Abstract

E-government and transparency are significantly improving public service management by encouraging trust, accountability, and the massive participation of citizens. On the one hand, e-government has facilitated online services to address bureaucratic processes more efficiently. On the other hand, transparency has promoted open access to public information from the State so that citizens can understand and track aspects of government processes more effectively. However, as both require extensive citizen information management, these initiatives may significantly compromise privacy by exposing personal data. To assess these privacy risks in a concrete scenario, we analyzed 21 public institutions in Ecuador through a proposed taxonomy of 6 categories and 17 subcategories of disclosed personal data on their online portals and websites due to LOTAIP transparency initiative. Moreover, 64 open-access systems from these 21 public institutions that accomplish e-government principles were analyzed through a proposed taxonomy of 8 categories and 77 subcategories of disclosed personal data. Our results suggest that personal data are not handled through suitable protection mechanisms, making them extremely vulnerable to manual and automated exfiltration attacks. The lack of awareness campaigns in Ecuador has also led many citizens to handle their personal data carelessly without being aware of the associated risks. Moreover, Ecuadorian citizens’ privacy is significantly compromised, including personal data from children and teenagers being intentionally exposed through e-government and transparency initiatives.

1. Introduction

Governments today rank among the principal aggregators of high-quality personal data. By law, they collect vast amounts of data on their populations, covering areas such as biometrics, demographics, health, and economics, from birth through death [1]. Individuals are required to provide the State with continuously updated data, in perpetuity, to be recognized as functional citizens and to acquire the corresponding rights and obligations. This information is vast and validated, ensuring a high level of quality, which is critical for extracting valuable insights. All these data enable governments to make more informed decisions, enhancing their ability to serve the population effectively.

Sadly, there are several privacy risks involved in this context. First, citizens’ data are provided to the State by default, lacking an opt-out option similar to those available in, for example, social networks. In addition, there are serious risks of misuse, unauthorized access, and function creep (where data are used for purposes beyond their original intent). Finally, the State is a single point of failure holding sensitive personal data on entire populations [2].

To compound matters further, these privacy risks are exacerbated for a number of reasons. Not only does the State collect vast quantities of personal data, but these data must also be managed and processed for diverse purposes—such as enforcing regulations or facilitating online services to make administrative procedures more accessible [3]. In this context, efforts to increase State transparency have led public administrations to openly publish much information about institutions; their employees; and, to some extent, the citizens themselves. Likewise, numerous online platforms have been deployed to consolidate, process, and distribute this information, supporting ambitious e-government initiatives aimed at enabling citizens to interact more efficiently and effectively with bureaucracy [4]. Consequently, though with laudable intentions, personal data are frequently exposed, at times with absolutely no control. As if this were not enough, the interaction of everyday citizens with such platforms introduces an additional layer of risk, as privacy novices may inadvertently jeopardize the security of their data by handling them carelessly [5]. Thus, privacy becomes vulnerable even in the absence of an external attacker.

1.1. Ecuador: A Different Perspective on Privacy Research

Ecuador is a very small Latin American country, a developing nation, that has undergone many political, economic, social, legal, and even technological changes in recent years. As in other countries within the region, these changes often differ significantly from those encountered by most developed nations [6]. Thus, focusing on Ecuador is particularly relevant for privacy studies, as it provides insights distinct from those obtained by concentrating on more developed regions (e.g., USA, Europe, and China), which are characterized by stability and well-established data protection legislation. Consequently, analyzing the Ecuadorian context can provide a new perspective and help understand the challenges of data protection in other geographies with different development conditions.

In Ecuador and several Latin American countries, awareness of online privacy is very limited, unlike in other regions where it is a sensitive and high-priority issue [7]. Cultural, economic, and even language-related factors likely influence the attitudes of various stakeholders toward the concept of privacy [8]. Given that this is the reality for a significant portion of the global population (mainly Latin America and Africa), it is essential to study these contexts.

On the other hand, despite its challenges, Ecuador has made significant progress in Internet access, digitalization, transparency, and data protection [9]. For instance, Ecuador has recently enacted a privacy regulation inspired by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This late initiative brings an opportunity to study the effectiveness and impact of such regulations in an unexplored context like Latin America, and to identify the gaps between legislation and its enforcement. This analysis is necessary to unveil the real challenges faced by societies in protecting privacy.

Furthermore, for more than a decade, Ecuador has implemented an aggressive digitalization strategy in the public sector, aimed at improving citizen services [10]. In this line, anti-corruption efforts have significantly increased public sector transparency, providing broader access to State information. However, these services were implemented without prioritizing the privacy or protection of personal data. As is known, the rapid deployment of online services often overlooks security and privacy concerns, which could worsen within the next 20 years, especially in contexts with less reliable institutions and pressing socioeconomic challenges. In this context, studying online privacy in Ecuador can contribute to the academic literature by exploring how developing countries can protect the digital rights of their citizens while advancing toward increasingly connected societies.

1.2. Contribution

This research outlines a privacy assessment framework for unveiling risks in a scenario of attack that might not even consider the presence of an active adversary but rather reveals privacy breaches that arise from the implementation of aggressive e-government and transparency initiatives, e.g., privacy breaches by design. To the best of our knowledge, this problem has not been addressed deeply before in Ecuador. Moreover, previous studies in other countries often rely on citizens’ perception assessments when using online services due to e-government initiatives, gathering insights based on their feelings and experiences through surveys and questionnaires. This method is highly prone to error as it is subjective and biased by each individual’s opinion. Therefore, this research is based on evidence through the analysis of information collected from websites and open-access systems. Table 1 summarizes these previous studies, detailing their advantages and disadvantages.

Table 1.

A comparison of this research with previous studies carried out for other countries.

In addition, the focus on Ecuador provides a distinctive approach to privacy and data protection, as it constitutes a highly specific regulatory and technological landscape. This perspective highlights the unique challenges and opportunities in addressing data governance, compliance, and cybersecurity risks in underexplored geographies. For instance, given the recent enforcement of privacy regulations, it is possible to conduct a granular analysis of their impact on vulnerability management and risk assessment methodologies. Additionally, the implementation of secure cipher channels for data transmission; the strengthening of authentication, authorization, and auditory protocols; and the adoption of zero-trust architectures are critical considerations in mitigating data exfiltration threats and unauthorized access across different sectors of society.

In other words, this study addresses a critical gap in the literature by providing a structured framework to examine privacy challenges in volatile and rapidly evolving threat landscapes. It not only enhances the understanding of data protection risks and vulnerabilities in Ecuador but also contributes to global cybersecurity discourse by offering transferable insights for societies undergoing digital transformation, regulatory adaptation, and networked infrastructure expansion. This perspective emphasizes the importance of including underrepresented regions in global privacy and cybersecurity discussions, particularly in paramount areas such as risk-based access control (RBAC), secure cipher channels for data transmission, and adaptive threat modeling. By integrating less-explored environments into regulatory and technological frameworks, the study promotes a more holistic approach to privacy governance, incident response, and resilience against emerging cyberthreats.

In this paper, privacy breaches resulting from this contradictory scenario are analyzed. Section 2 details the roadmap to e-government, transparency, and privacy in Ecuador. Section 3 describes the applied methodology, while Section 4 presents and analyzes the results obtained. In Section 5, a discussion is presented, and in Section 6, the conclusion reached in this research is presented.

2. The Ecuadorian Roadmap to E-Government, Transparency, and Privacy

2.1. The Pursuit of E-Government and Transparency

E-government primarily aims to enhance citizens’ access to information and online services through the strategic use of technology [19]. Ecuador has achieved notable advancements in e-government and transparency initiatives, which have been widely recognized and appreciated by its citizens. These efforts have significantly enhanced public access to governmental services and information, thus fostering a more transparent and efficient administrative framework [20].

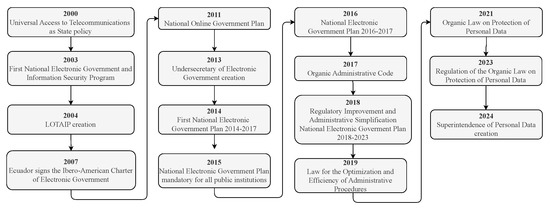

In Ecuador, this initiative was officially launched in 2000, when universal access to telecommunications services—critical channels for public engagement with e-government tools—was established as a State policy [21]. This foundational move was instrumental in enabling the development of digital governance platforms, facilitating more efficient and transparent interactions between the State and its citizens.

In 2003, the first National Electronic Government and Information Society Program was published with the components definition of policies and implementation of infrastructure projects [21]. In 2007, Ecuador signed the Ibero-American Charter of Electronic Government, which aims to guarantee citizens transparency in public administrations, optimize processes, improve access to information, and encourage active participation [21]. Also, the Undersecretary of Informatics was created during this year to improve government management through the implementation of information technology projects. In 2011, the National Online Government Plan was proposed to promote digital services for citizens, governments, and companies, promoting citizenship access to information and public services, for example, through online portals and websites [22]. In this sense, the Undersecretary of Electronic Government was created in 2013 to support the implementation of e-government in public administration. As part of this initiative, several mechanisms were defined to simplify procedures. In 2014, the first National Electronic Government Plan 2014–2017 was launched with more than 100 programs, projects, and regulations [23].

In 2015, the mandatory implementation of the National Electronic Government Plan was provided for all State institutions and dependent organizations on the Ecuadorian executive function. In 2016, the publication of the National Electronic Government Plan 2016–2017 was made official, whose objectives included increasing access to electronic services and improving the level of access to public information, as well as the efficiency, effectiveness, and performance of public institutions [24]. In the same way, the Organic Administrative Code provided the adoption of electronic government instruments in 2017. In 2018, regulatory improvement and administrative simplification of procedures were proposed as a State policy [25]. Also, the National Electronic Government Plan 2018–2021 was issued during this year [26]. Finally, in 2019. the Law for the Optimization and Efficiency of Administrative Procedures was promulgated, which guarantees the implementation of online procedures whenever possible.

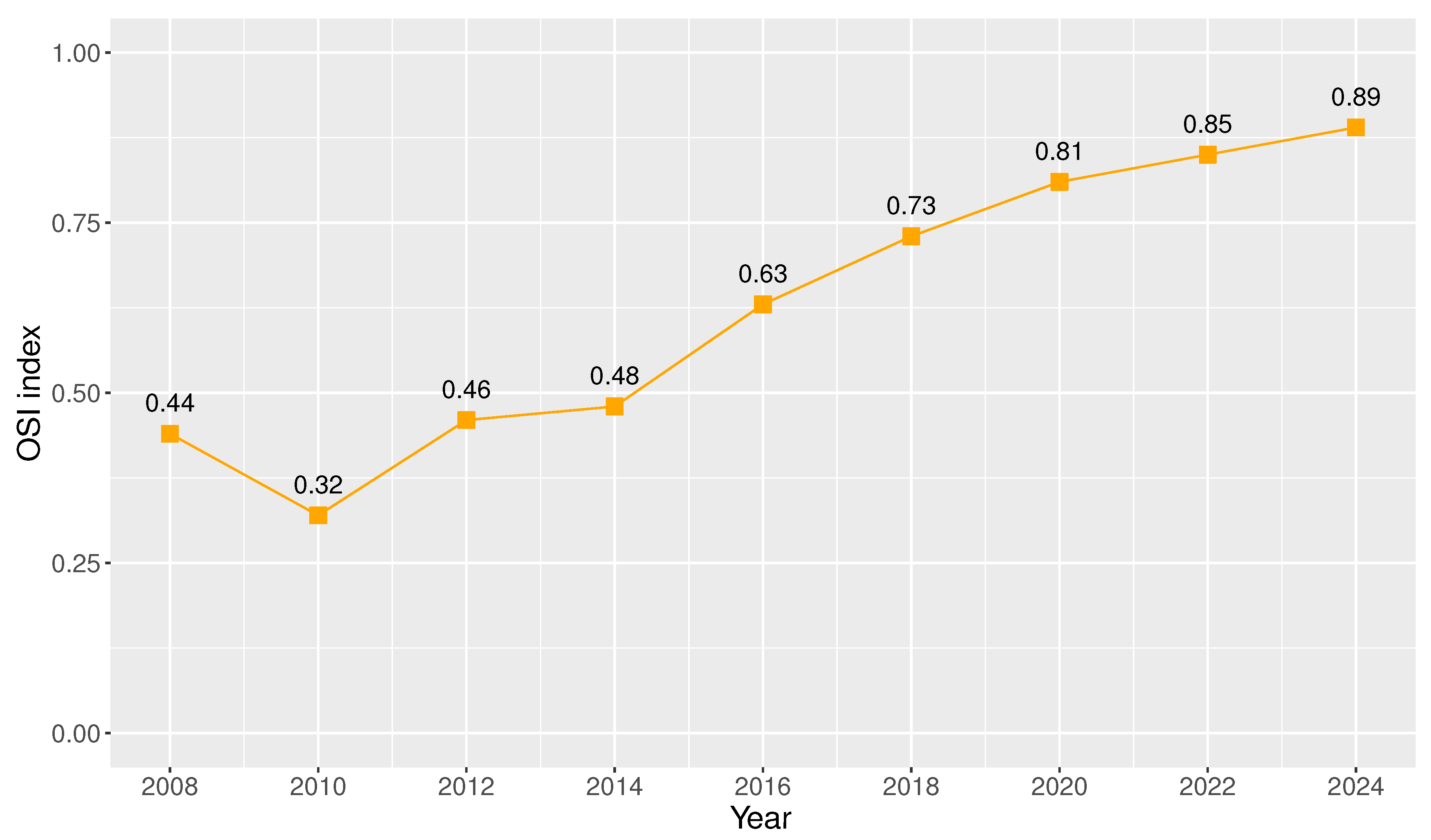

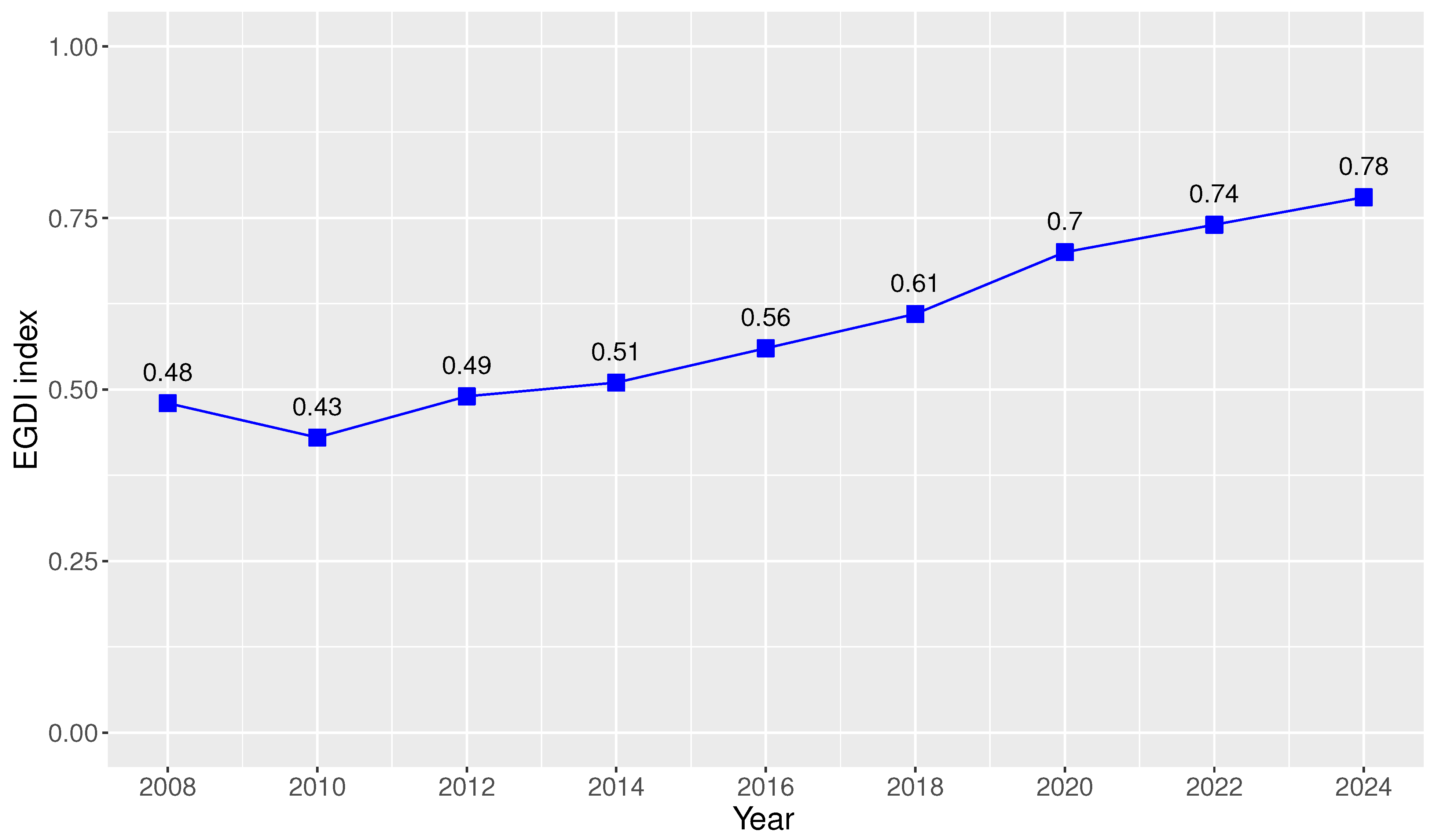

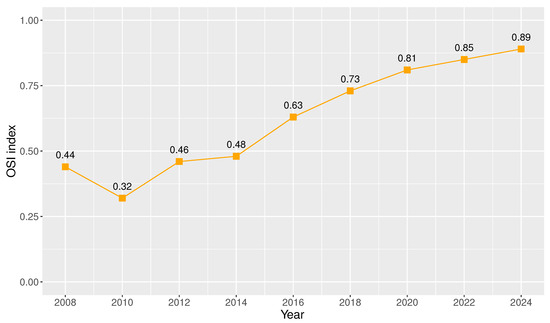

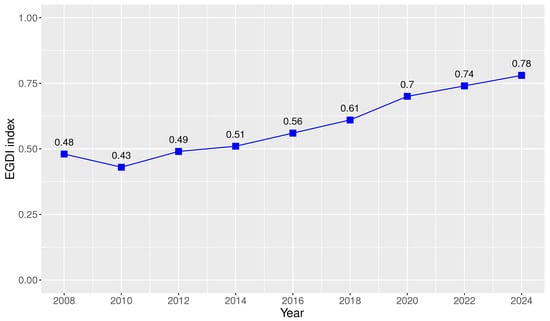

As part of this initiative, the Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Society (MINTEL, which stands for Ministerio de Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información) created the Single Portal for Citizen Procedures Gob.ec available at [27], which includes a detailed and centralized list of procedures offered by public institutions in Ecuador to citizens, as well as an Application Programming Interface (API) that allows the direct interconnection among MINTEL and the technological platforms of these public institutions to share information, streamline processes, and reduce service times. Due to these significant efforts, Ecuador has achieved through time the OSI (Online Service Index) and EGDI (E-Government Development Index) indexes detailed in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively [28]. These indexes reflect the significant advance of Ecuador in e-government initiatives [26,29].

Figure 1.

Ecuador’s OSI index (2008–2024).

Figure 2.

Ecuador’s EGDI index (2008–2024).

On the other hand, transparency in Ecuador has been mainly managed from 2004 through the Organic Law of Transparency and Access to Public Information (LOTAIP, which stands for Ley Orgánica de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública). In order to help curb corruption and fraud in Ecuador, as well as increase responsibility and participation between the Ecuadorian State and citizenship, this law guarantees citizens the right to access the information generated and managed by public institutions [30]. Therefore, public institutions are compelled to disclose at their online portals or websites information about their employees and processes, allowing to know how they are managed.

Overall, an Ecuadorian law is formed by a group of articles designed to clearly and concisely provide the guidelines and directives that must be followed. Since certain articles may cover multiple guidelines applicable to different related areas, they also define several subsections known as literals. Each literal outlines specific aspects of the article, providing precise directives that help clarify its purpose for a particular context, thus avoiding ambiguity. Specifically, five literals of LOTAIP Article 7, summarized in Table 2, establish as mandatory the disclosure of information by public institutions including but not limited to personal data belonging to their employees.

Table 2.

LOTAIP Article 7 literals associated with mandatory disclosure of personal data.

Nevertheless, transparency in Ecuador has been promoted as the panacea against corruption by several social sectors [31], allowing Ecuador to raise significant places in the overall Right to Information Rating (holding at the time of writing the worldwide position 76) [32].

2.2. Privacy Regulation in Ecuador

Privacy and personal data have been protected in Ecuador through several regulations. For instance, the Ecuadorian Constitution and a set of several laws related to telecommunications, electronic commerce, and criminal procedures establish measures oriented to protect personal data.

In 2021, the Organic Law on Protection of Personal Data (LOPDP, which stands for Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales) was published in Ecuador and is currently the main mechanism for the protection of citizen privacy. LOPDP main objectives are (1) to guarantee the right to protection of citizens’ personal data and (2) that citizens have access to and can make decisions about their personal data [33]. However, it is worth mentioning that the achievement of these objectives is expected to be reflected in the coming years through the proper execution by public institutions, private companies, and citizens.

The LOPDP does not establish a taxonomy for personal data; however, it distinguishes four categories of sensitive personal data, which, if revealed, would significantly impact its owners. These four categories of sensitive personal data are as follows: (1) Immigration status, (2) Ethnicity, (3) Judicial, and (4) Health.

Although LOPDP is based on GDPR, it has several limitations. One of those limitations, for example, is related to the reduced penalties in comparison to the GDPR. However, the most important limitation is regarding the law’s exceptions for its application, a phenomenon that already occurred with previous legislation. For instance, the Electronic Commerce Law already indicated that consent for data processing is not necessary when its collection is carried out in the context of public administration [34]. Likewise, LOPDP raises several exceptions concerning the privacy rights of users in Ecuador, such as the declaration of personal data of public workers as open data accessible for citizens and entities for data treatment (Article 2). In addition, it provides public workers’ patrimonial history declarations and remuneration details, which constitute sensitive personal data.

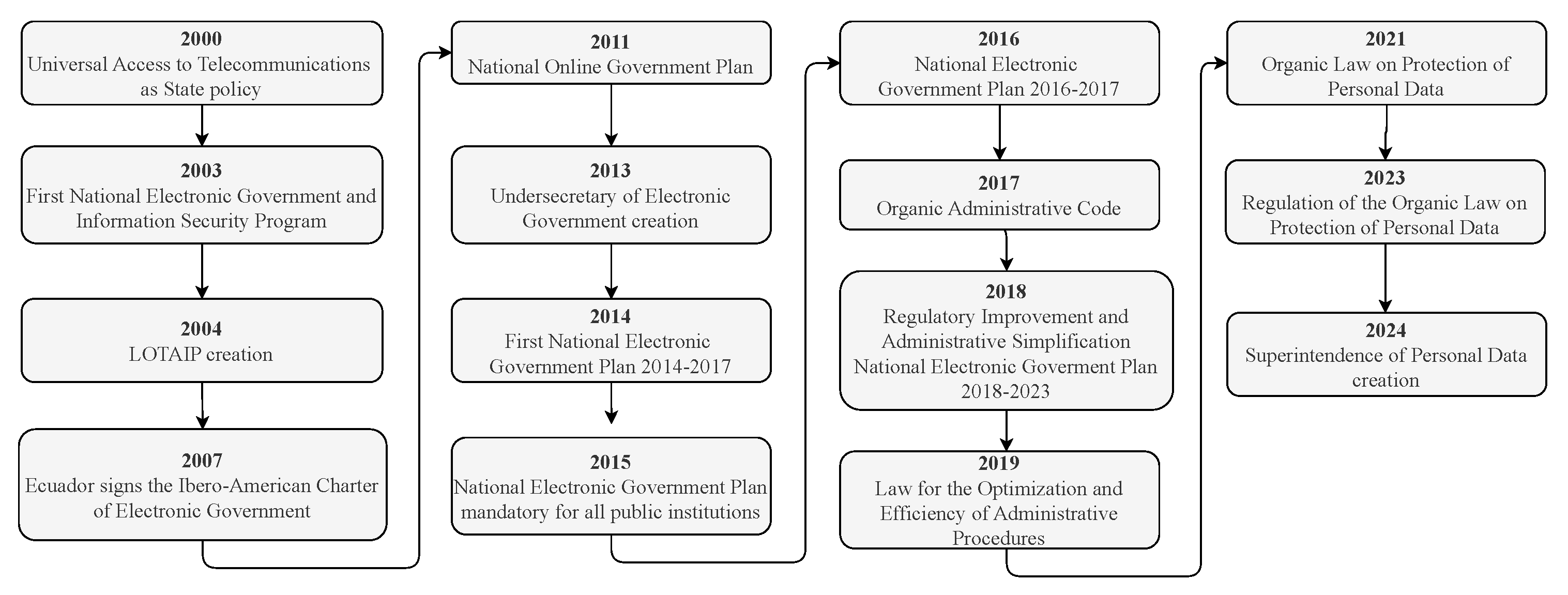

In November 2023, the Regulation of the LOPDP was issued to ensure the correct implementation of the law. This regulation seeks to strengthen data security and confidentiality, establishes the responsibilities of the entities that manage it, and ensures that citizens have control over their personal data. In addition, it seeks to align with international data protection and privacy standards [35]. Furthermore, the Superintendence of Personal Data Protection was created in October 2024 to ensure compliance with the LOPDP and its Regulation, protecting the privacy and security of Ecuadorians’ information. Figure 3 summarizes the milestones in the regulation of e-government, transparency, and privacy in the Ecuadorian context.

Figure 3.

E-government, transparency, and privacy milestones in the Ecuadorian context.

2.3. A Worrisome Outlook in Ecuador

Ecuador has suffered several data leak incidents in recent years, primarily caused by reconnaissance attacks, ransomware attacks, lack of adequate perimeter security, and a lack of a culture of information security and privacy.

Reconnaissance attacks: Reconnaissance and information-gathering attacks on websites and infrastructures have affected public organizations in Ecuador, allowing them to collect sensitive data and serving as a baseline to execute subsequent advanced exploits against privacy such as Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) attacks and backdoors. Moreover, other kind of exploits such as Denial of Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks against systems availability have been executed after a successful reconnaissance attack [36].

In 2024, for instance, the Agencia Nacional de Tránsito (ANT) identified that it had fallen victim to reconnaissance attacks on its technological infrastructure, allowing attackers to collect information such as IP addresses, usernames, and servers’ details, allowing subsequent theft of user credentials, and causing delays in citizens service [37]. In 2025, the Civil Registry reported a cyberattack on its IT systems and website, which is believed to have collected basic information, stolen cookies, and disrupted the appointment scheduling system for issuing Digital Number Identifier (DNI) documents and passports [38].

Ransomware attacks: Ransomware attacks have also been a cause of personal data exfiltration in Ecuador [39]. In 2021, the National Transit Agency (ANT) suffered a data breach in its AXIS system due to a suspected ransomware attack (whose strain could not be identified). This attack also caused service disruptions in the issuance of driver’s licenses and vehicle registrations for extended periods [40].

That same year, the RansomEXX ransomware affected the Corporación Nacional de Telecomunicaciones (CNT), causing not only personal data exfiltration but also preventing users from paying phone, Internet, and television bills and completing certain online or in-person transactions for several days [41]. A similar situation occurred with the Municipio de Quito in 2022, when the BlackCat ransomware massively exfiltrated data from its production and development databases, paralyzing its technological infrastructure [42].

Lack of adequate perimeter security: In 2019, the sensitive information of Ecuadorians held by the consulting firm Novastratech S.A. was severely compromised due to the failure to implement adequate security measures for its protection. The data breach was identified by the cybersecurity company vpnMentor, which alerted Ecuadorian authorities [43]. It was revealed that the data were stored on an unprotected server in Miami, USA, and was publicly accessible. The breach is estimated to have involved 18 GB of personal data, including names, financial information, and civil records of up to 20 million people [44].

As a result of the incident, the urgent approval of the LOPDP law was promoted, and public institutions were encouraged to store their information on their own servers and implement proper perimeter security controls. This latest requirement has had positive effects in recent years. Most public institutions in Ecuador have their secure on-premise technological infrastructure with controls such as Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS), Data Loss Prevention (DLP), Web Application Firewalls (WAF), and Email Security Appliances (ESA). However, it is important to maintain and update the rules of these devices regularly to avoid likely security holes.

Lack of a culture of information security and privacy: The lack of a culture of information security and privacy has been the main trigger for several cyberattacks that have led to massive leaks of Ecuadorians’ personal data. Unfortunately, protective measures were implemented only after a serious incident had occurred. In 2021, for example, the Policía Nacional del Ecuador reported unauthorized access to its Integrated Computer System (SIIPNE 3W) using the credentials of one of its members, exposing sensitive information related to a femicide case [45]. It is presumed that the credentials were not carefully safeguarded by their owner rather than being compromised through a brute-force or dictionary attack. In 2024, the Agencia Metropolitana de Tránsito (AMT) reported a suspected hack of its IT system, which allowed the alteration of approximately 9620 transit procedures in Quito, Ecuador, exposing the personal data of citizens and vehicles. However, it is suspected that rather than an actual system vulnerability, the attack resulted from negligence in access management by the responsible personnel [46].

A final reflection: Security is a complex chain and a single weak link is enough to enable a successful data leak. Our study estimates that more than 75% of personal data leaks in Ecuador are likely caused by threats that take advantage of the lack of a culture of information security and privacy in the Ecuadorian society, creating an ideal scenario for personal data exfiltration. We estimate this percentage based on the number of public access systems due to the e-government initiative that we were able to analyze from the representative sample of 83 systems initially chosen.

Additionally, the lack of encrypted production databases, the use of production database information in software development environments without proper controls, storing sensitive data in plaintext files on servers, the use of personal devices by public institution employees, and paper-based document management with inadequate disposal methods are among the main risk factors contributing to personal data leaks.

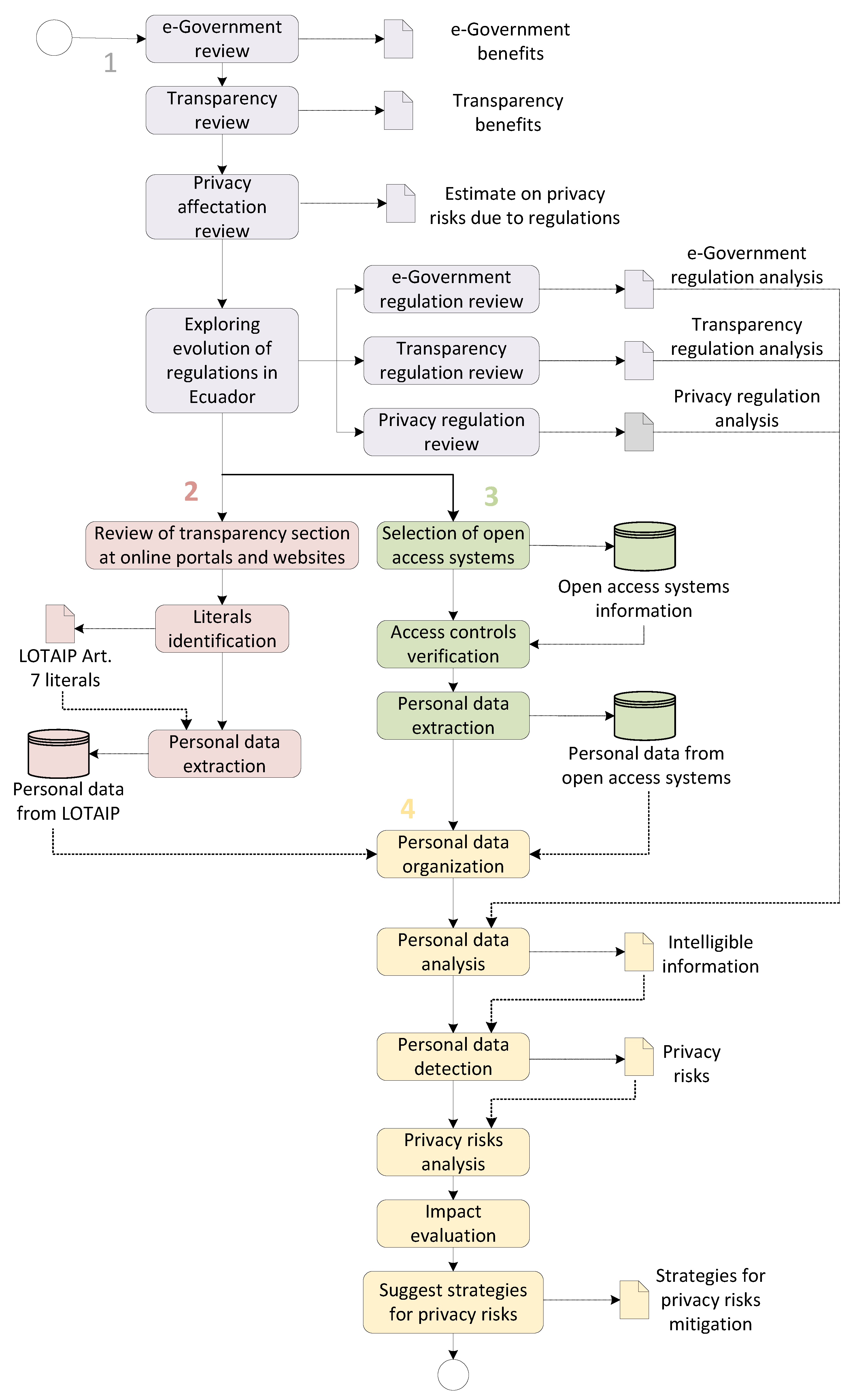

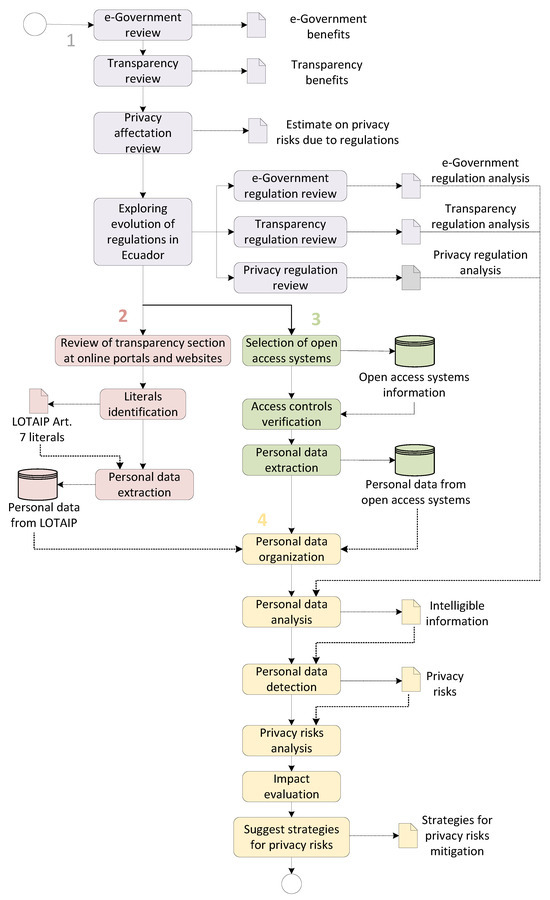

3. Methodology

The research methodology was based on four stages that allowed the identification of privacy risks in Ecuador. Figure 4 illustrates this methodology and shows the information gathered and analyzed in each step.

Figure 4.

Methodology flowchart. Dotted lines lead to the result obtained from executing a determined step (represented in a rectangle), which also serves as input for the next step. The solid lines indicate the next step to be carried out.

In stage 1, we performed a general review of the e-government, transparency, and privacy in Ecuador in order to determine the benefits of e-government and transparency as well as their impact on privacy. This baseline facilitated a subsequent analysis of the regulation and its evolution from each initiative to have a first insight into the associated law in Ecuador.

A deep analysis of LOTAIP was carried out in stage 2. This analysis led to unveiling the parts of the law (Article 7) that explicitly require the disclosure of personal data. The corresponding literals of the law and the information to be disclosed are depicted in Table 2. As a result of the enforcement of this law, public institutions’ websites are filled with personal data associated with public employees. In this research, 21 public institutions between ministries, control entities, municipalities, and institutions that offer popular services in Ecuador were analyzed. Table 3 lists these 21 public institutions.

Table 3.

Number of open-access systems by public institution.

The information disclosed by these 21 public institutions on their online portals and websites was carefully gathered and classified, considering as personal data all information that could identify or be used to identify individuals, either directly or indirectly. Related personal data were then clustered and assigned to a more general personal data subcategory. Finally, resulting subcategories were assigned to a category, allowing the obtainment of compact and easier-to-analyze information. For instance, the personal data Monthly remuneration and Annual remuneration refer to the same subcategory Income of the category Heritage. Table 4, presents a proposed taxonomy of 6 categories and 17 subcategories defined to analyze privacy risks due to the LOTAIP transparency initiative.

Table 4.

Proposed taxonomy of disclosed personal data to analyze privacy risks due to LOTAIP transparency initiative.

A similar strategy was carried out in stage 3, studying the personal data provided by open-access systems. In total, 64 open-access systems belonging to the 21 public institutions were identified and analyzed, as detailed in Table 3. To consider a system as open access, the following criteria were taken into account: (1) the system must be accessible through the Internet; (2) the system must belong to a public institution; (3) the system must provide personal data of citizens through online consultation; (4) the system must not require authentication of the owner of the information.

Some web pages and mobile applications that generate traffic and income through advertising, such as EcuadorLegalOnline [47], Ecuador WEB [48], and Consultas Ecuador [49], serve as gateways to several of these open-access systems. These platforms helped identify most of the open-access systems from the 21 public institutions described in Table 3. The 64 open-access systems identified revealed 111 unique personal data that were consolidated through a proposed taxonomy of 8 categories and 77 subcategories, as detailed in Table 5. While some subcategories can allow identification of the owner of the personal data, others can enable identification of third parties related to the owner and even their relatives. The Health and Judicial categories of sensitive personal data in the LOPDP directly correspond to the categories of the same name detailed in Table 5, while Immigration status and Ethnicity correspond to the subcategories of the same name within the Demography category.

Table 5.

Proposed taxonomy of disclosed personal data to analyze privacy risks due to e-government initiative.

In stage 4, disclosed personal data were gathered, organized, and analyzed both for e-government and transparency. This analysis allowed us to determine existing privacy risks and their possible impact on Ecuadorian society, as well as to suggest strategies for mitigating them.

4. Results and Analysis

This section outlines the privacy risks related to e-government and transparency initiatives in Ecuador, examining the number of disclosed personal data by public institution.

4.1. E-Government and Its Related Privacy Risks

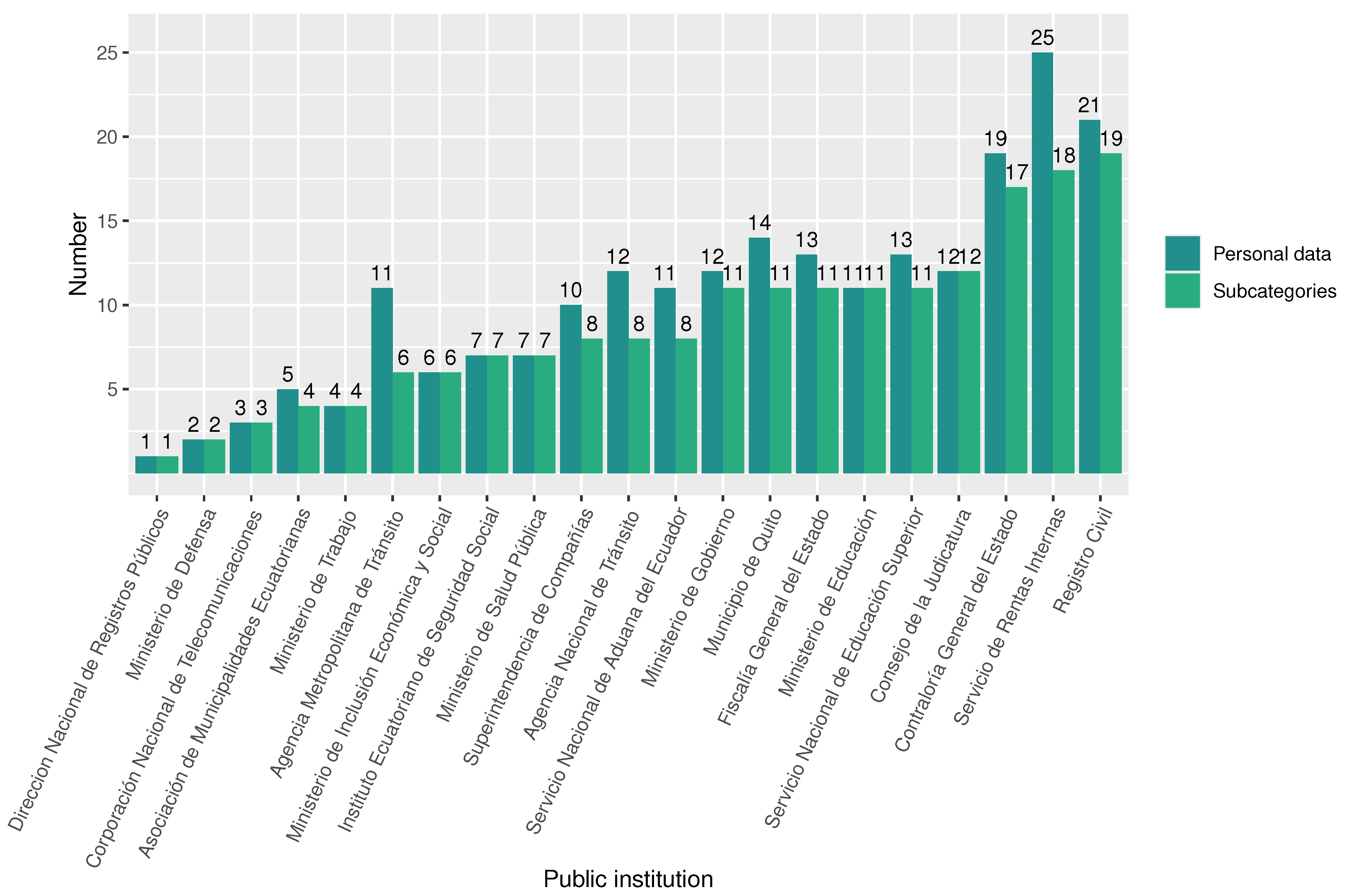

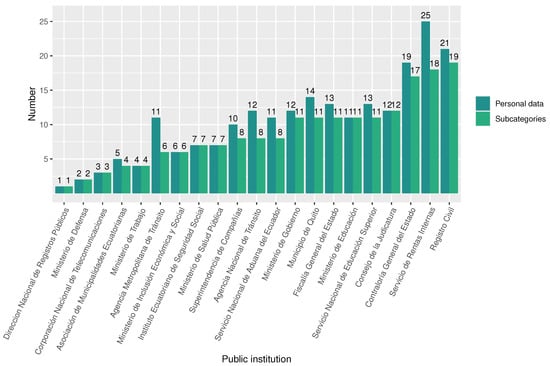

When analyzing the number of disclosed personal data and their corresponding subcategories by each public institution, we found that the entities that reveal the most personal data through open-access systems are Registro Civil (21 personal data in 19 subcategories), Servicio de Rentas Internas (SRI) (25 personal data in 25 subcategories), Contraloría General del Estado (19 personal data in 17 subcategories), and Consejo de la Judicatura (12 personal data in 12 subcategories), as shown in Figure 5. Specifically, Registro Civil and SRI host massive amounts of personal data belonging to all citizens, whereas Contraloría General del Estado and Consejo de la Judicatura concentrate personal data of citizens related to a specific context (in this case, public employees and citizens involved in judicial processes).

Figure 5.

Number of disclosed personal data and subcategories by public institution.

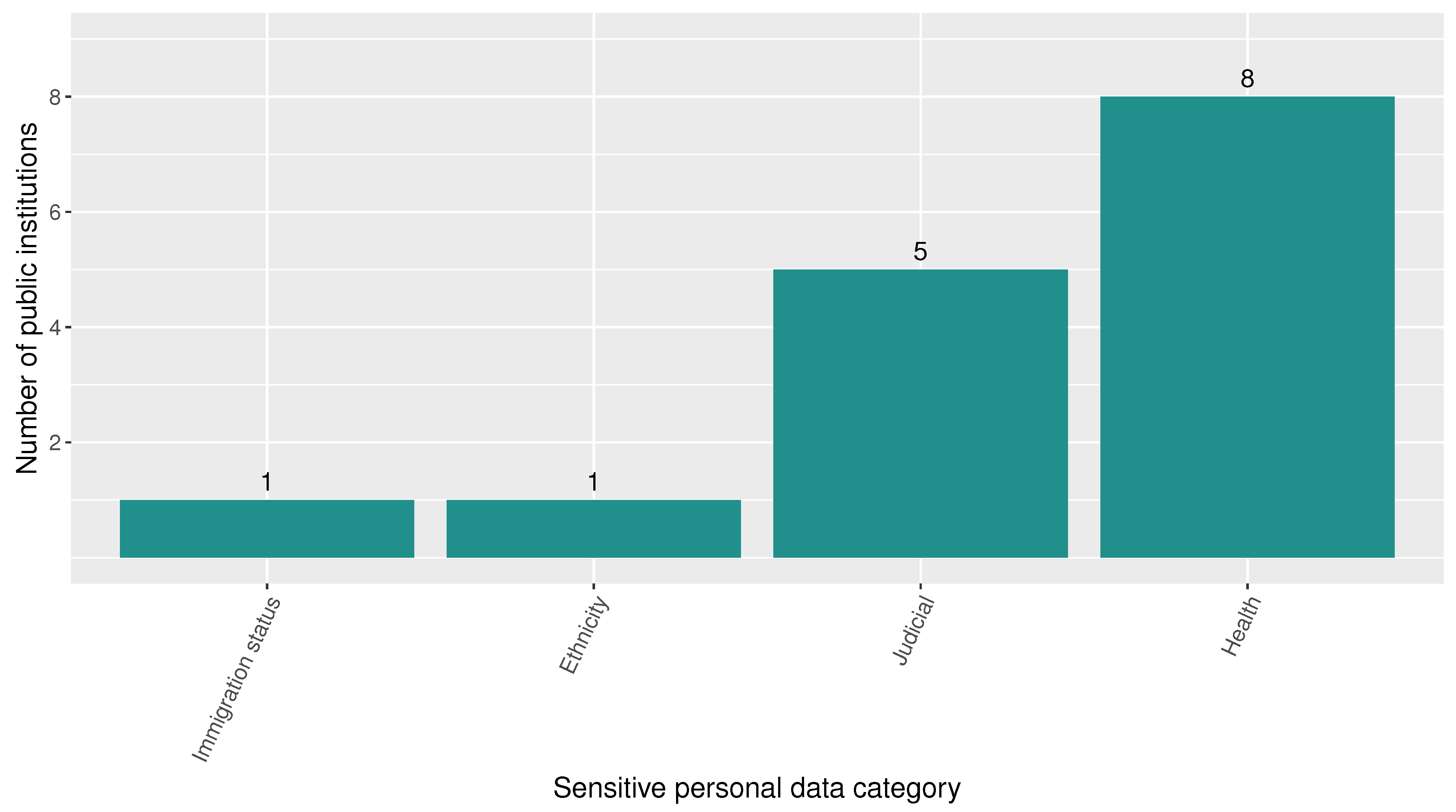

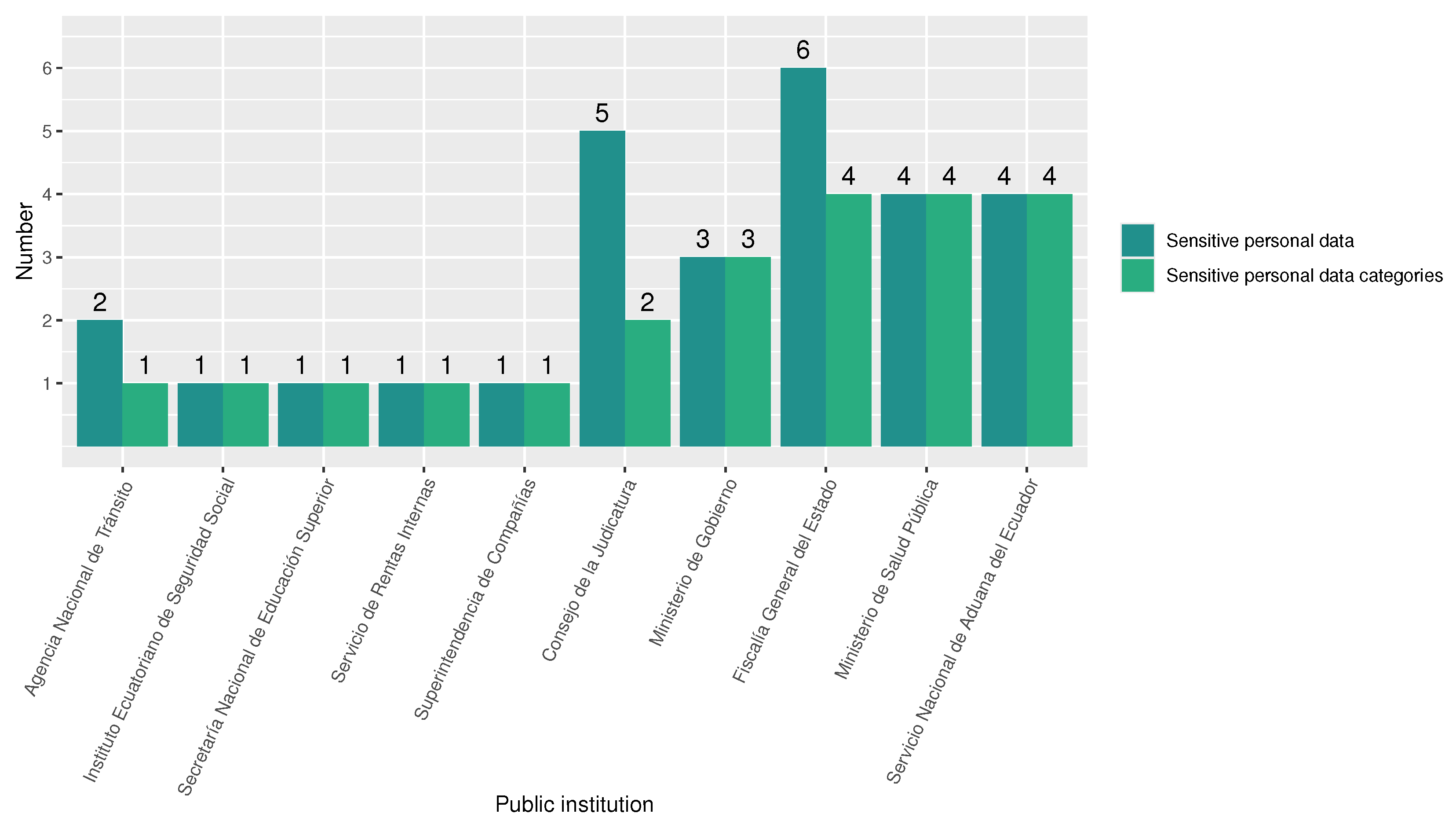

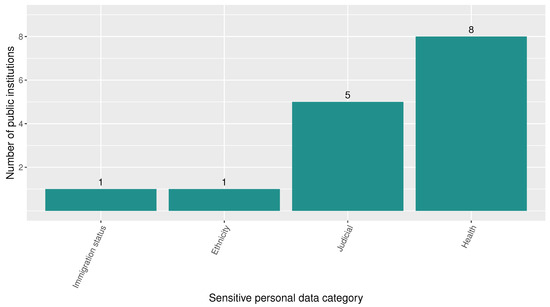

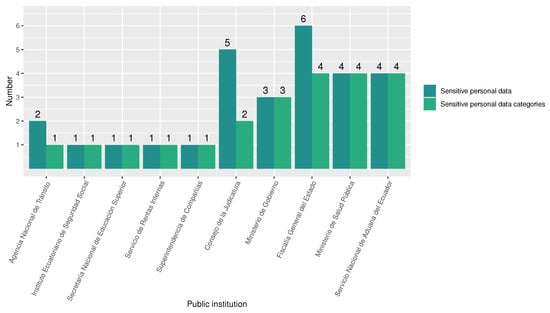

Regarding sensitive data (according to the LOPDP criteria), the statistical analysis demonstrates that roughly 72% of the 21 public institutions disclose at least one instance of sensitive personal data in one of the sensitive categories—Immigration status, Ethnicity, Judicial, and Health. While approximately 38% of public institutions reveal Health data, around 24% reveal Judicial history data. These statistics are exposed in Figure 6. In this sense, data on legal proceedings and infractions, health insurance status, and even details of a mother’s delivery process (such as the number of pregnancies and prenatal check-ups, among others) are exposed. The entities that disclose most of these personal data are detailed in Figure 7. Among all the revealed personal data by public institutions, 28% correspond to sensitive personal data.

Figure 6.

Number of public institutions that disclose sensitive personal data by sensitive personal data category according to LOPDP criteria.

Figure 7.

Number of disclosed sensitive personal data and sensitive personal data categories, according to LOPDP criteria, by public institution.

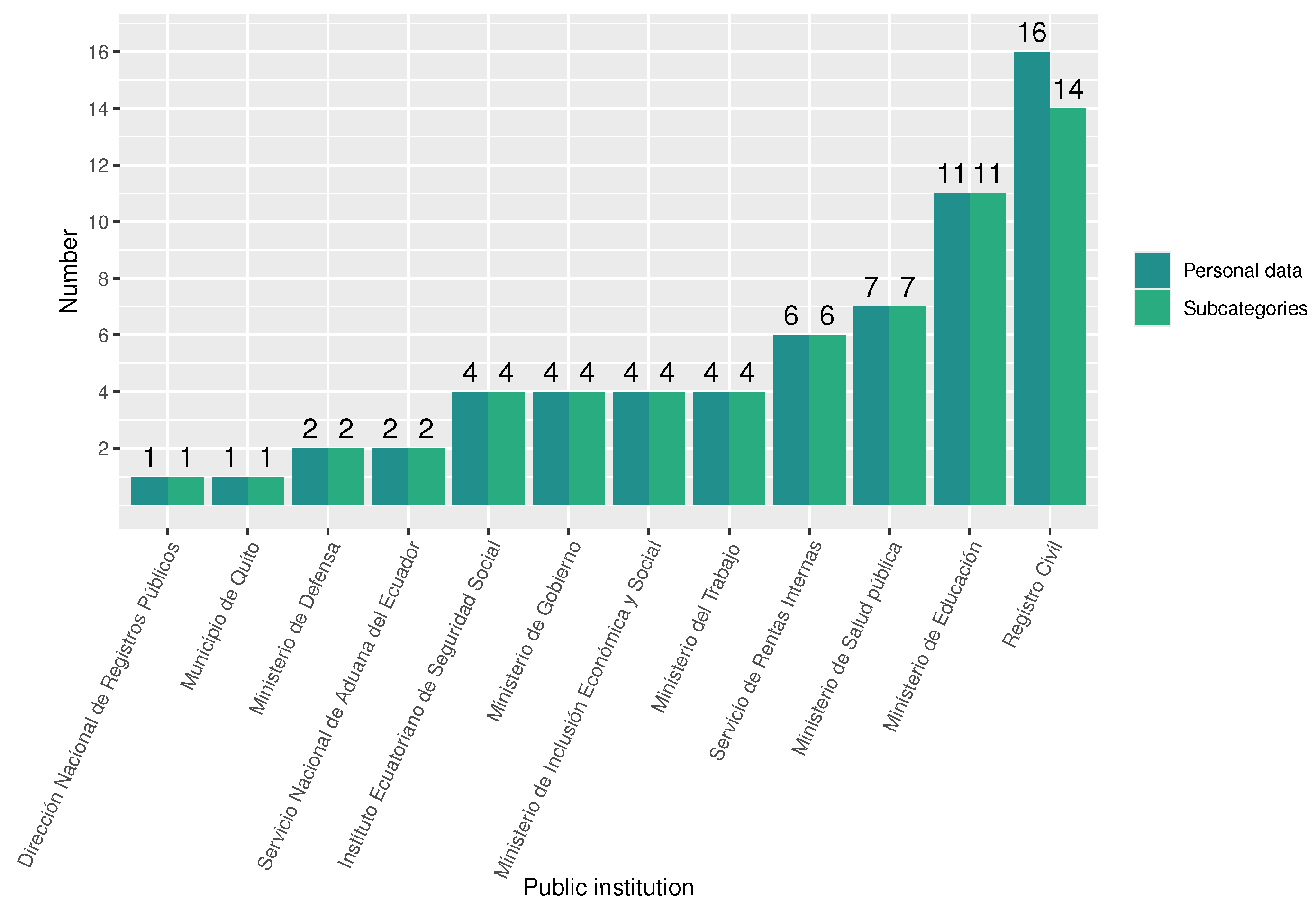

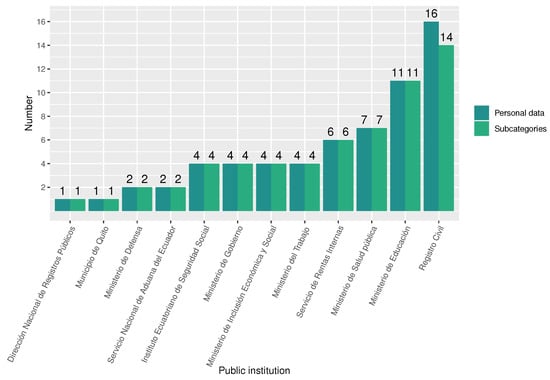

From the analysis of children and teenagers’ personal data, we found that Registro Civil (sixteen personal data in fourteen subcategories), Ministerio de Educación (eleven personal data in eleven subcategories), and Ministerio de Salud Pública (seven personal data in seven subcategories) are the institutions that disclose more personal data of these groups, as Figure 8 shows. The analysis demonstrates that 57% of the institutions reviewed disclose at least one personal data instance of children and teenagers—that is, more than half of the public institutions reveal the personal data of minors.

Figure 8.

Number of disclosed personal data and subcategories of children and teenagers by public institution.

Regarding the personal data of disabled people, a couple of systems were found that disclosed this type of data, but they stopped doing so during the completion of this research. These systems made it feasible to check if a citizen had received economic compensation or whether they had been subject to tax exemptions. The information that these systems revealed included compensation status, full names, type of physical disability, percentage of disability, and disability waiver amount.

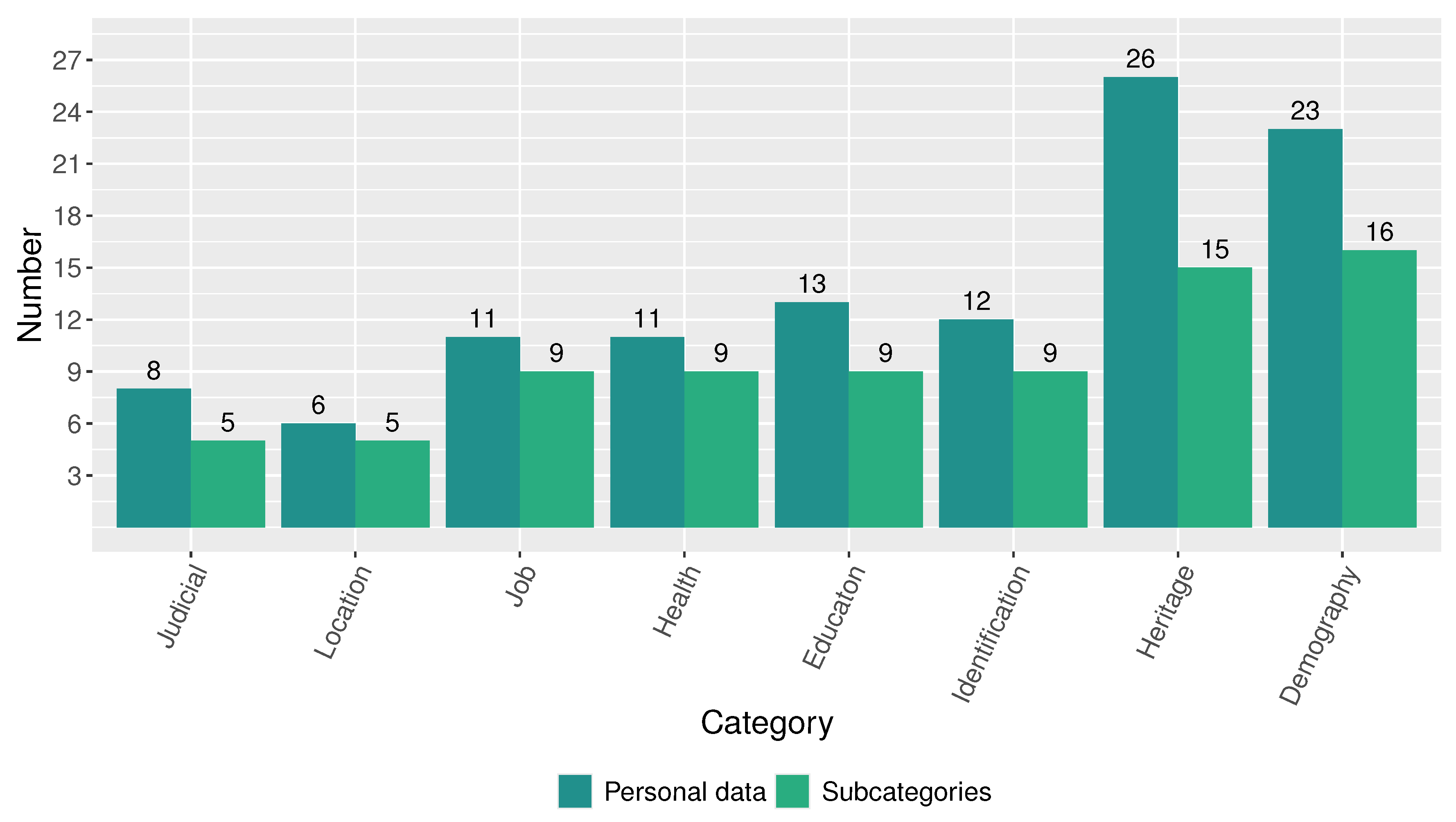

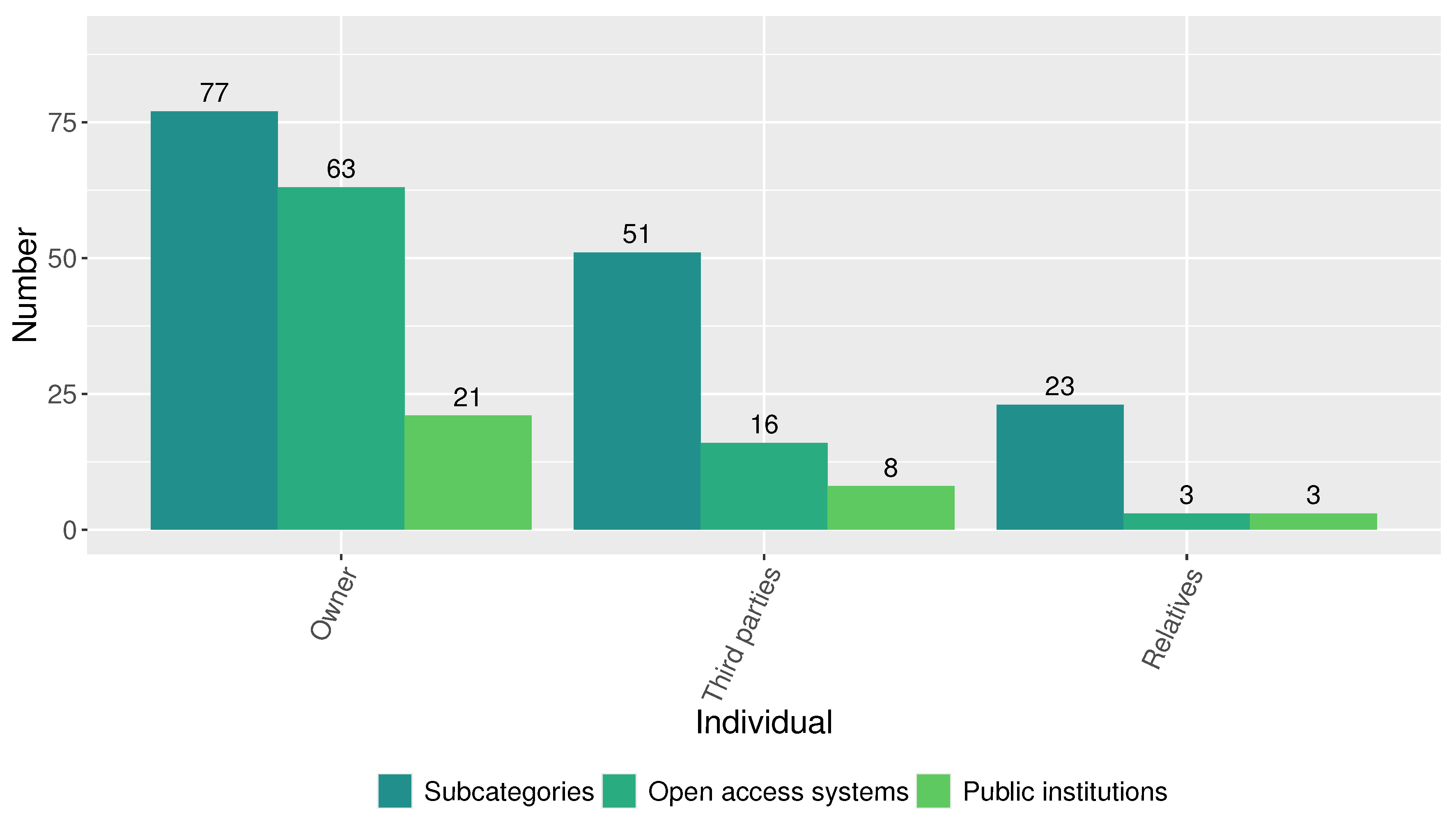

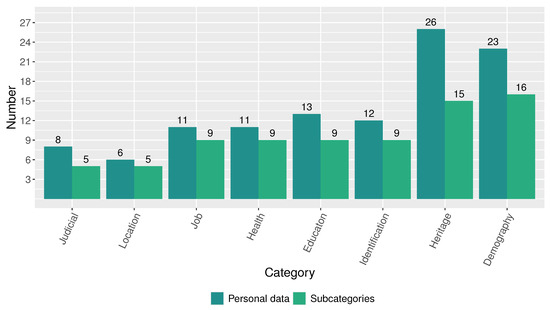

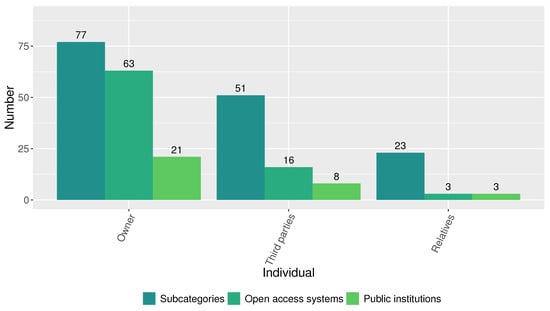

When analyzing the magnitude of the disclosed personal data by category, we found that those corresponding to the categories Demography (23 disclosed personal data in 16 subcategories) and Heritage (26 disclosed personal data in 15 subcategories) are the most critical, as shown in Figure 9. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 10, the open-access systems of the analyzed public institutions not only disclosed personal data of the individual but also about third parties and relatives. The results suggest a concerning scenario. All 21 public institutions collectively host 63 systems that expose 77 subcategories of individuals’ personal data. Additionally, sixteen systems across eight public institutions disclose personal data of 51 subcategories able to identify third parties, and three systems from three public institutions expose 23 subcategories of personal data capable of identifying relatives.

Figure 9.

Number of disclosed personal data and subcategories by category.

Figure 10.

Disclosed personal data by type of individual.

Regarding disclosed personal data by open-access systems, public institutions that reveal the greater number of personal data categories were Ministerio de Gobierno (disclosing personal data for about 62% of the categories), Fiscalía General del Estado (54%), Ministerio de Educación (54%), Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social (MIES) (54%), Registro Civil (54%), and Servicio de Rentas Internas (SRI) (54%). In addition, all the entities shared Identification data and more than 50% of the entities disclosed sensitive data of citizens. Other categories of personal data that are shared by more than half of the entities are Demography (62%) and Location (57%).

Beyond the large number of disclosed personal data by these systems, 25% of them were vulnerable to enumeration attacks—that is, with one or a few queries, results could be obtained about several individuals. For example, searching for a single last name returned results for all those who shared that last name. Furthermore, although the information in public consultation systems was usually sensitive and abundant, few protection mechanisms had been implemented.

Only 6% of the open-access systems analyzed implemented trivial privacy protection mechanisms. One common strategy identified was the generalization of certain data, such as the identification number or vehicle’s engine number, replacing the most specific part of such data with a symbol. Another common strategy was to add a watermark with the IP address of the user to the document that contains personal data to deter the leak of this information.

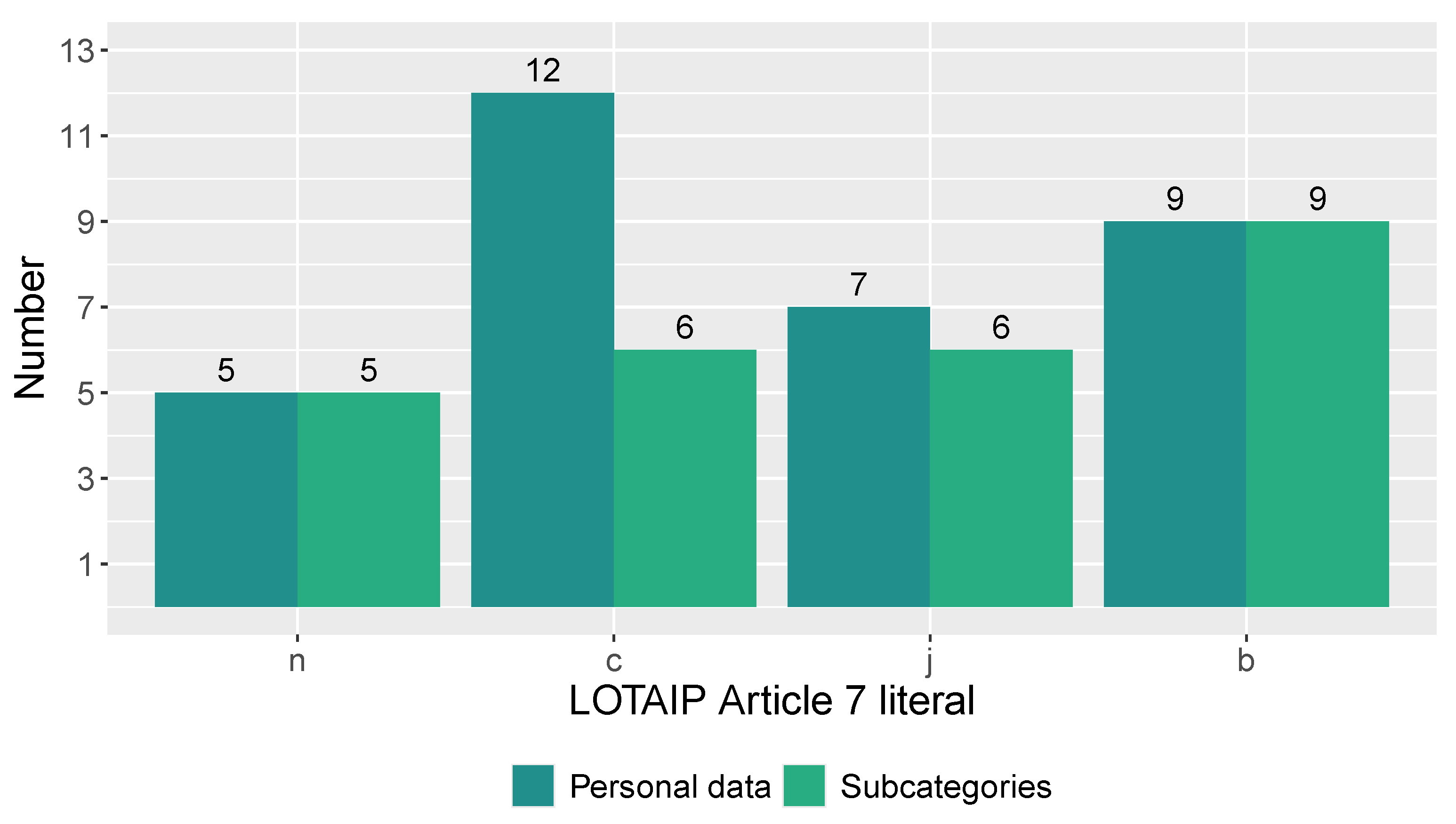

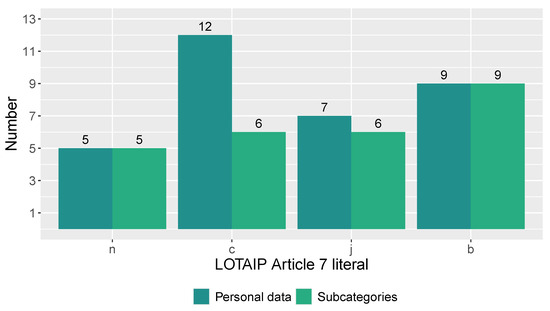

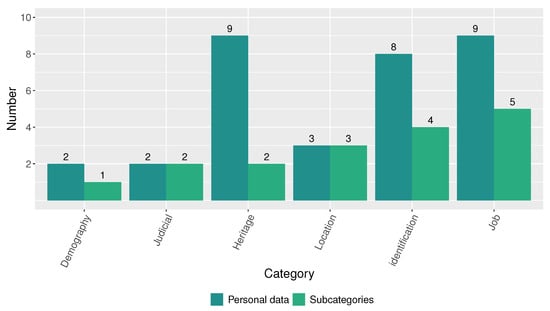

4.2. LOTAIP Analysis

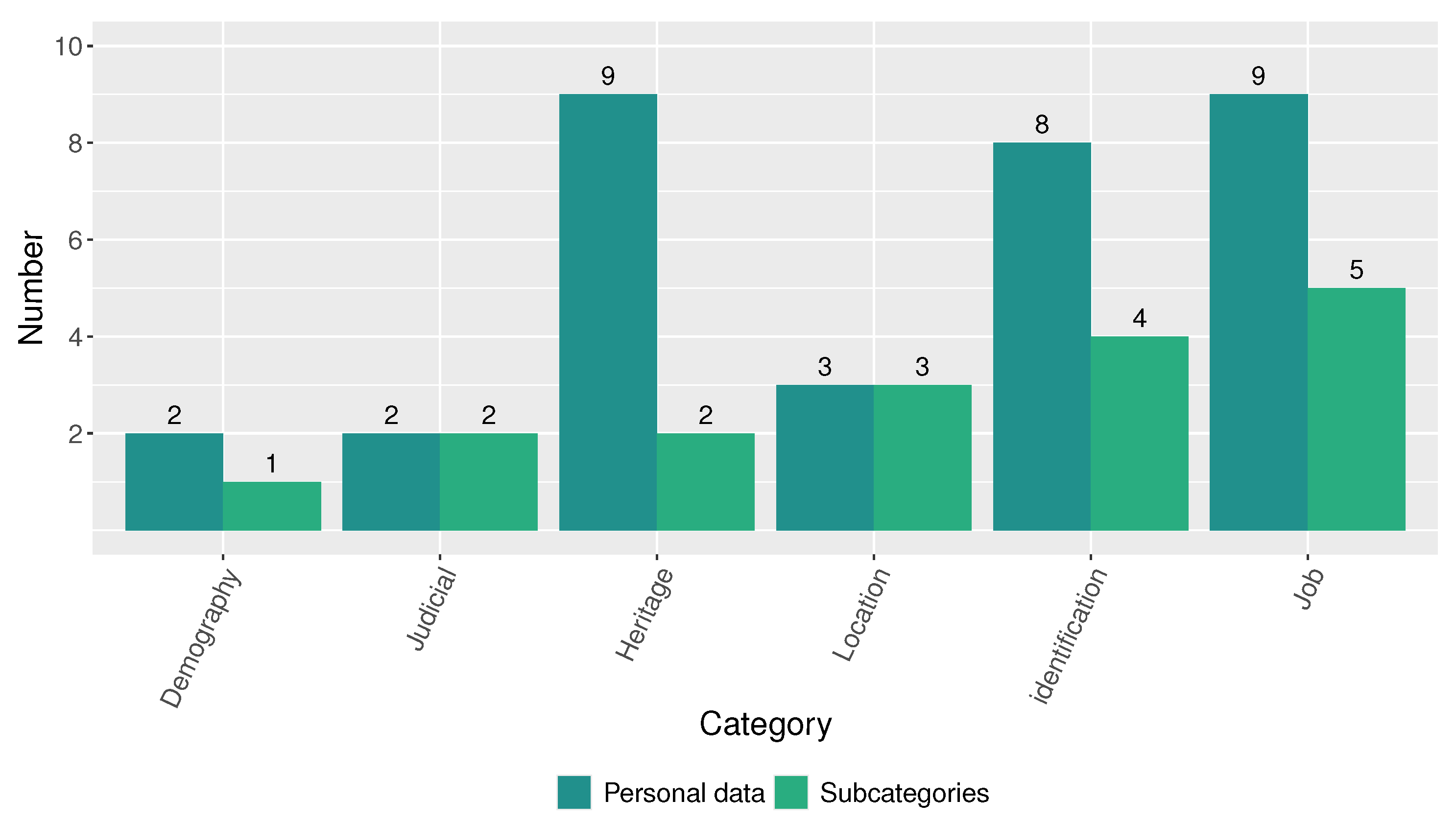

Figure 11 shows the number of personal data and subcategories that are disclosed by LOTAIP Article 7 literals described in Table 2 through the transparency section on online portals and websites of public institutions. Literal b (Institution Directory and Personnel Distributive) is the one that allows access to the greatest number of personal data. As Table 4 suggests, the LOTAIP initiative requires the publication of 17 subcategories of personal data, including full names, public sector position, income, contract details, and place of employment, among others. After categorizing these disclosed personal data, it is found that most correspond to the Job category (nine personal data in five subcategories) and the Identification category (eight personal data in four subcategories), although the Location and Heritage categories are also included, as denoted in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Number of personal data disclosed as a result of the application of Article 7 of the LOTAIP.

Figure 12.

Number of disclosed personal data and subcategories by category.

5. Discussion

Privacy risks and possible attacks: The results obtained show that e-government and transparency regulations affect privacy in Ecuador. First and foremost, identifying data are disclosed in almost all cases, allowing to correlate an identification number with the full name of an individual and vice versa. Also, an identification attack that uniquely identifies an individual within a population grouping of attributes that characterize him (quasi-identifiers) is feasible from the disclosed personal data of the 21 open-access systems.

Regarding transparency initiatives, both identifiers and full names are published together. Thus, an attacker who knows some of these data could easily obtain all the others that are disclosed. On the other hand, disclosed data associated with an identity could allow to classify or categorize an individual. For instance, wealth data (taxes, income, properties, among others) could place an individual in a category that prevents him from receiving credit or, what is even more worrying, in a category that attracts criminals interested in extorting, kidnapping, or stealing victims that stand out for their income level. Likewise, health or legal data could be input for institutions that discriminate against individuals based on the number of children or due to inconclusive legal proceedings.

The large amount of disclosed personal data can be consolidated to build a comprehensive profile that provides a clear view of an individual’s characteristics across various facets of their life. Just as a criminal investigator constructs a profile to study and ultimately apprehend a suspect, an attacker could use profiling to violate a victim’s privacy.

The risk to privacy in the analysis scenario of this research is exacerbated due to several factors. Firstly, who is in charge of disclosing the information is the Ecuadorian State, which certainly has the greatest amount of information of all citizens. Secondly, personal data are published directly on the Internet, significantly increasing the number of potential attackers. Thirdly, some open-access systems do not control the number of records that were obtained from queries; sometimes, many records are returned from a generic search parameter (for instance, searching for a last name returns information for everyone with that last name). In several cases, there are no minimum protection mechanisms that control the automated extraction of data, so there is a high risk that an attacker can easily obtain that information.

These factors that increase privacy risks for citizens also exacerbate the impact of the attacks described above. In fact, a virtual online mass surveillance platform has been created, due to the magnitude and granularity of the data disclosed, the number of individuals involved, the straightforward access to these data, and especially the sensitivity of these data, which include location, assets, and health, among others, and in many cases are constantly updated.

Vulnerable groups: As a result, all citizens (more than 18 million Ecuadorians [50]) are highly vulnerable to privacy attacks, even those groups that do not regularly interact with public services such as children (more than 6 million girls, boys, and teenagers [51]) or extremely vulnerable groups such as people with disabilities (more than 470,000) [52]). In particular, roughly 400,000 public employees are at risk [53], including more than 50,000 police officers and more than 40,000 employees among military forces, justice operators, mid-range authorities, and others [54], whose decision-making power in certain sensitive areas could put them at greater risk if their personal data are disclosed. This group, according to the exceptions established by the regulation, would have their privacy rights restricted. In contrast, activities related to freedom of expression (generally journalistic), which could be carried out by any citizen, would not be required to consider these privacy rights, which could generate serious distortions in the protection of personal data.

Given that e-government and transparency are considered as solutions for serious problems in Ecuadorian society (corruption, online services, among others) and given the citizenship acceptance that their implementation has had in Ecuador, their adoption will surely continue to grow in the coming years with the consequent aggravation of the effects on citizens privacy. Thus, more public institutions that handle huge amounts of personal data will be integrated, including municipal governments and smaller institutions. Finally, this research allows us to state that third parties are already using personal data. For example, there are several Internet sites and mobile applications that concentrate access to the open-access systems, generating revenue through online advertising.

In addition, although these systems have been used by journalists to uncover cases of corruption in public purchases or in the issuance of fraudulent documents, there are cases in which they are used to extract data from a media target in order to attack it. Therefore, criminals take advantage of these data to carry out, for instance, harassment and extortion against their victims.

Protection mechanisms: In order to mitigate these privacy risks, several protection mechanisms could be implemented. First of all, the use of a CAPTCHA control that helps to prevent automated extraction of personal data must be implemented. Only half of the analyzed open-access systems implement a CAPTCHA control, while only four adopt useless privacy protection mechanisms. The adoption of access control mechanisms could also be considered, which allow access to the data only to its owner or to a more restricted group of users who legitimately require the use of said data. Part of this strategy could be to record the access to the data and particularly of the individual accessing it (for example, registering the source IP address and identification data, among others) so that usage patterns can be determined to help to detect, for instance, malicious use of these data.

Another strategy to mitigate the impact on the privacy of citizens consists in minimizing data—that is, disclosing what is just strictly necessary. For this, it would be necessary to reduce as much as possible the amount of personal data that is disclosed, since the results of this research lead us to determine that there are too many disclosed personal data with excessive granularity. Also, it is important to analyze the exceptions of the legal Ecuadorian framework to the guarantee of privacy rights, as well as to observe the application of this legal framework in terms of transparency and e-government.

Finally, it is the citizens themselves who must be aware of the risks they face when indiscriminately providing and revealing their personal data, often sharing far more information than is actually required for a given process. Therefore, it is urgently necessary to create awareness campaigns that promote a culture of privacy in Ecuador. Table 6 summarizes and details some protection mechanisms to prevent personal data leaks in the Ecuadorian context.

Table 6.

Proposed protection mechanisms to prevent personal data leaks in the Ecuadorian context.

6. Conclusions

While enhancing administrative efficiency and free access to public information, e-government and transparency initiatives pose significant privacy risks in Ecuador. The massive publication of personal data, including names, income, health status, and judicial data, exposes citizens to serious risks such as identity theft, extortion, and discrimination.

Moreover, the recent enactment of privacy regulations in Ecuador highlights important gaps in their implementation. For instance, the disclosure of public employees’ data, combined with the absence of robust control mechanisms for access systems, further exacerbates these risks. Concerningly, the disclosed data often include information about vulnerable groups, such as children and individuals with disabilities, which amplifies their risk of harm. Thus, implementing stricter restrictions is crucial to safeguard their privacy.

Public access systems lack essential security features, including limitations on the amount of data retrievable in a single query. This deficiency facilitates enumeration attacks and enables large-scale access to sensitive information, further compromising data protection. Current practices in data publication often prioritize transparency at the expense of privacy. To address this, a shift towards data minimization is necessary, ensuring that only the information strictly required to meet transparency objectives is disclosed. This approach not only reduces the risk of data misuse but also aligns better with modern principles of privacy by design, which advocate embedding privacy protections directly into data practices.

The findings underscore global challenges, particularly in developing countries where regulatory frameworks and privacy cultures may be underdeveloped. By contrast, a design-oriented approach to privacy emphasizes proactive measures to prevent misuse from the outset, offering a model that could guide these nations in crafting more robust privacy protections. While current strategies focus on reactive measures like strengthening access controls and monitoring usage patterns, a privacy-by-design framework emphasizes preventive actions. For instance, integrating secure data practices from the inception of policies and systems could significantly mitigate risks. Additionally, public education on data safety remains a critical component for ensuring a privacy-conscious society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.-C. and A.R.-H.; methodology, C.P.-C., D.C.-S. and A.R.-H.; software, D.C.-S.; validation, C.P.-C., D.C.-S. and A.R.-H.; formal analysis, C.P.-C. and J.E.-J.; investigation, C.P.-C. and D.C.-S.; resources, A.R.-H. and J.E.-J.; data curation, C.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.-S. and J.E.-J.; writing—review and editing, D.C.-S. and J.E.-J.; visualization, C.P.-C., D.C.-S. and A.R.-H.; supervision, J.E.-J.; project administration, A.R.-H. and J.E.-J.; funding acquisition, J.E.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of the results of this research is funded by the Escuela Politécnica Nacional, in particular through the project “Híper-transparencia Digital en Ecuador: El Gobierno Electrónico contra la Privacidad”, ref. PII-DETRI-2022-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the files required for reproducibility of experiments are publicly available at https://github.com/dcevallossalas/privacybreaches (accessed on 5 March 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, C. China’s privacy protection strategy and its geopolitical implications. Asian Rev. Political Econ. 2024, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wairimu, S.; Iwaya, L.H.; Fritsch, L.; Lindskog, S. On the Evaluation of Privacy Impact Assessment and Privacy Risk Assessment Methodologies: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 19625–19650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Hooda, A.; Jeyaraj, A.; Seddon, J.; Dwivedi, Y. Trust, Risk, Privacy and Security in e-Government Use: Insights from a MASEM Analysis. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abomhara, M.; Nweke, L.O.; Yayilgan, S.Y.; Comparin, D.; Teyras, K.; de Labriolle, S. Enhancing privacy protections in national identification systems: An examination of stakeholders’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices of privacy by design. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2024, 23, 3665–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Königs, P. Government Surveillance, Privacy, and Legitimacy. Philos. Technol. 2022, 35, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Argudo, M.; Matute-Pinos, K.; Fernández-Mora, M. Comparative analysis of the Organic Law on Personal Data Protection of Ecuador with Colombian legislation from a cybersecurity and cybercrime approach; [Análisis comparativo de la Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales del Ecuador con la legislación colombiana desde un enfoque de ciberseguridad y delitos informáticos]. Rev. Iber. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2023, 2023, 100–114. [Google Scholar]

- Califano, B. Privacy and data protection in Latin America: Regulatory initiatives and collisions with the right to freedom of expression on the internet. J. Digit. Media Policy 2023, 14, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arturo, L.G. Practicality, support or premeditated calculation in the digital age: The case of ecuador; [Practicidad, ayuda o cálculo premeditado en la era digital: El caso de ecuador]. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2021, 26, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero Olarte, S.; Torrent, J.; Aguirre, K. Internet use at work and income inequality in Ecuador. Technol. Soc. 2024, 79, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villao, D.; Vera, G.; Duque, V.; Mazón, L. Opportunities and Challenges of Digital Transformation in the Public Sector: The Case of Ecuador. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atobishi, T.; Mansur, H. Bridging Digital Divides: Validating Government ICT Investments Accelerating Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Hasan, N.A.M.; Zamri bin Ahmad, A.M. Exploring Satisfaction and Trust as Key Drivers of e-Government Continuance Intention: Evidence from China for Sustainable Digital Governance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurjonsson, T.O.; Jónsson, E.; Gudmundsdottir, S. Sustainability of Digital Initiatives in Public Services in Digital Transformation of Local Government: Insights and Implications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghareeb, M.; Albesher, A.S.; Asif, A. Studying Users’ Perceptions of COVID-19 Mobile Applications in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloshchapova, T.; Yamashev, V.; Skornichenko, N.; Strielkowski, W. E-Government as a Key to the Economic Prosperity and Sustainable Development in the Post-COVID Era. Economies 2023, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrègue, B.F.G.; Bogoni, A. Privacy and Security Concerns in the Smart City. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 586–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeebaree, M.; Agoyi, M.; Aqel, M. Sustainable Adoption of E-Government from the UTAUT Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Protecting personal data in E-government: A cross-country study. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintin, R.A.; Chavez, C.C.; Altamirano, J.P.; Tintin, L.M. Could E-government Development Contribute to Reduce Corruption Globally? In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on eDemocracy and eGovernment, ICEDEG, Ambato, Ecuador, 4–6 April 2018; pp. 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Navarro, J.J.; Munive, J.A.; Alonso Montes, J.I.; Ibujés Villacís, J.M.; Casas Jiménez, C.M.; Urquíza Suarez, J.C. On the role of R&D in e-government in Ecuador: Strategic plan in ICT for Ecuador in the field of information society and e-government. In Proceedings of the 2014 1st International Conference on eDemocracy and eGovernment, ICEDEG, Quito, Ecuador, 24–25 April 2014; 25 April 2014; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información. Desarrollo de Gobierno Electrónico en la Administración Pública de Ecuador. Available online: https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Desarrollo-de-Gobierno-Electr%C3%B3nico-en-la-Administraci%C3%B3n-P%C3%BAblica-de-Ecuador-1.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Triviño, R.D. State of open government data as a process in Ecuador. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on eDemocracy and eGovernment, ICEDEG, Sangolqui, Ecuador, 30 March–1 April 2016; pp. 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría Nacional de la Administración Pública 2014. Plan Nacional de Gobierno Electrónico. Available online: https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Plan-Gobierno-Electronico-2014-2017.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Secretaría Nacional de la Administración Pública 2016. Plan Nacional de Gobierno Electrónico. Available online: https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2017/02/Plan-Gobierno-Electro%CC%81nico-2017.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Gobierno de la República del Ecuador. Declara Politica de Estado, la Mejora y simplificacion de Tramites. Decreto Ejecutivo 372, Publicado en Registro Oficial Suplemento 234 de 4 de Mayo de 2018. Available online: https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Decreto-Ejecutivo-372.pdf. (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Ministerio de Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información. Plan Nacional de Gobierno Electrónico 2018–2021. Available online: https://www.gobiernoelectronico.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/PNGE_2018_2021sv2.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Gob.ec. Gob.ec Portal Único de Trámites Ciudadanos. Available online: https://www.gob.ec/ (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Secretaría Nacional de la Administración Pública 2016. United Nations E-Government Knowledgebase. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Data/Country-Information/id/52-Ecuador (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Morales, V.; Robalino-Lopez, A. Framework for the Evaluation of Internet Development. Case Study: Application of Internet Universality Indicators in Ecuador. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on eDemocracy and eGovernment, ICEDEG, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–24 April 2020; pp. 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 24 Registro Oficial Suplemento 337 de 18-May.-2004. Ley Orgánica de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública. Available online: https://www.oas.org/juridico/PDFs/mesicic5_ecu_ane_cpccs_22_ley_org_tran_acc_inf_pub.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Troya, M.S.; El País, D. La Ley de Transparencia No es la Panacea de Lucha Contra la Corrupción. Available online: https://elpais.com/politica/2013/05/14/actualidad/1368526514_140115.html (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Global Right to Information Rating. Mapa de Calificación Global del Derecho a la Información. Available online: https://www.rti-rating.org/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Asamblea Nacional. Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales. Available online: https://www.telecomunicaciones.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Ley-Organica-de-Datos-Personales.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador. Ley de Comercio Electrónico, Firmas y Mensajes de Datos. Available online: https://www.telecomunicaciones.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/11/Ley-de-Comercio-Electronico-Firmas-y-Mensajes-de-Datos.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- COSEDE 2023. Reglamento de la Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales. Available online: https://www.cosede.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/REGLAMENTO-GENERAL-A-LA-LEY-ORG%C3%81NICA-DE-PROTECCION-DE-DATOS-PERSONALES_compressed-1.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Cevallos-Salas, D.; Estrada-Jiménez, J.; Guamán, D.S. Application layer security for Internet communications: A comprehensive review, challenges, and future trends. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 119, 109498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primicias. AMT Recomienda Revisar Datos en la ANT y el SRI Tras Sufrir Hackeo en Claves del Sistema de Matriculación. Available online: https://www.primicias.ec/quito/hackeo-claves-amt-matriculacion-vehicular-tramites-irregulares-80776/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Diario El Comercio. Registro Civil Denuncia Presunto Ciberataque en su Agencia Virtual. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/seguridad/registro-civil-denuncia-presunto-ciberataque-agencia-virtual.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Cevallos-Salas, D.; Grijalva, F.; Estrada-Jiménez, J.; Benítez, D.; Andrade, R. Obfuscated Privacy Malware Classifiers Based on Memory Dumping Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 17481–17498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario El Comercio. Fiscalía Investiga Ataque Cibernético a Sistema Informático de la ANT. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/seguridad/fiscalia-investigacion-ataque-cibernetico-ant.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Diario El Comercio. Virus RansomEXX es el Responsable del Ciberataque a CNT. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/negocios/virus-ransomeware-cnt-ministerio-telecomunicaciones.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Diario El Comercio. Municipio de Quito Suspende Trámites Digitales por Ataque de Hackers. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/municipio-quito-ataque-hacker-tramites.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Minsterio de Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información. Gobierno Enviará a la Asamblea Nacional, Ley de Protección de Datos Personales. Available online: https://www.telecomunicaciones.gob.ec/gobierno-enviara-a-la-asamblea-nacional-ley-de-proteccion-de-datos-personales (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- BBC News Mundo. Filtración de Datos en Ecuador: La “Grave Falla Informática” Que Expuso la Información Personal de Casi Toda la Población del País Sudamericano. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-49721456 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Diario El Comercio. Policía da Detalles Sobre Acceso no Consentido a Su Sistema. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/seguridad/policia-sistema-hackeo-naomi-arcentales.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Primicias. AMT Denuncia Hackeo de 35 Usuarios del Sistema de Matriculación Vehicular. Available online: https://www.primicias.ec/quito/amt-denuncia-hackeo-usuarios-matriculacion-vehicular-80714/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Ecuador Legal Online. EcuadorLegalOnline. Available online: http://www.ecuadorlegalonline.com (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Ecuador WEB. Ecuador WEB. Available online: https://ecuadorweb.net (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Elvis Fernando. Consultas Ecuador. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=ec.consultasecuador.app&hl=es_EC&gl=US (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Expansión DatosMacro. Ecuador: Economía y Demografía. Available online: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/paises/ecuador (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ministerio de Inclusión Económica y Social. Plan de Protección Integral de la niñEz y Adolescencia Al 2030. Available online: https://www.igualdad.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2021/05/plan2030_ninez_version_consulta_compressed.pdf. (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Consejo Nacional Para la Igualdad de Discapacidades. Estadísticas de Discapacidad. Available online: https://www.consejodiscapacidades.gob.ec/estadisticas-de-discapacidad/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Primicias. En Cuatro Años el Gobierno Central Redujo Más de 33.000 Funcionarios. Available online: https://www.primicias.ec/noticias/economia/gobierno-desvinculacion-funcionarios-ahorro-ecuador (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ministerio de Defensa del Ecuador. Fuerzas Armadas del Ecuador. Available online: https://www.defensa.gob.ec/fuerzas-armadas-ecuador (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Lu, D.; Han, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Ma, X.; Li, T.; Ma, J. A secured TPM integration scheme towards smart embedded system based collaboration network. Comput. Secur. 2020, 97, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, G.; Jang, J.; Choi, S.; Shin, D. Research on Improving Cyber Resilience by Integrating the Zero Trust Security Model With the MITRE ATT & CK Matrix. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 89291–89309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhazi, B.; Alshaikh, M.; Alkhezi, S.; Labbaci, H. Assessment of the Impact of Information Security Awareness Training Methods on Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 132132–132143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, A.; Acitelli, G.; Marrella, A.; Bonomi, S.; Angelini, M. A compliance assessment system for Incident Management process. Comput. Secur. 2024, 146, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schyff, K.; Prior, S.; Renaud, K. Privacy policy analysis: A scoping review and research agenda. Comput. Secur. 2024, 146, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuletič, S.; Vrhovec, S.; Skela-Savič, B.; Žvanut, B. Security and privacy oriented information security culture (ISC): Explaining unauthorized access to healthcare data by nursing employees. Comput. Secur. 2024, 136, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).