Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought massive online activities and increased cybersecurity incidents and cybercrime. As a result of this, the cyber reputation of organisations has also received increased scrutiny and global attention. Due to increased cybercrime, reputation displaying a more important role within risk management frameworks both within public and private institutions is vital. This study identifies key factors in determining reputational damage to public and private sector institutions through cyberattacks. Researchers conducted an extensive review of the literature, which addresses factors relating to risk management of reputation post-cyber breach. The study identified 42 potential factors, which were then classified using the STAR model. This model is an organisational design framework and was suitable due to its alignment with organisations. A qualitative study using semi-structured and structured questions was conducted with purposively selected cybersecurity experts in both public and private sector institutions. Data obtained from the expert forum were analysed using thematic analysis, which revealed that a commonly accepted definition for cyber reputation was lacking despite the growing use of the term “online reputation”. In addition, the structured questions data were analysed using relative importance index rankings. The analysis results revealed significant factors in determining reputational damage due to cyberattacks, as well as highlighting reputation factor discrepancies between private and public institutions. Theoretically, this study contributes to the body of knowledge relating to cybersecurity of organisations. Practically, this research is expected to aid organisations to properly position themselves to meet cyber incidents and become more competitive in the post-COVID-19 era.

1. Introduction

The reliance on cyberspace in contemporary societies and businesses has grown exponentially [1]. While technology has provided many advantages for organisations to develop and improve their operations, there are also disadvantages to the haphazard deployment of computer and networking technologies [2]. One prominent disadvantage is that inadequate security and business processes can result in significant financial loss to the organisation both materially and immaterially. Although direct financial losses through cyberattacks are often quantifiable, immaterial losses to organisational sentiment, goodwill, and reputation are not. This shadow pricing, a monetary value assigned to currently unknowable costs in the absence of correct market prices, can profoundly impact organisational competitiveness socio-economically. Organisations are also exposed to several cyber risks, including payment diversion fraud, ransomware, data breach, advanced persistent attacks, cyber theft, computer security breaches, cyber espionage, and even cyber terrorism [3,4]. Consumers hold the security of their personally identifiable data and other confidential information in high regard, and the protection of user privacy and data is integral to the continuation of consumer confidence [5]. As organisations view success as financial and material gain, reputation is an important component to manage in ensuring this. Reputation is an intangible asset that affects all stakeholders of an organisation. A myriad of factors can affect reputation, consumer confidence in the organisation, investor confidence, and their perception of the organisation as a respectable and trustable entity [6].

Cyberattacks are increasing at an alarming rate, and the cost of these attacks is increasing every year. In addition, the global pandemic has changed the operations of organisations and, as a result, the attack and risk profiles of the organisations [7]. As technology evolves, attacks increase in severity, with the most damage affecting corporate reputation and branding. Unfortunately, most public and private organisations are unaware and unprepared for the effects of these cyber risks. For instance, KPMG surveyed 1000 businesses in the UK and found that a cyber breach can significantly impact their reputation [8]. Over 58% of the companies surveyed underestimated the true impact that a breach can have on their company. Also, 599 businesses who had experienced a breach reported that breaches affected their reputation.

Responding to cyberattacks, including a comprehensive framework to protect and organise reputation, is critical for organisations. Cyberattacks can taint an organisation’s reputation and render them less competitive. However, there are no studies to date that critically consider factors that contribute to reputational damages suffered from cyber incidents within public and private sector organisations. Further, despite the significant efforts by researchers, there is yet to be publicly available research on reputation damage due to cyber risk within public and private sector organisations.

As an attempt to fill this gap, this study stands out, being the first to identify key factors in determining reputational damage to public and private sector institutions through cyberattacks. This study contributes to knowledge by presenting a master list of verified factors affecting the reputation of both public and private sector organisations through cyberattacks. In practical terms, the findings are expected to help organisations properly position themselves to become more competitive in the post-COVID-19 era. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reflects on relevant organisational reputation literature. The methodology adopted for this study is presented in Section 3. Section 4 presents the results and discusses the key factors in determining reputational damage to public and private sector institutions through cyberattacks. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Reputation of Organisations

“It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it”(Warren Buffett).

Broadly, reputation is viewed as the core of organisational value. Good corporate reputation is a valuable, intangible, scarce resource that is difficult to imitate [9,10,11]. Many studies have noted the significance of reputation to corporate value. Thus, investments in the creation of a positive reputation result in significant returns to the organisation [12,13]. Typically, the definition of corporate reputation brings together a concept of the multidimensional social construct, which involves the aggregation of perceptions of the stakeholders of the firm. These perceptions include the firm’s financial and non-financial aspects [14]. It is worthy to note that reputation can vary depending on the different stakeholder groups of the organisation [15].

Fombrun and Van Riel [16] defined reputation as a collective representation of a firm’s past actions and results that describes the firm’s ability to deliver valued outcomes to multiple stakeholders. Barnett, Jermier, and Lafferty [17] defined reputation as “observers’ collective judgments of a corporation based on assessments of the financial, social, and environmental impacts attributed to the corporation over time”. Hendrikx, Bubendorfer, and Chard [18] defined reputation as the perception an agent creates through past actions about its intentions and norms. Lange, Lee, and Dai [19] conceptualised reputation as being known, being known for something, and generalised favourability. The authors stated that available studies hinged on the assertion that reputation exists in the minds of beholders, as proposed by Fombrun [14]. For this study, we will adopt the definition of reputation by Dyer Jr and Whetten [20] as to how outsiders perceive an organisation, including the combined stakeholders’ assumptions and information about the organisation.

Several characteristics define the reputation of an organisation. These include financial performance [21,22,23], emotional appeal, products and services, vision and leadership, workplace environment, and social responsibility [21]; high-status affiliations [19], ownership, intensity and diversification of advertisements, specialisation, organisational age, longevity and past performance, market action profile, corporate culture, and identity [19,23]. The reputation of an organisation can be measured using surveys or questionnaires (reputation as general knowledge or beliefs), interviews (reputation as personality or brand knowledge and beliefs), or external rankings (reputation as evaluative judgement), brand equity (reputation as a financial asset) [19,24]. However, existing gaps in the literature call for further research on the reputation of organisations [23]. Table 1 presents a list of factors that affect the reputation of organisations available in the literature.

Table 1.

Factors affecting the reputation of organisations.

2.2. Cyber Reputation of Organisations

Recently, cybercrimes have been reported globally across several institutions. Over 20 serious cyberattacks occur daily [58]. A typical example is the case of Wannacry [59]. A single cyberattack can cause harm to several individuals, public, and private institutions [60]. Currently, the threat environment is growing at an alarming rate due to technological dependences. The emergence of cyberspace has given rise to novel strategic possibilities and threats resulting in a scramble to secure dominant positions [61]. Cyber reputation is crucial for building organisations’ competitive advantage in the private sector and essential for ensuring trust both within the public and private sectors.

Available studies have seen a growing use of the term “online reputation”. Barnett, Jermier, and Lafferty [17] defined online reputation by considering three areas: opinions and beliefs of stakeholders, intangible financial resources, and extensive knowledge of the institution. Dijkmans, Kerkhof, and Beukeboom [62] defined cyber reputation management as “the process of positioning, monitoring, measuring, talking, and listening as the organisation engages in a transparent and ethical dialogue with its various online stakeholders”. Other researchers have also focussed on different aspects of cyberspace. Anderson et al. [63] studied the costs of cybercrime for the UK economy using secondary data. The study estimated costs for cybercrime activities that had available data, mostly frauds, and excluded computer-integrity crimes. Klahr et al. [64] conducted an annual cybersecurity breaches survey for the UK government to build on the nationwide information security breaches survey that had been carried out repeatedly since 2004. The study reported that under half of the businesses suffered at least one cybersecurity breach. Paoli, Visschers, and Verstraete [60] studied the impact of cybercrime on businesses by presenting a conceptual framework and its application to Belgium. Kilinc and Cagal [65] proposed a reputation-based trust centre model to discover malicious and deficient information resources in addition to malicious information for cybersecurity services. The study also established a deterrent structure using simple mathematical methods to illustrate the effects of reputation computation. Kamiya et al. [66] developed and tested a model where a firm has an optimal exposure to cyber risk. The study established that reputation costs grow as sales growth and credit ratings drop if firms experience cyberattacks. Further, a firm’s industry competitors benefit from the attack if there is only idiosyncratic information about the target.

The emergence of the global pandemic—COVID-19 and its associated variants—has increased online activities across organisations. This has resulted in an upsurge in cyber incidents. As a result, researchers have recognised the need to focus on the reputation of organisations due to the emergence of cyber incidents. However, a unanimous definition is lacking, due to its interdisciplinary nature [67]. There is, therefore, the need to identify a common or generic definition for the cyber reputation of organisations.

2.3. Risk Management Frameworks for Cyber

The Institute of Cyber Risk Management [68] defined cyber risk as the financial loss or reputational damage that results from the failure of IT systems in an organisation. In 2017, the global economy lost around $600 billion due to cybercrime [69]. According to the IBM security report, in 2020 a company is likely to lose on average $3.92 MM per breach once a data breach occurs [70]. Cyber risks keep changing due to the continuous innovation, increasing use of internet-enabled devices, and the sophistication of cyber hackers. Organisations have become more vulnerable due to the exponential increase in IT-based systems and devices. Most often, both public and private institutions are usually the target of these cybercriminals. Although the Ponemon Institute reports on data breaches annually, limited empirical data are published on cyber risks. For example, a UK government report indicated that more than 50% of businesses had not identified their cybersecurity breaches [71].

There have been several frameworks for managing cyber risks. These frameworks include FAIR (Factor Analysis of Information Risk), NIST SP800 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Special Edition), CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System), TARA (Threat Agent Risk Assessment), OCTAVE (Operationally Critical Threat, Asset, and Vulnerability Evaluation), and CORAS. The FAIR institute outlines the need for organisations to switch from basic compliance and security measures into a more mature operational and risk-based reactive framework. The FAIR framework utilises risk factors taxonomy to calculate their frequency (likelihood) and impact (magnitude) [72]. Another framework is the NIST SP800, which focusses on barriers to cyber threats. The NIST framework can be utilised in identifying different barriers for different threats [73,74]. The CVSS framework presents a score for a cyber vulnerability based on its characteristics. These characteristics include the impact of the cyberattack [75]. The TARA framework scores cyber threats and selects the most significant threats for mitigation [76]. Another essential framework is OCTAVE, which identifies assets in risk and the threats as well the vulnerabilities that propel the occurrence of these threats [77]. Finally, CORAS is a security risk analysis method that utilises a model-based approach to identify threats and vulnerabilities [78]. Table 2 presents a list of prevalent cyber risk management frameworks identified in the literature. It is not intended to be a comprehensive list of all risk frameworks.

Table 2.

Risk management frameworks for cyber incidents.

2.4. Related Works on Reputational Risk

Many studies have discussed the hidden factors of reputation risk within enterprise risk management [79,80,81]. For example, in a 2006 study by de Bie, the author focussed on reputation damage within the private sector. In addition, the FAIR Institute has commented on reputation damage in the private sector as measurable by factors and stakeholders: consumers (decline in sales or market share), investors (stock price decline), lenders (increase in capital cost), regulators (business limitations), and employees (increased costs for attracting and retaining talent) [82].

Researchers at Oxford have produced a taxonomy of organisational cyber harm: physical or digital harm, economic harm, psychological harm, social and societal harm, and reputation harm [40]. Reputational harm was further broken down into damaged public perception, reduced corporate goodwill, damaged relationship with suppliers, reduced business opportunities, inability to recruit desired staff, media scrutiny, loss of key staff, loss or suspension of accreditations or certifications, and reduced credit scores. Finally, while not in the cyber context, a body of literature examines perception measures of reputation damage during product-harm crises [40,83].

Kim, Gurman, and Min [83] looked at perceptions of an organisation during and after product-harm crises, addressing: open and transparent, sincere and trustworthy, perceived ethical behaviour pre-event, supportive communication, resistance to negative information, and crisis resiliency. Lallie et al. [3] proposed a novel timeline of cyberattacks related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the significant efforts by researchers, there is yet to be publicly available research on reputation damage due to cyber risk within public and private sector organisations.

2.5. Classification Frameworks

Several classification frameworks were considered to ascertain the possibility of the factors affecting organisations’ reputations due to cyberattacks. These frameworks include the PESTEL (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal) framework, SWOT (strengths, weakness, opportunities, threats) framework, DEEPLIST (demographic, economic, environmental, political, legal, informational, social, and technological) framework, Porters 5 Forces, and STAR model. The PESTEL framework is a mnemonic used to compile macro-environmental factors to assist strategists in identifying the sources of risks and opportunities [84]. In addition, the framework analyses the external business environment to understand the ‘big picture’ in which organisations operate, enabling these organisations to take advantage of the opportunities whilst minimising the threats within the business environment [85].

Another framework is the SWOT, which aligns an organisation’s internal factors of capabilities, resources, and limitations to its external environment to begin the process of formulating strategies [86]. Managers of organisations can devise strategies by focussing on the relationships and interactions between the firm’s internal and external environment. The DEEPLIST is a framework that systematically analyses the emerging socio-economic environment [87]. This framework is considered a more holistic framework, since it integrates several dimensions in its analysis. Porters 5 forces present firms with the capability of achieving a competitive advantage and outperforming other industry players [88]. These forces include customers, suppliers, rivalry, substitutes, and new entrants in the job market. Porters 5 forces shape the market structure across every industry.

Finally, the STAR model is an organisational design framework where design policies fall into five categories [89]. These categories include strategy (direction of the organisation), structure (decision-making powers in the organisation), processes (information flow in the organisation), rewards (motivation for people to perform), and people (employees’ mindsets and skills). The STAR model was adopted for this study due to its specific alignment with organisations. Further, the STAR model serves as the backbone or foundation of the company that determines its design choices. The design policies are controlled by management and influence the behaviour of the employees. The model informs decision-making, influences behaviour, and ensures the effectiveness of the organisation. Further, for an organisation to be effective, all its policies need to be aligned and harmoniously interact with each other. The policy alignment will enhance effective communication and provide message consistency within the organisation. The STAR model has this advantage over other models and, therefore, was chosen for the study.

3. Research Methodology

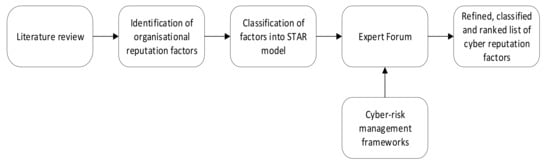

The research aim has been postulated by analysing the literature, the outcomes of a Delphi-based expert forum, in which both semi-structured and structured questions were asked, and their corresponding results. The methodology also follows a knowledge elicitation process where experts lead collective roundtable discussions and brainstorming [90,91,92]. The research approach is firmly based in the qualitative research paradigm, keeping in line with knowledge-based system development approaches. Here, knowledge of domain experts is captured through interactions with experts (in this case, by way of interviews). In this approach, the researchers are able to capture the factors identified through mapping to the STAR model and its relevance to cyber reputation of organisations. A critical review of the literature was conducted, and factors affecting the reputation of both public and private sector organisations through cyberattacks were identified. The literature reviewed provided a theoretical basis to underpin the study and laid the foundation for developing semi-structured and structured questions. In addition, a similar methodology as used by Opoku, Agyekum, and Ayarkwa [93] was used for the expert forum in this study. The research process adopted for the study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An overview of the research process used in the study.

There is an underlying assumption in the current literature that reputation analysis and impact will be the same in private and public institutions, but, as the research reveals, this is not the case. If, for example, a private institution suffers a cyber breach, one may be able to measure the loss of reputation through stock market prices or future access to equity markets. The same does not hold true with public institutions, especially those with no competition. The purpose of this study is to better tease out, through an expert group, the weighting to be given to factors influencing reputation, where they overlap between private and public institutions, and where they differentiate. Future research will leverage the findings in this study to undertake social media sentiment analysis and propose more efficient means of shadow pricing in this space.

3.1. Identification and Classification of Organisational Reputation Factors

The study utilised several academic databases, such as Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar, in retrieving publications relevant to the study. In addition, other web-based and industry reports on reputational damage to organisations were consulted. A critical review of the identified literature resulted in the identification of 42 factors that affect the reputation of organisations (see Table 1). These 42 organisational reputation factors were then classified under the STAR model framework. This model was suitable due to its alignment with organisations. The factors were further refined through expert reviews. The experts were guided by the cyber risk management frameworks in refining the factors classified in the STAR model framework. It is noteworthy to know that the expert reviews were based on industry experience of the experts.

Before the expert forum was conducted, a two-step piloting procedure was utilised to determine its appropriateness for the intended purpose. In the first step, the factors were reviewed by a distinguished professor who had over 10 years of experience in cyber risk management, ensuring that it was free from ambiguity and appropriate in technicalities. In the second part of the piloting, the factors were again reviewed by experts of different backgrounds who had experience in cyber risk management. They were also required to check the suitability and appropriateness of the classifications of the identified factors into the STAR model. They gave some constructive and encouraging feedback, which resulted in the merging of some factors. Similar piloting had been used in other equally important literature and cyber-related studies [44,94]. Following this feedback, the questions were finalised and administered during the conduct of the expert forum.

3.2. Expert Forum

3.2.1. Selection of Experts

A knowledge elicitation process where experts lead collective roundtable discussions and brainstorming [90,91,92] was employed in this study. Considering the nature of information that was required from the expert forum, well-experienced and knowledgeable experts in cybersecurity were needed for the forum. A purposive sampling was conducted using predefined criteria to select the potential experts. The selection criteria were as follows: (1) experts should be knowledgeable in cyberattacks in public and private sector organisations, (2) experts must be willing to be involved in the study, and (3) experts must hold a senior management position in his/her organisation [95]. In total, six experts from both public and private sector organisations were identified for the study. The experts comprised one Chief Information and Digital Officer (CIDO), one Director of Quality and Risk, one Director of Security Policy, Risk Management, and Cybersecurity Influence, one Chief Information Security Officer, one Principal Cybersecurity Consultant, and one Senior Cybersecurity Architect. The low number of experts was due to the fact that most of the senior officers declined the expert forum invitation based on other commitments that they had. It was also because of the selection criteria that were set. It is acknowledged that the number of experts was relatively small and that it may limit the generalisability of the research findings. However, it is not unusual for qualitative research (i.e., expert forum) to utilise few experts, since researchers seek to obtain rich data [96]. For example, Javed, Lam, and Chan [97], in a research work dubbed “A model framework of output specifications for hospital Public Private Partnership and Private Finance Initiative projects”, interviewed only two experts. Notwithstanding, the experience of experts (some of them had close to 15 to 20 years’ experience as well as working across both public and private institutions) enhanced the genuineness of responses for further analysis. Further, out of the six experts involved in the study, four had extensive knowledge of cyberattacks in both public and private sectors, and two had extensive knowledge of cyberattacks in the private sector only.

3.2.2. Design of Expert Forum Questions

The expert forum was conducted with experienced cybersecurity experts in both public and private institutions. The expert forum was carried out between February 2021 and March 2021. The study adopted the expert forum to be able to examine the problem critically (O’Connor & Norton 2020). To add to this, Soss [98] indicated that expert forums give a vivid explanation of a phenomenon. More so, the qualitative technique was adopted to gain a holistic and extensive understanding of the issue of the cyber reputation of organisations. In structuring the questions for the expert forum, both semi-structured and structured questions were developed. The semi-structured questions were: (1) How do you define cyber reputation and use terminology other than cyber reputation? (2) What cyber risk management models do you use, and do they incorporate reputation? (3) What types of cyber incidents do you model for? (4) Do you measure cyber reputation loss and, if so, how? For the structured questions, the identified 42 organisational factors were classified into the STAR model framework. A five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, and 5 = extremely important) was then used for prioritising the identified key factors. With these questions, the knowledge of factors affecting the cyber reputation of organisations is explored from the public and private sectors’ perspectives.

3.2.3. Conduct of Expert Forum

The expert forum instrument was pretested to correct errors during the online forum session and ensure the quality of information given. The forums were conducted in a relaxed manner through Zoom (online) and were recorded with the experts’ consent. The total time used for every forum ranged from 45 to 60 min. The experts were required to respond to the semi-structured and structured questions during the forum. Being guided by the risk management frameworks being used for cyber, the experts were required to refine and classify the list of factors affecting the reputation of organisations due to cyberattacks.

Further, experts were required to prioritise and build consensus on the identified factors using the five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, and 5 = extremely important). The qualitative data were transcribed and analysed using the thematic analysis technique. Thematic analysis is used in the study to identify, analyse, and report patterns or themes within data. It also allowed the researchers considerable freedom to interpret and select themes from the expert forum transcripts [93]. The qualitative responses to the expert forum were coded using NVivo 12 analysis application software. The coding involved examining experts’ responses to group and tagging the responses with codes to facilitate later retrieval. Verbatim transcripts were broken up into themes and classifications and then further utilised to break down the information within the expert forum [96]. This allowed the researchers to gather related material in one place to look for emerging patterns and ideas. The structured questions data were also analysed using IBM SPSS v27. In addition to the data’s descriptive (i.e., mean, standard deviation, and standard error) analysis, relative importance index rankings were also conducted on the data. Table 3 shows the detailed background of experts. For the purpose of anonymity, the names of experts are represented with codes: C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, and C6.

Table 3.

Profile of the experts.

4. Results and Discussion

The expert forum findings and discussions are presented in the following subsections. The discussions begin with the respondents’ background information and then focus on the objectives and broad areas of the study.

4.1. Profile of the Experts

From Table 3, it is seen that all participants are cybersecurity experts who have been involved in cyber risk management in both public and private organisations. The respondents’ experiences also indicate the in-depth knowledge and the participation level they have in managing cyber reputation in organisations. Moreover, the experts were willing to take part in the research. This is an indication that there was quality and adequacy in the information given, hence reliable for analysis.

4.2. Cyber Reputation of Organisations

The views of the respondents regarding cyber reputation of organisations are discussed in the subsequent sections:

- Definition of Cyber Reputation

- Risk Management Models for Reputation

- Modelling of Cyber Incidents

- Measuring Cyber Reputation Loss

4.2.1. Definition of Cyber Reputation

Although “online reputation” as a term has been used severally by researchers, no specific definition has been given to cyber reputation, especially among public and private sector organisations. A commonly accepted definition for online reputation is also lacking, even though there has been a growing use of this term [67]. Respondents were of the view that the definition of cyber reputation must always focus on the broad view of the external audience in terms of the cyber incidents of the organisation. This was evident in the experts’ comments. Expert C1 elaborated that:

“…the obvious one is the reputation that we (public institutions) might have for external audiences, and that could be within the sector, or it could be more broadly; and which tends to come from whether or not you (organisations) have had a cybersecurity incident. So, we (public institutions) have not had any publicly notifiable or particularly significant cybersecurity incidents in our organisation does not mean we (public institutions) have got a good reputation. It just basically means we (public institutions) have no reputation. So, the only reputation you tend to get is a negative one”.

In addition, Expert C5 stressed that:

“…it is a product of the competence an organisation has to manage its own security and privacy risks, as well as how proactively it contributes to the resilience and security of its customers, partners, and the broader ecosystem”.

Expert C4 also indicated that:

“…is the reputation for the company, usually on the angle of when a breach has occurred, the reputation what their clients or their customers view them. This is because their cyber reputation can be based on their security footprint or whether they have had a breach before, but, generally, the reputation as in security-wise, and how secure they keep everybody’s data”.

Expert C6 indicated that:

“…is essentially the confidence or trust that consumers or the general public have regarding an organisation’s ability to manage cyber risks, manage their information, and also provide reliable digital services”. Finally, “…is about continually projecting confidence in the of kind of capabilities that is being built up or just the sense that the organisation even cares and take cybersecurity seriously”(Experts C3 and C5).

Therefore, the definition of cyber reputation has to focus on the confidence built in the external audience relating to cyber issues. Notwithstanding, most respondents did not have different names for such a scenario apart from cyber reputation.

4.2.2. Risk Management Models for Reputation

Most organisations take reactive approaches to reputation management, focussing on risks that have already surfaced instead of the potential issues that may arise [99,100]. Some of these organisations assess their reputation using contextual objective measures. These could include analysing media reports, surveys of different stakeholders, and public opinion polls. Notwithstanding, the majority of organisations, both public and private sector, utilise well-known standard frameworks and models for managing the cyber reputation of their organisations. These standard models include the FAIR model and the NIST Cybersecurity framework. Schmoeller [101] identified a four-stage basic risk assessment methodology for FAIR to include identifying the scenario’s components, evaluating the loss event’s frequency, evaluating probable loss magnitude, and, finally, deriving and articulating the risk. Other organisations also align their risk management to the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy developed following ISO 31000 Risk Management Guidelines. This is evident in the experts’ comments. Expert C3 stressed that:

“…we (private organisations) aligned the risk management to the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy and developed it per ISO 31000 Risk Management Guidelines. The impact on brand and reputation is considered within the Enterprise Risk Management Framework when assessing risks”.

Expert C1 indicated that:

“… we (public organisations) tend to focus on the ISO standards and the essential eight requirements of dealing with cybersecurity-related matters. In addition, we (public organisations) also focus on the NIST framework”. “We have also piloted the FAIR model to provide further data-driven and high-quality security risk assessments that provide a quantitative view of reputation loss”(Experts C2 and C6).

4.2.3. Modelling of Cyber Incidents

Among the respondents from public and private sector organisations, the majority modelled for data breaches and other cyber incidents, such as ransomware, denial of service attacks, and website attacks. This is quite understandable, because previous studies, including Snider et al. [102] and Whitler and Farris [41], have mentioned that data breaches are a common and significant form of cyber incidents. The authors stated that companies such as Yahoo and Target were required to invest upwards of hundreds of millions of dollars in the event of a data breach. Further, the Target breach affected their “Buzz score”, dropping by 35 points after the breach was confirmed. For this reason, most organisations tend to model for data breaches. Expert C3 elaborated that:

“Since the threat environment is constantly changing, we evolve our modelling to match the current threats. In addition, we (private organisations) take an over-the-horizon view through the insights provided by our Security Intelligence Centre and relationships with Government agencies and the broader intelligence sharing community to be tuned to the threat landscape. Beyond modelling, we (private organisations) also actively simulate events such as data breaches or ransomware incidents to ensure teams are prepared to respond to the threats facing organisations daily”.

Experts C1, C4, and C6 also stated that

“…we (public organisations) do not exclude any cyber incidents. However, we tend to focus predominantly on data breaches, phishing, and fraud. Therefore, the business email compromise is certainly a vector that is most commonly tried within organisations, and a lot of our mandatory cybersecurity training has room centred on that particular aspect, but, still, fraud is also something we (public organisations) are conscious of”.

4.2.4. Measuring Cyber Reputation Loss

Significant cyber reputational losses occur when the media publicise incidents. The severity of media-related reputation losses is dependent on the type of media, incident timing factors, recurrence of incidents, and extent and nature of the incident [37]. Thus, these factors significantly affect the public image of these organisations once they occur. For this reason, organisations are eager to identify and measure their cyber reputational losses. However, the majority of organisations do not directly measure cyber reputation loss. This is evident from Expert C2 that:

“…we (private organisations) have not seen it measured in any quantitative way. In most organisations, it is articulated in terms of the impact of the reputational loss. We know it can affect us financially in terms of lost revenue and share market impact. We (private organisations) have seen it badly handled and rapid media response to reputational issues translating to big share price drops. It can affect us if we manage our reputation poorly. We will get more attention from a regulator or the government. Therefore, we will get the knock on the door from the Privacy Commissioner, because it is now a big deal. Equifax was a good example where they ended up having senate and congressional inquiries because the whole thing just sprawled and spiralled out of control”.

Expert C3 also stated that:

“… we (private organisations) indirectly measure reputation loss through understanding the market we (private organisations) are serving and how a change in their beliefs about the cyber reputation of the organisation would impact us. Areas such as media sentiment are actively monitored by our Corporate Affairs team, with it being one of the potential indicators of reputation loss”.

However, Expert C5 indicated that:

“…so, we (public organisations) more broadly, in terms of our risk management approach and the criticality of risks, we put a $1 value as a way to determine whether a risk is a moderate risk, a critical risk, or a catastrophic risk. So, but there are also some qualitative measures within that broader risk matrix”.

Therefore, it can be deduced that most organisations do not have a direct means of measuring cyber reputational losses within their organisations.

4.3. Factors Affecting Cyber Reputation of Organisations

The findings from the expert forum are summarised in descriptive statistics, and these are shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8. Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 present the five-point Likert scale that has been converted into relative importance indices (RII) using the relative index ranking technique [94]. It uses the priorities identified by the respondents for the factors affecting cyber reputation of organisations. The RII was calculated using the following equation: RII = ∑ W/A × N, where ∑ is the total frequency in the sample, W is the weighting given to each factor by respondents, ranging from 1 to 5, A is the highest weight (which is 5 in this case), and N is the total number of respondents involved in the study. From the equation, the values obtained for the RII range from 0 to 1. The relative importance of the factors is demonstrated in the various classifications under the STAR model in the subsequent sections. These classifications are listed to include:

Table 4.

Classification under strategy.

Table 5.

Classification under structure.

Table 6.

Classification under process.

Table 7.

Classification under rewards.

Table 8.

Classification under people.

- Classification under Strategy

- Classification under Structure

- Classification under Process

- Classification under Rewards

- Classification under People

4.3.1. Classification under Strategy

Table 4 shows the results of the descriptive analysis as well as the results of other relevant statistical tests for the classification under strategy. The mean scores of the importance of the factors range from 1.60 to 4.80. Notably, the mean scores of the majority (76.9%) of the factors under this classification were much higher than 3.00, which is the median value of the rating scale. This implies that the factors had significant importance. This could be attributed to the desire of both public and private organisations to effectively manage their organisations’ reputations resulting from cyber incidents [2]. Due to this quest, factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations have become a necessity rather than an option for these organisations. Although most of these factors were important, ranking them would enable organisations and stakeholders to understand which factors are worth more attention. Thus, prioritising the factors that fall under the classification under strategy.

Based on the results, the top three factors (mean ≥ 4.25) were “customer trust and confidentiality”, “customer perception”, and “public dissemination of incident”. The results indicate that these factors were considered the most important factors under the classification under strategy and, therefore, should attract organisations’ and their stakeholders’ attention. The three factors are discussed below, along with the factor “stock market price”, as the relatively low rank of this factor seems surprising.

“Customer trust and confidentiality” was ranked first with the highest relative importance index and mean score (RII = 1.00, mean = 4.80). This result indicates that customer trust and confidentiality were considered the most important factor that affects the organisation’s reputation resulting from cyber incidents. The importance of this factor was also supported by de Bie [37] and Khojastehpour and Johns [36], where the confidentiality and trust of customers affect the reputation of the organisation. The customers’ trust in the organisation can impact the reputation of the organisation. For instance, in the case of Sony, the confidential data from Sony Pictures were leaked, and this affected the trust of their customers, giving them a bad reputation [40]. The company had to also provide psychological counselling for its employees and, again, organise seminars on data security.

The factor “customer perception” was ranked second (RII = 0.90, mean = 4.40). The role of customers’ perception in affecting the cyber reputation of organisations cannot be underrated. Dutot and Castellano [25] indicate that reputation is based on perceptions, since the Internet does not distinguish between official information and subjective interpretations of the organisation’s customers. A bad reputation can result from their customers’ perceptions, since they cannot fully control their reputation offline, and this is even more difficult online. Therefore, organisations need to prioritise their customers’ perceptions to have a positive picture and a good reputation. This may perhaps explain why “customer perception” was ranked as the second most important factor affecting the cyber reputation of organisations under the classification of strategy.

The factor “public dissemination of incident” occupied the third position (RII = 0.80, mean = 4.25). This result indicates that disseminating the cyber incident to the public is critical in affecting the organisation’s reputation. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies [25,44]. According to Pomering and Johnson [103], the communication strategies adopted by the organisation affect its reputation. If organisations cannot properly manage the sharing of the cyber incident to the public, this can significantly affect the organisation negatively. Thus, the concept of the reputation of these organisations is more vital in the cyber world [104]. For instance, in the attack on UK Internet service provider TalkTalk in 2015, their customers were upset with how the company communicated and responded to the attack, which affected their reputation. In addition, in the case of the Equifax data breach, the delay in communicating the breach to the public resulted in an upset among the public, affecting their reputation.

Perhaps the most surprising feature of the results is the relatively low rank of the factor “stock market price” (ranked 13). It is of no surprise that public institutions would not rank stock market price as important, as this is irrelevant to them. What was more curious, however, was that market factors were not scored in the top three for private institutions either. There is some evidence supporting that stock market price is a crucial factor affecting the cyber reputation of organisations [25,38,40,46,66,105]. To a large extent, this has been because the stock market price affects the organisation’s reputation. For instance, in the case of Yahoo, which is now known as Altaba, the Securities and Exchange Commission fined the company ($35 million) for failing to disclose known data breaches, and this affected its reputation. Further, in the case of the Equifax data breach, their share price dropped more than 30% after the disclosure of the breach amidst public criticisms, which, in turn, affected Equifax’s cyber reputation.

The ranking of trust and confidence over customers’ perceptions is somewhat of a surprise, demonstrating a deep commitment to true security and not merely false perceptions or merely public relations factors.

4.3.2. Classification under Structure

Table 5 presents the results of the factors affecting the organisation’s cyber reputation which were classified under structure. The mean scores of the importance of the factors range from 1.80 to 4.80. It is also noteworthy that the mean scores of the majority (60%) of the factors under this classification were much higher than 3.00, which is the median value of the rating scale. This suggests that the factors could affect the reputation of organisations as a result of cyber incidents.

Based on the ranking, the three most important factors (mean ≥ 4.40) under this classification were “security effectiveness”, “management and leadership”, and “regulatory risks”. From Table 5, it is seen that “security effectiveness” was ranked first, with the highest relative importance index and mean score (RII = 1.00, mean = 4.80). This result indicates that security effectiveness was considered the most important factor affecting organisations’ reputations resulting from cyber incidents. Inadequate cybersecurity can result in significant financial loss to organisations. This affirms Poremba’s [5] assertion that customers hold the security of their personally identifiable data and other confidential information in high regard. So, effective security of the customers’ data can boost their confidence in the organisation. Likewise, if there is poor security of customers’ data resulting in a data breach, this can give the organisation a bad reputation [6,55].

The factor “management and leadership” received the second position (RII = 0.90, mean = 4.40). Management and leadership are very significant factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations. This result is in line with Sandu [30] and Rhee and Valdez [23], who pointed out that efficient management and leadership can preserve the organisation’s good reputation. For instance, organisations are likely to avoid some of these cyber incidents with good cybersecurity measures in place. Therefore, efficient management and leadership of the organisation can prevent cyber incidents resulting in a bad reputation. The findings infer that customers and other stakeholders will like to see organisations with good management and leadership to avoid these cyber incidents, such as data breaches and ransomware, in their organisations.

Similarly, “regulatory risks” obtained a RII = 0.90 and mean = 4.40, but, because its SD (0.894) was higher than the SD of the factor “management and leadership”, it was ranked third. Regulations are critical to the success of any organisation. This finding concurs with Pérez-Cornejo, de Quevedo-Puente, and Delgado-García [39], who stated that regulatory and business risks could affect the reputation of organisations. The risks associated with business regulations can significantly affect an organisation’s reputation. In line with this, reduced regulatory concerns can affect the cyber reputation of organisations [25].

Financial performance was also rated surprisingly low for structural factors. Again, this is also consistent with the low ranking of economic factors such as stock market price, as seen under strategy. This could be explained by the inclusion of public sector views; the fact that CEOs and Chief Financial Officers were not interviewed (it stands to reason that there would be a bias from those in the technology and security side of a business); and/or that society is moving towards trust becoming an essential element of business, both private and public. This last point again supports the importance of trust and confidentiality (strategy) and security effectiveness (structure) as indicated by participants.

4.3.3. Classification under Process

Table 6 presents the results of the factors affecting the organisation’s cyber reputation which were classified under process. The mean scores of the importance of the factors range from 3.10 to 4.80. Thus, all the mean scores of the factors classified under process were much higher than 3.00, which is the median value of the rating scale. This implies that all the factors had significant importance.

From the results, the top three factors (mean ≥ 4.40) were “cyberattacks and incidents”, “internal coordination and controls”, and “stakeholder response speed”. The results indicate that these factors were considered the most important factors under the classification under process and, therefore, should attract organisations’ and their stakeholders’ attention.

“Cyberattacks and incidents” was ranked first, with the highest relative importance index and mean score (RII = 1.00, mean = 4.80). This result represents that cyberattacks and incidents significantly affect the reputation of organisations. The importance of this factor was also supported by Wilding [106], Agrafiotis et al. [40], Pérez-Cornejo, de Quevedo-Puente, and Delgado-García [39], Alva [48], de Bie [37], and Whitler and Farris [41], where cyberattacks and incidents were an important factor affecting the reputation of organisations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to find this the most important factor contributing to an organisation’s reputation, both private and public institutions. Future studies would be required, however, to confirm this on scale. As cyberattacks and incidents have become a growing concern for organisations, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative for organisations to focus on both cybersecurity and cyber-resilience to maintain their reputation. Organisations must invest more in effective learning to educate on security awareness [106]. Thus, more knowledge on cyberattacks and incidents can minimise the possibility of these incidents occurring to damage the reputation of organisations.

The factor “internal coordination and controls” was ranked second under this classification (RII = 0.92, mean = 4.50). The internal coordination and controls in the organisation can significantly impact the reputation of the organisation. Organisations with more efficient internal controls are more likely to minimise the occurrence of cyber-related incidents. This can help prevent the organisation from getting a bad reputation once a cyber incident happens and becomes a piece of public knowledge. This factor emerged as a new factor for the study, since it was not identified in the literature.

The third factor under this classification was “stakeholder response speed”, with a relative importance index and mean score of 0.92 and 4.40, respectively. The speed with which stakeholders respond to a cyber-related incident in the organisation cannot be underrated. This can have a significant impact on the reputation of the organisation. Dutot and Castellano [25] also identified that stakeholder response speed as one of the top factors affecting organisations’ cyber reputations. Similarly, Herrmann, Brenner, and Stadler [58] and Piggin [107] agree that the response speed of stakeholders of the organisation is vital, because it impacts their confidence in the organisation. Therefore, it is worthy to consider the response speed of stakeholders once a cyber-related incident occurs, since that can have a significant impact on the organisation.

4.3.4. Classification under Rewards

Table 7 presents the results of the factors affecting the cyber reputation of an organisation which were classified under rewards. The mean scores of the importance of the factors range from 3.33 to 4.17. All the mean scores of the factors under this classification were much higher than 3.00, which is the middle value of the rating scale. This suggests that the factors are significant in affecting the cyber reputation of organisations.

Based on the ranking, the two most important factors (mean ≥ 3.83) under this classification were “emotional connections and responses” and “employee satisfaction”. From Table 6, it is seen that “emotional connections and responses” was ranked first, with the highest relative importance index and mean score (RII = 1.82, mean = 4.17). This result indicates that the emotional connections and responses in the organisation were considered the most important factor that affects its reputation as a result of cyber-related incidents. Many customers turn to focus more on their emotions, which can affect the perception of these customers on the reputation of the organisation. This finding concurs with Dutot and Castellano [25] and Bada and Nurse [42], who indicated that emotional connections can change how the public views organisations, affecting their reputation.

“Employee satisfaction” was ranked second, with a relative importance index and mean score (RII = 1.00, mean = 4.80). This result indicates that employees’ satisfaction was considered an important factor that affects the reputation of an organisation resulting from cyber incidents. From the finding, it is evident that once the employees are satisfied in the organisation, they will be willing to work harder to help prevent cyber-related incidents, which could damage the organisation’s reputation. This result confirms the study by Ismail, Mustapa, M., and Mustapa, F.D. [52], Radichel [108], and Sandu [30], indicating that good employee satisfaction will ensure that employees do not become insider threats to the organisation. An insider threat employee can damage the cyber reputation of the organisation.

4.3.5. Classification under People

Table 8 shows the results of the factors affecting the cyber reputation of organisations which were classified under people. The mean scores of the importance of the factors range from 3.00 to 4.17. It is interesting to note that all the mean scores of the factors classified under process were either 3.00 or greater, with 3.00 being the middle value of the rating scale. This suggests that all the factors had significant importance in affecting the cyber reputation of organisations under this classification.

Based on the results, the top two factors (mean ≥ 3.83) were “training and awareness programmes of organisations” and “sustained credibility”. The results indicate that these factors were considered the most important factors under the classification under people and, therefore, should attract organisations’ and their stakeholders’ attention.

The factor “training and awareness programmes of organisations” was ranked first under this classification (RII = 0.84, mean = 4.17). The role of training and awareness programmes of organisations in affecting cyber reputation of these organisations cannot be underestimated. The Ponemon Institute Report [38] reported that training and awareness programmes help keep employees updated with newer cyberattacks. It is not surprising that respondents rated this factor as the most important factor under this classification. For instance, in the Equifax breach, personal identifying data held by Equifax was hacked through publicised vulnerability in a web application. There were recommendations to have training and awareness programmes to enhance the knowledge on cyberattacks and incidents.

“Sustained credibility” was also ranked second under this classification (RII = 0.80, mean = 3.83). The credibility of organisations within the cyberspace is very important. Services are said to be more credible when organisations perform reliably for an extended period of time without issues. This finding affirms the studies by Zhu, Sun, and Leung [35] and Dutot and Castellano [25], who stated that sustained online credibility can determine how the public views that organisation. The organisation’s cyber reputation must be part of its global strategy to succeed.

4.4. Summary of Discussions

It was surprising to see that there was much consensus between private and public institutions’ evaluation of essential factors for reputation. While this consensus was through a qualitative analysis, the findings have confirmed previous studies [19,25,36,37,38,39] within reputation management of private institutions’ dealings with cyber breaches. Recent studies also confirm that cyber reputation is an essential issue to be considered in risk management, and organisations who fail to adequately consider the risks and respond appropriately when breached to manage reputation will be putting their businesses at risk.

As previously noted, the average data breach costs $4.4 MM in 2021, with a 10% increase from 2020 [109]. These estimates, however, are based on economic impacts of data breaches mainly focussed on: response costs, lost business, recovery, escalation, and notification. These estimates do not directly value cyber reputation damage, nor do they calculate aspects such as the cost to pay a ransom in ransomware or the loss of fraudulent payment. There is a growing consensus, as this study further demonstrates that cybersecurity reputation is considered essential to an organisation’s success.

Considerations related to trust, effective response, and leadership were ranked more highly for both private and public institutions than considerations with more direct association to obvious monetary values, such as stock market prices, loss of revenue, and financial performance. While the bottom economic line is important, the participants were consistent in their views that the effective long-term management and response to cybersecurity issues were key to managing the corporation’s overall reputation.

The Western Sydney University in Australia recently divided the CISO role into two roles—CISO Cybersecurity and CISO “All other”—for lack of a better word [110]. Organisations are increasingly seeing new roles such as CISO Cybersecurity and Cyber Risk Manager to manage cybersecurity threats in businesses [111]. This may be due in part to the rise in number of cybersecurity threats; economic, physical, and psychological harms caused by incidents; and a growing concern of trust with many organisations moving to a zero-trust environment [112]. Within cyber risk management, cyber reputation, and, with this, reputation affected by cyber-attacks, is becoming more critical to an organisation’s success [113].

For organisations looking to quantify and evaluate reputation risk, the process is fraught with challenges. The only easily quantifiable aspect is one related to money, such as loss of business, stock market prices, and financial performance, but most factors in reputation are not directly quantifiable. As such, shadow pricing strategies will need to be used. Successful shadow pricing strategies, however, rely on a way of prioritising factors or aspects to be measured. This study has made a first step in doing so by ranking factors as divided into five main areas relevant to organisations under the STAR model. This will allow shadow pricing models to put higher weights on certain reputation factors over others, leading to more efficient and accurate ways of measuring cyber reputation risk both for private and public sector institutions.

5. Conclusions and Future Research

Cyber reputation of organisations has recently received increased global attention. This is because of the massive online activities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated variants together with the restrictions and lockdowns. As a result, this study was conducted to identify key factors in determining reputational damage to public and private sector institutions caused by cyberattacks. A literature review and interviews with cybersecurity experts led to the identification of 42 potential factors, which were further classified into the STAR model, an organisational design framework. This study is novel, as it is one of the first to establish the factors that affect the cyber reputation of both public and private sector institutions. The findings are more relevant given the heightened cyber activities partly caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequent restrictions affecting organisational business activities.

The results of this study show that a commonly acceptable definition for cyber reputation is also lacking, even though there has been a growing use of the term “online reputation”. The results also show that, firstly, “customer trust and confidentiality”, “customer perception”, and “public dissemination of incident” were the top three factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations under the classification of strategy. Therefore, an organisation should develop and model communication strategies for different types of cyber incidents. Furthermore, controlling the narrative through an effective community engagement strategy is seen by all stakeholders as imperative.

Secondly, “security effectiveness”, “management and leadership”, and “regulatory risks” were also the top three factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations under the classification of structure. This demonstrates that regulatory risks may play a larger part in influencing organisations to adopt more security controls, along with the identification of effective security controls, all the while steered through positive management and leadership. This implies that cyberattacks are no longer seen to fall within the limited purview of the IT section of an organisation.

Thirdly, under the classification of process, “cyberattacks and incidents”, “internal coordination and controls”, and “stakeholder response speed” were the top three factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations. These findings indicate that an effective cyber incident response plan coupled with training exercises are essential to mitigate against damage of cyberattacks, including reputational damage.

Fourthly, “emotional connections and responses” and “employee satisfaction” were the top two factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations under the classification of rewards. Employee satisfaction is not one currently found in the existing literature. Implications from this finding, including emotional connection in response, indicate that employees should be trained in cyber awareness and preparedness not only to better secure the organisation but to make them feel that they are part of the solution and for an internal validation process.

Finally, the top two factors that affect organisations’ cyber reputation under the classification of people were “training and awareness programmes of organisations” and “sustained credibility”. Therefore, this study contributes to the body of knowledge relating to organisations’ cybersecurity by analysing the key factors affecting the reputation of organisations resulting from cyber incidents. Moreover, the findings of this study are expected to help organisations properly position themselves to meet cyber incidents and become more competitive in the post-COVID-19 era.

Notwithstanding the achievement of the objective, this study was not conducted without limitations. The first limitation is the importance assessment made in the study. This could be influenced by the respondents’ experiences as well as attitudes, since it was subjective. In addition, the study utilised qualitative methodology, somewhat limiting its generalisability. This study analysed only the views of selected cybersecurity experts on the factors; thus, future research could consider quantitative approaches targeting the whole population of relevant organisations. The limitations mentioned above generate fertile grounds for further research and should be considered when interpreting the findings of the research. This study recommends using a wider sample size and additional empirical factors that could broaden the understanding of the views of other risk management and cybersecurity experts. Nevertheless, the study is ground-breaking, as, for the first time, it brings to light a classified and ranked set of factors that affect the cyber reputation of organisations, while highlighting important differences between reputation management of private versus public institutions. Future studies will be able to utilize our ranked set of factors for reputation shadow pricing as well as to assist with social media sentiment analysis and how best to respond to reputation damage. This will pave the way for organisations to integrate cyber risks into management policies and procedures of organisations, enabling better governance of cyber threats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., X.J., A.M. and D.-G.J.O.; methodology, S.P. and D.-G.J.O.; software, S.P. and X.J.; validation, A.M., S.P. and X.J.; formal analysis, D.-G.J.O.; investigation, S.P., A.M. and D.-G.J.O.; resources, S.P., X.J. and A.M.; data curation, D.-G.J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-G.J.O.; writing—review and editing, S.P., X.J. and A.M.; visualization, S.P., X.J., A.M. and D.-G.J.O.; supervision, S.P., X.J. and A.M.; project administration, S.P., A.M. and X.J.; funding acquisition, S.P., X.J. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Western Sydney University through the Grant Assistance Scheme 2020 under the research champion Urban Living Futures and Society.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018), Australia, and approved by the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (H14086 and 9 November 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the forum experts for providing their opinions, which were incorporated in producing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arcuri, M.C.; Brogi, M.; Gandolfi, G. Cyber risk: A big challenge in developed and emerging markets. In Identity Theft: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 292–307. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, F.; Pusatli, O.T. Cyber attacks and preliminary steps in cyber security in national protection. In Cyber Security and Threats: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lallie, H.S.; Shepherd, L.A.; Nurse, J.R.; Erola, A.; Epiphaniou, G.; Maple, C.; Bellekens, X. Cyber security in the age of covid-19: A timeline and analysis of cyber-crime and cyber-attacks during the pandemic. Comput. Secur. 2021, 105, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; Hofmeyr, S.; Forrest, S. Hype and heavy tails: A closer look at data breaches. J. Cybersecur. 2016, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poremba, S. The Cyber-Risk Paradox: Benefits of New Technologies Bring Hidden Security Risks; Security Boulevard: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adeosun, L.P.K.; Ganiyu, R.A. Corporate reputation as a strategic asset. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- FireEye. M-Trends Report 2021; FireEye, Inc.: Milpitas, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Raineri, E.M.; Resig, J. Evaluating Self-Efficacy Pertaining to Cybersecurity for Small Businesses. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2020, 22, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bergh, D.D.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Boyd, B.K.; Bergh, J. New frontiers of the reputation—Performance relationship: Insights from multiple theories. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P. Reputation as an intangible asset: Reflections on theory and methods in two empirical studies of business school reputations. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.D.; White, L. Reputational contagion and optimal regulatory forbearance. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzert, N.; Schmit, J. Supporting strategic success through enterprise-wide reputation risk management. J. Risk Financ. 2016, 17, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelisi, F.; Soana, M.-G.; Schwizer, P. The determinants of reputational risk in the banking sector. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, K. A systematic review of the corporate reputation literature: Definition, measurement, and theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Van Riel, C. The reputational landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Jermier, J.M.; Lafferty, B.A. Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx, F.; Bubendorfer, K.; Chard, R. Reputation systems: A survey and taxonomy. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2015, 75, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.; Lee, P.M.; Dai, Y. Organizational reputation: A review. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G., Jr.; Whetten, D.A. Family firms and social responsibility: Preliminary evidence from the S&P 500. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 785–802. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.; Gardberg, N.A.; Sever, J.M. The Reputation Quotient SM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 7, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, M.; Valdez, M.E. Contextual factors surrounding reputation damage with potential implications for reputation repair. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clardy, A. Organizational reputation: Issues in conceptualization and measurement. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2012, 15, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutot, V.; Castellano, S. Designing a measurement scale for e-reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, M. Making Digital Cultures: Access, Interactivity, and Authenticity; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, D.; Eisenegger, M. CSR communication, corporate reputation, and the role of the news media as an agenda-setter in the digital age. Bus. Soc. 2020, 60, 1957–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Ruiz, L.; Castillo, A.; Llorens, J. How corporate social responsibility activities influence employer reputation: The role of social media capability. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 129, 113223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Siciliano, G.G.; Gaudenzi, B.; Eickhoff, M. Effects of data breaches from user-generated content: A corporate reputation analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, M.C. The factors responsible with corporate reputation: A structural equation modelling approach. Rom. J. Econ. 2015, 40, 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, K.; Yang, S.-U. The effect of bad reputation: The occurrence of crisis, corporate social responsibility, and perceptions of hypocrisy and attitudes toward a company. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Madariaga, J.; Rodríguez-Rivera, F. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, corporate reputation, and firms’ market value: Evidence from the automobile industry. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2017, 21, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox Pahnke, E.; McDonald, R.; Wang, D.; Hallen, B. Exposed: Venture capital, competitor ties, and entrepreneurial innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1334–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.-Y.; Leung, A.S. Corporate social responsibility, firm reputation, and firm performance: The role of ethical leadership. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Johns, R. The effect of environmental CSR issues on corporate/brand reputation and corporate profitability. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bie, C. Exploring Ways to Model Reputation Loss. Master’s Thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ponemon Institute. The Impact of Data Breaches on Reputation & Share Value. A Study of U.S. Marketers, IT Practitioners and Consumers; Ponemon Institute Report; Ponemon Institute: Traverse City, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cornejo, C.; de Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J.B. How to manage corporate reputation? The effect of enterprise risk management systems and audit committees on corporate reputation. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrafiotis, I.; Nurse, J.R.; Goldsmith, M.; Creese, S.; Upton, D. A taxonomy of cyber-harms: Defining the impacts of cyber-attacks and understanding how they propagate. J. Cybersecur. 2018, 4, tyy006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitler, K.A.; Farris, P.W. The impact of cyber attacks on brand image: Why proactive marketing expertise is needed for managing data breaches. J. Advert. Res. 2017, 57, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, M.; Nurse, J.R. The social and psychological impact of cyberattacks. In Emerging Cyber Threats and Cognitive Vulnerabilities; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, A.; Ghujali, T.; Bastam, H. The Effect of Organizational Reputation on E-loyalty: The Roles of E-trust and E-satisfaction. ASEAN Mark. J. 2019, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sabharwal, S.; Sharma, S. Ransomware Attack: India Issues Red Alert. In Emerging Technology in Modelling and Graphics; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni, G.; Grundy, B.; Zeng, Q. Stock returns and the Miller Modigliani valuation formula: Revisiting the Fama French analysis. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leippold, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, W. Machine learning in the Chinese stock market. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

- Di Maggio, M.; Egan, M.; Franzoni, F. The value of intermediation in the stock market. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

- Alva. Corporate Reputation. 2020. Available online: https://www.alva-group.com/blog/what-are-the-advantages-of-a-good-corporate-reputation/ (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Romanosky, S. Examining the costs and causes of cyber incidents. J. Cybersecur. 2016, 2, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaroch, M. Third-party induced cyber incidents—Much ado about nothing? J. Cybersecur. 2021, 7, tyab020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotnick, S.A. Lead-time quotation when customers are sensitive to reputation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.; Mustapa, M.; Mustapa, F.D. Risk factors of contractor’s corporate reputation. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Informatics, Beijing, China, 17–19 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Global Survey on Reputation Risk. 2015. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/za/Documents/risk/NEWReputationRiskSurveyReport_25FEB.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Liao, Z. Environmental policy instruments, environmental innovation and the reputation of enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, C.A. Do data breaches damage reputation? Evidence from 45 companies between 2002 and 2018. J. Cybersecur. 2021, 7, tyab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlastelica, T.; Kostic, S.C.; Okanovic, M.; Milosavljevic, M. How corporate social responsibility affects corporate reputation: Evidence from an emerging market. JEEMS J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2018, 23, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakić, T.V.; Mijatović, I.; Marinović, N. Key CSR initiatives in Serbia: A new concept with new challenges. In Key Initiatives in Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, A.; Brenner, W.; Stadler, R. Cyber security and data privacy. In Autonomous Driving; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]