A Comprehensive Review of Research on Pulsating Beds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Introducing Pulsation into a Fluidized Bed

3. Pulsation Parameters

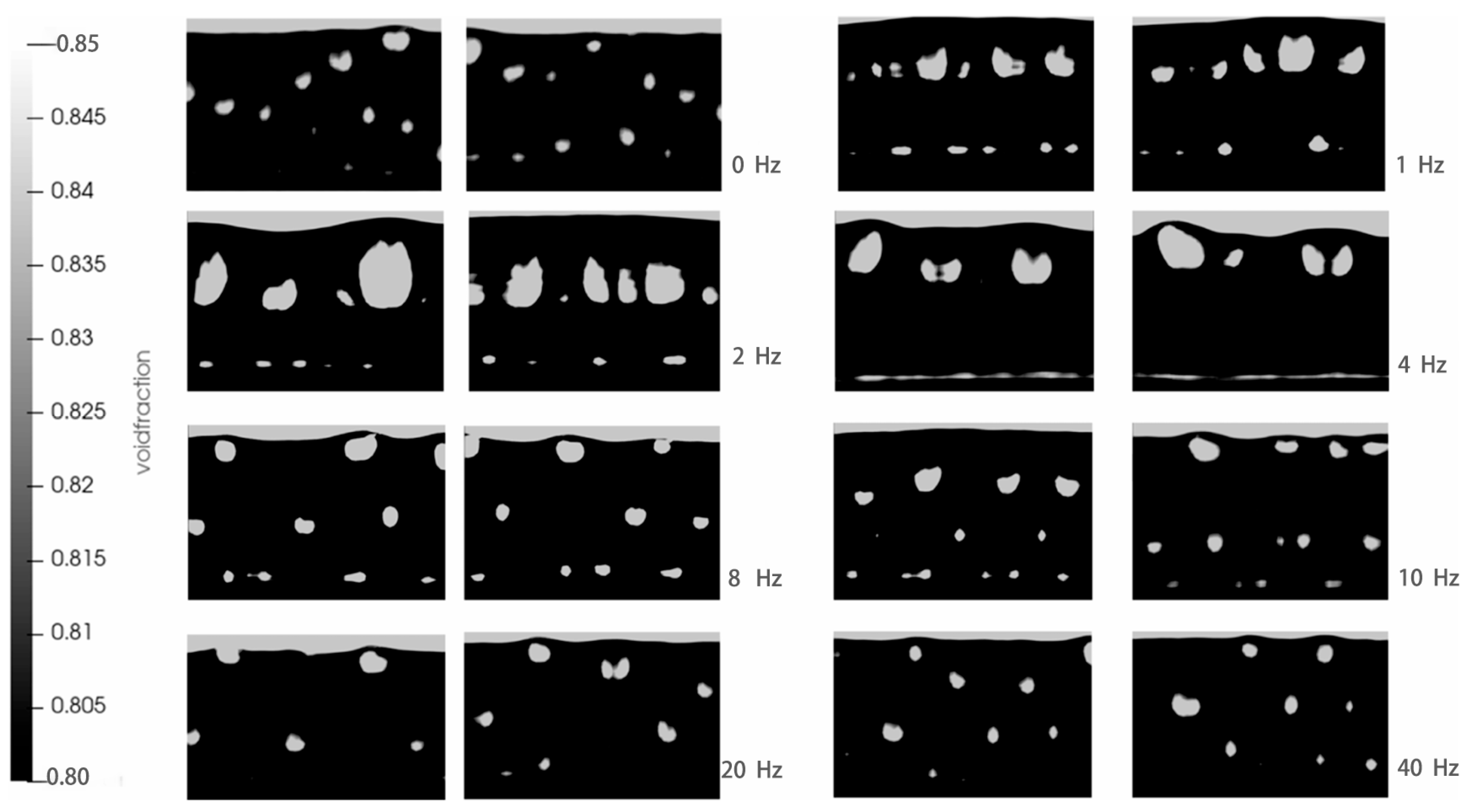

3.1. Pulsation Frequency

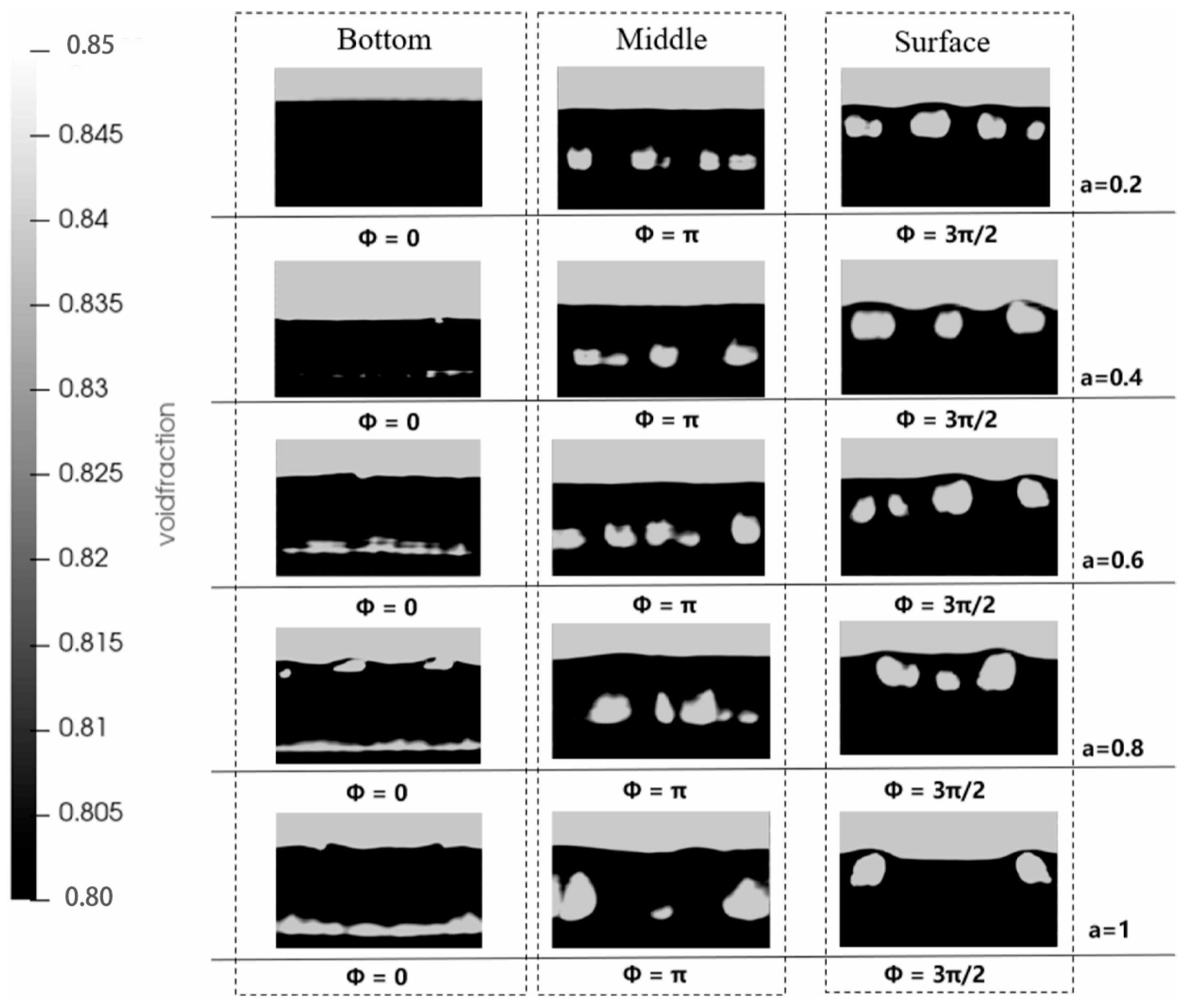

3.2. Pulsation Amplitude and Air Distribution Ratio

- Suitable base airflow: It is essential to precisely control the base airflow within the homogeneous fluidization region, approaching the minimum fluidization velocity, in order to create initial conditions conducive to the generation of regular bubbles.

- Optimized Pulsation Amplitude: Building upon this foundation, an adequately large yet non-excessive pulsation amplitude is applied to effectively drive the periodic formation of channel-like structures, thereby “seeding” a regular sequence of bubbles. This provides crucial theoretical guidance for the precise regulation of airflow combinations in practical applications, aimed at achieving specific fluidization patterns (such as orderly bubbling to enhance reaction selectivity).

3.3. Waveform

3.4. Base Flow Gas Velocity

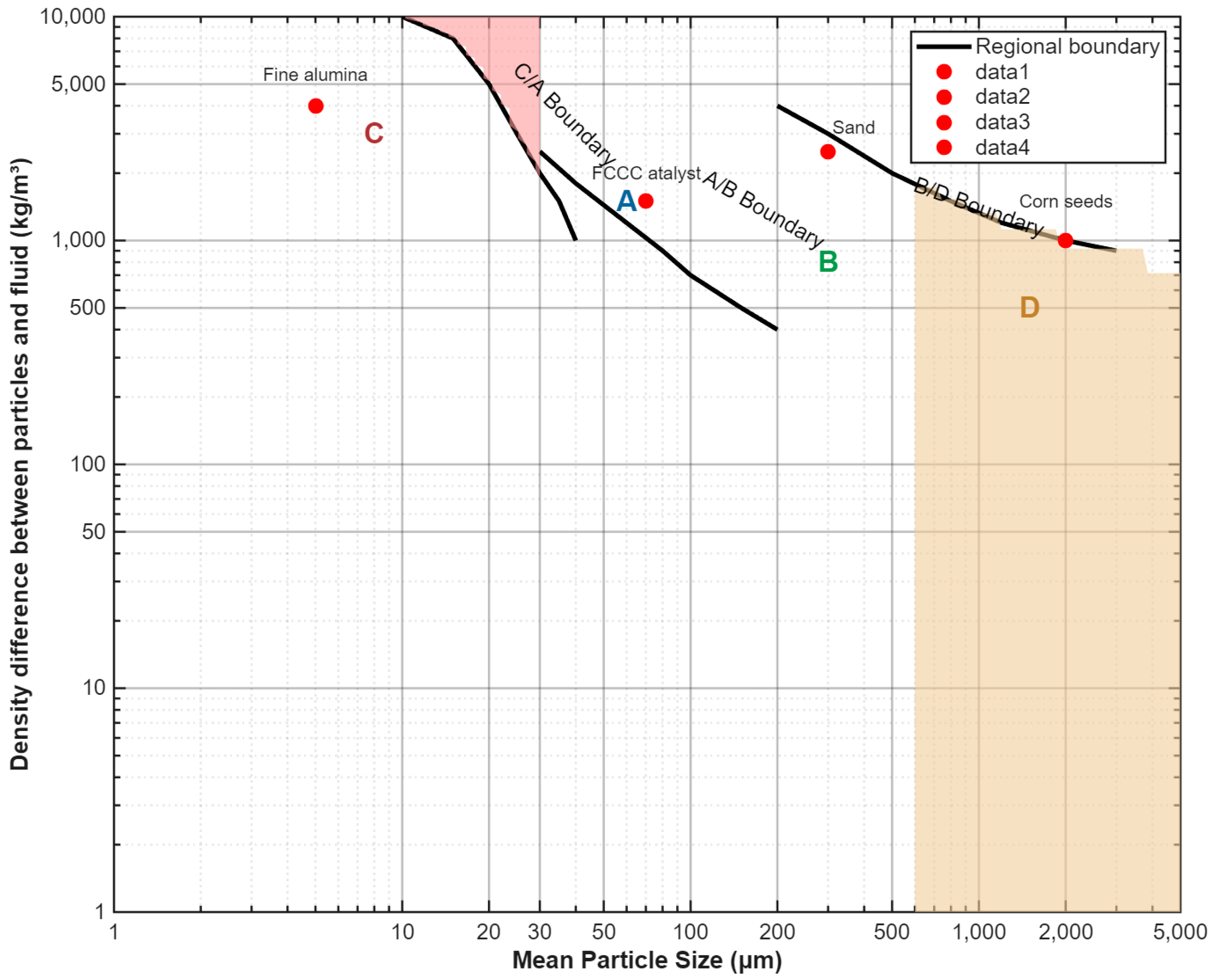

3.5. Particle Size

3.6. Flow Patterns of Pulsating Fluidized Bed

- In the SD mode, residual gases are expelled solely from the top of the bed. This phenomenon results in a dominant upward drag force that delays the collapse of the bed and facilitates the accumulation of fine particles in the upper region, thereby exacerbating size segregation among agglomerates.

- In the DD mode, gas can be discharged simultaneously from both the top and bottom, which reduces airflow resistance and accelerates the collapse rate of the bed. However, due to the presence of initial flow peaks, a pronounced phenomenon of agglomerate layering still occurs, with agglomerate sizes in the lower region being significantly larger than those in the middle and upper regions.

- The MDD pattern utilizes a four-way valve to redirect the inlet gas flow to the atmosphere during collapse, thereby eliminating initial flow spikes and significantly suppressing the size-based separation of agglomerates. Under this pattern, bed collapse occurs more rapidly and smoothly. Frequency domain analysis reveals a substantial reduction in pressure fluctuation amplitude, indicating an enhancement in bed stability.

4. Research Progress

4.1. Hydrodynamics

4.1.1. Granule

4.1.2. Pressure Drop and the Minimum Fluidization Velocity

4.1.3. Characteristics of Bubbles

4.2. Bed Layer Expansion and Falling Bed Phenomenon

- To shorten the settlement time of the bed layer and prevent complete collapse;

- Enhanced particle movement and bed elasticity, while maintaining partial expansion;

- Third item. Significantly reduce the minimum fluidization velocity and enhance the quality of fluidization at low gas velocities;

- It is particularly suited for nanoparticles that exhibit high cohesion and a tendency to aggregate, such as hydrophilic ABF-type particles.

4.3. Mixing and Segregation

4.4. Heat Transfer and Mass Transfer

4.5. Comparison of Main Numerical Models for Pulsating Fluidized Beds

5. Engineering Challenges and Scale-Up Considerations

5.1. Energy Consumption and Pulsation Generation

5.2. Actuator and Mechanical System Reliability

5.3. Distributor Design for Uniform Pulsation

5.4. Particle Attrition and Erosion

5.5. Scale-Up Methodology and Modeling

6. Conclusions and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamed, K.B.; Hassan, B.T. Experimental study on hydrodynamic characteristics of gas–solid pulsed fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2013, 237, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, I.; Kate, P.; Rachel, S. A review of pulsed flow fluidisation; the effects of intermittent gas flow on fluidised gas–solid bed behaviour. Powder Technol. 2016, 292, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maysam, S.; Hassan, B.T.; John, R.G. A review on pulsed flow in gas-solid fluidized beds and spouted beds: Recent work and future outlook. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanjiao, L.; Yuemin, Z.; Yutong, L.; Bin, Y.; Han, G.; Liang, D. Research on fluidization characteristies of different particles based on pulsating gas flow. J. Shandong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 39, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fenglong, Z. Study on the Synergistic Upgrading of Fine Lignite by Drying and Separating in Pulsed Gas-Solid Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zengqiang, C.; Lei, Y.; Guangxin, Z.; Tong, X.; Fenglong, Z.; Chenlong, D.; Liang, D.; Yuemin, Z. Synergy of drying and separation of fine lignite in pulsed gas-solid fluidized bed. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2023, 52, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Liu, D. Dynamics of collapsing fluidized beds and its application in the simulation of pulsed fluidized beds. Powder Technol. 1998, 99, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, A.; Rahman, F.; Wang, S.; Rhodes, M. Enhanced fluidization of nanoparticles with gas phase pulsation assistance. Powder Technol. 2015, 284, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Asif, M. Fluidization of nano-powders: Effect of flow pulsation. Powder Technol. 2012, 225, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barletta, D.; Russo, P.; Poletto, M. Dynamic response of a vibrated fluidized bed of fine and cohesive powders. Powder Technol. 2013, 237, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Davidson, J.; Tuponogov, V. The velocity of sound in fluidised beds. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1990, 45, 3233–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanjiao, L.; Kun, H.; Chenyang, Z.; Yuemin, Z.; Chenlong, D.; Liang, D. Vibration energy transfer in a forced oscillation fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D. Study on the Mechanism of Fluidization and Separation of the Pulsed Dense-Phase Fluidized Bed. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhou, E.; Cai, L.; Zhang, B.; Duan, C. Effect of active pulsing air flow on gas-vibro fluidized bed for fine coal separation. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ohara, H.; Tsutsumi, A. Pulsation-assisted fluidized bed for the fluidization of easily agglomerated particles with wide size distributions. Powder Technol. 2017, 316, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Rhodes, M.J. Pulsed fluidization—A DEM study of a fascinating phenomenon. Powder Technol. 2005, 159, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhikai, M. Flow Characterization of Pulsating Fluidized Bed Nanoparticle Agglomerates Based on the DQMOM Approach. Master’s Thesis, Harbin University of Science and Technology, Harbin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiqiao, W.; Martín, L.d.; Coppens, M.-O. Pattern formation in pulsed gas-solid fluidized beds—The role of granular solid mechanics. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 329, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dening, J.; Cathary, O.; Jianghong, P.; Xiaotao, B.; Lim, C.J.; Sokhansanj, S.; Yuping, L.; Ruixu, W.; Tsutsumi, A. Fluidization and drying of biomass particles in a vibrating fluidized bed with pulsed gas flow. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 138, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, A.; van Ommen, J.R.; Nijenhuis, J.; Wang, X.S.; Coppens, M.-O.; Rhodes, M.J. Improved drying in a pulsation-assisted fluidized bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.W.; Seung, J.H.; Wook, B.J.; Young, K.J.; Hyun, L.D. Segregation phenomena of binary solids in a pulsed fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2022, 410, 117881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanian, J.; Jafari, R.; Chaouki, J. Fluidization of ultrafine powders. Int. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2012, 4, 16–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ruud, V.O.J.; Manuel, V.J.; Robert, P. Fluidization of nanopowders: A review. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14, 737. [Google Scholar]

- Raganati, F.; Chirone, R.; Ammendola, P. Gas–solid fluidization of cohesive powders. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 133, 347–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Arsad, A.; Asif, M. Effect of modified inlet flow strategy on the segregation phenomenon in pulsed fluidized bed of ultrafine particles: A collapse bed study. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2021, 159, 108243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherntongchai, P.; Brandani, S. A model for the interpretation of the bed collapse experiment. Powder Technol. 2005, 151, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandani, S.; Zhang, K. A new model for the prediction of the behaviour of fluidized beds. Powder Technol. 2006, 163, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherntongchai, P.; Brandani, S. Prediction ability of a new minimum bubbling criterion. Adv. Powder Technol. 2013, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Ali, S.S. Bed collapse dynamics of fluidized beds of nano-powder. Adv. Powder Technol. 2013, 24, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Al-Ghurabi, E.H.; Ajbar, A.; Mohammed, Y.A.; Boumaza, M.; Asif, M. Effect of Frequency on Pulsed Fluidized Beds of Ultrafine Powders. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 4592501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Al-Ghurabi, E.H.; Ajbar, A.; Kumar, N.S. Hydrodynamics of Pulsed Fluidized Bed of Ultrafine Powder: Fully Collapsing Fluidized Bed. Processes 2020, 8, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Boumaza, M.M.; Al-Ghurabi, E.H.; Shahabuddin, M. Improving the Fluidization Hydrodynamics of Cohesive Powder Using Pulsed Flow. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 46491–46500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maysam, S.; Hassan, B.T.; Sina, C.; Majid, D. Pulsating flow effect on the segregation of binary particles in a gas–solid fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2014, 264, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Simulation of Segregation Behaviors of Binary Mixture in a Fluidized Bed with Pulsed Flow. Energy Conserv. Technol. 2021, 39, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, D.; Haifeng, L.; Jie, T.; Haifeng, L. Characterization of powder flow properties from micron to nanoscale using FT4 powder rheometer and PT-X powder tester. Particuology 2023, 75, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, A.S.; Agus, A.; Roberts, K.L.; Mohammad, A. Effect of Inlet Flow Strategies on the Dynamics of Pulsed Fluidized Bed of Nanopowder. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, E.; Ao, O.A. Fluid flow through randomly packed columns and fluidized beds. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1949, 41, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Zhang, X.H.; Liang, Z.; Hui, D. Experiment of Resistance Characteristics for Magnesite PelletsPacked Bed Based on Ergun Equation. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2021, 42, 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Su, W. Euler-Euler Method Simulating Pulsed Fluidized Bed Behaviors. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Huang, Q.; Dong, L. Characterization of bubble behaviors in a dense phase pulsed gas–solid fluidized bed for dry coal processing. Particuology 2020, 53, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X. Study on Fluidization Characteristics of Air Heavy Medium Pulsed Fluidized Bed. Coal Sci. Technol. 2011, 39, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Zhanyong, L.; Jingsheng, Y.; Ling, L. Study of Bubble Characteristics in a Pulsed Fluidized Bed. J. Tianjin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 22, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, J.; Yong, Z.; Ji, X.; Chenlong, D.; Yuemin, Z.; Wei, G. Formation of Ordered Bubbles in Pulsed Fluidized Beds─A CGDPM Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 3797–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Expanslon and Mlxing for A Pulsofluidized Bed. J. Shandong Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1996, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Su, W.; Li, Z.; Ye, J. Numerical Simulation of Pulsed Fluidized Beds. Chem. Eng. Mach. 2009, 36, 256–258+271. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Y.; Pan, B.; Gao, X.Y.; Hu, Y.J. Particle Mixing and Segregation of Binary Mixtures in Fluidized Beds with Additional Pulsating Air Flow. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2015, 46, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, H.; Wei, D. Study on Mixing Characteristics of Gas-Solid Pulsed Fluidized Bed. Chem. Equip. Technol. 2007, 28, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C. The Mixing and Separation of Characteristics in Pulsed Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Q. Simulation of the Mixing Characteristics in Two-component Pulsed Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Lou, X.; Qian, D.; Li, L.; Xu, T. Numerical Simulation of Mixing Characteristies of GreenBean Particles in Pulsating Fluidized Bed. Light Ind. Mach. 2024, 42, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Bo, X. Research on heat transfer and drying characteristics between gas and solid in pulsed-fluidized bed. J. Shandong Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 19, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ohara, H. Heat Transfer and Fluidization Characteristics of Lignite in a Pulsation-Assisted Fluidized Bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 8995–9005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.E.M.; Chuan, L.E.W. Heat transfer from immersed tubes in a pulsating fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2018, 327, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G. The Study of Drying Characteristics in Pulsed Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Electric Power University, Jilin, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, W. Muti-Scale Analysis and CFD-DEM Numerical Simulation of Flow and Heart Transfer Characteristics in Pulsating Fluidized Bed. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Electric Power University, Jilin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, A.; Kazemi, S.; Hamidani, G.; Zarghami, R.; Mostoufi, N. CFD-DEM modeling of biomass pyrolysis in a DBD plasma fluidized bed. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 196, 152553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Y. CFD-DEM study of thermal behaviours of chip-like particles flow in a fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2024, 445, 120066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoda, S.; Mladenovic, M.; Paprika, M.; Eric, A.; Grubor, B.D. Three phase Eulerian-granular model applied on numerical simulation of non-conventional liquid fuels combustion in a bubbling fluidized bed. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongming, G. High-performance manufacturing. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 060201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guolong, Z.; Biao, Z.; Wenfeng, D.; Lianjia, X.; Zhiwen, N.; Jianhao, P.; Ning, H.; Jiuhua, X. Nontraditional energy-assisted mechanical machining of difficult-to-cut materials and components in aerospace community: A comparative analysis. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 022007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Cheung, C.F.; Shokrani, A.; Zhan, Z.; Wang, C. Atomic-level flat polishing of polycrystalline diamond by combining plasma modification and chemical mechanical polishing. CIRP Ann. 2025, 74, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparison Criteria | CFD-DEM | Eulerian-Granular | PBM-Coupled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy and Scale | Micro/meso: Fluid as a continuous phase (Euler), tracking the motion of each particle individually (Lagrangian). | Macro perspective: Both fluid and particulate phases are regarded as mutually permeable continuous media | Mesoscopic/Macroscopic: Within the framework of Euler or Euler-Lagrange, we introduce a statistical evolution of particle size distribution. |

| The Applicability of Pulsating Flow | The method is highly suitable for directly analyzing the transient response of a single particle under periodic external forces, as well as the processes of formation and disintegration of particle aggregates. | The method demonstrates high computational efficiency; however, its resolution is limited. It is capable of capturing the overall periodic expansion and collapse of the bed layers but struggles to directly elucidate the micro-dynamics of particle agglomeration. | Core value lies in describing the dynamic evolution of particle size distribution over time/space under pulsating conditions (e.g., fine powder coalescence leading to increased average particle size). |

| Key Model Assumptions and Differences | Collision Model: Specify the restitution coefficient and friction coefficient, which are crucial for energy dissipation.

|

|

|

| Refine costs | Extremely high | Low | Moderate |

| Primary Advantages |

|

|

|

| Min Limitations |

|

|

|

| Parameters | Bubble Dynamics | Mixing Quality | Segregation Tendency | Heat Transfer | Energy Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency ↑ | ↓ Then—/↑ | Bubble Size ↓ Quantity ↑ | ↑ Then ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Amplitude ↑ | ↓↓ | Bubble Size ↓↓ Quantity ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Baseline flow ↑ | — | Bubble Size ↑↑ Quantity ↓ | ↑ Then ↓ | ↑ | Gas-Solid ↑ | ↑↑ |

| Duty cycle ↑ | ↑ | Bubble Size ↑ Quantity ↓ | ↑ Then ↓ | ↑ | Heat Transfer: Floor to Wall ↓ | ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Yuan, D.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Hong, K. A Comprehensive Review of Research on Pulsating Beds. Processes 2025, 13, 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123902

Li D, Yuan D, Jiang H, Li Y, Hong K. A Comprehensive Review of Research on Pulsating Beds. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123902

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Deqi, Di Yuan, Heng Jiang, Yanjiao Li, and Kun Hong. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review of Research on Pulsating Beds" Processes 13, no. 12: 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123902

APA StyleLi, D., Yuan, D., Jiang, H., Li, Y., & Hong, K. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Research on Pulsating Beds. Processes, 13(12), 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123902