Abstract

Crypto, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and the metaverse have taken a massive place in our daily conversations and are highly valued. Moreover, NFTs range from luxury fashion to art, and sound is no exception, although it still needs to be explored. Could this be a unique opportunity to go digital from creation to distribution? This study looks at sound NFTs and new avenues for digital audio communication. During the pandemic, podcasts have been exhausted, leaving space for new digital media business opportunities. We look at how sound has grown, assuming a prominent role in the new media ecosystem due to podcasts consumption. We explore NFTs and their evolution in different markets over the years, highlighting the space that sound content has gained on these platforms as new possibilities for dissemination, promotion, and sale. We use content analysis on marketplaces that provide sound NFTs to understand what audio content consumers can find and future opportunities.

1. Introduction

The pandemic significantly affected the last few years due to significant changes in communication dynamics in terms of production and consumption. Staying at home, many consumers turned to more traditional media, such as television [1]. Additionally, consumers introduced new elements to their media diets, such as podcasts, which “have become a key part of many lockdown routines with more consumption at home—though there has also been disruption to the daily commute, traditionally a key time for listening” [1] (p. 27). Nevertheless, the changes felt were not only about consumption. Production was also affected since the time spent at home opened new possibilities for anyone to create such content, with significant growth of new podcasts, following up on a trend already identified in the first year of the pandemic [2]. However, the year was also marked by challenges that intensified in business models since in-person events were limited, and a large part of the dissemination activity was mainly through streaming.

In this context, in which digital platforms have become decisive spaces for consumption and production and dissemination, old questions have come back to the conversation regarding revenue generation, but above all concern the business model that best can serve the media. If the impact of digital transformation on the media was felt quickly and intensely, the pandemic again introduced new doubts regarding the value chain and the ideal business model.

The shift to digital has quickly become a reality for consumers and our own perception of what we own is also now, more than ever, virtual [3]. Blockchain also opened a new avenue for control and ownership of assets from third parties, but also the possibility of monitoring such transactions [4,5].

However, in 2021, we also witnessed an expansion of the global non-fungible token (NFT) market [6]. Due to the demand for digital artwork, but also due to several creators, namely in the music field, NFTs appear as an opportunity “to find alternate revenue streams once the COVID-19 pandemic effectively cut off musicians from their primary sources of income—live shows and merchandise sales” [7].

The interest in cryptocurrencies from the public has indubitably increased during the pandemic. Concomitantly, this interest in cryptocurrencies and crypto-collectibles also contradicted the global market interest rates, whilst imposed lockdowns and the shift to digital lifestyles also encouraged this interest not from the general public, but also from academic researchers [8].

If indeed NFTs have shown determinant potential in decentralised markets and are often presented as incredible business opportunities, NFT technologies are still largely misunderstood and lack a global presence in the market from mainstream consumers [9]. This is also the case for the exploration of NFTs in the creative industries in academic and scientific literature. According to Wang et al.: “even though much literature on NFTs, from blogs, wikis, forum posts, codes and other sources, are available to the public, a systematic study is absent” [9] (p. 3). This is all the more crucial as most literature reviews available dive into NFTs in general but have yet to focus on creative industries.

Although very present on streaming platforms, the music industry is only starting to look at this new type of digital asset. Driven by the pandemic, there were many “artists both well-established and up-and-coming, who realised they could adopt a B2C model, and sell unique, tokenised versions of their songs, albums, and artwork” [7]. More and more, it has been seen as a new way for creators to market and sell their content; the truth is that, in 2021, NFTs assumed a new position concerning new possibilities for consumption and distribution, also in the sound field [10,11,12,13,14].

The advances were mainly in terms of music and available items on NFT platforms, such as songs, albums, and audio clips, which can also be used for musical composition. The question that arises is the importance of NFTs in the more global digital audio communicative ecosystem. Can these platforms represent a new space to be explored, for example, by podcasters? Will the still unexplored territories of cryptocurrencies be an opportunity for creators in the sound field to get paid for their work without going through the major streaming platforms? Can NFTs represent a paradigm shift in the traditional dynamics of sound production and distribution?

These are some of the questions that guide us throughout this work, which assumes an essentially exploratory aspect, as we have done in other works [15]. NFTs are still little explored in comparison to the overwhelming amount of literature on cryptocurrencies; this is due to the fact that NFTs are still underdeveloped in many fields where researchers point out their potential, whilst there is still little data to support clear findings, but also because NFTs are a part of transdisciplinary fields [8].

Insofar as more than definitive answers, we seek to understand the possibilities of the universe of audio NFTs and what these can represent in terms of production, distribution and business. Therefore, to learn how NFTs could redefine the future of digital audio communication, we start this work with a look at the importance that sound has gained, especially in recent years, in the media ecosystem. We then look at the emergence of NFTs and their growth in the most varied activities of the creative industries. Finally, we focus our attention on the intersection between digital audio communication and NFTs, thus opening the way to the empirical dimension of the work. On the one hand, this involves identifying the NFT platforms dedicated to audio and, on the other hand, the type of audio content that we find on generalist platforms.

The data collected through the analysis will allow us to understand whether NFTs can effectively represent a paradigm shift in the way the sound universe will work in the future. Secondly, we aim to identify paths that can be explored by the media and producers, who can now market their work on the blockchain through NFT marketplaces, thus controlling the value of the products and democratising access to them.

2. Literature Review

Firstly, our literature review will look at digital audio communication as a field, highlighting that digital audio consumption has been growing in recent years [1,2,16,17]. In order to understand this growth, it is necessary to think about changes in consumption habits and the set of trends that have placed voice and audio as central elements in the relationship and interaction with technological devices [18]. In this first moment of the literature review, we highlight the importance of podcasts in the growth of digital audio communication while reflecting on a possible paradigm shift in terms of business models that can best serve the sound ecosystem.

In order to start this research by comprehending the different definitions of NFTs [14], we will approach some of the most used definitions in the current literature, establishing the basis for this particular study and grasping not only what NFTs are but why and how creative industries explore them [8,9]. After that first approach, we will look at the evolution of NFTs from first creation to historic selling and the evolution of crypto-collectibles in the creative industries. Lastly, we will join these fields together, as the scope of our study is to observe the NFTs’ possible implications for digital audio communication.

2.1. An Audio-Driven Revolution in the Digital Communication Ecosystem

For several years, the image was the main protagonist of the communicative ecosystem. The visual dimension was gaining importance, even before the expansion of the Internet, to become, through its potentialities, dominant over the other modes of communication. We also verified that “inside the Internet, we find a rhetoric that is scathingly based on visual culture, a culture that is founded on simplicity, speed and emotions where ‘seeing is enough to be’ and where repeat is inform (Ramonet 1999)” [19] (p. 36).

However, suppose the media ecosystem was built, for several years, around rhetoric dominated by the visual component. In that case, we cannot ignore the changes that have been verified in recent years, namely the growth of the importance of audio.

Although we still live in a society dominated by screens, we also see fatigue [18], which turned out to be one of the reasons why audio and voice gained renewed importance. Nevertheless, this is just one reason that helps explain the paradigm shift that we have seen in the communicative ecosystem. After all, consumption habits themselves have explained the importance that sound and voice have gained. The consumption and production of podcasts, the growth of smart speakers, the development of voice-controlled wearable technology, and the increase of voice-automated searches are just some of the trends in recent years that have shown how voice and audio have become central in the communication environment [1,2,16,17,18,20,21]. In this context, “the exponential multiplication of interconnected audio devices with tens of thousands of devices of all kinds, Artificial Intelligence and the maturation of a multiplicity of technologies associated with voice and sound have produced the phenomenon called Voice First” [18] (pp. 4–5).

Suppose it is true that several factors contributed to voice and audio becoming protagonists in the media ecosystem. In such a case, some contributed more significantly to this paradigm shift. One of the main factors responsible for the importance that audio has gained is podcasts, with some authors speaking of a ‘Golden Age’ of podcasting [22], while others refer to an “Audio Media Revolution” [23].

Whichever expression we use, the objective is the same, to highlight how podcasts became popular and contributed decisively to the growth of sound streaming platforms, placing sound as one of the main communicative trends in recent years [24]. However, it is also important to remember that the growth in importance of podcasts was gradual, that is, it was mainly from 2014 “with Apple’s inclusion of a built-in podcasting app on every iPhone” [23] (p. 1). Later that year, with the launch of the podcast ‘Serial’ (This American Life, 2014–2018), we witnessed a proper consolidation of this “(…) creative medium distinct from radio, with its own unique modes of not just dissemination but also production, listening, and engagement” [23] (p. 2).

In this period, which some authors call the ‘Second Age of Podcasting’ [25], we see not only a growth in the consumption of podcasts but also in the production itself [1,2,16,17,20]. In addition, we see a greater interest in companies and brands [2,8] without forgetting the scientific research on sound content itself, which has multiplied [21,26].

In addition to the aforementioned reports, and the more comprehensive works on the revolution introduced by podcasts in the media ecosystem [21,23,27], we found that many studies began to analyse podcasts as a radio remediation strategy [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]; the opportunities that podcasts have brought to journalism [35,36,37,38]; podcast consumption trends by different audiences [24,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]; the influence of the pandemic on the production and consumption of podcasts [46,47,48,49]; the use of podcasts in different areas of expertise [50,51,52,53,54]; and the new possibilities of immersion introduced by technology through podcasts [55,56].

Our objective in this study is not to make a systematic review of studies carried out on podcasts. We highlight only a few examples from different perspectives in the Portuguese, Brazilian, and Spanish contexts, thus demonstrating that much of the growth of the importance of the sound ecosystem is due to podcasts.

However, we can verify that few works address the issue of audio business models in general and podcasts in particular. Perhaps the main reason is that podcasts have consolidated themselves as a DYI medium, both in terms of production and communication and dissemination [24,26].

Thus, suppose that “the podcast is one of the media sectors most conducive to entrepreneurship and individual initiative” [28] (p. 5). We must also consider that with its growth and the entry on the scene of new actors, namely the large distribution platforms, new challenges arose. Platformization emerges as one of the biggest since “the tendency for media to be located on platforms that media makers do not control has had profound effects on the business” [57] (p. 1689). If democratisation in production and consumption has always been a distinctive element of podcasts, the use of platforms raises new questions regarding the nature of podcasts themselves. Since “even though podcasting is built upon the open architecture of RSS, commercial pressures and the desire of market players to capitalize on the “winner-take-all” features of platforms are shaping the trajectory of the medium’s current development” [58] (p. 1). In this context, issues related to authorship and monetisation gain relevance in a discussion “between the free essence that has always characterised the medium and the necessary subjection to metrics, models and other constraints dictated by advertisers” [28] (p. 6). Thus, in this direct distribution and digitisation context, platforms such as Patreon or Twitch have been used as facilitators for creators to engage directly with their audience and grow their visibility online [11]. From artists to podcasters, these platforms are now widely used as a complementary source of income and communication.

It is precisely in this context that we present this paper. We aim to highlight the importance of podcasts and the expected growth for this medium in the coming years [59]. Moreover, we expect to showcase a set of other trends in terms of digital audio communication [8] and the need to think about monetisation and the best strategies to give power back to content creators. Therefore, we consider it necessary to reflect on the potential of NFTs to offer producers a new medium to present and market their work on the blockchain through NFT marketplaces, thus allowing creators to control the supply chain and rights associated with their work.

Arenal et al. highlight that “previous research has mainly focused on the examination of the business models of streaming services from the point of view of the innovation players (digital platforms) and/or the traditional dominant intermediaries (record labels and publishers). However, not all innovation-driven transformations are sustainable” [60] (p. 1). Through qualitative research, the authors “(…) conclude that DMSPs foster an asymmetric value chain in which the creative players barely capture value while technology-based innovations increase the capability of DMSPs to generate and capture value” [60] (pp. 1–2).

This is precisely the dimension that this paper explores in the possible avenues that can be considered for audio content creation and distribution in terms of business models, transactions, and ownership.

2.2. NFTs: An Introduction

As the concept of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) continues to grow, it seems essential to define a simple concept. Therefore, we will line up some of the most used definitions. Per Shahriar and Hayawi: “NFTs are cryptographic tokens that were initially built on the Ethereum blockchain but more recently adapted by other blockchains […] NFTs are different from fungible tokens like Bitcoins, where each token is similar in value to the other ones and can easily be swapped. The non-fungible aspect of NFTs ensures that each token is unique and consequently provides the holder with ownership rights over a digital asset” [61] (p. 2).

This definition encompasses the dimensions of value and exchange, which are very important in the definition of NFTs, although often overlooked. The value that the token encompasses depends on several factors such as its ownership, more than the artefact itself, as explained by Shilina: “A token as a unit of account is a record in a distributed blockchain and is controlled by a computer algorithm of a smart contract, in which the values of the balances on the accounts of token holders are recorded, making it possible to transfer them from one wallet to another. Non-fungible tokens were originally created as special token standards to support the use of blockchain in computer games, which include the Ethereum ERC-721 standard (which is representing non-fungible digital assets) and the more recent ERC-1155 standard (which offers ‘semi-fungibility’)” [62,63]. What appears to be also harder to grasp for a majority of consumers is the difference between NFTs and cryptocurrencies. According to Wang: “Bitcoin is a standard coin in which all the coins are equivalent and indistinguishable. In contrast, NFT is unique which cannot be exchanged like-for-like (equivalently, non-fungible), making it suitable for identifying something or someone in a unique way. To be specific, by using NFTs on smart contracts (in Ethereum), a creator can easily prove the existence and ownership of digital assets in the form of videos, images, arts, event tickets, etc.” [9] (p. 2).

Moreover, crypto-collectibles are relevant because of the unique value they are subjected to, according to Chevet: “like art pieces stored on a blockchain, any form of data, (image, text, sound), that is uniquely identified by a blockchain. Unlike cryptocurrencies which are fungible, meaning that any Bitcoin is equivalent in value to any other Bitcoin, just like a dollar is equivalent to any other dollar, non-fungible assets are unique and differentiated from one another” [64] (p. 5). The amount of information and traceability and interoperability allowed in such transactions is also what makes NFTs a soon-to-be preferred option for IP protection [9]. However, the authors also note that: “NFTs represent little more than code, but the codes to a buyer have ascribed value when considering its comparative scarcity as a digital object” [9] (p. 2).

Furthermore, NFTs allow acquirers to prove they own a unique item and that they are the sole possessor of such an item [14], which is quite relevant in the creative industries.

However, NFTs also have a gaming dimension. Like movie or gaming figurine collectors, they have become a digital phenomenon for those who have already adopted lifestyles based on passions such as anime, comic books, or video games, becoming more and more open to the creative arts. According to Jiménez: “Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) are digital assets that represent objects like art, collectibles, and in-game items. They are traded online, often with cryptocurrency, and are generally encoded within smart contracts on a blockchain” [65] (p. 3).

To this definition, the author also adds the physical dimensions of such tokens: “A non-fungible token (NFT) is a type of cryptographic token on a blockchain that represents a unique asset. These can either be entirely digital assets or tokenised versions of real-world assets. As NFTs are not interchangeable with each other, they may function as proof of authenticity and ownership within the digital realm” [65] (p. 4).

This last aspect of the nature of NFTs has been exploited, especially in the fashion industry, namely through RTFKT’s footwear drops and, perhaps most famously, the Cybersneaker [66]. Therefore, in this study, we understand NFTs’ most straightforward nature: unique digital assets that can be acquired, collected, and traded. With the emergence of NFTs in the past few years, especially following the digital revolution experienced during the pandemic, we will now look into this phenomenon through creative and communicative perspectives.

Rauman defines NFTs as a “nascent technology that operates as digital assets representing both tangible and intangible items of value” [12] (p. 10). It is important to note that, although the terms are used interchangeably, fungible assets, such as bitcoin or dollars, are very different from non-fungible assets. Bradley poses that “Fungible assets are divisible, which means they can be broken down into smaller fractions of units sharing the same properties. These fungible assets are indistinguishable from each other, which is important for their use as a payment mechanism. Non-fungible assets are indivisible and unique, meaning that the asset cannot be split up to represent a fraction of the whole, and each asset is different from another, with a distinct code underlying each asset” [12] (p. 10).

NFTs can also allow creators to grow in different markets and engage directly with consumers, followers, and fans, but also to trace ownership and revenue through tracking royalties. Per Folgieri et al., these contracts can also allow for a concise yet approachable way to look at the problem of ownership of content creators: “also known as digital contracts or, according to the Ethereum naming convention, smart contracts, are blockchain-based digital signatures used to authenticate digital assets. The simplest approach consists in transferring the ownership of the composition via NFT and keeping the royalties as the author” [11] (p. 63).

There is also the question of the dematerialisation of property and intellectual claims through NFTs. For Sestino et al., this is why NFTs are neither products nor services but something else in the middle. According to the authors: “Unlike services, however, NFTs do not require the owner’s direct participation, a large skilled workforce, or even a specific physical location to be consumed. Unlike products, one cannot easily flaunt NFTs in the same way as a sports car or jewellery, especially outside of virtual environments” [14] (p. 5). This is all the more relevant since the creator’s economy referenced earlier is also interested in the possible interactions and traceability of NFTs. Moreover, for many creators, going all digital is already a reality.

2.3. The Emergence of NFTs

The first known NFT, Kevin McCoy’s ‘Quantum’ created in 2014, was sold seven years later in 2021 for USD 1.4 million at a Sotheby’s auction, showing the world that NFTs were officially acknowledged by ‘traditional’ art auctions around the world. Although McCoy’s NFT is often referred to as the first one, another happening a year prior is also recognised as a maker of the history of NFTs. The coloured coins, appearing in 2012, marked a transition in how data was carried through bitcoins, as per Crypto Dukedom: “The functioning of coloured coins was not very different from non-fungible tokens as we know them: their purpose is to represent a multitude of resources within metadata. The main reason why coloured coins were invented is to open the door to developing new features in Bitcoin. The ability to create tokens linked to things in the real world and for these to be supported by a blockchain network presented a unique opportunity” [67] (p. 15).

Cryptokitties is another historical and relevant element to mention when speaking about the emergence of crypto-collectibles: “A collection of artistic images representing virtual cats that are used in a game on Ethereum that allows players to purchase, collect, breed, and sell them on Ethereum. In December 2017, CryptoKitties congested the Ethereum network. By many considered a chief example of the irrationality driving the cryptocurrency market in 2017, CryptoKitties remained the only popular example of NFTs for almost 2 years” [68] (p. 1).

Since these first steps, NFTs have become very desirable, especially in the last few years, with recent sales, such as Christie’s March 2021 auction, where ‘Beeple’, the higher priced transaction of the kind, totalled USD 69 million [68,69,70,71]. Moreover, according to Charter and Davis: “Blockchain has also leapt forward with respected organisations such as Sotheby’s acknowledging that NFT marketplaces are here to stay. Two years ago, these marketplaces were viewed as niche, but they have seen huge transaction growth in the last year: for example, between October 2020 and March 2021, transaction volume on the OpenSea NFT marketplace (the largest) has grown over 100 times” [72] (p. 17).

The year 2020 saw an emergence of NFTs’ distribution and offerings, with the market growing exponentially to attain “10 million US dollars in March 2021, thus becoming 150 times larger than it was 8 months earlier” [68] (p. 2).

The concept of NFTs’ relevance has been hard to grasp and continues to baffle many others about the actual emotional value of owning a non-fungible token that is entirely digital [73]. According to Crypto Dukedom, NFTs stand in this often-paradoxical limbo that can be explained by the value each subject attributes to something, not the object itself: “Therefore, the value is not something intrinsic to the product. It is not one of its properties, but simply the importance that we attribute to the satisfaction of our needs in relation to our life and our well-being” [67] (p. 22).

However, there is still a lot to unpack for many about the potential of NFTs for the creative industries, especially within the technicalities of the NFTs themselves, as observed by Patrickson: “NFTs can be bought and sold at any stage before, during or after a creative process. Ownership can also be divided into more liquid micro-shares to make expensive works and collective sponsorship options more accessible. This sort of asset is a complicated notion, nevertheless, because NFT registration does not include the right to own proprietary visual elements, and the image can still generally be copied. The key point for collectors is that only registered owners have the right to trade that file” [74] (p. 587).

In this sense, the market is highly determinant in the emergence of NFTs because the main target is the early adopters of this new craze, tech-savvy GenZ and GenY males [75]. An insight report by the Business of Fashion states that 65% of US GenX and GenY consumers value digital ownership as important [76].

Moreover, the market that has perhaps most explored NFTs is gaming [68], with a high dissemination of crypto-collectibles among online gaming platforms [77]. However, in the past two years, the creative industries have taken a double look at NFTs, taking them more seriously as a business opportunity. Creators regard NFTs as a possible way to mark and track their work, and how they earn revenue can also be organised and more transparent [12] and creates a more direct-to-consumer approach than ever.

2.4. Markets Explored with NFTs in the Creative Industries

As pointed out by many studies, technologies and the digital paradigm our societies face have taken many forms. Creative industries have adopted many digital trends and new avenues to disseminate, communicate, and create. Technologies have been used in many situations to revamp media or adapt to consumers’ needs, such as podcasts or digital garments for fashion [50,75]. Nevertheless, one of the main game-changing aspects of embedding technologies into creative industries is for the creators themselves, who do not necessarily need intermediaries to reach their customers [62]. This is a noticeable opportunity with the emergence of industry 4.0 and the pandemic years [72].

According to Rauman: “Any individual who creates content to be consumed is a player in the creator economy. YouTubers, graphic designers, Instagram or TikTok influencers who monetise through paid posts, chefs who share their work virtually to subscribers, advertisers, travel bloggers who visit and review specific hotels for a fee, individuals who sell art on online marketplaces, and musical artists are all examples of content creators” [12] (p. 3).

This is also the case for any content creator, as other artists have widely explored NFTs, whether familiar with the technology or not. For smaller-scale creators, this also means increasing their revenues by cutting the shareholders to a minimum [8]. Furthermore, for content creators, this model also represents a new drive for the ecosystem of creators and the community based on this economic system, where creators and consumers can interact but also act as both parties [12]. This paradigm shift is also evident in transactions, where third parties such as alternative digital banking and payment solutions such as PayPal are no longer needed [12]. NFTs have quickly become an all-stop solution, at least conceptually, to shift the intellectual property paradigm of creatives. According to Sestino et al. “the momentum is driven mainly by three factors: the opportunity for creators to exercise and transmit the rights associated with such items; the possibility for users to boast about owning such objects; and the facilitation of marketing and advertising strategies that can leverage such items’ uniqueness” [14] (p. 13).

Crypto-collectables, like non-digital assets explored in traditional creative industries, are most predominantly organised and proposed in collections of items [68], which is also the case in fashion. Therefore, the match made between NFTs and fashion is not farfetched. From NFTs to D2A (Direct-to-Avatar) business models and digital clothing for unique social media content, fashion can be considered one of the early adopters of these new digital trends.

For fashion, surfing on the NFT trend has come through the gaming industry [75], with partnerships between gaming companies and fashion brands, such as Roblox and Vans, or more famously, Fortnite and Balenciaga [76]. Moreover, sportswear giants such as Adidas or Nike have also understood the value of going all-in with NFTs; an example is Nike’s recent acquisition of crypto and digital content creator studio RTFKT [78].

With approximately 70% of US GenZ and GenX consumers declaring their digital identity as necessary [76], the fashion industry has quickly adapted to this new medium, tackling more than just gamers and the tech-savvy youth [62], but also luxury consumers, with brands such as Prada or Louis Vuitton [79,80]. However, the future of fashion NFTs is still unsure, as target markets are somehow incompatible; from one side, there is a women-driven market, and on the other, there is a more man-oriented, early adopter type market [81]. Moreover, the issues with intellectual property and risks of NFTs are often used by sceptics [82,83,84].

Nevertheless, crypto-collectibles are now deemed attractive by individual creative artists, as per Charter and Davis: “Artists and creators recognising that digital art and goods are a viable revenue stream (e.g., digital premieres, avatars and digital fashion, unique goods on NFT marketplaces etc.)” [72] (p. 7). This is explained by the fact that common distribution channels for artists are scarce and highly dependent on the interest of the masses. According to Wang et al.: “NFTs transform their work into digital formats with integrated identities. Artists do not have to transfer ownership and contents to agents. This provides them impetus with lots of profits” [9] (p. 12).

Nevertheless, if many creative industries have already dabbled into NFTs and music is no stranger to the craze, little has been explored in scientific research around the theme of audio NFTs [62]. Therefore, it seems valid to look at the diverse ways in which audio content can be distributed through NFTs to add more opportunities for digital audio communication. The pandemic has also accelerated the process of a more direct-to-consumer approach from creators. According to Bradley: “with the absence of live events, artists have increasingly turned to sources that allow fans to pay for exclusive content. Through the use of NFTs, blockchain technology could provide a novel solution to this problem—a solution that will last much longer than the departure of live music” [12] (p. 6).

Thus, it is fair to say that NFTs already appear to be an appealing solution for creators in this approach to new markets and new approaches to digitised business models and direct distribution. It is, therefore, envisioned that audio content, such as podcasts, music, and audio streaming, could also follow in this direction.

2.5. NFT and Digital Audio Communication: A Path to Be Traced Together?

In 2019, Deloitte predicted that “the global audiobook market will grow by 25 per cent to US$3.5 billion. And audiobooks aren’t the only audio format gaining in popularity. Also predicting that the global podcasting market will increase by 30 per cent to reach US$1.1 billion in 2020, surpassing the US$1 billion mark for the first time” [48] (p. 106).

The digital audio ecosystem has been growing considerably. The consultant believes “audiobooks and podcasts are outgrowing their ‘niche’ status to emerge as substantive markets in their own right” [59] (p. 107).

Suppose it is true that “the expected growth in audiobooks and podcasts is part of a larger trend of better-than-you-might- think growth in audio overall” [59] (p. 108). In that case, we cannot forget that it has never been so important as it is today to discuss the business models that best apply to sound. In this context, the consultant understands that, although “podcasts could be a US$3.3 billion-plus business by 2025” [59] (p. 109), it is essential to start thinking about new ways of monetising sound content.

If we take the case of podcasts as an example, although the medium has been around for some time, it was only since 2014, and due primarily to the success of “Serial”, that this content began to reach more audiences and attract more audience sponsors. Let us think of another type of audio content. The situation is not very different insofar as, despite being increasingly consumed, this increase does not typically translate into income for its producers. The reason is simple, as in the case of podcasts, much of this content is available for free. Suppose the production of audio content has been considerably simplified over time, and today it is straightforward for anyone to produce the most varied types of content. In that case, the truth is that this DIY logic also constitutes a challenge in terms of monetisation. “So long as people can listen to thousands of hours of high-quality podcasts essentially for free, profit-motivated podcasters will have a hard time getting listeners to actually pay for content” [59] (p. 110).

Therefore, the question is how to monetise the produced content efficiently. However, many variables are associated with this issue, such as copying or sharing without permission. While the “Internet has granted all of us access to limitless content”, the truth is that “all types of digital media can be easily shared and replicated, with or without the permission of content creators”. Thus, “this digital abundance of data and the way it was distributed over the internet, it was always an issue for content creators, as their work could be copied and shared without approval and remuneration” [85] (p. 27).

In this context, we understand it is necessary to explore the potential introduced by NFTs in areas such as art or games, as we did in the previous point, to think about their application in the area of digital audio. In the case of music, there is still much to explore. However, the first steps have already been taken, with artists such as 3LAU, Grimes, and Deadmau5 defying music distribution and merchandising by approaching the public in a new way. Blockchain technology has clearly imposed itself as a relevant opportunity for the music industry, as well as other creative industries [12].

Among the many benefits that the adoption of NFTs can generate, we can highlight, on the one hand, the ease of “the exchange of music rights and creating a public record of ownership that can be used to resolve overlapping royalty claims” and, on the other hand, the possibilities of “opening the music rights market to the general public”, allowing “fans to invest in their copyrights directly”, without forgetting the “new ways to monetize music”, since “most NFTs marketplaces automatically pay out royalties to the creators whenever the NFTs are bought and sold” [86]. Furthermore, Rauman poses that “Blockchain’s core technology, which enables smart contracts and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), could be used to restructure and decentralise the music industry to be in alignment with the best interests of artists—the individuals responsible for driving the success of this industry” [12] (p. 1).

Despite this potential, we are aware that there are still several significant challenges concerning non-fungible tokens, especially because “NFTs are new, there is limited information on how existing laws and regulations apply to NFTs” [87] (p. 4). However, we cannot forget that “for the first time, content on the internet in the form of an NFT can be definitively owned by a specific person independent of a centralized intermediary, and this is unlocking exciting opportunities for digital commerce and engagement” [87] (p. 4). Nevertheless, the market is ultimately the decisive agent in innovative business models, which will be the case for audio NFTs as well. According to Lee: “Critics might respond that NFTs are different from other consumer items because they are virtual abstractions of something else. That is true to some extent, but we have no shortage of financial contracts and instruments that are abstractions of something else. A stock is an abstract ownership interest in a company” [88] (p. 53).

Thus, if “the music industry alone seems to be presenting the most illuminating litmus test for how blockchain technology could facilitate co-creation and co-ownership of intellectual property” [7], can we think of new opportunities for the entire digital audio ecosystem? It is precisely this path that we try to explore in this study. The evolution from Web2 to Web3 has allowed for many solutions for the music industry [10]. This new model allows creators to be at the core of their craft and decide of their own distribution. Moreover, according to Behal: “In Web2, profits and stock prices influenced most companies more than helping small creators who were publishing content. In other words, by creating a platform for artists to publish their music, Web2 companies could profit massively and not pay artists as much as they should have” [10] (pp. 2–3). This also implies that the whole industry could potentially shift with more direct access to content with niche artists and creators. Per Behal: “if there was a Web3 music streaming platform, they could create a free-to-mint NFT that users could receive by listening to music from artists with less than 10,000 followers or artists with less than 1,000,000 total music streams. This way, artists would be able to receive more listens in a period of time, potentially have more people follow them and join their community, and receive more money due to this event” [10] (p. 4).

As Shara Senderoff, Partner and President at music/tech investment firm Raised in Space, highlights: “Long term, NFTs and the idea of digital collectibles are very much here to stay. They represent an incredibly promising and important new revenue stream, for artists and for the music industry as a whole (…) We’re very much in the infancy of what digital collectibles and the tech that allows them to exist will become” [89] (p. 31).

So, if the expansion of NFTs is merely beginning and the sound ecosystem continues to grow, is this not the right moment to explore a new path altogether?

3. Methodology

In this research, we opted for a mixed-methods approach as it provides a deeper understanding of the platforms providing sound distribution as NFTs, using a comprehensive qualitative approach to digital audio communication and the evolution of the NFTs.

3.1. Context of the Approach

From early context to democratisation over the pandemic, we continue to approach the creative markets and industries that have dabbled into NFTs to adapt to the times, leading to the final point of the literature review on possible avenues in NFTs for sound design and digital audio communication. Secondly, we elaborate on the general public’s interest in audio NFTs since the beginning of the pandemic, using Google Trends to quantitatively track worldwide searches on key terms over the past two years.

The analysis exploring the Google Trends platform to indicate users’ interest in NFTs and audio was crucial to define tendencies and interest peaks of the general public. The general curiosity and interest that these keywords have generated in the last years reveal how consumers react and search for this information. It is also noted that these interests are related to technologies and transactions, such as NFTs, but specifically applied to sound, audio, and music.

Furthermore, Google Trends can be overlooked, but it provides essential data on internet users’ mentalities. The platform can treat and present the data of the billions of online queries conducted internationally every second of the day. The data also allows for nodes and clusters of search to be more precise and contextualise interest peaks by countries, regions, and specific times. This is especially relevant considering these queries vary highly with time and can be triggered by significant news and events. The “related searches” section also allows for context when some of the data presented stand confusing or lack further justification.

Google Trends was specifically preferred as a general overview of internet users, not specifically consumers of NFTs, to gauge the public’s general interest in NFTs and audio. Other browsers in consideration, such as Brave, which has been growing exponentially over the last few years [90], were not used, as they are very specific and not as generally used as Google. Moreover, Brave does not provide a tool similar to Trends, and other tools are more specific to business ownership and market analysis or focus on specific continents, not the general public’s interests on a worldwide scale.

Then, through a quantitative approach, we observe the recent interest of the public in audio NFTs and conduct a content analysis where data obtained in multiple NFT marketplaces will be analysed and discussed. Content analysis is defined as “the systematic, objective, quantitative analysis of message characteristics (…). Its applications can include the careful examination of face-to-face human interactions; the analysis of character portrayals in media venues ranging from novels to online videos; the computer-driven analysis of word usage in news media and political speeches, advertising, and blogs; the examination of interactive content such as video gaming and social media exchanges; and so much more” [91] (p. 19). In this study, we precisely apply this definition to assess the offerings of NFT platforms and their possible offerings and focus on audio content.

3.2. Criteria Used for the Content Analysis

The content analysis must be considered unobtrusive and objective [92]; hence, its use here must be seen as preferable for an objective outsider’s perspective on the audio NFT offerings. As we previously did in the literature review, we started to research global marketplaces that do not specify their offerings, taking indications from several articles ranking the most used NFT marketplaces (See Table 1). From that first selection, we encountered 117 platforms fitting that description, but only selected 34, as few of them were recommended in more than one article. Only those which were cited or referenced by at least 3 or more news articles or reports were selected (Table 1). We then extended our research to NFT marketplaces that offer audio content, and those which are specific to audio distribution [50,62,69].

Table 1.

Content analysis’ selection criteria.

It is important to note that the data collection was conducted during the months of December 2021 to March 2022; hence, new platforms that were launched since then were not considered in the selection, such as Reddit’s new NFT marketplace [93]. However, as of the moment, this research is concluding, and Golden’s query tool accounts for 269 active NFT marketplaces in all categories over the world [94].

Using these first indicators to select the platforms to observe, we then grouped these results into a table to summarise the current NFT offerings, with indications on provenience, type of offering, and distribution specification. With this final analysis, we aim at mapping the current offerings for audio NFTs and draw conclusions on the possible evolution of such platforms for more diverse audio content.

3.3. Procedure of Data Analysis

The first approach of the data collection and analysis regarded a more general approach to the public’s recent engagement with NFTs and, specifically, audio content distributed on NFT marketplaces. We, therefore, started our search for the terms displayed in the next section of this paper. After considering several different approaches and tools (as explained in Section 3.1), we focused on Google Trends to explore patterns on countries, keywords, and dates. From this first general overview, we then started the content analysis from the conceptual stage to relational analysis [91] and proceeded to analyse the 20 platforms presented in the next section.

4. Results and Discussion

Starting our analysis on interest and consumer awareness of NFTs for audio distribution, we decided to start our research using Google Trends to explore some of the queries most used worldwide, from the beginning of 2020 until the present time of this study.

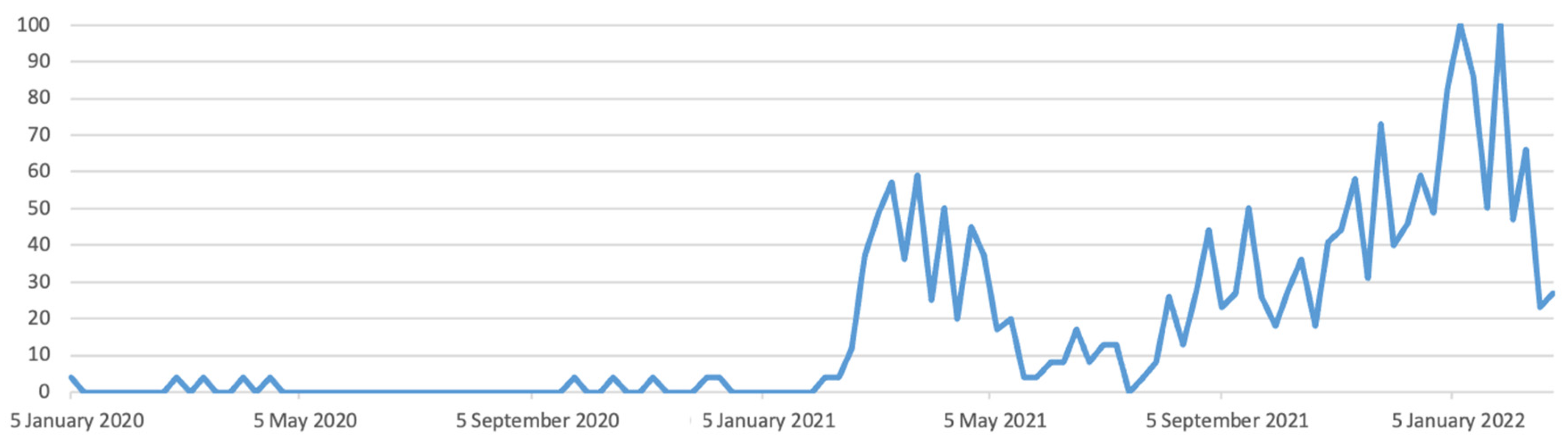

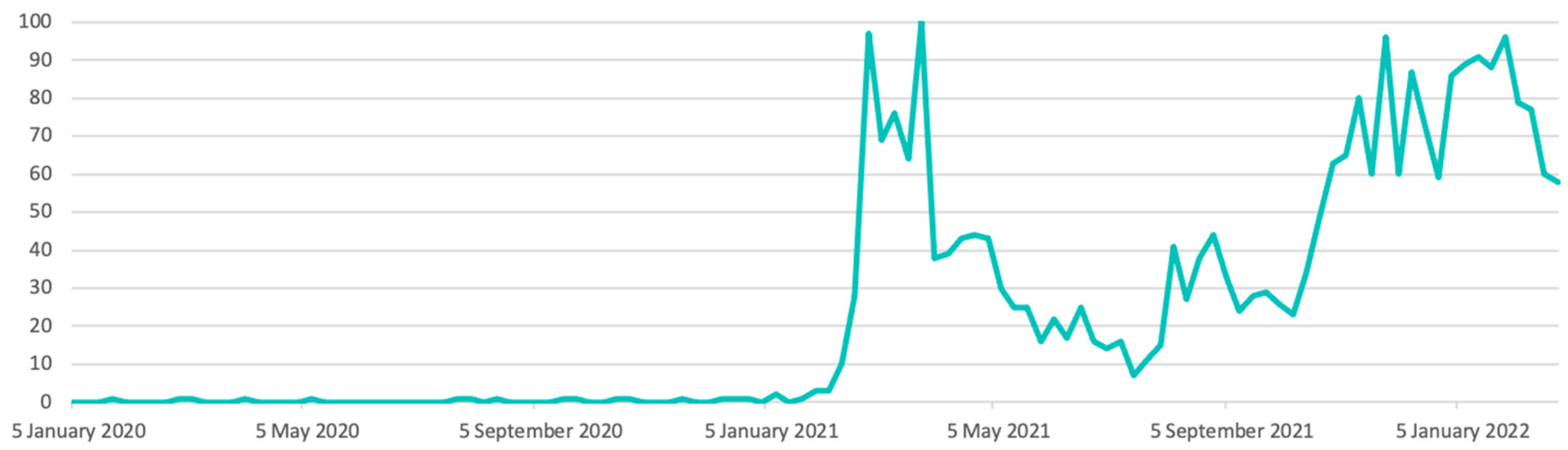

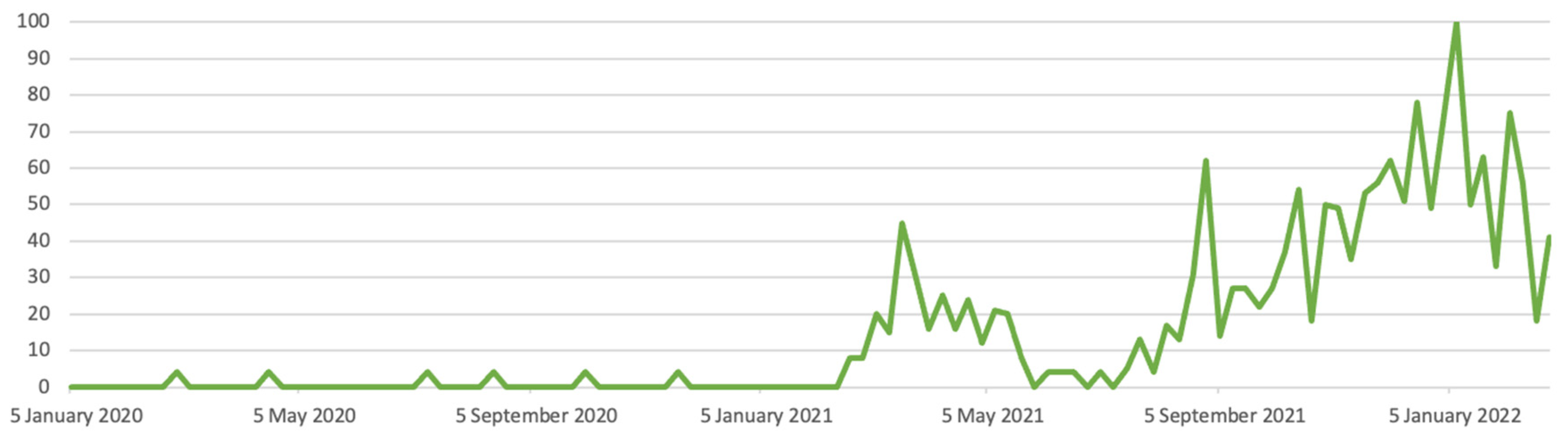

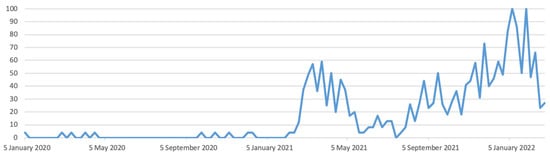

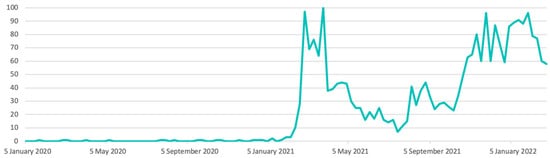

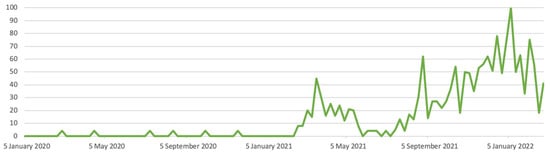

We used three different terms, “NFT Audio” (Figure 1), “NFT Music” (Figure 2), and “NFT Sound” (Figure 3), to explore the timeline evolution of those searches, presented in the following figures.

Figure 1.

Worldwide searched term on Google for “NFT Audio”.

Figure 2.

Worldwide searched term on Google for “NFT Music”.

Figure 3.

Worldwide searched term on Google for “NFT Sound”.

To better understand the data presented in the following figures, we propose a table to summarise Google Trends’ metrics and values (Table 2). According to the Google trends website: “numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means that there was not enough data for this term” [95].

Table 2.

Metrics and values used in Google Trends.

The graphic presented in Figure 1 shows the evolution of the search, worldwide, for the term “NFT Audio” from January 2020 to January 2022. Interestingly, the first significant peak of interest is in late March and April of 2021. This first peak could be due to an increase in interest from music artists in NFTs, such as Grimes’ collection sold in late February 2021 on Nifty Gateway [96]. Moreover, we can see that, starting in September 2021, the term was been increasingly searched for online until January 2022, when the graphic is seen attaining its all-time peak.

The same phenomenon can be observed in Figure 2, with two significant peaks in early 2021 and later a new increase over the months of September 2021 to January 2022. Such events are mostly due to the increase in global interest from the mainstream public through events such as Decentraland’s highly anticipated first metaverse festival in October 2021, and other subsequent events and music collaborations [97].

We also researched queries on Google containing “NFT Podcast”. However, through the results obtained, we realised that those queries were based on people looking for podcasts discussing NFTs. We, therefore, decided to exclude these results from the analysis.

We can observe significantly similar trends from those three queries, with a meagre interest over 2020 and a spike beginning in the first quarter of 2021. We can spot another peak in September 2021 and an overall all-time high interest on all topics from the end of 2021 until the beginning of 2022, which is consistent with some of the observations made in research on this topic [62,68].

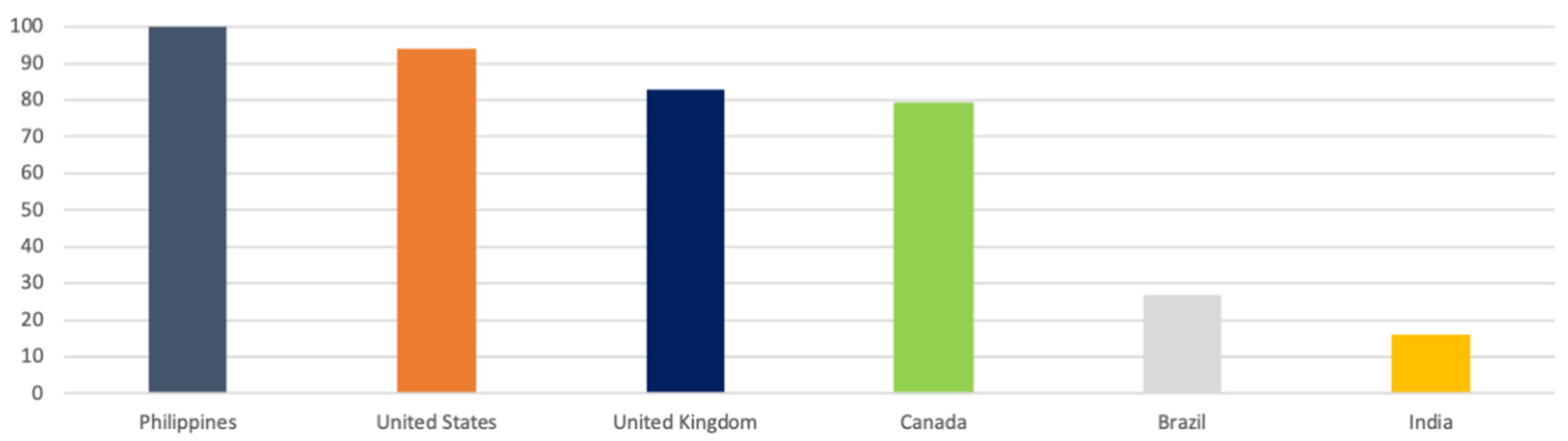

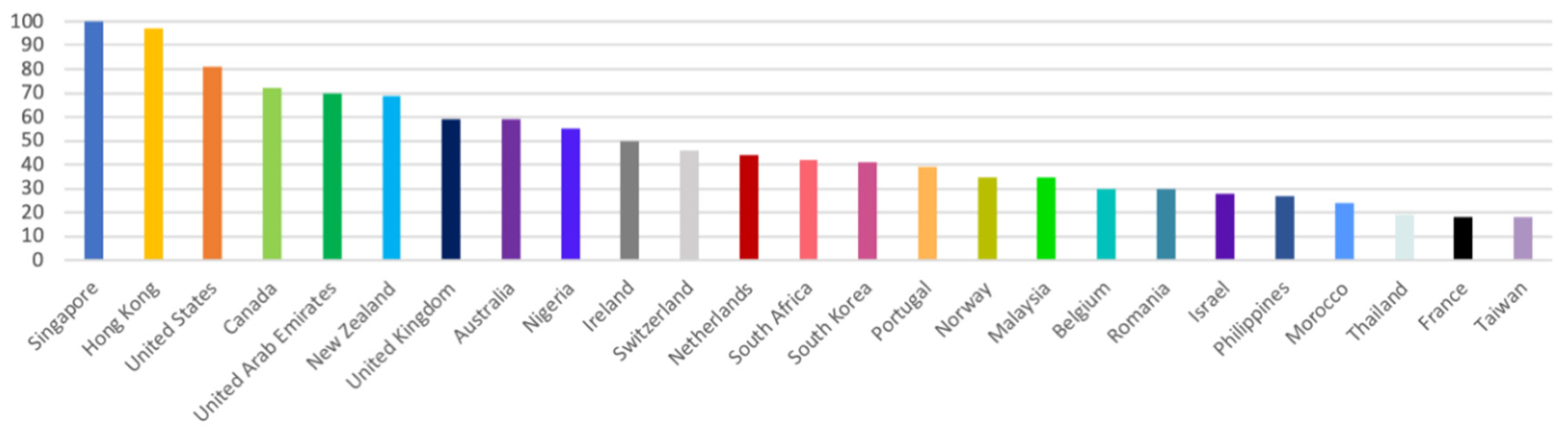

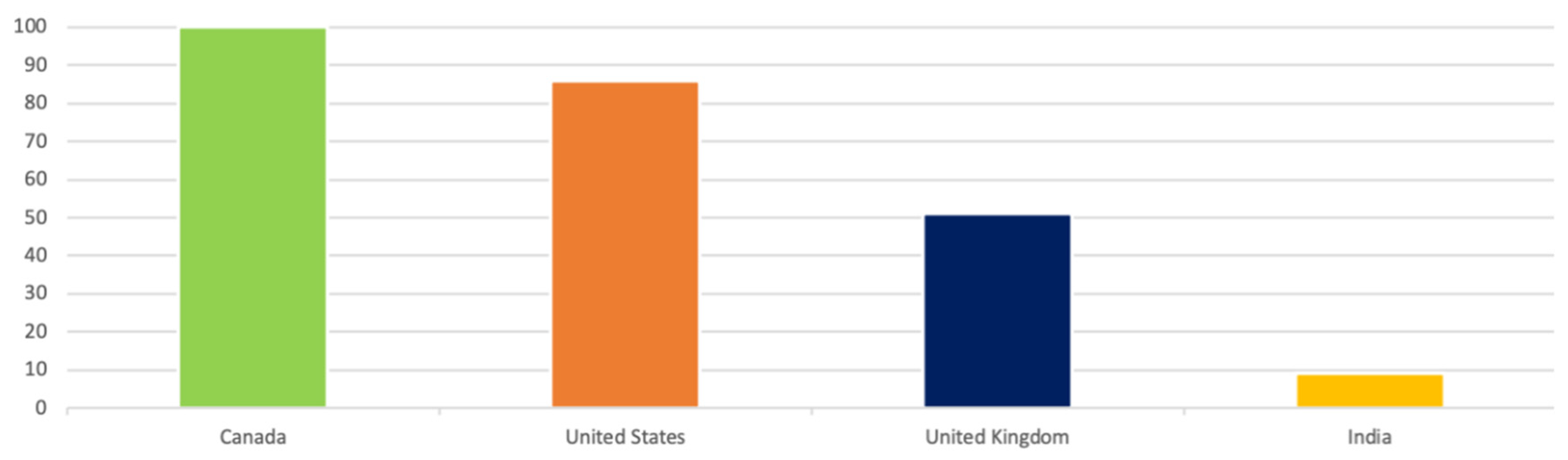

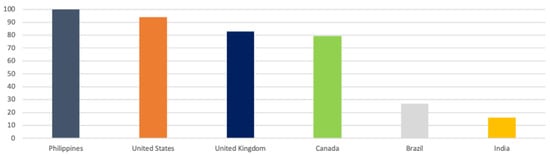

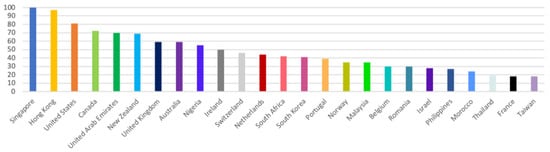

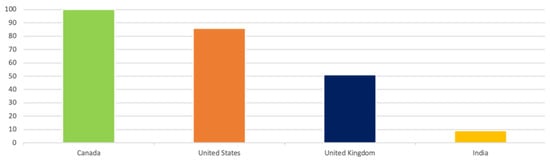

Moreover, we also considered the countries where those queries took place. For both “NFT Audio” (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and “NFT sound” (Figure 6), the majority of the searches came from the same countries, whereas 39 countries have searched for NFT Music in total with only significant numbers presented in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Google search for “NFT Audio” by country.

Figure 5.

Google search for “NFT Music” by country.

Figure 6.

Google search for “NFT Sound” by country.

Figure 4 only presents countries where a significant number of queries were made during the same timeframe as previously outlined (January 2020 to January 2022). It is important to take into account that the data does not provide absolute percentages, therefore, the higher score presented here by the Philippines does not necessarily show a higher interest in these terms when compared to more populated countries. According to the Google trends website: “A higher value means a higher proportion of all queries, not a higher absolute query count. So a tiny country where 80% of the queries are for ‘bananas’ will get twice the score of a giant country where only 40% of the queries are for ‘bananas’ [98].

However, there is definitely a high interest in Asian countries, as Figure 4 and Figure 5 both show a higher number of queries coming from the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

Moreover, Figure 5 presents a wider range of countries where queries for NFT music were spotted over the same time period. Countries range from several continents, from Asia to North America, Africa, Europe, and Australia. No countries from South America were high enough in this category to be presented, which could seemingly mean a low interest in music NFTs from this region so far.

In Figure 4 and Figure 6, we present all countries that searched for the related terms. There were very few countries from which those queries came, mainly from North America, the UK, India, and the Philippines, for the “NFT audio” search only. Having established this first global analysis based on trending research and starting with an analysis of existing NFT marketplaces, we took indications from several articles ranking the most used NFT marketplaces [69,70]. We then extended our research to marketplaces specific to audio NFTs.

Therefore, we ended up categorising a total of 20 NFT-dedicated platforms, of which 15 offer different NFT collections and audio NFTs. The other five do not propose audio NFTs specifically and have no offer at all or very few audio collectibles (Table 3).

Table 3.

NFT marketplaces under analysis.

When defining an audio NFT, we consider any crypto-collectibles that possess sound, any token containing a music track, audio animation, or sound effects.

We divided Table 3 into two portions, the first showing the marketplaces with a broader offering, whilst the second section shows the platforms dedicated to audio NFTS. Both sections present the token codes corresponding to the blockchains they are built on such as Ethereum (ETH), Flow (FLOW), or Polygon (MATIC). Our first observation is that the distribution is extensive, and many marketplaces have decided to venture into specific niches, such as sports NFTs, gaming NFTs, or metaverse NFTs.

Most platforms show transparency in terms of information, with complex transactions, ownership, bidding history, and detailed profiles of the NFT creators. As it is also visible in Table 3, Ether (ETH) is the token of choice for many of those observed.

Platforms corresponding to the Ethereum blockchain have been used widely in NFT marketplaces since 2017 [62]. On the other hand, some marketplaces only propose their tokens based on closed systems only used on their platforms, citing safety as their primary concern. However, all platforms provide wallet services for users to conveniently exchange their cryptocurrencies for tokens.

Moreover, most of the platforms presented here are start-ups created less than five years ago, such as OpenSea, founded in 2017. It is also worth noting that more than two-thirds of the platforms were founded in the USA.

Overall, another observation can be made regarding the UX and UI design of some of the marketplaces, causing difficulties in our research and observations. Some platforms lack information and filters to select specific NFTs, which cannot be agreeable to consumers. Such was the case for smaller platforms and music NFT marketplaces.

Another point worth noting is that sound NFT platforms, although scarce, seem to overlap in terms of the offerings by proposing mainly music or 2D/3D animations with sound effects. The overall slogans and motivation used by those music marketplaces is the possibility for artists to own their music and distribute it directly to their fans, in a B2C model, without having to recur to traditional labels, an argument also expressed on other platforms such as SuperRare. According to SuperRare’s website: “The future of the web belongs to creators. We’ve always believed artists are sovereign actors who should be able to control their own destiny. By enabling artists to mint custom contracts that reflect their own unique project themes or artistic brand, we hope many more will take the leap and become true sovereigns in every sense” [99].

However, NFT music marketplaces propose crypto-collectibles as digital merchandising tokens, with exclusive photographs of the artist or animated pictures rather than the songs themselves.

Therefore, we can identify a first opportunity for sound-recording artists to provide audio content through NFTs, such as experimental music, that would not fit or be accepted by their traditional labels. Moreover, there is also an opportunity to extend this value to audio content, such as informative, lifestyle, artistic, or opinion content.

The audio content available on these marketplaces is either entire songs or smaller audio clips. Thus, there is also an opening for other types of content, without any restrictions, such as independent podcasts, where podcasters could directly trade ownership with their listeners and earn rewards from their content production. On the other hand, considering that crypto-collectibles attract consumers with their visuals, the possibility to open space for video podcasts is intriguing, a content type that has attracted more consumers in recent years [100].

Keeping our focus on the audio marketplaces, we can observe that some of the music platforms highlighted during our research ended up being streaming platforms and, therefore, were not analysed to the same extent. However, it is worth noting that music streaming platforms such as Audius, Emanate, eMusic, or Opus have shown a growing interest in NFTs, mainly for merchandising purposes. Although, at this time, these platforms do not provide NFTs for sound distribution and were therefore not considered here.

Moreover, although not presented in the table, another platform worth noticing is Decentraland. This metaverse organised a metaverse festival in October of 2021, with over 80 artists, including music producer Deadmau5 [97]. Users can acquire all sorts of NFTs, such as plots and wearables, to participate in these digital events, and other platforms such as ceek.io aim to do the same. For artists, the emergence of NFTs has meant more than new ways to distribute their music directly to the public. They are also a way to market their brands digitally, such as creating related NFT art and collectables sold as merchandise [101] or organising their events and showcasing projects that might not have the same demand offline. Moreover, this opens new possibilities for content creators, who can opt for co-creation systems, allowing followers of their work to participate in the process, or collaborations with established artists and brands that can benefit from associating themselves with emerging digital creators.

On that note, an element seemingly crucial for those platforms is intellectual property, with issues on plagiarism, as well as fraud, as explained by NFT Showroom on their website: “By creating an NFT with a specified number of editions you are ensuring the scarcity of your art for your buyers. Once art is tokenized, it is important you do not tokenize the same creation again as that will negatively affect the value of your artwork and reputation. We reserve the right to restrict access to NFT Showroom if an artist is caught plagiarizing or fraudulently issuing multiple tokens of the same creation” [102].

Another side of this issue is also flagrant with recent fraudulent activities that caused NFT marketplace Cent to shut down its operations temporarily [83].

There is also a clear innovation leadership in audio NFTs from the music industry. Yet, if we consider sound as something more inclusive of all its forms, we can observe that NFTs still need to cover other audio formats.

Nevertheless, this interest from the general public has been growing. It was precisely this relation that we attempted to establish through our exploratory approach, not invalidating what the future can bring, as well as the importance of more studies inclusive of all forms of sound NFTs.

In sum, space for audio content to grow in the NFT marketplace is more than available. However, as NFTs’ evolution and value growth are uncertain and depend on how marketplaces will handle contracts and intellectual property in the future [82], where many possibilities are foreseeable, and, once again, with digital audio and NFTs, possibilities are endless.

5. Conclusions

This study attempted to question whether NFTs can be considered a possible avenue for digital audio communication in the future. The literature review established the evolution of crypto-collectibles in the creative industries to later focus on their application in the digital audio communication field. We observed some of the NFT marketplaces that include audio tokens and platforms that only focus on sound crypto-collectibles’ distribution through our analysis. The concept of value is what is at stake for the future of NFTs, as the concept of owning a digital token that is available for the world to see is somehow hard to grasp in a society that is still very attached to material possessions.

We believe this study is one of the few attempts at scientific research specifically focusing on NFTs and digital audio communication. Yet, we understand that our contribution is innovative and pragmatic in the way our views on the possibility of these two elements combined are discussed here. The major limitation of this study is the lack of scientific literature available on the specific topic of NFTs in the creative industries, and more specifically so for NFTs and audio communications. Therefore, we started by analysing scientific and academic literature on the broader spectrum of NFTs and crypto-collectibles. We also added other sources of information, such as reports, non-scientific articles, and so on. Moreover, finding specific information on NFT marketplaces is no easy task. Many are transparent about their creation and provenience, but others are hard to trace.

This study contributes to thinking about new opportunities for monetising the different types of content that result from a growing sound ecosystem. Suppose traditional business models are undergoing a profound transformation because of our advertising investment changes. In that case, it is necessary to start thinking about new strategies. This reflection is all the more critical as we know that platforms challenge creators to earn revenue despite being essential for discovering new content, such as podcasts. In this context, as is already happening with the music industry, we believe that NFTs can define a new future in digital audio communication, yet, the solution is still up for debate in this specific corner of the industry.

NFTs have the potential to ensure that creators of audio content are more fairly compensated for their work. Until now, it was fairly complex for creators to own rights to their creations. With NFTs, creators have the possibility of tracking their content distribution. The compensation can be more direct and fairer since non-fungible token transaction platforms can record ownership with unique metadata. It is also suggested that the actual challenge in sound NFTs is debated among artists and creators of audio content, as the ownership and openness of these creators to give up their source of revenue after selling an NFT would also represent a huge shift in the current business models applied in the music industry.

We are aware that there is still a lot of cluelessness and fear regarding everything that is crypto and NFT, and while there are risks, the truth is that not everything is transparent on current platforms, either. Therefore, this can be at least one first step to be taken.

We also need to further highlight the many challenges that need to be considered and tackled prior to launching NFTs as a one-stop solution for audio distribution; many problems will have to be solved, as is the case for all novel technologies, and the technology itself will also have to be dissected extensively in terms of policy making in order to be applied to such demanding and diverse industries.

As such, we believe that in order to create policies and solutions for such technologies, they need to be explored simply and be accessible to the masses, hence our attainable approach in this paper.

This topic is timely and relevant, leading us to believe that future research will be looking at more case studies as new marketplaces are created every day. Moreover, we recommend that researchers cross our present results with other communication fields or dive deeper into the consumers’ preparedness and interest in audio crypto-collectibles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.M. and C.E.F.; methodology, C.E.F.; validation, C.E.F. and R.M.; formal analysis, C.E.F. and R.M.; resources, R.M.; data curation, C.E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, C.E.F. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, C.E.F. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. The third party data used in this study are publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Malar Villi Nadeson, the Ngee Ann Kongsi Library, for her remarkable contribution to our literature review search.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Schulz, A.; Simge, A.; Robertson, C.T.; Nielsen, R.K. Reuters Institute. Digital News Report 2021-10th Edition; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford, UK; Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital_News_Report_2021_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Voxnest. 2020 Mid-Year Podcast Industry Report. The State of the Podcast Universe. Available online: https://blog.voxnest.com/2020-mid-year-podcast-industry-report/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Belk, R.; Humayun, M.; Brouard, M. Money, possessions, and ownership in the Metaverse: NFTs, cryptocurrencies, Web3 and Wild Markets. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.M.; Saraniemi, S. Trust in Blockchain-Enabled Exchanges: Future Directions in Blockchain Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.M.; Salo, J. Ethical Marketing in the Blockchain-Based Sharing Economy: Theoretical Integration and Guiding Insights. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emergen Research. Non Fungible Token Market by Type (Physical Asset, Digital Asset), by Application (Collectibles, Art, Gaming, Utilities, Metaverse, Sport, Others), by End-Use, and by Region Forecast to 2030. Available online: https://www.emergenresearch.com/industry-report/non-fungible-token-market (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Harris, C.; Langston, T. The Top 21 Music NFT Moments of 2021. Nft Now. NftNow. April 2021. Available online: https://nftnow.com/music/top-music-nft-moments-2021/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Bao, H.; Roubaud, D. Non-Fungible Token: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, R.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S. Non-Fungible Token (NFT): Overview, Evaluation, Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.07447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behal, P. Listen-to-Earn: How Web3 Can Change the Music Industry. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4150998 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Folgieri, R.; Arnold, P.; Buda, A.G. NFTs In Music Industry: Potentiality and Challenge. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2022, London, UK, 4–8 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauman, B. The Budding Disruption of Blockchain Technology upon the Current Structure of the Music Industry. Senior Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/466/ (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Li, N. Combination of Blockchain and AI for Music Intellectual Property Protection. Hindawi-Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4482217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestino, A.; Guido, G.; Peluso, A.M. Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs): Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, C.E.; Morais, R. A Review on Potential Technological Advances for Fashion Retail: Smart Fitting Rooms, Augmented and Virtual Realities. DObra[S]—Rev. Assoc. Bras. Estud. Pesqui. Moda 2021, 32, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.; Fletcher, R.; Schulz, A.; Simge, A.; Nielsen, R.K. Reuters Institute. Digital News Report 2020. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Edison Research and Triton Digital. The Podcast Consumer: A Report from the Infinite Dial. Available online: http://www.edisonresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-Infinite-Dial-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- IAB Spain. Libro Blanco Audio Digital. IAB Spain. Available online: https://iabspain.es/estudio/libro-blanco-audio-digital-2022/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Cardoso, G.; Espanha, R.; Araújo, V. Da Comunicação de Massa à Comunicação em Rede; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Voxnest. Relatório Voxnest Brasil 2019. The State of the Podcast Universe. Available online: https://blog.voxnest.com/podcastuniversereport/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Piñeiro-Otero, T.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M. Audio communication in the face of the renaissance of digital audio. Prof. Inf. 2022, 31, e310507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R. Part of the Establishment: Reflecting on 10 Years of Podcasting as an Audio Medium. Convergence 2016, 22, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Dann, L. Podcasting the Audio Media Revolution; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Otero, T. “Escúchanos, Hermana”. Los Podcast Como Prácticas y Canales Del Activismo Feminista. Rev. Incl. 2021, 8, 231–254. Available online: http://revistainclusiones.com/carga/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/12-Pineiro-Espana-Congreso-VOL-8-NUM-AbrilJunoo2021INCL.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Bonini, T. The ‘Second Age’ of Podcasting: Reframing Podcasting as a New Digital Mass Medium. Quad. Del CAC XVIII 2015, 41, 21–30. Available online: http://www.cac.cat/pfw_files/cma/recerca/quaderns_cac/Q41_Bonini_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Reis, A.I.; Ribeiro, F. Os novos territórios do podcast. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinares, D.; Fox, N.; Berry, R. Introduction: Podcasting and Podcasts—Parameters of a New Aural Culture. In Podcasting: New Aural Cultures and Digital Media; Llinares, D., Fox, N., Berry, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, J.; Santos, S.; Magalhães, C.; May, A.T.; Cardoso, P. O podcast como remediação da rádio e da televisão nos pequenos mercados: O caso português. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terol Bolinches , R.; Pedrero Esteban, L.M.; Pérez Alaejos , M. De la radio al audio a la carta: La gestión de las plataformas de podcasting en el mercado hispanohablante. Hist. Comun. Soc. 2021, 26, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R. Radio, Music, Podcasts-BBC Sounds: Public service radio and Podcasts in a Platform World. Radio J. Int. Stud. Broadcast Audio Media 2020, 18, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavilhas, J. La radio en el ecosistema mediático del siglo XXI: Estudio de caso en Portugal. Index Comun. 2020, 10, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delménico, M.; Parlatore, B.; Beneitez, M.E.; Clavellino, M.; Di Marzio, M.; Gratti, A.L. El podcast y el desafío de repensar lo radiofónico. Question/Cuestión 2020, 2, 1–18. Available online: https://perio.unlp.edu.ar/ojs/index.php/question/article/view/6335 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Sellas, T.; Solà, S. Podium Podcast and the Freedom of Podcasting: Beyond the Limits of Radio Programming and Production Constraints. Radio J. Int. Stud. Broadcast Audio Media 2019, 17, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PérezAlaejos, M.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M.; Leoz-Aizpuru, A. La oferta nativa de podcast en la radio comercial española: Contenidos, géneros y tendencias. Fonseca J. Commun. 2018, 17, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.I. O áudio invisível: Uma análise ao podcast dos jornais portugueses. Rev. Lusófona Estud. Cult. 2018, 5, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Vieira, J. Podcasts no Jornalismo Português—O Caso P24. Media J. 2021, 21, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.M. Informar através do som. O Podcast no ciberjornalismo português–Análise do P24. Prisma.Com 2021, 45, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Zuculoto, V. Da reportagem ao Podcast: Aproximação entre a reportagem radiofônica especial e o podcast CBN Especial. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Olmsted, S.; Wang, R. Understanding Podcast Users: Consumption Motives and Behaviors. New Media Soc. 2020, 24, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellstab, C.C. Marcelo Kischinhevsky-novas perspectivas para os estudos de podcast no Brasil. Rev. Alterjor 2022, 25, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Y.L.; Viana, L. ¿Es la podosfera femenina?: Una visión general brasileña de los podcasts presentados solo por mujeres. Razón Palabra 2021, 25, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, R.; Giacomelli, F.; Grafolin, T.; Rocha, F. Audience transformations and new audio experiences: An analysis of the trends and consumption habits of podcasts by Brazilian listeners. J. Audience Recept. Stud. 2021, 18, 381–405. Available online: https://www.participations.org/Volume%2018/Issue%201/22.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Quintino, C.L.; Del Bianco, N.R.; Oliveira Moura, D. Consumo de podcasts jornalísticos no cotidiano de jovens universitários brasileiros. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, N.; Avelar, K.; Martins, H.C. Podcast: A research trajectory and emerging themes: Podcast: Trajetória de pesquisa e temas emergentes. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L. Podcast studies: An overview of the state-of-the-art in Brazilian radio and sound media research. Contracampo-Braz. J. Commun. 2020, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonixe, L. Potencialidades do podcasting no jornalismo de saúde—Uma análise a três podcasts sobre a COVID-19 em Portugal. Comun. E Soc. 2021, 40, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisana, M.; Martins, R. Podcasting e pandemia. Da portabilidade e mobilidade ao confinamento e universos pessoais interconectados. Obs. (OBS*) J. 2021, 15, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, P.; Damázio, A. Podcastmente. Podcasts de saúde mental criados na pandemia COVID-19 em Portugal. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, L.; Mustafá, I.; Viana, L.; Balacó, B.A.F. Cartografia da produção de podcasts universitários no contexto da pandemia. Radiofonias–Rev. Estud. Mídia Sonora 2020, 11, 6–36. Available online: https://repositorio.ufc.br/bitstream/riufc/56281/1/2020_art_lchagas.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Fernandes, C.E.; Morais, R. Podcasts Are Fashionable Too: The Use of Podcasting in Fashion Communication. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Peixinho, A. A redescoberta do storytelling: O sucesso dos podcasts não ficcionais como reflexo da viragem. Estud. Comun. 2019, 29, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, C.; Gamboa, M.J.; Brites, L.; Oliveira, M. Dez minutos de conversa: Podcasting como recurso de formação multidimensional. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.J.; Salaverría, R. Examining Independent Podcasts in Portuguese ITunes. In HCI International 2020-Posters. HCII 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Villafranca, P. Estudio de casos de la ficción sonora en la radio pública, RNE, y en la plataforma de podcast del Grupo Prisa en España. Anu. Electrónico Estud. Comun. Soc. “Disert.” 2019, 12, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L. O áudio pensado para um jornalismo imersivo em podcasts narrativos. Comun. Pública 2021, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.S.; Morais, R. The revenge of audio: O despertar do som binaural na era dos podcasts e das narrativas radiofónicas. Media J. 2020, 20, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufderheide, P.; Lieberman, D.; Alkhallouf, A.; Ugboma, J.M. Podcasting as public media: The future of U.S. news, public affairs, and educational podcasts. Int. J. Commun. 2020, 14, 1683–1704. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/13548/3016 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Sullivan, J.L. The Platforms of Podcasting: Past and Present. Soc. Media + Soc. 2019, 5, 2056305119880002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Loucks, J.; Stewart, D.; Jarvis, D.; Arkenberg, C. Technology, Media, and Telecommunications Predictions 2020. Deloitte’s Technology, Media, and Telecommunications (TMT), Deloitte Insights. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/at/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/at-tmt-predictions-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Arenal, A.; Armuña, C.; Ramos, S.; Feijoo, C.; Aguado, J.M. Giants with feet of clay: The sustainability of the business models in music streaming services. Prof. Inf. 2022, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Hayawi, K. NFTGAN: Non-Fungible Token Art Generation Using Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the ICMLT 2022: 2022 7th International Conference on Machine Learning Technologies, Rome, Italy, 11–13 March 2022; Association for Computing Machiner: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilina, S. Blockchain and Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs): A New Mediator Standard for Creative Industries Communication. 2021, pp. 217–226. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sasha-Shilina/publication/356493275_Blockchain_and_non-fungible_tokens_NFTs_A_new_mediator_standard_for_creative_industries_communication/links/619e03223068c54fa519be3f/Blockchain-and-non-fungible-tokens-NFTs-A-new-mediator-standard-for-creative-industries-communication.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Wackerow. ERC-1155 MULTI-TOKEN STANDARD. Available online: https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/standards/tokens/erc-1155/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Chevet, S. Blockchain Technology and Non-Fungible Tokens: Reshaping Value Chains in Creative Industries. Master’s Thesis, HEC Paris, Paris, France, 2018. Academic Year 2017–2018. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3212662 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Jimenez, J.A. A Guide to Crypto Collectibles and Non-Fungible Tokens NFTS: (Crypto, Cryptocurrency, Polkadot, Trading, Bitcoin, Staking, Earn Money Online, Invest, Ethereum, Blockchain, Defi, Oracle, Chainlink). 2021. Available online: https://pt.scribd.com/document/537515725/A-Guide-to-Crypto-Collectibles-and-Non-Fungible-Tokens-NFTS-Crypto-Cryptocurrency-Polkadot-Trading-Bitcoin-Staking-Earn-Money-Online-Invest-Ethereum-B (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Nowill, R. Is It Time to Invest in Virtual Fashion? Hype Beast. Available online: https://hypebeast.com/2021/1/virtual-ar-fashion-tribute-rtfkt-aglet (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Dukedom, C. The Nft Revolution-Crypto Art Edition: 2 in 1 Practical Guide for Beginners to Create, Buy and Sell Digital Artworks and Collectibles as Non-Fungible Tokens; Independently Published, 2021; Available online: https://books.google.com.sg/books/about/The_Nft_Revolution_Crypto_Art_Edition.html?id=HT5tzgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 15 November 2022).