1. Introduction

With the continuous improvement of industrial intelligence levels, smart manufacturing technology has become the core driving force for promoting the transformation and upgrading of traditional manufacturing industries [

1]. As a typical process industry, cement manufacturing relies heavily on the accurate control of the kiln head temperature of the rotary kiln during its production process, which is directly related to the stability of the calcination process, the consistency of clinker quality, and the optimization of system energy efficiency. Therefore, implementing real-time monitoring and dynamic optimal control of the kiln head temperature is of crucial significance for improving enterprise production efficiency and realizing closed-loop management of smart manufacturing.

Currently, the modeling methods for the operation process of rotary kilns are mainly divided into two categories: numerical simulation and data-driven methods [

2,

3]. Numerical simulation methods are based on the principles of heat transfer, dynamics, and thermodynamics. They discretize the internal space of the kiln into grid units, establish and solve combustion models, drying models, and mass balance models [

4,

5,

6]. Although this method can calculate the kiln head temperature with high precision, the production process of the rotary kiln involves processes such as gas–solid two-phase flow, pulverized coal combustion, and unsteady heat transfer, which exhibit strong nonlinearity, large time delay, and strong multi-variable coupling characteristics [

7,

8]. These characteristics result in substantial computational resources required for model solving and a long convergence time, making it difficult to meet the requirements of real-time monitoring.

Data-driven modeling methods can establish mathematical models for the rotary kiln operation process by learning from the historical operational data of rotary kilns using machine learning techniques. Yin et al. [

9] proposed an adaptive data-driven soft sensor method: by integrating moving window technology and the just-in-time learning (JITL) mechanism into the partial least squares regression (PLSR) algorithm, they developed two adaptive soft sensors for real-time monitoring and prediction of the zinc rotary kiln temperature. This method effectively copes with dynamic temperature changes and eliminates the time delay issue of traditional models. Wang et al. [

10] put forward a rotary kiln temperature field prediction method that combines computational fluid dynamics (CFDs) with machine learning. They generated a dataset covering 625 operating conditions via CFD to train the prediction model; while maintaining prediction accuracy, this method reduced the computation time from 2 to 3 weeks (of traditional methods) to 10 s, with a significant decrease in prediction error.

Zheng et al. [

11] proposed an optimization method for NO

x emissions in the cement calcination process based on improved just-in-time learning Gaussian mixture regression (JITL-GMR). By optimizing sample selection through a spatiotemporal similarity strategy and combining the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm to dynamically optimize operating parameters, this method significantly reduced the NO

x emission level at the kiln tail. Although the aforementioned methods can describe the rotary kiln operation process to a certain extent, they fail to capture deep-seated features due to the inherent limitations of traditional machine learning [

12]. Consequently, they exhibit poor learning capabilities for the process data of rotary kilns, which are characterized by strong nonlinearity and long time delays.

With the development of deep learning [

13] technology, this approach has attracted the attention of numerous researchers. Deep learning can capture deep-seated features through large-scale datasets and thereby construct corresponding mathematical models, and it has been widely applied in various industrial production processes [

14,

15,

16]. In terms of rotary kiln monitoring, Zheng et al. [

17] proposed a hybrid modeling strategy integrating process mechanism and recurrent neural networks (RNNs). By compensating for the residence time inside the kiln through a time-delay mechanism and introducing attention mechanism-enhanced long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to capture nonlinear time-varying characteristics, this strategy significantly improved the accuracy and robustness of dynamic modeling for cement rotary kilns. Xu et al. [

18] developed a graph neural network (GNN) model. By optimizing unstructured grid computation using the Cleary–Luby–Jones–Plassmann graph topology coarsening algorithm, this model maintained high precision in predicting the two-dimensional temperature field of the rotary kiln while improving computational efficiency by three orders of magnitude compared with traditional CFD methods. Thus, it provides a new approach for real-time temperature monitoring and energy efficiency optimization of rotary kilns. Li et al. [

19] proposed a multi-parameter collaborative optimization method based on data-driven models and improved particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithms. By using a sparse autoencoder-based bidirectional LSTM network to predict combustion status and NO

x emissions, this method achieved high stability and low-cost control of NO

x emissions during waste incineration. Wang et al. [

20] constructed a time series prediction model (nonlinear autoregressive with exogenous inputs-time convolutional network, NARX-TCN) that integrates inlet flue gas, process control parameters, and pollutants. By dynamically predicting the next-moment SO

2 concentration through nonlinear autoregression and time convolutional networks, and by reducing the flue gas pressure at the absorber inlet or increasing the pressure in the concentration section, this model effectively improved desulfurization efficiency and provided a data-driven solution for real-time regulation of industrial parameters.

To address the challenges of strong multi-variable coupling and temporal dynamic prediction for the clinker rotary kiln head temperature, this paper proposes a heterogeneous ensemble model integrating Relief feature selection and optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF. By leveraging multi-variable feature selection and an adaptive error-oriented weight fusion mechanism, the model enhances prediction robustness, providing a new paradigm for temporal prediction of complex industrial time series parameters. The main innovations of this paper are as follows:

(1) A Relief multi-variable feature selection method adapted to industrial scenarios is proposed. Based on multi-source parameters of the rotary kiln, the method calculates the contribution of features to the differences in target values of neighboring samples. It screens out high-contribution features, effectively filtering noise and temporal redundant information, improving the discriminability of input features, and enhancing the model’s anti-interference capability from the data source.

(2) A three-layer heterogeneous ensemble architecture of CNN-BiLSTM-RF is constructed. CNN-BiLSTM extracts spatial coupling features of multiple variables and captures bidirectional temporal dependencies, taking both historical influences and future trends into account. Meanwhile, RF performs dynamic decision-making based on feature weights, overcoming the limitations of single models. The R2 of the proposed model on the test set reaches 0.87482, representing an increase of up to 15.5% compared with single models.

(3) Gaussian probabilistic intervals are constructed to achieve reasonable quantification of uncertainty, supporting reliable future trend prediction and thus providing a basis for decision-making.

The temporal forecasting model proposed in this study holds broad application potential in industrial scenarios. For general industrial time series forecasting tasks—such as predicting parameters in chemical reaction processes, monitoring equipment status in smart manufacturing, and forecasting loads in energy systems—the integrated feature selection, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) denoising, and adaptive weighted fusion strategies effectively address common challenges in industrial data, including high noise levels, feature redundancy, and nonlinear correlations. By accurately capturing both spatial correlations and bidirectional temporal dependencies in time series data, the model provides reliable support for real-time industrial process control, fault warning, and optimized decision-making. This contributes to reducing energy consumption, improving product quality consistency, and offers valuable technical references for intelligent industrial upgrading.

3. Optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF Time Series Framework

3.1. Overall Model Architecture

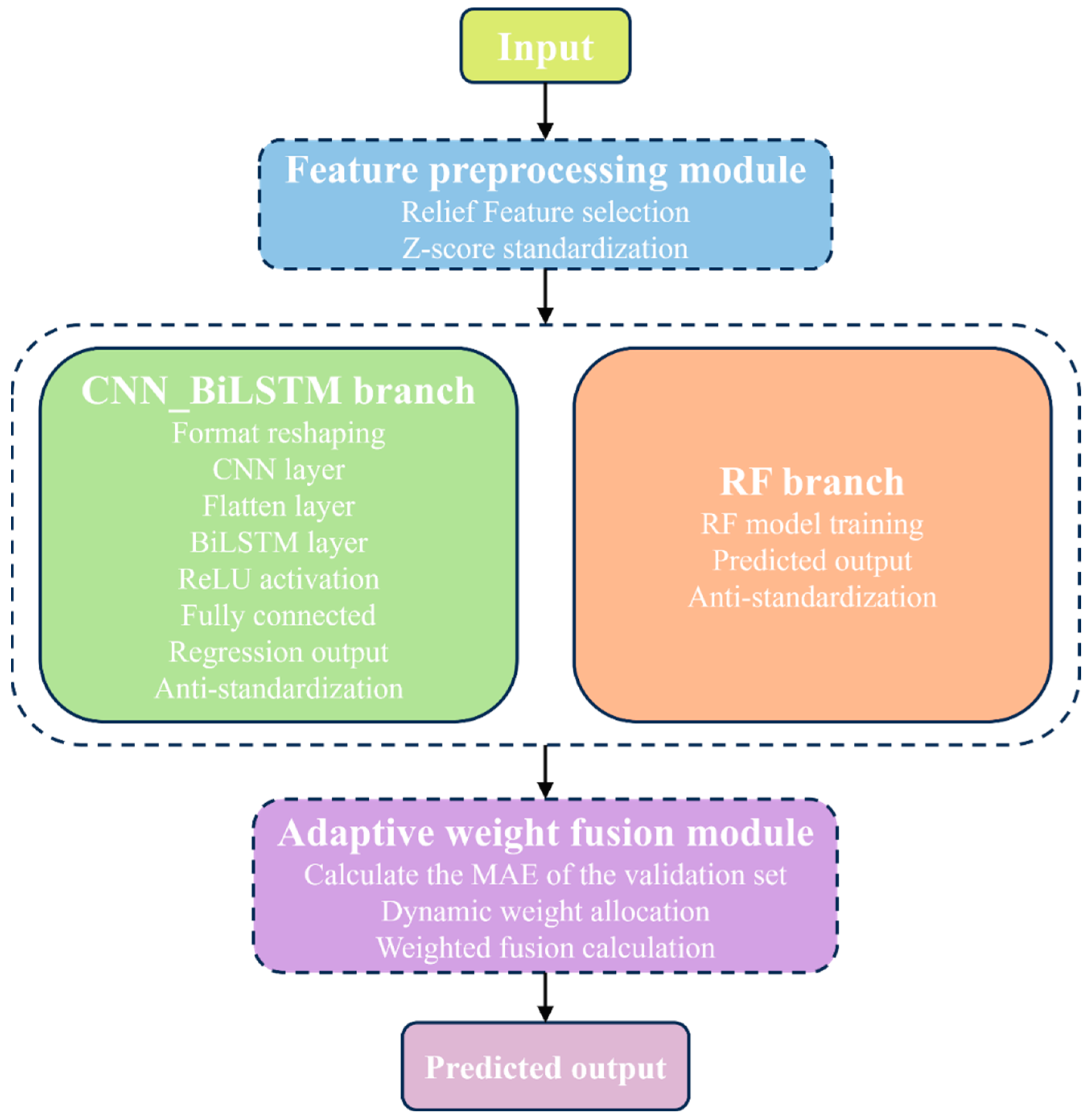

The optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF model is mainly composed of two parts: a deep feature extraction layer (CNN-BiLSTM) and a dynamic decision fusion layer (RF), and is optimized using the metaheuristic algorithm. Specifically, the CNN-BiLSTM module consists of an input layer, convolutional layer, batch normalization layer, ReLU activation layer, max-pooling layer, Flatten layer, BiLSTM layer, fully connected layer, and regression output layer.

Unlike traditional machine learning models such as XGBoost [

21], the proposed overall model adopts a phased modeling approach, coordinating parameters of multiple modules to perform feature extraction and time series modeling. The architecture of the overall model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Feature Preprocessing Module: The input data first undergoes Relief feature selection to identify and retain core features strongly relevant to the prediction target. Subsequently, Z-score normalization is applied to eliminate the influence of varying measurement scales.

CNN_BiLSTM Branch: The processed data is reshaped to fit the convolutional input requirements. A CNN layer is employed to extract local spatial correlations and short-term patterns. The resulting feature maps are then flattened and fed into a BiLSTM layer to capture bidirectional long-term temporal dependencies. The output is passed through a ReLU activation function and a fully connected layer for regression, followed by denormalization to restore the original data scale.

RF Branch: A Random Forest model is trained directly on the preprocessed data. Its predictions are similarly denormalized to the original scale.

Adaptive Weight Fusion Module: The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of each branch on the validation set is calculated. Fusion weights for the two branches are dynamically assigned based on the inverse of their respective MAE values, favoring the more reliable branch. The final prediction is obtained as the weighted sum of the two branches’ outputs.

Prediction Output Module: This module delivers the adaptively fused final prediction.

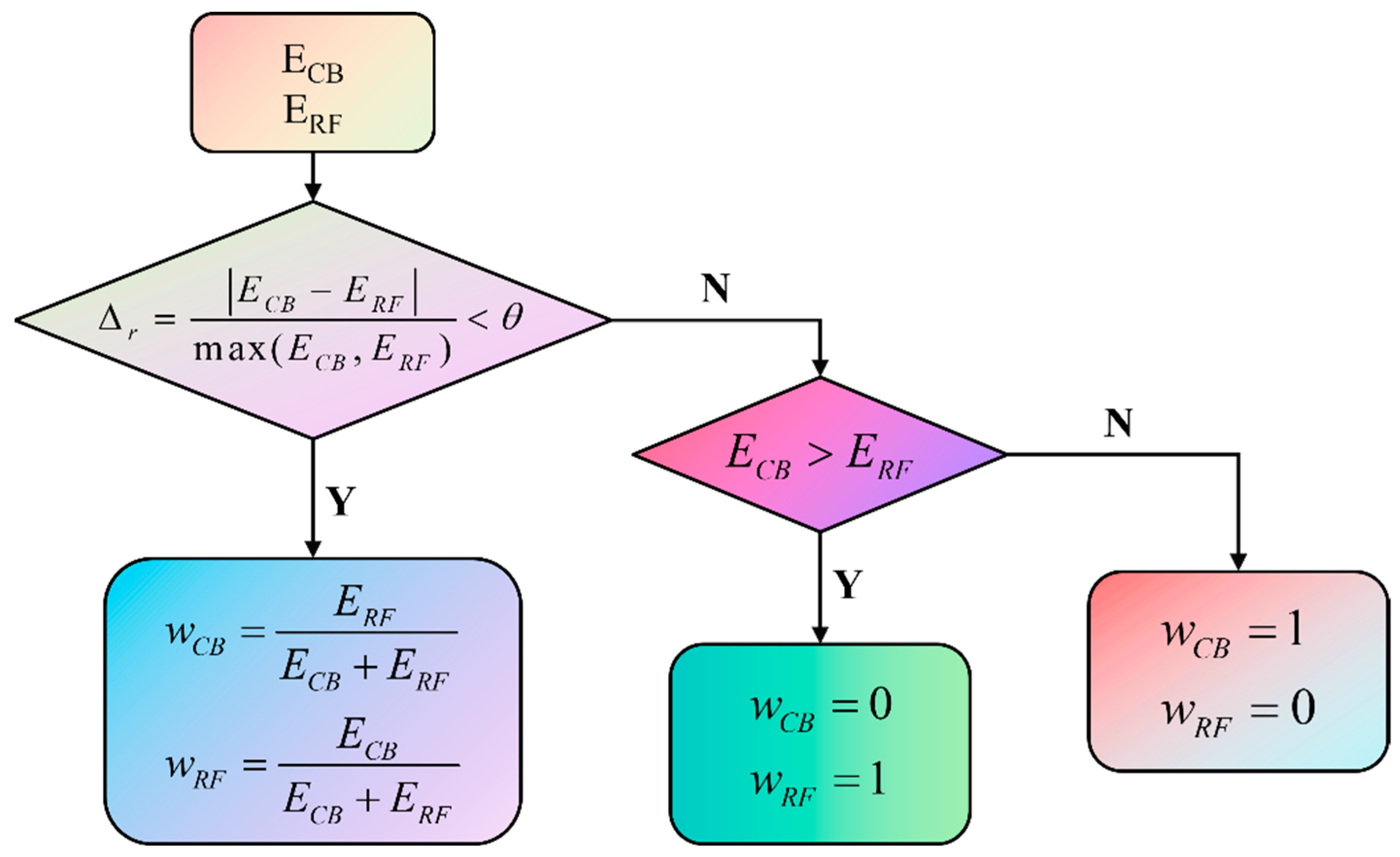

3.2. Adaptive Weight Allocation Mechanism

After initializing the optimized hyperparameters, setting the upper and lower bounds of the optimized parameters, and determining the number of optimization iterations, the meta-heuristic optimizer MMGO (Mapping mountain gazelle optimizer) algorithm [

22] was used to search for the optimal hyperparameters of the model. Subsequently, the errors of the two sub-models (CNN-BiLSTM and RF) on the validation set were recorded, and the relative error difference

was employed to evaluate the performance of different sub-models. The corresponding formula is as follows:

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of CNN-BiLSTM and RF on the validation set was calculated to ensure that weight allocation was based on model generalization ability rather than the fitting effect on the training set. Then, the appropriate weights were selected and allocated by judging the errors of the two sub-models on the validation set. The allocation process is shown in

Figure 2.

In

Figure 2,

represents the MAE of the CNN-BiLSTM model,

denotes the MAE of the Random Forest model,

refers to the weight assigned to the CNN-BiLSTM model,

indicates the weight assigned to the Random Forest model, and

is the decision threshold, which is set to 0.1 in this study.

After calculating and , their absolute difference is compared against the threshold . If the difference is less than or equal to , the weights and are allocated proportionally based on the respective errors. Conversely, if the difference exceeds , the model with the smaller error is assigned full weight, effectively disregarding the model with the larger error.

After weight allocation, the de-normalized predicted values of the two sub-models were weighted and summed according to the allocated weights to obtain the final prediction result. Dynamically allocating the weights of the two sub-models based on relative error differences to achieve advantage complementarity is the key feature that distinguishes this model from traditional single models.

3.3. Loss Function

For CNN-BiLSTM, to avoid the impact of extreme deviations on its performance, special attention needs to be paid to the stable convergence of the model itself. Therefore, the mean square error (MSE) is adopted as its loss function, and the formula is as follows:

where

represents the sample size,

is the true value of the

i-th sample,

is the model prediction value of the

i-th sample.

However, as a decision tree-based ensemble model, RF requires greater focus on the overall characteristics of the data. The MAE imposes a linear penalty on outliers, which better facilitates minimizing the error of child nodes and thus improves model performance. Consequently, MAE is selected as the loss function for RF, with the formula given below:

where

represents the sample size,

is the true value of the

i-th sample,

is the model prediction value of the

i-th sample.

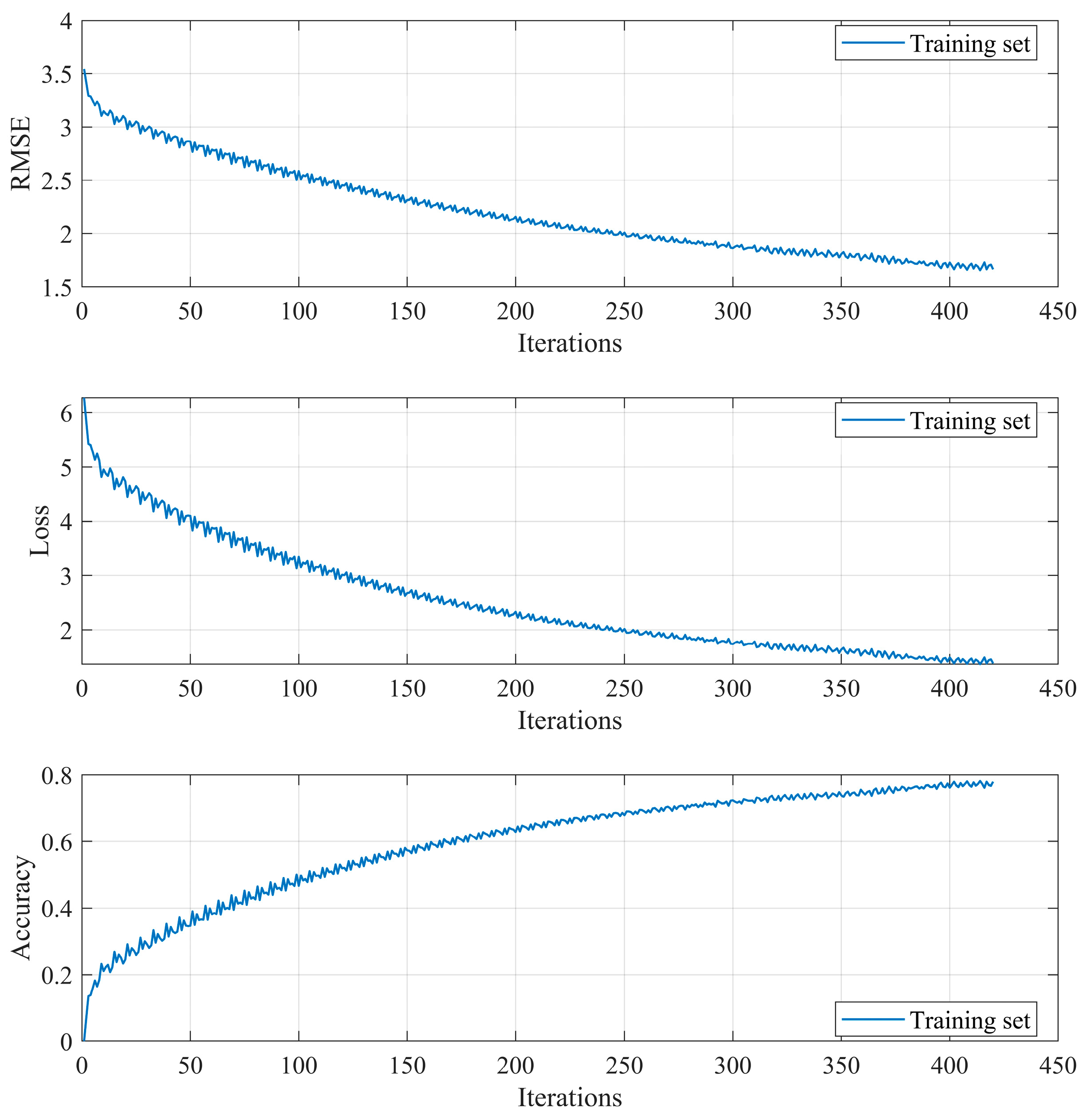

Figure 3 clearly illustrates the key dynamics of the model’s learning process, specifically the evolution of training performance in terms of RMSE, Loss, and Accuracy. The curves demonstrate a favorable convergence behavior throughout training.

3.4. Probabilistic Interval Prediction

Time series data typically exhibit a dynamic nature, uncertainty, and susceptibility to noise interference. The core advantage of probabilistic interval prediction over traditional point prediction lies in its ability to quantify uncertainty, enabling better adaptation to data fluctuations and interference, thereby providing a basis for decision-making.

In this study, a Gaussian-based probabilistic interval prediction method is employed, which leverages the normal distribution assumption and statistical characteristics of errors for calculation. According to the target confidence level, the uncertainty is estimated using the quantile function of the normal distribution and the prediction errors of the validation set, which is used to determine the width of the confidence interval. The calculation formulas for the upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval are as follows:

where

is the point prediction value of the

i-th sample,

is the quantile corresponding to the confidence level

,

is the standard deviation of the validation set error,

is the sample size of the validation set.

As the sample size decreases, the interval becomes wider to address uncertainty. By dynamically adjusting the interval width, the probabilistic interval better aligns with the actual characteristics of the data.

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Relief Feature Selection

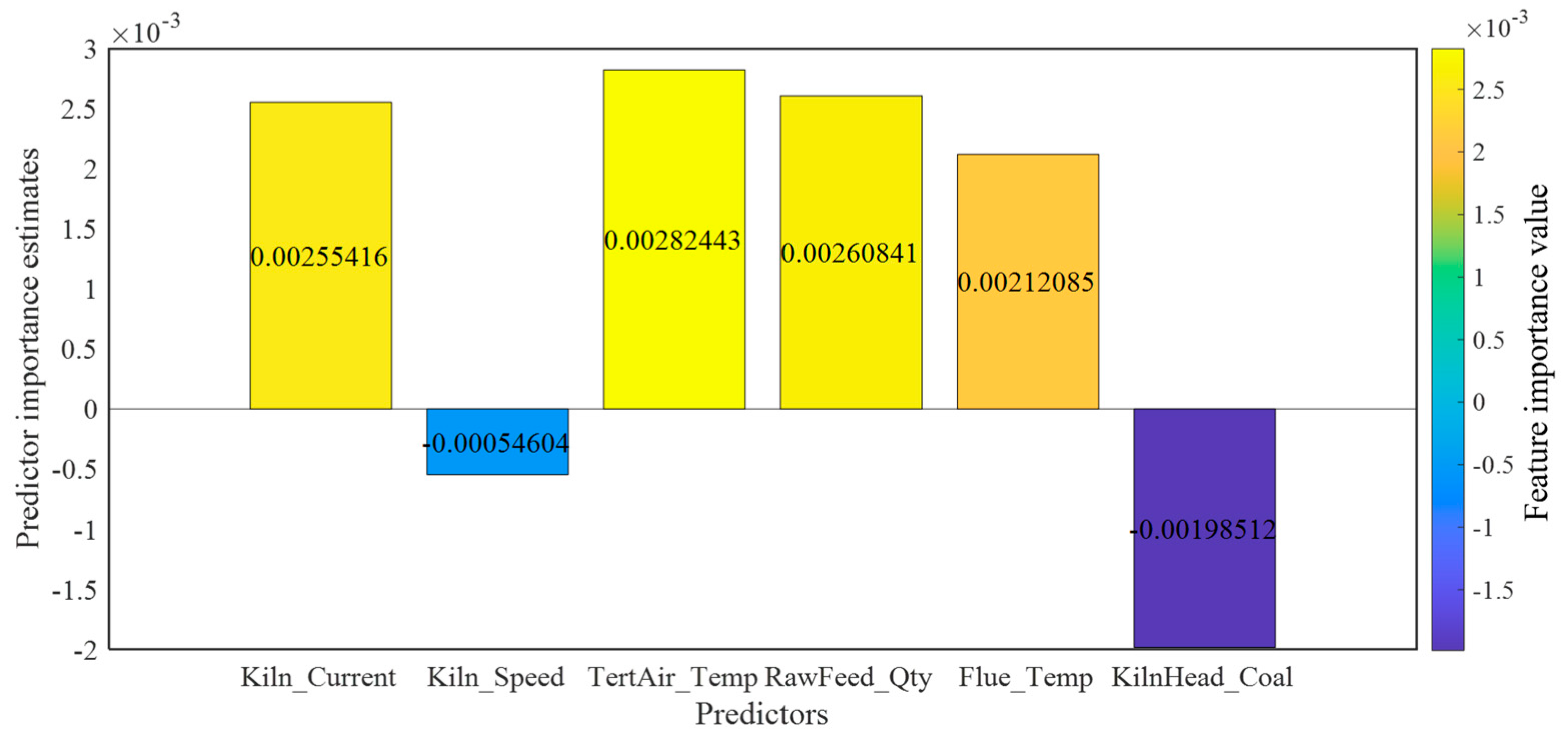

As shown in

Figure 4, the Relief algorithm ultimately screened three core features: tertiary air temperature (TertAir_Temp), raw meal feed rate (RawFeed_Qty), and rotary kiln current (Kiln_Current). This result is highly consistent with the thermal balance mechanism of the rotary kiln calcination process, and the role and importance of each feature are analyzed as follows:

Tertiary air temperature (TertAir_Temp): As a key parameter of the combustion-supporting air in the kiln, it directly affects fuel combustion efficiency. Its fluctuations are transmitted to the kiln head temperature, making it a core characteristic variable of the heat input process. It has the highest importance because its fluctuation pattern in the dataset exhibits the strongest instantaneous correlation with the kiln head temperature, stably reflecting changes in heat input.

Raw meal feed rate (RawFeed_Qty): As an input parameter of the heat-absorbing carrier, it is directly related to heat consumption and serves as a core operational variable for thermal balance adjustment. It ranks second in importance: as a manually regulated slow variable, its lagged correlation with temperature is stable in time series data. However, due to its low adjustment frequency, its contribution is slightly lower than that of tertiary air temperature.

Rotary kiln current (Kiln_Current): It indirectly reflects the material filling rate and movement state inside the kiln. An abnormal increase in current often indicates risks of ring formation or material blockage, which affects the kiln head temperature by changing the flame shape, making it an important early warning indicator for operational stability. Its slightly lower importance is due to its nonlinear impact on temperature, but it is irreplaceable in capturing non-thermal interference factors.

These three features together form a characteristic system covering heat input, heat consumption, and operational stability, encompassing several key dimensions that influence the kiln head temperature.

4.2. Model Performance Analysis

4.2.1. Fitting Performance

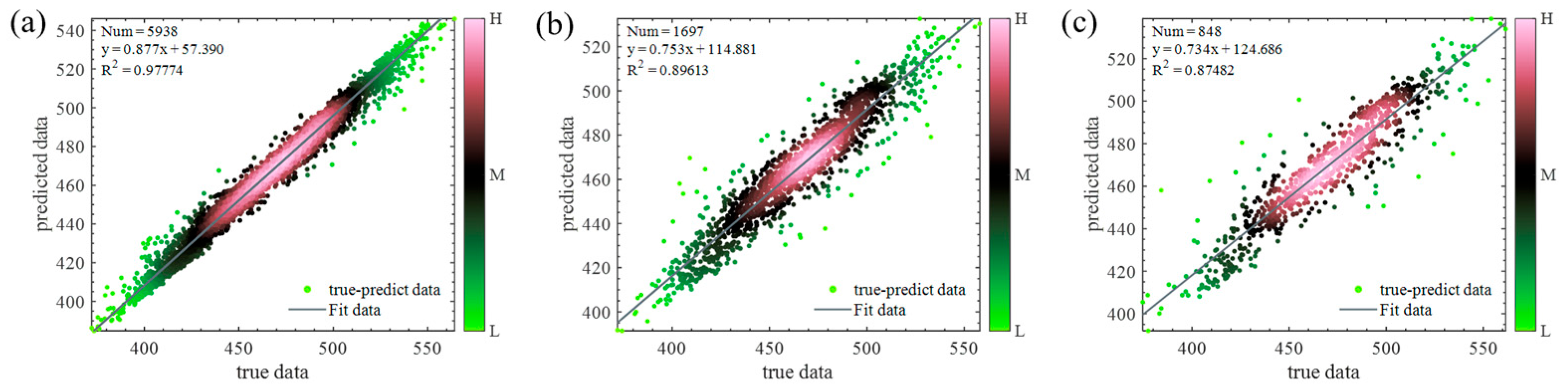

Figure 5a presents the density plot of the training set, which exhibits an excellent fitting performance. The dense color area is concentrated around the fitting line, indicating that the model has learned sufficiently from the training set and can capture the inherent patterns of the data.

Figure 5b shows the density plot of the validation set, where the data density is slightly lower than that of the training set. In contrast, the fitting performance of the test set (

Figure 5c) is slightly inferior to that of the training and validation sets, but it still maintains a high standard, demonstrating the model’s strong overall generalization ability.

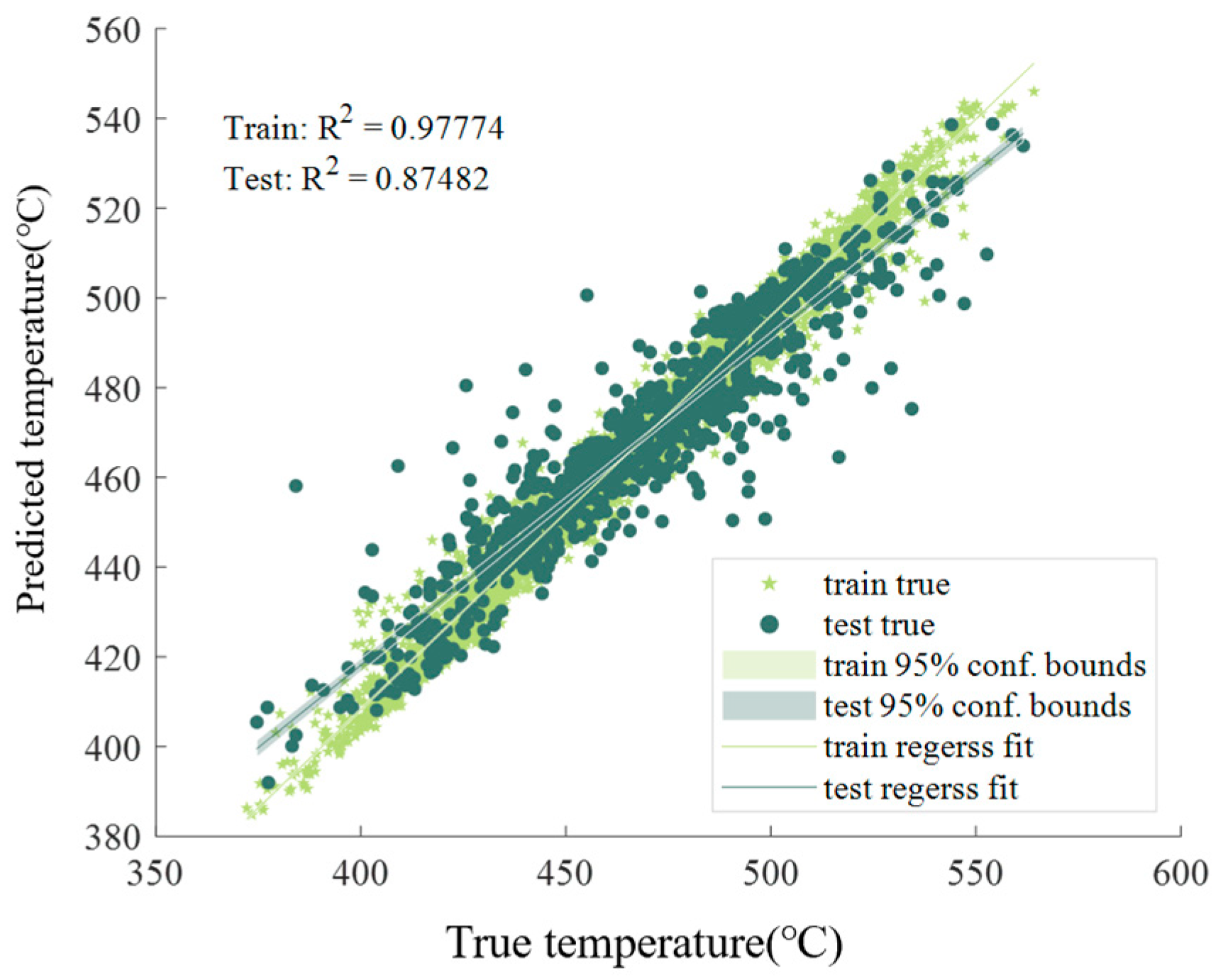

Figure 6 displays the joint density plot of the training set and test set. The true values of the training set cluster around the training fitting line, showing a narrow-band distribution along the line, which reflects the model’s high prediction accuracy. Additionally, the bandwidth of the 95% confidence interval for the training set is relatively narrow, indicating lower prediction uncertainty of the model for the training data. In contrast, the fitting deviation of the test set is larger than that of the training set, and the bandwidth of the 95% confidence interval for the test set is wider, resulting in higher prediction uncertainty for the test data. This is because the test data are new and not involved in model training, making error fluctuations more difficult to predict; thus, a wider interval is required to cover the true values. Overall, the model still maintains good fitting performance and strong generalization ability.

4.2.2. Prediction Capability

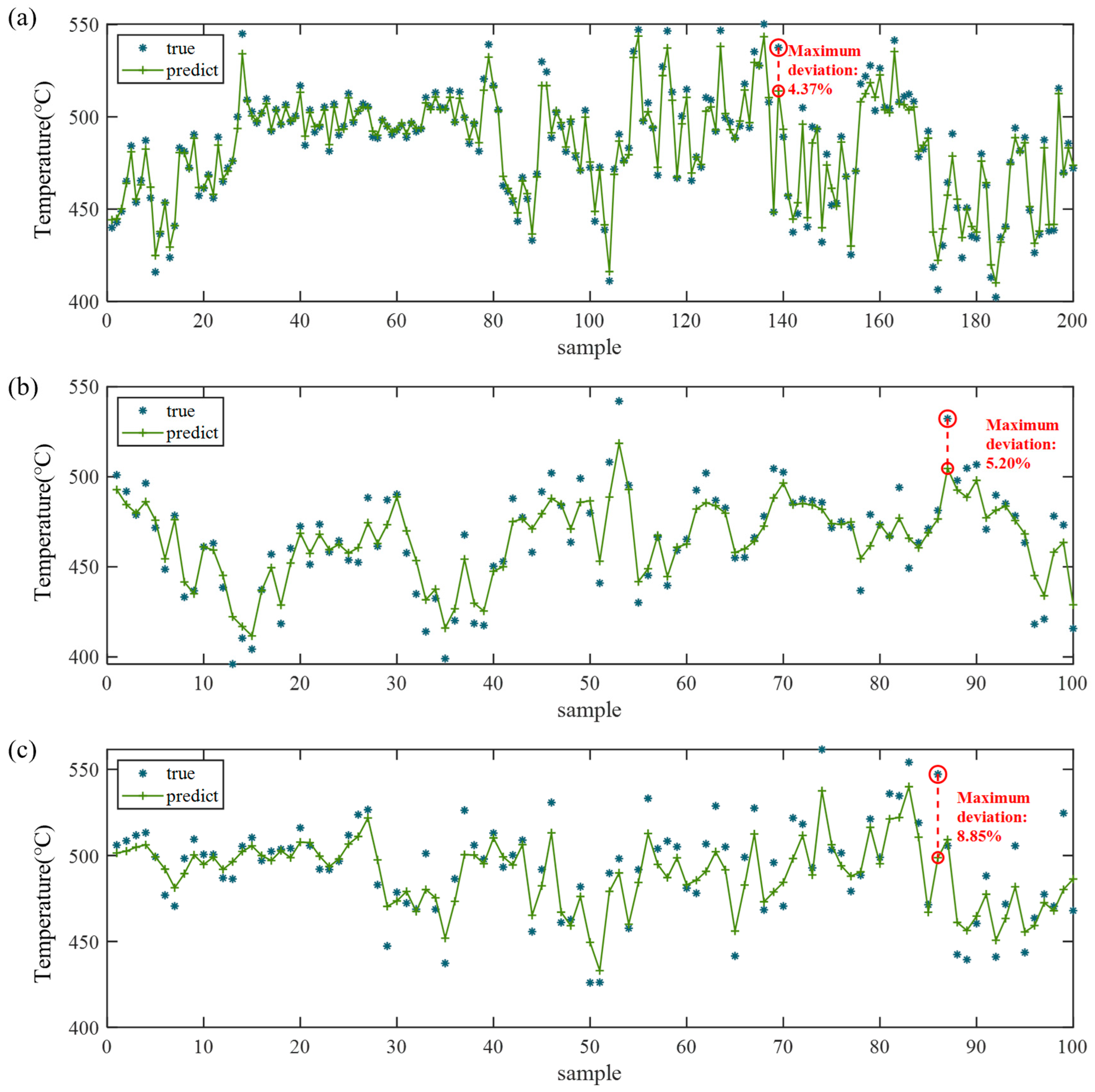

Figure 7 illustrates the comparison curves between the predicted results of the optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF model and the true values for partial data in the training set, validation set, and test set, respectively.

Specifically, in

Figure 7a (training set), the green predicted curve is consistent with the overall trend of the blue true value scatter points. Even in high-frequency fluctuation intervals, the predicted curve can oscillate and rise or fall accurately following the true values, exhibiting almost no significant lag or deviation. This indicates that the model has fully learned the fluctuation patterns of the time series data on the training set.

In

Figure 7b (validation set), the predicted curve still captures the overall trend of the true values, demonstrating that the model has partially transferred the patterns learned from the training process to the validation data.

In contrast,

Figure 7c (test set) shows that the predicted curve can roughly follow the core trend of the true values, which verifies the generalizability of the core time series patterns learned by the model. However, local deviations increase slightly, which reflects the novelty of the test data (not involved in training) and may also be attributed to data distribution differences or noise that enhance prediction uncertainty. Nevertheless, the model’s predicted values still track the variation trend of the true values well, and maintain high prediction accuracy even in regions with large temperature fluctuations—confirming the model’s strong adaptability and generalizability.

4.2.3. Model Performance Comparison

The performance of the optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF model was compared with that of three single models (CNN, BiLSTM, and RF). The performance comparison results of all models on the test set are presented in

Table 1.

As shown in

Table 1, the optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF model outperforms the other comparative models in all evaluation metrics. Compared with the single CNN, BiLSTM, and RF models, the optimized model achieves a 27.7% reduction in Mean Absolute Error (MAE), a 27.4% reduction in Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), a 47.8% reduction in Mean Squared Error (MSE), a 27.8% reduction in Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and a 15.5% increase in coefficient of determination (R

2). These results indicate that the optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF model can effectively improve prediction performance and has obvious advantages in capturing complex dependencies and dynamic features among multiple variables, thus verifying the effectiveness of the heterogeneous ensemble.

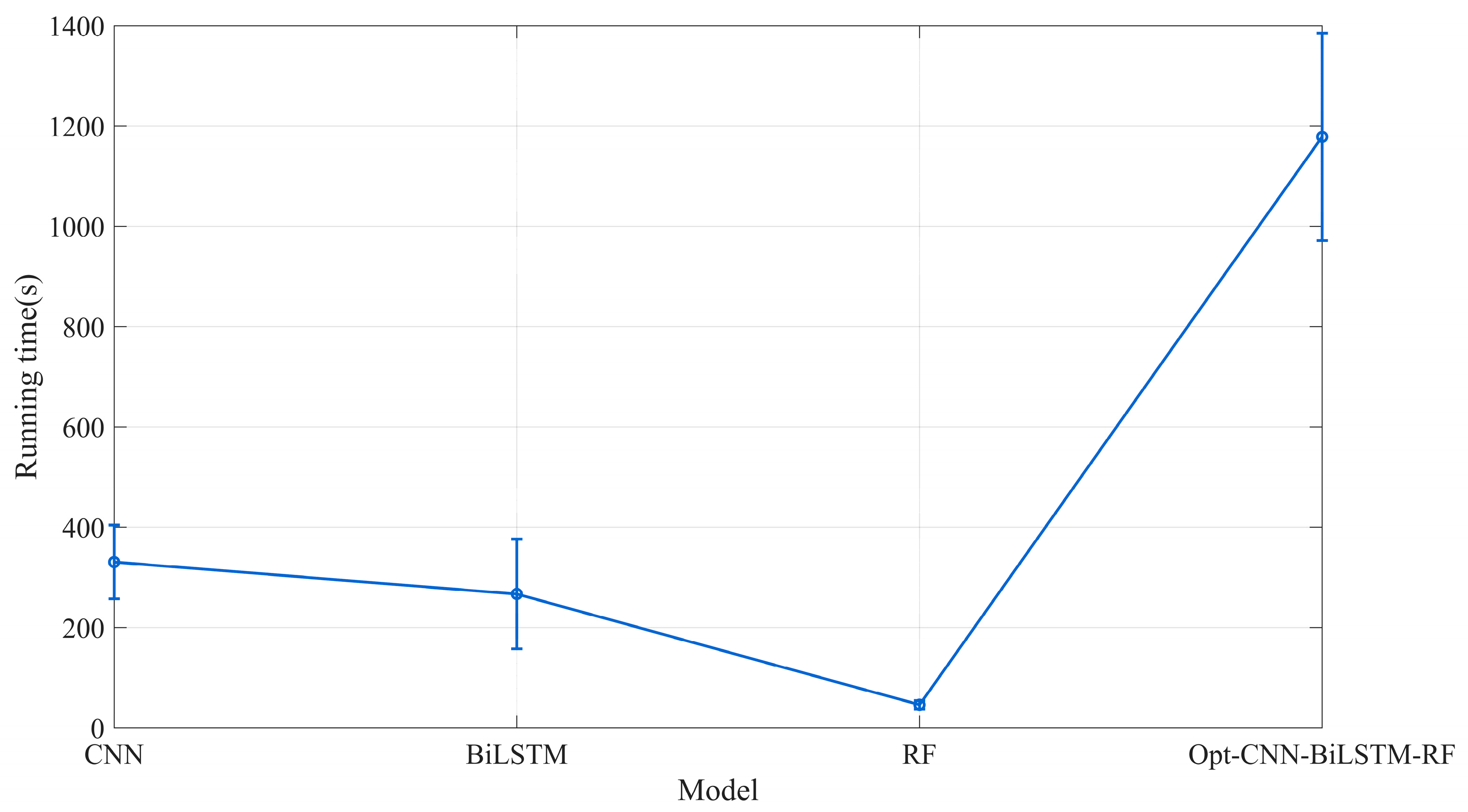

Figure 8 presents a comparison of the average runtime across the four models. The results indicate that the enhanced performance of the hybrid model is accompanied by a notably higher computational overhead. Therefore, model selection requires a deliberate consideration of the trade-off between predictive capability and running efficiency.

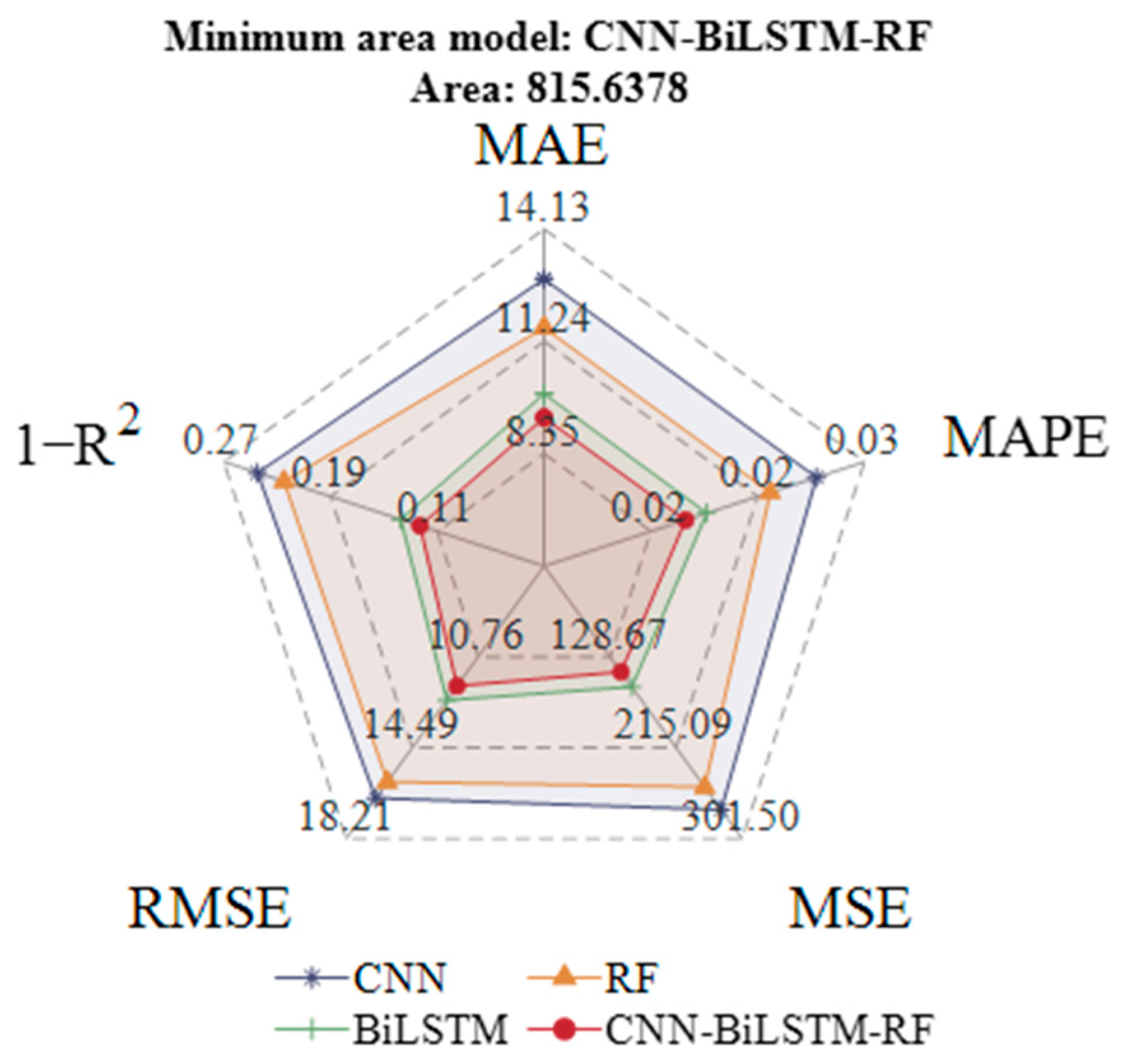

To more intuitively reflect the performance differences between models, the evaluation metrics were visualized using a radar chart, as shown in

Figure 9.

Figure 9 compares the performance of CNN, BiLSTM, RF, and the optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF across five core model metrics (MAE, MAPE, MSE, RMSE, and 1 − R

2), where smaller values indicate better performance for all metrics. It can be easily observed from the chart that the performance of each model can be judged by the area enclosed by its metric values. Among all models, the optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF encloses the smallest area and outperforms the single models in all metrics, confirming its optimal performance. This verifies the effectiveness of the proposed model in time series prediction tasks, as it balances both prediction accuracy and generalizability.

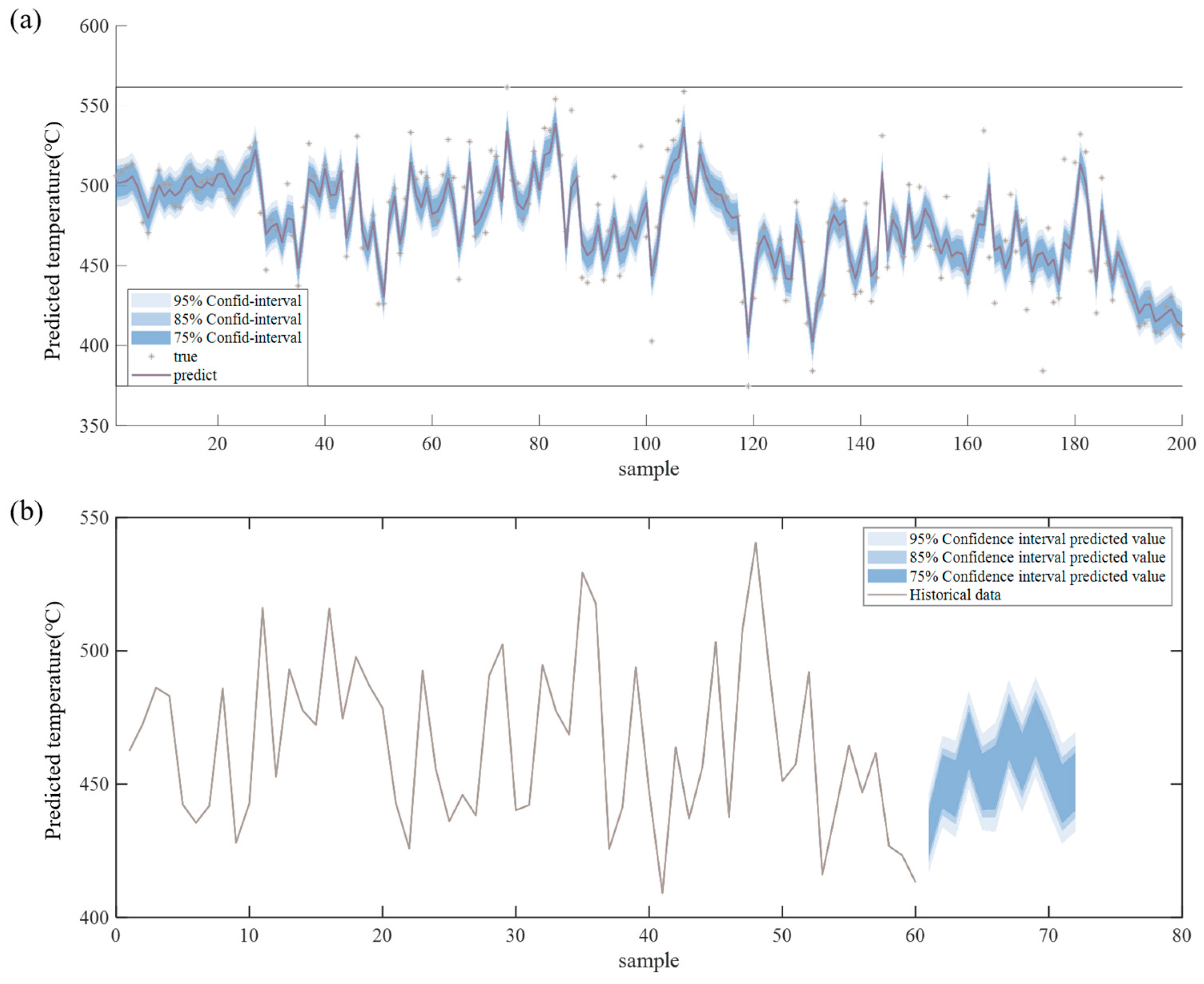

4.3. Probabilistic Interval Time Series Prediction

Figure 10a presents the multi-confidence level time series prediction fitting comparison chart, which includes three confidence intervals (75%, 85%, and 95%) distinguished by filled bands ranging from light blue to dark blue. Consistent with statistical principles, the higher the confidence level, the wider the interval bandwidth. Notably, most true values fall within each confidence interval, indicating that the uncertainty estimation of the model is reasonable. Additionally, the fitted curve of predicted values aligns well with the overall distribution trend of true values and can even capture local small-scale fluctuations—fully demonstrating the model’s high prediction accuracy for training data points.

Figure 10b shows the future trend prediction confidence interval chart. The initial shape of the future prediction interval connects naturally with the tail trend of historical data, the fluctuation characteristics of historical data near the 60th sample point are inherited by the initial shape of the prediction interval, which proves that the model considers the continuity of historical trends during extrapolation.

Furthermore, the bandwidth of the future interval does not expand excessively as the prediction step increases, and the oscillation pattern inside the interval is similar to the actual fluctuation characteristics of historical data. This reflects the model’s ability to reasonably quantify future uncertainty: it not only inherits historical patterns but also covers potential risks through the designed intervals, providing reliable decision support for future operational adjustments of the rotary kiln.

The probabilistic interval forecasts generated in this study can be directly applied to quantify risks in industrial control decisions. For instance, in a kiln temperature control scenario, the predictions with a 95% confidence interval quantify the risk range of “actual temperature deviating from the predicted value.” If the prediction interval encompasses the process-allowed temperature threshold, the associated decision risk is low, and current control parameters can be maintained. Conversely, if the interval exceeds the threshold, control strategies must be adjusted based on the interval’s characteristics—such as increasing the monitoring frequency when the interval is too wide, or preemptively raising the temperature when the lower bound falls below the threshold. This approach provides a quantifiable basis for enhancing the robustness of industrial control systems.

4.4. Discussion

Feature Selection: The Relief algorithm was employed to identify and retain core features strongly correlated with the prediction target, thereby eliminating redundant information and reducing model computational complexity as well as the risk of overfitting.

Data Preprocessing: Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) was applied to effectively separate the target signal from noise, enhancing data quality and providing cleaner temporal features for model learning.

Model Architecture: The CNN component extracts local spatial correlations within the temporal data through convolutional operations, capturing underlying relationships between features at adjacent time steps while mitigating interference from irrelevant information.

The BiLSTM layer utilizes both forward and backward LSTM units to simultaneously capture past and future dependencies in the time series data, adapting to the dynamic characteristics of industrial processes.

The RF model, based on ensemble learning with multiple decision trees, enhances the model’s capacity to fit nonlinear relationships, reduces overfitting risks associated with single models, and provides robust decision support for the fused framework.

Fusion Strategy: An adaptive weighting mechanism, based on the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on the validation set, dynamically allocates weights to the two model branches. This approach leverages the strengths of each individual model while compensating for its respective limitations, thereby achieving overall performance improvement.

5. Conclusions

To address the kiln head temperature prediction problem of rotary kilns, this study proposes an optimized CNN-BiLSTM-RF time series prediction framework based on Relief feature selection and adaptive weight integration. Through preprocessing of industrial data and feature engineering, rich dynamic features are extracted; by introducing an adaptive weight mechanism, the proposed model effectively enhances the ability to capture key variables and long-distance dependencies. Experimental results show that this method outperforms traditional machine learning models and existing deep learning models in prediction accuracy, providing effective technical support for the stable operation of rotary kilns. Specific conclusions are as follows:

(1) Data preprocessing and feature selection ensure data validity and feature specificity, laying a solid foundation for subsequent model training.

(2) The proposed fusion strategy integrates the advantages of CNN, BiLSTM, and RF: CNN captures spatial coupling features, BiLSTM models bidirectional temporal dependencies, and RF enhances robustness—collectively significantly improving prediction accuracy.

(3) The introduction of an adaptive weight mechanism enables the model to dynamically adjust the contribution of each sub-model according to data characteristics, thereby enhancing its adaptability to dynamic industrial data.

(4) Gaussian probabilistic intervals are utilized to achieve reasonable quantification of prediction uncertainty, which not only quantifies potential risks but also supports reliable prediction of future temperature trends.

(5) The error variation from the training set to the test set and the comparison of multiple evaluation metrics verify that the model balances both fitting accuracy and generalization ability, meeting the requirements of practical industrial applications.

Limitations of This Study:

The limited dataset size may lead to insufficient learning of temporal features under extreme operating conditions, and the model’s generalization capability requires further validation.

Dependence on Hyperparameters: Key hyperparameters, such as the number of IMFs in VMD and the size of CNN convolutional kernels, require manual adjustment based on empirical experience. The current framework lacks an adaptive optimization mechanism for these parameters.

Simplistic Fusion Strategy: The fusion weights are assigned solely based on the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) metric. This approach does not incorporate other statistical characteristics of the predictions, such as variance or skewness, which could provide a more comprehensive basis for fusion.

Future Research Directions:

Automatic Hyperparameter Tuning: Future work will explore the integration of advanced optimization techniques, including Bayesian optimization and genetic algorithms, to automate the hyperparameter search process. This aims to enhance model performance while reducing reliance on manual intervention.

Multi-Metric Fusion Strategy: Subsequent research will focus on developing a more sophisticated fusion strategy. This involves constructing a weighted matrix that incorporates multiple metrics—such as variance and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)—to more effectively leverage the strengths of each constituent model and improve overall predictive robustness.

Incorporate interpretability techniques such as SHAP or Grad-CAM to visualize the decision-making process of the CNN-BiLSTM-RF model and quantify the contribution of key features to the predictions.

Expand the current single-target prediction to multi-target forecasting, thereby providing more comprehensive decision support for industrial control.