Bringing the Illusion of Reality Inside Museums—A Methodological Proposal for an Advanced Museology Using Holographic Showcases

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Virtual Museum in The Real Museum—Need for a Better Integration

1.2. The Box of Stories—A New Proposal towards an Improved Museology

2. Holography

2.1. Pepper’s Ghost and the Illusion of Reality

2.2. Pepper’s Ghosts in Museums Today—Some Examples of Use and Technological Solutions

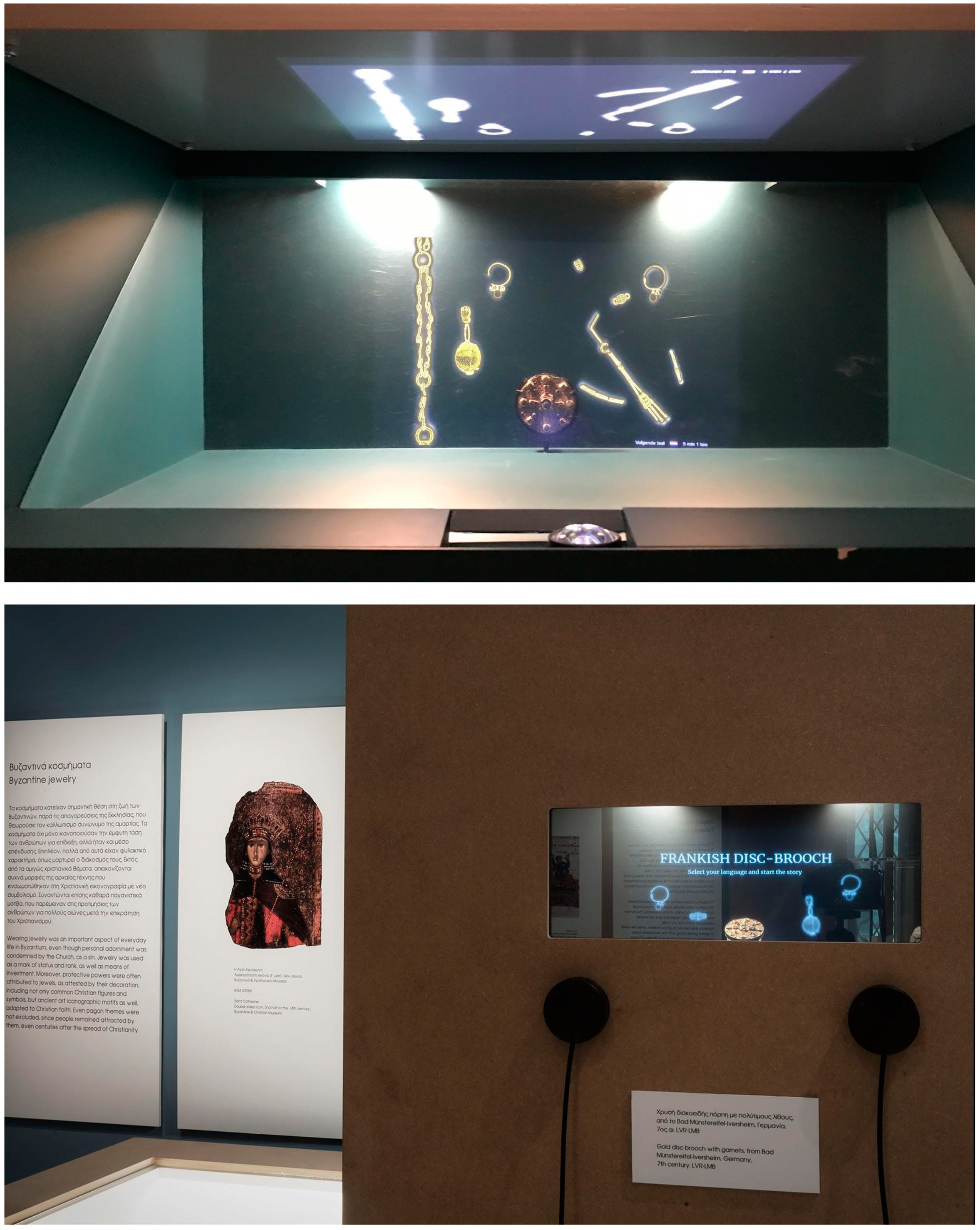

3. The CEMEC Case Study: The Box of Stories

3.1. Purposes, Topics, Steps of Work

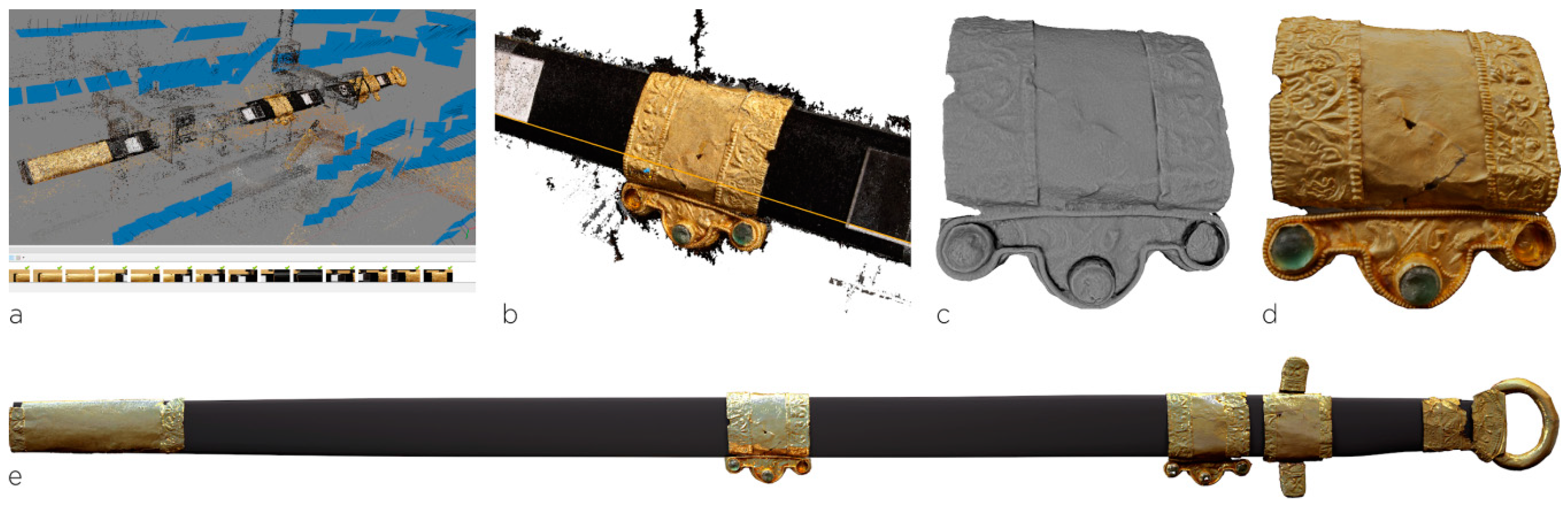

- Kunàgota sword. An Avar sword exposed at the National Hungarian Museum of Budapest (NHM), belonged to an Avar chief of the village of Kunàgota. It was never used because it represented a protective object for the afterlife of the buried man.

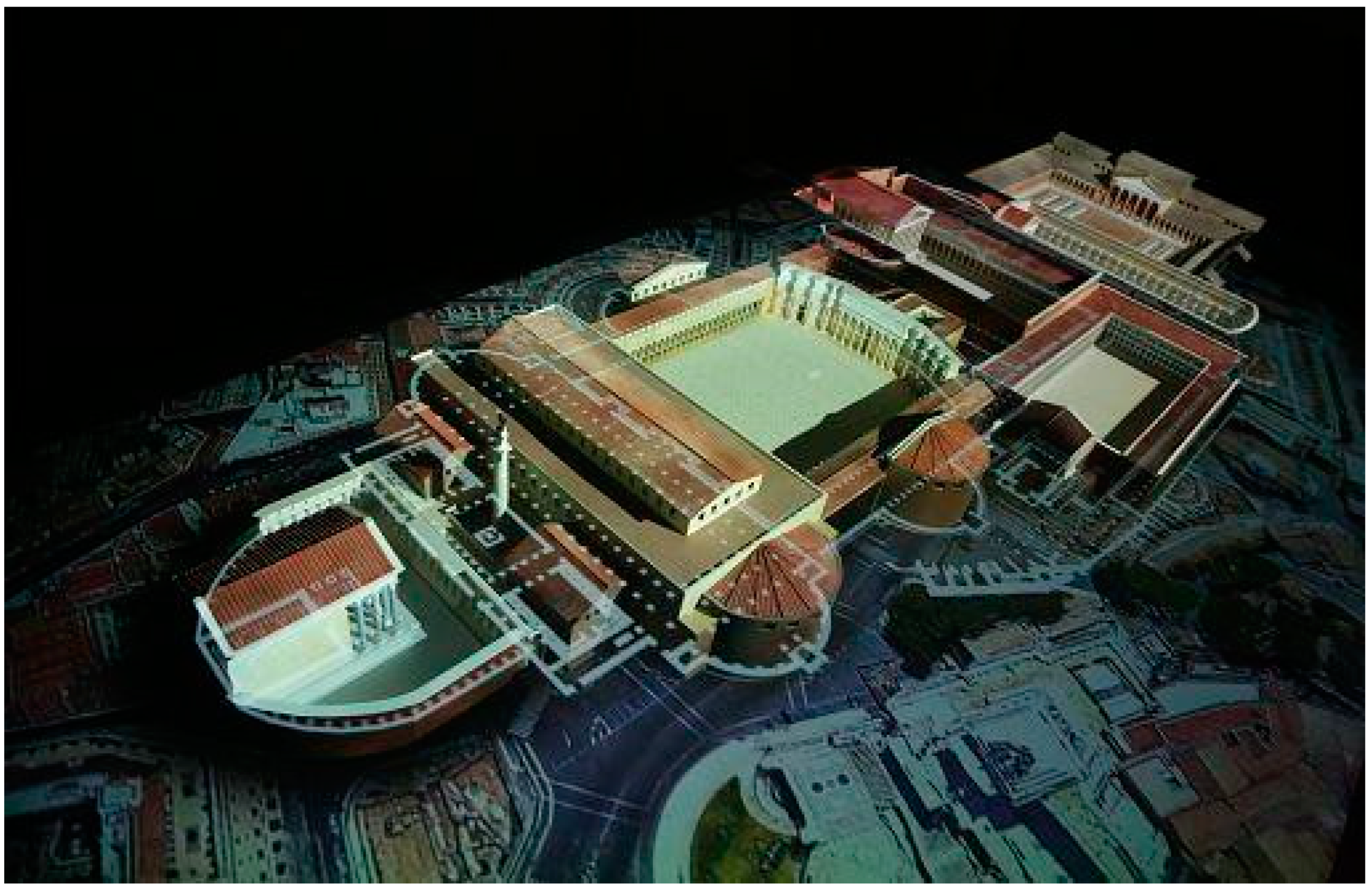

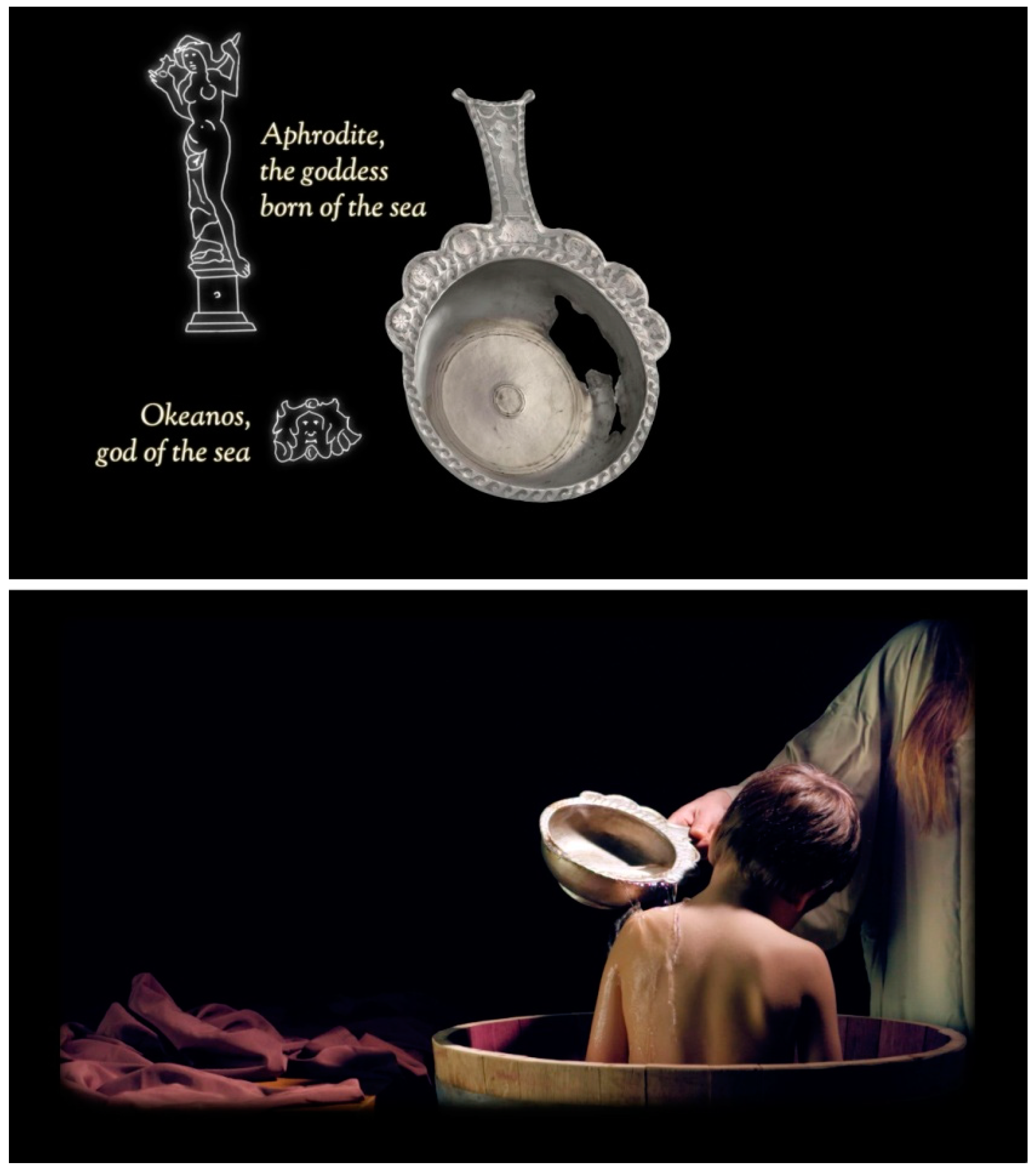

- Mytilene treasure. A set of Byzantine objects from the Byzantine and Christian Museum of Athens, specifically a golden bracelet, a candlestick and a trulla, a tool for water’s spilling, belonged to a wealthy family that lived on the Mytilene island, in front of Asia Minor coast. These objects were part of the domestic equipment.

- infrastructure design (the skeleton of the showcase; the choice of the hardware);

- production of 3D and multimedia contents to be harmonized with real objects;

- implementation of a real time rendering platform in VVVV software, able to synchronize audio-video play-out, lights, external devices: along a multi-track timeline all the audio-visual events are organized and managed according to a precise sequence;

- management of Arduino/MIDI controller, to manage real lights along a timeline and to control buttons for language selection;

- light design (seven led lights inside the showcase switch on and off on real objects);

- interaction and user experience design.

- stand-alone showcase (dimensions 1.50 × 1.40 × 2.50 m)

- showcase inserted in a projection wall 4 m wide and 2.50 m high.

3.2. The Kunàgota Sword Tells the Story of the Avars

- the holographic showcase integrated in a wider projection wall, presented in the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, in the context of the exhibition “Avars Revived” (February–May 2017) (Figure 11);

- the holographic showcase in its stand-alone version, without projection wall, presented in the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam, in the context of the “Crossroads” exhibition (September 2017–April 2018) (Figure 12).

3.3. The Mytilene Treasure Tells the Story of a Byzantine Family

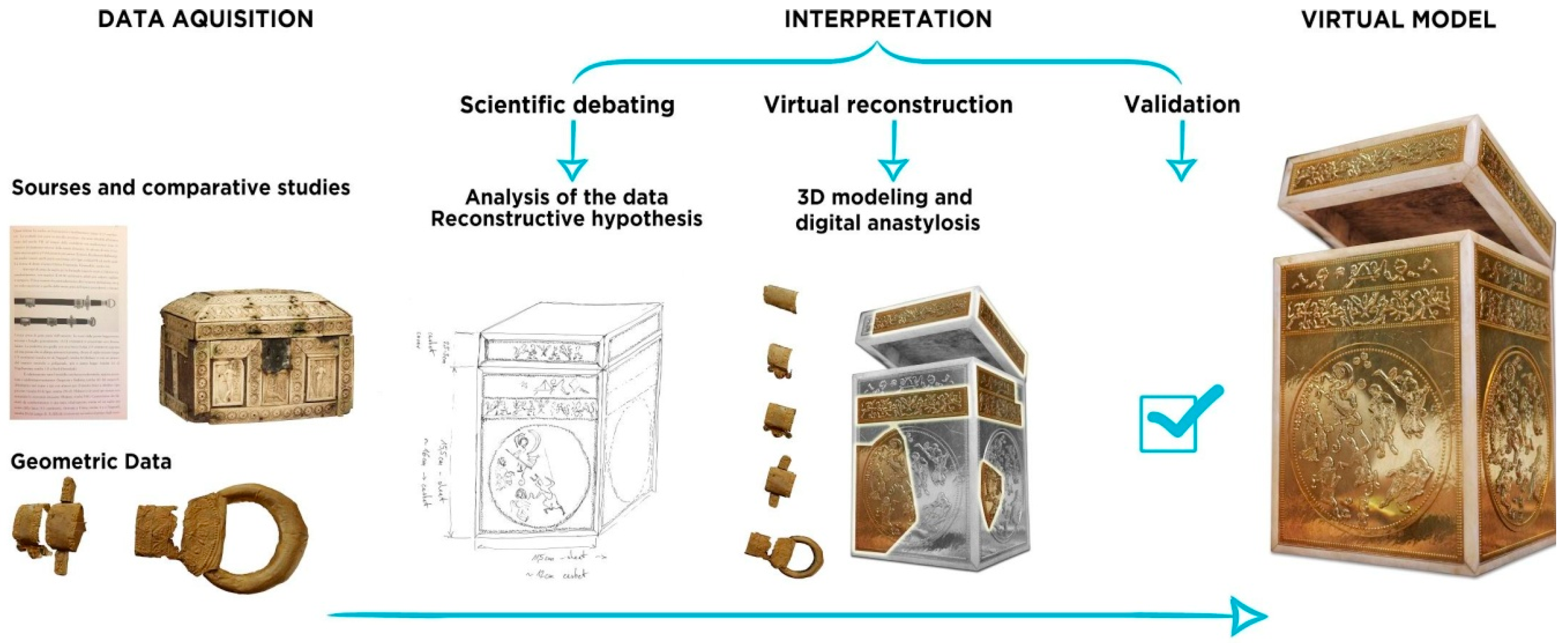

3.4. Virtual Reconstructions and Visual Mood of Kunàgota Sword and Mytilene Treasure

3.5. User eXperience (UX) Evaluation

3.5.1. Background Information

- Users are the museum visitors, given that the application has been only presented during temporary itinerant exhibitions (five months in each venue) of the CEMEC museum partners. For such a reason, motivation behind the visit can be merely referable to [42]:

- curiosity towards the subject of the exhibitions (i.e., Avars, Early Medieval Age, Byzantines and Christians);

- touristic needs if users were not citizens of the city where the CEMEC exhibitions were hosted—museums as landmarks that “MUST be seen” when in a foreign city;

- professional interest towards the subject and the technology used into the exhibitions, given the previous academic background of some users and their actual professional activity (i.e., researchers, academics, curators, project managers...);

- educative reasons which could push families and educators (i.e., teachers, students...) to deepen the topic proposed by the CEMEC exhibitions;

- commercial and promotional plan of project managers, politics, and cultural departments;

- social interaction between school groups, families, and people sharing the same interests.

- What generally capture users’ attention inside museums and bring them to love or not a digital product is [6,43]:

- the overall atmosphere—quiet, comfortable, familiar, and clear;

- the type of interaction—easy to practice, quick to access the related content, and shareable with friends and others;

- the graphic interface and the soundscape—colors, music, volume of music and visibility of commands highly influence the attractiveness of the digital application and its memorability in the future;

- the type of story and the way it is told—this datum is relevant to maintain the attention of users during the fruition of the digital application.

- The reliability of the 3D content in correspondence with the real artifact on show stays into [44]:

- the high quality of the 3D models in terms of shape, colors and visual effects (i.e., materials, reflection, light effects, shadows, aging effects, and so on) which could allow users to have a perception of real, of a ‘credible’ object;

- the overlapping of real museum object and its 3D model in order to produce a sense of continuity between virtual and real, reconstructed and virtually restored;

- the characterization of the storytelling which is composed by (a) the type of the cultural notions cited along the story; (b) the level of ‘insights’ intended as curiosities and factual information granted to the users; and (c) the voice who tell the story (Is it a real character or the object itself?).

3.5.2. UX Evaluations—Multi-Partitioned Analysis

- A general analysis, at a time prior to the main UX survey, on the general museum environment. This was important in order to study the context of fruition and the exhibition availabilities, how the visitors usually approached the space and the objects exposed, which were the interesting points of the museum visit path and which were less interesting, which was the visitors’ favorite pathway, the affluence of public in museum spaces, and how the institution included any digital and multimedia equipment throughout the exhibition. Statistics, maps, reports, and so on were really useful to study the CEMEC hosting museums.

- The UX survey on public, during the museum visit at the holographic showcase, by means of observations, to verify and analyze the practicability of this expositive solution included into the visit tour, the related effectiveness compared to traditional cultural panels and its relationship with the permanent collection on display.

- After the museum experience, by means of paper-based questionnaires, to verify the users’ feedback in respect to certain notions acquired or not when interacting with the installation, the usability and the interface design.

- Observations. They allowed us to have an overview of the users’ behavior toward the holographic showcase in terms of visibility of the digital product along the museum path, user’s attitude toward it, time of permanence in front of it, type of visit (single or group), attention or distraction while watching the story inside the showcase, need for help to make the story starts. It was mainly composed by three sections: (a) demographic data to be collected in general form (gender, age); (b) users’ behavior to be transcribed in form of written texts and into a grid of values (like actions, face miming, gestures, and comments); (c) context of fruition to be analyzed in relation with the overall environment and the museum room hosting the holographic showcase, and the user social behavior (alone or in group). Open comments for operators were also available at the end of the observation template, allowing extra notes to be included as relevant for the report. Each observed user had a corresponding document, progressively numerated and reporting information about date and period of the observation.

- Direct questionnaires. They gave the chance to gather direct feedback of users to confront to what just observed by operators, finding a common sense and interpreting users’ reactions putting comments into contexts of reference. The template was again composed by three parts: (a) questions about the system’s usability and the visibility of the graphic elements and of the real objects; (b) questions about the storytelling, the clearness of the content proposed and the language understandability; (c) closing questions about the appreciation and the enjoyment of the experience just had with the holographic showcase. All these questions matched and intersected and then related to the observation protocol, revealed a the users’ behavior and activities, their level of reliability, and commitment towards the evaluation (Figure 18).

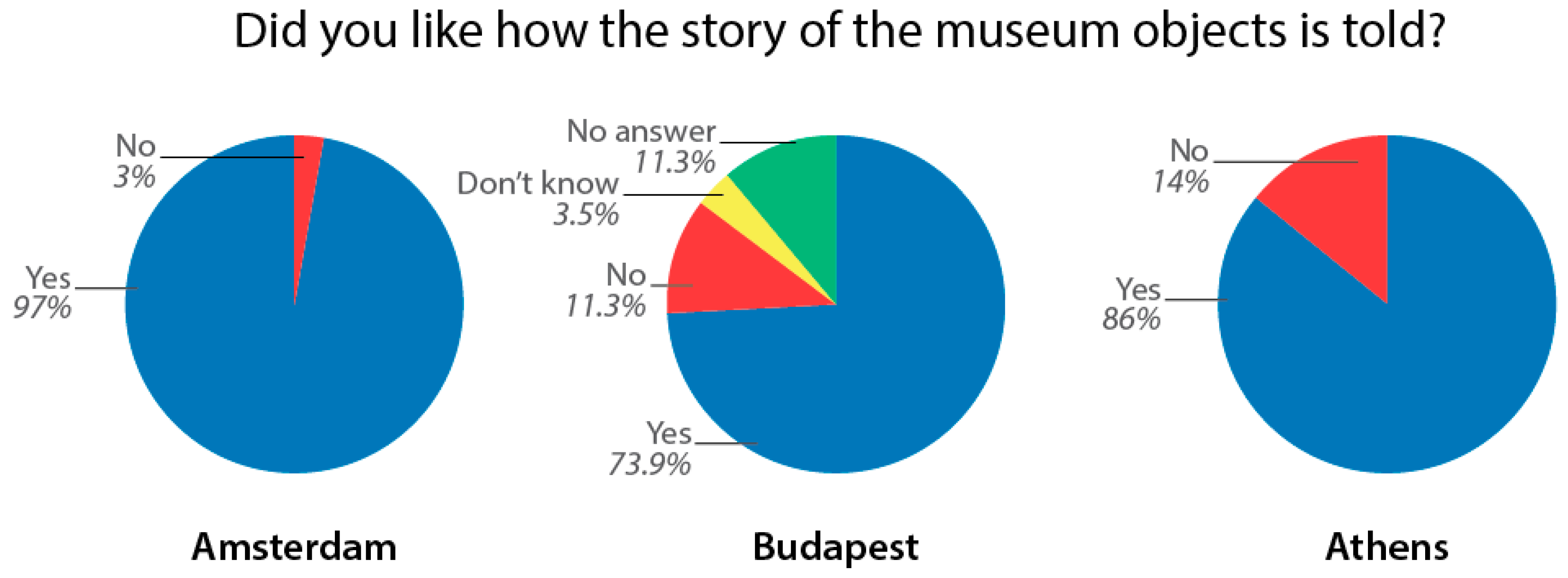

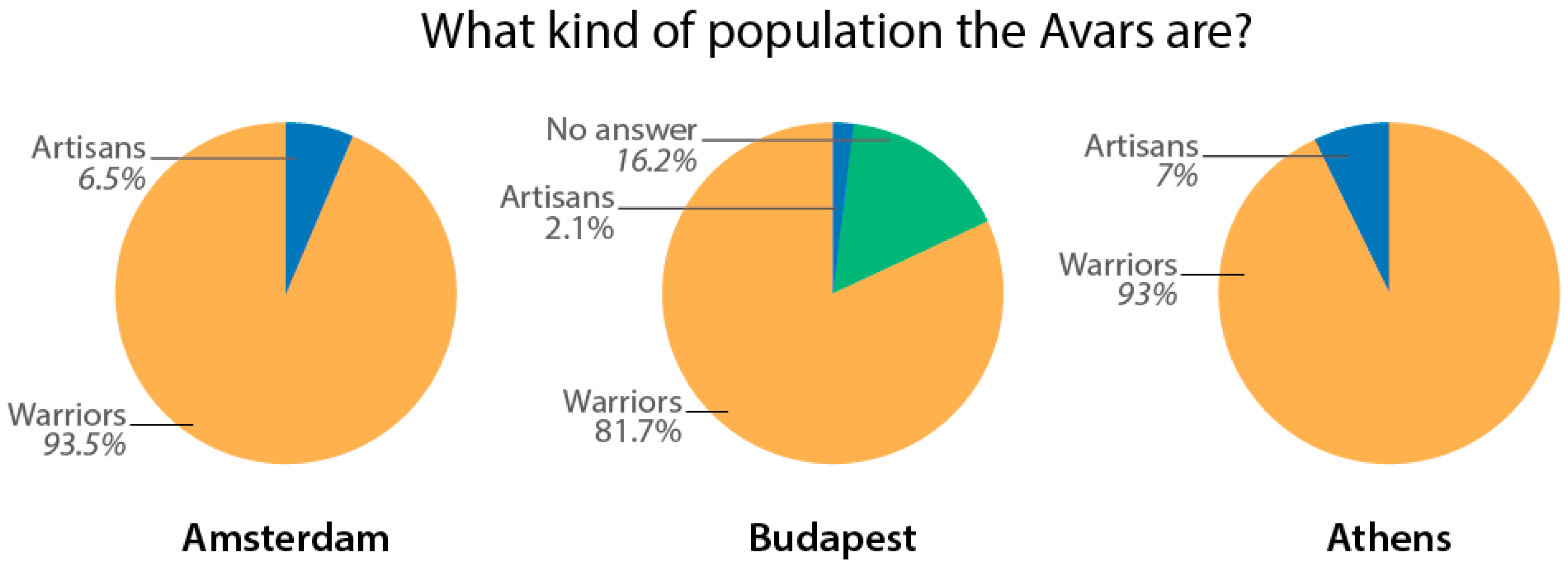

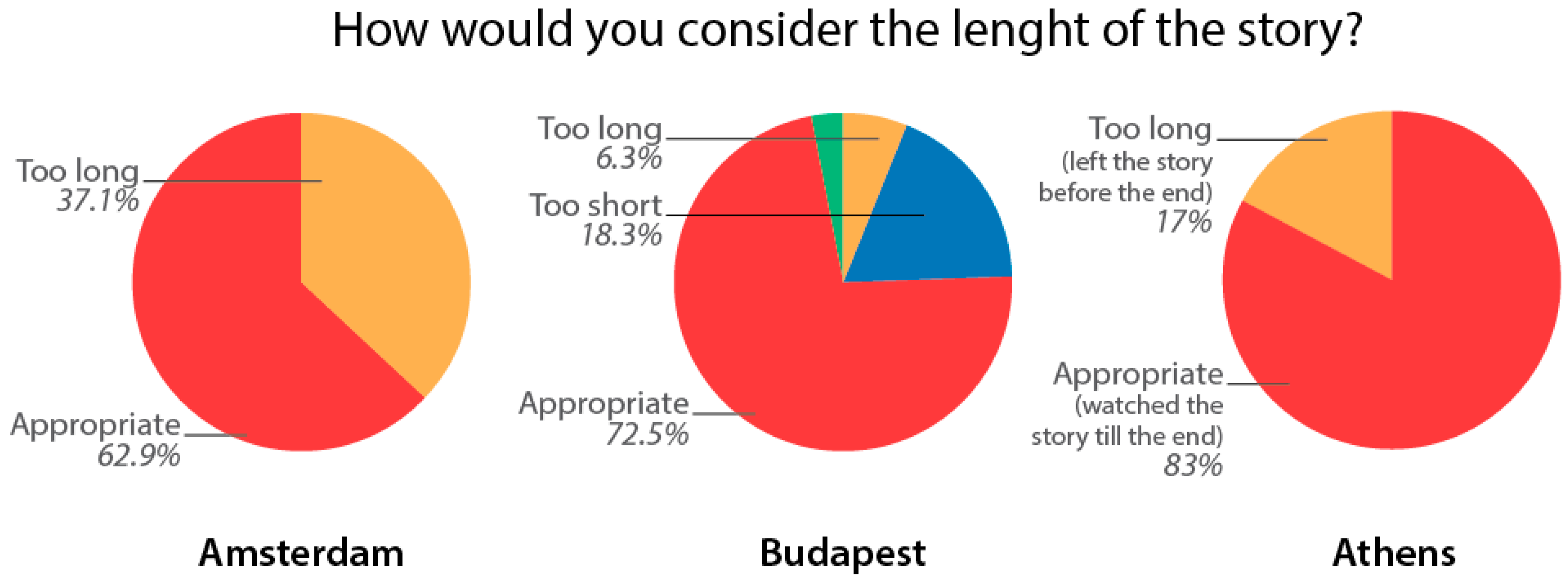

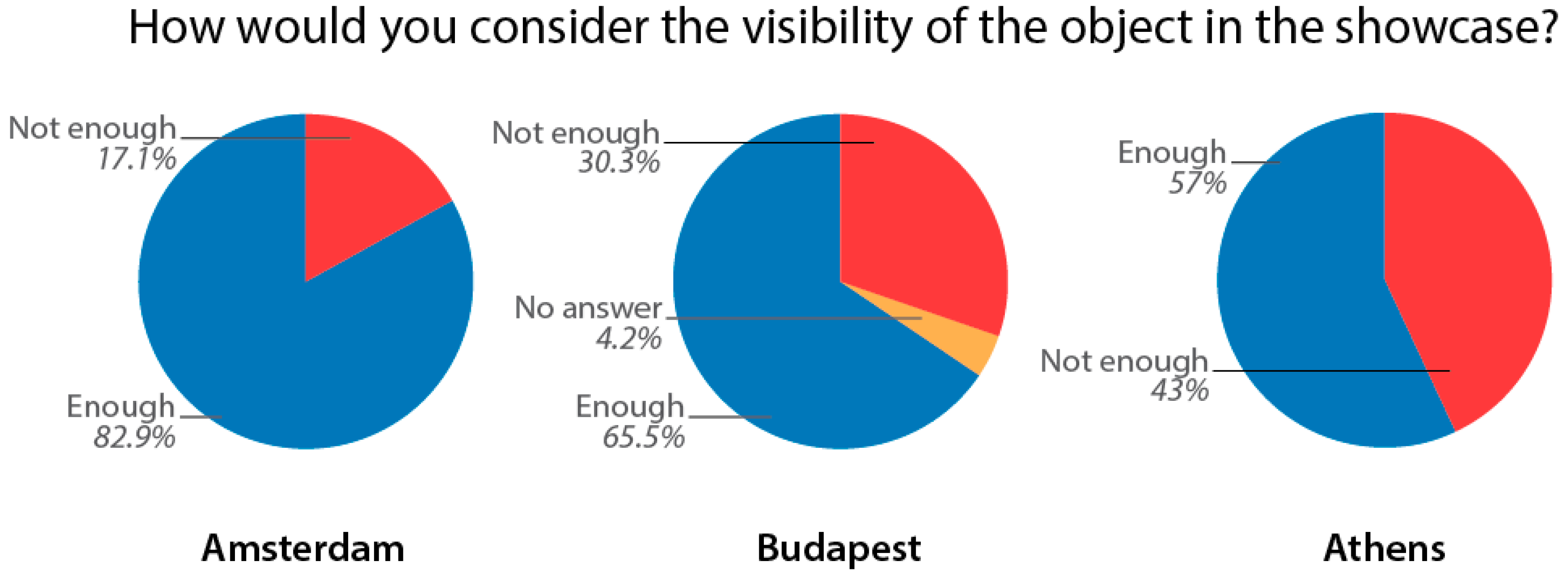

3.5.3. Results

3.5.4. ‘Taste’ of the Overall Experience

3.5.5. Storytelling

3.5.6. Users’ Attitude

3.5.7. Context of Fruition

3.5.8. System and Interface Design

4. Guidelines

4.1. Overall Experience: The Showcase in the Museum Space

- users’ previous expectations when visiting a cultural place (i.e., learn something new; see something studied; spend time with friends and families…);

- their (mental and emotional) predisposition at multimedia inside museums;

- availability to interact with digital system;

- time at disposal to dedicate to such installation;

- interest and curiosity toward such way of exploring the museum’s content.

- The dynamicity of the user visit path. In the majority of the cases, the museum visitors have to follow a precise museum visit path which includes also the digital installations; they have to retrace the curatorial line which blend together all the museum objects in a thematic or chronological manner. When in front of the typical showcase, visitors have always the same behavior: reading, observing, confronting, or listening to the audio-guide; differently, when in front a ‘digital’ showcase, the situation changes and they need to adapt their behavior to what is proposed: interact, watch, follow a precise story, listen to voices and music. If the museum thematic path is coherent, users will not have difficulties in following it.

- The discomfort of the user in front of the system. The holographic showcase ‘obliges’ visitors to stop in front of it in order to listen to the story and watch the image floating around the museum object. This aspect may influence the experience given that a person stands still and at a certain distance from the digital showcase to benefits of the content. The users can be tired so they can decide to leave after a while; or, if they seat, may obstacle the passage of other visitors and the latter can walk across them and hide the visual of who is sitting. Therefore, studying the best solution in terms of comfort and user experience is a positive point.

- The ‘wow’ effect of the holography. The hologram has something magic in its apparition given its game of reflections. Wonder and surprise surely lead visitors towards such digital installation. Attractiveness is thus crucial when planning a type of experience like the holographic one: colors, voices, superimposition, and a good storytelling are the key elements; it is important to work on visitors’ emotions and sensations in order to get the best way of telling what is behind the museum object: ancient visions, evocations, dreams, and beliefs.

4.2. Environmental Conditions, Setup Precaution, Public Management

- the cultural message to be transmitted to the audience;

- the exposition to be correctly addressed to the selected target groups;

- the language, atmosphere, and flavor of the exhibition to be coherent and coordinated;

- the security and the condition of display of objects to be respected;

- the safety of the museum environments for people to be respected.

- Are they following a guided visit or are they free to go wherever they prefer?

- Are they using a multimedia tool to support their visit in the museum/exhibition or are they only using the exposition panels only?

- How can the all the different communicative supports work coherently?

4.3. Perceptual Aspects

- First of all, the space along the z axis must be recognizable by the user. For this reason, if the holographic showcase has a solid background, it needs to be as deep as possible, so that the projection plane is not too adherent to the background itself.

- Moreover, the solid background must be somehow visible, a bit illuminated, because the depth (that is the distance between the hologram’s projection plane and the background) must be perceivable, otherwise the effect will look like a movie on a normal screen.

- Visual interferences are a positive factor for a rich perception of a hologram. For this reason, if we leave the background transparent, it is much better to locate a holographic showcase in the middle of a space, rather than close to a wall (on the back). In such a condition, the floating effect of the images will become much more evident (Figure 23). Obviously, in the case of a transparent background, random interferences will occur, and this is not a problem at all. Nevertheless, a very interesting research field is actually the creation of increasingly effective setups, in order to obtain specifically designed interferences in the holographic spectacle. That is to say that a conscious use of visual interferences between real world and holograms is contemplated.

4.4. Setup of the Showcase

- A good lighting system upon the museum objects inside the showcase;

- Avoiding as much as possible reflections on the frontal glass closing the window;

- A transparent background. Instead of closing the back of the structure with an opaque panel, a glass or a plexiglass panel can be used, so that visitors can walk to the back and look at the objects from a very short distance, admiring every detail. From the back side, the ghost is not perceivable, because it can be perceived only looking from the front side. Therefore, the holographic showcase can work as a traditional showcase if accessed from the back, and as an ‘augmented’ one if accessed from the front. Of course, in the general environment of the room, the light must not be too intense (a semi-dark condition is ideal), otherwise the light could invade the showcase and the ghost could become not well perceivable in its details and brightness.

4.5. Interaction

- Be not an expedient itself, only because it is associated with the concept of technological innovation. Interaction can be an element of technological innovation, but it is not the only one, if misused it becomes a barrier for the public. Technological innovation also lies in the visualization and dramatization of a scenic space through digital technologies;

- Really create added value for the public, that is, be a structural part of the idea of fruition and experience and not an occasional or pretentious element;

- Be supported by the museum staff, who are able to observe the visitors and help them in case they do not understand how to act. Sometimes, this is a problematic aspect in museums because there is not always a dedicated staff inside of them.

4.6. Storytelling, Cultural Transmission, and Dramaturgy of the Object

- Where was the object found? Was it the original place in which it was used?

- Which period is the object referred to?

- Which was the context of use of the object?

- Do we know something about the identity of the owners? What about their social status and job?

- How was the life in the place where the object was used at that time? Who lived there? Which job or activities did those people carry on?

- Where was the object preserved/used during its daily life? In a house, in a palace, in a religious environment, in a shop, in a tomb….

- Was the object used in the daily life or was it exhibited by the owners just for its symbolic value?

- Did the object belong to a woman or a man?

- Which historical events can be connected to the object’s life? Is it possible to mention any episode in particular?

- Was the object belonging to a standard typology or was it unique and special? Was it a cultural transmitter for successive generations/cultural patterns?

- Which materials was it made of? What about the manufacturing process?

- Which is the provenience of the object’s materials?

- Which main characters can be associated to the story of the object? Warriors, merchants, politics, artists, goldsmiths, emperors…?

- Is the object connected by a common significance to the others exhibited beside (in the same showcase or in the showcases nearby)? If yes which are the most notable relations?

- What about digital restoration of this object? Which are the limits according to you?

- Do you agree with virtual reconstruction of shape and decoration? Do you agree with simulation of the original aspect of the materials?

- Do you think that the same criteria of real restoration should be respected also in the case of virtual restoration, (distinction between original and restored/ different layers of visualization)?

4.7. Audio-Visual Grammar to Creating the Illusion

4.7.1. Coexistence of Real and Virtual

4.7.2. 3D Graphics

4.7.3. Background of the Ghost

4.7.4. The Whole Image in the Frame

4.7.5. Scale Factor

4.7.6. Position of the Real Object on the Stage

4.7.7. Still Camera

4.7.8. Camera Point of View and FOV

4.7.9. Camera Depth of Field

4.7.10. Light and Color Matching

4.7.11. Shadow Coherence

4.7.12. Charm

4.7.13. Sounds

4.7.14. Sound Spatialization

4.8. Overlapping of Real and Virtual

4.9. Virtual Replica and Virtual Reconstructions

- At the beginning, some precautions are kept during the acquisition, like (a) the positioning of the museum artifacts to be digitized; (b) the number and point of view of the shoots; and (c) lighting setup [49].

- When the acquisition has finished, the entire dataset of images is imported within Agisoft Photoscan, SFM software, to find correspondences between images and perform the photogrammetric model. During the image alignment, the software automatically finds tie points and camera parameters. Subsequently, dense cloud is computed.

- After the optimization of the dense cloud, the mesh is calculated using the Poisson surface reconstruction algorithm which allows to reconstruct a triangle mesh from the point cloud. The last step is the parameterization of the model and the generation of textures. As texture generation parameters, a combination that uses the weighted average value of all pixels from all images of the dataset to blend them in a single atlas texture was used to map the model (Figure 27).

4.10. Monitoring and Recording Users’ Behavior

4.11. Sustainability

- ○

- Maintenance—The holographic structure is characterized by a reusable and long-lasting setup. The hardware is made with aluminum sections bars and panel that can be adapted to every location and can be easily replaced; it is easy to realize and stable in the everyday management.The software to manage the entire application, is completely customizable to control different type of media: video, sound, lights, touch and physical interfaces, sensors for environmental monitoring. The computing and networking infrastructure is robust and can be continuously monitored and updated via web using a remote controlling software.

- ○

- Compatibility—Among the holographic techniques, the Pepper’s Ghost effect is not only able to produce a high-quality 3D perception, it is also fully compatible with the conservation needs and the museographic constraints, as it does not damage the museum’s artifact in the showcase. Furthermore, the objects are completely inaccessible and protected within a secure holographic showcase.

- ○

- Exchangeability—The structure can be easily mounted and dismounted in a couple of days and can easily travel together with museum objects for temporary exhibitions, as experimented in the CEMEC project (https://cemec-eu.net) where the Kunàgota sword was shown in different locations (Budapest, Amsterdam, and Bonn). Another advantage of this kind of installation is that it can work also with physical replica of the museum artifacts. The recent evolution of 3D printing technologies allows 3D scanned models of objects, originally digitized to produced virtual animation, and then to be also used for printing physical copies.

- ○

- Scalability—The creative workflow and the overall setup is completely adaptable and scalable since it can be adjusted to different museum contents. The holographic structure (dimension, setup, multimedia duration, type of visualization, integrations of projection wall,….) can be thus tailored on diverse situations we can encounter inside museums.

5. Conclusions

- the context of use

- the environmental conditions (silent or noisy, dark or illuminated, secluded or crowded)

- the target age

- the conditions of content accessibility

- the time of usage

- the possibility of intervention on the physical space hosting the installation

- the expectations of curators and visitors.

- No stories are told about each single museum object about the owners, the place of belonging and manufacturing and the period of its persistence. Only a cold list of facts and factual information are often presented in captions or panels inside museums. The practice of storytelling is yet not fully exploited inside cultural venues.

- No relations are revealed and brought to light between objects of the same collection; museums address their exposition ordering the pieces by age or provenance and not by theme or subject.

- No contextual description about museum objects is presented. Specifically, reconstructions about the function, the usage, the environment in which it was included, the atmosphere of that specific period in history and so on. A long tradition of physical paper-based setting reconstructions can be today retractable in museums [56]; however, with the development of technology and the advancement in multimedia techniques, the same reconstructions can be easily translated in 3D and made interactive, allowing more involvement and immersiveness for the final users.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pescarin, S. Museums and virtual museums in Europe: Reaching expectations. SCIRES-IT 2014, 8, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Antinucci, F. Musei Virtuali; Laterza: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garzotto, F.; Rizzo, F. Interaction paradigms in technology-enhanced social spaces: A case study in museums. In Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, Helsinki, Finland, 22–25 August 2007; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.C. From Knowledge to Narrative: Educators and the Changing Museum; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Antinucci, F. Parola e Immagine, Storia di due Tecnologie; Laterza: Roma, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E.; Pagano, A.; Poli, C. The Tiber Valley Museum: User Experience Evaluation in The National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference in Central Europe on Computer Graphics, Visualization and Computer Vision, WSCG 2016, Pilsen, Czech Republic, 30 May–3 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, A.; Pietroni, E.; Cerato, I. User experience evaluation of immersive virtual contexts: The case of the Virtual Museum of the Tiber Valley project. In International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, Spain, 3–5 July 2017; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-697-3777-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, L. Storytelling: The real work of museums. Curator Mus. J. 2010, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danks, M.; Goodchild, M.; David, K.; Arnold, B.; Griffiths, R. Interactive storytelling and gaming environments for museums: The interactive storytelling exhibition project. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; Volume 4469, pp. 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E.; Pagano, A.; Fanini, B. UX Designer and Software Developer at the Mirror: Assessing Sensory Immersion and Emotional Involvement in Virtual Museums. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2018, 2, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, F.; Riva, G. Conoscenza, Comunicazione e Tecnologia. Aspetti Cognitivi della Realtà Virtuale; LED Edizioni Universitari: Milano, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, A.; Pietroni, E.; Poli, C. An integrated methodological approach to evaluate virtual museums in real museum contexts. In Proceedings of the ICERI 2016, Seville, Spain, 14–16 November 2016; pp. 310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gockel, B.; Eriksson, J.; Graf, H.; Pagano, A.; Pescarin, S. VMUXE, An Approach to User Experience Evaluation for Virtual Museums. In Proceedings of the HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 21–26 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E. Virtual museums for landscape valorization and communication. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, F.; Kenderdine, S. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muratori, M. Olografia—Principi ed Esempi di Applicazioni. Available online: http://www.crit.rai.it/eletel/2006-3/63-indice.html (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Muratori, M. Olografia: Quale Realtà. Available online: http://www.crit.rai.it/eletel/2015-1/151-3.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Alberico, F. Cos’è l’olografia. Elettronica e Telecomunicazioni 1976, 5. Anno XXV. [Google Scholar]

- Bove, V.M. Live Holographic TV: From Misconceptions to Engineering. In Proceedings of the SMPTE International Conference on Stereoscopic 3D for Media and Entertainment, New York, NY, USA, 21–22 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.C.; Rampal, V.V. Lasers and Holography; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993; pp. 258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cutnell, J. L’interferenza e la natura ondulatoria della luce. In Elementi di Fisica; Zanichelli: Bologna, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Herz, R.; Merfeld, D.; Wolfe, J.; Bartoshuk, L.; Lederman, S.; Levi, D.; Klatzy, R.; Kluender, K. Sensation and Perception; Zanichelli: Bologna, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Raabe, G.A.; Schlessinger, R.J. System for Generating a Hologram. U.S. Patent No. 3,647,959, 7 March 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, H.; Zarei, T.; Farahani, N.; Granmayeh Rad, A. Studying the Recent Improvements in Holograms for Three-Dimensional Display. Int. J. Opt. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P. The Visual Language of Holograms. In Advanced Holography—Metrology and Imaging; Naydenova, I., Ed.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-953-307-729-1. [Google Scholar]

- Porta, J.B. Natural Magick. In Sioux Falls; NuVision Publications: Canton, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 9781595472380. [Google Scholar]

- Phantasmechanics Presents Help with Pepper on It. Available online: http://www.phantasmechanics.com/pepper.html (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Steinmeyer, J.H. The Science Behind the Ghost; Hahne: Burbank, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, J.H. True History of the Ghost and All about Metempsychosis; Cambridge Library Collection: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781108044349. [Google Scholar]

- Mickael Jackson Hologram at Billboard. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fVUvWOESZLY (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Allard Pierson Museum. Crossroads. Traveling through Europe, 300–1000 AD; Allard Pierson Museum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 97 89 46258 2231. [Google Scholar]

- CEMEC. Available online: https://cemec-eu.net (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Pietroni, E.; d’Annibale, E.; Ferdani, E.; Forlani, M.; Pagano, A.; Rescic, L.; Rufa, C. Beyond the museum’s object. Envisioning stories. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, EDULEARN17, Barcelona, Spain, 3–5 July 2017; pp. 10118–10127. [Google Scholar]

- Guidazzoli, A.; Liguori, M.C.; Luca, D.D.; Imboden, S. Valorizzazione cross-mediale di collezioni museali archeologiche Italiane. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2014, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassatelli, G.; Russo, A. Il Viaggio Oltre la Vita, gli Etruschi e l’aldilà tra Capolavori e Realtà Virtuale; Bononia University Press: Bologna, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-7395-981-6. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: www.futouring.com (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Welcome to Rome. Available online: welcometo-rome.it/ (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Pescarin, S. Keys to Rome. Roman Culture, Virtual Museums; CNR ITABC: Rome, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-902028-2-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, A.; Ferdani, F.; Pietroni, E.; Szenthe, G.; Bartus-Szöllősi, S.; Sciarrillo, A.; d’Annibale, E. The box of stories: User experience evaluation of an innovative holographic showcase to communicate the museum objects. In Proceedings of the International Forum, State of Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 15–17 November 2018; The State Hermitage Publishers: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2018; pp. 163–178. ISBN 978-5-93572-792-5. [Google Scholar]

- Debevec, P. Rendering synthetic objects into real scenes: Bridging traditional and image-based graphics with global illumination and high dynamic range photography. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Orlando, FL, USA, 19–24 July 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ergonomics of Human-system Interaction—Part 210: Human-centred Design for Interactive Systems, ISO 9241-210:2010. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/52075.html (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Allan, M.; Altal, Y. Museums and tourism: Visitors motivations and emotional involvement. Med. Archaeol. Archaeometry 2016, 16, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E.; Pagano, A.; Amadei, M.; Galiffa, F. Livia’s Villa reloaded Virtual Museum: User experience evaluation. In Proceedings of the 9th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI), Seville, Spain, 14–16 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Unto, N.; Leander, A.M.; Dellepiane, M.; Callieri, M.; Ferdani, D.; Lindgren, S. Digital reconstruction and visualization in archaeology: Case-study drawn from the work of the Swedish Pompeii Project. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress, Marseille, France, 28 October—1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Tcha-Tokey, K.; Christmann, O.; Loup-Escande, E.; Loup, G.; Richir, S. Towards a Model of User Experience in Immersive Virtual Environments. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, N.; Chandler, J.H.; Stuart, N.L. Structure from Motion (SFM) Photogrammetry; British Society for Geomorphology: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Remondino, F.; Spera, M.G.; Nocerino, E.; Menna, F.; Sex, F. State of the art in high density image matching. Photogramm. Rec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Nicolae, E.; Nocerino, E.; Menna, F.; Remondino, F. Photogrammetry Applied to Problematic Artifacts. The International Archives of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 40.5 (2014): 451. Available online: http://www.isprs.org/publications/archives.aspx (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Tucci, G.; Cini, D.; Nobile, A. Effective 3D digitization of archaeological artifacts for interactive virtual museum. In Proceedings of the 4th ISPRS International Workshop 3D-ARCH, Trento, Italy, 2–4 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- López-Menchero Bendicho, V.M.; Gutiérrez, M.F.; Vincent, M.L.; Grande León, A. Digital Heritage and Virtual Archaeology: An Approach Through the Framework of International Recommendations. In Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- London charter for Computer-Based Visualization of Cultural Heritage. Available online: http://www.londoncharter.org/principles.html (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Barcelò, J.A.; Forte, M.; Sanders, D.H. Virtual Reality in Archaeology. In BAR International Series; British Archaeological Reports: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- International Principles of Virtual Archaeology. The Seville Principles. Available online: http://sevilleprinciples.com/ (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Pietroni, E.; Pagano, A. Un metodo integrato per valutare i Musei Virtuali e l’esperienza dei visitatori. Il caso del Museo Virtuale della Valle del Tevere. In Atti del Workshop 15 Dicembre 2016 Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia; CNR: Roma, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788890202834. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdani, D.; Pagano, A.; Farouk, M. Terminology, Definitions and Types for Virtual Museums. V-Must.net del. collections. 2014. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/6090456/Terminology_definitions_and_types_of_Virtual_Museums (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Lorraine, E.M.; Gary, W.E. Museums as Learning Settings. The Importance of the Physical Environment. J. Mus. Educ. 2002, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pietroni, E.; Ferdani, D.; Forlani, M.; Pagano, A.; Rufa, C. Bringing the Illusion of Reality Inside Museums—A Methodological Proposal for an Advanced Museology Using Holographic Showcases. Informatics 2019, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6010002

Pietroni E, Ferdani D, Forlani M, Pagano A, Rufa C. Bringing the Illusion of Reality Inside Museums—A Methodological Proposal for an Advanced Museology Using Holographic Showcases. Informatics. 2019; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePietroni, Eva, Daniele Ferdani, Massimiliano Forlani, Alfonsina Pagano, and Claudio Rufa. 2019. "Bringing the Illusion of Reality Inside Museums—A Methodological Proposal for an Advanced Museology Using Holographic Showcases" Informatics 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6010002

APA StylePietroni, E., Ferdani, D., Forlani, M., Pagano, A., & Rufa, C. (2019). Bringing the Illusion of Reality Inside Museums—A Methodological Proposal for an Advanced Museology Using Holographic Showcases. Informatics, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6010002