Green Synthesis and Characterization of Different Metal Oxide Microparticles by Means of Probiotic Microorganisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strains

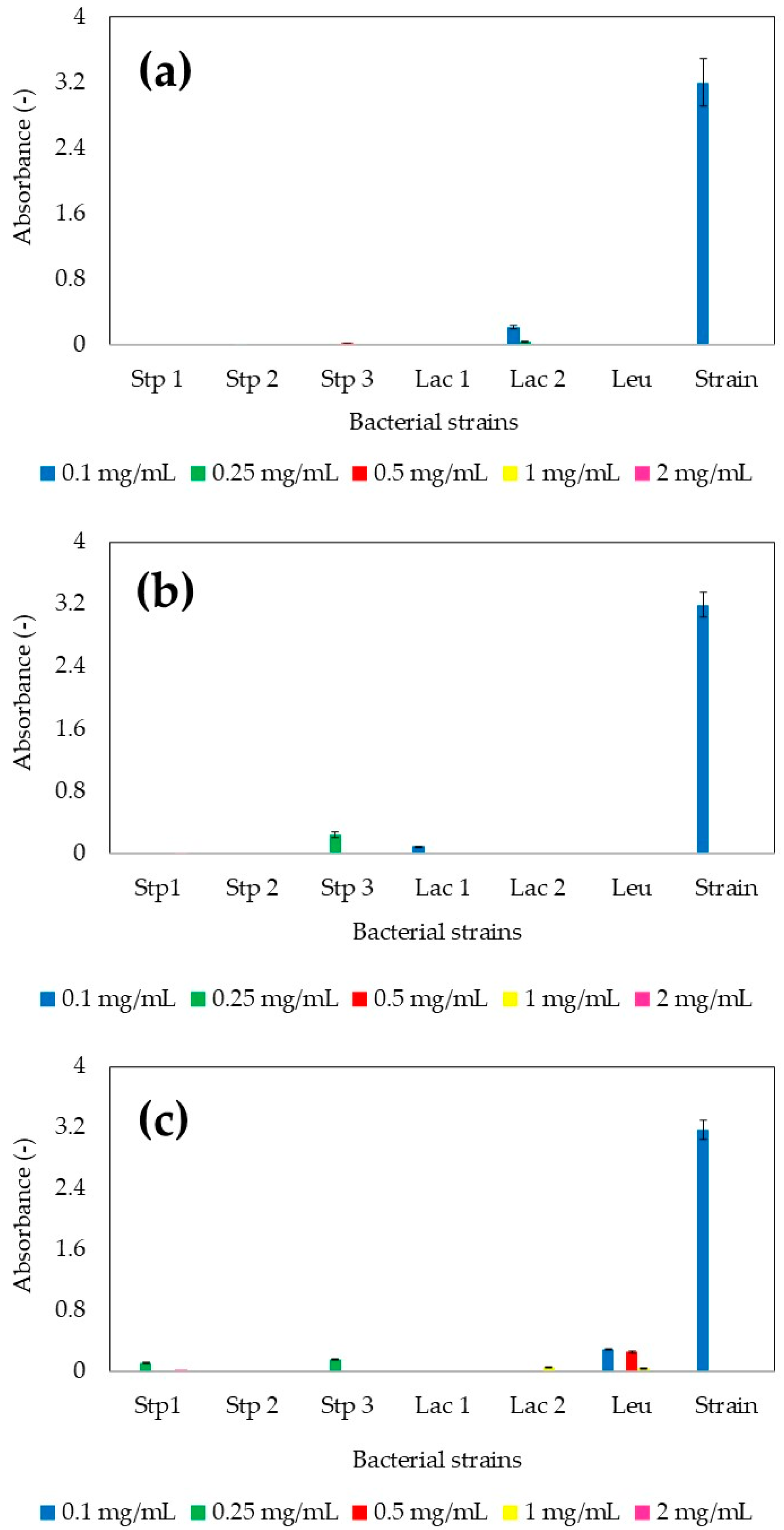

2.2. Standardization of the Precursor Salt Concentration Required for MP Production

2.3. Green Synthesis of MPs

2.4. Preliminary Characterization of MPs

2.4.1. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

2.4.2. Electrophoretic Mobility

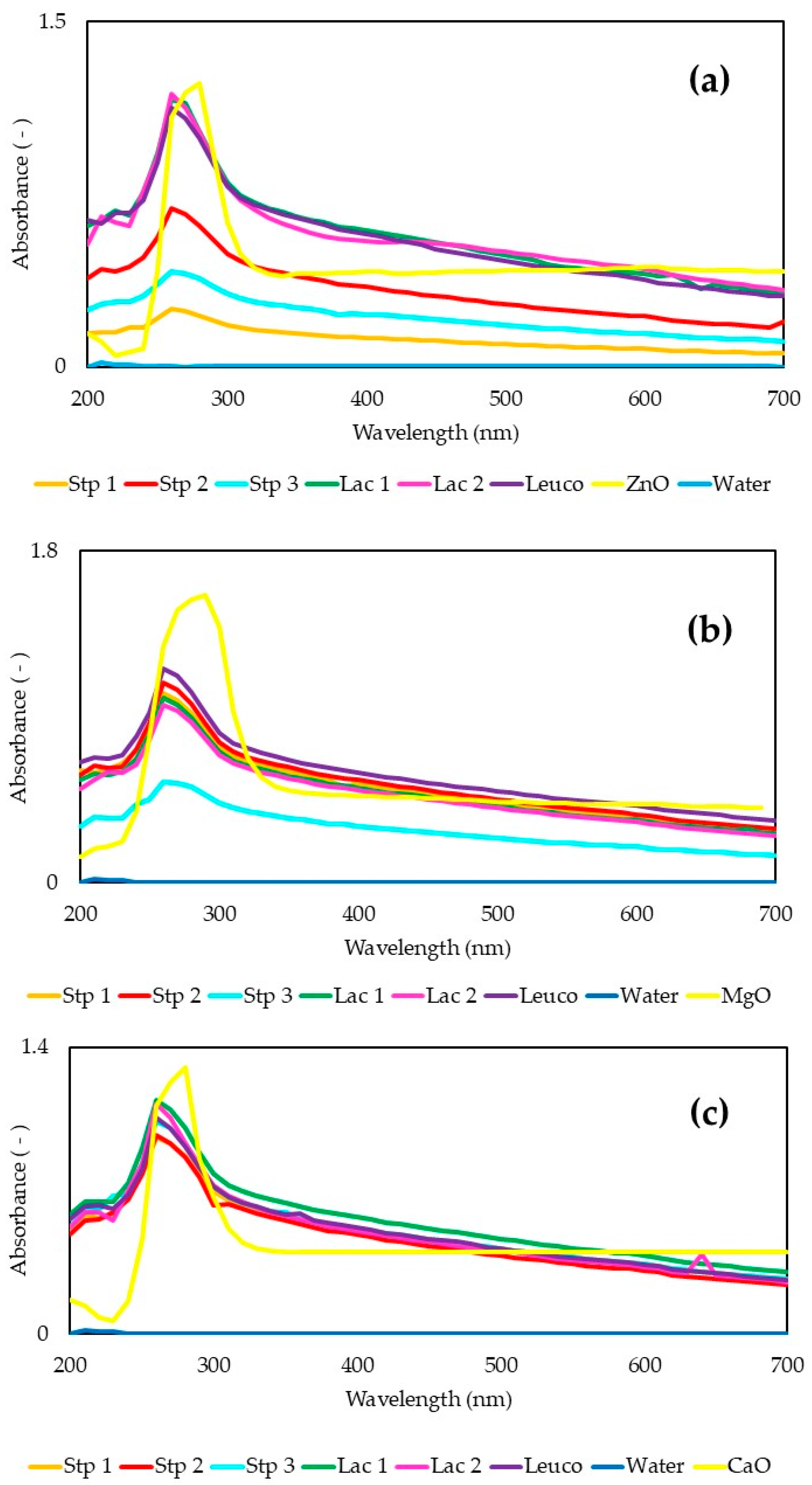

2.4.3. Spectrophotometry UV-Vis

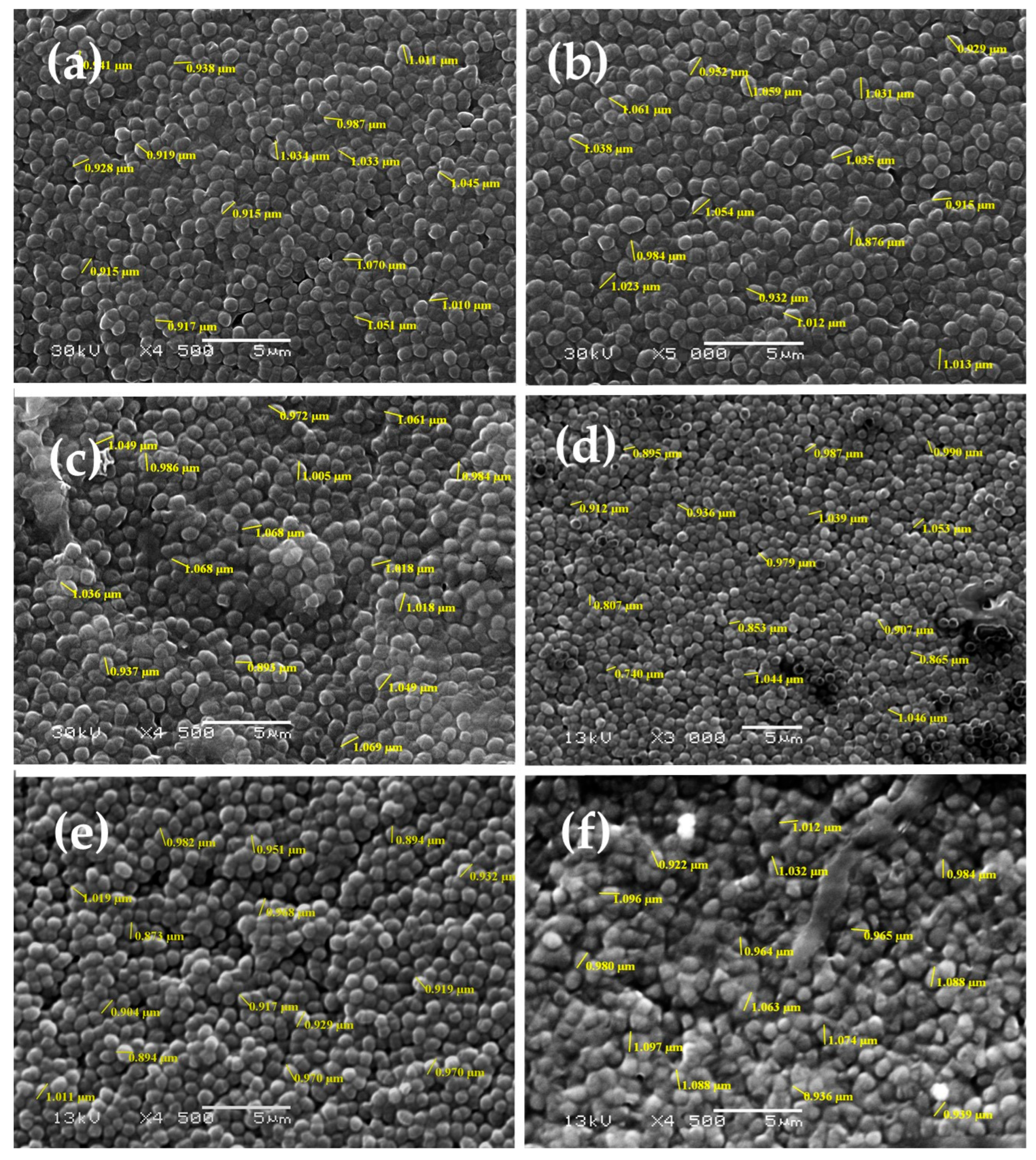

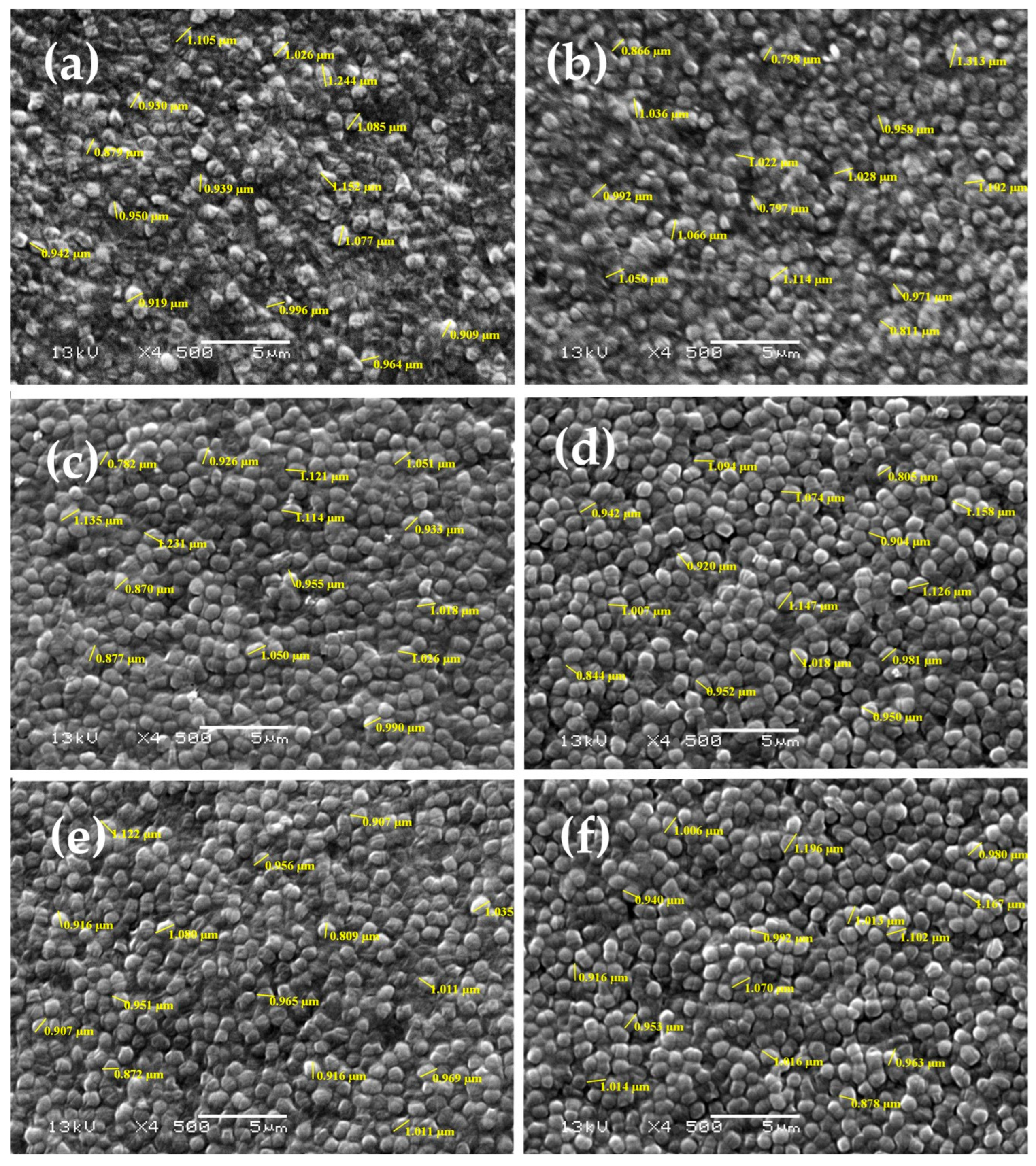

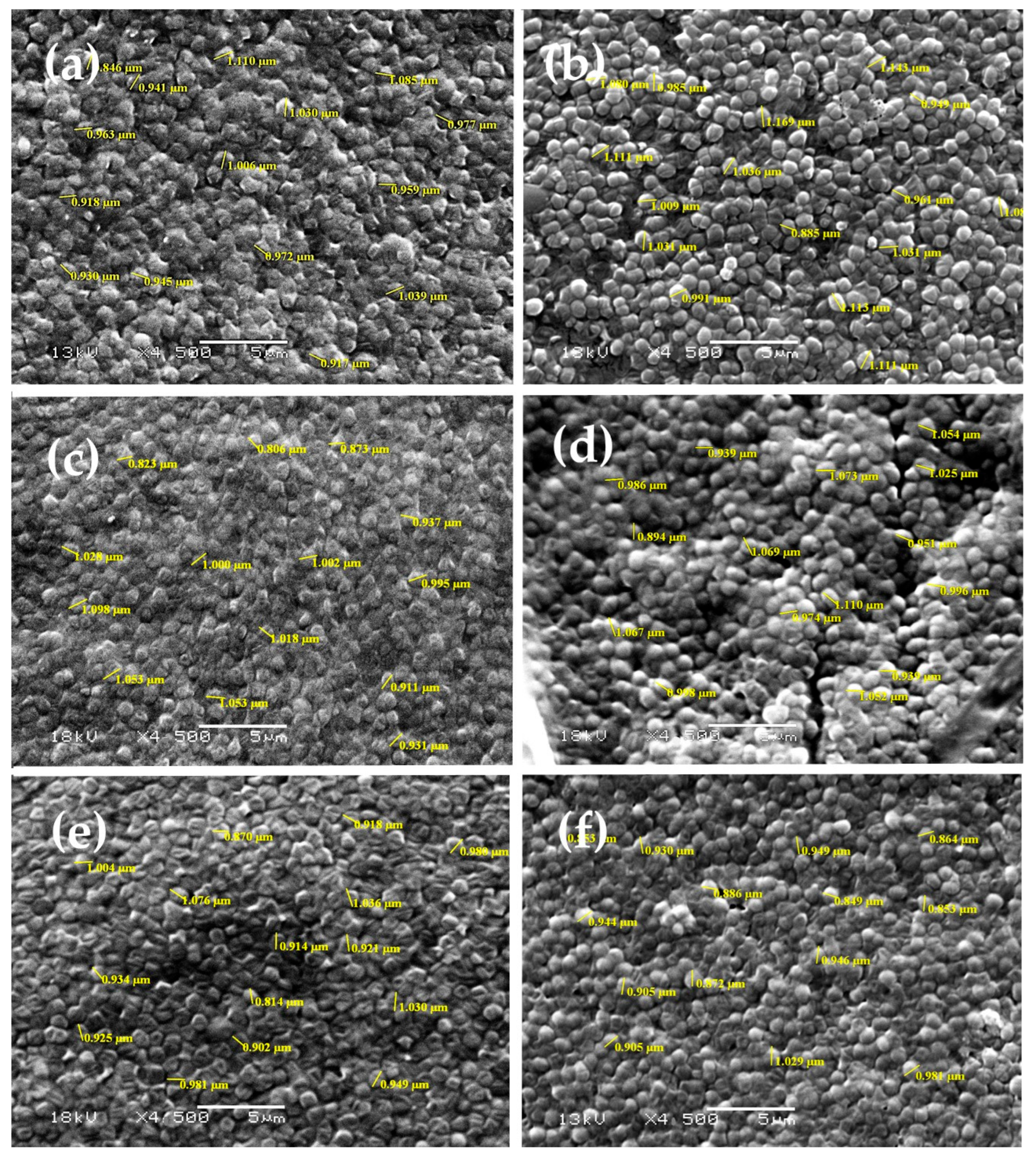

2.4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

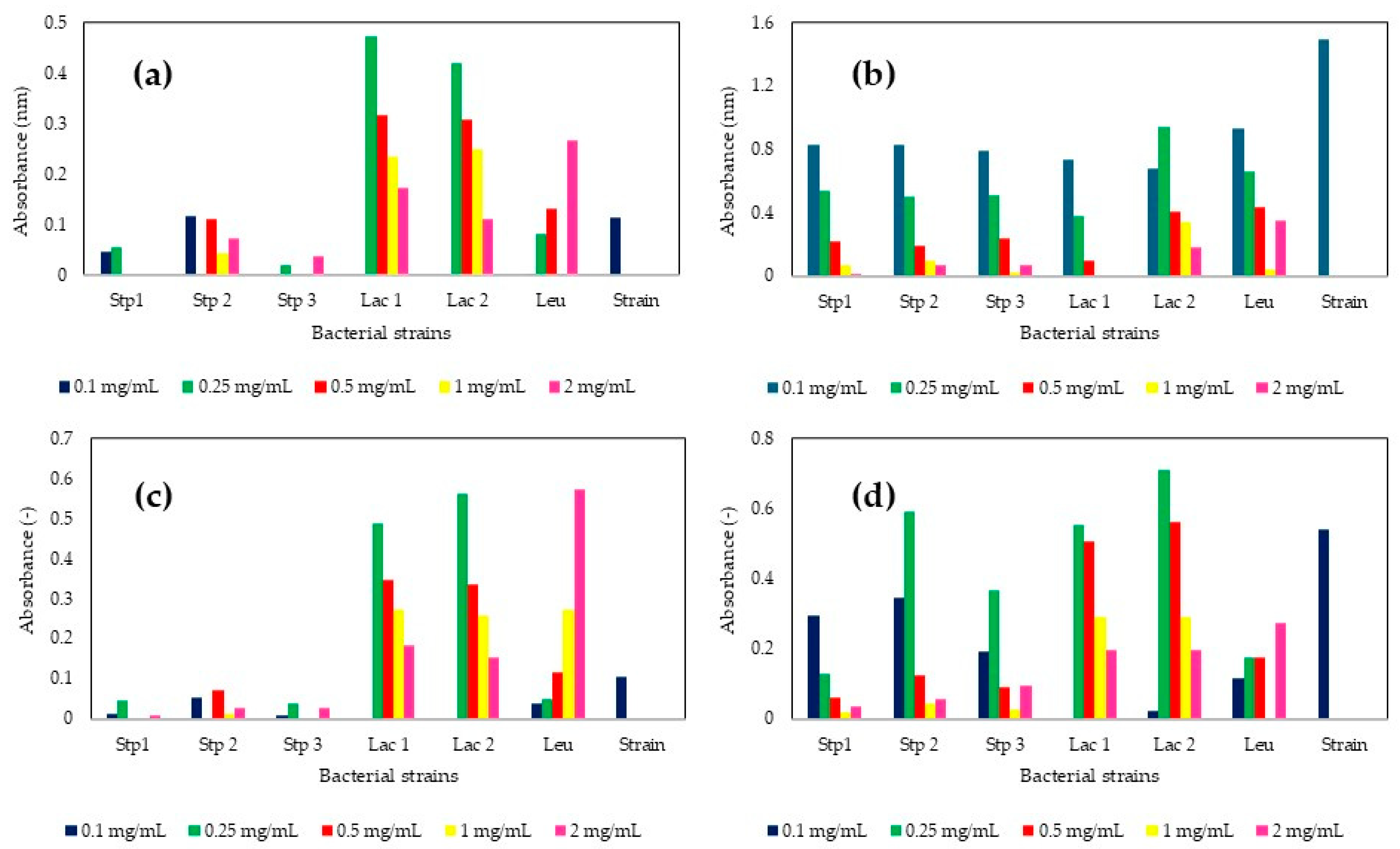

3.1. Standardization of the Precursor Salt Concentration Required for MP Production

3.2. MPs Preliminary Characterization

3.2.1. Spectrophotometry UV-Vis

3.2.2. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential

3.2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

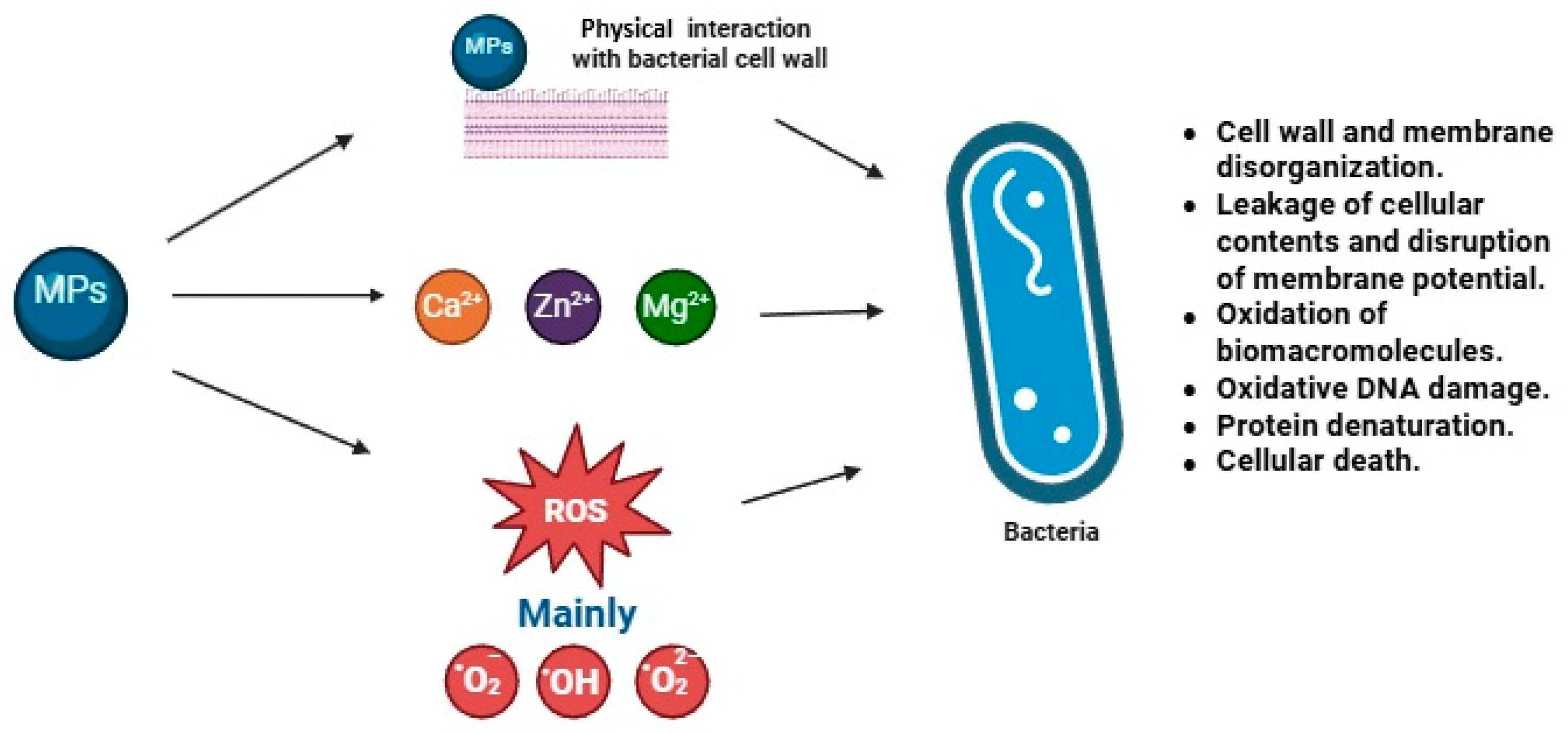

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity

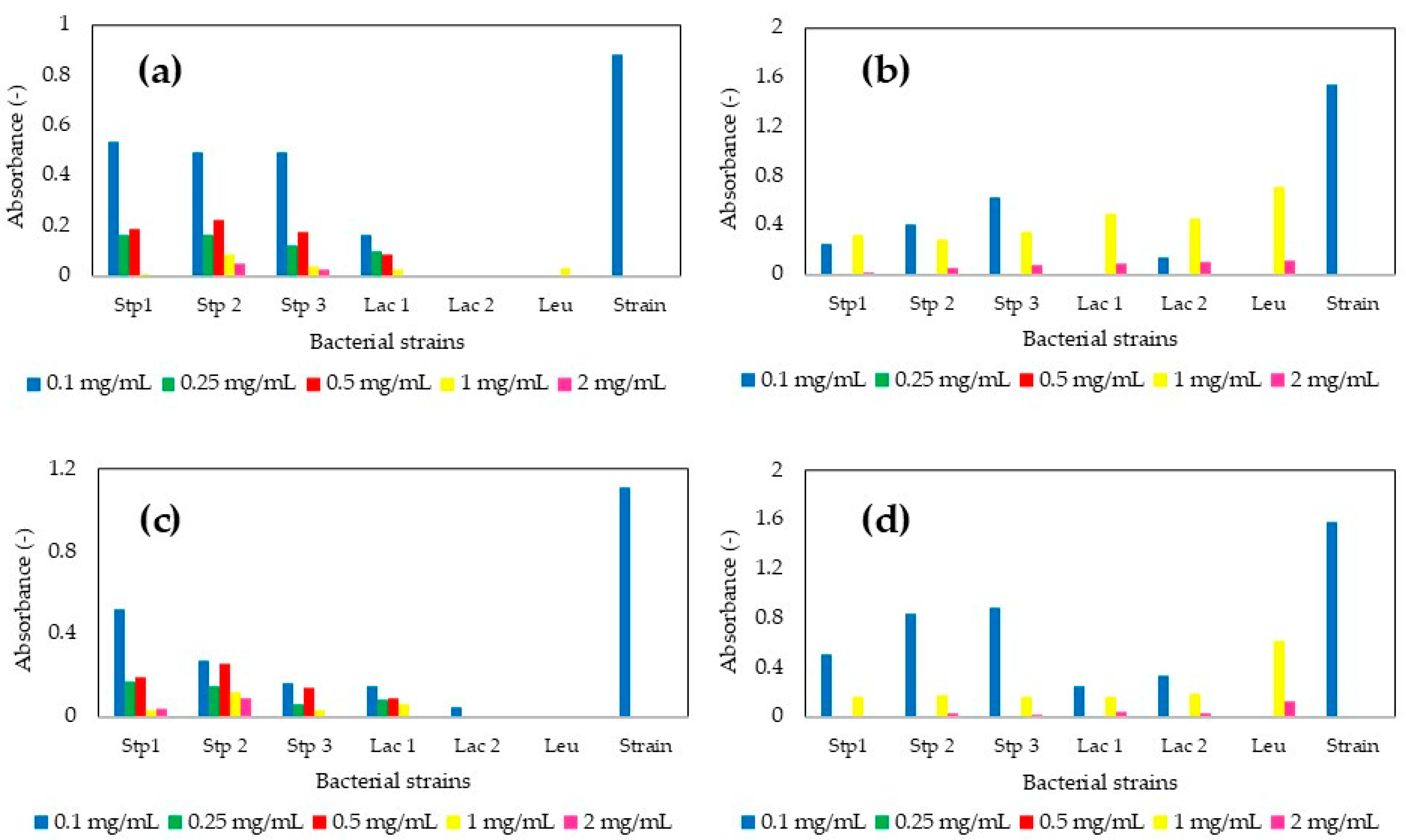

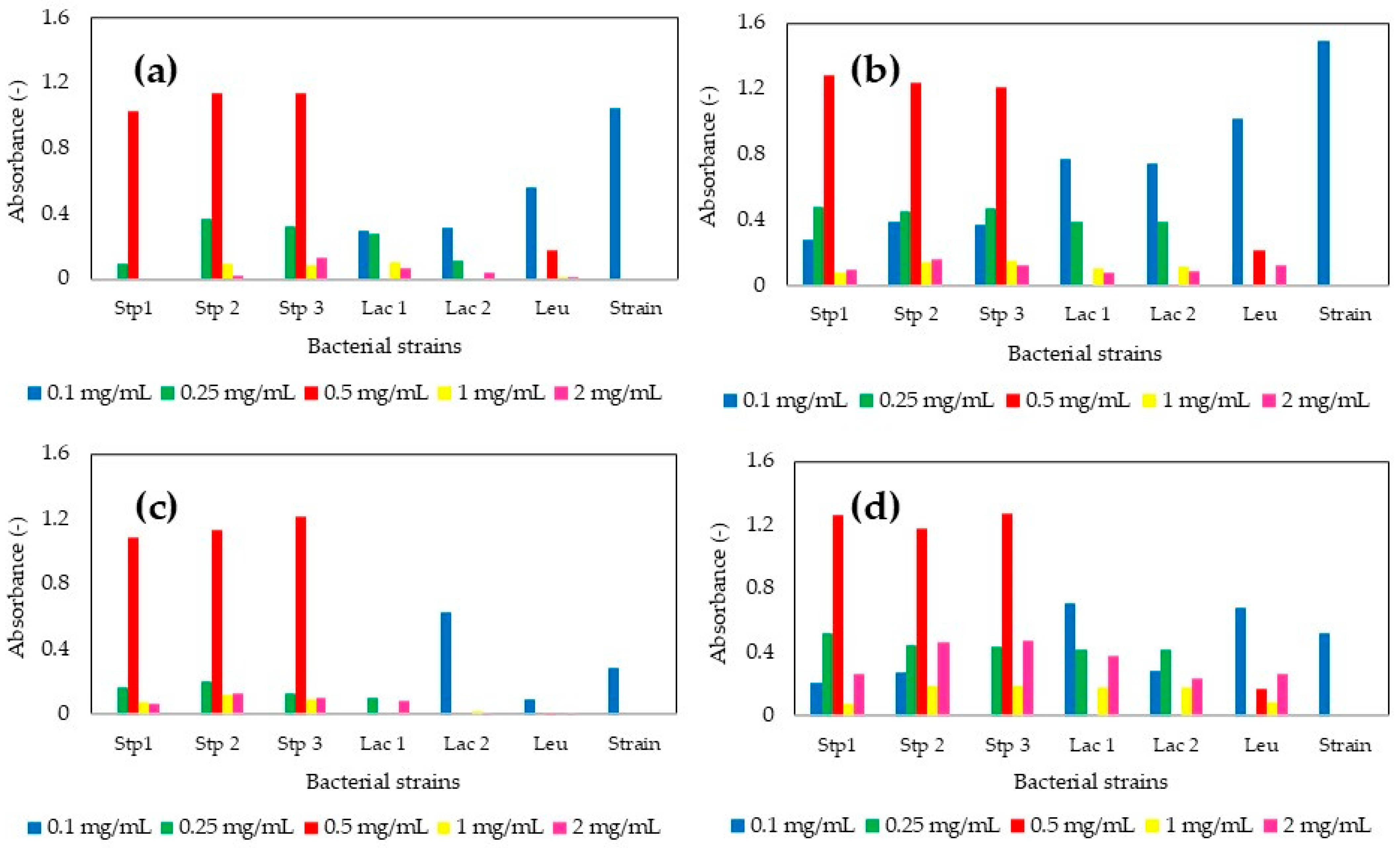

3.3.1. Evaluation Against Pathogens

3.3.2. Evaluation of the IC50 Value of the Metal Oxide MPs

3.3.3. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of the MPs Against a Phytopathogen Bacteria

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhujel, R.; Maharjan, R.; Kim, N.A.; Jeong, S.H. Practical quality attributes of polymeric microparticles with current understanding and future perspectives. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 64, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuillolay, C.; Haddioui, L.; Verelst, M.; Furiga, A.; Marchin, L.; Roques, C. Antimicrobial activity of metal oxide microspheres: An innovative process for homogeneous incorporation into materials. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.; Sasidharan, A.; Rani, V.V.D.; Menon, D.; Nair, S.; Manzoor, K.; Raina, S. Role of size scale of ZnO nanoparticles and microparticles on toxicity toward bacteria and osteoblast cancer cells. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009, 20, S235–S241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Tang, S.T.; Yun, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, R. Modular and integrated systems for nanoparticle and microparticles synthesis—A review. Biosensors 2020, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sahlany, S.T.G.; Niamah, A.K.; Verma, D.K.; Prabhakar, P.; Patel, A.R.; Thakur, M.; Singh, S. Applications of Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles Using Microorganisms in Food and Dairy Products: Review. Processes 2025, 13, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayyad, G.S.; Elfadil, D.; Mosleh, M.A.; Hasanien, Y.A.; Mostafa, A.; Abdelkader, R.S.; Refaey, N.; Elkafoury, E.M.; Eshaq, G.; Abdelrahman, E.A.; et al. Eco-Friendly Strategies for Biological Synthesis of Green Nanoparticles with Promising Applications. Bionanoscience 2024, 14, 3617–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirubakaran, D.; Wahid, J.B.A.; Karmegam, N.; Jeevika, R.; Sellapillai, L.; Rajkumar, M.; SenthilKumar, K.J. A Comprehensive Review on the Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Advancements in Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2026, 4, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.M.C.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Gonçalves, C.; Azinheiro, S.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Vicente, A.A.; Pastrana, L.M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Michelin, M. Green synthesis of lignin nano- and micro-particles: Physicochemical characterization, bioactive properties and cytotoxicity assesement. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 1798–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.; Viana, J.C. Optimisation of the green synthesis of Cu/Cu2O particles for maximum yield production and reduced oxidation for electronic applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 23, 114807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqra, R.K.; Begum, B.; Qazi, R.A.; Gul, H.; Khan, M.S.; Khan, S.; Bibi, N.; Han, C.; Rahman, N.U. Green synthesis of silver oxide microparticles using green tea leaves extract for an efficient removal of malachite green from water: Synergistic effect of persulfate. Catalysts 2023, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, N.M.; Raileanu, C.R.; Balta, A.A.; Ambrose, L.; Boev, M.; Marin, D.B.; Lisa, E.L. The Potential Impact of Probiotics on Human Health: An Update on Their Health-Promoting Properties. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, J.; Karthikeyan, E.; Rajeshkumar, S. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Eco-Friendly Advancements for Biomedical Marvels. Resour. Chem. Mater. 2024, 3, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhaymin, A.; Mohamed, H.E.A.; Hkiri, K.; Safdar, A.; Azizi, S.; Maaza, M. Green Synthesis of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles Using Hyphaene Thebaica Extract and Their Photocatalytic Activities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbonna, C.E.; Kavaz, D.; Olawade, D.B.; Adekunle, Y.A. Novel Green Synthesis of ZnO, CaO, and ZnO-CaO Hybrid Nanocomposites Using Extract of Foeniculum Vulgare (Fennel) Stalks: Characterization, Mechanical Stability, and Biological Activities. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 116, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Masood, A.; Ali, K.; Farid, N.; Bashir, A.; Dar, M.S. Green Synthesis of Silver, Starch, and Zinc Oxide Mediated Nanoparticles with Probiotics and Plant Extracts, Their Characterization and Anti-Bacterial Activity. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 196, 107012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Dou, X.; Song, X.; Xu, C. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Probiotics and Their Application. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 119, 83–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suba, S.; Vijayakumar, S.; Vidhya, E.; Punitha, V.N.; Nilavukkarasi, M. Microbial Mediated Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles Derived from Lactobacillus spp: Characterizations, Antimicrobial and Biocompatibility Efficiencies. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reza, R.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, H.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Alamilla-Beltrán, L.; Cruz-Narváez, Y.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L. Synthesis, Controlled Release, and Stability on Storage of Chitosan-Thyme Essential Oil Nanocapsules for Food Applications. Gels 2021, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayevska, N.; Przysiecka, Ł.; Iatsunskyi, I.; Nowaczyk, G.; Jarek, M.; Janiszewska, E.; Jurga, S. ZnO Size and Shape Effect on Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity Profile. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Ding, W. Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles: Effective Agricultural Antibacterial Agent against Ralstonia solanacearum. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, H.S.; El-Sayed, S.M.; Youssef, A.M. Novel Approach for Biosynthesizing of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Lactobacillus gasseri and Their Influence on Microbiological, Chemical, Sensory Properties of Integrated Yogurt. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Jangir, L.K.; Rathore, K.S.; Kumar, M.; Awasthi, K. Morphology-dependent structural and optical properties of ZnO nanostructures. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaralikhan, L.; Jaffar, M.J.M. Green Synthesis of MgO Nanoparticles and It Antibacterial Activity. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2018, 42, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankic, S.; Muller, M.; Diwald, O.; Sterrer, M.; Knözinger, E.; Bernardi, J. Size-Dependent Optical Properties of MgO Nanocubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4917–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, D.C.; Fernández, I.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E. MgO nanostructures: Synthesis, characterization and tentative mechanisms of nanoparticles formation. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2020, 23, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, V.; Bhagare, A.; Wahab, S.; Lokhande, D.; Vaidya, C.; Dhayagude, A.; Khalid, M.; Aher, J.; Mezni, A.; Dutta, M. Green Synthesized Calcium Oxide Nanoparticles (CaO NPs) Using Leaves Aqueous Extract of Moringa oleifera and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Activities. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 9047507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.R.; Ejaz, S.; Baron, J.C.; Ikram, M.; Ali, S. CaO nanoparticles as a potential drug delivery agent for biomedical applications. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2015, 10, 799–809. [Google Scholar]

- Król, A.; Railean-Plugaru, V.; Pomastowski, P.; Złoch, M.; Buszewski, B. Mechanism Study of Intracellular Zinc Oxide Nanocomposites Formation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 553, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, M.R. Impact of Particle Size and Polydispersity Index on the Clinical Applications of Lipidic Nanocarrier Systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, E.; Mohanasrinivasan, V. Biosynthesis and Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles Using Lactobacillus plantarum VITES07. Mater. Lett. 2013, 112, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Sarmiento, C.; Téllez-Medina, D.I.; Viveros-Contreras, R.; Cornejo-Mazón, M.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y.; García-Armenta, E.; Alamilla-Beltrán, L.; García, H.S.; Gutiérrez-López, G.F. Zeta Potential of Food Matrices. Food Eng. Rev. 2018, 10, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, T.S.S.K.; Singh, S.; Narasimhappa, P.; Varshney, R.; Singh, J.; Khan, N.A.; Zahmatkesh, S.; Ramamurthy, P.C.; Shehata, N.; Kiran, G.N.; et al. Green and Sustainable Synthesis of CaO Nanoparticles: Its Solicitation as a Sensor Material and Electrochemical Detection of Urea. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Z.S.; Baro, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Abolhasani, M. Flow Synthesis of Single and Mixed Metal Oxides. Chem. Methods 2022, 2, e202200007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizaj, S.M.; Lotfipour, F.; Barzegar-Jalali, M.; Zarrintan, M.H.; Adibkia, K. Antimicrobial Activity of the Metals and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 44, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Ingudam, S.; Reed, S.; Gehring, A.; Strobaugh, T.P.; Irwin, P. Study on the Mechanism of Antibacterial Action of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles against Foodborne Pathogens. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.U.; Hussain, T.; Abdullah; Khan, M.A.; Almostafa, M.M.; Younis, N.S.; Yahya, G. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Ficus Carica-Mediated Calcium Oxide (CaONPs) Phyto-Nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Masry, R.M.; Talat, D.; Hassoubah, S.A.; Zabermawi, N.M.; Eleiwa, N.Z.; Sherif, R.M.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Abdel-Sattar, R.M.; Gamal, M.; Ibrahim, M.S.; et al. Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activity of ZnO Nanoparticles against Enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus. Life 2022, 12, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Lloyd, M.D. Dose–Response Curves and the Determination of IC50 and EC50 Values. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 17931–17934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Olmos, A.R.; Vega Jiménez, A.L.; Paz Díaz, B. Mecanosíntesis y Efecto Antimicrobiano de Óxidos Metálicos Nanoestructurados. Mundo Nano Rev. Interdiscip. Nanociencias Y Nanotecnología 2018, 11, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, O. Influence of particle size on the antibacterial activity of zinc oxide. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 3, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalova, A.N.; Dushina, A.O. Metal/metal oxide nanoparticles with antibacterial activity and their potential to disrupt bacterial biofilms: Recent advances with emphasis on the underlying mechanisms. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 345, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Dai, R.; Chang, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, B. Antibacterial mechanism of biogenic calcium oxide and antibacterial activity of calcium oxide/polypropylene composites. Colloids Surf. A 2022, 650, 129446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Agudo, V.; Fernández-Calderón, M.C.; Pacha-Olivenza, M.A.; Pérez-Giraldo, C.; Gallardo-Moreno, A.M.; González-Martín, M.L. The role of magnesium in biomaterials related infections. Colloids Surf. B 2020, 191, 110996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yan, D.; Yin, G.; Liao, X.; Kang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huang, D.; Hao, B. Toxicological effect of ZnO nanoparticles based on bacteria. Langmuir 2008, 24, 4140–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.E.; Jin, H.E. Antimicrobial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nano/Microparticles and Their Combinations against Pathogenic Microorganisms for Biomedical Applications: From Physicochemical Characteristics to Pharmacological Aspects. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.A.; Tang, Y.; Naz, I.; Alam, S.S.; Wang, W.; Ahmad, M.; Najeeb, S.; Rao, C.; Li, Y.; Xie, B.; et al. Management of Ralstonia solanacearum in Tomato Using ZnO Nanoparticles Synthesized Through Matricaria chamomilla. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3224–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | PS (nm) ZnO-MPs | PDI (-) ZnO-MPs | PS (nm) MgO-MPs | PDI (-) MgO-MPs | PS (nm) CaO-MPs | PDI (-) CaO-MPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophilus ATCC 19987 | 1464 ± 119.4 | 0.242 ± 0.095 | 1633 ± 136.9 | 0.188 ± 0.109 | 1801 ± 101.0 | 0.282 ± 0.047 |

| S. thermophilus ATCC 19258 | 937.4 ± 129.6 | 0.287 ± 0.104 | 1600 ± 196.2 | 0.199 ± 0.032 | 1619 ± 362.5 | 0.566 ± 0.296 |

| S. thermophilus ATCC BAA 250 | 1433.6 ± 46.93 | 0.170 ± 0.062 | 1636 ± 241 | 0.158 ± 0.065 | 1592 ± 115.2 | 0.540 ± 0.239 |

| L. delbrueckii ATCC 11842 | 1491.6 ± 164.6 | 0.152 ± 0.102 | 1435 ± 169.2 | 0.238 ± 0.062 | 1569 ± 59.01 | 0.362 ± 0.035 |

| L. delbrueckii ATCC BAA 365 | 1477 ± 109.7 | 0.185 ± 0.037 | 1471 ± 214.8 | 0.367 ± 0.150 | 1634 ± 147.6 | 0.390 ± 0.295 |

| L. mesenteroides NRRL_B512F | 1394 ± 77.32 | 0.206 ± 0.029 | 1419 ± 193.8 | 0.184 ± 0.061 | 1525 ± 107.3 | 0.355 ± 0.064 |

| ζ (mV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | ZnO-MPs | MgO-MPs | CaO-MPs |

| S. thermophilus ATCC 19987 (Stp 1) | 17.0 ± 0.72 a | 19.44 ± 0.55 ab | 21.10 ± 0.40 b |

| S. thermophilus ATCC 19258 (Stp 2) | 17.87 ± 0.55 a | 19.90 ± 0.30 ab | 17.83 ± 0.93 b |

| S. thermophilus ATCC BAA 250 (Stp 3) | 20.27 ± 2.42 a | 17.50 ± 0.63 ab | 20.87 ± 1.31 b |

| L. delbrueckii ATCC 11842 (Lac 1) | 22.07 ± 3.76 a | 16.46 ± 1.31 ab | 20.93 ± 1.01 b |

| L. delbrueckii ATCC BAA 365 (Lac 2) | 17.53 ± 1.80 a | 20.90 ± 0.44 ab | 20.33 ± 1.67 b |

| L. mesenteroides NRRL_B512 F (Leu) | 16.34 ± 4.75 a | 22.30 ± 0.70 ab | 22.13 ± 0.59 b |

| Strain | PS ± SD (nm) ZnO-MPs | CV (%) ZnO-MPs | PS ± SD (nm) MgO-MPs | CV (%) MgO-MPs | PS ± SD (nm) CaO-MPs | CV (%) CaO-MPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. thermophilus ATCC 19987 | 936.87 ± 94.68 | 10.11 | 994.8 ± 107.98 | 10.85 | 1005.8 ± 63.33 | 6.30 |

| S. thermophilus ATCC 19258 | 942.2 ± 43.79 | 4.65 | 958.29 ± 82.77 | 8.64 | 950.27 ± 68.5 | 7.21 |

| S. thermophilus ATCC BAA 250 | 1016 ± 64.35 | 6.33 | 1013.73 ± 88.24 | 8.70 | 914.14 ± 51.97 | 5.69 |

| L. delbrueckii ATCC 11842 | 1010.43 ± 51.48 | 5.09 | 1004.36 ± 122.91 | 12.24 | 969 ± 91.67 | 9.46 |

| L. delbrueckii ATCC BAA 365 | 980.93 ± 56.05 | 5.71 | 1006.5 ± 107.96 | 10.73 | 980.07 ± 69.3 | 7.07 |

| L. mesenteroides NRRL_B512F | 992.93 ± 61.11 | 6.15 | 995.33 ± 138.73 | 13.94 | 1038.27 ± 78.32 | 7.54 |

| Microorganism | MP | Synthesized by | C (Abs600) | D (Abs600) | IC50 (mg/mL) | b | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella | ZnO | Lac 1 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.278 | 0.737 | 0.959 |

| Salmonella | ZnO | Lac 2 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 0.222 | 0.707 | 0.946 |

| S. aureus | ZnO | Stp 1 | 0.00 | 1.50 | 0.119 | 1.220 | 0.973 |

| S. aureus | ZnO | Str 2 | 0.05 | 1.50 | 0.118 | 1.162 | 0.986 |

| E. coli 35218 | ZnO | Lac 1 | 0.20 | 1.10 | 0.180 | 0.612 | 0.991 |

| E. coli 35218 | ZnO | Lac 2 | 0.17 | 1.10 | 0.253 | 0.895 | 0.962 |

| E. coli 8739 | ZnO | Lac 1 | 0.20 | 1.50 | 0.133 | 0.648 | 0.952 |

| Salmonella | MgO | Stp 2 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.112 | 1.091 | 0.867 |

| E. coli 35218 | MgO | Stp 1 | 0.05 | 1.10 | 0.089 | 1.522 | 0.925 |

| S. aureus | CaO | Lac 1 | 0.10 | 1.50 | 0.108 | 1.087 | 0.991 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cruz-Rodríguez, C.; González-Reza, R.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, H. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Different Metal Oxide Microparticles by Means of Probiotic Microorganisms. Processes 2026, 14, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010101

Cruz-Rodríguez C, González-Reza RM, Hernández-Sánchez H. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Different Metal Oxide Microparticles by Means of Probiotic Microorganisms. Processes. 2026; 14(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz-Rodríguez, Claudia, Ricardo Moisés González-Reza, and Humberto Hernández-Sánchez. 2026. "Green Synthesis and Characterization of Different Metal Oxide Microparticles by Means of Probiotic Microorganisms" Processes 14, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010101

APA StyleCruz-Rodríguez, C., González-Reza, R. M., & Hernández-Sánchez, H. (2026). Green Synthesis and Characterization of Different Metal Oxide Microparticles by Means of Probiotic Microorganisms. Processes, 14(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010101