Leveraging Informatics to Manage Lifelong Monitoring in Childhood Cancer Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

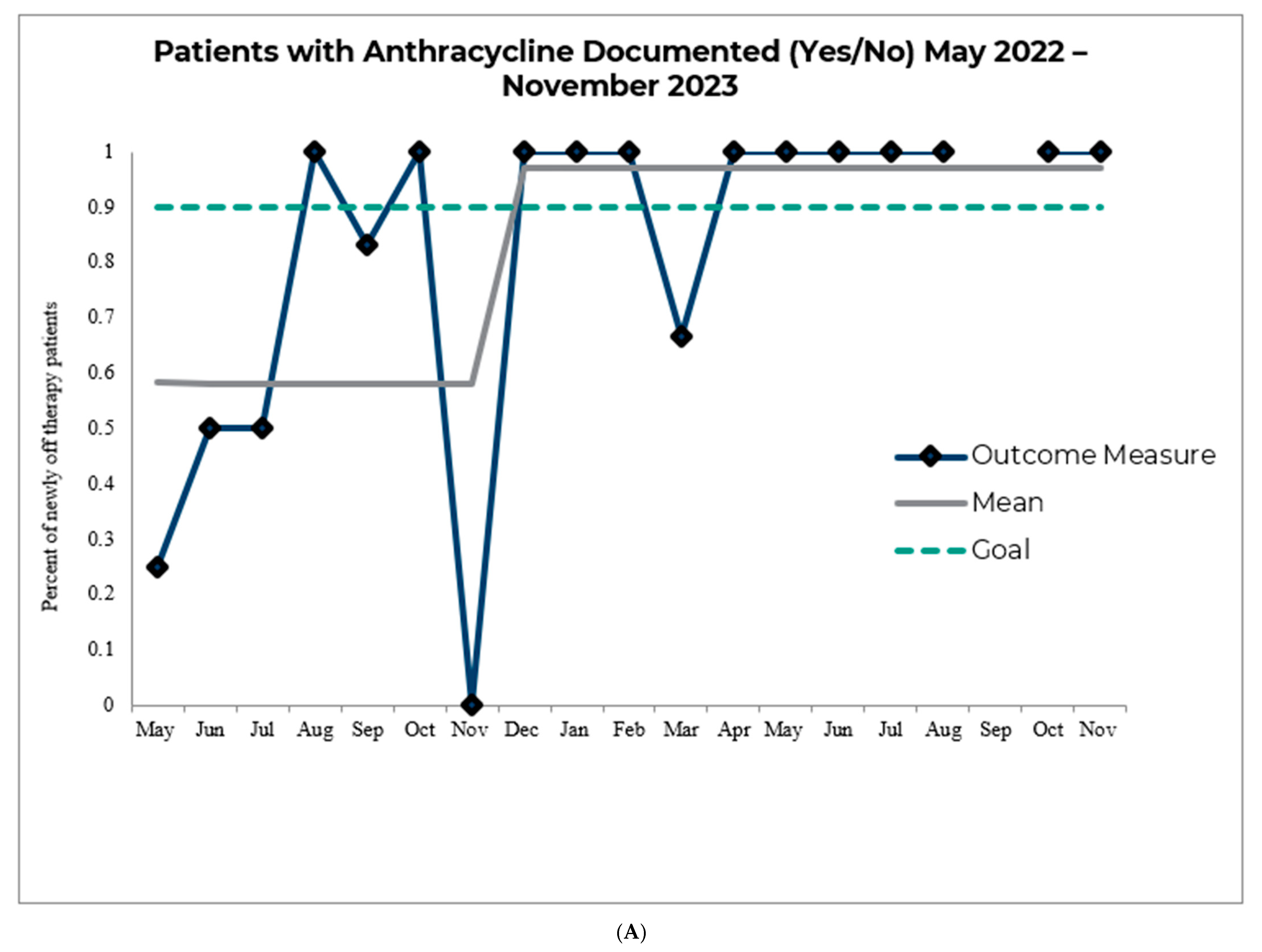

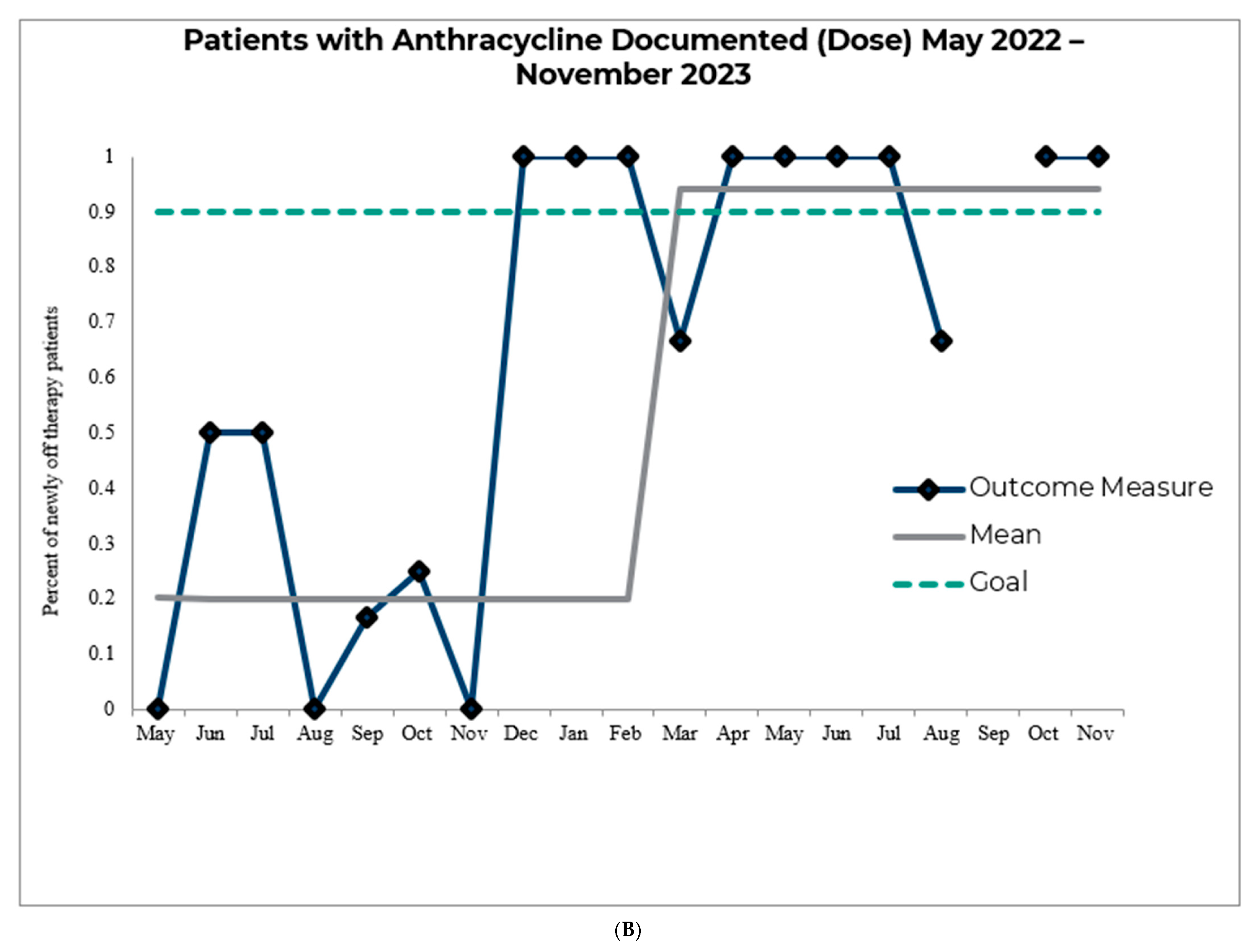

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millard, W.B. Electronic health records: Promises and realities: A 3-part series part I: The digital sea change, ready or not. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2010, 56, A17–A20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neidich, A.B. The promise of health information technology. Virtual Mentor. 2011, 13, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tondora, J.; Stanhope, V.; Grieder, D.; Wartenberg, D. The Promise and Pitfalls of Electronic Health Records and Person-Centered Care Planning. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 48, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burde, H. The HITECH Act: An Overview. Available online: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/hitech-act-overview/2011-03 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Tsai, C.H.; Eghdam, A.; Davoody, N.; Wright, G.; Flowerday, S.; Koch, S. Effects of Electronic Health Record Implementation and Barriers to Adoption and Use: A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis of the Content. Life 2020, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long-Term and Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/childhood-cancer/late-effects-of-childhood-cancer-treatment.html (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Holt, D.E.; Hiniker, S.M.; Kalapurakal, J.A.; Breneman, J.C.; Shiao, J.C.; Boik, N.; Cooper, B.T.; Dorn, P.L.; Hall, M.D.; Logie, N.; et al. Improving the Pediatric Patient Experience During Radiation Therapy-A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranade-Kharkar, P.; Narus, S.P.; Anderson, G.L.; Conway, T.; Del Fiol, G. Data standards for interoperability of care team information to support care coordination of complex pediatric patients. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltz, A.; Wu, C.L.; White, M.L.; Wilson, K.M.; Lorch, S.A.; Thurm, C.; Hall, M.; Berry, J.G. Characteristics of Rural Children Admitted to Pediatric Hospitals. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyd, D.H.; Berkman, A.; Howell, C.; Power, S.; Kreissman, S.G.; Landstrom, A.P.; Khouri, M.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Kibbe, W.A. Leveraging Clinical Informatics Tools to Extract Cumulative Anthracycline Exposure, Measure Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Assess Guideline Adherence for Children With Cancer. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2021, 5, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.; Coyne, E.; Crowgey, E.L.; Eckrich, D.; Myers, J.C.; Villanueva, R.; Wadman, J.; Jacobs-Allen, S.; Gresh, R.; Volchenboum, S.L.; et al. Implementation of a learning healthcare system for sickle cell disease. JAMIA Open 2020, 3, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathioudakis, N.; Jeun, R.; Godwin, G.; Perschke, A.; Yalamanchi, S.; Everett, E.; Greene, P.; Knight, A.; Yuan, C.; Golden, S.H. Development and Implementation of a Subcutaneous Insulin Clinical Decision Support Tool for Hospitalized Patients. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019, 13, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenian, S.H.; Armstrong, G.T.; Aune, G.; Chow, E.J.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Ky, B.; Moslehi, J.; Mulrooney, D.A.; Nathan, P.C.; Ryan, T.D.; et al. Cardiovascular disease in survivors of childhood cancer: Insights into epidemiology, pathophysiology, and prevention. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2135–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers, Version 6.0; Children’s Oncology Group: Monrovia, CA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.survivorshipguidelines.org (accessed on 1 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Davidow, K.A.; Gresh, R.; Kolb, E.A.; Guarnieri, E.; Cooper, M.R. Leveraging Informatics to Manage Lifelong Monitoring in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Informatics 2026, 13, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13020023

Davidow KA, Gresh R, Kolb EA, Guarnieri E, Cooper MR. Leveraging Informatics to Manage Lifelong Monitoring in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Informatics. 2026; 13(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavidow, Kimberly Ann, Renee Gresh, E. Anders Kolb, Ellen Guarnieri, and Mary R. Cooper. 2026. "Leveraging Informatics to Manage Lifelong Monitoring in Childhood Cancer Survivors" Informatics 13, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13020023

APA StyleDavidow, K. A., Gresh, R., Kolb, E. A., Guarnieri, E., & Cooper, M. R. (2026). Leveraging Informatics to Manage Lifelong Monitoring in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Informatics, 13(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13020023