Abstract

Mercury (Hg) contamination in water and soil poses severe ecological and human health risks, yet conventional sorbents often suffer from limited capacity, selectivity, and stability. Here, we report a bifunctional porous organic polymer (AMTD-TCT) rationally constructed by covalently crosslinking 2-amino-5-mercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole with trichlorotriazine, thereby integrating abundant sulfur and nitrogen coordination sites within a stable mesoporous framework. AMTD-TCT exhibits an ultrahigh Hg(II) adsorption capacity of 1257.7 mg g−1, far exceeding most reported porous sorbents. Adsorption follows monolayer chemisorption, governed by strong S–Hg and N–Hg coordination and Na+/Hg2+ ion exchange, while hierarchical porosity ensures rapid diffusion and efficient utilization of active sites. The polymer maintains robust performance over a wide pH range and demonstrates strong retention with minimal desorption, underscoring its environmental durability. These findings highlight AMTD-TCT as a highly effective and scalable platform for Hg(II) remediation in complex aqueous–soil systems and illustrate a generalizable molecular design strategy for developing multifunctional porous polymers in advanced separation and purification technologies.

1. Introduction

Mercury (Hg) is a globally persistent and highly toxic heavy metal that poses serious environmental and public health risks due to its strong bioaccumulation potential, long-term environmental stability, and high mobility across terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [1,2]. Among its various chemical forms, divalent mercury (Hg(II)) predominates under natural conditions and readily participates in soil–water geochemical cycling, facilitating its entry into food chains and causing irreversible ecological damage and human exposure [3]. Extensive epidemiological and toxicological studies have linked Hg exposure to severe health disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease), hepatic and renal dysfunction, immune suppression, and developmental impairments in children even at low chronic exposure levels [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), anthropogenic activities release more than 2000 tons of Hg annually, over 60% of which is retained in soils and sediments. As a result, approximately 12.1% of agricultural soils globally exceed recommended Hg safety thresholds, and frequent Hg contamination incidents are reported in surface waters, especially in regions influenced by industrial discharges and legacy mining activities.

To mitigate the environmental and health risks associated with Hg contamination, adsorption-based remediation has emerged as one of the most effective in situ strategies for Hg(II) removal from contaminated soils and aqueous environments, owing to its operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and environmental compatibility [11,12,13]. However, conventional sorbents, such as activated carbon and ion exchange resins, often exhibit inherently low Hg(II) adsorption capacities (typically <200 mg g−1), along with poor selectivity and limited chemical stability in complex environmental matrices [11,14]. In recent years, advanced porous materials, notably metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs), have demonstrated significantly enhanced Hg(II) uptake performance. Nonetheless, their large-scale application remains limited due to critical drawbacks. For instance, MOFs often suffer from hydrolytic instability under aqueous conditions (e.g., ligand dissociation), while COFs typically require elaborate and time-consuming synthesis protocols, including precise crystallization control. Furthermore, both MOFs and COFs commonly rely on expensive metal-based catalysts or monomers, limiting their scalability and economic feasibility [15,16,17,18]. Therefore, there remains an urgent need to develop next-generation adsorbents that integrate ultrahigh Hg(II) capacity, structural tunability, environmental resilience, and scalable synthesis into a unified platform.

Over the past decade, porous organic polymers (POPs) have gained increasing attention as emerging adsorbents for heavy-metal remediation owing to their structural versatility, chemical robustness, and high design flexibility. POPs are lightweight, three-dimensional networks of covalently linked organic building blocks, and are particularly attractive for environmental applications due to their tunable functionality, high surface area, and hierarchical porosity [19,20,21,22,23]. Among them, POPs functionalized with nitrogen and sulfur donor atoms have shown particular efficacy for Hg(II) capture, primarily through the formation of strong S-Hg covalent bonds and N-Hg coordination interactions [24,25,26,27]. Nevertheless, most reported N/S-rich POPs still suffer from a relatively low density of accessible binding sites, and limited mass-transfer rates, which can severely compromise performance under environmentally relevant conditions. Moreover, variable solution pH, ionic strength, and the presence of humic substances in soil leachates can further attenuate adsorption capacity and selectivity by altering functional-group protonation states and competitive sorption equilibria.

In this study, we propose a rational, functionality-guided molecular design strategy to construct a novel porous organic polymer (designated as AMTD-TCT), featuring dual nitrogen/sulfur coordination sites tailored for Hg(II) immobilization. Specifically, 2-amino-5-mercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole (AMTD) is covalently crosslinked with trichlorotriazine (TCT) through nucleophilic aromatic substitution, resulting in a chemically stable polymeric network enriched with thiol and triazine nitrogen ligands. This bifunctional design simultaneously maximizes binding-site density and ensures a hierarchically mesoporous structure to alleviate diffusion resistance under complex soil–water conditions. First, it integrates two distinct coordination motifs, the thiol (-SH) groups from the thiadiazole moieties and nitrogen atoms from the triazine rings, which provide highly selective and high-affinity binding sites for Hg(II), enabling efficient complexation. Second, it features a hierarchically mesoporous architecture, which significantly reduces diffusion resistance and promotes rapid ion transport. Third, the fully organic, metal-free backbone offers excellent physicochemical stability over a broad pH range, effectively addressing the dissolution issues that commonly affect inorganic or metal-based adsorbents. Microscopic and spectroscopic analyses confirm that Hg(II) uptake is predominantly governed by strong chemical coordination at the N/S functional groups [28,29]. This work represents the demonstration of a dual N/S-coordinated POP engineered specifically for aqueous-soil Hg(II) sequestration, achieving ultrahigh capacity and fast kinetics under competitive conditions.

This study primarily focuses on the rational design, synthesis, and fundamental characterization of AMTD-TCT, along with a systematic evaluation of its Hg(II) adsorption performance through well-controlled batch experiments. The scope includes investigating key parameters such as solution pH, initial concentration, contact time, and adsorbent dosage, as well as elucidating the adsorption mechanisms through comprehensive spectroscopic analyses. However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of the present work: (1) the adsorption experiments were conducted under standardized laboratory conditions (25 °C) and the effect of temperature was not systematically investigated; (2) the study employed batch systems rather than continuous-flow configurations; (3) the performance was evaluated in simulated Hg(II) solutions rather than complex real wastewater matrices containing multiple competing ions and organic matter; and (4) long-term stability and regeneration studies under field conditions were beyond the scope of this initial investigation. These aspects represent important directions for future research to fully assess the practical potential of AMTD-TCT. Taken together, this work presents a versatile and scalable POP platform for Hg(II) capture, offering a generalizable strategy for the development of next-generation heavy-metal adsorbents with superior selectivity, robustness, and environmental applicability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of AMTD-TCT

First, 1.08 mmol of TCT (GR grade, Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was accurately weighed and dissolved in 10 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF; GR grade, Tianjin Funing Fine Chemical Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) at room temperature. The solution was sonicated using an ultrasonic cleaner (SG8200H, Shanghai Guante Ultrasonic Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for 5 min to ensure homogeneity, resulting in a clear TCT solution. Similarly, 3.24 mmol of AMTD (HPLC grade, Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was dissolved in 10 mL of DMF under the same conditions to obtain a homogeneous AMTD solution.

Under continuous mechanical stirring (160 rpm, DNP-4L, Hunan Beckman Holdings Co., Ltd., Changde, China), the TCT solution was added dropwise to the AMTD solution. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 8 h. Subsequently, the pH of the reaction mixture was slowly adjusted using a 2 mol L−1 sodium hydroxide solution (NaOH; GR grade, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), while monitoring the pH with a pH meter (PHS-3C, Shanghai INESA Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The reaction was terminated when the pH reached 12.

The resulting product was washed with absolute ethanol (EtOH; GR grade, Tianjin Funing Fine Chemical Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), separated by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 5 min) using a centrifuge (H1850, Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., Xiangtan, China), and dried in a vacuum oven (DZ-2A II, Tianjin Test Instrument Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) at 60 °C for 12 h. A pale yellow solid powder was obtained and designated as AMTD-TCT (Figure S1c). The synthesis process was conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere to minimize oxidation of thiol groups.

2.2. Adsorption–Desorption Experiments

In this study, three different adsorbents were used: synthesized AMTD-TCT, soil (collected from a farmland in Huaxi District, Guiyang City, Guizhou Province, China; 106.63° E, 26.38° N), and a 1:1 (w/w) mixture of AMTD-TCT and soil. Hg(II) ions were used as the adsorbate to investigate the adsorption and desorption behavior of each adsorbent. According to the experimental design (Table S1), a 2000 mL solution of 300.00 mg L−1 mercuric nitrate (Hg(NO3)2; GR grade, Shandong Xiya Chemical Co., Ltd., Lingyi, China) was prepared. The initial Hg(II) concentration range of 50–300 mg L−1 was selected for the isotherm studies primarily to adequately characterize the maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) of the adsorbents and to facilitate direct comparison with the performance of other reported sorbents, which are often evaluated under similar high-concentration conditions for benchmarking purposes [30,31]. This concentration range is not arbitrary but aligns with the actual Hg levels in specific industrial Hg-laden wastewaters: for example, leachates from mercury mine wastes in the Big Bend region, Texas, USA, have been reported to contain Hg concentrations as high as 760 µg of Hg per gram of leached sample. When calculated based on a common liquid-solid ratio (1:1, widely used in lab leaching tests for mine wastes), this translates to an aqueous Hg concentration of 760 mg L−1, far exceeding the upper limit of the 50–300 mg L−1 range selected in this study, confirming the practical relevance of targeting high Hg concentrations for industrial wastewater remediation [31]. Additionally, while chlor-alkali electrolysis wastewater (a typical industrial Hg-containing stream) has a relatively lower Hg concentration range of 3–10 mg L−1, it represents a precursor to more concentrated Hg waste streams (e.g., after evaporation or pre-concentration in treatment processes), further justifying the selection of 50–300 mg L−1 to cover potential high-concentration scenarios [30].

It is acknowledged that Hg concentrations in most natural waters and many waste streams are typically several orders of magnitude lower (e.g., µg L−1 to low mg L−1 range). For instance, the median concentration of total Hg (THg) in ambient river samples adjacent to power plants is only 2.3 ng L−1, and even in power plant wastewater (a point source), the median THg is 7.1 ng L−1, both far below the 50 mg L−1 threshold [32]. These data collectively confirm that natural waters and non-industrial waste streams have minimal Hg concentrations, in stark contrast to the high levels observed in specific industrial wastewaters. Future studies will focus on evaluating the adsorption performance and selectivity of AMTD-TCT at these environmentally relevant concentrations.

The pH of the Hg(II) solution was then adjusted to 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 using 0.1 mol L−1 sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl; GR grade, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Subsequently, 20 mL of the pH-adjusted Hg(II) solution and 3 mg of adsorbent (0.15 g L−1) (Soil, AMTD-TCT, or AMTD-TCT + Soil) were added to centrifuge tubes assigned to different treatments. The tubes were shaken in a thermostatic oscillator (SHZ-82, Changzhou Aohua Instrument Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China) maintained at 25 °C for 120 min. Afterward, the suspensions were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. The concentration of Hg(II) in the supernatant was measured to analyze the adsorption characteristics and influencing factors for each adsorbent.

A blank control (CK), consisting of 20 mL of Hg(II) solution without any adsorbent, was included to assess the potential adsorption of Hg(II) onto the inner wall of the centrifuge tube and to exclude the influence of non-target factors. Additionally, a control group with Hg(II) solution alone was used to demonstrate that the adsorption of Hg(II) by the centrifuge tube was negligible and that the majority of Hg(II) removal could be attributed to the adsorbents.

After equilibrium was reached for all treatments, the supernatant was removed, and 20.00 mL of 0.01 mol L−1 sodium nitrate (NaNO3; GR grade, Tianjin Comeo Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) solution was added to each tube. The NaNO3 solution served as a low-ionic-strength background electrolyte to simulate mild leaching conditions, allowing evaluation of the retention stability and potential remobilization risk of the adsorbed Hg(II). The mixtures were shaken at 25 °C for another 120 min and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. The Hg(II) concentration in the supernatant was then measured to evaluate the desorption behavior of each adsorbent. All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. All batch adsorption experiments were performed at 25 °C to establish consistent baseline performance data under controlled laboratory conditions, simulating common ambient temperature scenarios. This standardized approach enables direct comparison with other adsorbent materials typically reported under similar conditions [33,34].

2.3. Measurements

The concentration of Hg2+ in the supernatant was determined according to US EPA Method 1631, using the stannous chloride (SnCl2, GR, Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., China) reduction-cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometry method (Model III, Brooks Rand, USA) [35,36]. To verify the successful synthesis of AMTD-TCT and to investigate the microscopic binding characteristics between AMTD-TCT and Hg2+, the functional groups of AMTD, TCT, AMTD-TCT, and AMTD-TCT after Hg2+ adsorption (AMTD-TCT+Hg) were characterized using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS20, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Elemental compositions and chemical states of AMTD, AMTD-TCT, and AMTD-TCT+Hg were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific Nexsa, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The microstructures of AMTD-TCT and AMTD-TCT+Hg were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Scios 2 HiVac, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA), and the pore structure of AMTD-TCT was characterized using a fully automated specific surface area and porosity analyzer (BET, Micromeritics ASAP 2460, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA).

2.4. Data Analysis

The adsorption capacity, removal efficiency, and desorption rate of Hg2+ by the adsorbents were calculated using Equations (1)–(3), respectively [37]:

where qe is the adsorption capacity of Hg2+ by the adsorbent (mg L−1), c0 and ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of Hg2+ in solution (mg L−1), respectively. v is the volume of the solution (L), m is the mass of the adsorbent (g), γ is the removal efficiency (%), η is the desorption rate (%), and ca is the concentration of desorbed Hg (mg L−1).

The isothermal adsorption characteristics of the three types of adsorbents were fitted using the Langmuir (Equation (4)) and Freundlich (Equation (5)) isotherm models [38,39,40,41].

where qe is the amount of Hg2+ adsorbed at equilibrium (mg g−1), ce is the equilibrium concentration of Hg2+ in solution (mg L−1), qm is the theoretical maximum adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg g−1), KL is the Langmuir constant, KF and n are the empirical constants of the Freundlich model.

To further investigate the adsorption mechanism and characterize the porosity-related adsorption behavior, the Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm model (Equation (6)) was employed [42,43]:

where ε is the Polanyi potential calculated as ε = RTln(1 + 1/Ce), qm (mg g−1) is the theoretical saturation capacity, β (mol2 kJ−2) is the D-R constant related to the mean free energy of adsorption, R (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) is the ideal gas constant, and T (K) is the absolute temperature. The mean free energy of adsorption E (kJ mol−1) can be calculated from the β value using E = 1/√(2β).

The adsorption kinetics were fitted using the pseudo-first-order (Equation (7)) and pseudo-second-order (Equation (8)) kinetic models [44]:

where qe is the adsorption capacity of Hg2+ by the adsorbent at equilibrium (mg g−1), qt is the adsorption capacity at time t (mg g−1), k1 and k2 are the rate constants of the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models, respectively (min−1 and g mg−1 min−1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Characterization of AMTD-TCT

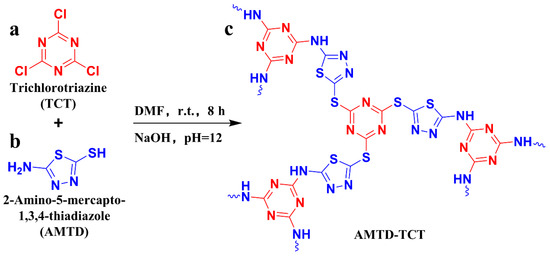

TCT is an aromatic compound containing a triazine ring (C3N3Cl3), in which each of the three carbon atoms in the ring is bonded to a chlorine atom via C-Cl bonds (Figure 1a). Chlorine (Cl), the signature element of TCT, plays a crucial role in its reactivity. Due to its high electronegativity, these C-Cl bonds are prone to nucleophilic substitution, making them ideal reactive sites for constructing covalent organic frameworks [45]. AMTD contains amino (-NH2) and thiol (-SH) functional groups, which are polar and include the heteroatoms sulfur (S) and nitrogen (N) in its structure (Figure 1b). As nucleophilic centers, S and N atoms in AMTD can readily attack the electrophilic C-Cl bonds in TCT, forming stable covalent C-S and C-N bonds through nucleophilic substitution reactions [46,47]. The presence of these characteristic elements (Cl in TCT, S and N in AMTD) and their respective functional groups forms the essential chemical basis for the reaction between AMTD and TCT, ultimately leading to the successful synthesis of the AMTD-TCT compound.

Figure 1.

Reaction scheme between TCT and AMTD: (a) molecular structure of TCT; (b) molecular structure of AMTD; (c) molecular structure of AMTD-TCT.

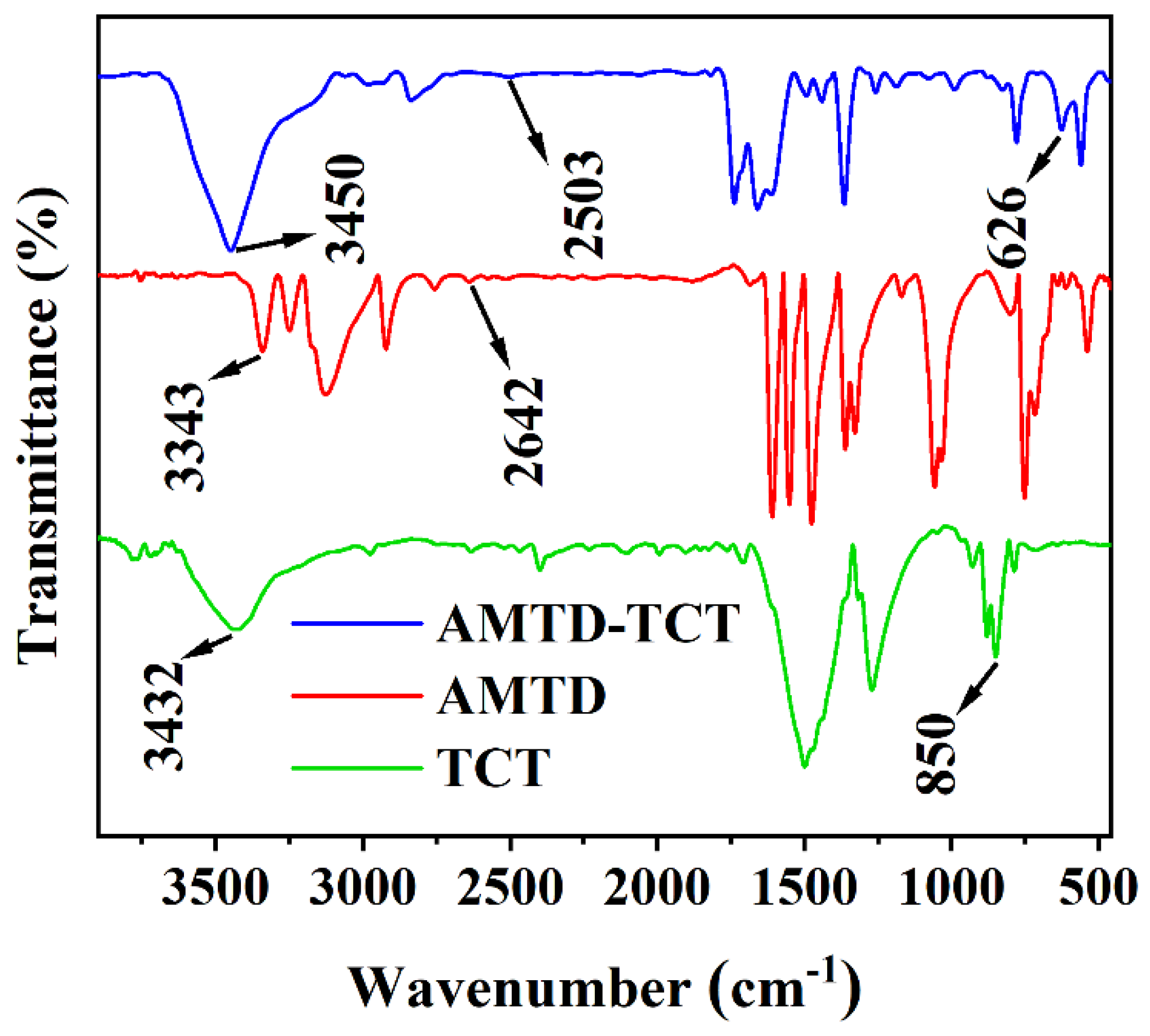

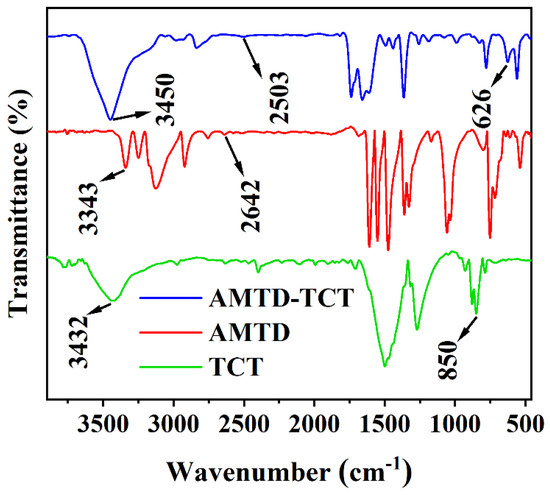

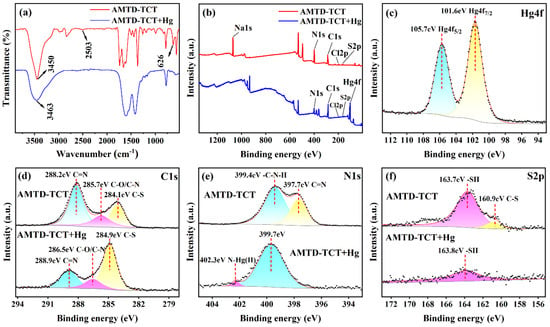

FTIR characterization (Figure 2, the unprocessed FTIR spectra for all materials are provided in Figure S1 of the Supporting Information.) revealed several key structural features of the materials. A characteristic stretching vibration peak of the C-Cl bond in TCT was observed at 850 cm−1, while the broad absorption band at 3432 cm−1 is attributed to partial hydrolysis of TCT during synthesis [48,49,50]. In the spectrum of AMTD, the peaks at 2642 cm−1 and 3343 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of the -SH and -NH2 groups, respectively [51]. In AMTD-TCT, the -SH stretching peak redshifts from 2642 to 2503 cm−1 (a redshift), indicating that some thiol groups of AMTD reacted with the triazine ring to form covalent C-S bonds. This shift is due to changes in the electron cloud density of sulfur atoms upon covalent bond formation, altering the vibrational dipole moment and reducing the stretching frequency.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of AMTD, TCT, and AMTD-TCT.

Additionally, the characteristic C-Cl peak at 850 cm−1 was no longer observed in AMTD-TCT, and a new C-S characteristic peak appeared at 626 cm−1 [52,53]. These changes confirm that the C-Cl groups in TCT were substituted by AMTD through nucleophilic substitution. Furthermore, the broad band at 3450 cm−1 in the AMTD-TCT spectrum is a composite signal arising from the -NH (3350–3300 cm−1) and -NH2 (3400–3350 cm−1) groups in AMTD, along with -OH groups (3450–3400 cm−1) formed via partial hydrolysis of TCT [54].

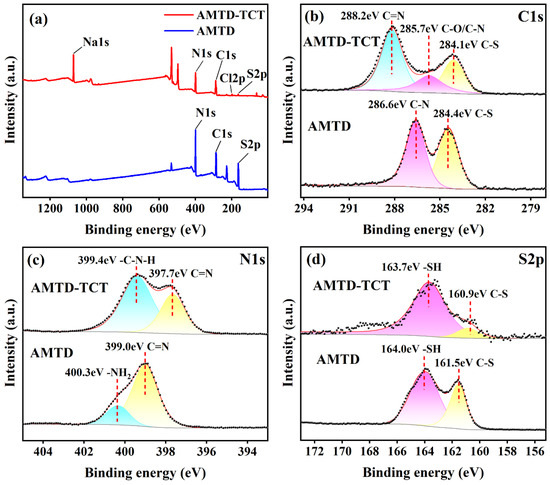

XPS analysis provided additional confirmation of successful synthesis and elemental incorporation (Figure 3). In the survey spectrum of AMTD-TCT (Figure 3a), the appearance of chlorine, absent in pristine AMTD, validates the integration of TCT. High-resolution C 1s spectra of AMTD (Figure 3b) show peaks at 284.4 eV (C-S) and 286.6 eV (C-N) [55,56], while the N 1s spectrum contains peaks at 399.0 eV and 400.3 eV, corresponding to C=N and -NH2 groups (Figure 3c) [54]. The S 2p spectrum of AMTD shows peaks at 161.5 eV (C-S) and 164.0 eV (-SH) [57] (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

XPS spectra of AMTD and AMTD-TCT: (a) survey spectrum; (b) high-resolution C 1s spectrum; (c) high-resolution N 1s spectrum; (d) high-resolution S 2p spectrum.

After polymerization, a new C 1s peak appears at 288.2 eV in AMTD-TCT (Figure 3b) consistent with the C=N bonds of triazine rings from TCT [56]. Simultaneously, binding energy shifts in C-N, C-S, and N 1s regions indicate changes in the electronic environment, suggesting formation of new covalent bonds. The weakening or disappearance of the -SH and C-S signals, coupled with the new Cl and triazine signatures, strongly support the formation of a covalently crosslinked polymer via C-N and C-S linkages. Minor shifts in the S 2p and N 1s peaks of AMTD-TCT also indicate decreased electron density, likely due to electron delocalization in the polymeric backbone.

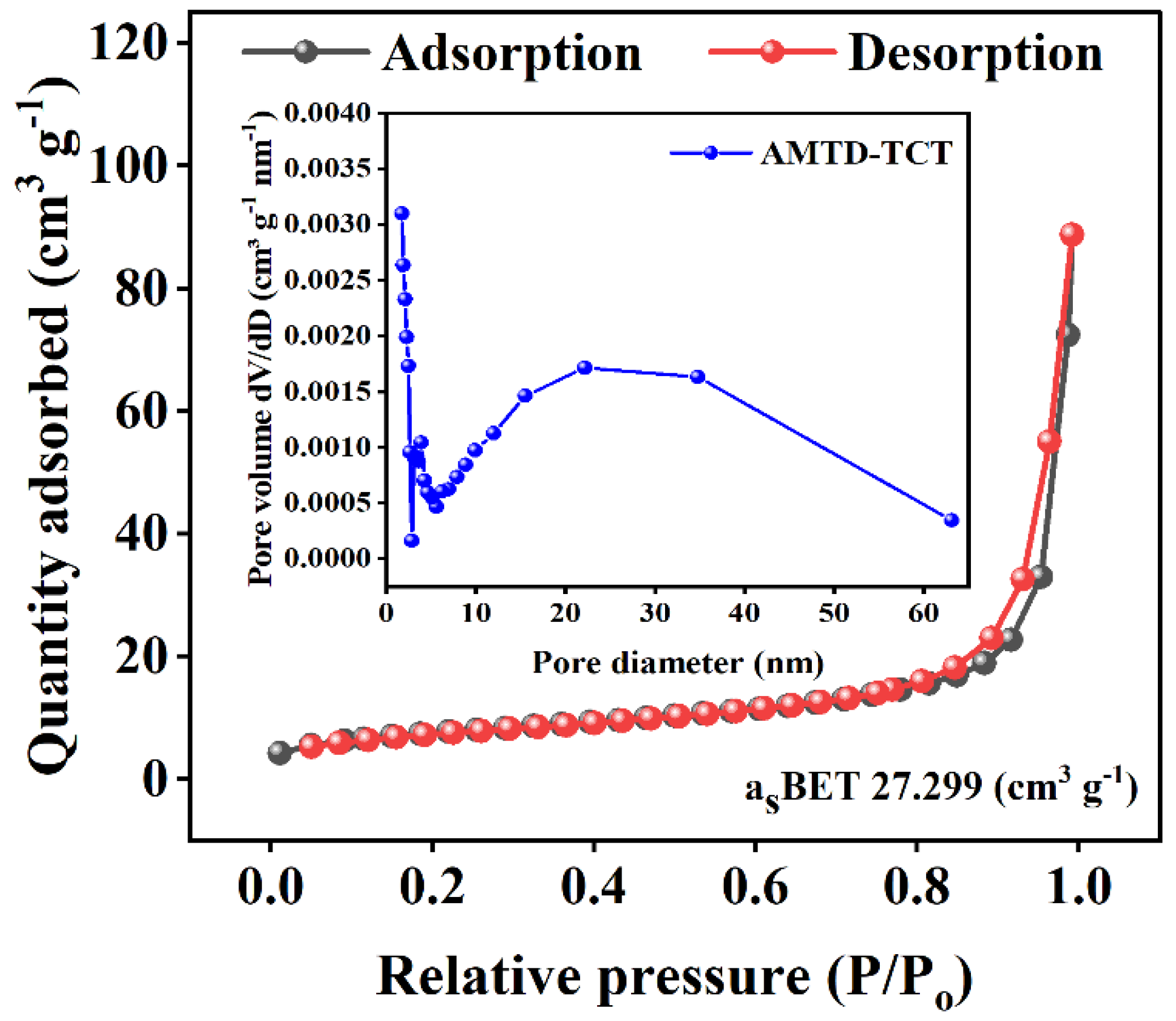

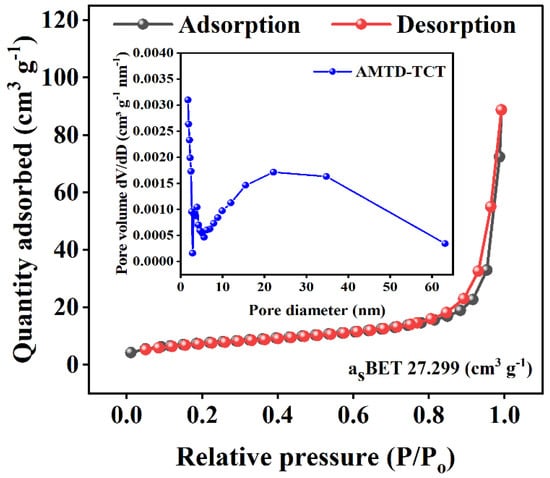

The porosity and surface characteristics of AMTD-TCT were assessed using nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms (Figure 4). The isotherm profile corresponds to a type IV hysteresis loop, indicative of mesoporous structures [58]. The BET surface area was determined to be 27.30 m2 g−1, with an average pore diameter of approximately 24.45 nm. The Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size distribution ranged from 1.74 to 22.71 nm, confirming the coexistence of micropores and mesopores, with mesoporosity predominating [59].

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and pore size distribution of AMTD-TCT.

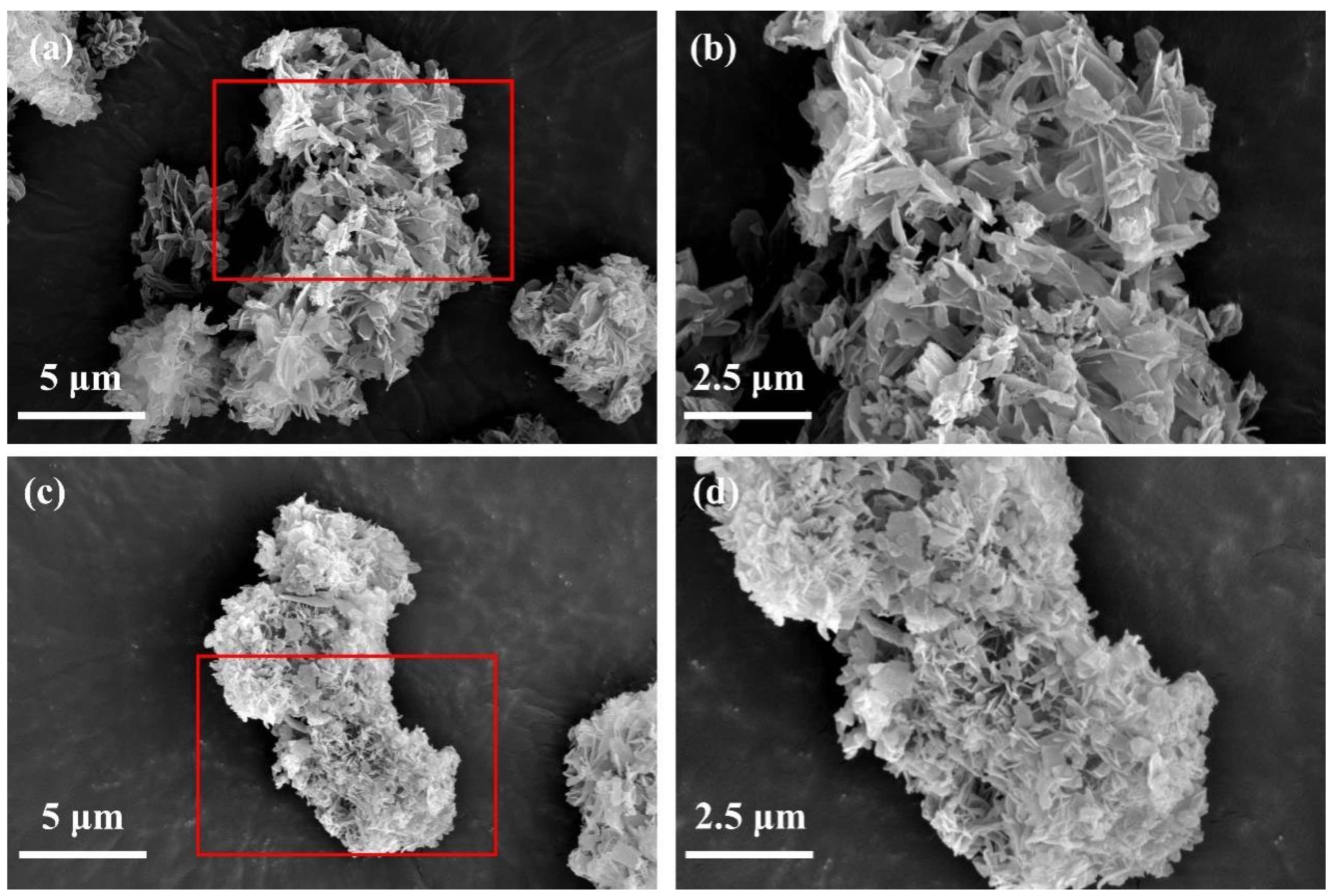

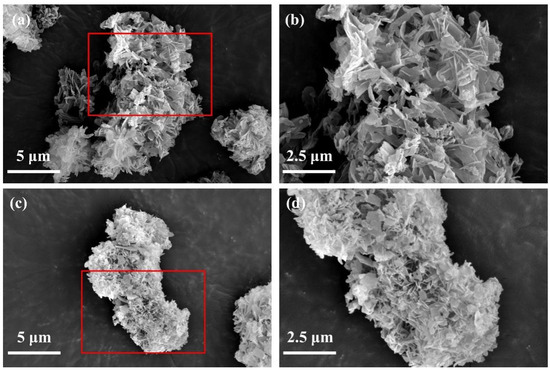

SEM images (Figure 5) confirm that AMTD-TCT exhibits an irregularly stacked morphology composed of primary particles predominantly in the micrometer scale (approximately 1–20 μm), forming flake-like layers and a rough, porous surface. This architecture, combined with the high surface area revealed by BET analysis, is consistent with the multiscale pore features of POPs [19,23]. The hierarchical porosity facilitates mass transport of Hg(II) ions, while the abundance of exposed N/S donor sites enhances surface reactivity. Together, these features endow AMTD-TCT with structural and functional properties ideal for high-efficiency heavy metal ion adsorption in batch systems.

Figure 5.

SEM images of AMTD-TCT: (a) Low-magnification overview image; (b) Higher-magnification image of the area indicated by the red square in (a); (c) Low-magnification image showing a different region; (d) Higher-magnification image of the area indicated by the red square in (c).

3.2. Influence Factors of Hg(II) on AMTD-TCT in Soil-Water System

Effects of pH

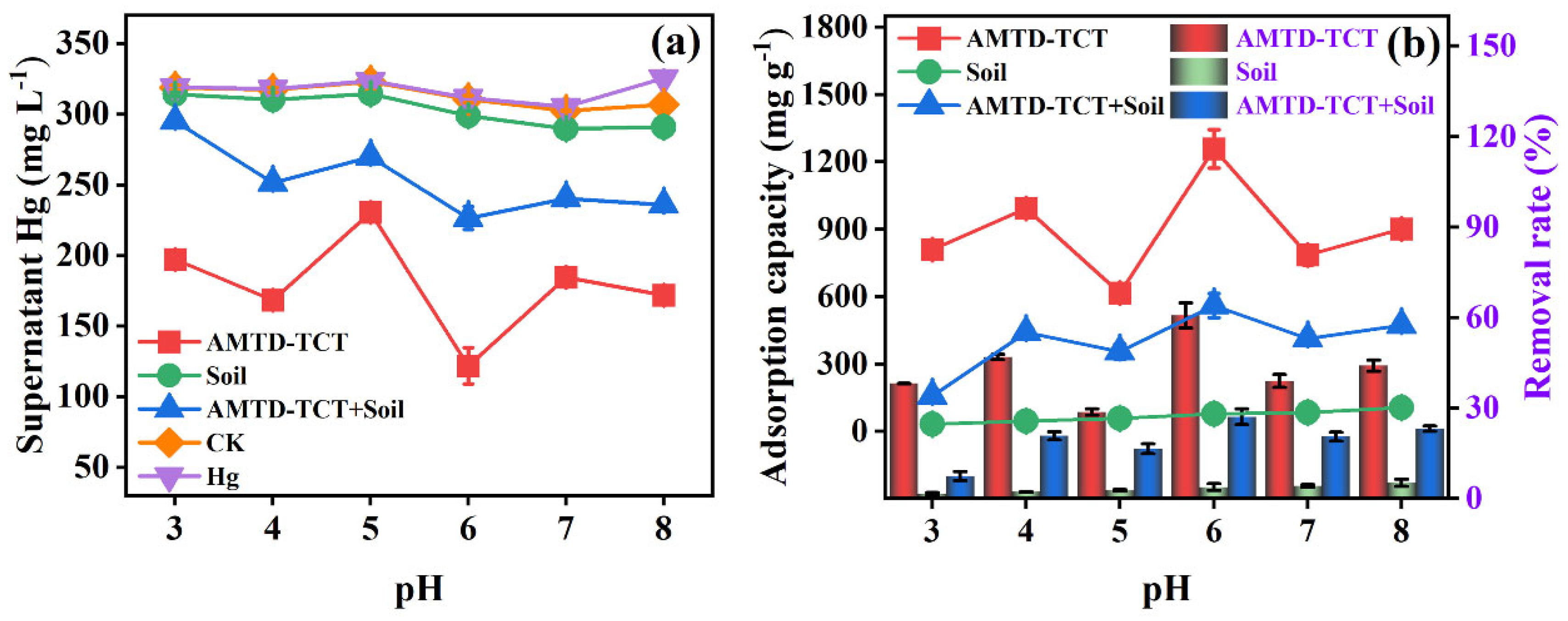

Solution pH plays a critical role in adsorption processes by influencing the protonation state of functional groups, modulating the surface charge of adsorbents, and altering the aqueous speciation of metal ions [60]. For Hg, such effects are particularly pronounced due to the complex equilibrium between its ionic forms. To assess the impact of pH on Hg(II) removal, batch adsorption experiments were conducted across a pH range of 3 to 8.

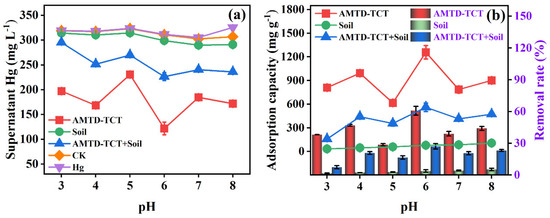

In the control (without adsorbent), the Hg(II) concentration in the supernatant remained essentially unchanged from its initial value after shaking at pH 3–7 (p > 0.492; Table S1), indicating negligible adsorption onto the centrifuge tube walls. At pH 8, however, a slight decrease in Hg(II) concentration was observed (p = 0.004), which is attributed to the precipitation of Hg(OH)2 under alkaline conditions [61] (Figure 6a). These results confirm that the observed removal of Hg(II) in the presence of adsorbents (AMTD-TCT, AMTD-TCT+Soil, or Soil) is due to true adsorption rather than container interactions.

Figure 6.

Concentrations of Hg2+ in supernatants (a) and adsorption capacities and removal efficiencies for Hg2+ (b) of each treatment group under different pH conditions.

The native soil sample exhibited a gradual increase in adsorption capacity from 31.27 to 105.03 mg g−1 as the pH rose from 3 to 8 (Figure 6b). However, analysis of variance (Table S2) indicated that only large pH changes (>3 units) resulted in statistically significant differences, suggesting a relatively low sensitivity of the soil matrix to moderate pH fluctuations. In contrast, AMTD-TCT showed consistently high adsorption capacities across the entire pH range, though its performance was more sensitive to pH variations. The highest adsorption capacity, 1257.65 mg g−1, was achieved at pH 6, highlighting the importance of pH optimization for maximizing the performance of this engineered polymer.

A closer examination of AMTD-TCT’s behavior, with reference to our Visual MINTEQ simulations (Figure S2) for Hg(II) speciation, reveals the underlying mechanism. The relatively low adsorption capacity observed in the highly acidic pH range (pH < 4) can be attributed to several interrelated factors: (1) Competitive Protonation: Under strongly acidic conditions, the high concentration of H+ ions competes directly with Hg(II) species (predominantly Hg2+ and HgCl+, as confirmed in Figure S2) for the nitrogen- and sulfur-containing functional groups (e.g., -NH2, -SH) on AMTD-TCT, effectively reducing the availability of coordination sites for Hg binding. (2) Functional Group Protonation: The amine groups (-NH2) become protonated to form -NH3+ species, while the deprotonation of thiol groups (-SH) is significantly suppressed. This protonation alters the electronic properties of these functional groups and diminishes their ability to coordinate with Hg(II) ions through lone pair electron donation [62]. (3) Hg Speciation: Though Hg2+ and HgCl+ (species with high affinity for AMTD-TCT functional groups) remain predominant in the acidic pH range (Figure S2), the overall adsorption efficiency is compromised by the aforementioned competitive protonation of H+ and protonation of the adsorbent’s functional groups.

As pH increased from 3 to 4, adsorption capacity rose. According to Figure S2, Hg2+ and HgCl+ still account for the majority of Hg(II) species (with a slight decrease in proportion), while neutral HgClOH(aq) begins to appear in small quantities; free Hg(II) species (Hg2+, HgCl+) are still readily captured by AMTD-TCT. Meanwhile, a higher pH reduces the protonation degree of the adsorbent surface, thereby increasing the number of available binding sites. These two factors, together, drive the rise in adsorption capacity. When pH was raised from 4 to 5, capacity declined. HgClOH(aq) becomes the dominant Hg(II) species in this range, and this neutral Hg(II) species has weaker electrostatic attraction and coordination affinity with the adsorbent’s functional groups compared to Hg2+ and HgCl+, which weakens the adsorption effect and leads to a decrease in capacity. Further increasing pH from 5 to 6 again increased capacity. Figure S2 indicates that HgClOH(aq) still maintains a high proportion in this pH range, but the adsorbent surface becomes increasingly deprotonated (the content of protonated -NH3+ decreases, and the deprotonation of -SH is promoted), creating more high-affinity binding sites for Hg(II). The enhancement of functional group activity offsets the slight negative impact of HgClOH(aq) speciation, ultimately increasing adsorption capacity. At pH = 7, capacity decreased once more. HgClOH(aq) and HgCl2(aq) are the main Hg(II) species in this range, and the proportion of Hg(OH)2 begins to increase but has not yet become dominant; these neutral/weakly polar Hg(II) species have lower affinity for AMTD-TCT functional groups than Hg2+ and HgCl+. Additionally, the functional groups on AMTD-TCT are only partially deprotonated, failing to provide sufficient high-affinity binding sites. Despite the initial emergence of Hg(OH)2 (which exhibits precipitation-like behavior), its proportion is too low to offset the aforementioned negative effects, resulting in reduced adsorption capacity. At pH = 8, the adsorption capacity rose again. Under these strongly alkaline conditions, Hg(OH)2 becomes the dominant Hg(II) species; abundant OH− induces the formation of Hg(OH)2, which is captured by AMTD-TCT through precipitation-like interactions. Meanwhile, the thiol and amine groups on AMTD-TCT become fully deprotonated, providing numerous high-affinity binding sites. The synergistic effect of Hg(OH)2 precipitation and fully activated functional groups significantly enhances adsorption capacity.

The AMTD-TCT+Soil composite exhibited intermediate behavior, with Hg(II) adsorption capacities ranging from 156.58 to 560.93 mg g−1. These values are significantly higher than those of unmodified soil but remain lower than those of pure AMTD-TCT. Notably, the composite’s adsorption trend mirrored that of AMTD-TCT, though with reduced amplitude in response to pH changes (Figure 6b, Table S3). This suggests that the soil matrix exerts a buffering effect, dampening the pH sensitivity imparted by AMTD-TCT. The synergy between the high-affinity binding sites of AMTD-TCT and the buffering capacity of soil results in enhanced and more stable adsorption across the tested pH range. Based on the performance of all three adsorbents, pH = 6 was identified as the optimal condition for Hg(II) uptake and was therefore selected for subsequent experiments.

Effects of initial Hg concentrations

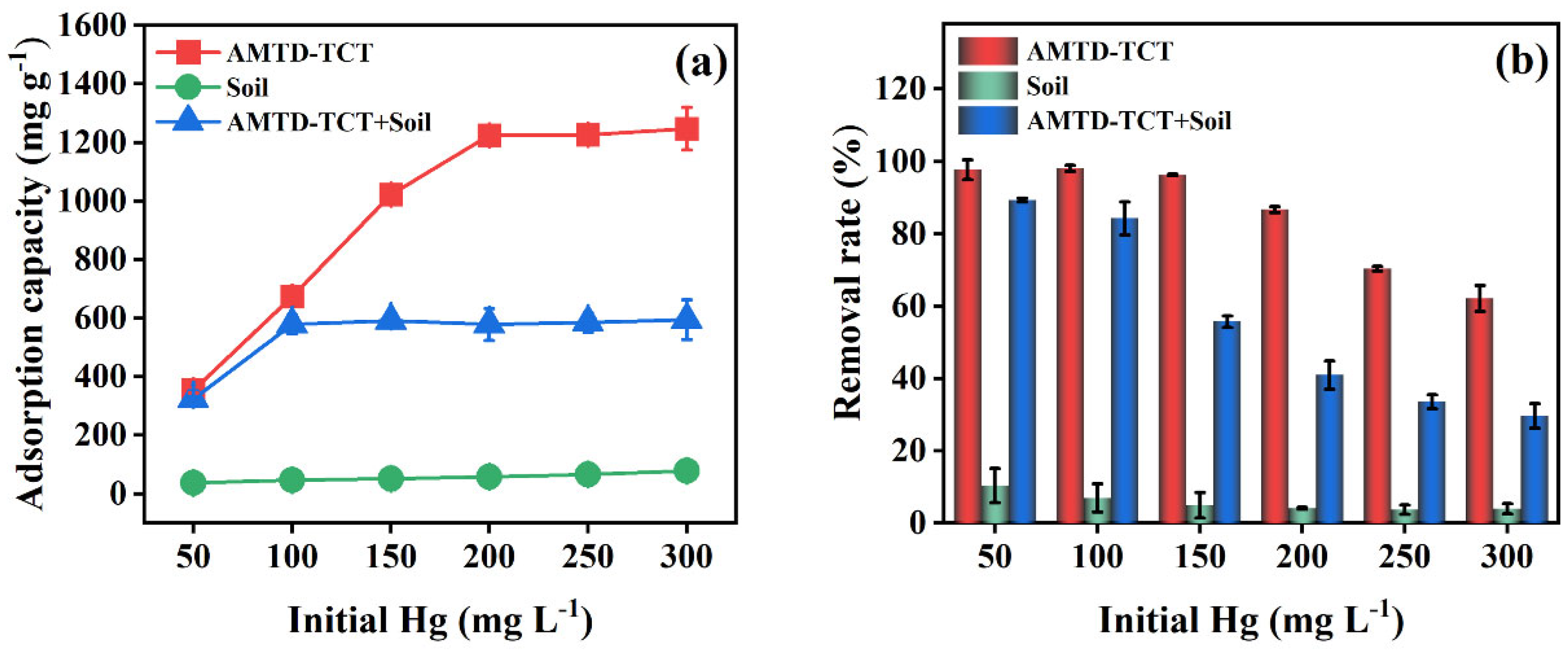

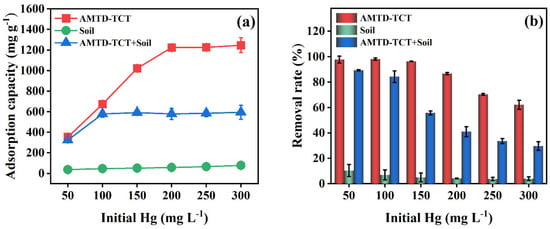

The initial concentration of heavy metal ions is a critical parameter affecting the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency of adsorbents. To investigate this effect, Hg(II) solutions with concentrations ranging from 50 to 300 mg L−1 were tested using three adsorbents: AMTD-TCT, native soil, and their 1:1 (w/w) composite.

As shown in Figure 7a, all adsorbents exhibited increasing Hg(II) uptake with rising initial concentrations, eventually reaching a saturation plateau. AMTD-TCT demonstrated the highest adsorption capacity, ranging from 1224.21 to 1247.03 mg g−1, and showed no significant increase beyond 200 mg L−1 (p > 0.486; Table S4). In contrast, unmodified soil showed much lower capacities (52.40–78.69 mg g−1), with minimal variation across the same concentration range (p > 0.154). The AMTD-TCT+Soil composite exhibited intermediate adsorption capacities (578.29–594.70 mg g−1), leveling off above 100 mg L−1 (p > 0.703).

Figure 7.

Adsorption capacities (a) and removal efficiencies (b) of Hg2+ by each treatment group at different initial Hg(II) concentrations.

At each concentration, AMTD-TCT significantly outperformed the composite and native soil (Figure 7a). Statistical analysis confirmed that these differences were highly significant (p < 0.003; Table S5), underscoring the effectiveness of AMTD-TCT incorporation in enhancing the adsorption capacity of soil-based systems.

Removal efficiency trends (Figure 7b) followed the order AMTD-TCT > AMTD-TCT+Soil > Soil across all initial concentrations. For all adsorbents, removal efficiencies declined as Hg(II) concentration increased, reflecting saturation of available binding sites. At lower concentrations, the number of active sites is sufficient to sequester most Hg(II), while at higher concentrations, the ratio of Hg(II) ions to binding sites increases, resulting in diminished removal rates.

Notably, AMTD-TCT maintained high adsorption capacity up to 200 mg L−1, whereas the composite reached saturation around 100 mg L−1. This suggests that AMTD-TCT possesses a greater density of accessible binding sites and higher affinity for Hg(II), enabling superior performance under elevated pollutant loads. Based on these observations, 300 mg L−1 was selected as the standard initial concentration for all subsequent experiments, ensuring full expression of each material’s adsorption potential.

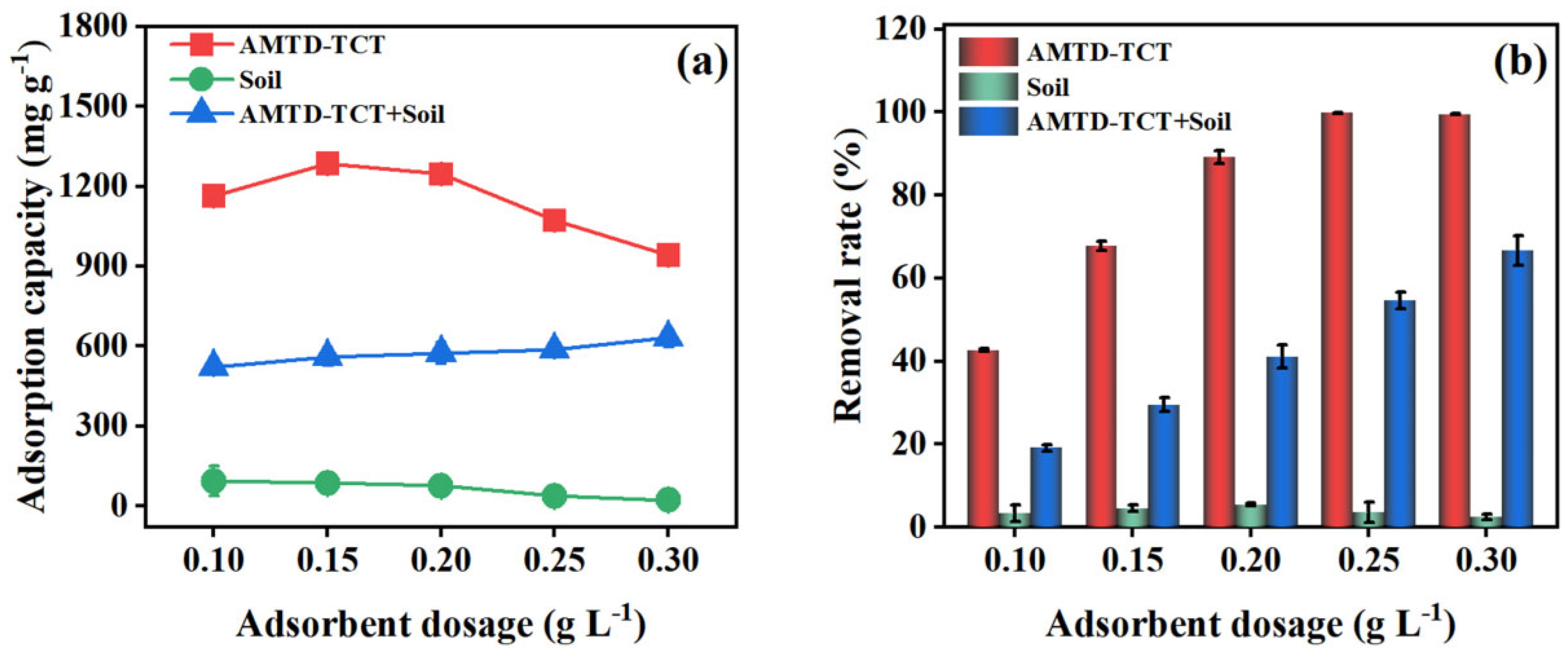

Effects of adsorbent dosages

As illustrated in Figure 8a and Table S6, significant differences (p < 0.002) were observed in the adsorption capacity of AMTD-TCT as the adsorbent dosage varied between 0.1 and 0.3 g L−1. At lower adsorbent dosages, higher Hg2+ concentrations in solution increase the probability of contact between active surface sites (e.g., amino and thiol groups) and Hg2+ ions, leading to a greater utilization of active sites per unit mass of adsorbent, thus increasing adsorption capacity. However, with an increasing adsorbent dosage, the concentration of Hg2+ in solution gradually decreased. When the adsorbent dosage surpassed a critical threshold, the Hg2+ concentration in solution became insufficient to occupy all available active sites, resulting in a decrease in adsorption capacity.

Figure 8.

Adsorption capacity (a) and removal efficiency (b) of Hg2+ by different treatment groups under varying adsorbent dosages.

The removal efficiencies (Figure 8b) varied accordingly. At adsorbent dosages of 0.1–0.15 g L−1, the removal efficiency ranged from 42.684% to 67.811%, indicating a substantial amount of Hg2+ remaining in solution and sufficient to achieve saturation of adsorption sites. At higher dosages (0.2–0.3 g L−1), removal efficiencies increased significantly, ranging between 89.218% and 99.826%, with only trace Hg2+ remaining in solution. Under these conditions, a large number of adsorption sites remained unsaturated, leading to a lower adsorption capacity per unit mass.

As indicated in Table S6, Soil alone showed no significant differences (p > 0.056) in adsorption capacity when the adsorbent dosage was increased from 0.1 to 0.3 g L−1. Similarly, AMTD-TCT+Soil exhibited no significant differences (p > 0.065) in adsorption capacity within the dosage range of 0.15–0.3 g L−1. Within the dosage range of 0.1–0.3 g L−1, AMTD-TCT+Soil exhibited adsorption capacities and removal efficiencies intermediate between pure AMTD-TCT and pure Soil. Additionally, significant differences were observed between AMTD-TCT+Soil and Soil (Table S7), highlighting the beneficial impact of adding AMTD−TCT to Soil, resulting in enhanced Hg2+ adsorption.

According to Figure 8a, the AMTD-TCT treatment group achieved its highest adsorption capacity at an adsorbent dosage of 0.15 g L−1. Considering the lack of significant difference in the AMTD-TCT+Soil group within the 0.15–0.3 g L−1 range (Table S6), along with economic and environmental considerations, an adsorbent dosage of 0.15g L−1 was selected for subsequent experiments.

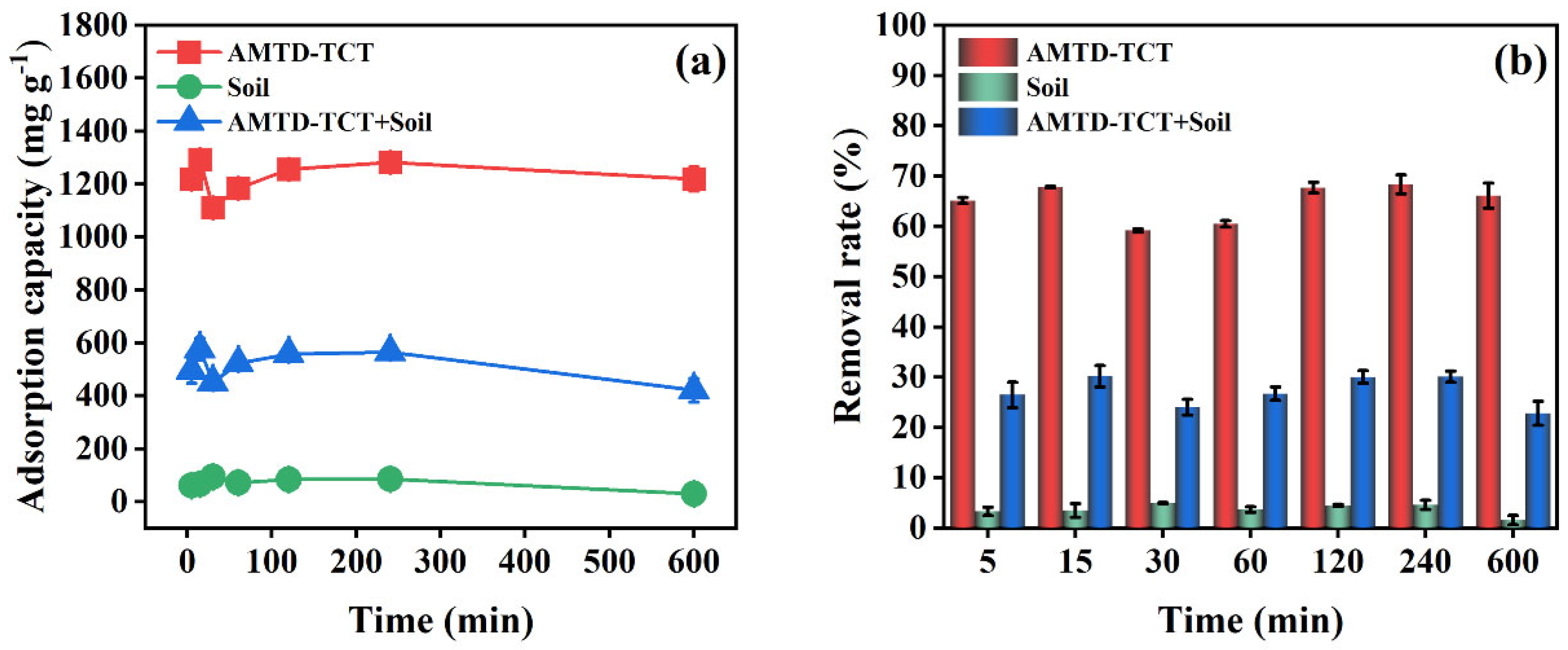

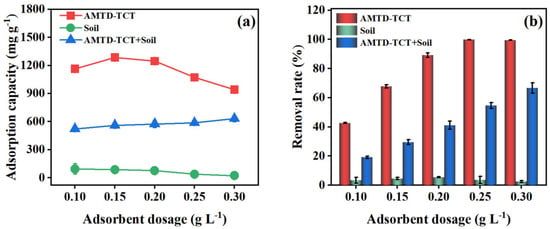

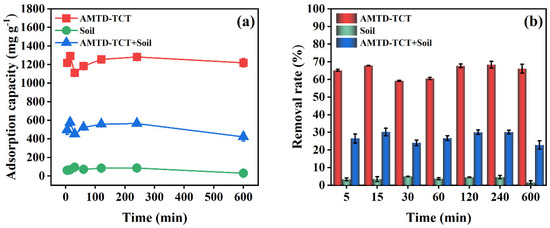

Effects of contact time

To investigate the influence of contact time on adsorption behavior, 0.15 g L−1 of each adsorbent (AMTD-TCT, Soil, and AMTD-TCT+Soil) was introduced into 20 mL of a 300 mg L−1 Hg(II) solution (pH 6) at 25 °C. The mixtures were shaken for 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, or 600 min, and the adsorption capacities and removal efficiencies were subsequently determined (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Adsorption capacity (a) and removal efficiency (b) of Hg2+ by different treatment groups under varying adsorption times.

As shown in Figure 9a, both AMTD-TCT and AMTD-TCT+Soil exhibited rapid initial uptake, with adsorption capacities peaking at 15 min (1292.60 mg g−1 and 576.01 mg g−1, respectively). A transient decline followed, with AMTD-TCT dropping to 1109.83 mg g−1 at 30 min, before a gradual rebound and eventual stabilization. By 600 min, adsorption equilibrium was reached, with capacities slightly reduced to 420.69 mg g−1 for the composite. In contrast, native Soil showed a slower and more gradual adsorption profile, reaching a maximum capacity of 93.91 mg g−1 at 30 min, followed by a steady decrease to 29.40 mg g−1 at 600 min.

The corresponding removal efficiencies (Figure 9b) mirrored these trends, reinforcing the time-dependent adsorption dynamics observed in Figure 9a. Throughout the entire time course, AMTD-TCT and its composite consistently outperformed Soil, maintaining significantly higher adsorption efficiencies. Notably, the AMTD-TCT+Soil treatment exhibited a marked improvement over Soil alone (Table S8), confirming the synergistic effect of incorporating AMTD-TCT into the soil matrix.

Analysis of variance (Table S9) revealed no statistically significant differences in adsorption capacities among the three treatments between 120 and 240 min (p > 0.308), suggesting that near-equilibrium conditions had been achieved by 120 min. Additionally, within each treatment group, significant differences among different contact times were confirmed (Table S10), further supporting the time-dependent adsorption behavior observed. Therefore, 120 min was selected as the optimal contact time for subsequent adsorption and desorption experiments.

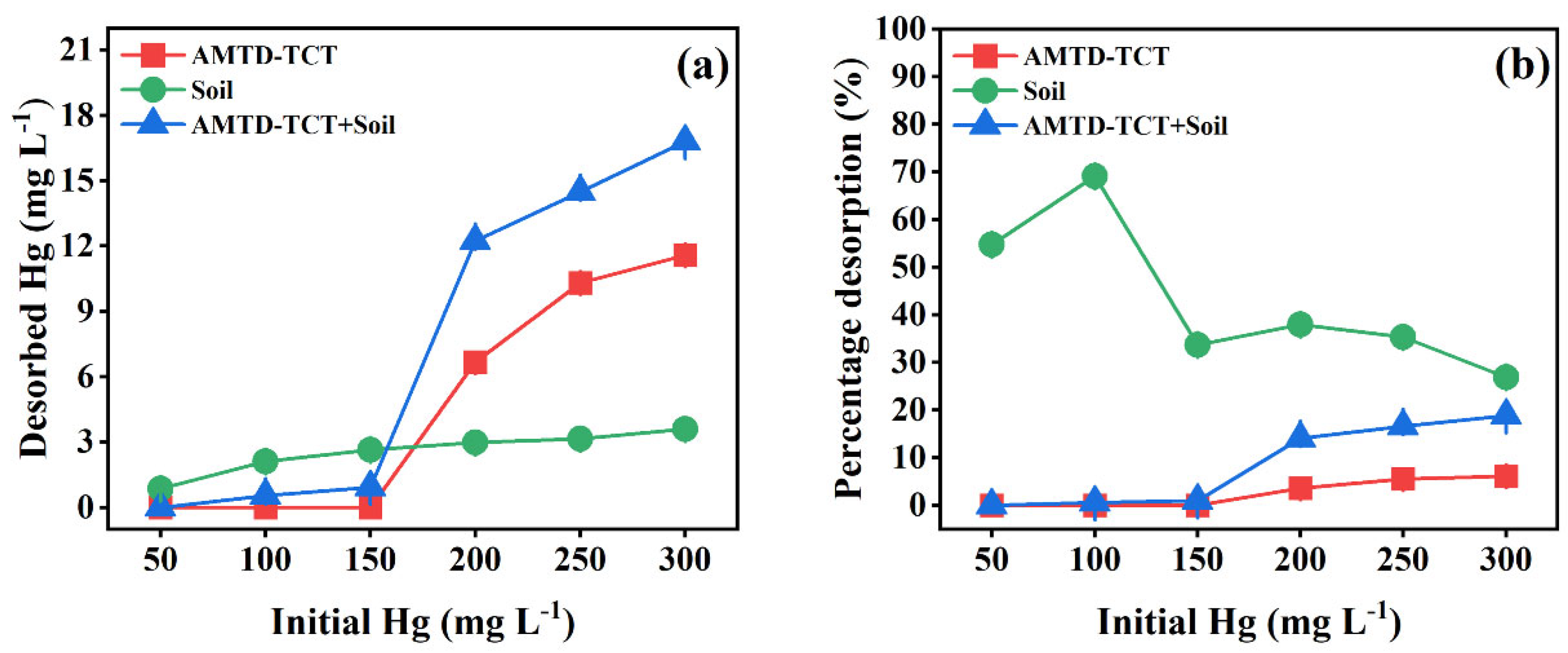

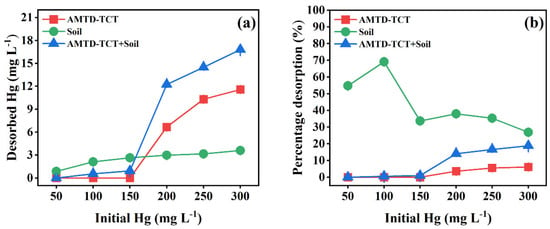

3.3. Desorption Characteristics of Hg(II) from AMTD-TCT

The desorption rate is a key indicator of an adsorbent’s ability to immobilize heavy metal ions, with lower desorption values signifying stronger binding affinity and greater retention stability. In this study, desorption experiments were conducted to evaluate the ability of AMTD-TCT, Soil, and their composite to retain Hg(II) following adsorption.

For each treatment, 0.15 g L−1 of adsorbent was added to 20 mL of Hg(II) solution (pH 6) with initial concentrations ranging from 50 to 300 mg L−1. The suspensions were shaken at 25 °C for 120 min to achieve adsorption equilibrium. After removal of the supernatant, the Hg-loaded adsorbents were leached with 20 mL of 0.01 mol L−1 NaNO3 solution under the same conditions. The concentration of Hg(II) in the leachate was then measured, and the corresponding desorption rates were calculated (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Leached Hg concentration (a) and desorption rate (b) of different treatment groups under 0.01 mol L−1 NaNO3 conditions.

As shown in Figure 10a, the leachate Hg(II) concentrations increased with the initial loading concentration for all three treatments. At the highest initial Hg(II) concentration (300 mg L−1), the corresponding leachate concentrations were 3.60 mg L−1 for Soil, 11.59 mg L−1 for AMTD-TCT, and 16.80 mg L−1 for the AMTD-TCT+Soil composite. Figure 10b further reveals that desorption rates followed the order: Soil > AMTD-TCT+Soil > AMTD-TCT, across the entire concentration range tested. For instance, at 300 mg L−1, the desorption rates were 26.96% for Soil, 18.87% for AMTD-TCT+Soil, and only 6.21% for AMTD-TCT.

These results clearly demonstrate that AMTD-TCT exhibits superior immobilization performance, attributed to its high-affinity binding sites and strong chemisorption mechanisms. The significant reduction in desorption rates when AMTD-TCT is incorporated into the soil matrix indicates enhanced stabilization of Hg(II) compared to Soil alone. Therefore, AMTD-TCT not only facilitates high-capacity Hg(II) uptake but also ensures robust retention under mild leaching conditions.

3.4. Adsorption Mechanisms

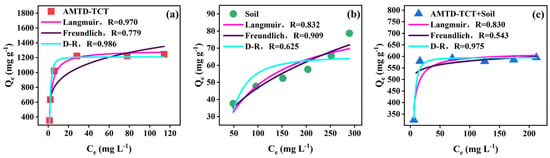

Adsorption isotherm and adsorption kinetic models

Adsorption isotherms are crucial tools for characterizing solid-liquid interface adsorption behavior, describing the relationship between the adsorbate concentration and the equilibrium adsorption capacity at a constant temperature [40]. A key output of these models is the saturated adsorption capacity (qm), which reflects the maximum loading potential of an adsorbent and serves as a benchmark for evaluating adsorption performance [63]. Moreover, isotherm modeling provides insights into the nature and strength of adsorbate-adsorbent interactions, the distribution of active sites, and the underlying adsorption mechanisms. These insights are instrumental for selecting suitable adsorbents, optimizing operational conditions, and designing regeneration protocols in water treatment applications [64].

Among the various models, the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms are the most widely applied in heavy metal adsorption studies. The Langmuir model is based on three primary assumptions [38,39]: (i) the adsorption surface is homogeneous; (ii) adsorption occurs as a monolayer with no interaction between adsorbed molecules; and (iii) adsorption and desorption processes are in dynamic equilibrium. Under these conditions, the Langmuir equation provides a theoretical qm value and is generally suitable for chemisorption-dominated systems with uniformly distributed adsorption sites.

In contrast, the Freundlich model is empirical and does not assume monolayer coverage or surface homogeneity. It accounts for multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces and is particularly useful in describing systems governed by physical adsorption or adsorbents with structural and energetic heterogeneity [40,41].

In the present study, both Langmuir and Freundlich models were employed to fit the equilibrium data (Section 3.2, ‘Effects of initial Hg concentrations’) and the results are summarized in Figure 11 and Table S11. For the AMTD-TCT and AMTD-TCT+Soil treatments, the Langmuir model yielded superior fits (R2 = 0.970 and 0.830, respectively), indicating that adsorption occurs predominantly through monolayer formation on relatively uniform surfaces. The Langmuir-derived maximum adsorption capacities (qm) for AMTD-TCT and AMTD-TCT+Soil were 1297.81 mg g−1 and 614.74 mg g−1, respectively, values that closely match the experimental capacities of 1247.03 mg g−1 and 594.70 mg g−1. This close agreement supports the assumption of homogeneous adsorption sites and a chemisorption-driven mechanism.

Figure 11.

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm fitting models for (a) AMTD-TCT, (b) Soil, and (c) AMTD-TCT+Soil treatment groups.

For the Soil-only treatment, both the Langmuir (R2 = 0.832) and Freundlich (R2 = 0.909) models provided acceptable fits, with Langmuir estimating a qm of 90.50 mg g−1, in good agreement with the experimental value of 78.69 mg g−1. The distinct fitting behaviors observed for different treatment groups in Figure 11 can be attributed to fundamental differences in their surface properties and adsorption mechanisms. For AMTD-TCT, the excellent fit to the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.970) indicates relatively homogeneous surface sites and monolayer adsorption dominated by strong chemisorption. This is consistent with its designed structure featuring abundant, uniformly distributed nitrogen/sulfur coordination sites that provide high-affinity binding for Hg(II) through coordination bonds and ion exchange. In contrast, natural soil possesses a highly heterogeneous surface comprising various mineral oxides, organic matter, and clay minerals with binding sites of different energies. This heterogeneity explains why the Freundlich model provided a better fit (R2 = 0.909) for soil compared to the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.832), suggesting multilayer adsorption on energetically heterogeneous surfaces. However, the concurrent acceptable fit to the Langmuir model indicates that monolayer adsorption also occurs on specific, relatively uniform surface patches within the soil matrix. The AMTD-TCT+Soil composite exhibited intermediate behavior, with the Langmuir model providing a better description than the Freundlich model. This suggests that the incorporation of AMTD-TCT introduces sufficient homogeneous, high-affinity sites that begin to dominate the overall adsorption behavior, making the composite system more Langmuir-like while still retaining some characteristics of the native soil matrix. These findings suggest that Hg(II) adsorption onto unmodified soil involves both monolayer and multilayer processes, consistent with a heterogeneous surface containing a mixture of binding sites.

The D-R model was further employed to characterize the porosity-related adsorption behavior and estimate the mean free energy of adsorption. As summarized in Figure 11 and Table S11, the D-R model provided excellent fits for both AMTD-TCT (R2 = 0.986) and its soil composite (R2 = 0.975), confirming the microporous nature of the adsorption process. The calculated mean free energy values (E) were 0.365 kJ mol−1 for AMTD-TCT and 0.146 kJ mol−1 for the composite. While these values are relatively low, they should be interpreted in conjunction with the direct spectroscopic evidence from XPS and FTIR, which unequivocally demonstrate the formation of strong chemical bonds between Hg(II) and the N/S functional groups in AMTD-TCT.

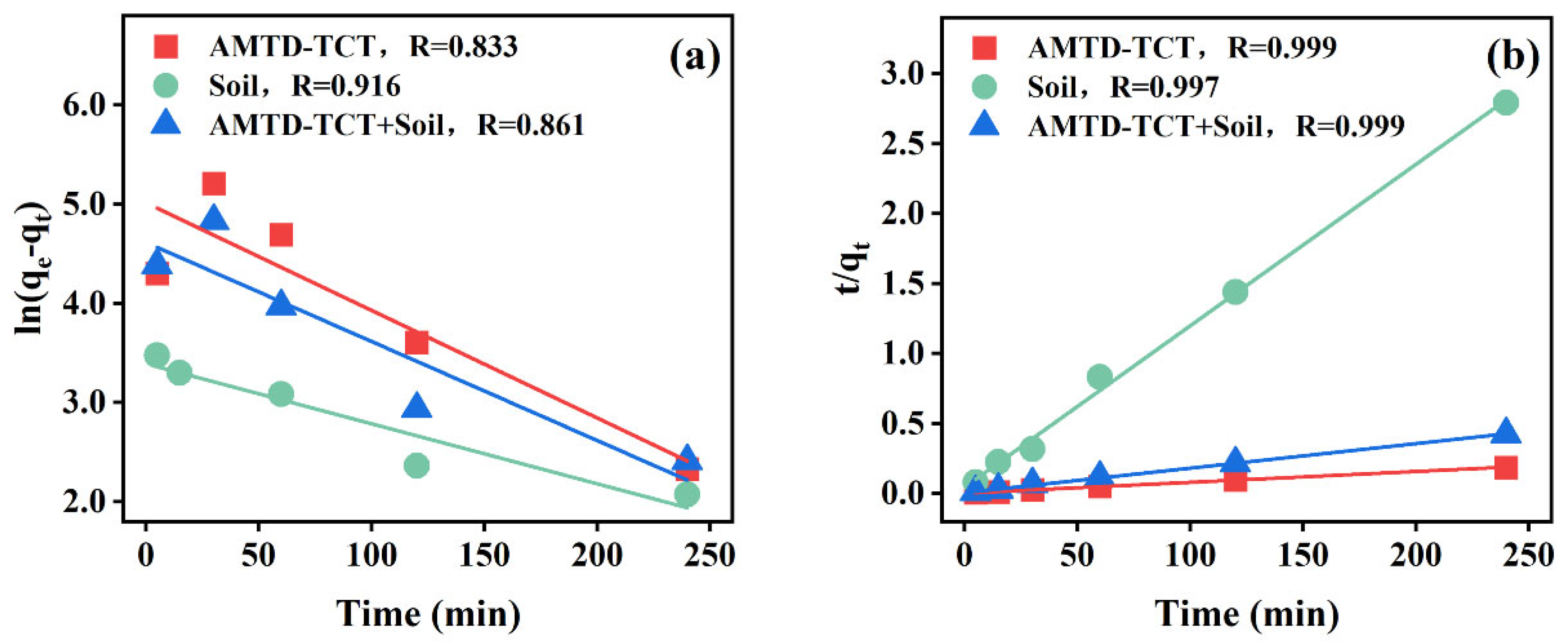

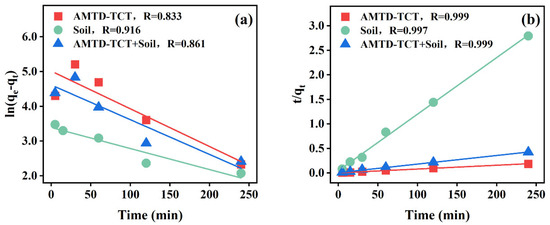

In addition to equilibrium modeling, kinetic analysis reveals the time-dependent nature of Hg(II) uptake and offers further insight into rate-controlling steps and adsorption mechanisms. Adsorption kinetics provides crucial insight into mass transfer processes at the solid-liquid interface by evaluating how the amount of adsorbed species changes over time. Kinetic analysis not only yields rate constants but also helps identify rate-limiting steps and dominant adsorption mechanisms. Among the commonly used kinetic models, the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) equations are particularly prevalent in describing heavy metal adsorption behavior.

The PFO model is generally associated with diffusion-controlled processes and is often used to describe the initial stages of adsorption where intra-particle diffusion or liquid-film resistance predominates, particularly in systems involving porous adsorbents. In contrast, the PSO model assumes that chemisorption is the rate-determining step, involving electron exchange or sharing between the adsorbent’s active sites and the adsorbate species [65,66].

In the present study, both PFO and PSO models were applied to fit the time-dependent adsorption data for AMTD-TCT, Soil, and their composite using linear regression analysis. The fitted curves and corresponding kinetic parameters are shown in Figure 12 and Table S12. The correlation coefficients (R2) indicate that all three systems are more accurately described by the PSO model, with R2 values of 0.999 (AMTD-TCT), 0.997 (Soil), and 0.999 (AMTD-TCT+Soil).

Figure 12.

Pseudo-first-order kinetic fitting models (a) and pseudo-second-order kinetic fitting models (b) for different treatment groups.

The theoretical adsorption capacities (qe) predicted by the PSO model, 1289.49 mg g−1 for AMTD-TCT, 86.73 mg g−1 for Soil, and 571.43 mg g−1 for the composite, closely match the experimentally determined values (1292.60, 93.91, and 576.01 mg g−1, respectively). This excellent agreement further supports the applicability of the PSO model to describe Hg(II) uptake in these systems. Based on these results, it can be concluded that chemisorption is the predominant mechanism governing Hg(II) removal by AMTD-TCT and its composite formulations, likely involving strong coordination interactions and electron exchange with surface functional groups [67].

Importantly, the conclusion that chemisorption is the dominant mechanism is not solely based on kinetic model fitting but is robustly supported by multiple independent lines of evidence:

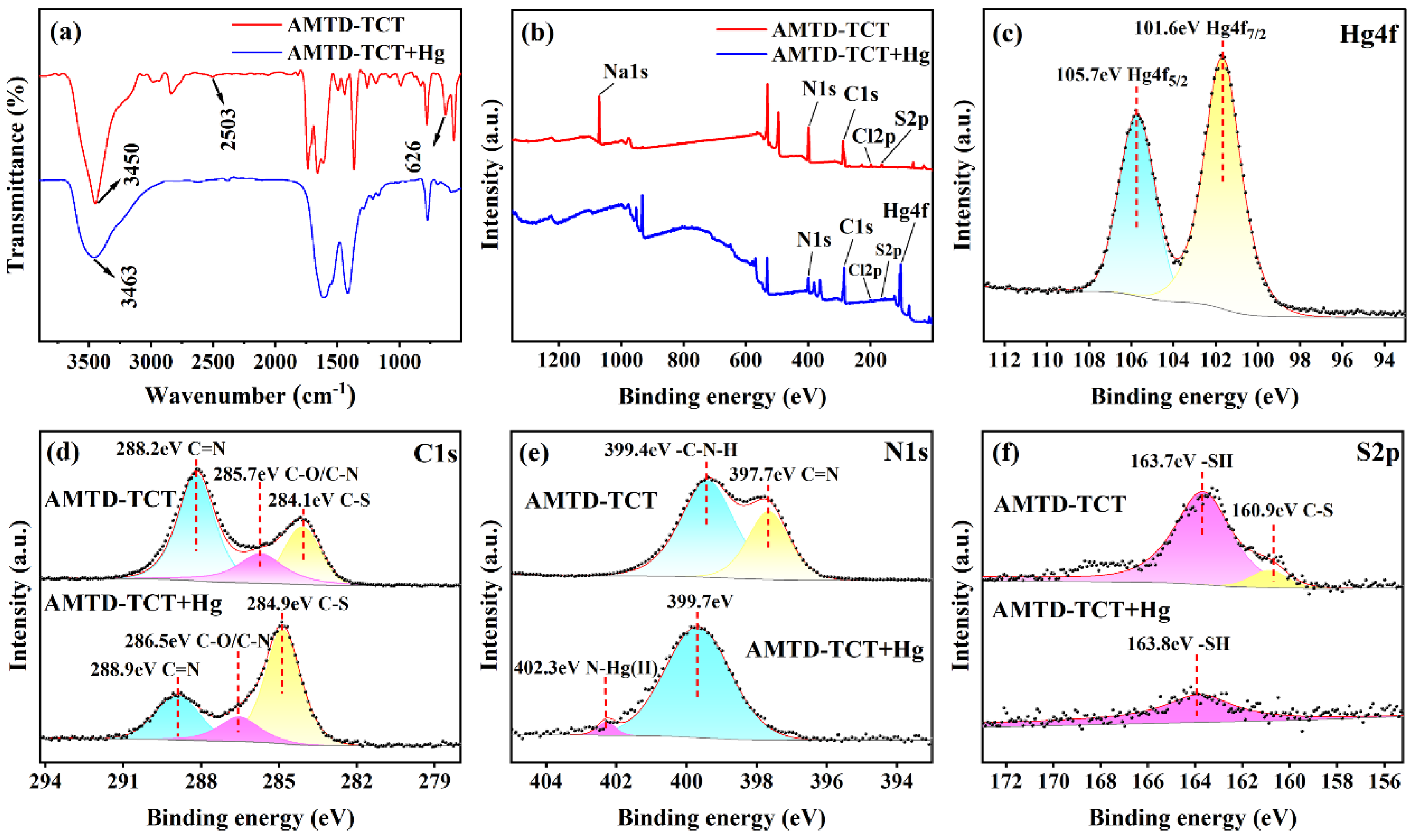

(1) X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): The disappearance of the Na 1s peak coupled with the emergence of Hg 4f peaks, along with the distinct binding energy shifts in the S 2p and N 1s regions (Figure 13b–f), provide direct evidence for the formation of strong S-Hg and N-Hg coordination bonds and the occurrence of ion exchange.

Figure 13.

FTIR spectra of AMTD-TCT before and after Hg adsorption (a), and XPS spectra of AMTD-TCT before and after Hg adsorption (b–f).

(2) Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): The disappearance or significant weakening of characteristic peaks corresponding to -SH (2503 cm−1), C-S (626 cm−1), and N-H/N-H2 (3450 cm−1) groups after Hg(II) adsorption (Figure 13a) confirms the direct involvement of these functional groups in binding Hg(II) through coordination.

(3) High Affinity and Low Desorption: The exceptionally high adsorption capacity (1257.7 mg g−1) combined with the minimal desorption rates (<6.21%) observed under mild leaching conditions (Section 3.3) are characteristic of strong, irreversible chemical binding rather than weak physical adsorption.

Collectively, this convergent evidence from spectroscopy, equilibrium studies, and desorption behavior unequivocally supports the assignment of a chemisorption-driven adsorption mechanism.

Microstructural characterization of AMTD-TCT before and after Hg(II) adsorption

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to investigate the chemical structure of AMTD-TCT before and after Hg(II) adsorption, revealing distinct changes in its vibrational features (Figure 13a). Specifically, the C-S stretching band at 626 cm−1 and the -SH stretching band at 2503 cm−1, both characteristic of the pristine polymer, disappeared following Hg(II) exposure. Additionally, the broad absorption band centered at 3450 cm−1, associated with -NH and -NH2 groups, was significantly weakened after adsorption. These spectral changes strongly suggest that the -SH, -C-S, -NH, and -NH2 functional groups are actively involved in binding Hg(II), likely through coordination or complexation mechanisms, as evidenced by the disappearance or attenuation of their corresponding peaks.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provided additional evidence supporting the Hg(II) adsorption mechanism (Figure 13b–f). In the survey spectrum of pristine AMTD-TCT (Figure 13b), a distinct Na 1s peak was observed, attributed to residual NaOH from the synthesis process. Following Hg(II) exposure, this Na peak disappeared, and two prominent Hg 4f peaks emerged, suggesting that Hg(II) replaced Na+ through an ion exchange mechanism. The Na+ ions are likely associated with deprotonated functional groups in the polymer, such as the nitrogen atoms in the triazine rings or other anionic sites formed during the synthesis at high pH.

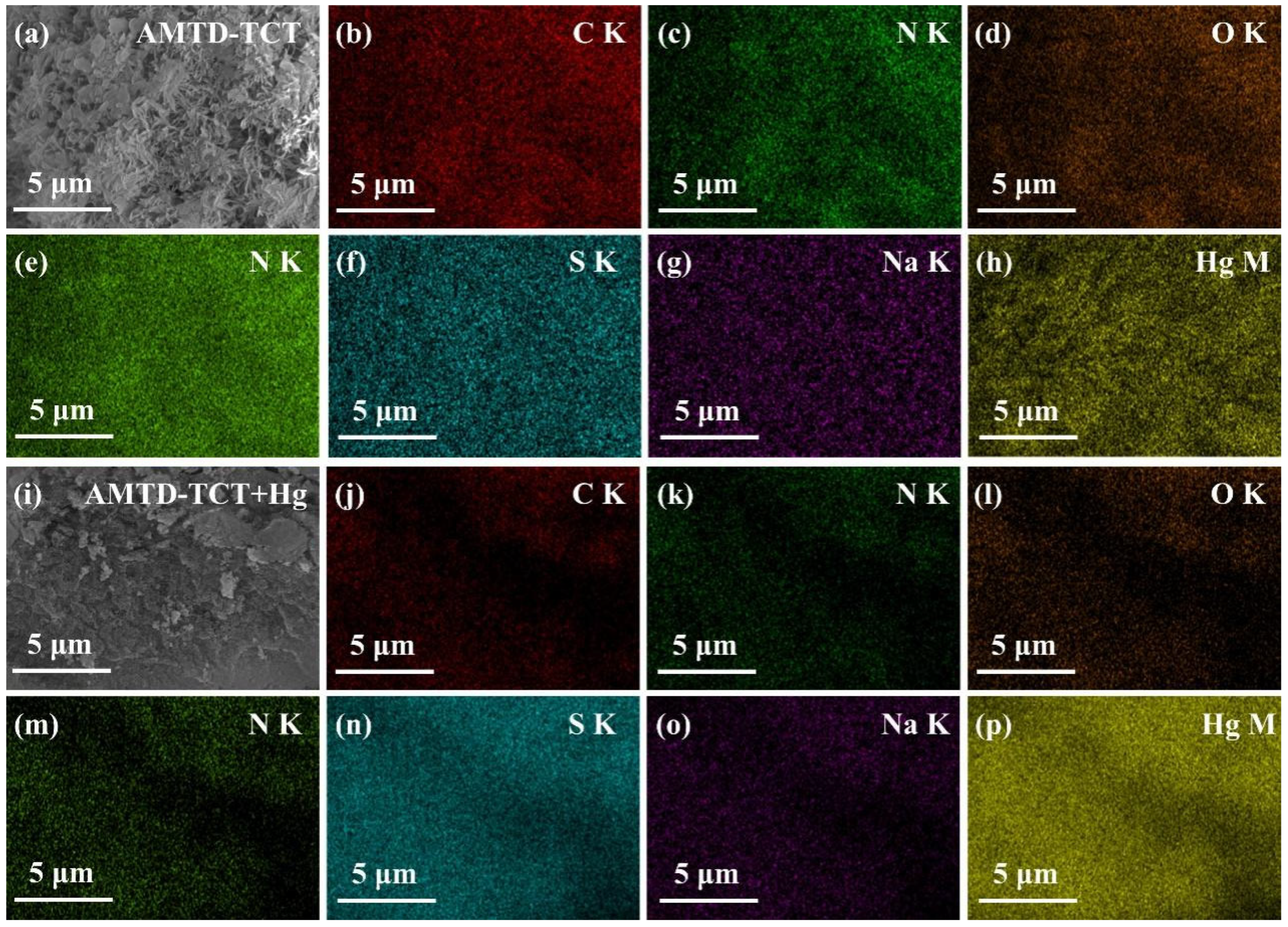

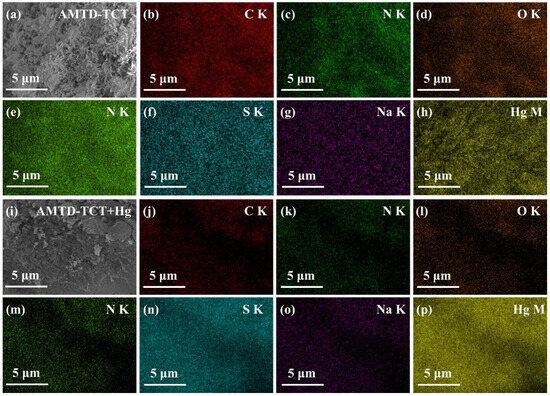

To verify that this change signifies an ion exchange mechanism and not solely complexation, we analyzed the elemental composition and distribution. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (Figure S3) provided quantitative evidence, revealing a sharp decrease in Na atomic percentage from 13.53% to 0.87%, coupled with a significant increase in Hg from 0.52% to 16.71% after adsorption. This substantial release of Na+, concurrent with the nearly stoichiometric uptake of Hg2+, is a hallmark of ion exchange. Furthermore, elemental mapping (Figure 14) visually corroborates this process, showing the homogeneous distribution of Hg across the polymer surface and the concomitant decrease in Na signal after adsorption. The combined evidence from EDS (quantitative change), elemental mapping (spatial distribution), and the complete disappearance of the Na 1s signal in XPS survey spectra provides a multi-faceted and robust verification of the ion exchange between Na+ and Hg2+. The Na+ ions, originally present from synthesis, are likely electrostatically associated with deprotonated sites. While coordination occurs simultaneously, this significant Na+ release confirms ion exchange as a key pathway.

Figure 14.

Elemental mapping images of AMTD-TCT before (a–h) and after (i–p) Hg adsorption.

High-resolution analysis of the Hg 4f region (Figure 13c) revealed two characteristic peaks at 101.1 eV and 105.1 eV, corresponding to Hg 4f7/2 and Hg 4f5/2, respectively [54], confirming successful incorporation of Hg(II) into the polymer matrix. Additional insights were obtained from the C 1s and N 1s spectra. In the C 1s spectrum (Figure 13d), peaks at 288.2 eV, 285.7 eV, and 284.1 eV, assigned to C=N, C-N/C-O, and C-S bonds, respectively, shifted to 288.9 eV, 286.5 eV, and 284.9 eV after Hg(II) adsorption [45,54], indicating alterations in the electronic environment and chemical bonding of these groups.

Similarly, the N 1s spectrum (Figure 13e) exhibited two peaks at 397.7 eV and 399.4 eV in the pristine material, corresponding to C=N (thiadiazole ring) [68] and C-N-H moieties [69], respectively. Upon Hg(II) adsorption, the 397.7 eV peak disappeared, and a new peak appeared at 402.3 eV, consistent with the formation of an N-Hg coordination complex [70].

In the S 2p spectrum (Figure 13f), the C-S peak at 160.9 eV, present prior to adsorption, was no longer detectable following Hg(II) uptake, while the -SH-related peak exhibited a slight shift from 163.7 to 163.8 eV. The loss of the C-S signal suggests the formation of S-Hg bonds [70], and the shift in the -SH peak indicates strong Hg-S interactions [57].

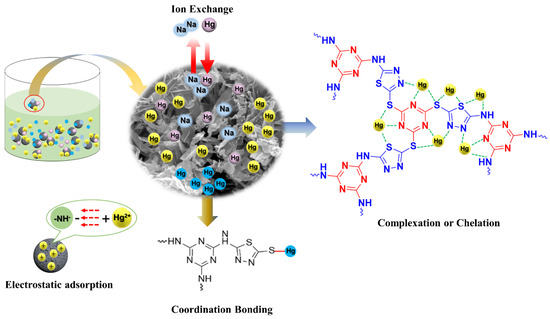

Collectively, the FTIR and XPS analyses reveal that Hg(II) adsorption onto AMTD-TCT proceeds via two cooperative mechanisms: (i) ion exchange between Na+ and Hg(II), and (ii) chelation of Hg(II) through coordination with nitrogen- and sulfur-containing functional groups within the polymer matrix. These synergistic interactions substantially enhance the material’s Hg(II) sequestration efficiency, thereby improving both the standalone and soil composite adsorption performance of AMTD-TCT.

In this study, the morphological features of AMTD-TCT before and after Hg(II) adsorption were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure 15). Prior to adsorption, the material exhibited a flake-like morphology composed of irregularly stacked layers with a rough surface and abundant pores (Figure 15a,b). Following Hg(II) exposure, the structure became more compact, transforming into a block-like morphology with a similarly rough but less porous appearance (Figure 15c,d).

Figure 15.

SEM images of AMTD-TCT: (a) before Hg adsorption; (b) higher-magnification image of the area indicated by the red square in (a); (c) after Hg adsorption; (d) higher-magnification image of the area indicated by the red square in (c).

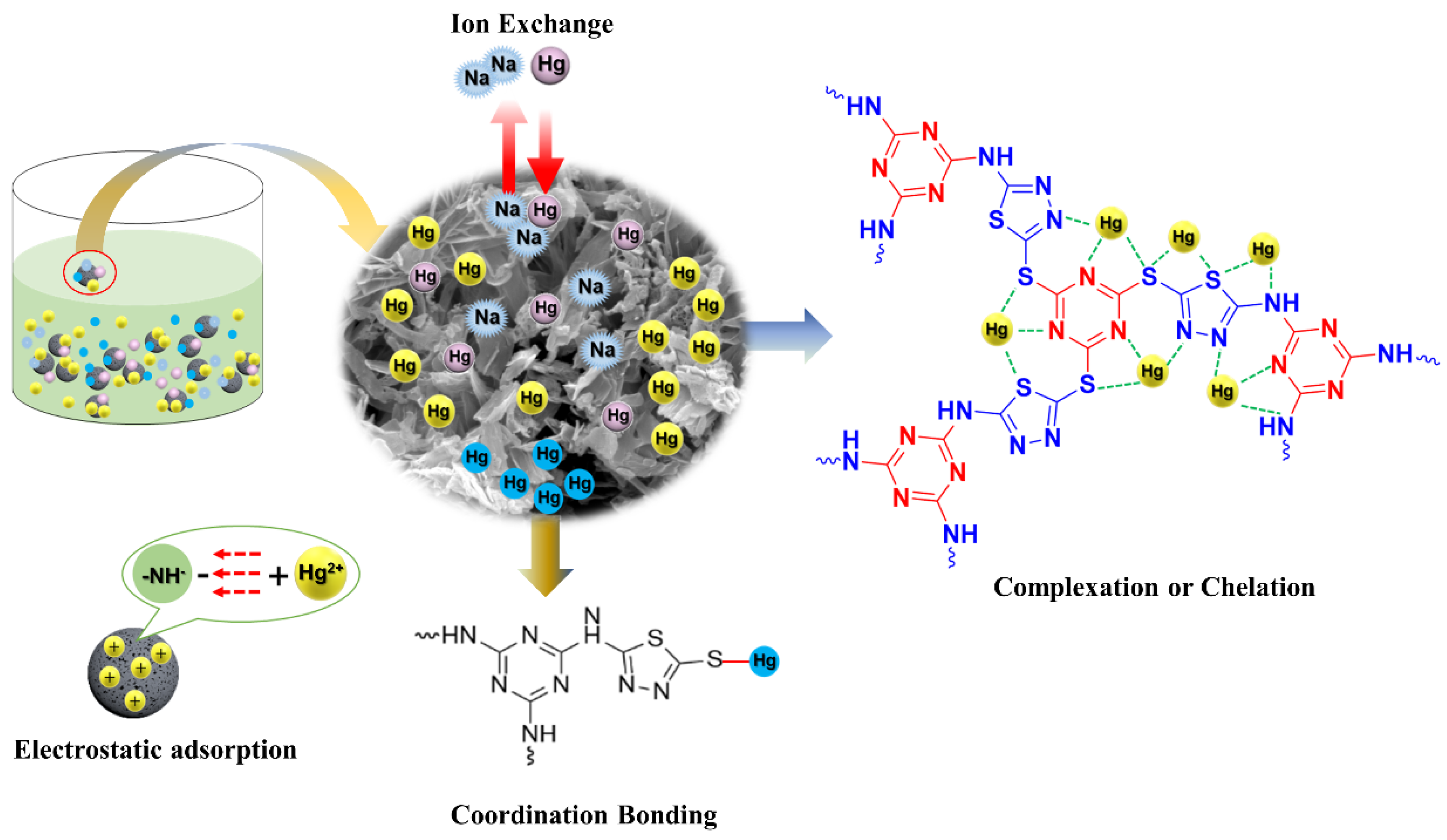

Understanding the adsorption mechanism is essential for elucidating the structure-function relationship and guiding the rational design of high-performance adsorbents. In this study, combined analysis of adsorption isotherms and kinetics indicates that Hg(II) uptake by AMTD-TCT is primarily governed by chemisorption.

Spectroscopic characterization using FTIR and XPS confirms that Hg(II) binds through interactions with nitrogen- and sulfur-containing functional groups within the polymer framework, specifically -NH2, -NH-, -SH, and C-S moieties. Morphological and textural analyses by SEM and BET further reveal that the hierarchical pore structure and high surface area of AMTD-TCT contribute to the availability of abundant active sites, thereby facilitating efficient mass transfer and metal ion capture.

In addition, elemental analysis via EDS shows a substantial amount of Na+ in the pristine material, which is largely replaced by Hg(II) after adsorption, supporting the occurrence of an ion exchange mechanism. As illustrated in Figure 16, the overall adsorption process involves multiple, cooperative interactions: (i) coordination bonding between -SH groups and Hg(II); (ii) surface complexation or chelation via -NH2, -NH-, -SH, and C-S functionalities; (iii) electrostatic attraction at negatively charged sites resulting from deprotonated amine groups; and (iv) ion exchange between Na+ and Hg(II). Together, these synergistic pathways explain the exceptional adsorption performance of AMTD-TCT. This mechanism enables efficient Hg(II) sequestration from aqueous environments.

Figure 16.

Schematic illustration of the Hg adsorption mechanism by AMTD-TCT.

3.5. Environmental Implications

Hg contamination remains a critical and persistent global environmental concern due to its extreme toxicity, long environmental residence time, and strong bioaccumulation potential. In real-world contexts, such as abandoned mining areas, industrial discharge zones, and agricultural lands near anthropogenic emission sources, Hg often occurs at elevated concentrations in both soil and water systems. Its most hazardous transformation pathway involves the microbial conversion of inorganic Hg(II) into methylmercury, a bioavailable and highly toxic form that readily biomagnifies through food chains, posing severe risks to ecosystems and human health [71].

Preventing Hg(II) migration or transformation into more toxic species is therefore essential for mitigating associated risks. In this regard, the AMTD-TCT material developed in this study exhibits outstanding Hg(II) adsorption performance. As summarized in Table 1, its maximum adsorption capacity far surpasses that of many conventional porous adsorbents [27,72,73,74,75]. This superior performance can be attributed to its multifunctional structure, featuring sulfur and nitrogen donor groups, hierarchical porosity, and a high surface area, which facilitates multiple concurrent adsorption mechanisms, such as S/N coordination, surface complexation, ion exchange, and electrostatic interactions.

Table 1.

Comparison of reported adsorption capacities of porous materials for Hg(II).

Given these characteristics, AMTD-TCT demonstrates considerable potential for application in diverse Hg-contaminated settings. For water remediation, practical deployment would likely involve shaping the powder into macroscopic granules for use in engineered flow-through systems. Key potential application scenarios include: (1) Packaged-Bed Columns: Granular AMTD-TCT could potentially be used in fixed-bed columns to treat industrial wastewater or contaminated groundwater, providing a high-contact system for Hg(II) removal. (2) Permeable Reactive Barriers (PRBs): For in situ groundwater remediation, the granular material shows potential for deployment as a permeable wall to intercept a Hg plume, an established technology for in situ remediation of contaminated aquifers [76]. However, it is crucial to emphasize that adsorption performance in well-mixed batch systems can differ significantly from that in continuous flow modes [77], such as in packed columns or PRBs. This is particularly true under dynamic field conditions where fluctuations in pH, ionic strength, and the presence of competing ions can profoundly impact adsorption efficiency and longevity, as evidenced in previous studies [78]. Therefore, while the exceptional batch performance is promising, it does not guarantee success in continuous flow systems. Dedicated column studies and pilot-scale testing under realistic chemical and hydraulic conditions are necessary to rigorously validate the efficacy of AMTD-TCT in such dynamic applications. In agricultural soils, it may be used as an amendment to immobilize Hg(II), thereby limiting plant uptake and protecting food safety, a strategy supported by previous studies using adsorbents for metal immobilization [79].

It is important to note that this study employed a single-metal system to benchmark the intrinsic affinity of AMTD-TCT for Hg(II). Natural environments often contain a cocktail of competing ions. Future research must therefore prioritize competitive adsorption experiments using multi-metal solutions and authentic Hg-contaminated soil/water samples to rigorously evaluate the selectivity and practical efficacy of AMTD-TCT.

These findings highlight the practical significance of AMTD-TCT in addressing Hg pollution under real-world conditions. It is important to note that the current work evaluates AMTD-TCT in its as-synthesized powder form, with SEM analysis indicating primary particle sizes in the micrometer range (approximately 1–20 μm, Figure 5). This small particle size contributes to the favorable adsorption kinetics, while the moderate BET surface area underscores the dominant role of chemisorption over physisorption in the high uptake capacity. While this morphology is ideal for maximizing specific surface area and achieving rapid kinetics in batch adsorption studies, it may pose practical challenges in continuous flow systems due to potential issues such as high pressure drop and column clogging. Therefore, for deployment in such practical scenarios (e.g., fixed-bed columns or permeable reactive barriers), future work will focus on post-synthetic shaping processes, such as granulation into macroscopic pellets or immobilization onto robust, porous substrates, which are common strategies to enhance hydraulic performance while retaining high adsorption capacity [80,81].

Regarding the practical management of spent adsorbent, two main pathways can be considered based on the strong binding affinity demonstrated by the minimal desorption in 0.01 M NaNO3: (1) Description and Potential Regeneration: The strong chemisorption between AMTD-TCT and Hg(II), while limiting desorption under mild conditions, suggests that more aggressive eluents would be required for regeneration and resource recovery. Concentrated acids (e.g., 2–4 M HCl or HNO3) or strong complexing agents (e.g., 0.1–0.5 M EDTA) could be explored in future studies to strip Hg(II) from the saturated polymer [57,82]. However, such harsh conditions may impact the polymer’s structural integrity and adsorption capacity over multiple cycles, requiring careful optimization. (2) Disposal and Utilization Alternatives: If regeneration proves economically unviable or technically challenging, the Hg-laden polymer must be managed as hazardous waste. Stabilization/solidification using cement-based matrices presents a well-established disposal route that effectively immobilizes heavy metals and prevents leaching [83]. Alternatively, given the exceptional stability of the AMTD-TCT-Hg complex demonstrated in our desorption studies, the spent material could potentially be repurposed in safe encapsulation applications, such as in construction materials where the encapsulated Hg would be physically isolated from the environment. However, such applications would require thorough evaluation of long-term leaching behavior under various environmental conditions.

From a scalability perspective, the use of readily available starting materials and the absence of rare metals or complex synthesis protocols enhance the economic viability of AMTD-TCT. Its high per-gram adsorption capacity means that smaller quantities are needed to achieve remediation targets, potentially reducing both production and operational costs. Nonetheless, to fully evaluate real-world applicability, further techno-economic assessments, including lifecycle cost analyses and pilot-scale field testing, are warranted. Furthermore, while this study established the remarkable intrinsic adsorption capacity of AMTD-TCT under optimized, high-concentration conditions, its performance in treating real environmental matrices with typically much lower Hg concentrations (µg L−1 to low mg L−1) and numerous competing ions requires dedicated investigation to accurately assess its practical remediation potential.

In conclusion, AMTD-TCT represents a significant advancement in Hg(II) remediation technology, combining high adsorption capacity, structural resilience, and environmental compatibility. By capturing Hg(II) prior to its conversion into mobile or bioavailable species, the material offers a promising pathway for mitigating Hg-related ecological and public health impacts. Future work should focus on optimizing its formulation for practical deployment (e.g., granulation), developing and optimizing regeneration protocols, validating long-term field performance in engineered systems like PRBs and columns, and integrating AMTD-TCT into comprehensive remediation frameworks, particularly those aligned with international efforts such as the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a rationally designed porous organic polymer, AMTD-TCT, constructed via nucleophilic substitution between thiol-rich AMTD and triazine-based TCT. The resulting mesoporous framework integrates dual nitrogen and sulfur coordination motifs, offering abundant high-affinity binding sites and excellent structural stability across a broad pH range.

AMTD-TCT exhibited an ultrahigh Hg(II) adsorption capacity of 1257.7 mg g−1 and a minimal desorption rate of 6.21%, outperforming conventional sorbents. Kinetic and isotherm analyses confirmed that Hg(II) sequestration is dominated by monolayer chemisorption, involving S-Hg and N-Hg coordination, Na+/Hg2+ ion exchange, and diffusion-facilitated capture through hierarchical pores.

These findings validate the effectiveness of combining multifunctional binding groups with hierarchical porosity to achieve superior adsorption performance. The molecular design strategy employed here provides a scalable and metal-free platform for the development of high-efficiency adsorbents, with broad potential for application in heavy metal remediation under environmentally relevant conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13113652/s1, Figure S1: Unprocessed FTIR spectra. Spectra of (a) AMTD, (b) TCT, (c) AMTD-TCT, and (d) AMTD-TCT-Hg. The inset in (c) shows a photograph of the AMTD-TCT powder. Figure S2: Distribution diagram of predominant Hg(II) species across the studied pH range. Figure S3: (a) Elemental composition of AMTD-TCT before Hg adsorption; (b) elemental composition of AMTD-TCT after Hg adsorption. Table S1: Experimental design for adsorption and desorption experiments. Table S2: Differences in Hg(II) concentrations in supernatants among treatments under the same pH conditions. Table S3: Significant differences within the same treatment group under different pH conditions. Table S4: Significant differences among different treatment groups at the same pH. Table S5: Significant differences within the same treatment group under different concentration conditions. Table S6: Significant differences among different treatment groups at the same concentration. Table S7: Significant differences within the same treatment group under different adsorbent dosage conditions. Table S8: Significant differences among different treatment groups at the same adsorbent dosage. Table S9: Significant differences among different treatment groups at the same time. Table S10: Significant differences within the same treatment group under different time conditions. Table S11: Fitting parameters of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models. Table S12: Fitting parameters of adsorption kinetics models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L. and R.S.; methodology, K.L. and R.S.; validation, K.L. and R.S.; formal analysis, K.L. and R.S.; investigation, K.L.; resources, R.S.; data curation, K.L.; writing-original draft preparation, K.L.; writing-review and editing, K.L. and R.S.; visualization, K.L.; supervision, R.S.; project administration, R.S.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province, grant number Qian ke he ping tai ren cai - YQK [2023] 027. The APC was funded by the same grant.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support from the instrument analysis platforms of Guizhou Normal University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raj, D.; Maiti, S.K. Sources, Toxicity, and Remediation of Mercury: An Essence Review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-S.; Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Rooney, D.W.; Chen, Z.; Rahim, N.S.; Sekar, M.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; et al. The Toxicity of Mercury and Its Chemical Compounds: Molecular Mechanisms and Environmental and Human Health Implications: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5100–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-R.; Johs, A.; Bi, L.; Lu, X.; Hu, H.-W.; Sun, D.; He, J.-Z.; Gu, B. Unraveling Microbial Communities Associated with Methylmercury Production in Paddy Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 13110–13118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrey, E.F.; Simmons, W. Mercury and Parkinson’s Disease: Promising Leads, but Research Is Needed. Park. Dis. 2023, 2023, 4709322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Bae, S.; Lim, H.; Lim, J.-A.; Lee, Y.-H.; Ha, M.; Kwon, H.-J. Mercury Exposure in Association with Decrease of Liver Function in Adults: A Longitudinal Study. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2017, 50, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castriotta, L.; Rosolen, V.; Biggeri, A.; Ronfani, L.; Catelan, D.; Mariuz, M.; Bin, M.; Brumatti, L.V.; Horvat, M.; Barbone, F. The Role of Mercury, Selenium and the Se-Hg Antagonism on Cognitive Neurodevelopment: A 40-Month Follow-Up of the Italian Mother-Child PHIME Cohort. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 230, 113604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Herz, K.T. Brain Development and Methylmercury: Underestimation of Neurotoxicity. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2011, 78, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, L.I.; Zelikoff, J.T. Toxicology and Immunotoxicology of Mercury: A Comparative Review in Fish and Humans. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2001, 4, 161–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelar, K.L.; Kidd, K.A.; Drevnick, P.E.; Munkittrick, K.R.; Burgess, N.M.; Roberts, A.P.; Smith, J.D. Evidence of Impaired Health in Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) from a Biological Mercury Hotspot in Northeastern North America, Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, K.L.; Trudeau, V.L. Mercury-Induced Reproductive Impairment in Fish, Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hou, D.; Cao, Y.; Ok, Y.S.; Tack, F.M.; Rinklebe, J.; O’Connor, D. Remediation of Mercury Contaminated Soil, Water, and Air: A Review of Emerging Materials and Innovative Technologies. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Da’aNa, D.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; Khraisheh, M. Adsorptive Removal of Mercury from Water by Adsorbents Derived from Date Pits. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Gao, J.; Pierce, E.; Strong, P.J.; Wang, H.; Liang, L. In Situ Remediation Technologies for Mercury-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 8124–8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atia, A.A.; Donia, A.M.; Elwakeel, K.Z. Selective Separation of Mercury (II) Using a Synthetic Resin Containing Amine and Mercaptan as Chelating Groups. React. Funct. Polym. 2005, 65, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtch, N.C.; Jasuja, H.; Walton, K.S. Water Stability and Adsorption in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10575–10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Xiao, K.; Duan, H.; Zhao, H. The Chemical Stability of Metal-Organic Frameworks in Water Treatments: Fundamentals, Effect of Water Matrix and Judging Methods. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Dai, S.; Zhao, C.; Ma, C.; Wei, L.; Zhu, M.; Chong, S.Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, L.; et al. Cooper, Reconstructed Covalent Organic Frameworks. Nature 2022, 604, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Jiang, D. Covalent Organic Frameworks for Heterogeneous Catalysis: Principle, Current Status, and Challenges. ACS Central Sci. 2020, 6, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Suarez, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J. Porous Organic Polymers as a Promising Platform for Efficient Capture of Heavy Metal Pollutants in Wastewater. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 4000–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajal, S.; Dutta, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Porous Organic Polymers (POPs) for Environmental Remediation. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 4083–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Lustig, W.P.; Bi, S.; Williams, L.J.; Hu, J.; Li, J. NanoPOP: Solution-Processable Fluorescent Porous Organic Polymer for Highly Sensitive, Selective, and Fast Naked Eye Detection of Mercury. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 27394–27401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, C.; Tang, J.; Luo, L.; Yu, G. Fluorescent Porous Organic Polymers. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 1168–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.; Pal, H. Recent Advances in Porous Organic Polymers (POPs): The Emerging Sorbent Materials with Promises Towards Toxic and Radionuclides Metal Ions Separations. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velempini, T.; Pillay, K. Sulphur Functionalized Materials for Hg (II) Adsorption: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, D.; Kuang, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.-N. Postfunctionalization of Porous Organic Polymers Based on Friedel–Crafts Acylation for CO2 and Hg2+ Capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36652–36659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Lu, P.; Wang, Q.; He, C. Thiol-/Thioether-Functionalized Porous Organic Polymers for Simultaneous Removal of Mercury (II) Ion and Aromatic Pollutants in Water. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 7683–7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Yan, W.; Chen, T.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.-N. N-Rich Porous Organic Polymers Based on Schiff Base Reaction for CO2 Capture and Mercury (II) Adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 587, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyllberg, U.; Bloom, P.R.; Qian, J.; Lin, C.-M.; Bleam, W.F. Complexation of mercury (II) in soil organic matter: EXAFS evidence for linear two-coordination with reduced sulfur groups. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 4174–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.A.; Roy, B.; Mandal, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S. A Kamikaze Approach for Capturing Hg2+ Ions through the Formation of a One-Dimensional Metal–Organometallic Polymer. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner-Döbler, I.; von Canstein, H.; Li, Y.; Timmis, K.N.; Deckwer, W.-D. Removal of mercury from chemical wastewater by microorganisms in technical scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 4628–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.E.; Theodorakos, P.M.; Fey, D.L.; Krabbenhoft, D.P. Mercury concentrations and distribution in soil, water, mine waste leachates, and air in and around mercury mines in the Big Bend region, Texas, USA. Environ. Geochem. Health 2015, 37, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reash, R.J. Bioavailability of mercury in power plant wastewater and ambient river samples: Evidence that the regulation of total mercury is not appropriate. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2019, 15, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Qu, Z.; Huang, W.; Mei, J.; Chen, W.; Zhao, S.; Yan, N. Regenerable Ag/graphene sorbent for elemental mercury capture at ambient temperature. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2015, 476, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U., Jr. Activated carbons and low cost adsorbents for remediation of tri- and hexavalent chromium from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 762–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.; Croft, R.; Flint, L.; Arias-Paić, M. Stannous Chloride Reduction–Filtration for Hexavalent and Total Chromium Removal from Groundwater. AWWA Water Sci. 2020, 2, e1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Study on the Simultaneous Reduction of Methylmercury by SnCl2 when Analyzing Inorganic Hg in Aqueous Samples. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 68, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algieri, V.; Tursi, A.; Costanzo, P.; Maiuolo, L.; De Nino, A.; Nucera, A.; Castriota, M.; De Luca, O.; Papagno, M.; Caruso, T.; et al. Thiol-Functionalized Cellulose for Mercury Polluted Water Remediation: Synthesis and Study of the Adsorption Properties. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surfaces of Glass, Mica and Platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Gao, Y.; Tan, X.; Chen, C. Polyaniline-Modified Mg/Al Layered Double Hydroxide Composites and Their Application in Efficient Removal of Cr(VI). ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4361–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the Modeling of Adsorption Isotherm Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Chen, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Magnetic COFs for the Adsorptive Removal of Diclofenac and Sulfamethazine from Aqueous Solution: Adsorption Kinetics, Isotherms Study and DFT Calculation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.H.; Hashim, M.A.; Hayder, G.; Bollinger, J.-C. Comparative Evaluation of the Dubinin–Radushkevich Isotherm and Its Variants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 15002–15011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, N.D.; Yang, R.T. Theoretical Basis for the Dubinin-Radushkevitch (DR) Adsorption Isotherm Equation. Adsorption 1997, 3, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. The Kinetics of Sorption of Basic Dyes from Aqueous Solution by Sphagnum Moss Peat. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1998, 76, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethiya, A.; Jangid, D.K.; Pradhan, J.; Agarwal, S. Role of Cyanuric Chloride in Organic Synthesis: A Concise Overview. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2023, 60, 1495–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; Figg, C.A.; Swartz, J.L.; Brooks, W.L.A.; Sumerlin, B.S. Multifunctional Homopolymers: Postpolymerization Modification via Sequential Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]