Process Design and Simulation of Biodimethyl Ether (Bio-DME) Production from Biomethane Derived from Agave sisalana Residues

Abstract

1. Introduction

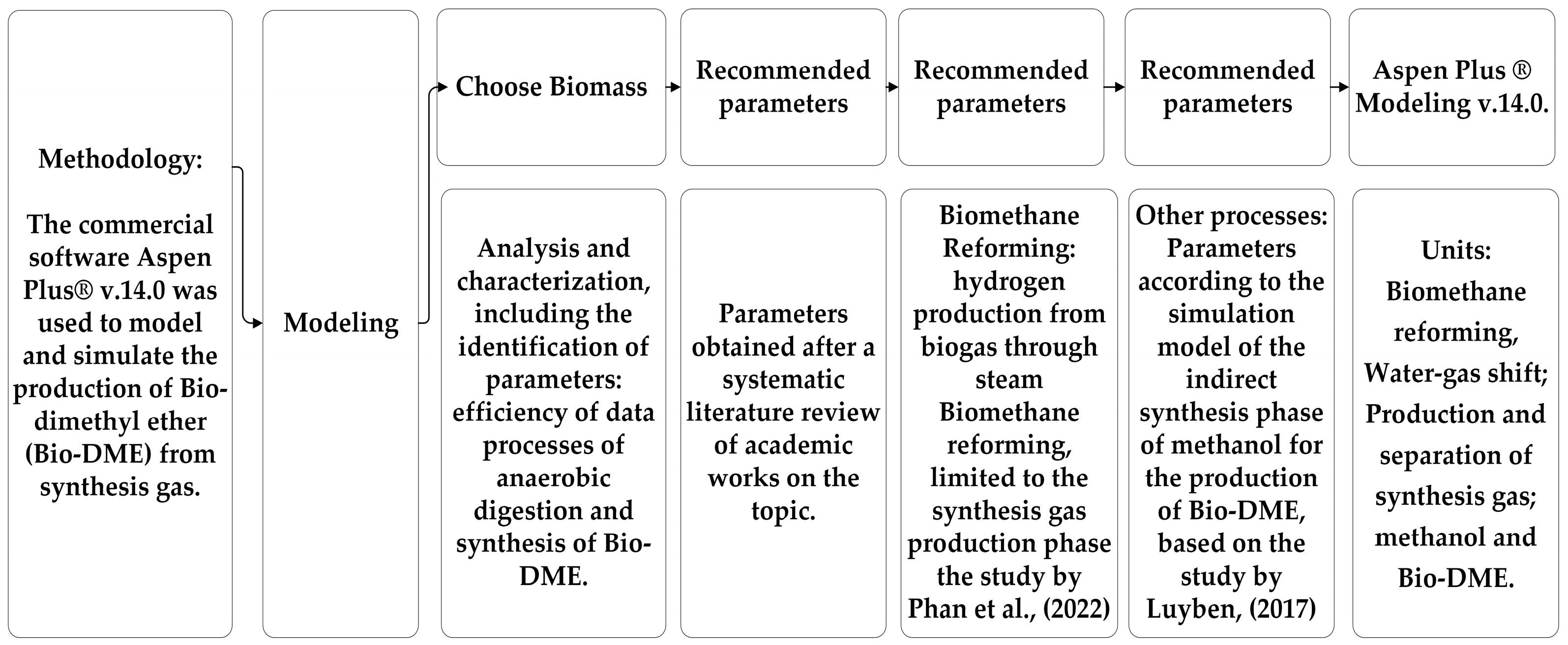

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

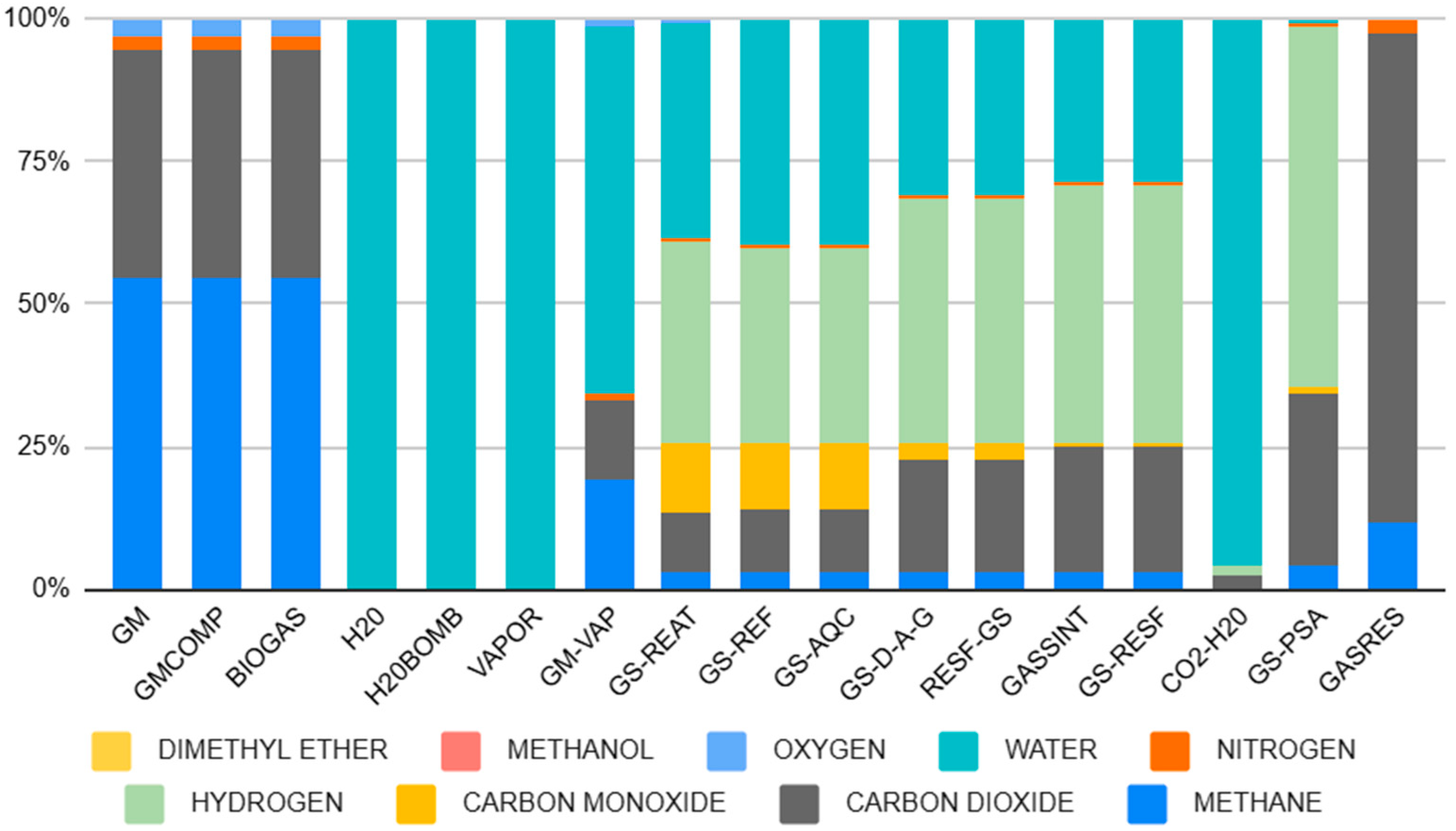

- Steam reforming of biogas and water-gas shift to form a gaseous mixture (synthesis gas) [1,5,6], composed mainly of hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrogen (N2) in proportions that vary depending on the operating conditions and the type of biomass used [7,22]. The input data were carefully selected to reflect the actual operating conditions and characteristics of Agave sisalana biomass. The composition of the biogas, which serves as raw material for steam reforming, was obtained from studies of anaerobic digestion of Agave sisalana, with a gross biomethane yield of 54 NmL/L·d, as presented by Soares [8]. Figure 1 below shows the initial steps of the simulation.

- (ii)

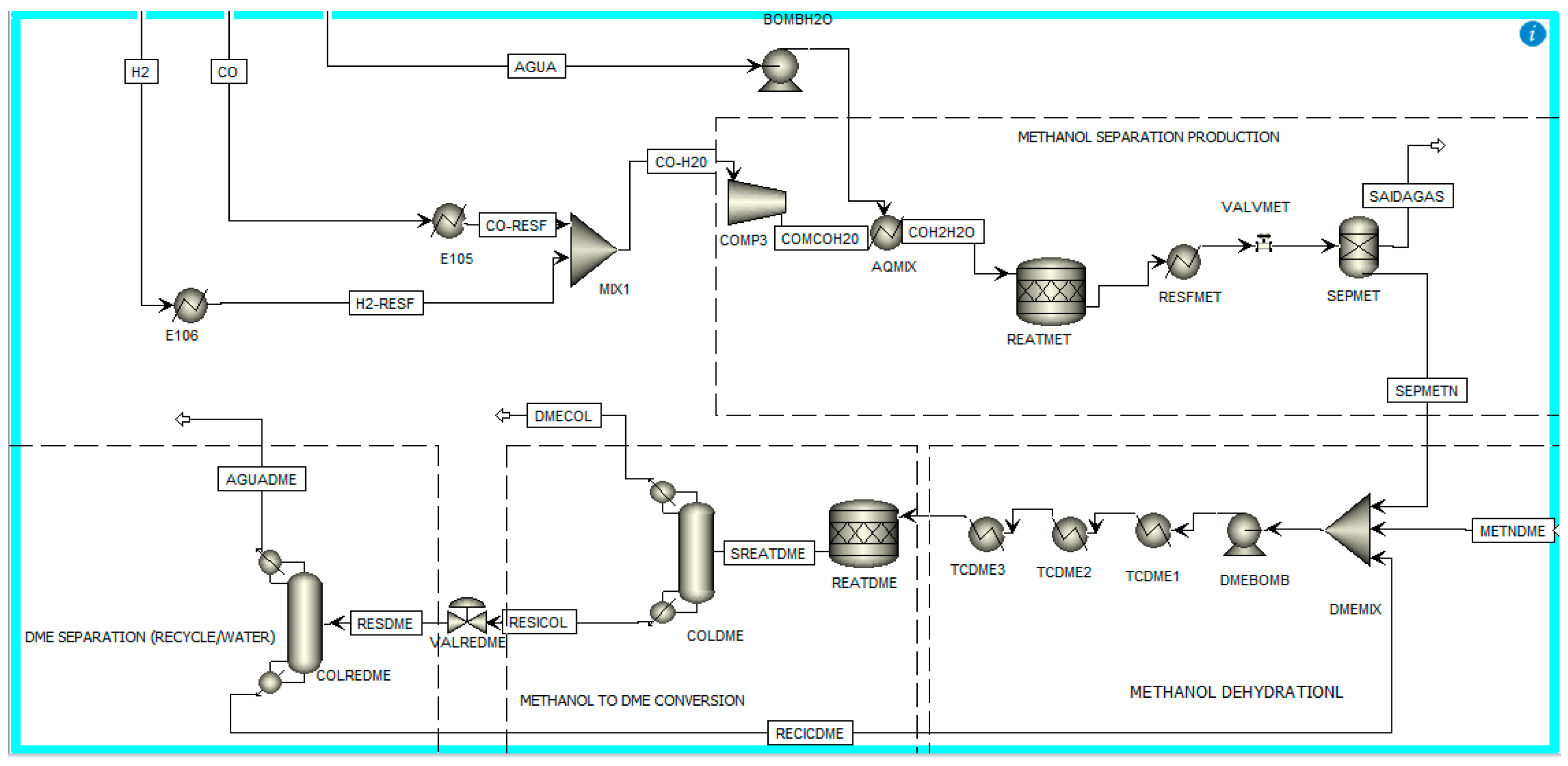

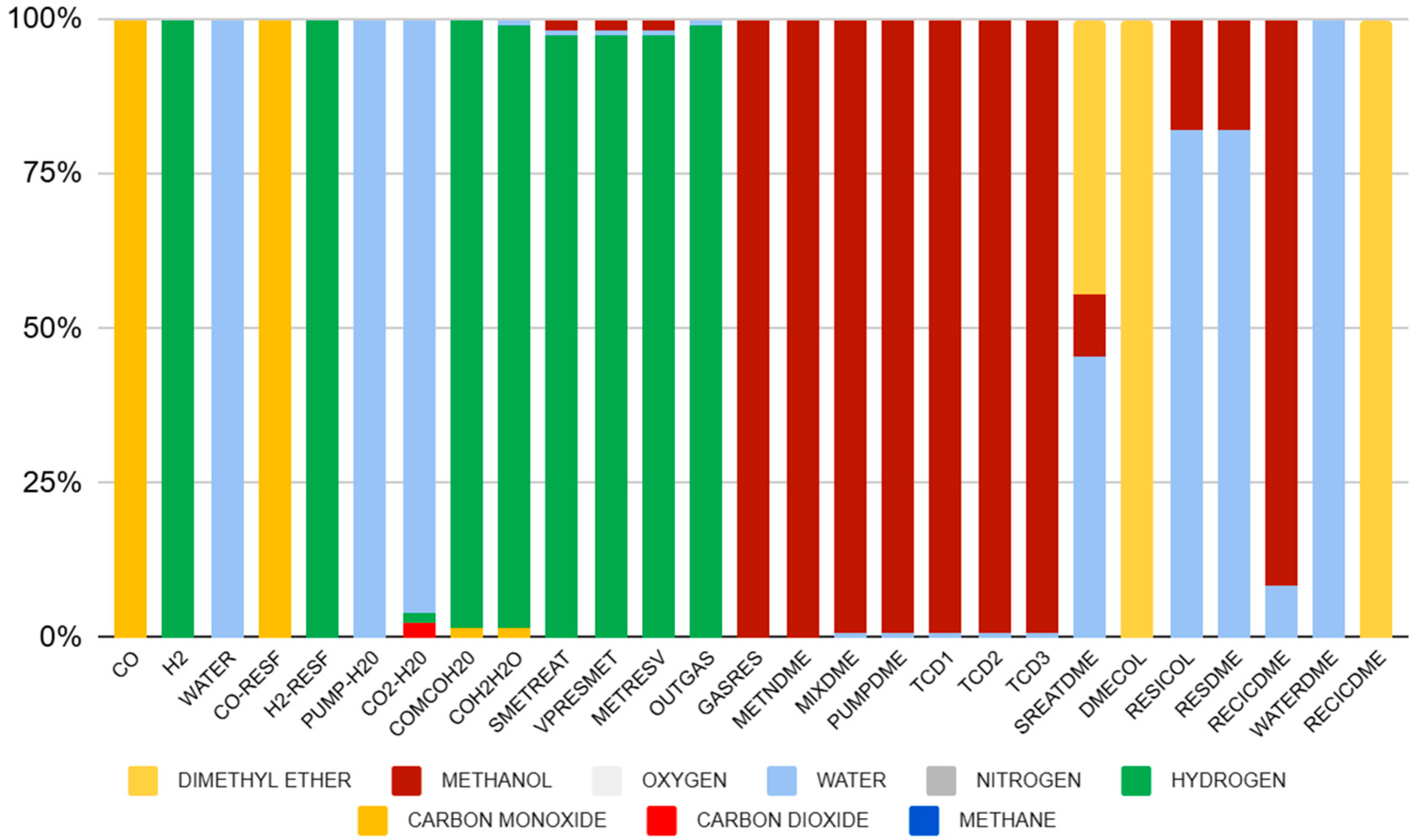

- Indirect methanol synthesis followed by methanol dehydration, including separation and recycling for Bio-DME production. In this stage, Bio-DME production initially involves obtaining synthesis gas derived from anaerobic digestion [7]. This gas undergoes cleaning and conditioning processes, followed by methanol synthesis and, finally, methanol dehydration to form Bio-DME [6,7,20]. The LPMEOHTM (Liquid Phase Methanol) process is a promising technology for the sintering of methanol from synthesis gas, presenting better results [1,5,20]. Figure 2 below shows the simulation of the stage (ii):

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Results of Step (i) Steam Reforming of Biogas and Water-Gas Shift for Synthesis Gas Formation

3.1.1. Analysis of Conditions Step (i) Methane Reform

Analysis of the Indicators Step (i)

- Methane Conversion (XCH4):

- Ratio H2/CO in syngas (GS-REAT)

- Reactor Operating Condition:

- -

- H2O: 2.5284 kmol/h

- -

- CH4: 0.7526 kmol/h

3.1.2. Simulation Results of Step (ii), Indirect Synthesis of Methanol, Dehydration for Bio-DME Production

Analysis of the Indicators Step (ii)

- CO conversion, we identified:

- Methanol Reactor Dehydration Conversion:

- Bio-DME Yield from Methanol:

- Bio-DME Conversion of Synthesis Reactor

3.2. Simulation Results of the Stage (ii) Comparison with Data from the Literature

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMBRAPA | Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation |

| LGP | Liquefied Petroleum |

| LPMEOHTM | Liquid Phase Methanol |

| UFBA | Federal University of Bahia |

| UFRB | Federal University of the Recôncavo of Bahia |

| WGS | Water-Gas Shift |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Equipment | |||

| Heat Exchangers | (E-100, E-101, E-102, E-103) | ||

| Water-Gas Displacement Reactors | (HT-WGS, LT-WGS) | ||

| Flash Tab | (FLASH) | ||

| Compressor | (COMP) | ||

| Parameters | |||

| Temperature | Pressure | Molar Flow Rates | |

| Biogas inlet | 909 °C | 16.32 kg/cm2 | 1 kmol/h |

| Input of the reformer | 908.7 °C | 16.32 kg/cm2 | 4 kmol/h |

| Exit of the reformer | 909 °C | 16.32 kg/cm2 | 5 kmol/h |

| Water-Gas Displacement Reactor (HT-WGS) | 350 °C | 16.32 kg/cm2 | 5 kmol/h |

| Water-Gas Displacement Reactor (LT-WGS) | 210 °C | 16.32 kg/cm2 | 5 kmol/h |

| Flash Separator | 38 °C | 15.70 kg/cm2 | 4 kmol/h |

Appendix A.2

| Methanol Production Phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment | |||

| Mixer | (MIX1) | ||

| Compressor | (COMP3) | ||

| Water Pump | (BOMBH2O) | ||

| Methanol reactor | (REATMET) | ||

| Heat exchanger | (AQMIX, RESFMET) | ||

| Methanol Valve | (VALVMET) | ||

| Methanol Separator | (SEPMET) | ||

| Parameters | |||

| Phase | Temperature | Pressure | Molar Flow Rates |

| Methanol reactor inlet | 250 °C | 50 kg/cm2 | 2 kmol/h |

| Methanol reactor output | 250 °C | 51 kg/cm2 | 2 kmol/h |

| Methanol Separator Inlet | 57 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 2 kmol/h |

| Methanol Separator | 25 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 2 kmol/h |

| Methanol dehydration phase | |||

| Equipment | |||

| Mixer | (DMEMIX) | ||

| Bomb | (DMEBOMB) | ||

| Heat exchanger | (TCDME1, TCDME2, TCDME3) | ||

| Parameters | |||

| Phase | Temperature | Pressure | Molar Flow Rates |

| Mixer Inlet | 25 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 555 kmol/h |

| Mixer Inlet (Recycle) | 66 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 67 kmol/h |

| Mixer Outlet | 29 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 622 kmol/h |

| Inlet Heat Exchanger | 30 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 622 kmol/h |

| Outlet Heat Exchanger | 250 °C | 10 kg/cm2 | 622 kmol/h |

| Bio-DME Conversion and Separation | |||

| Equipment | |||

| Bio-DME Reactor | (REATDME) | ||

| Bio-DME Separator | (SEPMETN) | ||

| Bio-DME Column | (COLDME) | ||

| Methanol Valve | (VALVMET) | ||

| Bio-DME Column | (COLREDME) | ||

| Parameters | |||

| Phase | Temperature | Pressure | Molar Flow Rates |

| Bio-DME Reactor Inlet | 250 °C | 10 kg/cm2 | 622 kmol/h |

| Reactor Output Bio-DME | 350 °C | 10 kg/cm2 | 622 kmol/h |

| Column Bio-DME 1 | 350 °C | 10 kg/cm2 | 622 kmol/h |

| Column Bio-DME 2 | 87 °C | 1 kg/cm2 | 345 kmol/h |

References

- Eichler, P.; Santos, F.; Toledo, M.; Zerbin, P.; Schmitz, G.; Alves, C.; Ries, L.; Gomes, F. Production of biometanol via lignocellulosic biomass gasification. Química Nova 2015, 38, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P. Fossil Fuels. 2017. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Ma, L.; Ding, M.; Zhang, X.; Yin, X. Demonstration of pilot-scale bio-dimethyl ether synthesis via oxygen- and steam-enriched gasification of wood chips. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, Z.; Rezaeimanesh, M.; Tohidian, T.; Rahimpour, M.R. Dimethyl ether: A review of technologies and production challenges. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2014, 82, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Moreno, F.M.; Gonzalez-Castaño, M.; Arellano-García, H.; Reina, T.R. Exploring profitability of bioeconomy paths: Dimethyl ether from biogas as case study. Energy 2021, 225, 120–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedeli, M.; Negri, F.; Manenti, F. Biogas to advanced biofuels: Tech-no-economic analysis of one-step dimethyl ether synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.; Catizzone, E. Modelling and environmental aspects of direct or indirect dimethyl ether synthesis using digestate as feedstock. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2021, 8, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.L.; Faber, M.d.O.; Monteiro, A.F.; Cammarota, M.C.; Ferreira-Leitão, V.S. Potential use of sisal juice as raw material for sequential biological production of hydrogen and methane. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, M.S.; Adarme, O.F.H.; Volpi, M.P.C.; Flores-Rodriguez, C.I.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Mockaitis, G.; Pereira, G.A. Unveiling the biogas potential of raw Agave leaf juice: Exploring a novel biomass source. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sosa, L.B.; Santibáñez-Rocha, G.A.; Morales-Máximo, M.; González-Carabes, R.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Bustamante, C.A.G.; Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Ramos, I.S.; Reyes, C.I.V.; del Carmen Rodríguez Magallón, M.; et al. Evaluation of the energy potential of agro-industrial waste. Virtual J. Chem. 2021, 14, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, F.; de Paula, M.; Volpi, M.P.; Adarme, O.F.H.; Ribas, T.; da Silva, J.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Pereira, G.; Mockaitis, G. Transforming Semi-Arid Waste into High-Yield Biogas: An Approach to Sustainable Energy. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5049618 (accessed on 19 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.; Catizzone, E.; Freda, C. Process Simulation and Environmental Aspects of Dimethyl Ether Production from Digestate-Derived Syngas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrahman, A. Simulation and optimization of dimethyl ether (DME) synthesis processes using highly contaminated natural gas as feedstock. Processes 2025, 13, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA-AMF. DME from Biomass. Annex Reports. 2014. Available online: https://iea-amf.org/app/webroot/files/file/Annex%20Reports/AMF_Annex_14_dme_bio.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Styring, P.; Sanderson, P.W.; Gell, I.; Skorikova, G.; Sánchez-Martínez, C.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Sluijter, S.N. Carbon footprint of Power-to-X derived dimethyl ether using the sorption enhanced DME synthesis process. Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 1057190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, A.M.; Mujtaba, I.M.; Hall, P.; Lester, E.H.; Wu, T. Synthesis of bio-dimethyl ether based on carbon dioxide-enhanced gasification of biomass: Process simulation using Aspen Plus. Energy Technol. 2016, 4, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.S.; Minh, D.P.; Espitalier, F.; Nzihou, A.; Grouset, D. Hydrogen production from biogas: Process optimization using Aspen Plus®. Int. J. Hydrog Energy 2022, 47, 42027–42039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyben, W.L. Design and Control of a Conventional Process for the Production of Dimethyl Ether. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 4448–4459. [Google Scholar]

- de Melo, L.R.; Filho, R.M.; Efren, J.; Figueroa, J. Obtaining Dimethyl from Methanol: Simulation and Analysis of Product Processes; Associação Brasileira de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Petróleo e Gás: Natal, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, A.; Shah, N. Process exploration and assessment for the production of methanol and dimethyl ether from carbon dioxide and water. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 1541–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspen Plus TM. Aspen Engineering Suite; Aspen Technology Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; Available online: http://www.aspentech.com (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- EMBRAPA. Biogas and Its Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals. 2022. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1149613/1/DOC-49-final-1.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Peral, E.; Martín, M. Optimal Production of Dimethyl Ether from Switchgrass-Based Syngas via Direct Synthesis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 7465–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Chen, H.; Ding, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Dai, Z. Process simulation of single-step dimethyl ether production via biomass gasification. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phase | Temperature | Pressure |

|---|---|---|

| Reform | 909 °C | 16.32 kg/cm2 |

| Bio-DME overview | 250 °C | 50–51 kg/cm2 |

| Separation | 43.8–160.4 °C | 1.03–10 kg/cm2 |

| Products | Phase | Simulated Conversion (% Molar) | Literature Conversion (% Molar) | Difference Conversion | Simulated Yield/Selectivity (% Molar) | Literature Yield/Selectivity (% Molar) | Difference Yield/Selectivity | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Ether | Bio-DME Reactor Output | 44.59 | 49.90 | 5.31 | 99.00 | 99.79 | 0.79 | [19] |

| Methanol | Bio-DME Reactor Output | 8.89 | 1.50 | 7.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [19] |

| Water | Bio-DME Reactor Output | 45.50 | 48.60 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [19] |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Temperature | 909 °C |

| Pressure | 16.32 kgf/cm2 (~16 bar) |

| CH4 Conversion | 80.0% |

| H2/CO | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, R.d.J.; Alves, C.T.; Vitor, A.B.; Torres, E.A.; Torres, F.A. Process Design and Simulation of Biodimethyl Ether (Bio-DME) Production from Biomethane Derived from Agave sisalana Residues. Processes 2025, 13, 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113451

Rodrigues RdJ, Alves CT, Vitor AB, Torres EA, Torres FA. Process Design and Simulation of Biodimethyl Ether (Bio-DME) Production from Biomethane Derived from Agave sisalana Residues. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113451

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Rozenilton de J., Carine T. Alves, Alison B. Vitor, Ednildo Andrade Torres, and Felipe A. Torres. 2025. "Process Design and Simulation of Biodimethyl Ether (Bio-DME) Production from Biomethane Derived from Agave sisalana Residues" Processes 13, no. 11: 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113451

APA StyleRodrigues, R. d. J., Alves, C. T., Vitor, A. B., Torres, E. A., & Torres, F. A. (2025). Process Design and Simulation of Biodimethyl Ether (Bio-DME) Production from Biomethane Derived from Agave sisalana Residues. Processes, 13(11), 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113451