Decarbonizing Arctic Mining Operations with Wind-Hydrogen Systems: Case Study of Raglan Mine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

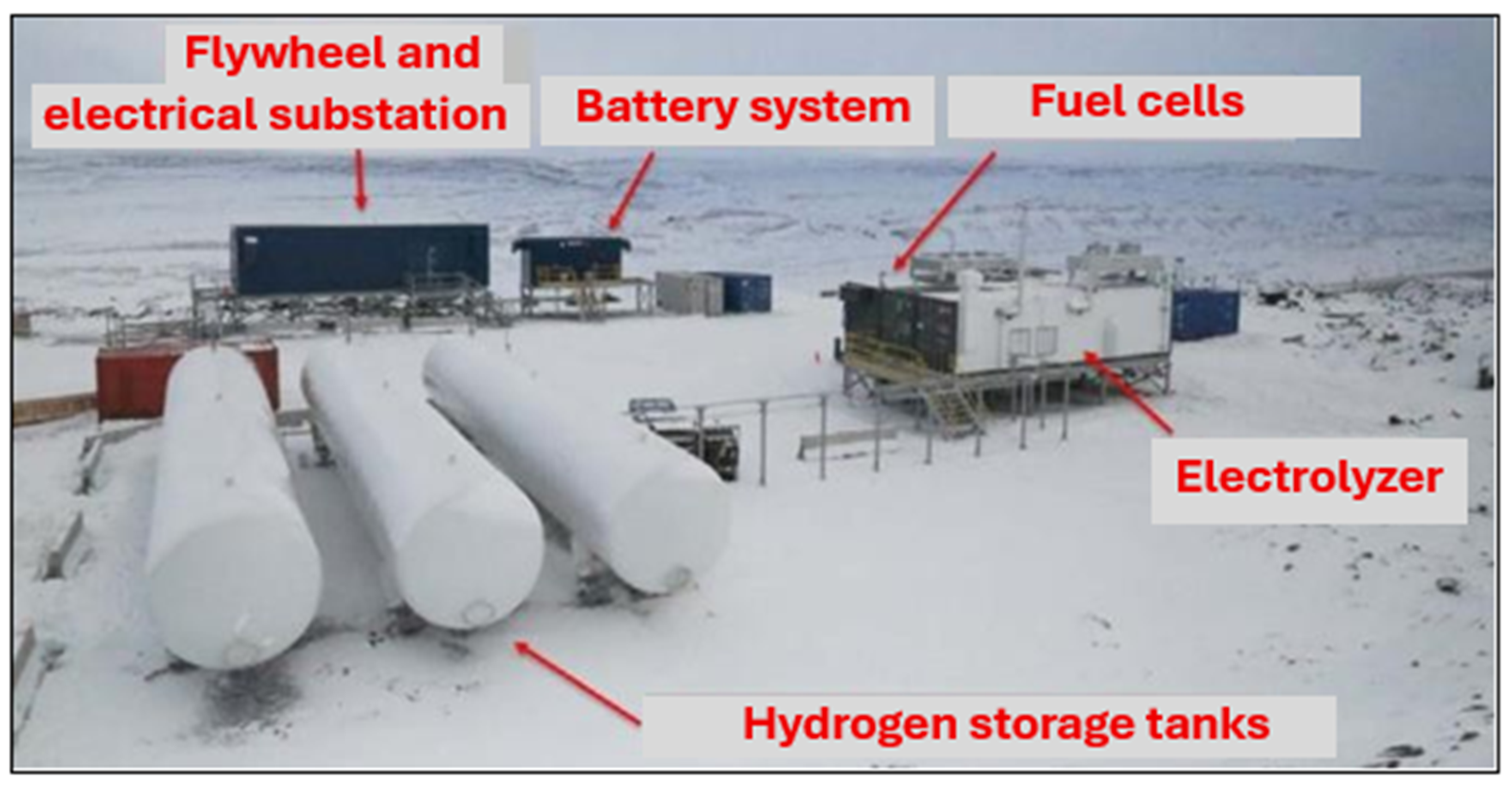

2.1. Brief Description of the Raglan Mine Energy Network

2.2. Conditions and Limitations of the Scope of the Study

2.3. Different Technical and Economic Decarbonization Scenarios

- Decarbonization of the 25 kV electrical network without decarbonizing the heat (heating and drying processes), which involves maintaining sufficient EMD diesel generators in operation to cogenerate all the heat required at the Raglan Mine.

- Decarbonization of the 25 kV electrical network, including heating, without decarbonizing the drying process. This scenario involves decarbonizing the majority of the 25 kV electrical network, while ensuring sufficient EMD to continue providing heat for the ore drying process.

- Decarbonization of the 25 kV electrical network, including heating and ore drying, involves decarbonizing the electricity and heat used by Mine Raglan.

- Decarbonization of vehicles and equipment involves the reduction of carbon emissions from these sources.

- Decarbonization of heavy transport focuses on the decarbonization of Raglan Mine’s heavy transport, i.e., all its mining trucks.

- Total decarbonization of Raglan Mine, which involves a comprehensive study of the entire Mine’s decarbonization, regrouping scenarios 3, 4, and 5.

2.4. Choice of Computer Model

2.5. Presentation of the System Studied

- Wind Turbine Technical and Financial Characteristics (based on real historical data at Raglan mine)

- Diesel Generators Technical and Financial Characteristics

- Battery Technical and Financial Characteristics

- Electrolyzer Technical and Financial Characteristics

- Hydrogen Tank Technical and Financial Characteristics

- PEMFC Technical and Financial Characteristics

2.6. Mathematical Model

2.7. Brief Analysis of Network Control and Stability

3. Model Validation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Data and Assumptions of the Model

- System CAPEX (2020): 700–1400 $/kW, reflecting costs of small- to medium-scale demonstration projects and the immaturity of supply chains.

- System CAPEX (2050): projected to fall below 200 $/kW, according to international roadmaps (IEA, Hydrogen Council, DOE targets), driven by scale effects, standardization, and improved stack durability.

- OPEX: expected to decrease proportionally with CAPEX, although maintenance of membranes and balance-of-plant will remain significant.

- Lifetime: expected to increase from ~20,000–30,000 h today to >60,000 h in the long term, reducing replacement frequency and lifecycle costs.

- System CAPEX (2020): 1000–1200 $/kW, depending on scale and region.

- System CAPEX (2050): projected to decrease to 200–500 $/kW, following learning curves similar to those of renewable technologies (solar PV, wind).

- Efficiency: expected to rise from 60 to 65% today to >75% by 2050, further improving hydrogen production costs.

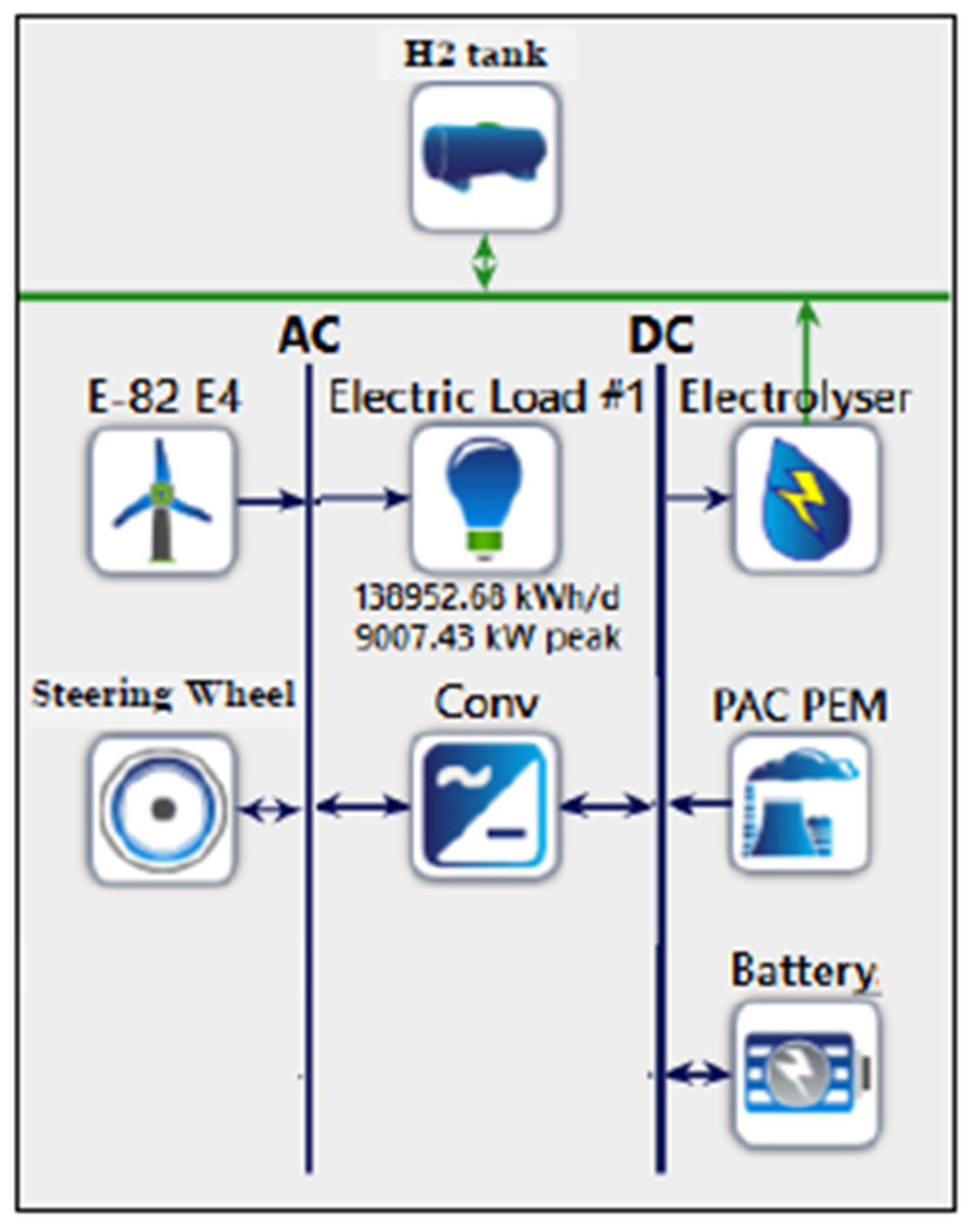

4.2. Model Results for Scenario 1, the Decarbonization of the 25 kV Electric Grid Without Heat

4.2.1. Case 1—Constant Operation of Four EMDs

4.2.2. Case 2—Optimized Operation of EMDs

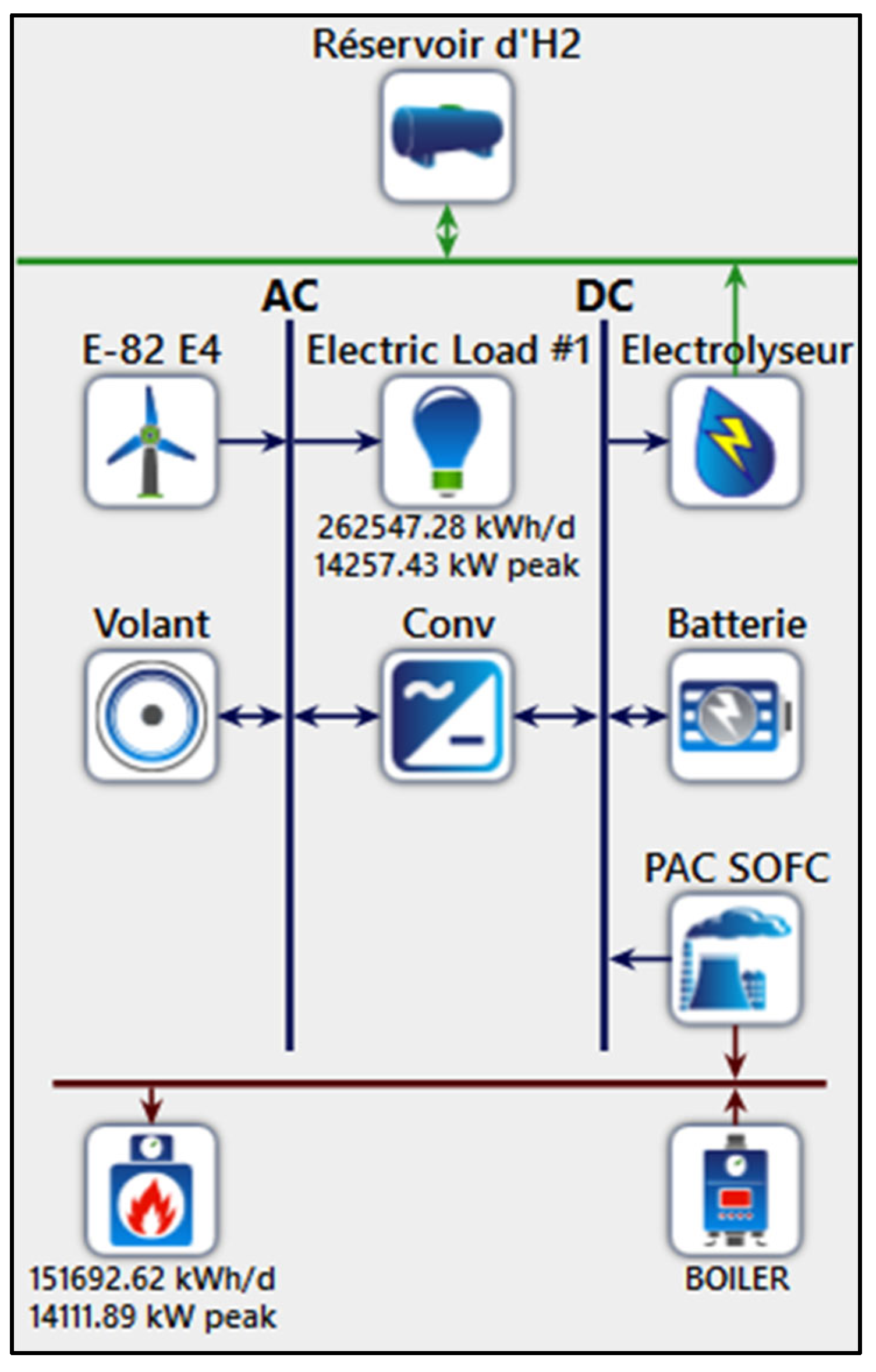

4.3. Model Results for Scenario 2, the Decarbonization of the 25 kV Electric Grid with Glycol Heating and Without Ore Drying

- Case 1: Use of PEMFC, with thermal demand aggregated into the electrical load under the assumption that 1 kWh of electricity can substitute 1 kWh of heat.

- Case 2: Use of Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) fuel cells with cogeneration, separating electricity and heat production, and supplemented by diesel boilers where necessary.

4.3.1. Case 1: Use of PEMFCs

4.3.2. Case 2: SOFC with Cogeneration

4.4. Model Results for Scenario 3, Full Decarbonization of the 25 kV Electricity and Heat Networks

- Case 1: PEMFC (no cogeneration): Since PEMFCs only produce electricity, the electrical and thermal loads are combined into a single demand profile. The assumption is made that 1 kWh of electricity can offset 1 kWh of heat demand.

- Case 2: SOFC (with cogeneration): SOFCs can produce both electricity and heat simultaneously. In this case, the electrical and thermal demands are modeled separately, with diesel boilers supplementing heat production when renewable generation is insufficient.

4.4.1. Case 1: Use of PEMFCs

4.4.2. Case 2: SOFCs with Cogeneration

4.5. Model Results for Scenario 4, Decarbonization of Mining Vehicles and Equipment

4.6. Model Results for Scenario 5, Decarbonization of Heavy Transport

4.7. Model Results for Scenario 6, Total Decarbonization of Raglan Mine

5. Discussion

5.1. Energy Comparison of Different Scenarios

- The mine can theoretically be supplied entirely by renewable energy, provided that heating processes are electrified.

- The integration of SOFCs in cogeneration partially addresses thermal needs but still requires complementary heating.

- The addition of a TCC significantly improves the integration of renewable heat, in some cases, almost doubling the share of renewable heat.

- Excess electricity, ranging from 20% to 30% in several scenarios, should not be considered wasted. As demonstrated in Scenario 2 with TCC integration, redirecting this surplus into thermal loads can increase renewable heat penetration by nearly 40%. Other potential pathways for valorization include charging of electric auxiliary vehicles and future hydrogen-based exports (e.g., ammonia), although these remain at a conceptual stage in the Arctic context.

5.2. Environmental and Economic Comparisons

- Scenarios utilizing PEM technologies generally enable higher decarbonization levels, albeit at higher costs.

- Scenarios with SOFC technologies offer better efficiency in terms of CAPEX, but renewable heat penetration remains more limited.

- Ambitious projects such as Scenario 6, Case 1 (total decarbonization with PEM), achieve the complete replacement of diesel but require nearly $1 billion in investment.

- The valorization of surplus electricity has a decisive influence on project viability. While unutilized energy reduces system efficiency and increases LCOE, strategies such as TCC integration improve economic outcomes by lowering diesel consumption. Although hydrogen export and ammonia production are not modeled in detail here, they represent longer-term opportunities to monetize excess electricity in Arctic mining operations.

- Discount and inflation rates are uncertain. In the simulations, the discount rate was set at 8% and inflation at 2%.

- Diesel price volatility plays a significant role. While current market conditions do not suggest significant long-term price decreases, the assumed values have a strong impact on NPVs.

- CO2 Emission Reduction Potential

- Qualitative Multi-Criteria Assessment

- Technical feasibility—reliability under Arctic conditions, proven integration.

- Environmental performance—diesel reduction and avoided CO2.

- Economic viability—CAPEX, ROI, NPV.

- System flexibility—capacity to valorize excess electricity and scale to transport/heating.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

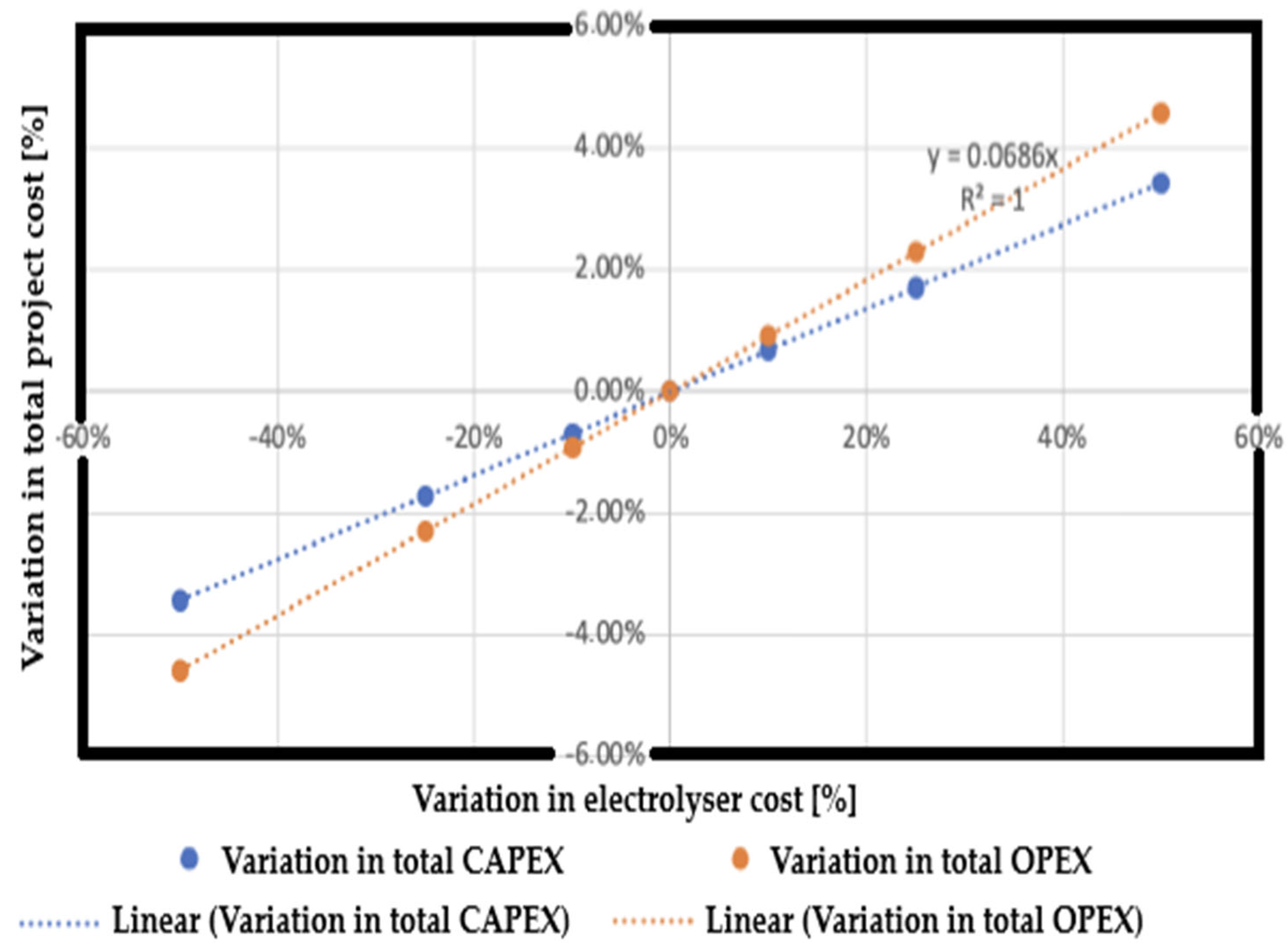

5.3.1. Electrolyzer

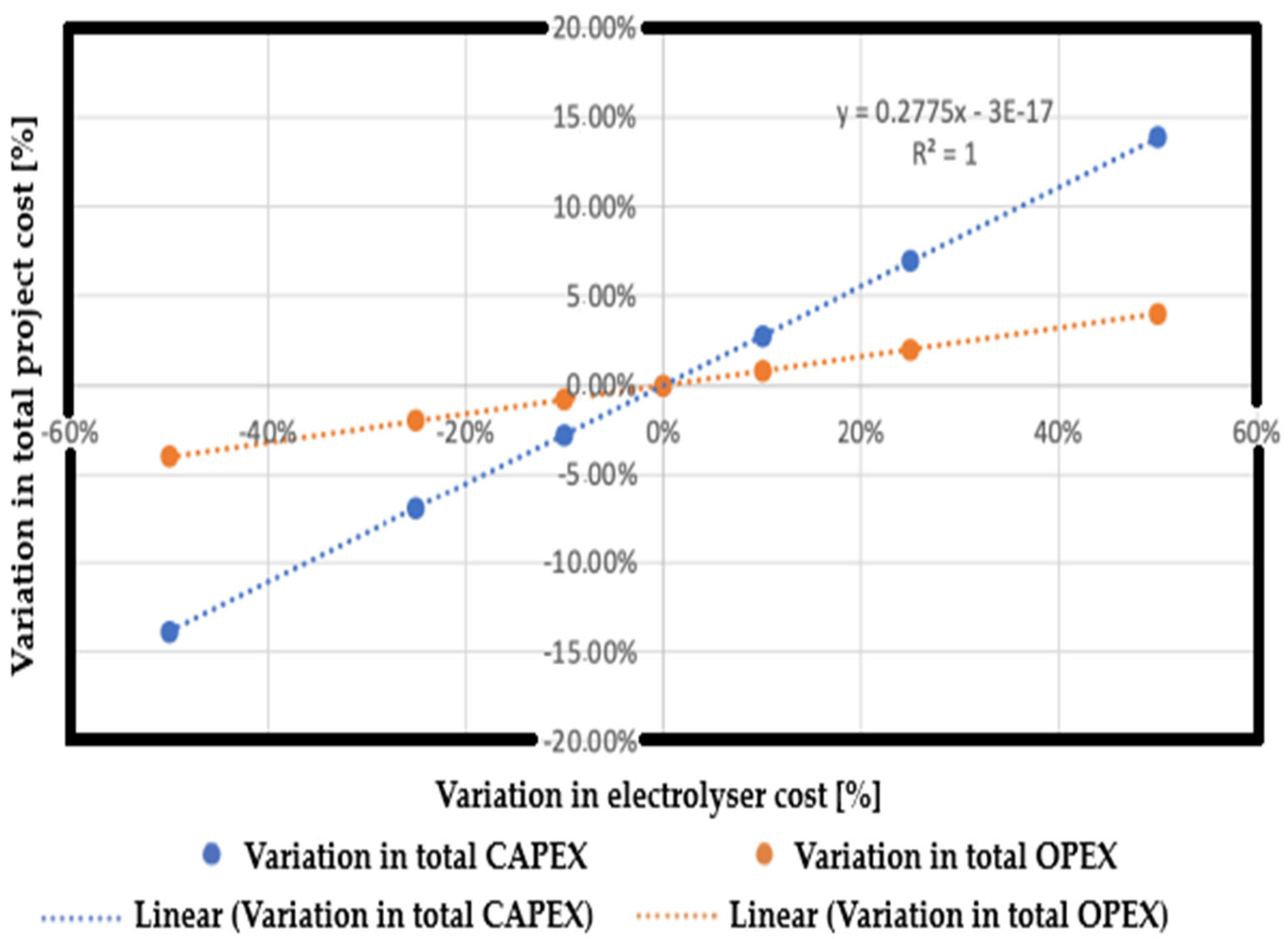

5.3.2. Hydrogen Storage

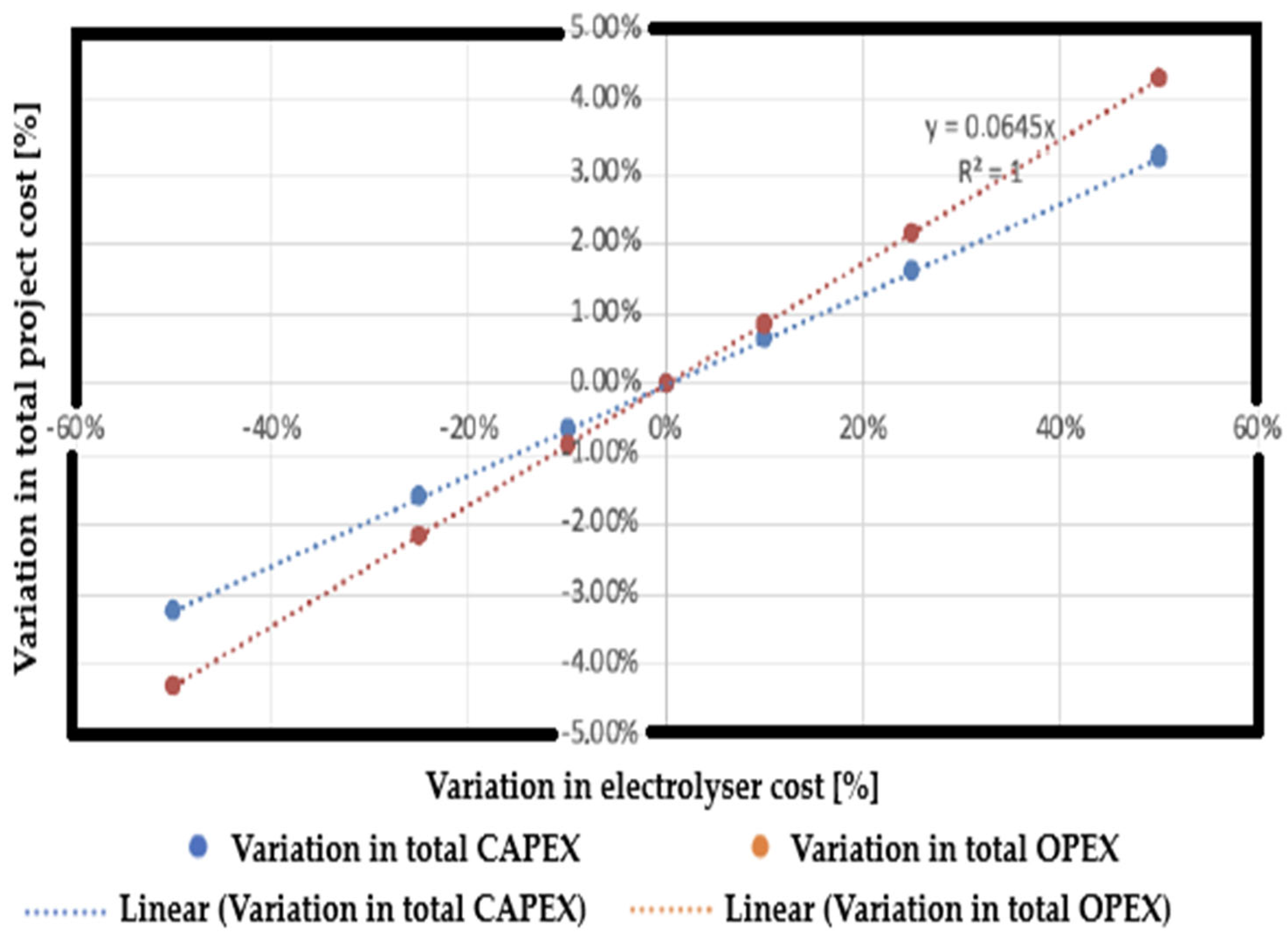

5.3.3. Fuel Cells

5.4. Challenges of Exploiting Renewable Energy in the Arctic

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditure |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DGUs | Diesel Generator Units |

| DOE | U.S. Department of Energy |

| EMD | Electro-Motive Diesel (type of generator used at Raglan) |

| FC | Fuel Cell |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| Gt | Gigatonne |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| HOMER | Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewables (software) |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost of Hydrogen |

| LCOS | Levelized Cost of Storage |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| ML | Million Liters |

| MW | Megawatt |

| MWh | Megawatt-hour |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| O&M | Operations and Maintenance |

| OPEX | Operating Expenditure |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PEMFC | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell |

| PHSS | Pumped Hydro Storage System |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| SOFC | Solid Oxide Fuel Cell |

| TCC | Thermal Charge Controller |

| tCO2eq | Tons of CO2 Equivalent |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

Appendix A

| Equation | Variable | Observation | Definition of Terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCOE | Equation taken from the IRENA [56] report “Renewable power generation costs 2021” | | |

Where | LCOS | The LCOS equation is taken from the work of Schmidt et al. [57]. | cost of electricity (or more broadly of energy) needed to power the system. either the dismantling cost or the value of the installation at the end of the system’s life (salvage value) annual amount of electricity discharged by the system |

| Amount of heat | The specific heat capacity of the exhaust gases is taken as 1066 J·kg−1·K−1 | mass of exhaust gases : The specific heat capacity of the exhaust gases Temperature variation | |

| OPEX | LCOE corresponds to the addition of CAPEX and OPEX. | Fc: load factor | |

| CAPEX | LCOE corresponds to the addition of CAPEX and OPEX. | Fc: load factor D: project lifespan | |

| Present value (PV) | Each investor is free to choose their own inflation and discount rates to judge the economic feasibility of their projects. | : actual value : the savings made over a year. | |

| NPV | : initial investment : the discounted residual value is the resale price of the system at the end. | ||

| Heat recovered | : initial energy : energy recovered in the form of heat | ||

| Initial energy | : EMD electrical efficiency : Recovered electrical power |

References

- United Nations et Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Report of the Conference of the Parties on its Twenty-First Session, Held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015; Part one: Proceedings, Paris, FCCC/CP/2015/10; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jahangiri, Z.; Hendriks, R.; McPherson, M. A machine learning approach to analysis of Canadian provincial power system decarbonization. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 4849–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Canada’s Official Greenhouse Gas Inventory. Annex 13—Electricity in Canada. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/779c7bcf-4982-47eb-af1b-a33618a05e5b (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Government of Canada. Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/net-zero-emissions-2050/canadian-net-zero-emissions-accountability-act.html (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Saffari, M.; McPherson, M. Assessment of Canada’s electricity system potential for variable renewable energy integration. Energy 2022, 250, 123757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, L. Barrières à l’Implantation de Projets d’Énergie Renouvelable dans les Communautés Hors Réseau des Régions Nordiques Canadiennes. Université de Sherbrooke. 2011. Available online: https://savoirs.usherbrooke.ca/handle/11143/7458 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Nieminen, G.S.; Laitinen, E. Understanding local opposition to renewable energy projects in the Nordic countries: A systematic literature review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 122, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satymov, R.; Bogdanov, D.; Galimova, T.; Breyer, C. Energy and industry transition to carbon-neutrality in Nordic conditions via local renewable sources, electrification, sector coupling, and power-to-X. Energy 2025, 319, 134888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Measuring regional variations and analyzing determinants for global renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2025, 244, 122644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miremadi, I.; Saboohi, Y.; Arasti, M. The influence of public R&D and knowledge spillovers on the development of renewable energy sources: The case of the Nordic countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 146, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, M.; Canizares, C.A.; Kazerani, M. Renewable Energy Alternatives for Remote Communities in Northern Ontario, Canada. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2013, 4, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, M.; Canizares, C.A.; Kazerani, M. Northern Lights: Access to Electricity in Canada’s Northern and Remote Communities. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2014, 12, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridier, L.; Hernández-Torres, D.; David, M.; Lauret, P. A heuristic approach for optimal sizing of ESS coupled with intermittent renewable sources systems. Renew. Energy 2016, 91, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fouly, T. Canada’s First Isolated Smart Microgrid: Hartley Bay, BC. 2020. Available online: https://ressources-naturelles.canada.ca/carte-outils-publications/publications/premier-micro-reseau-intelligent-isole-canada-hartley-bay-c-b (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- BBA. Les Défis d’Intégrer des Sources d’Énergie Renouvelable sur les Réseaux Électriques Autonomes. 2019. Available online: https://www.bba.ca/ca-fr/publications/défis-dintegrer-source-energie-renouvelable-sur-les-reseaux-electriques-autonomes (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Colbertaldo, P.; Agustin, S.B.; Campanari, S.; Brouwer, J. Impact of hydrogen energy storage on California electric power system: Towards 100% renewable electricity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9558–9576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwaine, N.; Foley, A.M.; Morrow, D.J.; Al Kez, D.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X.; Best, R.J. A state-of-the-art techno-economic review of distributed and embedded energy storage for energy systems. Energy 2021, 229, 120461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multon, B.; Robin, G.; Erambert, E.; Ahmed, H.B. Stockage de L’énergie Dans les Applications Stationnaires. In Proceedings of the Colloque Energie Électrique: Besoins, Enjeux, Technologies et Applications, Belfort, France, 18 June 2004; pp. 64–77. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-00676113v1/document (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Deusen, Z.L.D. Role of energy storage technologies in enhancing grid stability and reducing fossil fuel dependency. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1055–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Ram, S.; Thekkepat, K.; Lee, Y.-S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Lee, S.-C. Influence of oxidation on hydrogen storage properties in titanium-based materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xue, B.; Zhou, C.; Huang, K.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Yu, J. The carbon-clean electricity-lightweight material nexus of the CCS technology benefits for the hydrogen fuel cell buses. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 99, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagem, N.A.; Ebeed, M.; Alqahtani, D.; Jurado, F.; Khan, N.H.; Hafez, W.A. Optimal design and three-level stochastic energy management for an interconnected microgrid with hydrogen production and storage for fuel cell electric vehicle refueling stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 87, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, G.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Oni, B.A. A comprehensive review of underground hydrogen storage: Insight into geological sites (mechanisms), economics, barriers, and future outlook. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egermann, P.; Jeannin, L.; Perreaux, M.; Seyfert, F. Optimizing the design and use of underground hydrogen storage facilities with a Linear Programming approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 99, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, B.A.; Bade, S.O.; Sanni, S.E.; Orodu, O.D. Underground hydrogen storage in salt caverns: Recent advances, modeling approaches, barriers, and future outlook. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 114951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Li, Y.; Lou, Y.; Wei, T.; Yan, X.; Kobayashi, H.; Qi, D.; Tan, M.; Li, R. Gold-decorated Pt bimetallic nanoparticles on sulfur vacancy-rich MoS2 for aqueous phase reforming of methanol into hydrogen at low temperature and atmospheric pressure. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2025, 693, 120137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabu, B.; Veng, V.; Morgan, H.; Das, S.K.; Brack, E.; Alexander, T.; Mack, J.H.; Wong, H.-W.; Trelles, J.P. Hydrogen from cellulose and low-density polyethylene via atmospheric pressure nonthermal plasma. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Tu, Z.; Chan, S.H. Recent development of hydrogen and fuel cell technologies: A review. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 8421–8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirgama, K.; Samylingam, L.; Aslfattahi, N.; Kiai, M.S.; Kok, C.K.; Yusaf, T. Advancements and challenges in numerical analysis of hydrogen energy storage methods: Techniques, applications, and future direction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 125, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, V.R.; Pereira, I.B.; Vieira, R.d.S.; Aires, F.I.d.S.; Dari, D.N.; Félix, J.H.d.S.; de Lima, R.K.C.; dos Santos, J.C.S. Challenges and innovations in green hydrogen storage technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 113, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Gao, W.; Chi, S.; Wang, X.; Zheng, J. Development status and challenges of high-pressure gaseous hydrogen storage vessels and cylinders in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 214, 115567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrizi, M.Z.; Abdi, J.; Rezakazemi, M.; Salehi, E. A review on recent advances in hollow spheres for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 17583–17604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhao, P.; Niu, M.; Maddy, J. The survey of key technologies in hydrogen energy storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 14535–14552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jie, Y.; Zhou, D.; Ma, X. Underground hydrogen storage in depleted gas reservoirs with hydraulic fractures: Numerical modeling and simulation. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.L.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, C. Numerical investigations into the comparison of hydrogen and gas mixtures storage within salt caverns. Energy 2024, 311, 133369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, D.D.P.R.K. Bulk storage of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 34527–34541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, T.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, D. Development and Application of Hydrogen Storage. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2015, 22, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateti, S.; Zhang, C.; Du, A.; Periasamy, S.; Chen, Y.I. Superb storage and energy saving separation of hydrocarbon gases in boron nitride nanosheets via a mechanochemical process. Mater. Today 2022, 57, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Niu, F.; Wu, Z.; Gao, S.; Huang, Y. Reversible conversion between bicarbonate and formate in solid state “storage ball” for chemical hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-L.; Sun, Z.Y.; Fu, B.; Huang, Q. Unleashing the power of hydrogen: Challenges and solutions in solid-state storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, S0360319925010341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Shao, Z.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Weng, H.; Mohamed, M.A. A coordinated planning method of hydrogen refueling stations and distribution network considering gas-solid two-phase hydrogen storage mode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 100, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5 °C Climate Goal; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2020/Dec/IRENA_Green_hydrogen_cost_2020.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- I.E. Agency. Global Hydrogen Review 2024. International Energy Agency. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- I.E. Agency. Global Hydrogen Review 2025. International Energy Agency. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2025 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- I.E. Agency. Towards Hydrogen Definitions Based on Their Emissions Intensity. International Energy Agency. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/towards-hydrogen-definitions-based-on-their-emissions-intensity (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- U.S.D. of Energy. Hydrogen Shot: A Bold Decadal Vision for Reducing the Cost of Clean Hydrogen. DOE. 2021. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-shot (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- da Silva, F.T.F.; Lopes, M.S.G.; Asano, L.M.; Angelkorte, G.; Costa, A.K.B.; Szklo, A.; Schaeffer, R.; Coutinho, P. Integrated systems for the production of food, energy and materials as a sustainable strategy for decarbonization and land use: The case of sugarcane in Brazil. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 190, 107387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Shen, X.; Kammen, D.M.; Hong, C.; Nie, J.; Zheng, B.; Yao, S. A generation and transmission expansion planning model for the electricity market with decarbonization policies. Adv. Appl. Energy 2024, 13, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, G.; Dumbrava, V.; Lazaroiu, A.C.; Kalogirou, S. Analysis of urban network operation in presence of renewable sources for decarbonization of energy system. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongsheng, C.; Ndifor, E.Z.; Olayinka, A.-O.T.; Ukwuoma, C.C.; Shefik, A.; Hu, Y.; Bamisile, O.; Dagbasi, M.; Ozsahin, D.U.; Adun, H. An EnergyPlan analysis of electricity decarbonization in the CEMAC region. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 56, 101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiora, S.C.; Bamisile, O.; Hu, Y.; Ozsahin, D.U.; Adun, H. Assessing the decarbonization of electricity generation in major emitting countries by 2030 and 2050: Transition to a high share renewable energy mix. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.R.; Beiron, J.; Marthala, V.R.R.; Pettersson, L.; Harvey, S.; Thunman, H. Combining exergy-pinch and techno-economic analyses for identifying feasible decarbonization opportunities in carbon-intensive process industry: Case study of a propylene production technology. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 25, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.; Bisulandu, B.-J.R.M.; Ilinca, A.; Rousse, D.R. Hybrid Wind–Redox Flow Battery System for Decarbonizing Off-Grid Mining Operations. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, A.; Rousse, D.R.; Bisulandu, B.-J.R.M.; Ilinca, A. Enhancing Energy Sustainability in Remote Mining Operations Through Wind and Pumped-Hydro Storage; Application to Raglan Mine, Canada. Energies 2025, 18, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2021; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; Available online: https://www.irena.org/publications/2022/Jul/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2021 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Schmidt, O.; Melchior, S.; Hawkes, A.; Staffell, I. Projecting the Future Levelized Cost of Electricity Storage Technologies. Joule 2019, 3, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hydrogen Type/Pathway | GHG Footprint (kg CO2-eq/kg H2) | Energy Required & Efficiency (Typical) | LCOH—Indicative (Today → 2030+) | Production Today & 2030 Outlook | Utilisation by Sector (Today→2030) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grey (natural gas, Steam Methane Reforming—SMR, unabated) | ≈10–12 (NG SMR); coal-based ≈22–26 | SMR uses ~44.5 kWh/kg (NG as process heat/feedstock); small electricity. Overall efficiency ~65–75% LHV (typical literature). | Highly gas-price dependent: ≈$0.6–1.0/kg at very low NG prices; ≈$2.9–4.2/kg at EU 2023 gas prices; +~$1/kg per $100/tCO2eq carbon price (indicative). | Dominant: nearly two-thirds of 97 Mt (2023) from unabated NG; ~20% from coal. Low emissions <1%. | Mainly refining & chemicals today; new uses negligible (<1%). Shift to low emissions expected first in existing uses. |

| Blue (NG with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) SMR/ATR) | ≈1.5–6.2 (capture rate & methane leakage dependent) | SMR + CCS: ~49 kWh/kg NG + ~0.8 kWh/kg el. at ~93% capture; ATR + CCS: ~47 kWh/kg NG + ~3.7 kWh/kg el. (93–94% capture). | Indicative: ≈$1.0–1.4/kg in low-gas regions; ≈$3.3–4.7/kg at high gas prices; less sensitive to carbon price at high capture rates. | Part of <1% low emissions today. Announced low-emissions H2 could reach ~37–49 Mt/yr by 2030 (subject to FIDs/policy). | Expected to decarbonize current hydrogen uses first (refining, ammonia, methanol); potential growth in steel/DRI. |

| Green (electrolysis w/renewable sources) | ≈0–0.8 from RE electricity manufacturing embedded emissions (up to ~2.7 incl. full embedded ranges) | Electrolysis ~50 kWh/kg (incl. compression to 30 bar); current Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) systems ~55–58 kWh/kg. Efficiency ~60–70% (LHV). | Indicative today: often ~$3–8/kg (electricity-price driven). Targets: $1–2/kg by 2030s in favourable regimes (e.g., DOE “Hydrogen Shot” $1/kg by 2031). | <1% of supply today; rapid project pipeline, but many delays. Announced low-emissions H2 (incl. green) ~37–49 Mt/yr by 2030 (uncertain realisation). | Today: minimal in final energy sectors; by 2030, growth expected in steel, heavy transport, shipping/aviation fuels where policy support exists. |

| Pink (electrolysis w/nuclear) | ≈0.1–0.3 (depends on nuclear power lifecycle intensity) | Same electrolyzer needs as green (~50–55 kWh/kg). Potentially high utilisation if coupled to baseload nuclear. | Cost depends on nuclear power price & utilisation; ranges overlap green where low-cost nuclear is available. | Very small today; niche projects under discussion where stable nuclear baseload exists. | Potential in existing industrial hydrogen demand near nuclear plants; broader uptake depends on policy/regulation. |

| Turquoise (methane pyrolysis to H2 + solid C) | ≈2–16 (driven by NG upstream emissions & electricity for plasma/heating; no direct process CO2) | Representative variant: ~62 kWh/kg NG + ~14 kWh/kg electricity (plasma). | Early-stage; costs uncertain and highly site/tech dependent; could compete with blue if low-emission power & cheap gas available. | Pilot/demonstration scale today. | Potential in chemicals and materials (solid carbon co-product markets); trajectory uncertain to 2030. |

| Site | Network Connection | Distribution of Production | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Katinniq | Connected | 68.9% | |

| Mine 2 | Connected | Wind turbines 9.5% | Total 12.5% |

| Generators 3% | |||

| Mine 3 | Connected | 2.8% | |

| Qakimajurq | Connected | 3.5% | |

| Baie Déception (port) | Off-grid | 3.3% | |

| Kikialik | Off-grid | 7.5% | |

| Donaldson (airport) | Off-grid | 0.5% | |

| Decarbonization Scenarios | Electricity | Heat | Vehicles and Equipment | Heavy Transport | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heating | Drying | |||||

| 1 | 25 kV electrical network without heat | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | 25 kV electrical network without drying | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 3 | 25 kV electrical network with heat | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 4 | Vehicles and equipment | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| 5 | Heavy transport | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 6 | Total decarbonization | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rated power | 3 MW per unit | Enercon E82 E4 |

| Hub height | 78 m | Cold-climate kit included |

| Rotor diameter | 82 m | |

| Cut-in wind speed | 2.5 m/s | |

| Rated wind speed | 14 m/s | |

| Cut-out wind speed | 28 m/s | |

| Annual production (2021) | 8509 MWh/turbine | Measured on-site |

| Capacity factor | ~32% | Based on 2021 data |

| Cold-climate adaptations | Anti-icing, reinforced materials, autonomous restart | |

| Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) | 1700–1800 $/kW | Higher due to Arctic transport/foundations |

| Operating Expenditure (OPEX) | 50–60 $/kW/year | Maintenance, spare parts |

| Lifetime | 20–25 years | Reduced under Arctic conditions |

| Replacement/repowering | Blades, gearboxes mid-life | After 10–15 years |

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Multiple Caterpillar/EMD units | Total installed capacity 28 MW |

| Unit size | 3.3 MW each | Average |

| Maximum demand covered | 21 MW | Peak (2019–2021) |

| Efficiency | 58.2% | ~42% dissipated as heat (partly recovered) |

| Fuel | Diesel shipped & stored annually | |

| Operating profile | Baseload, frequent cycling | |

| Fuel cost (2021) | 33 M$CAD | |

| Carbon tax (2021) | 6.5 M$CAD | |

| O&M cost | 2.5 M$CAD/year | ~13% deviation vs. model |

| Total annual cost | 42.5 M$CAD | Diesel + O&M + tax |

| Lifetime | 20–25 years | Major overhauls 40–50k h |

| Fuel consumption | ~12,000 L/day per unit | ~4.4 ML/year/unit |

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | Lithium-ion (utility-scale) | With flywheel |

| Nominal capacity | 200 kWh | |

| Power rating | 200 kW | |

| Response time | ms to seconds | Grid support |

| Functions | Load balancing, spinning reserve, V/f stabilization | With flywheel |

| CAPEX | 600–800 $/kWh | Higher in Arctic |

| OPEX | 2% of CAPEX/year | |

| Lifetime | 10–15 years | 2% degradation/year |

| Replacement | After 8–10 years | Mid-life modules |

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nominal capacity | 1 MW | Modular |

| Production rate | 20 kg H2/h | At full load |

| Specific consumption | 52–55 kWh/kg H2 | |

| Efficiency | 60–65% | LHV |

| Operating pressure | 30 bar | |

| Dynamic response | Sub-second | |

| CAPEX | 1000–1200 $/kW | ~30–40% reduction projected by 2030 |

| OPEX | ~3% of CAPEX/year | Maintenance, stack |

| Lifetime | 60–80k h | 10–15 years |

| Stack replacement | Every 7–10 years | 30–40% CAPEX |

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Storage type | Pressurized gas tanks | |

| Pressure | 30 bar | Compatible with PEM |

| Storage capacity | Scenario-dependent | Hundreds of kg H2 |

| Role | Balances daily/seasonal fluctuations | |

| CAPEX | 500–700 $/kg H2 stored | Higher in Arctic |

| OPEX | 2% of CAPEX/year | |

| Lifetime | 20–30 years | Inspections 5–10 years |

| Scalability | Modular |

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | LT-PEMFC | Modular |

| Nominal power | 1 MW | |

| Efficiency | 50–60% | Electrical |

| Start-up time | Seconds–minutes | Dynamic |

| Fuel | H2 at 30 bar | |

| Integration | Backup power supply | |

| CAPEX | 700–1400 $/kW | Higher Arctic costs |

| OPEX | ~3% of CAPEX/year | Maintenance |

| Lifetime | 20–30k h | ~7–10 years |

| Stack replacement | Mid-life | |

| H2 consumption | 0.08–0.09 kg/kWh |

| Raglan Mine 25 kV Network | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Model | Reality | Gap [%] |

| Quantity of electrical energy produced in the year [MWh] | 154.9 | 157 | 1.3 |

| Number of liters of diesel consumed [ML] | 37.2 | 37.3 | 0.4 |

| Number of tCO2eq [tons] | 97,475 | 104,059 | 6.4 |

| Wind power production [MWh] | 17,042 | 17,017 | 0.01 |

| Year 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs | Model | Mine Data | Gap [%] |

| OPEX | 2,162,000 $ | 2,494,000 $ | 13% |

| Cost of diesel | 32,896,000 $ | 33,010,000 $ | 0.3% |

| Carbon tax | 6,500,000 $ | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 42,507,800 $ | N/A | N/A |

| Section | Energy Consumed | Data | Average Power in MW | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Electricity | Hourly schedules | 17.8 | 41.2% |

| Drying the ore | Heat | Averages | 6.75 | 15.6% |

| Glycol heating | Heat | Hourly schedules | 6.59 | 15.2% |

| Auxiliary heating | Heat | Averages | 2.08 | 4.8% |

| Mining equipment | Electricity | Averages | 6.77 | 15.7% |

| Surface vehicles | Electricity | Averages | 0.32 | 0.7% |

| Toyota pickup trucks | Electricity | Averages | 0.26 | 0.6% |

| Mining trucks | Fuel | Averages | 2.63 | 6.2% |

| Total | N/A | N/A | 43.2 | 100% |

| Power Consumption | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2019 | Year 2020 | Year 2021 | |

| Maximum power [kW] | 20,390.85 | 20,886.96 | 21,007.42 |

| Electricity consumed [kWh] | 146,370,985 | 144,836,291 | 154,959,758 |

| Component | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Wind Turbines | 14 | 22 |

| Wind Turbine Power [MW] | 42 | 66 |

| PEM electrolyzer [MW] | 14 | 20 |

| Storage tank [kg] | 67,000 | 147,000 |

| PEMFC [MW] | 9.2 | 13.8 |

| Converter [MW] | 14.4 | 20.2 |

| Electricity Production on the 25 Kv Network | Case 1 | Case 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [GWh] | [%] | [GWh] | [%] | |

| By the EMD | 104.2 | 43.9 | 57.8 | 18.2 |

| By the wind turbines | 119.2 | 50.3 | 238.6 | 75.1 |

| By PEMFC | 13.8 | 5.8 | 29.5 | 9.3 |

| Total | 237.4 | 100 | 317.8 | 100 |

| Penetration of renewable electricity into the network | 133.1 | 56.1 | 268.1 | 84.4 |

| Excess electricity | 41.5 | 31 * | 75.4 ** | +23.7 |

| Diesel consumption reduction [ML] | 10.3 | 22 | ||

| CO2 reduction estimation [tCO2eq] | 26,989 | 57,646 | ||

| Components | Total CAPEX | OPEX Per Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In M$ | In % | In M$ | In % | |||||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | |

| E-82 E4 wind turbine | 73.5 | 147.0 | 52.0 | 47.0 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 74.8 | 73.9 |

| Electrolyzer | 9.8 | 17.4 | 6.9 | 5.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 12.3 | 10.8 |

| H2 tank | 40.2 | 115.2 | 28.5 | 36.8 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 6.3 | 8.9 |

| Fuel cell | 9.2 | 16.7 | 6.5 | 5.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| Converter | 8.6 | 16.5 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| Total system | 141.3 | 312.7 | 100 | 100 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 100 | 100 |

| Index | Over 15 Years | Over 20 Years | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | |

| NPV | 15.4 | 27.83 | 82.7 | 173.8 |

| Discounted NPV | −43.5 | −104.9 | −19.9 | −54.0 |

| Payback period [years] | 12.8 | 12.8 | ||

| Case | System Configuration | Renewable Penetration | Diesel Savings | CAPEX (M$) | ROI (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 (PEMFC) | 47 WT (141 MW), 30 MW electrolyzer, 295,000 kg H2 tank, 29 MW PEMFC | 89% | 24.4 ML | 484.5 | 16.6 |

| Case 2 (SOFC) | 28 WT (84 MW), 25 MW electrolyzer, 120,000 kg H2 tank, 16 MW SOFC, diesel boilers | 88.6% | 24.3 ML (+1.9 ML with TCC) | 268.9 | 11.6 (10.7 with TCC) |

| Element | Case 1 (PEMFC, No Cogeneration) | Case 2 (SOFC, Cogeneration) |

|---|---|---|

| Wind turbines | 67 (201 MW) | 35 (105 MW) |

| Electrolyzer capacity | 69 MW | 49 MW |

| Hydrogen storage | 400 t | 245 t |

| Fuel cell capacity | 42 MW (PEMFC) | 22 MW (SOFC) |

| Electricity production | 644 GWh (100% renewable) | 343 GWh (100% renewable) |

| Heat production | Electricity is assumed equivalent to heat demand | 113 GWh (27% renewable from SOFC cogeneration, 73% diesel boilers) |

| Excess electricity | 160 GWh (24.8%) | 56 GWh (16.4%) |

| Diesel consumption avoided | 37.3 ML (100%) | 37.3 ML (100%) + 2.3 ML with TCC |

| Total CAPEX | 705 M$ | 411 M$ |

| Main CAPEX contributor | Wind turbines (50%) | Wind turbines (45%) |

| ROI/NPV (15 years) | 15.5 years/NPV negative | 12 years (11 with TCC)/NPV negative |

| Element | Case (PEMFC System) |

|---|---|

| Wind turbines | 19 (54 MW) |

| Electrolyzer capacity | 11 MW |

| Hydrogen storage | 100 t |

| Fuel cell capacity | 8.5 MW (PEMFC) |

| Electricity production | 179 GWh (100% renewable) 90.6% wind turbines and 9.4% PEMFC |

| Heat production | Not applicable |

| Excess electricity | 72 GWh (40%) |

| Diesel consumption avoided | 8.5 ML (100%) |

| Total CAPEX | 182.4 M$ (55% wind turbines, 33% H2 tank) |

| Total OPEX | 3.2 M$ (79% wind turbines, 7.3% H2 tank, 7.6% electrolyzer) |

| ROI/NPV | years/NPV negative (15 years) |

| Element | Case (Hydrogen Trucks) |

|---|---|

| Wind turbines | 8 (24 MW) |

| Electrolyzer capacity | 15 MW |

| Hydrogen storage | 75 t |

| Converter | 15 MW |

| Fuel cell capacity | (H2 only for trucks) |

| Electricity/H2 production | 68 GWh H2 (100% renewable) |

| Heat production | Not applicable |

| Excess electricity | Not applicable |

| Diesel consumption avoided | 5.5 ML (100%) |

| Total CAPEX | 114 M$ (35.7% wind turbines, 39.3% H2 tank) |

| Total OPEX | 2.1 M$ |

| ROI/NPV | 17.7 years/NPV negative (for 15 and 20 years) |

| Element | Case 1 (PEMFC, No Cogeneration) | Case 2 (SOFC, Cogeneration) |

|---|---|---|

| Wind turbines | 102 (306 MW) | 66 (198 MW) |

| Electrolyzer capacity | 90 MW | 59 MW |

| Hydrogen storage | 500 t | 345 t |

| Fuel cell capacity | 54 MW (PEMFC) | 33 MW (SOFC) |

| Electricity production | 966 GWh (100% renewable) (89.7% wind turbines; 10.3% PEMFC) | 628 GWh (100% renewable) (89.6% wind turbines, 10.4% SOFC) |

| Heat production | Electric heating assumed | 134 GWh (29% renewable, 71% diesel; +43% with TCC) |

| Excess electricity | 281 GWh (21%) | 183 GWh (29%) |

| Diesel consumption avoided | 53.3 ML (100%) | 42.8 ML (80%); 48.4 ML with TCC |

| Total CAPEX | 975 M$ | 655 M$ |

| Main CAPEX contributors | Wind turbines (55%) Hydrogen tank (31%) | Wind turbines (53%) |

| Total OPEX | 22 M$ | 14.5 M$ |

| Main OPEX contributors | Wind turbines (80%), Electrolyzer (8%), Hydrogen tank (7%) | Wind turbines (77%), Electrolyzer (9%), Hydrogen tank (7%) |

| ROI | 21.1 years | 19.2 years (14.8 with TCC) |

| NPV (15 years) | Negative | Negative |

| The Scenarios | Number of ML of Diesel Saved | Decarbonization of the Electricity Production of the 25 kV Network | Integration of Renewable Heat into the 25 kV Network | Decarbonization of Total Energy Consumption in Raglan Mine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 C1 | 10.3 | 27.6% | 0.0% | 19.3% |

| S1 C2 | 22 | 59.0% | 0.0% | 41.3% |

| S2 C1 | 24.4 | 65.4% | 55.3% | 45.8% |

| S2 C2 | 20.9 | 56.0% | 17.4% | 39.2% |

| S2 C2 TCC | 22.8 | 61.1% | 57.0% | 42.8% |

| S3 C1 | 37.3 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 70.0% |

| S3 C2 | 28.7 | 76.9% | 27.2% | 53.8% |

| S3 C2 TCC | 31 | 83.1% | 47.5% | 58.2% |

| S4 | 5.5 | N/A | N/A | 10.3% |

| S5 | 8.5 | N/A | N/A | 15.9% |

| S6 C1 | 53.3 | 100% | 100% | 100.0% |

| S6 C2 | 42.8 | 100% | 29.2% | 80.3% |

| S6 C2 TCC | 48.4 | 100% | 59.4% | 90.8% |

| The Scenarios | ML of Diesel Saved | CAPEX |

|---|---|---|

| S1 C1 | 10.3 | 141.3 |

| S1 C2 | 22 | 312.1 |

| S2 C1 | 24.4 | 484 |

| S2 C2 | 20.9 | 269 |

| S2 C2 TCC | 22.8 | 269 |

| S3 C1 | 37.3 | 705 |

| S3 C2 | 28.7 | 410 |

| S3 C2 TCC | 31 | 410 |

| S4 | 5.5 | 114.3 |

| S5 | 8.5 | 182.4 |

| S6 C1 | 53.3 | 974 |

| S6 C2 | 42.8 | 655 |

| S6 C2 TCC | 48.4 | 655 |

| The Scenarios | ROI (Years) | Discounted NPV Over 15 Years (M$) | NPV (M$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 C1 | 9.5 | −43.5 | 15.4 |

| S1 C2 | 10.1 | −104.9 | 27.83 |

| S2 C1 | 15.8 | −276.2 | −149.3 |

| S2 C2 | 18.6 | −79 | 35.8 |

| S2 C2 TCC | 13.2 | −57.18 | 70.68 |

| S3 C1 | 15.5 | −404.3 | −210.3 |

| S3 C2 | 12 | −147.9 | 10.4 |

| S3 C2 TCC | 11 | −121.3 | 52.8 |

| S4 | 17.7 | −64.8 | −34.8 |

| S5 | 19.3 | −98.5 | −48.1 |

| S6 C1 | 21.1 | −520 | −243.15 |

| S6 C2 | 19.2 | −162.8 | 139.9 |

| S6 C2 TCC | 14.8 | −156.5 | 146.8 |

| Scenario | Diesel Savings (ML/Year) | CO2 Avoided (t/Year) | CO2 Avoided (Mt Over 15 Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 Case 2 | 22.0 | ~59,000 | ~0.89 |

| Scenario 2 Case 2 (SOFC + TCC) | 22.8 | ~61,000 | ~0.91 |

| Scenario 3 Case 2 | 27.8 | ~74,500 | ~1.12 |

| Scenario 4 Case 2 | 39.0 | ~104,500 | ~1.57 |

| Scenario 5 Case 2 | 48.0 | ~129,000 | ~1.94 |

| Scenario 6 Case 1 | 53.3 | ~143,000 | ~2.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azin, H.; Mungyeko Bisulandu, B.-J.R.; Ilinca, A.; Rousse, D.R. Decarbonizing Arctic Mining Operations with Wind-Hydrogen Systems: Case Study of Raglan Mine. Processes 2025, 13, 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103208

Azin H, Mungyeko Bisulandu B-JR, Ilinca A, Rousse DR. Decarbonizing Arctic Mining Operations with Wind-Hydrogen Systems: Case Study of Raglan Mine. Processes. 2025; 13(10):3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103208

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzin, Hugo, Baby-Jean Robert Mungyeko Bisulandu, Adrian Ilinca, and Daniel R. Rousse. 2025. "Decarbonizing Arctic Mining Operations with Wind-Hydrogen Systems: Case Study of Raglan Mine" Processes 13, no. 10: 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103208

APA StyleAzin, H., Mungyeko Bisulandu, B.-J. R., Ilinca, A., & Rousse, D. R. (2025). Decarbonizing Arctic Mining Operations with Wind-Hydrogen Systems: Case Study of Raglan Mine. Processes, 13(10), 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103208