Production Dynamics of Hydraulic Fractured Horizontal Wells in Shale Gas Reservoirs Based on Fractal Fracture Networks and the EDFM

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

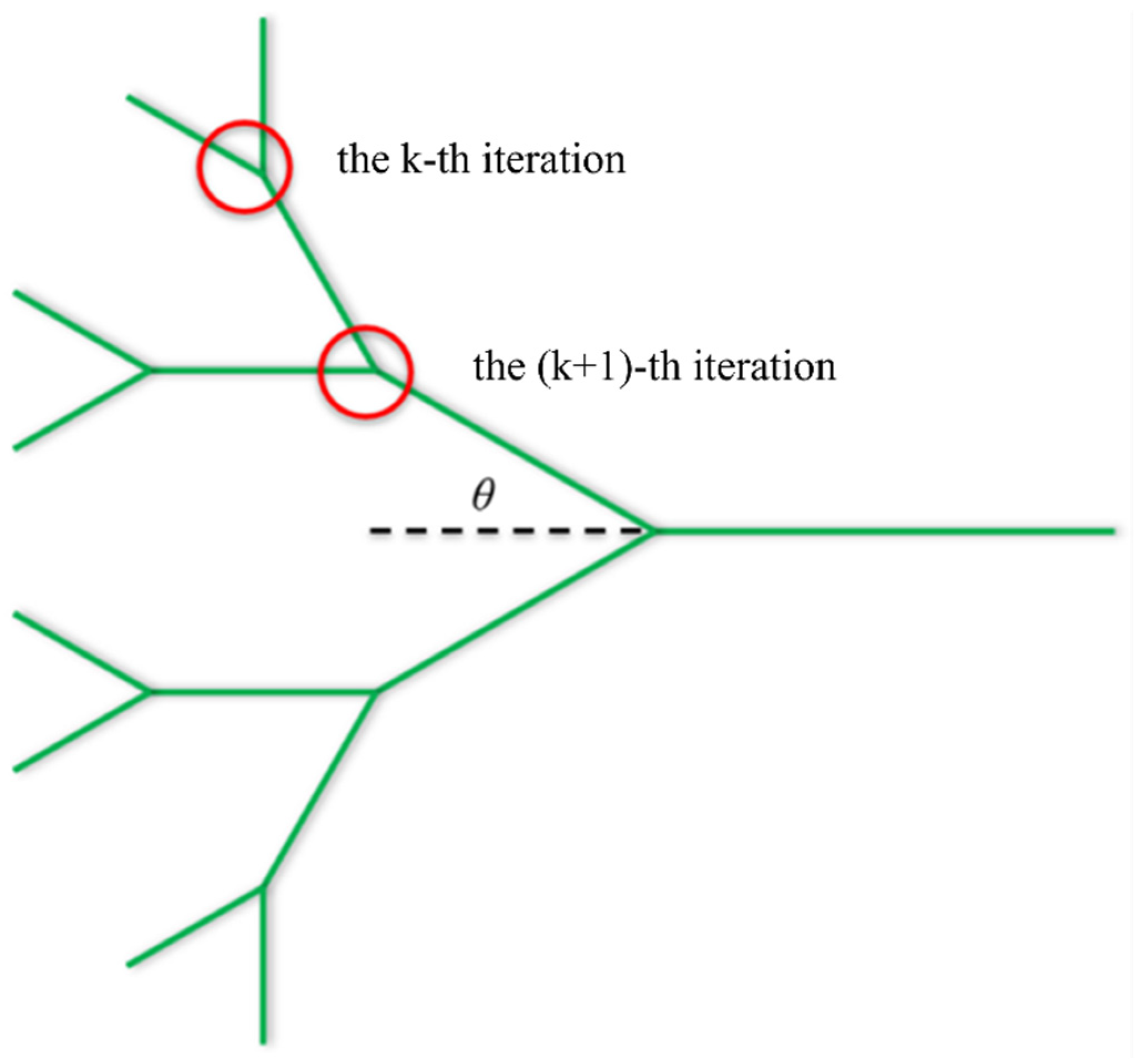

2.1. Fractal Fracture Model

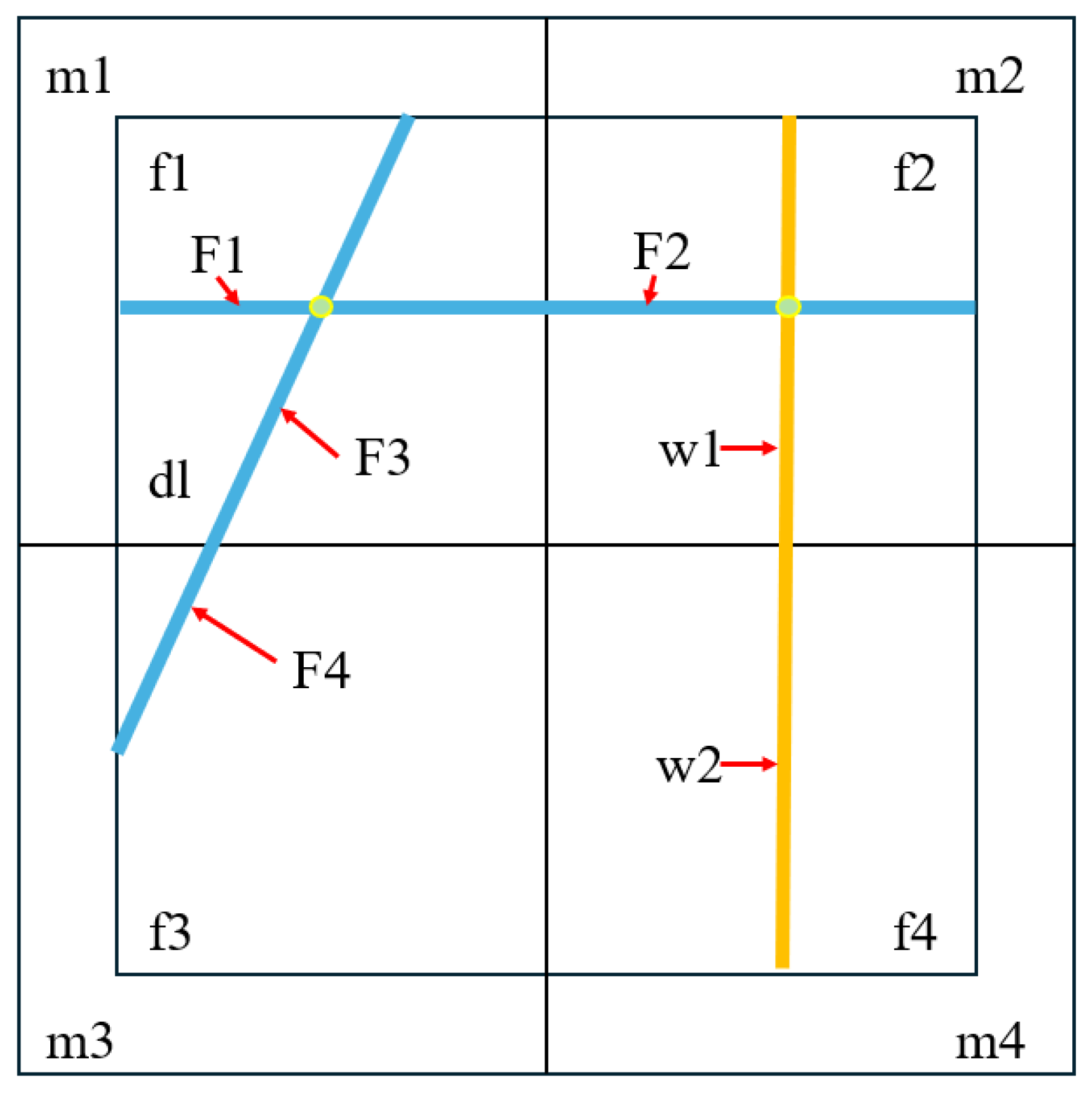

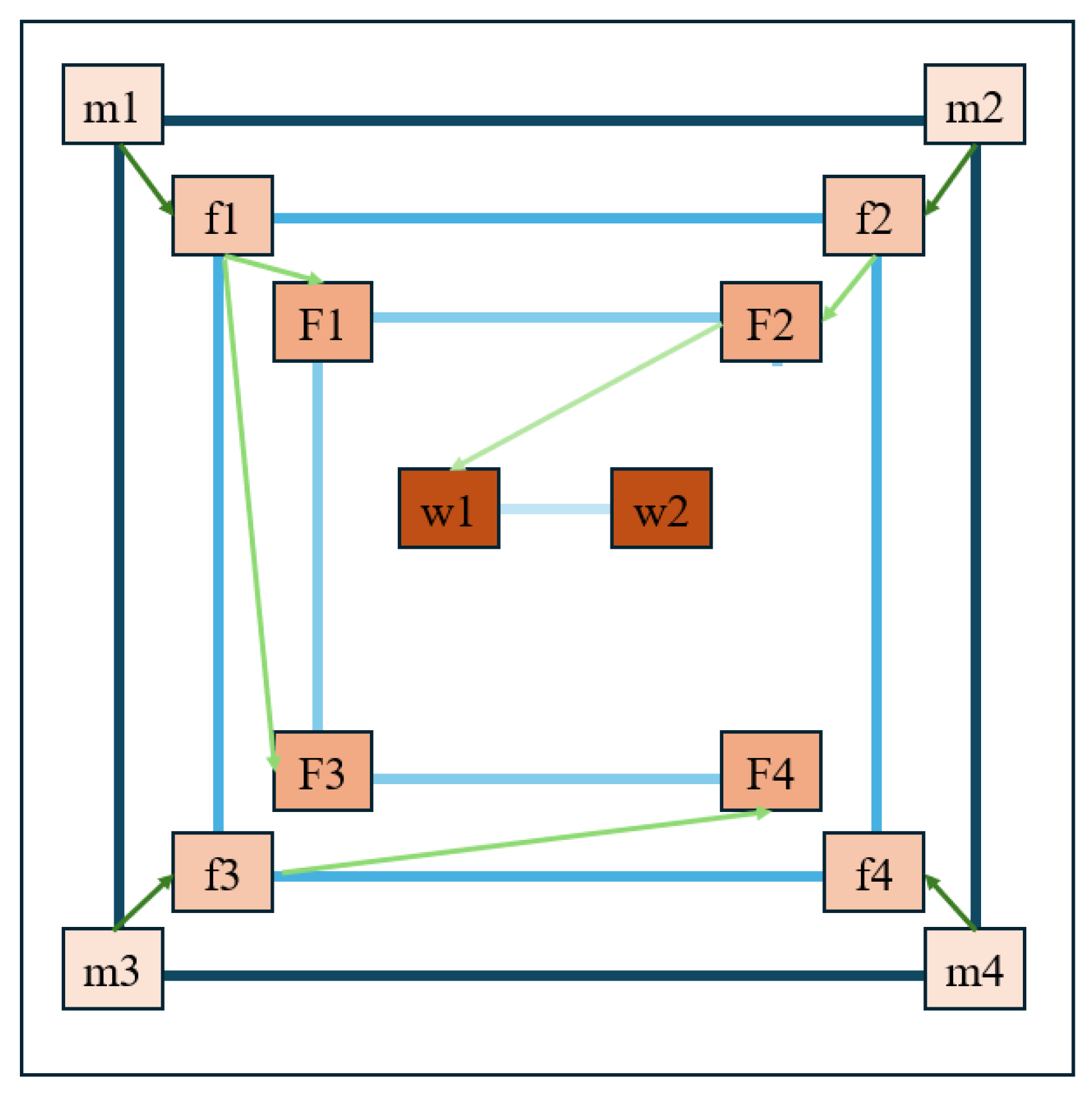

2.2. Embedded Discrete Fracture Model

2.2.1. Model Construction and Basic Assumptions

- The reservoir temperature is constant, and the flow process is isothermal.

- The effects of CO2 dissolution, residual trapping, and geochemical reactions within the reservoir are neglected.

- Supercritical CO2 is treated as a gaseous component with high density and low viscosity.

- Discrete fractures possess heterogeneous properties such as aperture, length, azimuth, and effective height, exhibiting irregular spatial distribution.

2.2.2. Treatment of Non-Neighboring Connections (NNCs)

- Type I NNC: connections between fracture grids and intersected microfracture grids, such as those between f1 and F1, and between f3 and F4;

- Type II NNC: connections between non-adjacent fracture grids belonging to the same discrete fracture after subdivision by the structured grid, such as between F1 and F2, and between F3 and F4;

- Type III NNC: connections between intersecting discrete fractures, such as between F1 and F3;

- Type IV NNC: connections between fractures and the wellbore, such as between F2 and w1.

2.2.3. Fully Implicit Numerical Model

3. Results and Discussion

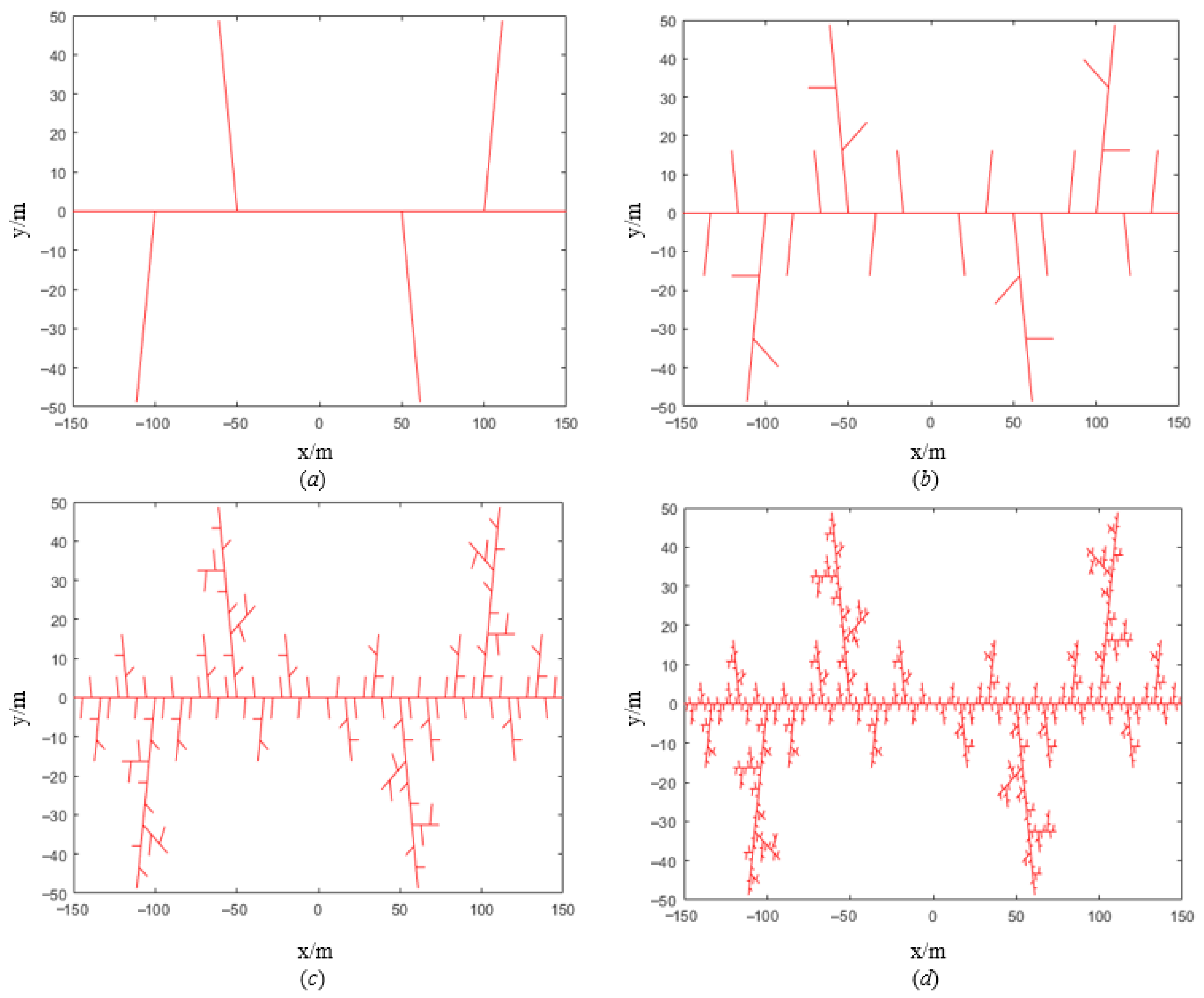

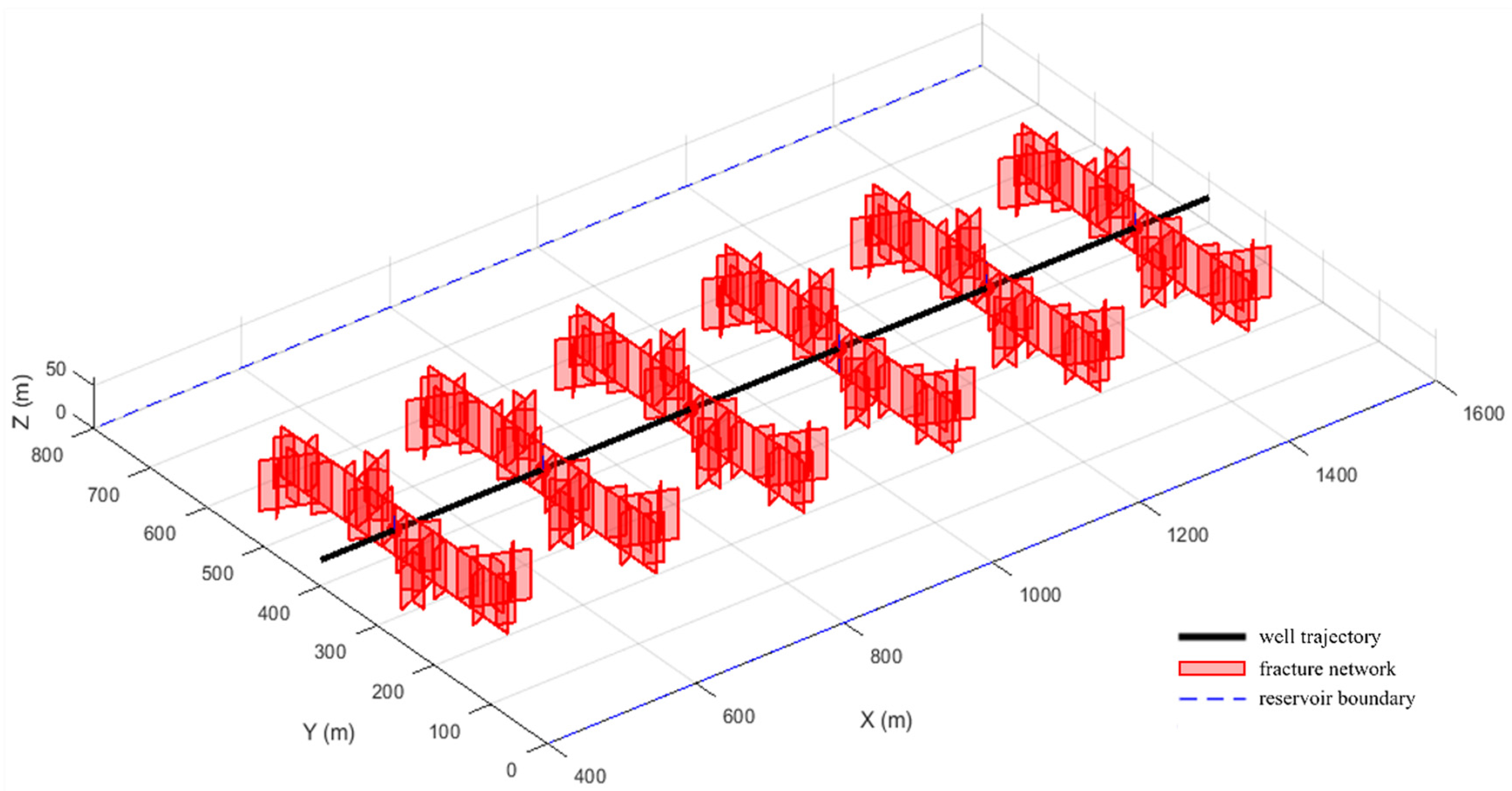

3.1. Fractured Horizontal Well Model with a Fractal Fracture Network

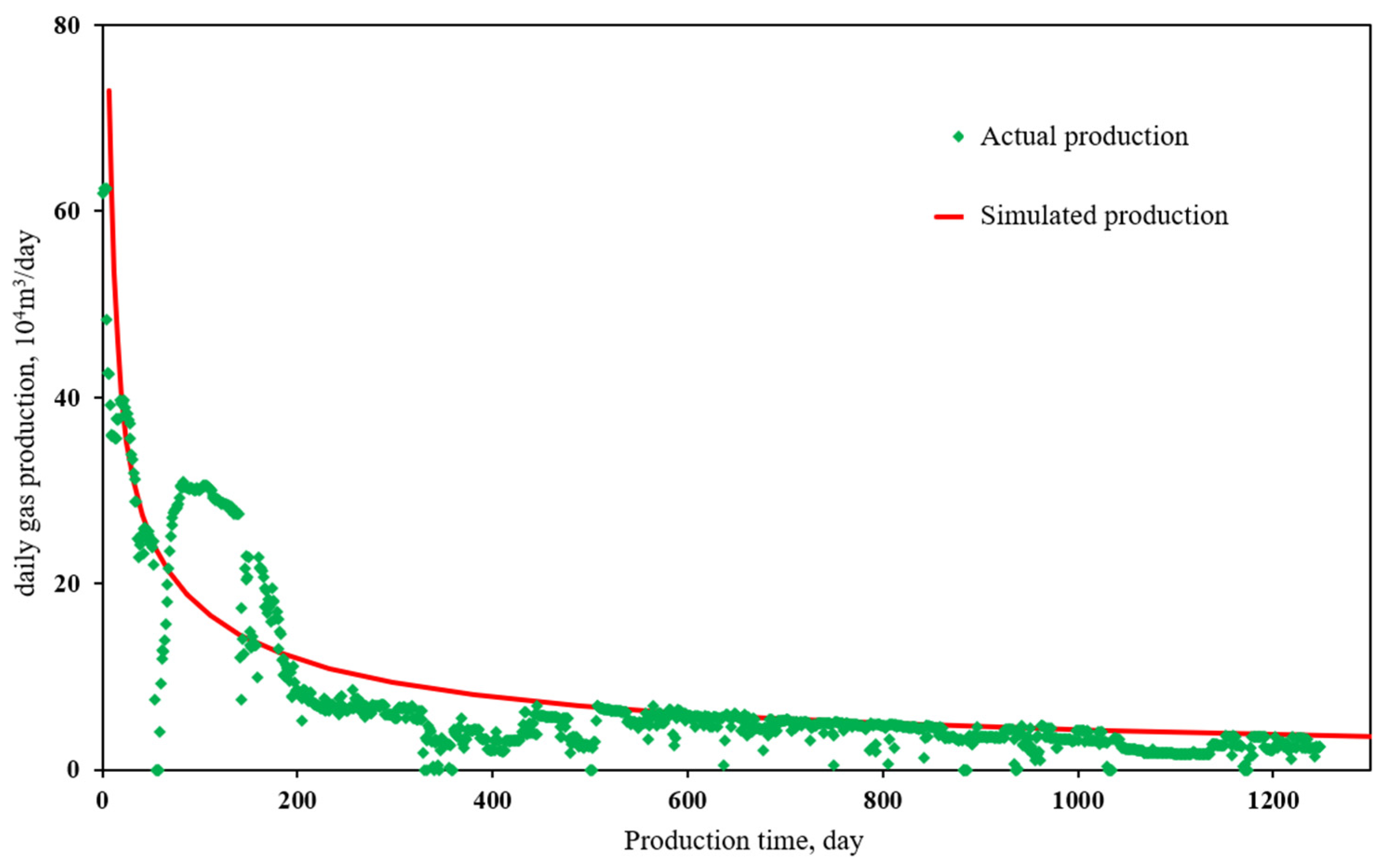

3.2. Model Verification

3.3. Production Dynamics Analysis of Fractured Horizontal Wells

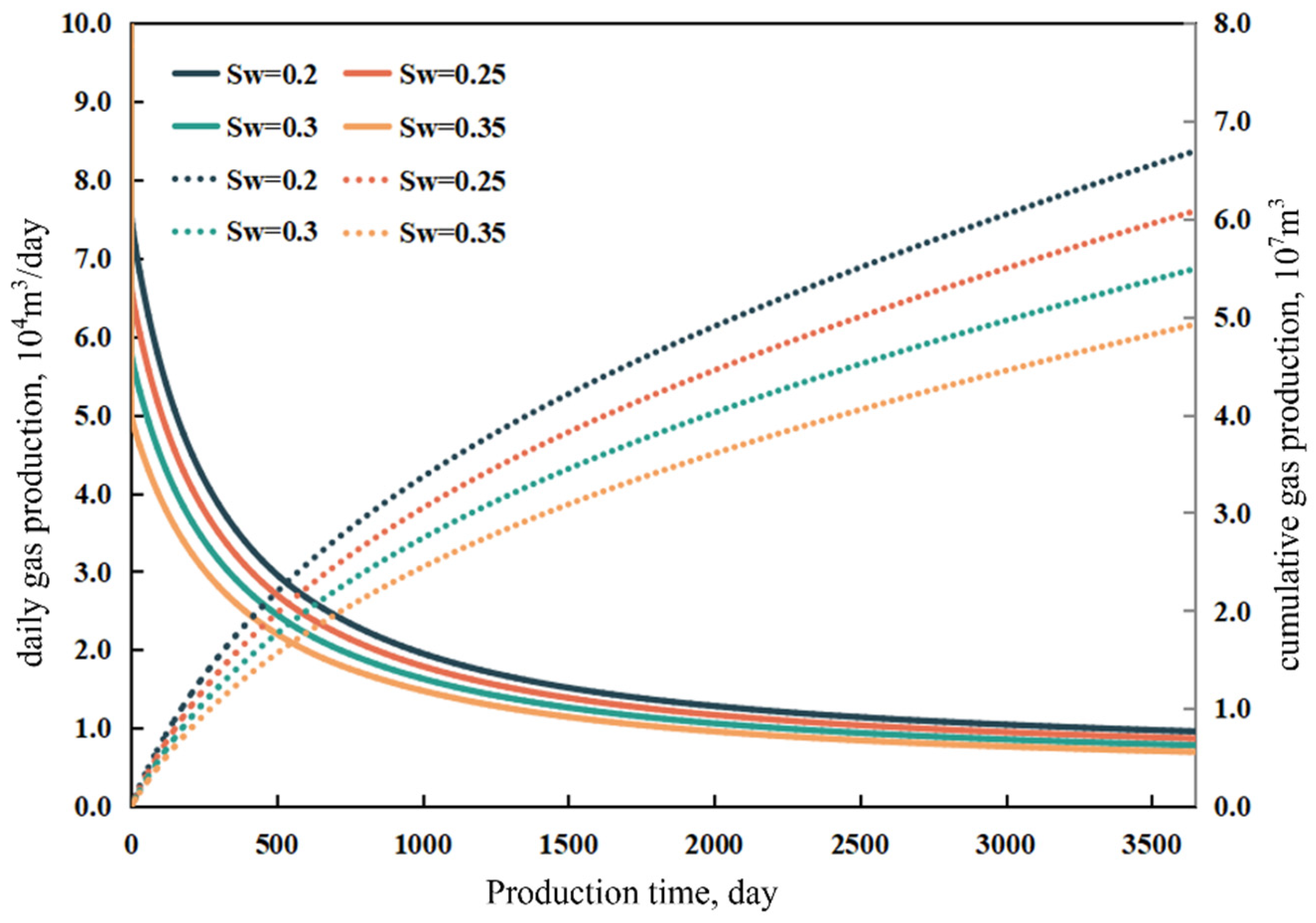

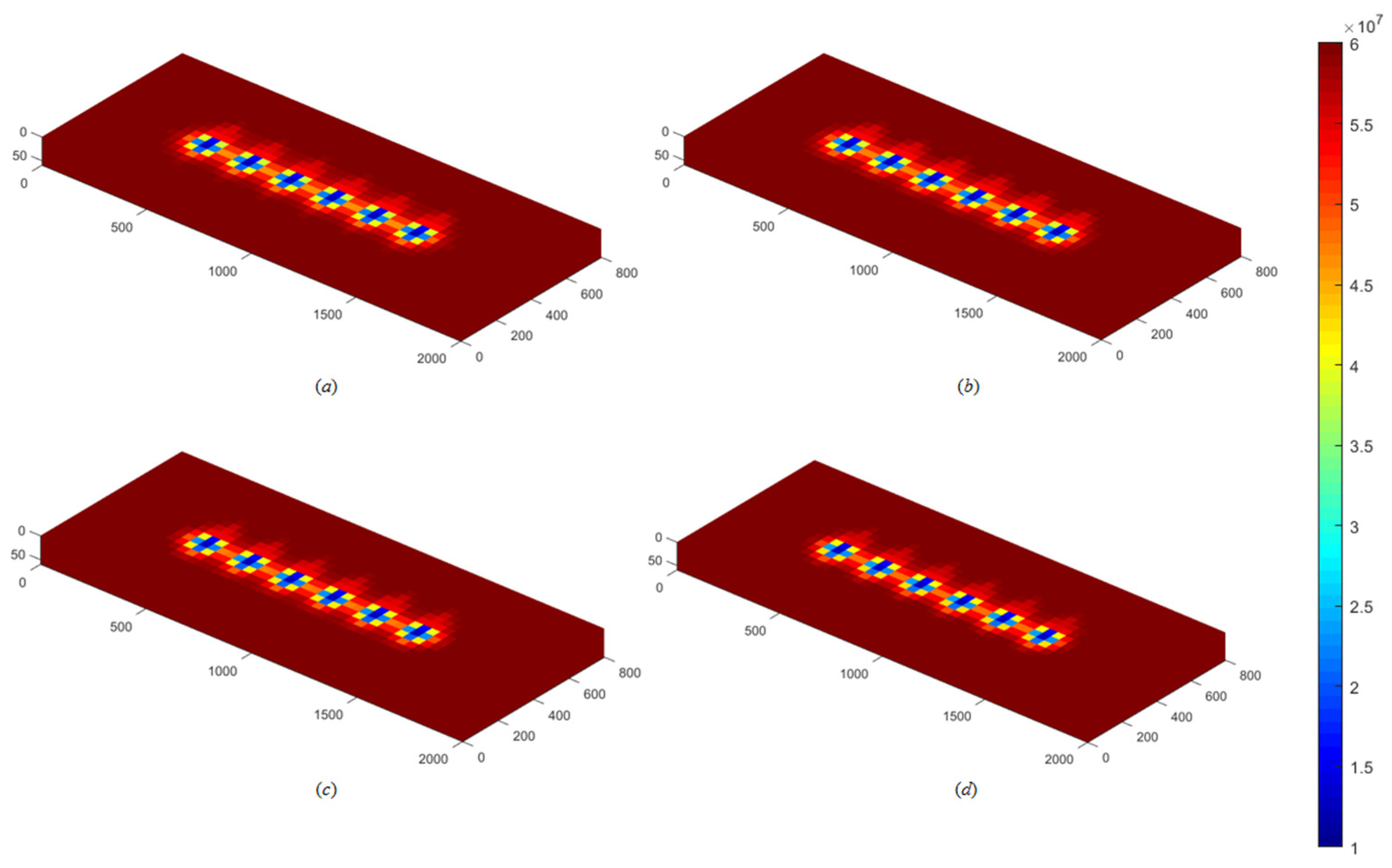

3.3.1. Influence of Initial Water Saturation

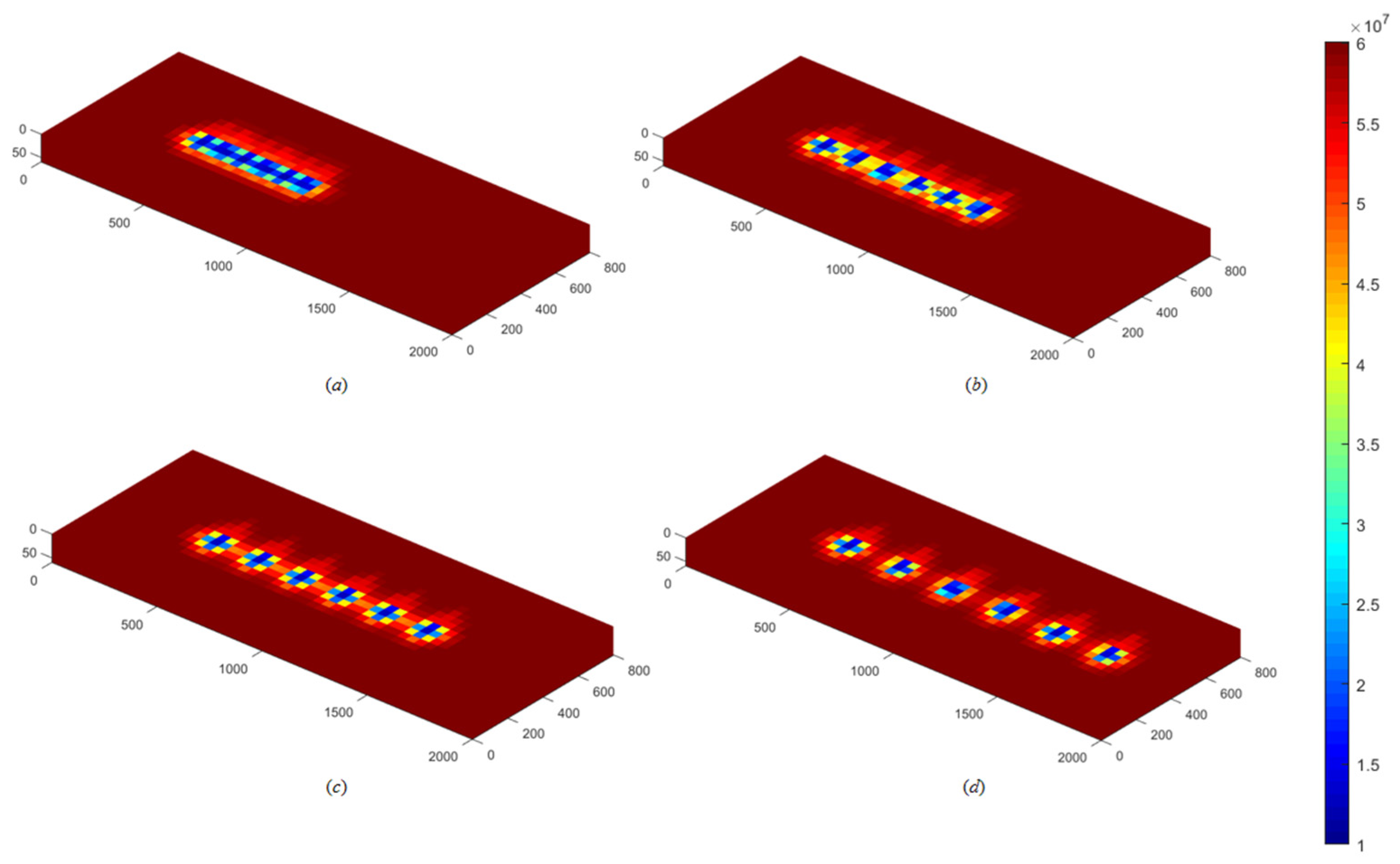

3.3.2. Influence of Hydraulic Fracture Spacing

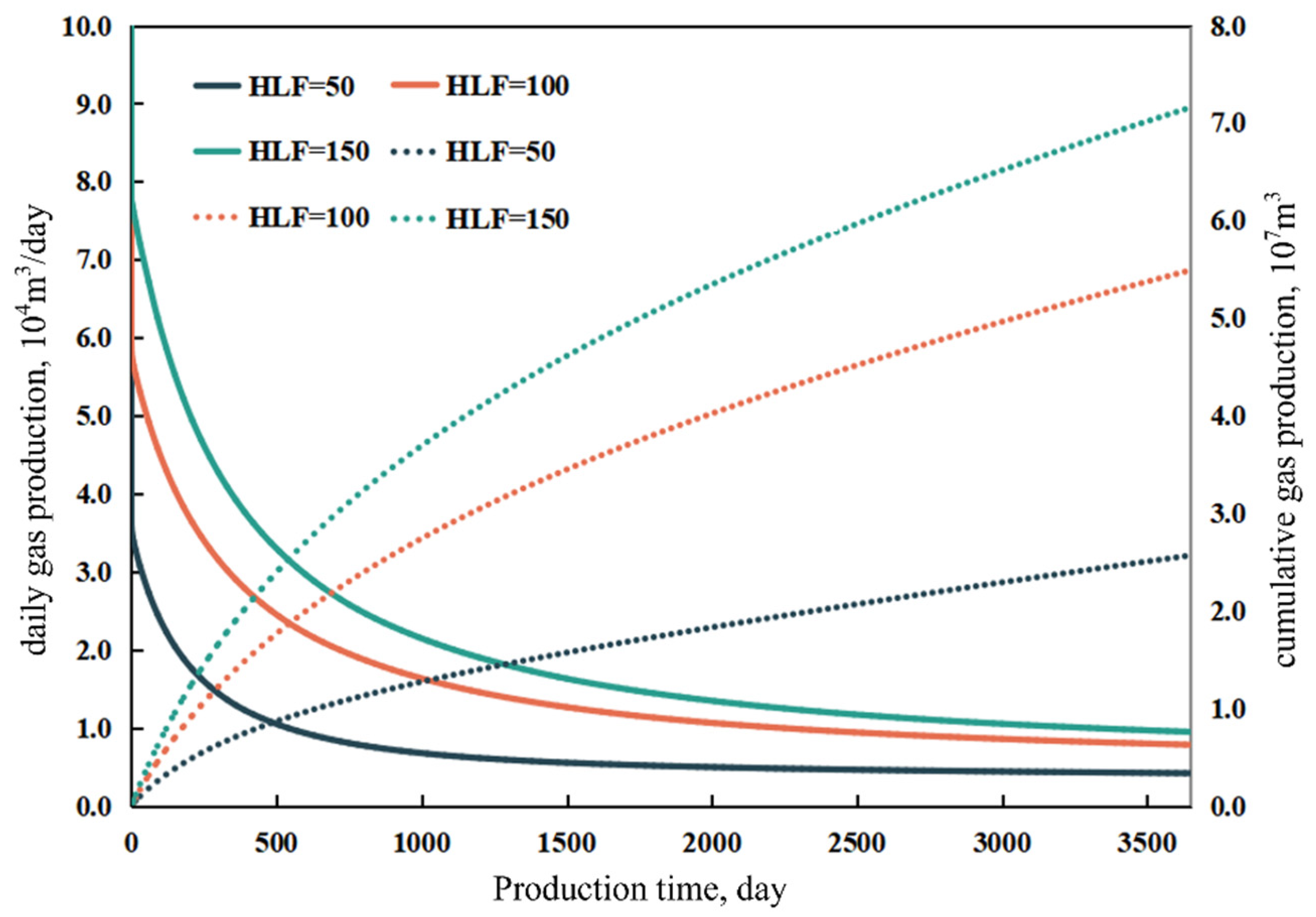

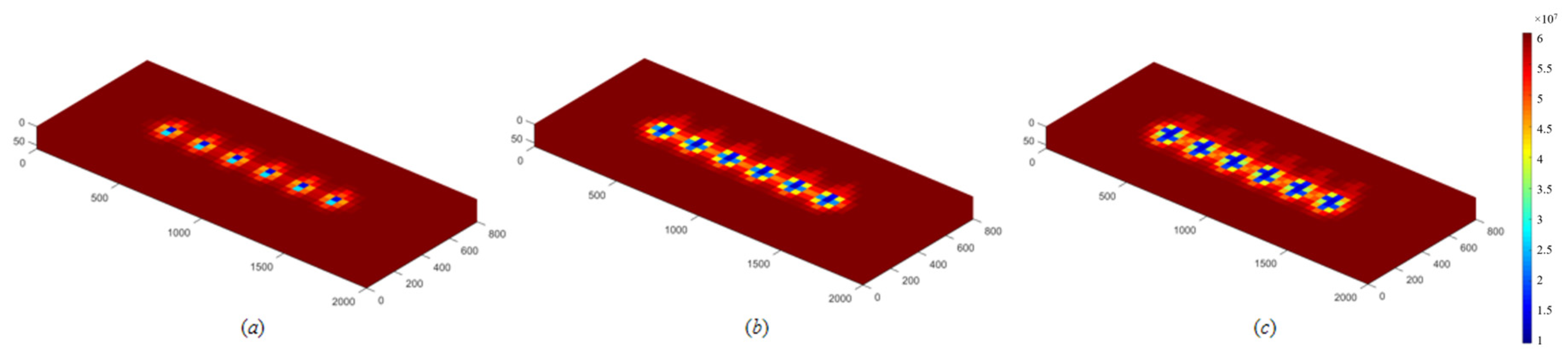

3.3.3. Influence of Hydraulic Fracture Half-Length

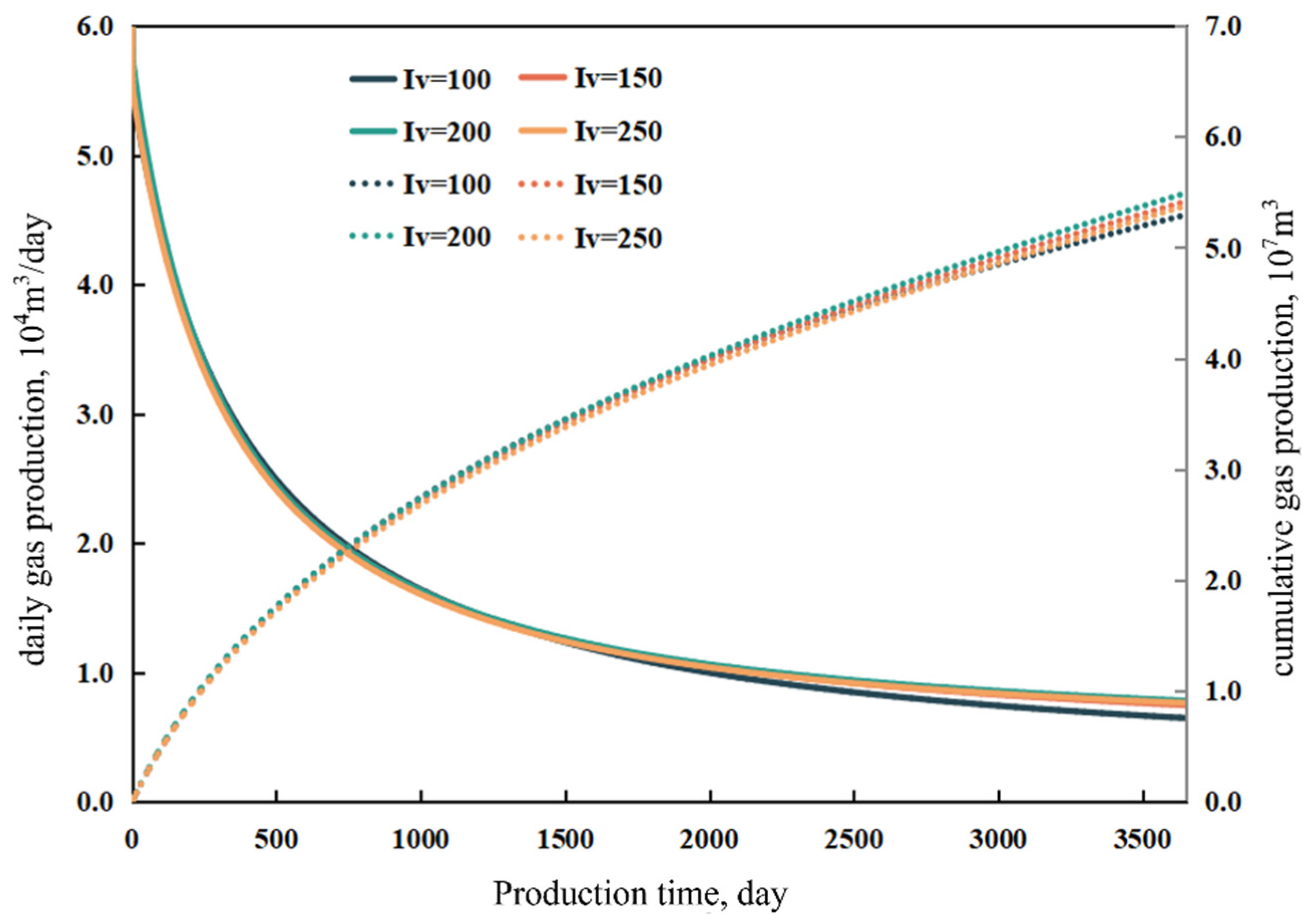

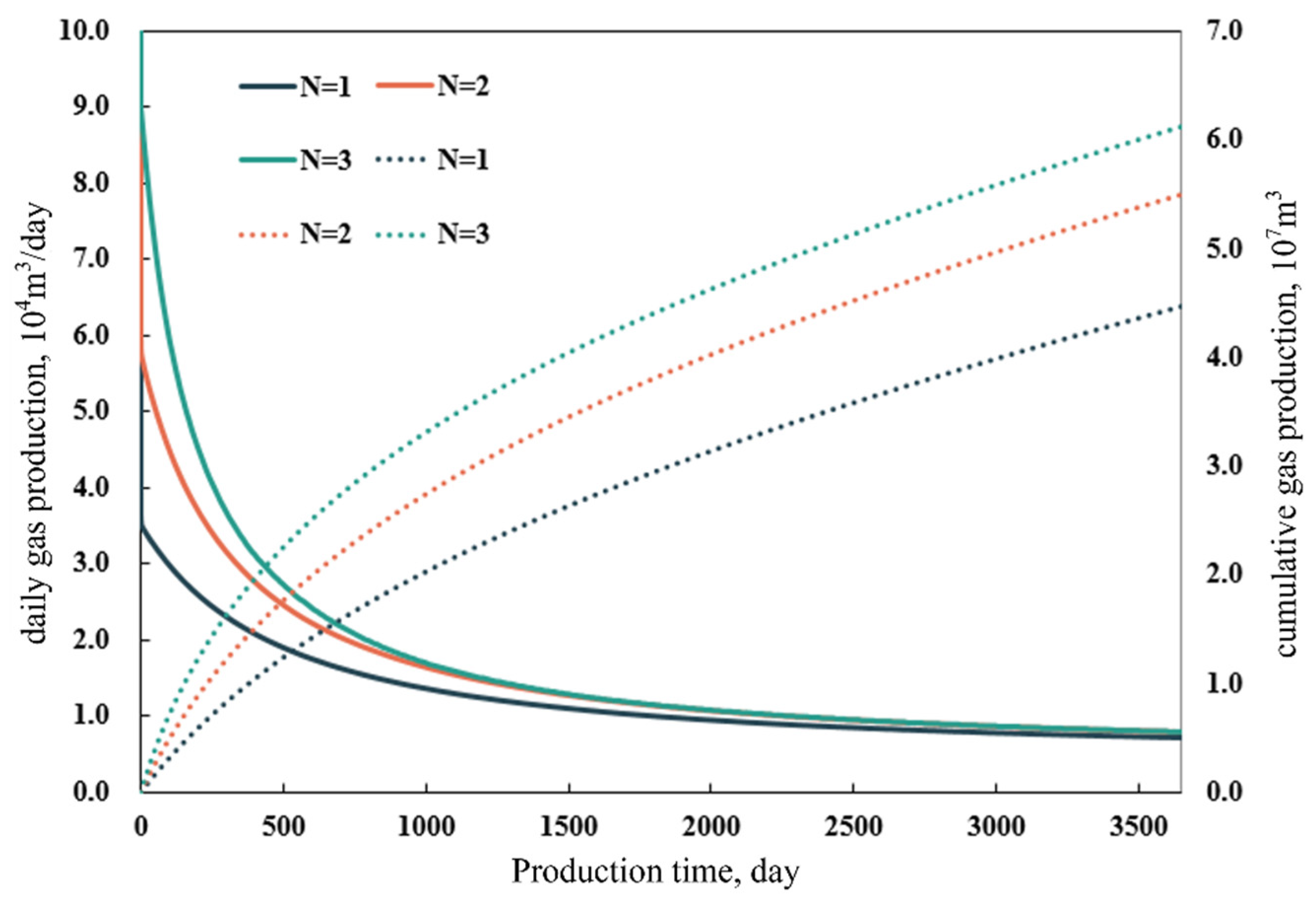

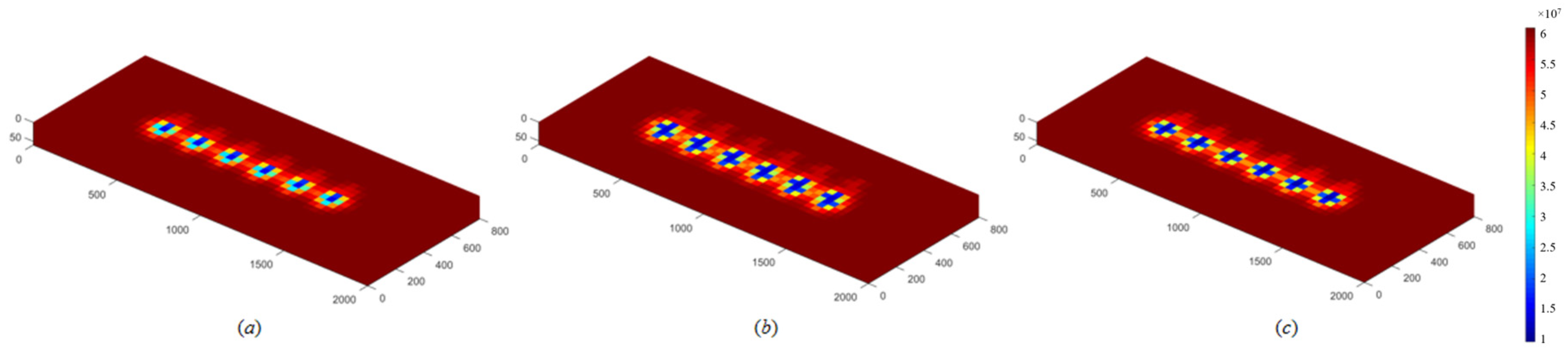

3.3.4. Influence of Fracture Iteration Number

3.4. Model Limitations

- The model does not account for stress-dependent fracture closure or aperture reduction. In reality, fracture conductivity may decrease over time due to increasing effective stress, which could modify long-term production behavior.

- Fracture permeability, aperture, and connectivity are assumed to remain constant throughout the simulation. Potential dynamic evolution of fracture properties—such as proppant embedment, deformation, or shear dilation—is not included. This simplification is commonly adopted in field-scale EDFM simulations because long-term production is governed primarily by reservoir drainage behavior rather than small late-time variations in fracture deformation. While the present fractal algorithm describes static fracture geometry, it could, in principle, be coupled with geomechanical models to simulate dynamic fracture propagation under evolving stress fields.

- The simulations assume constant reservoir temperature. Thermal effects, such as temperature-dependent gas properties or thermoelastic responses, are neglected.

- The fine-scale fractal–EDFM is constructed at high resolution only within the near-well drainage region to capture detailed fracture interactions. For multiwell, field-scale simulations—where such resolution is computationally infeasible—the detailed fractal geometry can be retained locally, whereas the far-field reservoir is represented using a coarse dual-porosity/dual-permeability model with effective properties calibrated from the fine-scale results. This hybrid strategy preserves the key drainage behavior while maintaining computational tractability.

4. Conclusions

- The fractal fracture model accurately characterizes the heterogeneity of fracture networks. By adjusting key parameters such as the iteration number (N), branching number (c), scale factor (γ), and deviation angle (θ), the model captures the self-similar features of fracture geometry and spatial statistics, providing a robust theoretical framework for modeling complex hydraulic fracture networks.

- The EDFM exhibits significant advantages in simulating multiscale fracture–matrix interactions. By employing the Non-Neighboring Connection (NNC) mechanism to describe inter-domain fluid exchange, the EDFM effectively represents irregular fracture geometries without local grid refinement, thereby enhancing computational efficiency, numerical stability, and accuracy.

- Reservoir and fracturing parameters exert strong influences on production dynamics. When the initial water saturation increases to 0.35, the capillary retention effect causes a 26.4% decline in cumulative gas production compared with the base case (Sw = 0.20). An optimal fracture spacing of 200 m effectively mitigates inter-well interference, improving cumulative gas production by 3.71% relative to the 100 m case. Increasing the hydraulic fracture half-length markedly enhances gas well productivity, yielding higher initial rates and sustained production plateaus. Moreover, increasing the iteration number (N) significantly alters the flow field characteristics—manifested as higher early-time production, greater near-wellbore pressure drops, and an expanded pressure disturbance range.

- The proposed fractal–EDFM coupled approach demonstrates strong engineering applicability. It provides a theoretical and technical basis for optimizing fracture network parameters and designing field development strategies, offering reliable support for the efficient exploitation of shale gas reservoirs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Wang, B.; Hu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hu, A. Development of China’s natural gas: Review 2023 and outlook 2024. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lei, Z.; Dong, W.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X.; Tan, J. Progress, challenges and prospects of unconventional oil and gas development of CNPC. China Pet. Explor. 2022, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Ge, M.; Zhao, P.; Guo, T.; Gao, B.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Lin, T.; Yuan, K.; Li, F. Status-quo, potential, and recommendations on shale gas exploration and exploitation in China. Oil Gas Geol. 2025, 46, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zuo, L.; Yin, D.; Jiang, T.; Duan, H.; Wang, H. Fracturing technology development status and high efficiency fracturing technology on normal hydrostatic pressure shale gas. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2023, 41, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, T. Global shale gas development practice and suggestions for China in promoting shale gas industrialization. Mod. Chem. Ind. 2022, 42, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M.; Liao, X.W.; Zhao, X.L.; Lv, S.; Zhu, L. A semianalytical approach for obtaining type curves of multiple-fractured horizontal wells with secondary-fracture networks. SPE J. 2016, 21, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Takahashi, H. Parametric study of the energy extraction from hot dry rock based on fractal fracture network model. Geothermics 1995, 24, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P. Transport Characteristics of Dendritic Fractal Branching Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, S.; Ge, H. A new method for evaluating ability of forming fracture network in shale reservoir. Rock Soil Mech. 2013, 34, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Cong, L. Stochastic fractal model for fracture network parameter inversion of fracturing horizontal well. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2019, 26, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Su, Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, Y. Application of the fractal geometry theory on fracture network simulation. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2017, 7, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragón-Nava, H.; Samayoa, D.; Mena, B.; Balankin, A.S. Fractal Features of Fracture Networks and Key Attributes of Their Models. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lough, M.F.; Jensen, C.L. Hierarchical modeling of flow in naturally fractured formations with multiple length scales. Water Resour. Res. 2001, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lee, S.H. Efficient field-scale simulation of black oil in a naturally fractured reservoir through discrete fracture networks and homogenized media. SPE Res. Eval. Eng. 2008, 11, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominelli, A.; Panfili, P.; Scotti, A. Using embedded discrete fracture models (EDFMs) to simulate realistic fluid flow problems. In Proceedings of the Second EAGE Workshop Naturally Fractured Reservoirs: Naturally Fractured Reservoirs in Real Life, Muscat, Oman, 8–11 December 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinfar, A.; Varavei, A.; Sepehrnoori, K.; Johns, R.T. Development of a coupled dual continuum and discrete fracture model for the simulation of unconventional reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Simulation Symposium, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 18–20 February 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinfar, A.; Varavei, A.; Sepehrnoori, K.; Johns, R.T. Development of an efficient embedded discrete fracture model for 3D compositional reservoir simulation in fractured reservoirs. SPE J. 2014, 19, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakiba, M.; Sepehrnoori, K. Using embedded discrete fracture model (EDFM) and microseismic monitoring data to characterize the complex hydraulic fracture networks. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 28–30 September 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Yan, B.; Killough, J.E.; Wang, Y. An efficient method for fractured shale reservoir history matching: The embedded discrete fracture multi-continuum approach. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 26–28 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Jiang, J.; Younis, R.M. Fully-coupled XFEM-EDFM hybrid model for geomechanics and flow in fractured reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Simulation Conference, Montgomery, TX, USA, 20–22 February 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, B.; Chen, B. A hybrid embedded discrete fracture model for simulating tight porous media with complex fracture systems. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Sepehrnoori, K. Development of an embedded discrete fracture model for field-scale reservoir simulation with complex corner-point grids. SPE J. 2019, 24, 1552–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, M.; Su, S.; Yao, Z.; Liu, L. Numerical Simulation of a Horizontal Well With Multi-Stage Oval Hydraulic Fractures in Tight Oil Reservoir Based on an Embedded Discrete Fracture Model. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 601107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Onishi, T.; Chen, H.; Datta-Gupta, A. Parameterization of embedded discrete fracture models (EDFM) for efficient history matching of fractured reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sheng, J.J. An efficient embedded discrete fracture model based on the unstructured quadrangular grid. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 85, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Sepehrnoori, K. Modeling fracture transient flow using the embedded discrete fracture model with nested local grid refinement. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 218, 110882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Du, X.; Rao, X.; Renyi, C.; Pin, J. A numerical simulation approach for embedded discrete fracture model coupled green element method based on two sets of nodes. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2022, 54, 2892–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.-S. Thermal-hydraulic-mechanical analysis of enhanced geothermal reservoirs with hybrid fracture patterns using a combined XFEM and EDFM-MINC model. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 228, 211984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.P.; Zhen, R.C.; Xu, Y.J.; Wang, S.; Ao, X.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J. A numerical pressure transient model of fractured well with complex fractures of tight gas reservoirs considering gas–water two phase by EDFM. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 231, 212286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losapio, D.; Scotti, A. Local embedded discrete fracture model (LEDFM). Adv. Water Resour. 2023, 171, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ge, F.; Yang, Z.D.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, D.X.; Tian, Y. Capacity of compact reservoir based on dual medium embedded discrete crack model. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 10780–10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Shi, J.; Jia, Z.; Cao, C.; Cheng, L.; Liu, G. A modified 3D-EDFM method considering fracture width variation due to thermal stress and its application in enhanced geothermal system. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tene, M.; Bosma, S.B.M.; Al Kobaisi, M.S.; Hajibeygi, H. Projection-based Embedded Discrete Fracture Model (pEDFM). Adv. Water Resour. 2017, 105, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, S.; Dentz, M.; Cueto-Felgueroso, E. Anomalous Pressure Diffusion and Deformation in Two- and Three-Dimensional Heterogeneous Fractured Media. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berre, I.; Doster, F.; Keilegavlen, E. Flow in Fractured Porous Media: A Review of Conceptual Models and Discretization Approaches. Transp. Porous Media 2019, 130, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Su, Y.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W. CO2 huff and puff simulation in horizontal well with random fractal volume fracturing. Lithol. Reserv. 2020, 32, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaziane, B.; Jurak, M.; Radišić, I. Convergence of a finite volume scheme for immiscible compressible two-phase flow in porous media by the concept of the global pressure. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 399, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.D.; Hammond, G.E.; Valocchi, A.J.; LaForce, T. Linear and nonlinear solvers for simulating multiphase flow within large-scale engineered subsurface systems. Adv. Water Resour. 2021, 156, 104029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial reservoir pressure, pi, MPa | 60 | Formation temperature, T, K | 353.15 |

| Reservoir thickness, h, m | 90 | Grid step size, x × y × z, m | 40 × 40 × 3 |

| Matrix permeability, kom, mD | 1.6 × 10−4 | Initial water saturation, Sf0 | 0.35 |

| Matrix porosity, ϕom | 0.07 | Wellbore radius, rw, m | 0.1 |

| Iteration number, N | 3 | Fractal branch number, c | 3 |

| Scale factor, γ | 0.6 | Deviation angle, θ | 30 |

| Hydraulic fracture permeability, kF, mD | 200 | Hydraulic fracture aperture, wF, m | 0.002 |

| Microfracture permeability, kf, mD | 0.001 | Well constraint, BHP, MPa | 35 |

| Component | Content |

|---|---|

| Methane (CH4) | 84.4% |

| Nitrogen (N2) | 2% |

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 10% |

| Light hydrocarbons (C2–C5) | 3% |

| Intermediate hydrocarbons (C6–C10) | 0.5% |

| Heavy hydrocarbons (C11+) | 0.1% |

| Initial Water Saturation | Cumulative Gas Production (107 m3) | CH4 (107 m3) | N2 (106 m3) | CO2 (107 m3) | C2–C5 (106 m3) | C6–C10 (106 m3) | C11+ (105 m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 6.693 | 3.835 | 1.587 | 1.247 | 4.420 | 1.458 | 6.227 |

| 0.25 | 6.080 | 3.484 | 1.442 | 1.132 | 4.016 | 1.324 | 5.713 |

| 0.3 | 5.491 | 3.146 | 1.302 | 1.023 | 3.626 | 1.196 | 5.209 |

| 0.35 | 4.923 | 2.821 | 1.167 | 0.917 | 3.251 | 1.072 | 4.715 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, H.; Chen, M.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; He, S.; Zhang, R. Production Dynamics of Hydraulic Fractured Horizontal Wells in Shale Gas Reservoirs Based on Fractal Fracture Networks and the EDFM. Processes 2026, 14, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010114

Xiao H, Chen M, Li S, Yang J, He S, Zhang R. Production Dynamics of Hydraulic Fractured Horizontal Wells in Shale Gas Reservoirs Based on Fractal Fracture Networks and the EDFM. Processes. 2026; 14(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Hongsha, Man Chen, Shuang Li, Jianying Yang, Siliang He, and Ruihan Zhang. 2026. "Production Dynamics of Hydraulic Fractured Horizontal Wells in Shale Gas Reservoirs Based on Fractal Fracture Networks and the EDFM" Processes 14, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010114

APA StyleXiao, H., Chen, M., Li, S., Yang, J., He, S., & Zhang, R. (2026). Production Dynamics of Hydraulic Fractured Horizontal Wells in Shale Gas Reservoirs Based on Fractal Fracture Networks and the EDFM. Processes, 14(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010114