Abstract

The accelerating deterioration of the global environment underscores the urgent need to transition from the conventional fossil fuels to renewable energy, particularly the abundant solar energy. However, large-scale solar power integration could cause the severe grid fluctuations and compromise the operational stability. Existing studies have attempted to address this issue using hydrogen-based energy storage for peak shaving, but most suffer from low system efficiency. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a novel solar-driven integrated energy system (IES) for hydrogen production and combined heat and power (CHP) generation, in which advanced hydrogen storage technologies are employed to achieve the efficient system operation. The system couples four subsystems: parabolic trough solar collector (PTSC), transcritical CO2 power cycle (TCPC), Kalina cycle (KC) and proton exchange membrane electrolytic cell (PEMEC). Thermodynamic analysis of the proposed IES was conducted, and the effects of key parameters on system performance were investigated in depth. Simulation results show that under design conditions, the PEMEC produces 0.514 kg/h of hydrogen with an energy efficiency of 54.09% and an exergy efficiency of 51.59%, respectively. When the TCPC evaporator outlet temperature is 430.35 K, the IES achieves maximum energy and exergy efficiencies of 46.52% and 18.62%, respectively, with a hydrogen production rate of 0.51 kg/h. The findings highlight the importance of coordinated parameter optimization to maximize system efficiency and hydrogen productivity, providing theoretical guidance for practical design and operation of solar-based hydrogen integrated energy system.

1. Introduction

Recently, with the rapid development of society and economy, the energy demand is increasing rapidly. However, the traditional primary energy reserves are gradually depleting, failing to meet growing consumption needs. Moreover, fossil energy use causes severe environmental pollution and carbon emissions [1,2,3]. As a clean, non-polluting and renewable energy carrier, hydrogen offers a reliable solution to meet these challenges [4,5].

In hydrogen production, water electrolysis is one of the most suitable technologies for producing clean hydrogen, which was developed in the 18th century [6]. Using renewable energy to power electrolyzers for hydrogen production coupled with waste heat utilization effectively supports country energy conservation and carbon emission reduction goals. Solar collection system combined with transcritical CO2 power cycles (TCPC) can efficiently absorb and convert solar energy [7] to generate power and heat, which can directly drive the electrolyzer for hydrogen production. For low-temperature heat recovery, Kalina cycle (KC) exhibits the feature of boiling ammonia–water mixture under temperature variation compared to the pure mass circulation system, which can effectively reduce the losses caused by the heat transfer temperature difference in the evaporator and condenser to improve system efficiency and to match the low and medium temperature heat sources [8]. Yu et al. [9] proposed a novel geothermal energy recovery combining KC and TCPC, developing a thermodynamic model and optimizing system performance. Results indicated that the novel system significantly improved geothermal water, achieving a net power output of 2808 kW.

Electrolyzers can be divided into alkaline electrolyzer (AE), proton exchange membrane electrolysis cell (PEMEC), and solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC). PEMEC offers high hydrogen production rates, fast dynamic response, and strong adaptability to the fluctuations and intermittency of renewable energy sources, making it highly suitable for renewable energy generation [10]. Salari et al. [11] investigated an integrated photovoltaic and thermal system coupled with a PEMEC system and an organic Rankine cycle (ORC), conducting the thermodynamic modeling and performance analysis. The results revealed that using R134a as the ORC work fluid and water as the photovoltaic collector fluid achieved the best performance and the electrical efficiency was increased by 15.65% compared with the conventional PV system, with a maximum hydrogen production rate of 1.70 mol/h. Faeze et al. [12] integrated a high-temperature PEMEC (HT-PEMEC) with a concentrating solar tower and heat storage tank, achieving a hydrogen production efficiency of 23.1% and an IES exergy efficiency of 45%, respectively. The Rankine cycle efficiency was significantly improved by the integration of the proton exchange membrane electrolyzer.

Notably, more attention should be paid to H2 generation infrastructure because it involves high installation costs, safety regulations, and technical challenges such as dispensing flow rates and storage formats constrain large-scale rollout. Jayakumar et al. [13] emphasized a “corridor-first, demonstration-led” deployment strategy, combined with co-location at existing fuel retail or compressed natural gas stations as practical strategies to address the “chicken-and-egg” problem. Pilot projects in India illustrated the integration and safety lessons, highlighting the need for dedicated funding and incentives to reduce risk for private investors.

Green hydrogen from renewable-powered electrolysis directly supports SDG-7 by increasing the share of renewables in final energy consumption, enabling reliable off-grid services, and fostering investment in modern energy infrastructure. Jayakumar et al. [13] concluded policy instruments such as national roadmaps, targeted funds, and local electrolyzer manufacturing incentives are essential to accelerate both infrastructure deployment and the broader transition toward affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy access.

Based on the principle of energy cascade utilization and system integration theory, this study proposes a novel solar-driven IES for hydrogen production and cogeneration. The system utilizes solar energy as heat source and integrates the parabolic trough solar collector (PTSC) with the TCPC, KC and PEMEC. The proposed IES can simultaneously produce electricity, heat, hydrogen, oxygen, and other forms of energy. This study is structured as follows: Firstly, the novel IES is proposed, followed by the establishment of thermodynamic and exergy analysis model. Then, the system performance is subsequently evaluated and discussed in detail. Finally, the findings provide valuable insights and references for the development of renewable energy-based technologies for combined power and hydrogen production.

2. System Configuration

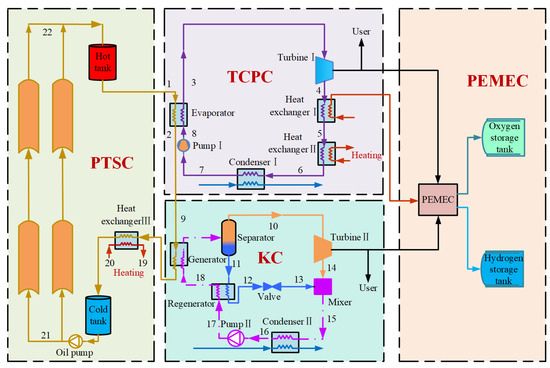

The integrated energy system includes four subsystems: PTSC, TCPC, KC, and PEMEC, as shown in Figure 1. A widely used thermal oil, Therminol-66, is selected as the heat transfer fluid (HTF) for the PTSC [14]. Therminol-66 absorbs solar heat in the PTSC and then flows into the hot tank for heat storage. The HTF then enters the TCPC evaporator to transfer heat to CO2 working fluid, after which it flows into the KC generator for additional power generation. The residual heat in HTF at the generator outlet continues to flow through the heat exchanger III to supply hot water to the user. The cooled HTF is stored in a cold tank before pumped back to the PTSC, completing the heat absorption cycle. In TCPC subsystem, the CO2 working fluid absorbs heat from Therminol-66 in the evaporator, becoming high-temperature and high-pressure supercritical CO2. It then enters turbine I to generate mechanical power, part of which is supplied to users, and the remainder powers the PEMEC for electrolysis and hydrogen production. The CO2 exiting turbine I becomes subcritical state at low temperature and pressure, and then passes through the heat exchanger I to exchange heat, where it preheats water to the operating temperature required by the PEMEC. Subsequently, it passes through heat exchanger II to heat cold water for space heating. The CO2 enters the condenser I to absorb the cold energy from the cold source and turns it into the subcooled CO2, then enters the pump I to pressurize it to supercritical pressure and then returns the evaporator, thereby completing the TCPC. In the KC, the basic solution of ammonia absorbs heat from the Therminol-66 in generator and enters a separator as a two-phase state mixture. In the separator, the basic solution is changed into ammonia-rich vapor and ammonia-poor solution. The ammonia-rich vapor enters turbine II to generate power, while the ammonia-poor solution enters the regenerator to preheat the basic solution, recovering heat and improving KC efficiency. After throttling, the ammonia basic solution mixes with exhaust steam from turbine II. The basic solution is condensed in condenser II, pressurized by pump II, preheated in the regenerator, and returned to the generator to complete the cycle. In the PEMEC, hydrogen and oxygen are produced via electrolysis using surplus power from turbine I and turbine II, then stored in gas storage unit. The PEMEC adopts a parallel cell configuration. Water electrolysis happens at the anode under the applied voltage and catalyst, generating oxygen, protons, and electrons. Driven by the electric field, protons migrate through the proton exchange membrane to the cathode, while electrons are conducted via the external circuit. At the cathode, protons and electrons recombine on the catalytic layer, undergoing a reduction reaction to produce hydrogen.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the solar-driven IES for hydrogen production and cogeneration application.

3. System Model and Validation

This part presents the energy and exergy models, the performance evaluation model, and the model validation employed in this study.

3.1. Energy Model

The PEMEC model was established based on the polarization curve. The following assumptions were made in the PEMEC modeling to simplify analysis [14,15]. And the design parameters of PEMEC are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operating conditions of PEMEC.

- (1)

- The PEMEC operates in steady-state thermodynamic conditions.

- (2)

- The temperature inside the PEMEC keeps uniform.

- (3)

- Each PEMEC unit has the same operating current and voltage.

- (4)

- Each PEMEC unit consists of bipolar plate, gas diffusion layer, catalyst layer, proton exchange membrane, etc.

- (5)

- The oxygen and hydrogen produced by the PEMEC are treated as ideal gases.

- (6)

- The PEMEC consists of serially connected electrolyzer units.

Table 2.

Constants used in the PEMEC model [15,16].

The electrochemical reactions occurring in the PEMEC and the total electrolysis reaction are expressed as [17]

The open circuit voltage of the PEMEC can be regarded as a function of temperature and pressure of the reactant water and the product oxygen [12,18]:

Due to the existence of various irreversible factors inside PEMEC, the actual operating voltage inside PEMEC is higher than the ideal voltage. The actual working voltage of a PEMEC unit is expressed as [12,16]:

where Uohm represents the ohmic loss voltage, V; Uact,a and Uact,c are the anode and cathode polarization voltages, V. These voltages are expressed by

where Jpem is the PEMEC current density, A/m2.

Assuming that PEMEC consists of single units in series, the total voltage of PEMEC is expressed as

The heat (Qpem) and power (Wpem) for the electrolysis reaction of PEMEC are expressed as

where ΔS represents the entropy change in the reaction process, kJ/(kg·K); I is the current of the PEMEC, A.

The operating current is

where Apem represents the effective area of the membrane electrode assembly, m2.

The molar flow rate of reactant water for PEMEC is calculated by [19]:

The molar flow rate of hydrogen and oxygen produced by PEMEC are

The TCPC system was modeled according to the thermodynamics laws. To simplify the analysis, the following assumptions were made.

- (1)

- The TCPC operates in steady-state conditions.

- (2)

- The pressure losses in components and pipes are negligible, and the entire system is adiabatic.

The main design parameters of TCPC are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main design parameters of TCPC system.

Considering each component of the system as an open thermal system with steady flow, the following equation is given:

where Qin is the heat input into the component, kW; m is the mass flow rate of the system working fluid, kg/s; hout is the specific enthalpy of the working fluid outlet in the component, kJ/kg; hin is the specific enthalpy of working fluid inlet in the component, kJ/kg; Wt is the system power output in the component, kW.

For each component, the following equation is given by

where mout is the mass flow rate of the outlet working fluid in each component, kg/s; min is the mass flow rate of the inlet working fluid in each component, kg/s.

The specific modeling equations for each component are shown below (numerical subscripts represent state points) [20].

The equations for the TCPC evaporator and condenser are given by

The isentropic efficiency of TCPC turbine is given by

where h4s represents the specific enthalpy at the working fluid outlet in the case of reversible adiabatic of the turbine, kJ/kg.

The external TCPC power output is calculated as

The efficiency of heat exchangers is expressed as

where Th,in represents the thermodynamic temperature of the fluid on the high temperature fluid side, K; Th,out represents the thermodynamic temperature of the fluid flowing out of the heat exchanger on the high temperature fluid side, K; Tl,in represents the thermodynamic temperature of the fluid on the low temperature fluid side, K. The heat exchanger is the recuperative heat exchanger.

The isentropic efficiency of TCPC pump is given by

where h8s is the specific enthalpy of the pump at the fluid outlet, kJ/kg.

TCPC pump power consumption is expressed as

The net external power output of TCPC is

The heat input to TCPC system is

The heat supply from the TCPC system to the PEMEC is

The external heat supply is expressed as

The assumptions made in the KC modeling are consistent with those for TCPC. In addition, it was assumed that the temperature and pressure of the separator remain constant; the throttling process is isenthalpic. The main design parameters of KC are shown in Table 4 [21]:

Table 4.

Main design parameters of KC circulation system.

The modeling process for the generator, turbine, condenser, pump, and regenerator in this cycle system is similar to the modeling of the TCPC. The modeling equations for the remaining components are expressed as follows [21,22,23]:

Separator:

KC mixer

KC throttling process

KC turbine l power output is

KC pump power consumption is

KC net power output system is

The external heat supply of KC system is

The following assumptions are made in PTSC modeling:

- (1)

- The solar irradiance is constant and time-invariant.

- (2)

- The efficiency of the PTSC receiver is constant.

- (3)

- The system operates in steady state condition.

The main design parameters of PTSC are shown in Table 5 [24]:

Table 5.

Main design parameters of PTSC circulation system.

The actual effective energy received by a single solar parabolic collector is expressed as [24,25]

The specific modeling formulas for each variable are detailed in the literature.

The external heat supply of the PTSC system can be expressed as

3.2. Exergy Model

The exergy is divided into physical exergy EX1 and chemical exergy EX2 [21].

Physical exergy:

Chemical exergy:

where s and s0 represent the specific entropy at the state point and the environment state, respectively kJ/(kg·K); nk represents the mole number of each component in the mixture, mol; and xk represents the molar fraction of each component in the mixture.

The system exergy balance is expressed as

where EXQ represents the system total thermal exergy, kW; Wu represents external work output, kW; I represents the system exergy loss, kW.

The thermal exergy is expressed as

where QX represents heat, kJ; TL and TH represent the temperature of low temperature and high temperature heat source, respectively, K.

3.3. Performance Evaluation Model

The TCPC system electrical efficiency is

The exergy efficiency of the TCPC system is

where Theat1, Theat2 and Tgen represents the average temperature of heat exchanger I, heat exchanger II and evaporator, respectively, K.

The electrical efficiency of the KC system is expressed as

The exergy efficiency of KC system is given by

where Tgener represents the average temperature of the generator, K.

The hydrogen production efficiency of the PEMEC system is expressed as

The PEMEC system exergy efficiency is expressed as

The IES energy efficiency is expressed as

The IES exergy efficiency is calculated by

where Theat3 represents the average temperature of heat exchanger III, K.

3.4. Model Validation

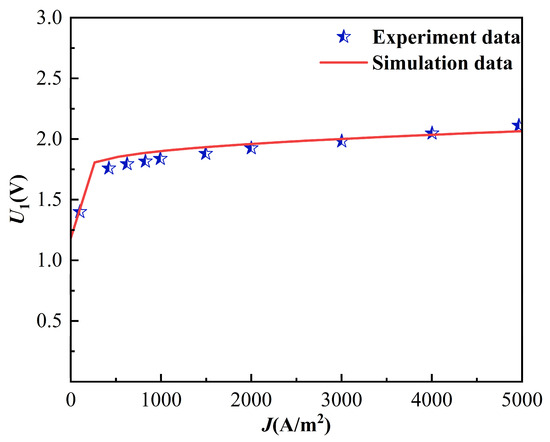

In this study, with reference to the experimental data published in the literature [26], the variation curve of the PEMEC voltage U1 with the current density Jpem was verified at an operating temperature of 353 K, ambient temperature, and ambient pressure of 293.15 K and 101.325 kPa, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, when the PEMEC current density ranges from 0 to 5000 A/m2, the trend and value of the PEMEC unit voltage changes closely with the experimental results, and the maximum calculation error of the simulation compared with the experimental data is 4.49% and the average error is 2.68%.

Figure 2.

Proton exchange membrane electrolysis cell model validation.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Simulation Results

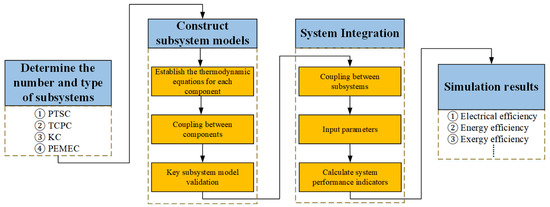

This part presents the simulation results of the proposed system and provides analysis and discussion of the effects of parameter variations on system performance. The detailed flowchart of the solution methodology employed in this study is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Detailed flowchart of the solution methodology.

The thermodynamic model was constructed by using the principle of energy cascade utilization and system integration, and the thermodynamic state points and evaluation indexes of the new IES were obtained as shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Results of each thermal state point of the IES.

Table 7.

Results of performance evaluation of the IES.

4.2. Performance Analysis

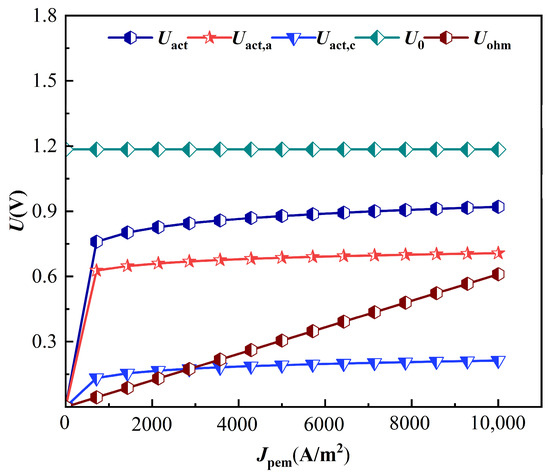

In order to better study the PEMEC operating characteristics, the polarization curve of the PEMEC was studied as shown in Figure 4. Due to the existence of various irreversible factors inside the PEMEC, polarization loss voltage and ohmic loss voltage are generated. With an increasing current density, the ohmic loss voltage shows a linear increasing trend, while the polarization loss voltage shows a rapid increasing trend followed by a slow increasing trend. The overall effect shows that the actual operating voltage of the PEMEC unit increases with the increase in current density.

Figure 4.

Proton exchange membrane electrolysis cell polarization curve.

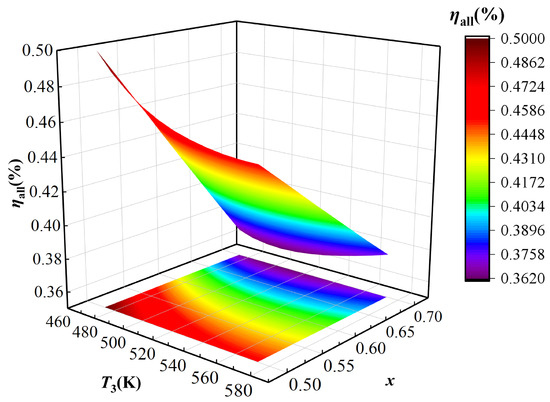

The effects of TCPC evaporator outlet temperature T3 and the basic ammonia solution concentration x of KC on the energy and the exergy efficiency of the IES are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. As shown in Figure 5, with the increase of T3, the energy efficiency of the IES continuously decreases when x is less than 0.54, and the energy efficiency of the IES first decreases and then increases when the basic ammonia solution concentration x is greater than 0.54. When T3 increases, the heat absorption of the PTSC increases, then the input heat of the IES increases; when T3 increases, the temperature of supercritical CO2 entering turbine I increases so it leads to the increase in the power generation of turbine I and TCPC, and the power output and hydrogen production of the IES increases. When x < 0.54, the increase rate of energy output from the IES is lower than the increase rate of energy input. When T3 is kept constant, the energy efficiency of the IES exhibits a consistently decreasing trend with an increasing x. This occurs because, although the power generation of the KC and the hydrogen production of the IES increase slightly, the heat load of the heat exchanger III decreases significantly. As a result, the heat supply decreases more obviously, so the energy efficiency of the IES shows a decreasing trend.

Figure 5.

Effect of parameters T3 and x on IES energy efficiency.

Figure 6.

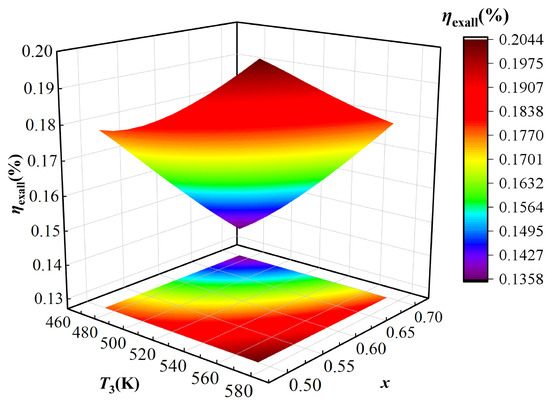

Effect of parameters T3 and x on IES exergy efficiency.

As shown in Figure 6, the IES exergy efficiency increases with the outlet temperature of the TCPC evaporator (T3), demonstrating that higher evaporator outlet temperatures strengthen the system thermodynamic performance. With an increase in T3 enhances power generation, hydrogen production, and thermal exergy supplied to the user, thereby improving overall exergy output, which consistently surpasses the IES input exergy. In addition, when the concentration of basic ammonia solution (x) increases, the IES exergy efficiency is showing a decreasing trend, which is consistent with the change trend of the IES energy efficiency. This change is attributed to the enhanced heat absorption of the KC at a higher x, which lowers the generator outlet temperature and significantly decreases the heat load of heat exchanger III, ultimately leading to a reduction in overall IES efficiency. Overall, Figure 6 highlights the crucial role of optimizing both T3 and x to maximize system exergy efficiency. Specifically, a higher T3 improves power, hydrogen, and heat cogeneration, while excessive x deteriorates system performance by weakening thermal matching in the KC subsystem. These results provide valuable guidance for selecting appropriate operating conditions in practical IES applications.

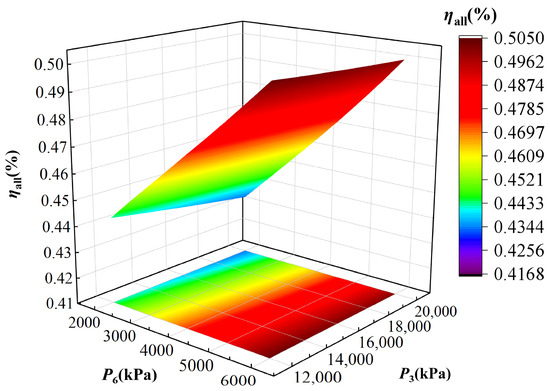

Figure 7 and Figure 8 reveal the effect of high pressure (P3) and low pressure (P6) of the TCPC on IES energy and exergy efficiency. As shown in Figure 7, the energy efficiency exhibits a slight decline when increasing high pressure P3 of the TCPC. Although higher P3 enhances power generation and hydrogen production, it simultaneously increases the condenser I cold load and decreases the heat load of heat exchanger, which makes the heat released into the low temperature heat source increase while causes the external heat supply decrease, leading to a net reduction in total energy output under constant input, thereby lowering the energy efficiency. When P3 keeps constant, the energy efficiency consistently increases when rising P6. At a higher P6, the increase in back pressure of turbine I leads to a decrease in power generation and hydrogen production. However, an elevated outlet temperature of turbine I increases the external heat supply of heat exchanger II, and this gain outweighs the losses in power generation and hydrogen production, resulting in an overall improvement in system efficiency. Overall, although an increasing P3 favors power generation, it compromises energy efficiency by reducing heat recovery. These conclusions are valuable for identifying optimal pressure ranges in the practical IES operation, balancing cogeneration performance, and system efficiency.

Figure 7.

Effect of parameters P3 and P6 on energy efficiency of IES.

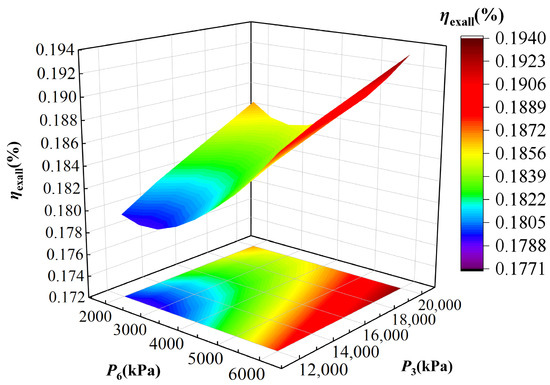

Figure 8.

Effect of parameters P3 and P6 on exergy efficiency of IES.

As shown in Figure 8, the exergy efficiency of the IES exhibits a slight upward trend with increasing P3, in contrast to the decreasing trend observed for energy efficiency. The reason is that although a higher P3 reduces the heat load of heat exchanger II, it simultaneously increases its average temperature, thereby yielding a gradual improvement in overall exergy efficiency. As P6 increases, the exergy efficiency of the IES first decreases and then increases, reaching a minimum at P6 of 2500 kPa. When P6 is less than 2500 kPa, the lower outlet temperature of turbine I reduces the thermal exergy output of heat exchanger II, while the output power and hydrogen production also decline, leading to a downward trend in exergy efficiency. When P6 is greater than 2500 kPa, the rising outlet temperature of turbine I enhances the thermal exergy output of heat exchanger II at a rate that outweighs the reductions in power and hydrogen production, resulting in an increase in exergy efficiency. Overall, while increasing P3 improves thermodynamic quality of heat utilization, the nonlinear response of exergy efficiency to P6 indicates the existence of a worst operating condition around 2500 kPa. These findings could provide practical guidance for tuning TCPC pressures to balance energy and exergy performance in IES operation.

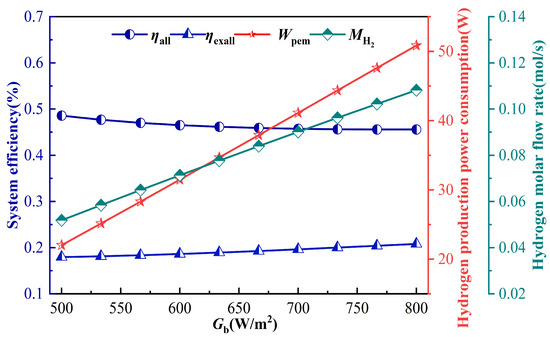

Figure 9 shows the effect of solar irradiance Gb on the IES performance, when Gb increases, the PTSC absorbs more heat, thereby increasing the total input energy. This elevates the solar collector outlet temperature and enthalpy, which in turn enhances system power generation and increases the power supplied to the PEMEC. Then the current density of PEMEC increases, which makes the increase of hydrogen production. Since an increase in Gb leads to an increase in T3, the trend of the energy and exergy efficiency are consistent with the trend of the IES efficiency with T3 shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Overall, Figure 9 highlights the dual effect of solar irradiance: while a greater irradiance improves system output in terms of power and hydrogen production, it simultaneously lowers the energy efficiency. These findings underscore the importance of matching solar resource variability with electrolyzer operating conditions to achieve balanced system performance in practical applications.

Figure 9.

Effect of parameter Gb on IES.

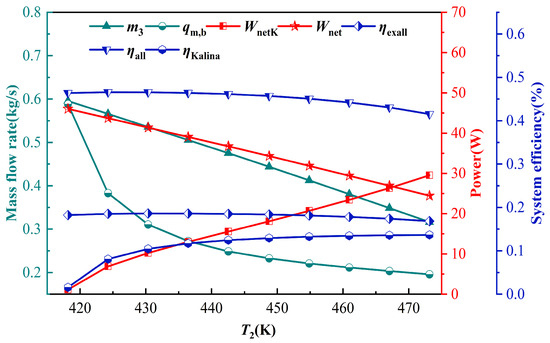

Figure 10 shows the effect of the TCPC evaporator outlet temperature T2 (KC generator inlet) on the IES performance. As T2 increases, the heat absorption of the TCPC evaporator decreases, leading to a reduction in the mass flow rate, and the net external power output of the TCPC decreases, all other conditions being constant. When T2 increases, the heat absorption of the KC generator increases, the enthalpy difference in the ammonia-water solution across the generator increases, causing the mass flow rate of the KC to decrease, but the temperature of the ammonia rich vapor increases, making the net power of the external output of the KC increase and the electrical efficiency of the KC system rise higher. As shown in Figure 10, with an increasing T2, the power generation of the TCPC gradually decreases, while that of the KC gradually increases. Since the power output of the TCPC is larger than KC system, the energy efficiency and the exergy efficiency of the IES show a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, and when T2 = 430.35 K, the energy efficiency and the exergy efficiency of the IES reach the maximum value of 46.52% and 18.62%, respectively, and while it is figured up that the hydrogen production flow rate is of the IES is 0.5136 kg/h.

Figure 10.

Effect of parameter T2 on IES.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel solar driven IES for hydrogen production and cogeneration based on renewable energy generation and hydrogen production and energy cascade utilization. The thermodynamic analysis is carried out, and the analysis of the key parameters is conducted. The following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- Under design conditions, the PEMEC achieves a hydrogen production output of 15.98 kW with a corresponding hydrogen flow rate of 0.5136 kg/h, while attaining a hydrogen production efficiency of 54.09% and an exergy efficiency of 51.59%. The electrical efficiency of the TCPC and the KC are 15.54% and 11.11%, and the exergy efficiency are 49.72% and 38.33%, respectively. The total energy and exergy efficiencies reach 46.52% and 18.62%, respectively.

- (2)

- The system performance is highly sensitive to operating parameters. Higher TCPC outlet temperature (T3) and working fluid concentration (x) significantly affect energy and exergy efficiencies, with nonlinear trends depending on the concentration range.

- (3)

- The TCPC pressure variations exhibit opposite effects on energy and exergy efficiencies, indicating a trade-off between power/hydrogen output and thermal utilization, with an optimal region near P6 = 2500 kPa.

- (4)

- Solar irradiance (Gb) directly enhances power and hydrogen outputs, but the efficiency trends are similar to those induced by temperature changes.

- (5)

- The optimal system performance is obtained when the TCPC evaporator outlet temperature (T2) is 430.35 K, at which the IES attains the maximum energy efficiency and the exergy efficiency of 46.52% and 18.62%, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z.; methodology, Q.Z.; software, Q.Z. and H.L.; data Curation, Q.Z. and H.L.; validation, H.L. and H.Z.; writing—original draft, H.L. and Z.Y.; review and editing, H.Z. and Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Technology Projects of Nari Technology Co, Ltd., China (Research on key technologies for low carbon friendly interaction between hydrogen energy and power grid, grant number 524606210036).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qing Zhu, Huijie Lin and Hongjuan Zheng were employed by Nari Technology Co., Ltd. and NARI Group Corporation. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, H.M.; Wang, J.Z.; Li, R.R.; Lu, H.Y. Novel analysis–forecast system based on multi-objective optimization for air quality index. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 208, 1365–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Zhang, L.F.; Niu, X.S.; Liu, Z.K. Effects of PM2.5 on health and economic loss: Evidence from Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Jimenez, J.J.; Tzianoumis, A.L.; Yang, Q.; Livina, V.N. Long-term wind and solar energy generation forecasts, and optimisation of Power Purchase Agreements. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.M. A fuzzy intelligent forecasting system based on combined fuzzification strategy and improved optimization algorithm for renewable energy power generation. Appl. Energy 2022, 325, 119849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, F.Y.; Chen, C.N.; Zhao, H.R.; Yu, Z.T. Performance assessment of hydrogen-cooling-heating-electricity integrated energy system driven by solar energy. Dist. Ut. 2022, 39, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Smolinka, T.; Bergmann, H.; Garche, J.; Kusnezoff, M. Chapter 4—The history of water electrolysis from its beginnings to the present. In Electrochemical Power Sources: Fundamentals, Systems, and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 83–164. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.H.; Lin, J.G.; Zhang, X.; Luo, H.H.; Hou, Y. Investigation on the Application of Carbon Dioxide Power Generation Cycles in Solar Energy Heating Utilization. Power Syst. Eng. 2020, 36, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Meftahpour, H.; Saray, R.K.; Aghaei, A.T.; Bahlouli, K. Comprehensive analysis of energy, exergy, economic, and environmental aspects in implementing the Kalina cycle for waste heat recovery from a gas turbine cycle coupled with a steam generator. Energy 2024, 290, 130094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.T.; Su, R.Z.; Feng, C.Y. Thermodynamic analysis and multi-objective optimization of a novel power generation system driven by geothermal energy. Energy 2020, 199, 117381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Khan, F.; Zhang, Y.H.; Djire, A. Recent development in electrocatalysts for hydrogen production through water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 32284–32317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, A.; Hakkaki-Fard, A. Thermodynamic analysis of a photovoltaic thermal system coupled with an organic Rankine cycle and a proton exchange membrane electrolysis cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 17894–17913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafchi, F.M.; Baniasadi, E.; Afshari, E.; Javani, N. Performance assessment of a solar hydrogen and electricity production plant using high temperature PEM electrolyzer and energy storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 5820–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Madheswaran, D.K.; Kannan, A.M.; Sureshvaran, U.; Sathish, J. Can hydrogen be the sustainable fuel for mobility in India in the global context? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 33571–33596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, E. Seasonal Storage of Thermal Energy-Swedish Experience. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 1988, 110, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.W.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Shu, S.M.; Tu, Z.K.; Chan, S.H.; Chen, R.; Wang, X.D. Energy- and exergy-based working fluid selection and performance analysis of a high-temperature PEMFC-based micro combined cooling heating and power system. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Duan, L.Q.; Wang, X.M.; Lu, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.F. Thermodynamic performance analysis of a novel PEMEC-SOFC-based poly-generation system integrated mechanical compression and thermal energy storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 265, 115770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, X.H.; Zeng, Q.H.; Deng, H.L.; Gao, X.Y.; Xu, H.L. Research on heat and mass transfer of PEMEC anode flow channel based on topology optimization. Fuel 2026, 404, 136144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valverde, R.; Espinosa, N.; Urbina, A. Simple PEM water electrolyser model and experimental validation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 1927–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Mo, J.K.; Kang, Z.Y.; Yang, G.Q.; Barnhill, W.; Zhang, F.Y. Modeling of two-phase transport in proton exchange membrane electrolyzer cells for hydrogen energy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 4478–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.X.; Yu, Z.T.; Bai, S.Z.; Li, G.X.; Wang, D.H. Study on a near-zero emission SOFC-based multi-generation system combined with organic Rankine cycle and transcritical CO2 cycle for LNG cold energy recovery. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 253, 115188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, F.; Ozveren, U. Energy and exergy analysis of entrained bed gasifier/GT/Kalina cycle model for CO2 co-gasification of waste tyre and biochar. Fuel 2022, 331, 125943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazazmeh, A.J.; Khaliq, A.; Shivlal. Energetic and exergetic investigation on a solar powered integrated system of ejector refrigeration cycle and Kalina cycle. Int. J. Exergy 2022, 39, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, Z.A.; Chen, H.F.; Liu, X.Q. Thermodynamic Analysis of a New Combined Cooling and Power System Coupled by the Kalina Cycle and Ammonia–Water Absorption Refrigeration Cycle. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlu, S.; Dincer, I. Development and analysis of a solar and wind energy based multigeneration system. Sol. Energy 2015, 122, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghghi, M.A.; Pesteei, S.M.; Chitsaz, A.; Hosseinpour, J. Thermodynamic investigation of a new combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) system driven by parabolic trough solar collectors (PTSCs): A case study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 163, 114329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioroi, T.; Yasuda, K.; Siroma, Z.; Fujiwara, N.; Miyazaki, Y. Thin film electrocatalyst layer for unitized regenerative polymer electrolyte fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2002, 112, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).