1. Introduction

Technology provides essential support for minority language communities working to preserve and revitalize their endangered linguistic traditions [

1]. Through technological intervention, languages can be documented, electronically stored, and maintained in digital formats [

2]. The increasing availability and accessibility of digital tools—including mobile applications—have provided promising pathways for language preservation, especially for communities experiencing language endangerment.

In recent years, mobile applications have become powerful tools in the global movement toward language revitalization. These technologies support the use of indigenous languages in new communicative domains and foster connections among diverse speakers [

3,

4]. Social media and mobile platforms infuse minority languages with renewed relevance and broaden their linguistic functions and audience [

5]. This digital shift is especially significant for indigenous peoples, whose languages are under-documented and underutilized in contemporary settings.

One such community in the Philippines is the Higaonon, an indigenous group primarily residing in the northern and central parts of Mindanao [

6]. As with many indigenous languages, the Higaonon language is at risk due to several interrelated factors, including generational language shift, limited documentation, and a scarcity of educational materials in the Higaonon Language [

7]. Despite these challenges, the Higaonon people express strong cultural pride and a desire to preserve their language, which plays a vital role in their identity and oral traditions.

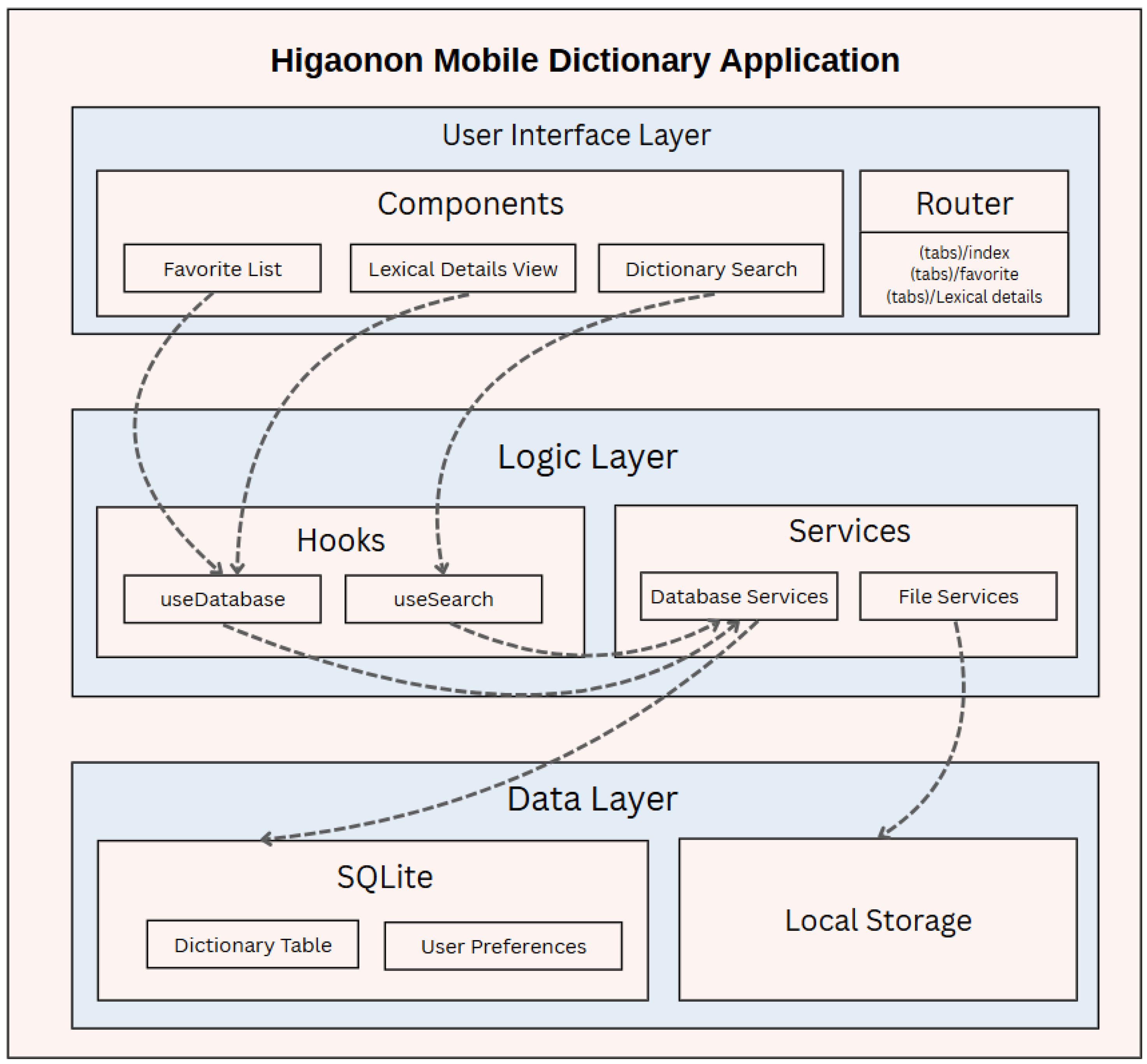

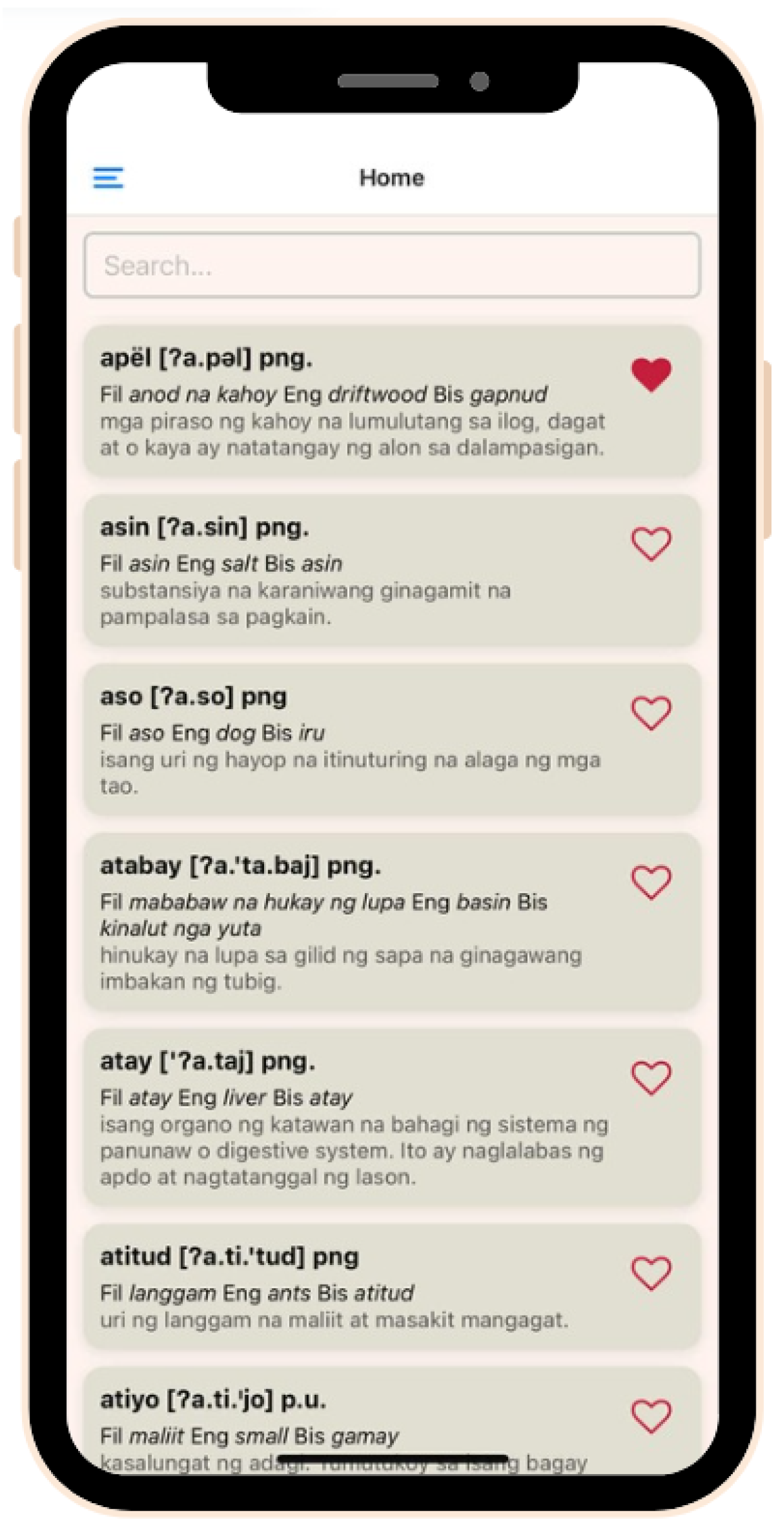

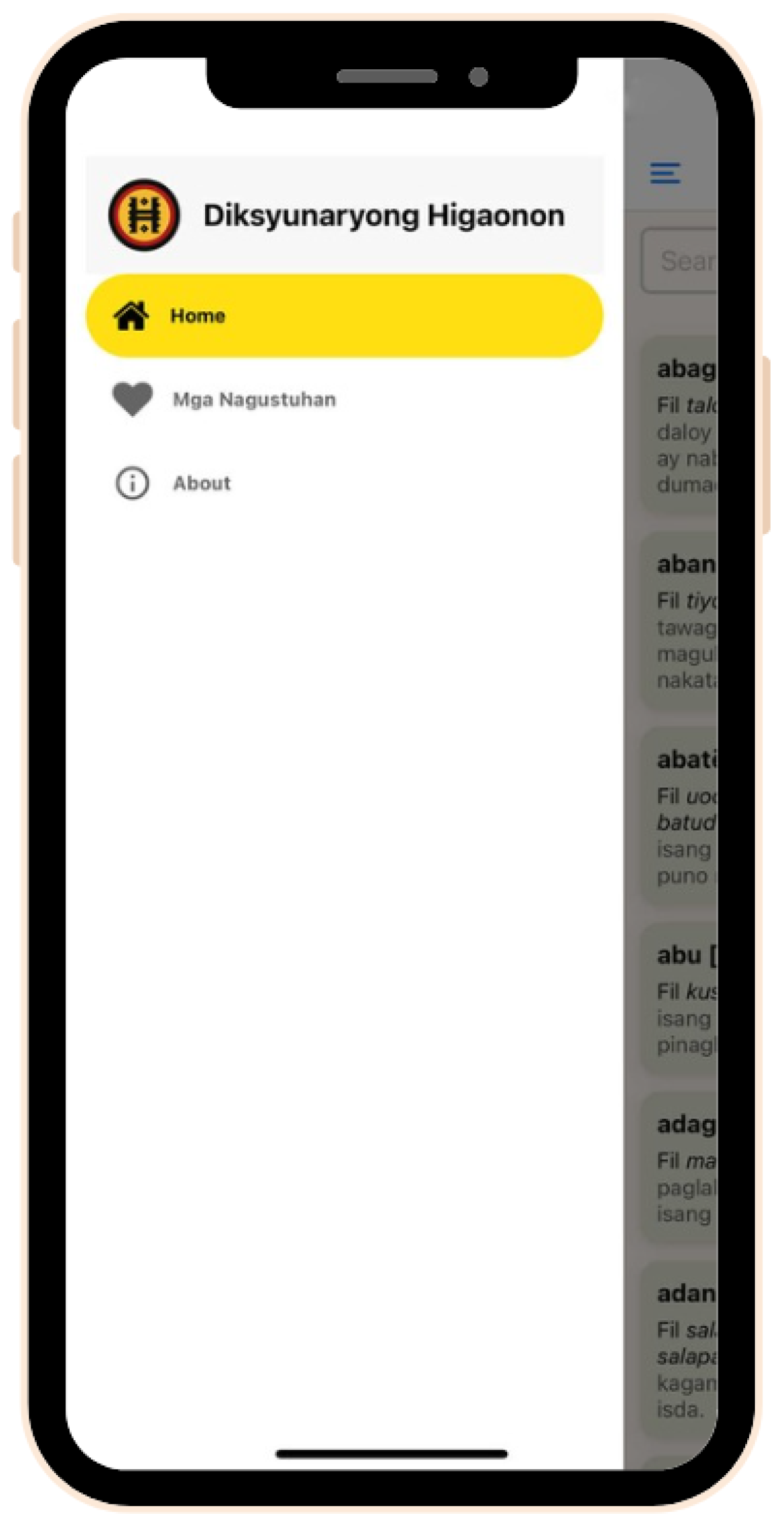

The integration of mobile technology—specifically through a multi-lingual dictionary application—offers a feasible and culturally sensitive solution to address the risk of language loss. Such applications allow community members, educators, and learners to access Higaonon vocabulary, pronunciation, and usage examples regardless of time and place. This mobile approach supports language learning and revitalization efforts, especially among younger generations who are digitally native and often more exposed to dominant languages. According to Cajetas [

7], Higaonon communities confirms that learning their language “helps preserve the language and Indigenous culture” while fostering cultural pride through language preservation. Digital language preservation initiatives have proven successful for other indigenous communities through various interactive formats, including multimedia resources that incorporate audio recordings and culturally relevant materials [

3].

Furthermore, according to Statista [

8], the Philippines has approximately 76.7 million smartphone users, with a substantial portion of youth and adults spending several hours daily on their devices for communication and information access. This widespread adoption of mobile technology presents an opportunity to harness familiar digital platforms for educational advancement and cultural preservation initiatives.

Despite the recognized potential of digital technologies for language preservation, no comprehensive digital dictionary or mobile application has been developed specifically for the Higaonon language prior to this study. While limited efforts have documented Higaonon vocabulary in academic publications [

6,

7,

9], these remain confined to scholarly contexts and lack the accessibility and interactive features necessary for community-wide language learning and revitalization. Similarly, although digital language preservation initiatives have been implemented for other Philippine indigenous languages—such as basic word lists for Ilocano and Tagalog available through government portals—these resources are primarily static repositories rather than dynamic learning tools designed with community input and cultural sensitivity. The absence of dedicated technological resources for Higaonon represents a significant gap in indigenous language preservation efforts in the Philippines, particularly given the language’s vulnerable status and the community’s expressed desire for accessible learning materials.

In 2023, the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF)—the national agency tasked with protecting and promoting the country’s languages—developed the official Higaonon orthography, Ortograpiya ha Hinigaunon. While this represents an important milestone, it does not fully address the broader need for comprehensive studies and resources to support the preservation and revitalization of the Higaonon language [

10]. This study addresses two primary research questions that guide the investigation: (1) How can a mobile dictionary application be designed and developed to preserve and revitalize the Higaonon language through community-centered approaches? (2) How do Higaonon and non-Higaonon users perceive and evaluate the mobile application’s functionality, usability, and performance? The contribution of this research lies in demonstrating how digital technologies and their innovations can protect language as intangible cultural heritage while simultaneously empowering indigenous communities through culturally grounded technological solutions. This study provides empirical evidence that user-centered and culturally responsive approaches to developing digital technologies such as mobile dictionaries can effectively support the preservation of endangered Philippine and global languages, particularly those from marginalized communities.

Specifically, this work contributes to the growing field of indigenous language preservation by documenting the complete development process of a community-driven mobile dictionary application, from initial community consultation through technical implementation and user evaluation. The research establishes a framework for ethical indigenous language documentation that prioritizes community self-determination and cultural intellectual property rights. Additionally, the comparative evaluation between native and non-native users provides insights into how different stakeholder groups experience and assess culturally specific language technologies, informing future development of similar preservation tools. The Higaonon mobile dictionary represents a practical application of digital preservation principles that addresses the immediate needs of an endangered language community while serving as a replicable model for similar initiatives with other indigenous languages facing comparable threats to their linguistic survival. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to help preserve and strengthen the Higaonon language by developing a multi-lingual mobile dictionary app specifically designed for the needs and context of the Higaonon community.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

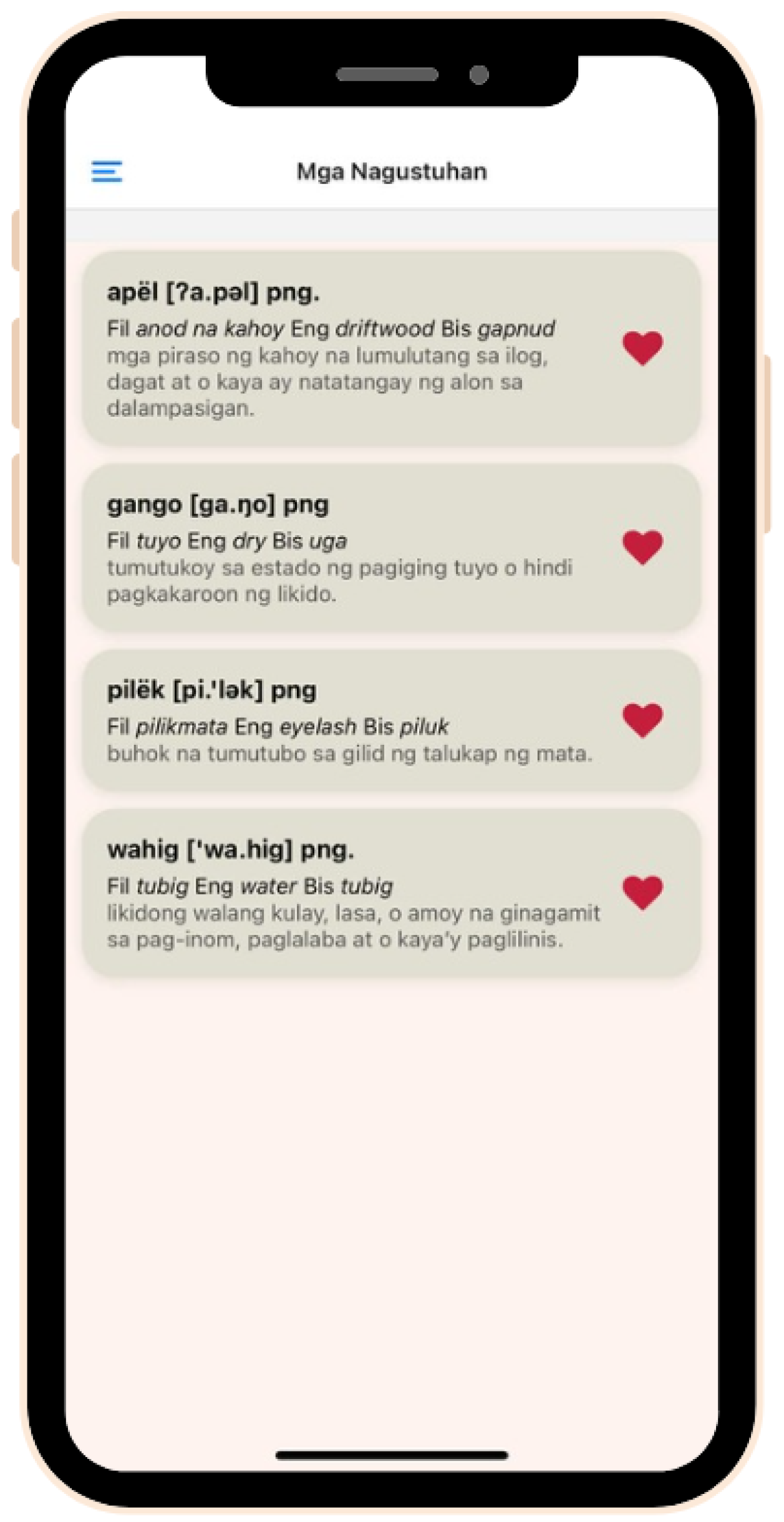

This study contributes to the growing body of research on indigenous language preservation through digital technologies by developing and evaluating a mobile dictionary application for the Higaonon language. The findings demonstrate that strategically designed mobile applications can support language revitalization while honoring indigenous knowledge systems and cultural practices. The Higaonon dictionary integrates linguistic documentation with user-friendly mobile technology, creating an accessible tool for both community members and external stakeholders. High evaluation scores across all dimensions (overall mean of 4.73/5.0) confirm that the application meets its intended purpose while addressing users’ practical needs. Particularly noteworthy is the unanimous approval of the offline access feature (100% agreement), which responds to both technological constraints in indigenous communities and cultural concerns about linguistic intellectual property protection.

At the same time, several limitations must be acknowledged. The small sample size (n = 30) limits generalizability, and the use of convenience sampling prevents broader population inferences. The evaluation emphasized initial user satisfaction rather than long-term learning outcomes or sustained adoption, and the absence of formal statistical testing means observed group differences should be interpreted descriptively rather than seen as statistically significant.

The comparative analysis between Higaonon and non-Higaonon users revealed meaningful differences in how stakeholder groups experienced the application. Native speakers provided more varied and critical feedback—particularly on font readability and performance optimization—reflecting their deeper engagement with linguistic authenticity and cultural representation. These findings underscore the importance of inclusive design processes that center indigenous perspectives rather than relying primarily on external validation.

Beyond serving as a functional dictionary, the application acts as a digital repository of cultural knowledge embedded in language. The integration of cultural symbolism in interface design and the documentation of contextual word usage support preservation not only of vocabulary but also of associated cultural concepts and practices. This holistic approach reflects indigenous educational philosophies that view language as inseparable from cultural identity and worldview.

Building on the evaluation findings, this study proposes a phased roadmap for continued development:

Phase 1 (3–6 months): Focus on technical refinements, including improved font rendering with adjustable sizing, performance optimization for entry-level devices, and enhancements to navigation and scrolling responsiveness. Follow-up testing with original participants should validate these improvements.

Phase 2 (6–12 months): Emphasize content expansion by adding specialized cultural and ecological terminology, audio pronunciations recorded by community elders, and richer example sentences. This phase requires deeper community engagement and may involve additional funding.

Phase 3 (12–18 months): Prioritize community integration through elder engagement protocols, pilot integration with indigenous education programs, community-led maintenance procedures, and extended usage studies to assess long-term adoption.

Phase 4 (18–24 months): Document replicable methodologies, conduct broader evaluations with larger and more diverse samples, assess language learning outcomes, and explore partnerships to extend the approach to other endangered languages.

This roadmap balances resource constraints with concrete directions for sustainable advancement, emphasizing community ownership and respect for indigenous self-determination.

To ensure long-term sustainability, capacity-building initiatives should be implemented among Higaonon youth to develop the skills necessary for managing and updating the digital content. Moreover, application updates must consistently follow established protocols to maintain compatibility, security, and reliability over time.

Future research should address the study’s limitations through larger-scale evaluations, longitudinal designs, and more robust statistical analyses. Examining actual language learning outcomes, adoption patterns, and sustainability models would provide deeper insights into the application’s role in language revitalization. Overall, the study offers proof-of-concept evidence and a methodological foundation for culturally responsive indigenous language technologies, demonstrating that technical design can advance linguistic preservation while safeguarding cultural integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A., P.B.J., S.N.P., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; methodology, D.A., P.B.J., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; software, P.B.J.; validation, D.A., P.B.J., S.N.P., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; formal analysis, D.A. and P.B.J.; investigation, D.A., P.B.J., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; resources, D.A., P.B.J. and S.N.P.; data curation, D.A., P.B.J., S.N.P., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A., P.B.J., S.N.P., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; writing—review and editing, D.A., P.B.J., S.N.P., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; visualization, D.A. and P.B.J.; supervision, D.A.; project administration, D.A., J.R.G.A. and J.O.; funding acquisition, D.A., P.B.J., S.N.P., J.R.G.A. and J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research, including the article processing charge (APC), was funded by the Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology through the Office of Research Management, under the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Enterprise (S.O. 00265-2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the required ethical standards, and ethics approval was obtained from the Research Integrity and Compliance Office of Mindanao State University–Iligan Institute of Technology on 17 February 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. A Certification of Precondition (Informed Consent) was issued by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP), in compliance with Republic Act No. 8371 (Control No. CP-R10-2023-017, issued on 22 November 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Evaluation Questionnaire

Your participation in this study is voluntary, and you may withdraw at any time without penalty. All responses will be kept confidential and used solely for research purposes. Please answer each item honestly; there are no right or wrong answers. By completing this questionnaire, you are giving your informed consent in line with research ethics in the Philippines.

Name: ________________ Gender: ________________ Ethnic Group: ________________

Background Information

How well do you understand the Higaonon?

◯ No understanding ◯ Beginner ◯ Intermediate ◯ Advanced ◯ Native Speaker

How often do you use the Higaonon in daily life?

◯ Never ◯ Rarely ◯ Sometimes ◯ Often ◯ Always

Functionality

The app allows me to quickly find words without difficulty.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The search results are relevant and accurate.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The app provides offline access to definitions.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The app suggests words when I mistype a query.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

I find the “Favorites” feature useful.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

Usability

The app’s interface is intuitive and easy to navigate.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The font size and text formatting enhance readability.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The search bar is easily accessible and well-placed.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The app allows smooth back-and-forth navigation between words.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

Performance

The app loads quickly and does not lag.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

Scrolling through definitions is smooth and responsive.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

The app does not crash or freeze frequently.

◯ Strongly Disagree ◯ Disagree ◯ Neutral ◯ Agree ◯ Strongly Agree

References

- Ariyani, F.; Putrawan, G.E.; Riyanda, A.R.; Idris, A.R.; Misliani, L.; Perdana, R. Technology and minority language: An Android-based dictionary development for the Lampung language maintenance in Indonesia. Tapuya Lat. Am. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2022, 5, 2015088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, Y.A.; Oladokun, B.D.; Olarongbe, S.A.; Amaechi, M.N.; Rabiu, N.; Bashorun, M.T. Revitalizing Indigenous Knowledge Systems via Digital Media Technologies for Sustainability of Indigenous Languages. Preserv. Digit. Technol. Cult. 2024, 53, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meighan, P.J. Decolonizing the digital landscape: The role of technology in Indigenous language revitalization. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2021, 17, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, C.K. Indigenous language revitalization, promotion, and education: Function of digital technology. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 1137–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Irmies, A.J.; Al-Khanji, R.R. The Role of Social Media in Maintaining Minority Languages: A Case Study of Chechen Language in Jordan. Int. J. Linguist. 2019, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balangiao, M.V.O.; Walag, A.M.P. Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Practices of Higaonon Tribe from Mat-i, Claveria, Philippines. SDSSU Multidiscip. Res. J. 2022, 10, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajetas-Saranza, R. Higaonon Oral Literature: A Cultural Heritage. US-China Educ. Rev. B 2016, 6, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Number of Smartphone Users in the Philippines from 2020 to 2029 (in Millions). 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/467186/forecast-of-smartphone-users-in-the-philippines/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Abatayo, J.V.C.S.; Gumapang, D. Cultural Activities, Resources, Practices, and Preservation of the Higaonon Tribe: An Ethnographic Study. New Educ. Rev. 2024, 77, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino. Ortograpiya ha Hinigaunon: Ortograpiyang Hinigaunon; Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino: Manila, Philippines, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Peoples of the Philippines: Manobo. 2025. Available online: https://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/culture-profile/glimpses-peoples-of-the-philippines/manobo/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Pandapatan, A.M.; Ali, A.A.; Macarambon, A.T.; Altamia, C.G.; Ramos, N.U.; Hadji Socor, N.U.; Abaton, S.Z.A.; Pantao, A.G. Cultural Challenges and Preservation: The Case of Higaonon of Rogongon, Iligan City. Glob. Sci. J. 2024, 12, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels, A. Language Maintenance and Shift; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Linguistics, University of the Philippines Diliman. Counter-Babel: Reframing Linguistic Practices in Multilingual Philippines. 2021. Available online: https://linguistics.upd.edu.ph/news/counter-babel-reframing-linguistic-practices-in-multilingual-philippines/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Alejan, J.A.; Ayop, J.I.E.; Allojado, J.B.; Abatayo, D.P.B.; Abacahin, S.K.N.; Bonifacio, R. Beyond extinction: Preservation and maintenance of endangered indigenous languages in the Philippines. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2021, 10, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, S. Language Shift and Language Maintenance in Indonesia. In Language, Education and Nation-Building; Sercombe, P., Tupas, R., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in Minority Languages and Communities; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. DO 62, s. 2011—National Indigenous Peoples Education Policy Framework.; 2011. Available online: https://www.deped.gov.ph/2011/08/08/do-62-s-2011-adopting-the-national-indigenous-peoples-ip-education-policy-framework/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Department of Education. DO 16, s. 2012—Guidelines on the Implementation of the Mother Tongue-Based-Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE).; 2012. Available online: https://www.deped.gov.ph/2012/02/17/do-16-s-2012-guidelines-on-the-implementation-of-the-mother-tongue-based-multilingual-education-mtb-mle/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Akintayo, O.T.; Atobatele, F.A.; Mouboua, P.D. The dynamics of language shifts in migrant communities: Implications for social integration and cultural preservation. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 6, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundziuvienė, D.; Cvilikaitė-Mačiulskienė, J.; Matulionienė, J.; Matulionytė, S. The Role of Languages and Cultures in the Integration Process of Migrant and Local Communities. Sustain. Multiling. 2020, 16, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, D.M.; Simons, G.F.; Fennig, C.D. (Eds.) Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 28th ed.; SIL International: Dallas, TX, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Science and Technology, Philippines. DOST Funded Mangyan Language App to Preserve a Dying Language. 2022; Press Release. Available online: https://www.dost.gov.ph/knowledge-resources/news/74-2022-news/2690-dost-funded-mangyan-language-app-to-preserve-a-dying-language.html (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Carreon, M.; Sadural, S. Project Marayum: A Community-Built Online Dictionary for Endangered Philippine Languages; University of the Philippines Diliman: Quezon, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sihite, M.R.; Sibarani, B. Technology and language revitalization in Indonesia: A literature review of digital tools for preserving endangered languages. Int. J. Educ. Res. Excell. (IJERE) 2024, 3, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, M.; Bang, M.; Marin, A. Designing Indigenous language revitalization. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2012, 82, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, M. Mobile apps and Indigenous language learning: Review and perspectives. Work. Pap. Linguist. Circ. Univ. Vic. 2016, 26, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Republic Act No. 8371. The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997. Supreme Court E-Library. 1997. Available online: https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/2/2562 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. Administrative Order No. 01, Series of 2012: The Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practices (IKSPs) and Customary Laws (CLs) Research and Documentation Guidelines; World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Philippine Health Research Ethics Board and National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. Memorandum No. 2017-001: Ethical Guidelines for Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples; Philippine Health Research Ethics Board: Taguig, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. Administrative Order No. 3, Series of 2012: The Revised Guidelines on Free and Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) and Related Processes of 2012; National Commission on Indigenous Peoples: Quezon, Philippines, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mosel, U. Lexicography in endangered language communities. In The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages; Austin, P.K., Sallabank, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, P.K. Language Documentation and Language Revitalization. In Revitalizing Endangered Languages; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongsubanan, S.; Kasemsarn, K. Developing a design guideline for a user-friendly home energy-saving application that aligns with user-centered design (UCD) principles. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 7424–7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design; Nielsen Norman Group: Dover, DE, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Bao, J.; Setiawan, I.M.A.; Saptono, A.; Parmanto, B. The mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (MAUQ): Development and validation study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichbroth, P. Usability Testing of Mobile Applications: A Methodological Framework. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Flood, D.; Duce, D. Usability of mobile applications: Literature review and rationale for a new usability model. J. Interact. Sci. 2013, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehle, H.; Aljafari, R.; Venkatesh, V. Leveraging Microsoft’s mobile usability guidelines: Conceptualizing and developing scales for mobile application usability. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2016, 89, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.D.; Al Hatef, E.A.J. Types of Sampling and Sample Size Determination in Health and Social Science Research. J. Young Pharm. 2024, 16, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, A.; Sjoblom, E.; Sinclair, S.; Cidro, J. A New Era of Indigenous Research: Community-based Indigenous Research Ethics Protocols in Canada. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2021, 16, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagal-Bustillo, R.C.; Tiongson, G.; Remorosa, R. Utilizing Educational Technology For The Preservation And Revitalization Of Indigenous Language And Culture: A Research Investigation. Int. J. Res. Publ. 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goce, E.C. The Higaonon cultural identity through dances. PNU President’s Research 2005, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Paluga, M.D. Indigenous Archaeology in the Philippines: Decolonizing Ifugao History, by Stephen B. Acabado and Marlon M. Martin. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde/J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Southeast Asia 2023, 179, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Zelenko, O.; Tjondronegoro, D.; Mani, M. Mobile App Rating Scale: A New Tool for Assessing the Quality of Health Mobile Apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015, 3, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palas, J.U.; Sorwar, G.; Hoque, M.R.; Sivabalan, A. Factors influencing the elderly’s adoption of mHealth: An empirical study using extended UTAUT2 model. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramba, I.; Chatterjee, A.; Newman, C. Methods of usability testing in the development of eHealth applications: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 126, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Santosa, P.I.; Hartanto, R. Usability Evaluation Methods of Mobile Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Information Technology and Digital Innovation (ISITDI), Padang, Indonesia, 27–28 July 2022; pp. 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddin, Z.; Saeedi, Z.; Mozaffari, H. Native and Non-native Language Teachers’ Perspectives on Teacher Quality Evaluation. Teach. Engl. Second. Or Foreign Lang.–TESL-EJ 2023, 27, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraz, M.; Ali, M.; Excell, P.S. Cross-cultural usability evaluation of AI-based adaptive user interface for mobile applications. Acta Sci. Technol. 2022, 44, e61112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

_Bryant.png)