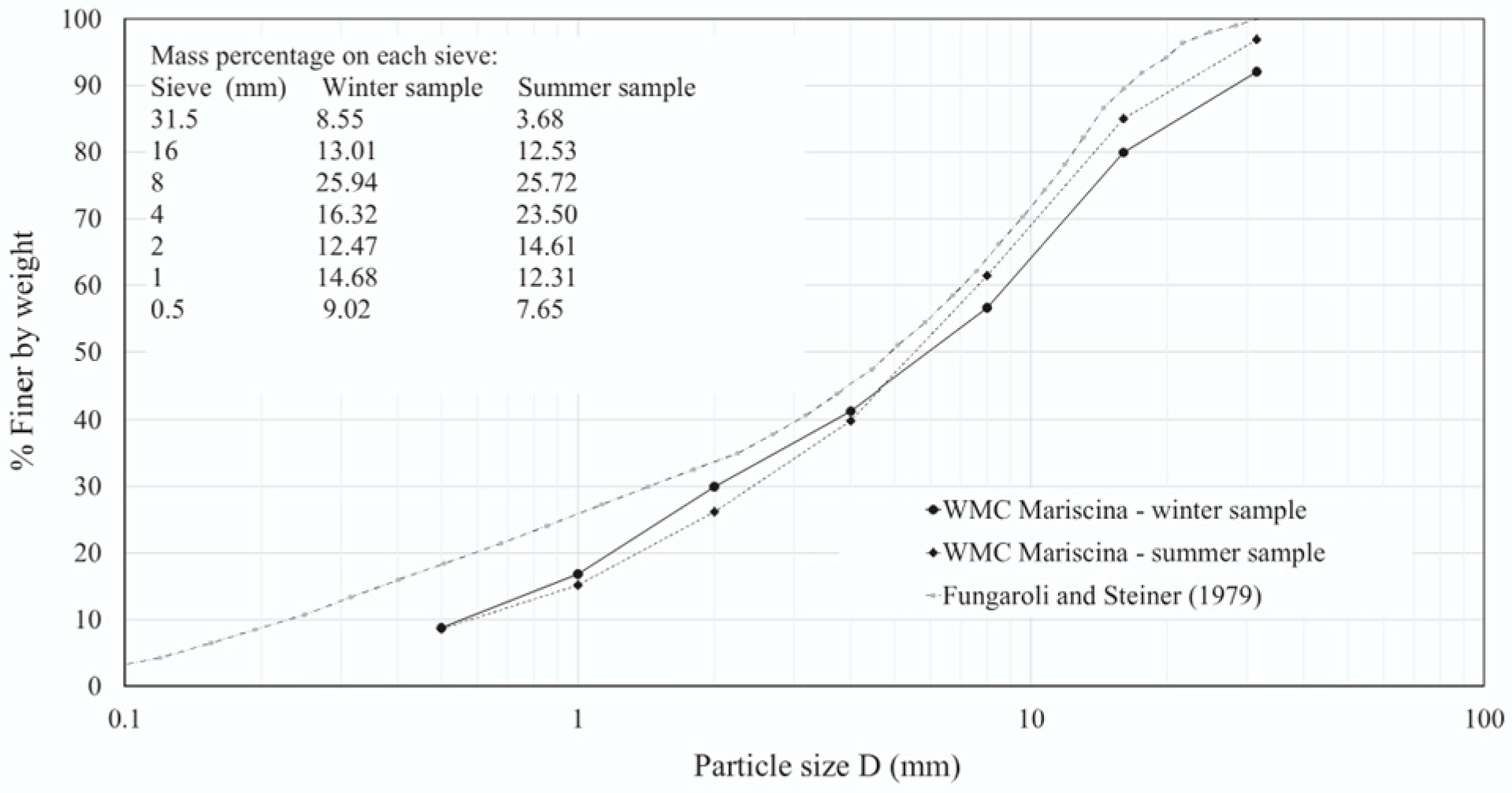

3.1. Physical Characteristics of Waste

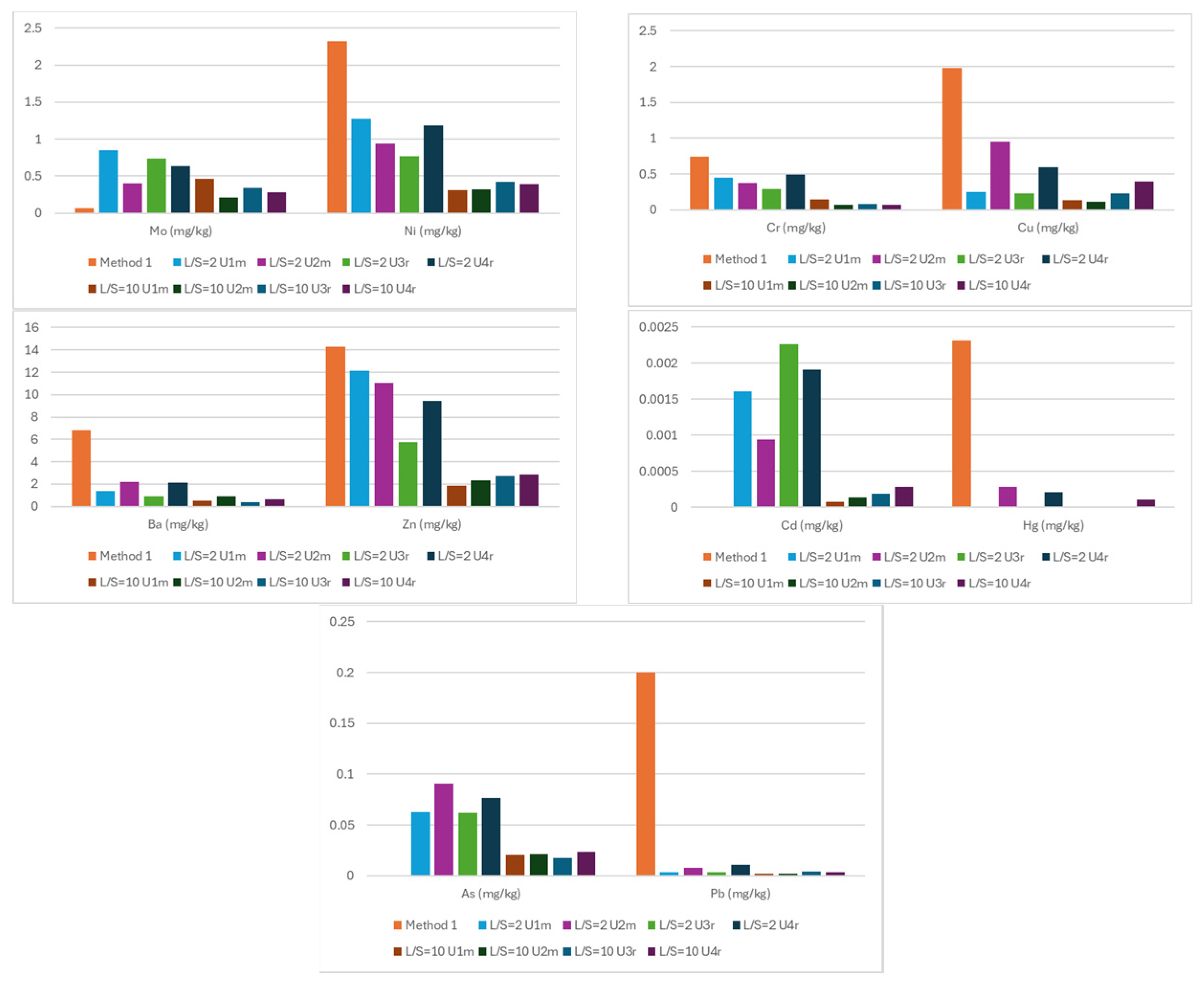

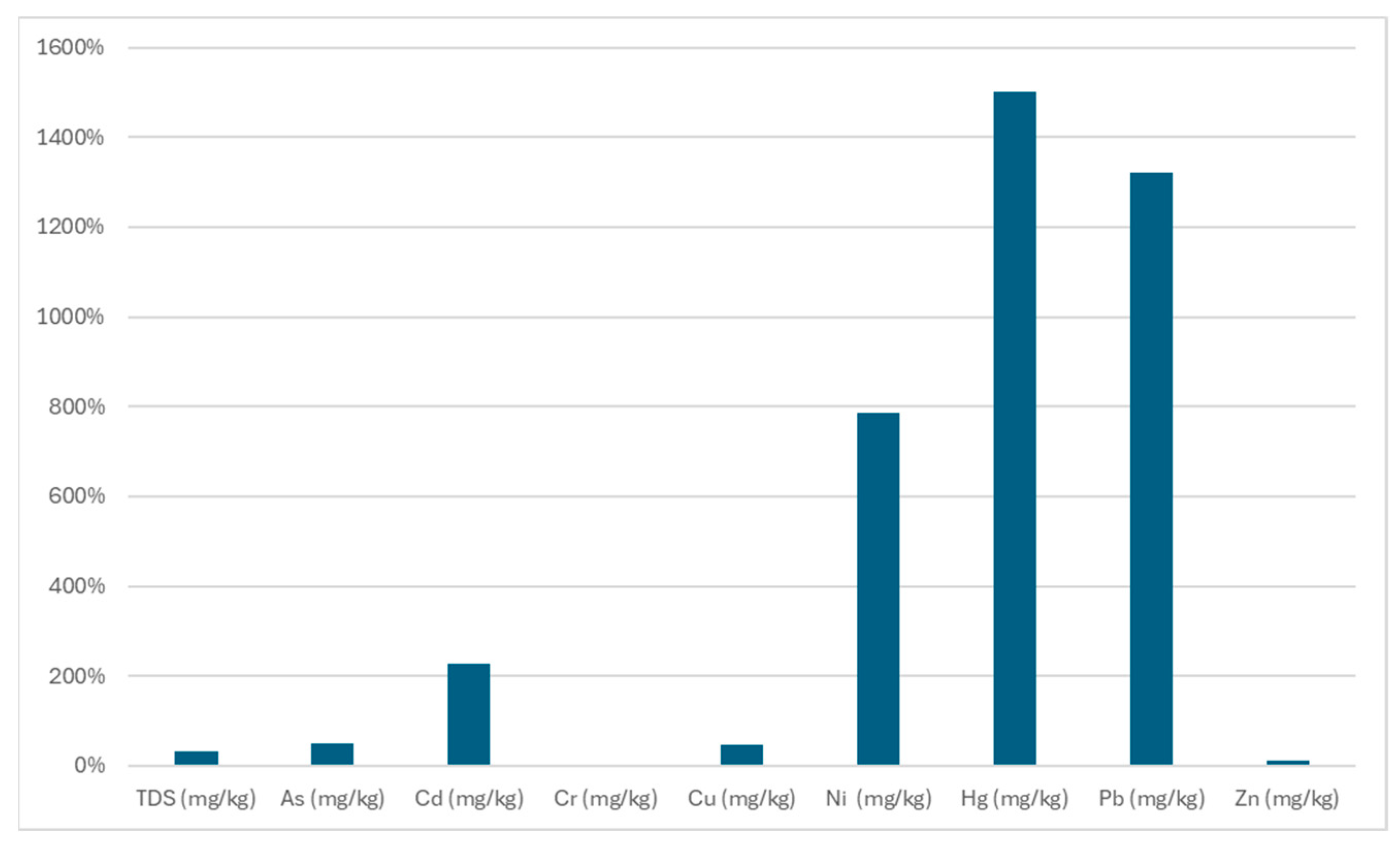

3.2. Chemical Characteristics of Waste

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baawain, M.; Al-Mamun, A.; Omidvarborna, H.; Al-Amri, W. Ultimate Composition Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste in Muscat. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, H.K.; Guvenc, S.Y.; Guvenc, L.; Demir, G. Municipal Solid Waste Characterization According to Different Income Levels: A Case Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Asam, Z.-U.-Z.; Abbas, M.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Farid, M.; Haider, M.A.; Musharavati, F.; Rehan, M.; Khan, M.I.; Naqvi, M.; et al. Evaluating Heavy Metal Contamination from Leachate Percolation for Sustainable Remediation Strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambone, F.; Scaglia, B.; Scotti, S.; Adani, F. Effects of Biodrying Process on Municipal Solid Waste Properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 7443–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karidis Arlene European Versus American Views on Thermal and MBT. Available online: https://www.waste360.com/waste-management-business/european-versus-american-views-on-thermal-and-mechanical-biological-treatments (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Remmas, N.; Manfe, N.; Zerva, I.; Melidis, P.; Raga, R.; Ntougias, S. A Critical Review on the Microbial Ecology of Landfill Leachate Treatment Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Landfill Ordinance, Official Gazette 114/15, 103/18, 4/23. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2023_01_4_68.html (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Council Directive 1999/31/EC of 26 April 1999 on the Landfill of Waste. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1999, 182, 1–19.

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S.M. A Review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Source, Environmental Impact, Effect on Human Health and Remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irto, A.; Crea, F.; Alessandrello, C.; De Stefano, C.; Somma, R.; Zaffino, G.; Zaccaro, S.; Papanikolaou, G.; Cigala, R.M. Landfill Leachate from Municipal Solid Waste: Multi-Technique Approach for Its Fine Characterization and Determination of the Thermodynamic and Sequestering Properties towards Some Toxic Metals. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; AL-Zghoul, T.M.; Al-Qodah, Z. An Extensive Analysis of Combined Processes for Landfill Leachate Treatment. Water 2024, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.A.; Ramli, S.F.; Hung, Y.-T. Physicochemical Technique in Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) Landfill Leachate Remediation: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.N.; Sadaf, S.; Verma, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Kumari, S.; Polisetti, V.; Kallem, P.; Iqbal, J.; Banat, F. Old Landfill Leachate and Municipal Wastewater Co-Treatment by Sequencing Batch Reactor Combined with Coagulation–Flocculation Using Novel Flocculant. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.A.; Jebboe, E.K.; Akiyode, O.O.; Asumana, C.; Nippae, A.; Powoe, M.T.; Sinneh, I.S.; Kesselly, H.F.; Sheriff, S.S.; Thompson-Williams, K.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Waste Management Practices in Liberia: Challenges, Policy Gaps, Health Implications, and Strategic Solutions for Sustainable Development. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiriga, D.; Vestgarden, L.S.; Klempe, H. Groundwater Contamination from a Municipal Landfill: Effect of Age, Landfill Closure, and Season on Groundwater Chemistry. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRN EN 12457-1:2005; Characterization of Waste–Leaching–Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges–Part 1: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 2 L/Kg for Materials with High Solid Content and with Particle Size Below 4 Mm (Without or with Size Reduction) (EN 12457-1:2002). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- HRN EN 12457-2:2005; Characterization of Waste–Leaching–Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges–Part 2: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 10 L/Kg for Materials with Particle Size Below 4 Mm (Without or with Size Reduction) (EN 12457-2:2002). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- WMC Marišćina. Available online: https://www.fzoeu.hr/en/wmc-mariscina/7765 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Marišćina Waste Management Center. Available online: https://www.ekoplus.hr/Foto-12-4-2016.php (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- ASTM D2216-19; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D422-63(2007); Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Analysis of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- ASTM D2974-20e1; Standard Test Methods for Determining the Water (Moisture) Content, Ash Content, and Organic Material of Peat and Other Organic Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ASTM D5550-14; Standard Test Method for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Gas Pycnometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Petrovic, I.; Kaniski, N.; Hrncic, N.; Bosilj, D. Variability in the Solid Particle Density and Its Influence on the Corresponding Void Ratio and Dry Density: A Case Study Conducted on the MBT Reject Waste Stream from the MBT Plant in Marišćina, Croatia. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRN EN 12457-4:2005; Characterization of Waste–Leaching–Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges–Part 4: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 10 L/Kg for Materials with Particle Size Below 10 Mm (Without or with Size Reduction) (EN 12457-4:2002). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- HRN EN ISO 11885:2010; Water Quality–Determination of Selected Elements by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) (ISO 11885:2007; EN ISO 11885:2009). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- HRN EN ISO 12846:2012; Water Quality–Determination of Mercury–Method Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) with and Without Enrichment. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- HRN ISO 15586:2003; Water Quality–Determination of Trace Elements by Atomic Absorption Spectrometry with Graphite Furnace. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- HRN EN 15216:2008; Characterization of Waste–Determination of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) in Water and Eluates (EN 15216:2007). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- Analytical Methods for Atomic Absorption Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Perkin Elmer Instruments LLC: Shelton, CT, USA, 2000.

- DR 5000 Spectrophotometer Manual; Hach Company: Loveland, CO, USA, 2005.

- Petrovic, I.; Kaniski, N.; Hrncic, N.; Hip, I. Correlations between Field Capacity, Porosity, Solid Particle Density and Dry Density of a Mechanically and Biologically (Biodried) Treated Reject Waste Stream. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotvajn, A.Ž.; Tišler, T.; Zagorc-Končan, J. Comparison of Different Treatment Strategies for Industrial Landfill Leachate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesarek, A. The Reliability of Waste Analysis by Conducting a Leaching Test. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Geotechnical Engineering, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, I.; Kaniški, N.; Hrnčić, N.; Bosilj, D. Short- and Long-Term Compressibility Properties of Biologically (Biodried) and Mechanically Treated Municipal Solid Waste: A Case Study of BMT Plant in Marišćina, Croatia. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2024, 15, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Pinedo, M.L.; Riascos, B.D. Presence of Humic Acids in Landfill Leachate and Treatment by Flocculation at Low PH to Reduce High Pollution of This Liquid. Sustainability 2025, 17, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, S.F.; Aziz, H.A.; Omar, F.M.; Yusoff, M.S.; Halim, H.; Kamaruddin, M.A.; Ariffin, K.S.; Hung, Y.T. Reduction of Cod and Highly Coloured Mature Landfill Leachate by Tin Tetrachloride with Rubber Seed and Polyacrylamide. Water 2021, 13, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowczyk, A.; Szymańska-Pulikowska, A. Analysis of the Possibility of Conducting a Comprehensive Assessment of Landfill Leachate Contamination Using Physicochemical Indicators and Toxicity Test. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 221, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likando, N.M.; Dornack, C.; Hamutoko, J.T. Assessing the Physicochemical Parameters of Leachate from Biowaste Fractions in a Laboratory Setting, Using the Elusion Method. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likando, N.M.; Chipandwe, M.S. Statistical Investigation of Climate and Landfill Age Impacts on Kupferberg Landfill Leachate Composition: One-Way ANOVA Analysis. Discov. Water 2024, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, H.; Clark, I. Degradation Pathways of Dissolved Carbon in Landfill Leachate Traced with Compound-Specific 13C Analysis of DOC. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 2008, 44, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickson, O.; Ukundimana, Z.; Wamyil, F.B.; Yusuf, A.A.; Pierre, M.J.; Kagabo, A.S.; Rizinde, T. Quantification and Characterization of Municipal Solid Waste at Aler Dumpsite, Lira City, Uganda: Assessing Pollution Levels and Health Risks. Clean. Waste Syst. 2024, 9, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, P.; Barlaz, M.A.; Rooker, A.P.; Baun, A.; Ledin, A.; Christensen, T.H. Present and Long-Term Composition of MSW Landfill Leachate: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 32, 297–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, J.P.; Ikpe, D.I.; Inam, E.D.; Okon, A.O.; Ebong, G.A.; Benson, N.U. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metals in Landfill Leachates and Impacted Freshwater Ecosystem: An Environmental and Human Health Threat. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Beinabaj, S.M.; Heydariyan, H.; Mohammad Aleii, H.; Hosseinzadeh, A. Concentration of Heavy Metals in Leachate, Soil, and Plants in Tehran’s Landfill: Investigation of the Effect of Landfill Age on the Intensity of Pollution. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baun, A.; Ledin, A.; Reitzel, L.A.; Bjerg, P.L.; Christensen, T.H. Xenobiotic Organic Compounds in Leachates from Ten Danish MSW Landfills—Chemical Analysis and Toxicity Tests. Water Res. 2004, 38, 3845–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Theisen, H.; Vigil, S. Integrated Solid Waste Management: Engineering Principles and Management Issues; McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: Columbus, OH, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780070632370.

- Kumar, S.; Dhar, H.; Nair, V.V.; Bhattacharyya, J.K.; Vaidya, A.N.; Akolkar, A.B. Characterization of Municipal Solid Waste in High-Altitude Sub-Tropical Regions. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idehai, I.; Akujieze, C. Assessment of Some Physiochemical Impacts of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) on Soils: A Case Study of Landfill Areas of Lagos, Nigeria. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 4623–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaghebeur, M.; Laenen, B.; Geysen, D.; Nielsen, P.; Pontikes, Y.; Van Gerven, T.; Spooren, J. Characterization of Landfilled Materials: Screening of the Enhanced Landfill Mining Potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 55, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, C.E.; Scott, J.A.; Natawardaya, H.; Amal, R.; Beydoun, D.; Low, G. Comparison between Acetic Acid and Landfill Leachates for the Leaching of Ph(II), Cd(II), As(V), and Cr(VI) from Clementitious Wastes. Env. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 3977–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method 2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Method 1 | L/S = 2 U1m | L/S = 2 U2m | L/S = 10 U1m | L/S = 10 U2m | L/S = 2 U3r | L/S = 2 U4r | L/S = 10 U3r | L/S = 10 U4r | Max Limit Value [7] |

| TDS (mg/kg) | 43,860 | 8700 | 8250 | 2480 | 2570 | 7700 | 8020 | 2540 | 2420 | 60,000 |

| Cl− (mg/kg) | n.a. | 4190 | 3720 | 400 | 530 | 3560 | 3510 | 540 | 400 | 15,000 |

| F− (mg/kg) | n.a. | 14.6 | 16.3 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 17.7 | 19.0 | 10.3 | 9.9 | 150 |

| SO42− (mg/kg) | n.a. | 2060 | 1940 | 640 | 800 | 1940 | 2120 | 580 | 900 | 20,000 |

| DOC (mg/kg) | 14,200 | 16,710 | 15,920 | 2630 | 2675 | 9393 | 12,939 | 2443 | 2486 | 800 |

| As (mg/kg) | <0.05 | 0.06254 | 0.09083 | 0.02036 | 0.02120 | 0.06203 | 0.07674 | 0.01729 | 0.02379 | 2 |

| Cd (mg/kg) | <0.01 | 0.001607 | 0.000943 | 0.000076 | 0.000141 | 0.002264 | 0.001909 | 0.000193 | 0.000281 | 1 |

| Cr (mg/kg) | 0.74 | 0.447 | 0.375 | 0.139 | 0.072 | 0.288 | 0.495 | 0.078 | 0.067 | 10 |

| Cu (mg/kg) | 1.98 | 0.245 | 0.950 | 0.135 | 0.115 | 0.230 | 0.600 | 0.223 | 0.397 | 50 |

| Ba (mg/kg) | 6.86 | 1.385 | 2.167 | 0.4993 | 0.8972 | 0.9275 | 2.146 | 0.3754 | 0.6301 | 100 |

| Mo (mg/kg) | 0.07 | 0.849 | 0.3975 | 0.4606 | 0.2130 | 0.738 | 0.6394 | 0.3359 | 0.2807 | 10 |

| Ni (mg/kg) | 2.32 | 1.2732 | 0.9361 | 0.3054 | 0.3231 | 0.764 | 1.1786 | 0.4217 | 0.391 | 10 |

| Hg (mg/kg) | 0.00232 | <0.000009 | 0.000281 | 0.000009 | 0.000015 | <0.000009 | 0.000211 | <0.000009 | 0.000105 | 0.2 |

| Pb (mg/kg) | 0.20 | 0.00333 | 0.00827 | 0.00222 | 0.00168 | 0.00312 | 0.01108 | 0.00421 | 0.00377 | 10 |

| Zn (mg/kg) | 14.30 | 12.12 | 11.04 | 1.89 | 2.33 | 5.78 | 9.42 | 2.71 | 2.90 | 50 |

| Sb (mg/kg) | <0.03 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.7 |

| Se (mg/kg) | <0.01 | 0.003554 | 0.003195 | <0.00005 | <0.00005 | 0.00314 | 0.002815 | <0.0005 | <0.00005 | 0.51 |

| L/S = 2 U1 | L/S = 2 U2 | L/S = 2 U3 | L/S = 2 U4 | L/S = 10 U1 | L/S = 10 U2 | L/S = 10 U3 | L/S = 10 U4 | |

| L/S = 2 U1 | 1.00000 | |||||||

| L/S = 2 U2 | 0.99986 | 1.00000 | ||||||

| L/S = 2 U3 | 0.99022 | 0.98806 | 1.00000 | |||||

| L/S = 2 U4 | 0.99907 | 0.99860 | 0.99437 | 1.00000 | ||||

| L/S = 10 U1 | 0.98733 | 0.98878 | 0.97492 | 0.98934 | 1.00000 | |||

| L/S = 10 U2 | 0.98320 | 0.98389 | 0.97976 | 0.98800 | 0.99775 | 1.00000 | ||

| L/S = 10 U3 | 0.99406 | 0.99465 | 0.98595 | 0.99606 | 0.99827 | 0.99703 | 1.00000 | |

| L/S = 10 U4 | 0.97190 | 0.97336 | 0.96575 | 0.97729 | 0.99598 | 0.99810 | 0.99174 | 1.00000 |

| TDS | Cl− | F− | SO42− | DOC | As | Cd | Cr | Cu | Ba | Mo | Ni | Hg | Pb | Zn | Se | |

| TDS | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| Cl− | −0.183 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| F− | −0.637 | 0.827 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| SO42− | −0.387 | 0.963 | 0.927 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| DOC | 0.511 | 0.713 | 0.231 | 0.539 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| As | −0.303 | 0.939 | 0.882 | 0.954 | 0.611 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Cd | −0.162 | 0.900 | 0.814 | 0.897 | 0.543 | 0.797 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Cr | 0.832 | 0.338 | −0.152 | 0.143 | 0.860 | 0.214 | 0.300 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Cu | 0.927 | −0.145 | −0.547 | −0.318 | 0.544 | −0.148 | −0.206 | 0.799 | 1.000 | |||||||

| Ba | 0.980 | −0.135 | −0.576 | −0.323 | 0.567 | −0.206 | −0.154 | 0.863 | 0.964 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Mo | −0.392 | 0.829 | 0.795 | 0.835 | 0.379 | 0.688 | 0.860 | 0.079 | −0.494 | −0.420 | 1.000 | |||||

| Ni | 0.921 | 0.164 | −0.351 | −0.044 | 0.773 | 0.016 | 0.140 | 0.969 | 0.864 | 0.929 | −0.082 | 1.000 | ||||

| Hg | 0.980 | −0.339 | −0.730 | −0.517 | 0.383 | −0.407 | −0.322 | 0.744 | 0.947 | 0.973 | −0.555 | 0.850 | 1.000 | |||

| Pb | 0.981 | −0.369 | −0.759 | −0.552 | 0.346 | −0.463 | −0.330 | 0.725 | 0.913 | 0.957 | −0.539 | 0.841 | 0.995 | 1.000 | ||

| Zn | 0.724 | 0.478 | −0.054 | 0.280 | 0.954 | 0.363 | 0.330 | 0.944 | 0.740 | 0.768 | 0.142 | 0.916 | 0.625 | 0.594 | 1.000 | |

| Se | −0.102 | 0.995 | 0.782 | 0.940 | 0.757 | 0.924 | 0.900 | 0.402 | −0.070 | −0.060 | 0.808 | 0.234 | −0.262 | −0.292 | 0.535 | 1.000 |

| Sample | 1 (6 Days) | 2 (9 Days) | Sample | 1 (6 Days) | 2 (9 Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 4.95 | 5.00 | Al (mg/kg) | 15.22 | 30.76 |

| EC (mS/cm) | 28 | 37.2 | As (mg/kg) | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| TDS (mg/kg) | 13,990 | 18,610 | Cd (mg/kg) | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| salinity (‰) | 17.2 | 23.5 | Cr (mg/kg) | 1.87 | 1.81 |

| SO42− (mg/L) | 2000 | 3900 | Cu (mg/kg) | 4.79 | 7.02 |

| Cl− (mg/L) | 4900 | 8400 | Fe (mg/kg) | 199.16 | 93.67 |

| PO43− (mg/L) | 134 | 233 | Mn (mg/kg) | 149.16 | 169.19 |

| Br2 (mg/L) | <0.02 | 26 | Ni (mg/kg) | 9.58 | 84.90 |

| NO3− (mg/L) | 30 | 50 | Hg (mg/kg) | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| F− (mg/L) | 95 | 117 | Pb (mg/kg) | 0.47 | 6.72 |

| DOC (mg/L) | 25,400 | 28,200 | Zn (mg/kg) | 41.61 | 45.89 |

| TOC (mg/L) | 32,800 | 35,410 | |||

| TN (mg/L) | 296.7 | 687.9 | |||

| BOD5 (mg/L) | 575 | 1021.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ptiček Siročić, A.; Dogančić, D.; Petrović, I.; Hrnčić, N. Leachate Analysis of Biodried MSW: Case Study of the CWMC Marišćina. Processes 2026, 14, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010141

Ptiček Siročić A, Dogančić D, Petrović I, Hrnčić N. Leachate Analysis of Biodried MSW: Case Study of the CWMC Marišćina. Processes. 2026; 14(1):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010141

Chicago/Turabian StylePtiček Siročić, Anita, Dragana Dogančić, Igor Petrović, and Nikola Hrnčić. 2026. "Leachate Analysis of Biodried MSW: Case Study of the CWMC Marišćina" Processes 14, no. 1: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010141

APA StylePtiček Siročić, A., Dogančić, D., Petrović, I., & Hrnčić, N. (2026). Leachate Analysis of Biodried MSW: Case Study of the CWMC Marišćina. Processes, 14(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010141