5. Discussion

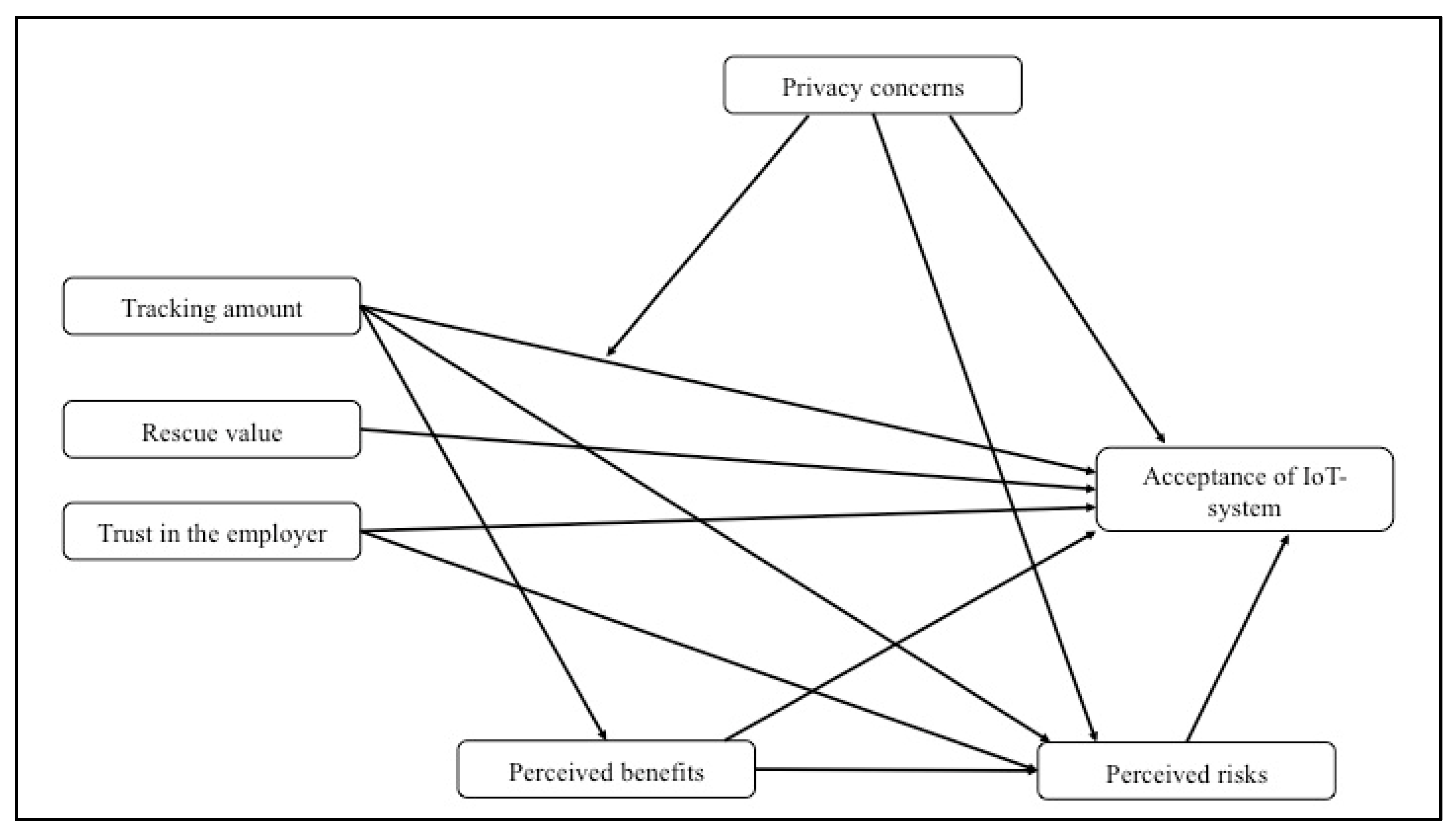

The current study examines employees’ acceptance of IoT technology at the workplace that is capable of data tracking. Therefore, we test whether trust in the employer, perceived privacy risks and anticipated benefits of the IoT system are related to its acceptance by juxtaposing privacy-preserving and privacy-invading approaches. Furthermore, we investigate the moderating effect of privacy concerns. Privacy calculus [

5] and CPM [

6] serve as the main theoretical foundations of this research.

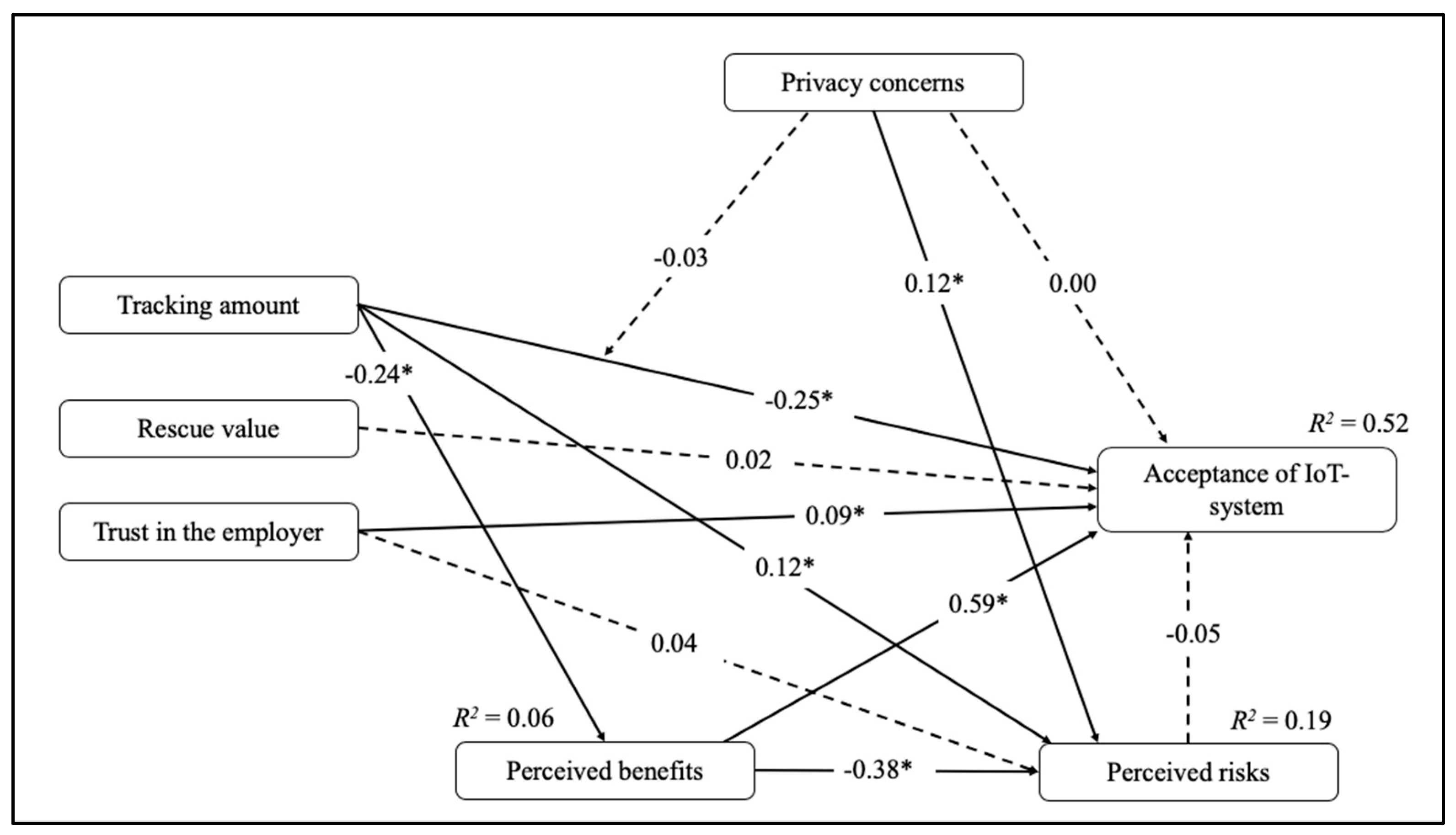

As suggested in the first hypothesis, trust in the employer is related to the acceptance of an IoT monitoring system deployed at the workplace. This means that employees who have a trusting relationship with their organization will more likely accept the deployment of an IoT system, even if the system is capable of collecting their personal data. Although it might seem plausible that employees pretend to accept new technology due to unbalanced power relations between management and staff the results of the path model demonstrate an explicit effect of trust on acceptance. The relationship between the level of trust in the employer and the level of IoT acceptance is highly significant. Therefore, we can assume that trust is a crucial factor of acceptance. This means that individuals who trust the employer will be more likely to accept the technology, while those who have less trust in the employer show lower acceptance—independent of the potential domination of the employer. These findings are in line with previous research stating that the willingness of individuals to provide private information is higher when they have a trusting relationship with their employer [

11].

Opposed to H2, however, the results show that trust in the employer does not lead to a lower perception of potential privacy risks. This could be due to the work-related context. At the workplace employees might expect more severe consequences when personal information is collected. Moreover, individuals might differentiate between their trust in the employer and their trust in the IoT technology, meaning that they believe in a confidential handling of their data by the employer but not by the system, possibly worrying about unlimited data collection and data forwarding. Consequently, the privacy risks that employees perceive with regard to a smart monitoring system might be high, despite the existence of a trusting relationship with the employer. This, again, emphasizes the importance of trust in the employer or the organization, as employees would accept a tracking system notwithstanding its privacy threatening potential as long as they trust their employer which might explain the missing relationship between trust and perceived risks. Recent studies [

8,

10] found that trust in a website positively influences the willingness to provide one’s personal data and therefore accept data collection. However, a substantial difference between data collection online and data tracking by an implemented IoT monitoring system is that on websites people voluntarily provide information actively indicating their data into various kinds of forms and entry fields. This visualization might contribute to the feeling of having control over collected data, while smart technology lacks transparency regarding purpose and amount of gathered information with perceived loss of control, which might lead to uncertainty and mistrust. At this point, communication with the employees plays a decisive role. Thomas et al. [

60] found that providing employees with relevant and adequate information has a positive effect on employees’ trust in supervisors and management. Accordingly, a deliberate communication strategy with employees might reduce potential negative consequences on commitment and trust when implementing the tracking system.

With regard to H3, it could be confirmed that the amount of tracking has an effect on the acceptance of IoT monitoring systems and on the perception of risks. Employees tend to accept a privacy-preserving IoT system that does not store data and omits identification of individuals rather than a privacy-invading IoT system with unlimited data collection and data forwarding. These results go in line with prior findings [

61] and give support to the information limit postulated by Sutanto et al. [

31]. Thus, people are rather willing to provide information to an IoT system, which, by its privacy-preserving approach, does not reach their information limit. Privacy-invading technology, on the other hand, can easily exceed the information limit with a low system acceptance as a consequence. The results also reinforce the CPM [

6] since privacy-preserving technology is reconcilable with the privacy management principles of this theory. In particular, this means that as long as employees’ privacy is not violated by IoT technology they can maintain their privacy rules and privacy boundary turbulences do not occur. On the contrary, when employees perceive their privacy being invaded by the monitoring system they might lose the feeling of control and possession of their private information resulting in a conflict regarding information disclosure and, therefore, a lower acceptance of a privacy-invading system. Additionally, the positive relationship between the amount of tracking and the perceived risks demonstrates that people connect IoT technology that is capable of collecting their data with privacy threat supporting results from previous studies [

32]. This means that even if employees cannot influence the deployment of IoT technology it is in the interest of the employer to protect the privacy of staff by implementing a privacy-preserving system in order to ensure employees’ acceptance and commitment.

Furthermore, the impact of the rescue value of the IoT system is investigated. Basing on the assumptions of privacy calculus theory [

5], the rescue value of the smart monitoring system represented one particular benefit of the deployment of the system since it immediately reacts when the sensors detect an emergency and directly contacts emergency forces in order to ensure the highest possible security of staff. Accordingly, H4 suggests that IoT technology with a high rescue value is related to a higher system acceptance as employees will put the perceived security provided by the system with a high rescue value over the perceived privacy threat. However, there is no relationship between the acceptance of the IoT system and its rescue value. One possible explanation is that employees already expect their workplace to provide a high level of security and do not see a particular benefit in the deployment of additional technology. Moreover, the rescue value of a smart monitoring system might be too abstract and theoretical to be perceived as a distinctive benefit of the system. Previous studies investigated more concrete or immediate benefits in the privacy calculus such as the free use of a website [

35] or convenience provided by IoT devices [

37]. Thus, the rescue value of a smart monitoring system might be perceived as less present compared to the privacy risks of the system, and therefore, less relevant in the risks-benefits trade-off. This assumption is substantiated by the fact that in this study benefits of the monitoring system were perceived rather low.

Regarding the impact of perceived benefits, it is shown that when people recognize the system as advantageous (e.g., in terms of a faster rescue in case of emergency) their acceptance of the IoT system is higher. A higher perception of risks, however, does not result in a lower acceptance of the system. This means that even individuals who believe the handling of the system with personal data to be problematic still accept this technology. This inference indicates that perceived benefits suppress the potential impact of perceived privacy risks. Consequently, employees are willing to accept monitoring technology as long as they evaluate these kinds of systems to be sufficiently beneficial, notwithstanding possible risks. It might be that, as employees’ possibilities for actions regarding the deployment of new technology are limited at the workplace they might feel forced to acquiesce IoT monitoring systems. In other words, if the organization decides to install the system, employees will either have to cope or quit their job. Therefore, it seems reasonable that employees would rather give their consent to collection of their data than losing their job. Additionally, as the data give evidence that individuals’ perception of the system’s privacy risks is high, another reason could be resignation. In this case, acceptance would be a result of a situation in which employees do not feel in control of the decision regarding technology deployment at the workplace due to unbalanced power-relations. Furthermore, legal restrictions of data tracking at the workplace might give reason to confidence, meaning that employees would accept new technology despite of the perceived privacy risks basing on their belief that their privacy is protected by jurisdiction.

Regarding H6, the data reveals that perceived benefits are negatively related to perceived risks. This means that when people perceive privacy risks as predominant they will see fewer benefits in the deployment of the system whereas when they mainly perceive the advantages of the technology they will rather perceive it to be less threatening in terms of privacy. This finding is of particular interest since it demonstrates that individuals do the risk-benefit trade-off even in situations, where their possibilities for actions are limited as it is the case at work. These results contribute to the privacy calculus research by supporting its applicability in the context of smart technology deployment. Just as people do the risk-benefit trade-off when deciding whether to disclose personal information online or not [

10,

17,

35,

36], they compare anticipated advantages and the possible privacy threat of IoT technology that is capable of tracking their data at the workplace. Thus, the privacy calculus takes place. However, in contrast to other situations in the work-related context the trade-off only leads to a behavioral intention when benefits are predominant.

In accordance with hypothesis H7, moderation effects were tested. The results did not support the assumption that privacy concerns moderated the relationship between the tracking amount and the acceptance of the IoT technology. Considering that extensive tracking of user data has become ubiquitous, people possibly perceive data collection as part of their everyday lives or the price they have to pay when using online services and smart devices. Thus, individuals might still worry about their privacy nonetheless accepting their data being tracked when their desire to use a particular device or service, such as smartphone navigation for example, exceeds the concerns regarding their privacy which in this case would be the tracking of their location [

61]. Since the study was conducted in a work-related context another reason might be the resignation of employees regarding their general privacy at work. The organization not only has person-specific information of staff at its disposal, but also the decisional power regarding the deployment of monitoring technology capable of data tracking. This means that the only two options left for the employees are to either tolerate the data collection notwithstanding their privacy concerns or to quit their job in order to evade being exposed to the frequent monitoring. This corroborates the findings of Wirth et al. [

62] who showed that resignation has a positive effect on the perception of benefits and a negative effect on the perception of risks. Consequently, when employees react to privacy threats with resignation, they might have an altered perception of risks and benefits explaining a higher acceptance of monitoring technology despite of possible privacy concerns. Moreover, it should be noted that the items from the privacy concerns scale were adapted to the workplace context and measured privacy concerns regarding the handling of personal data by the employer and not by the IoT system. With the CPM principles in mind, it is conceivable that individuals are able to apply privacy rules at work but at the same time experience privacy boundary turbulences caused by the deployment of the monitoring system meaning that employees are less worried about their privacy at work than about a third party in form of an external system getting access to their data. In this case, privacy concerns might moderate the relationship between the amount of tracking and the acceptance of the monitoring system when the privacy concerns scale refers to the system instead of the employer. However, there is an indirect effect of privacy concerns on system acceptance. People who are worried about their privacy might also have a higher perception of privacy risks, which according to the results are directly related to the system’s acceptance explaining the indirect effect.

Interestingly, privacy concerns are positively related to perceived risks (H9). Individuals who are worried about their privacy are also more sensitive regarding their perception of potential risks for their personal data. Consequently, implications which can be drawn for employers are: first, that it is in their interest to protect privacy of staff by limiting employee monitoring or deploying technology with the privacy-by-design approach. In other words, considering the privacy of the workforce before implementing an IoT system enables the employer to resort to a system already working in a privacy-preserving way by its technical implementation which, thus, is more likely to be accepted by the employees. This decision might be a confidence-building measure ensuring a responsible handling of employees’ data respecting their value of privacy. Second, if the decision is in favor of installing a system that does not automatically cover the privacy of the employees by virtue of its functioning, and thus, does not have a privacy-by-design approach, the employer nevertheless has certain possibilities of influencing the acceptance of the system. On the one hand, the employer could provide the employees with detailed information regarding purpose and reasons for collecting the data. On the other hand, the employer could emphasize the benefits, such as security, that the system brings to the employees. Any measures that help to increase the acceptance of the new technology in the company are fundamentally beneficial in order not to jeopardize trust, commitment and performance.

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations of the study must be noted. First, participants did not evaluate a real IoT system, but had to imagine a hypothetical situation where such a system is implemented at their workplace by reading descriptions of the monitoring technology. Such scenarios are functional by allowing to draw first conclusions as well as making comparisons between different conditions. However, it is important to note that the generalizability is reduced due to the artificial content of the presented vignettes. In order for the evaluation of these scenarios to be realistic, the vignettes of this study describe existing features of smart monitoring systems and provide employees with information they can access due to data protecting legislation, such as the GDPR. However, employees might react differently if their employer actually makes the decision to deploy such a system. For this reason, in further studies research needs to reflect on employees’ reactions and acceptance processes under real circumstances. Furthermore, concerning the different scenarios caution should be taken when interpreting the results as the descriptions were written based on existing system features; however, in order to create different conditions the features were isolated. Thus, the interaction of the tracking amount and the rescue value are only hypothetical. Caution should also be taken with regard to generalizability of IoT system acceptance. Due to the heterogeneity and various characteristics of IoT devices, IoT systems might be evaluated differently in terms of privacy, perceived risks and benefits. Another remark is the unequal gender distribution of women and men of about 70:30, which is worth considering in future studies. Furthermore, the online study could not measure real behavior, but only estimate to which degree participants would accept the technology. Therefore, future studies could measure physiological effects or changes in work performance of employees when being monitored at work. A methodological limitation, as mentioned in the discussion, is that privacy concerns were measured only with regard to the employer and not to the IoT system. In order to better understand employees’ evaluation of smart technology it would be beneficial to also include this measurement into research. Since this study examined IoT technology in a work-related context it would also be interesting to investigate how people interact with the same technology in their private homes compared to the workplace. When thinking about privacy, the awareness of data tracking might be also examined as a determinant of the usage of IoT. As results by Thomas et al. [

60] demonstrated that providing employees with information influences their trusting relationship to management and supervisors, awareness and knowledge of employees regarding IoT monitoring systems at the workplace should therefore be included in future investigations.