Exploring the Boundaries of Success: A Literature Review and Research Agenda on Resource, Complementary, and Ecological Boundaries in Digital Platform Business Model Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

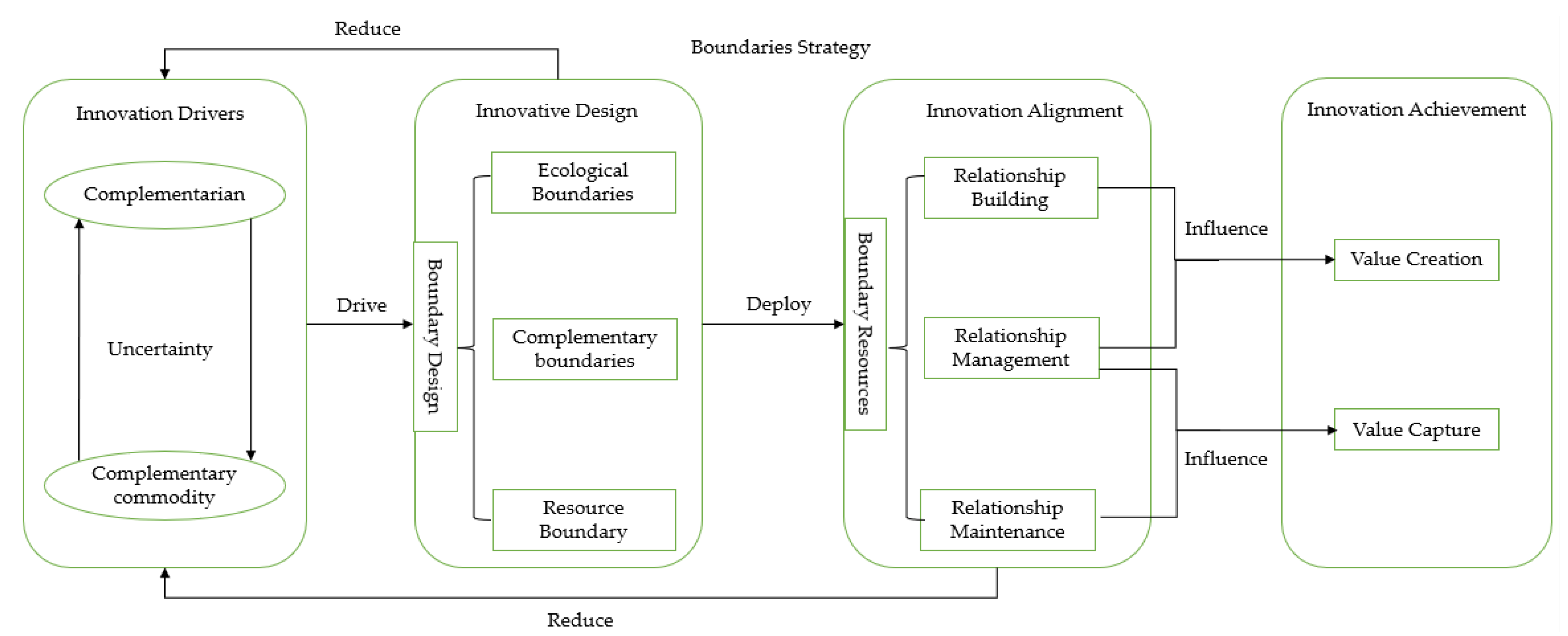

- First, it deconstructs the innovation process of digital platform business models from a boundary perspective and offers a new perspective of understanding the digital platform business models;

- Second, it explores the boundaries of success in digital platform business models, which are critical for practitioners and researchers to fully understand the complex interplay between resources, complementary assets, and the broader ecological context in which these platforms operate;

- Thirdly, it combines structural and relational elements of digital platforms to explain the process of value creation and acquisition, which can help digital platform owners understand the process of creating value and capture it more effectively;

- Fourthly, it provides an in-depth analysis of the importance of boundary design and boundary resource deployment in digital platform business model innovation, which can help digital platform owners to effectively manage complementor and complementary product uncertainty and promote value co-creation;

- Lastly, it provides guidance for digital platform owners to achieve business model innovation through boundary design and boundary resource deployment and achieve sustainable growth.

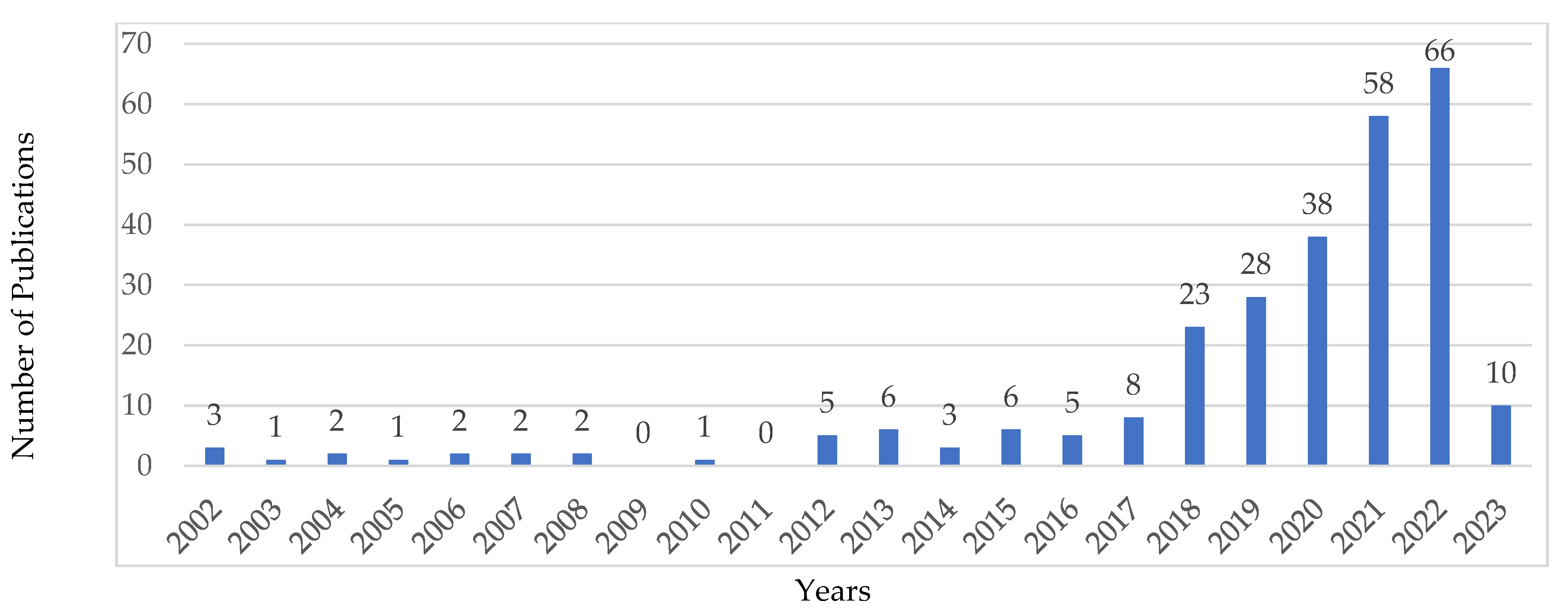

2. Research Methodology

- The main subject of the literature must be a digital platform, meaning the literature should focus on businesses or organizations that operate primarily online or through digital means;

- The perspective of the literature should be on business model innovation, meaning the literature should focus on the development and implementation of new and unique business models within the digital platform industry.

3. Digital Platform: Connotation and Extension

3.1. Definition of Digital Platform

- Connection: digital platforms connect external groups through boundary resources such as digital technologies, data, and algorithms.

- Interaction: digital platforms provide interaction mechanisms, such as matchmaking, feedback, and communication tools, to match supply and demand.

- Value co-creation: digital platforms enable the creation, transmission, and acquisition of value through the interactions and connections facilitated by the platform.

3.2. Composition and Innovation Elements of Digital Platforms

3.2.1. Digital Infrastructure

3.2.2. Modular Architecture

- Facilitating distributed innovation: Modular architecture allows platform owners to disperse large-scale innovation across many external complementors’ innovation activities, reducing the costs of digital platform innovation while spreading the risk of innovation across complementors.

- Facilitating incremental or disruptive innovation: Scholars have different and even opposing views on the effects of modularization on incremental and disruptive innovation. Klos et al. [43] argue that modular architecture is conducive to incremental innovation but can become an obstacle to disruptive innovation. However, Kohtamäki et al. [20] argue that modular architecture expands the boundaries of resources and organizations and can acquire heterogeneous complementors while enriching innovation factors, thus favoring disruptive innovation.

- Releasing complementors’ cognitive constraints: The concept of releasing complementors’ cognitive constraints is a crucial aspect of promoting innovation and creativity within digital platforms. By enabling complementors, who are external entities that create value for the platform, to focus on their unique strengths and capabilities, digital platforms can enhance their overall performance and competitiveness. One notable example of this is the deep-learning development platform TensorFlow, which utilizes a modularized approach to the underlying code. This approach enables researchers to avoid the tedious and time-consuming process of reinventing the wheel, allowing them to focus on their own innovative contributions. This approach not only reduces the cognitive constraints on complementors but also provides a platform for collaboration and knowledge sharing, leading to improved innovation capacity and a more robust digital ecosystem. Through the modularization of the underlying code, TensorFlow offers complementors the opportunity to leverage existing functionalities and build upon them to create innovative solutions. By doing so, complementors can focus on their areas of expertise and create novel applications that enhance the platform’s overall value proposition. This approach also encourages complementors to share their knowledge and insights, fostering a community of practice that drives innovation and supports the growth of the platform.

- Improving complementors’ independence and promoting the rate of complementary innovation [17]: In the context of digital platforms, improving complementors’ independence and promoting the rate of complementary innovation can be crucial factors for driving overall innovation and success. This approach involves enabling and empowering complementors, third-party developers, suppliers, and other actors who create and deliver complementary products or services on the platform, to innovate and create value more freely and effectively. One key way to improve complementors’ independence is by providing them with the tools, resources, and support they need to innovate on their own terms. This may include offering access to platform data, APIs, and other resources that can help complementors create new products and services that integrate more seamlessly with the platform. It may also involve providing training, mentoring, or other forms of support that can help complementors develop their skills and capabilities. Promoting the rate of complementary innovation can also be an important factor in driving overall platform success. This involves creating an ecosystem that fosters collaboration and competition among complementors, as well as providing incentives for them to innovate and differentiate themselves from one another. For example, a platform may offer rewards or recognition to the most innovative complementors, or it may host competitions or challenges that encourage complementors to develop new and innovative products or services.

3.3. Digital Platform Business Model

4. Innovation of Digital Platform Business Models

4.1. Innovative Design: Uncertainty and Boundary Design

4.1.1. Complementarian and Complementary Uncertainties

4.1.2. Platform Boundary Design

4.2. Innovative Alignment: Boundary Resources and Relational Governance

4.2.1. Boundary Resources and Relationship Creation

4.2.2. Boundary Resources and Relationship Management

4.2.3. Boundary Resources and Relationship Maintenance

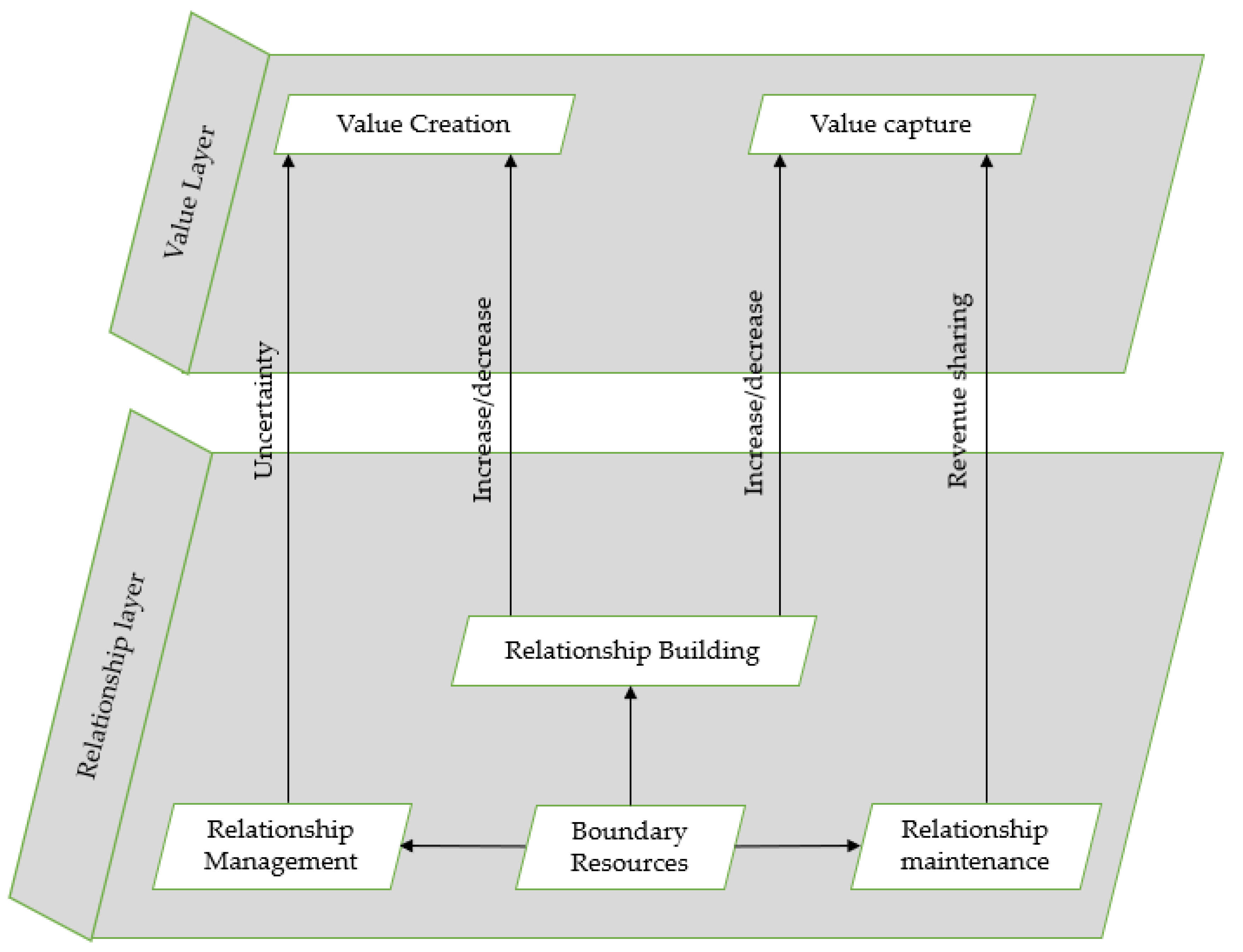

4.3. Innovation Realization: Relationship Governance and Value Analysis

4.3.1. Relationship Building and Value Creation

4.3.2. Relationship Management and Value Creation

4.3.3. Relationship Maintenance and Value Capture

5. Discussion and Future Agenda

5.1. Digital Infrastructure and Modular Architecture of Digital Platforms

5.2. Digital Platform Business Model Design

5.3. Boundary Resources and Value Co-Creation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulkader, B.; Magni, D.; Cillo, V.; Papa, A.; Micera, R. Aligning firm’s value system and open innovation: A new framework of business process management beyond the business model innovation. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020, 26, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciarini, C.; Borelli, F.; Capo, F.; Cappa, F.; Sarrocco, C. Can digitalization favour the emergence of innovative and sustainable business models? A qualitative exploration in the automotive sector. J. Strategy Manag. 2022, 15, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.; Aagaard, A.; Magnusson, M. Exploring business model innovation in SMEs in a digital context: Organizing search behaviours, experimentation and decision-making. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2022, 31, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R. The business model: Present and future—Beyond a skeumorph. Strateg. Organ. 2013, 11, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoo, S.; Cucculelli, M.; Qamar, D. Artificial intelligence and corporate innovation: A review and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 188, 122264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Reuver, M.; Sørensen, C.; Basole, R. The Digital Platform: A Research Agenda. J. Inf. Technol. 2018, 33, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, R.; Fiorentino, R.; Garzella, S.; Lombardi, R. The role of boundary management in open innovation: Towards a 3D perspective. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.; Grigoroudis, E.; Stamati, D.; Valvi, T. Social Business Model Innovation: A Quadruple/Quintuple Helix-Based Social Innovation Ecosystem. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, P.; Henfridsson, O.; Parker, G.G. Introduction—Platforms and Infrastructures in the Digital Age. Inf. Syst. Res. 2018, 29, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Converging and diverging business model innovation in regional intersectoral cooperation–Exploring wine industry 4.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 1625–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, V.; Simmons, G.; Truong, Y.; Palmer, M.; Schneckenberg, D. An exploration of business model development in the commercialization of technology innovations. RD Manag. 2014, 44, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltean, F.; van Bruggen, G. Digital Technologies, Marketing Agility, and Marketing Management Support Systems: How to Remain Competitive in Changing Markets. In Organizational Innovation in the Digital Age; Machado, C., Davim, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Ghauri, P.; Ogbonna, N.; Xing, X. Platform-based business model and entrepreneurs from Base of the Pyramid. Technovation 2023, 119, 102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. The platform business model and business ecosystem: Quality management and revenue structures. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 2113–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Min, J. Supplier, Tailor, and Facilitator: Typology of Platform Business Models. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, A.; Javed, A.; Kohda, Y. Exploring the Role of Boundary Spanning towards Service Ecosystem Expansion: A Case of Careem in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, A.; Schreieck, M.; Riasanow, T.; Setzke, D.; Wiesche, M.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Digital platform ecosystems. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Oghazi, P.; Gebauer, H.; Baines, T. Digital servitization business models in ecosystems: A theory of the firm. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, D.; Bican, P.; Brem, A.; Kraus, S.; Clauss, T. Digital platform-based business models—An exploration of critical success factors. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2021, 60, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, P.; Gregori, P. The promise of digital technologies for sustainable entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, W.; Jarrahi, M. The sharing economy and digital platforms: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzella, S.; Fiorentino, R.; Caputo, A.; Lardo, A. Business model innovation in SMEs: The role of boundaries in the digital era. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, A.; Cavallo, A. Agile Business Model Innovation in Digital Entrepreneurship: Lean Startup Approaches. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Santamaría-Velasco, C.; Mahto, R. Intermediaries and social entrepreneurship identity: Implications for business model innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 520–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Guo, A.; Ma, H. Inside the black box: How business model innovation contributes to digital start-up performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacklin, F.; Björkdahl, J.; Wallin, M. Strategies for business model innovation: How firms reel in migrating value. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 82–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. Theory of Economic Development, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Howitt, P.; Howitt, P.; Brant-Collett, M.; García-Peñalosa, C. Endogenous Growth Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R. The Firm, the Market, and the Law; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K. The economic implications of learning by doing. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1962, 29, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Clark, K. Design Rules: The Power of Modularity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tavoletti, E.; Kazemargi, N.; Cerruti, C.; Grieco, C.; Appolloni, A. Business model innovation and digital transformation in global management consulting firms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 612–636. [Google Scholar]

- Huikkola, T.; Kohtamäki, M.; Ylimäki, J. Becoming a smart solution provider: Reconfiguring a product manufacturer’s strategic capabilities and processes to facilitate business model innovation. Technovation 2022, 118, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari-Sadeghi, V.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Candelo, E.; Couturier, J. Exploring the impact of digital transformation on technology entrepreneurship and technological market expansion: The role of technology readiness, exploration and exploitation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trischler, M.; Li-Ying, J. Digital business model innovation: Toward construct clarity and future research directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 17, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocevski, M.; Ghezzi, A.; Arvidsson, N. Exploring the growth challenge of mobile payment platforms: A business model perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 40, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, J.; Walter, Z. Corporate Entrepreneurship, Disruptive Business Model Innovation Adoption, and Its Performance: The Case of the Newspaper Industry. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Blanco, C. How organizational readiness for digital innovation shapes digital business model innovation in family businesses. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 29, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Sustainable Growth Variables by Industry Sectors and Their Influence on Changes in Business Models of SMEs in the Era of Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klos, C.; Spieth, P.; Clauss, T.; Klusmann, C. Digital Transformation of Incumbent Firms: A Business Model Innovation Perspective. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 2017–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latilla, V.; Urbinati, A.; Cavallo, A.; Franzò, S.; Ghezzi, A. Organizational Re-Design for Business Model Innovation while Exploiting Digital Technologies: A Single Case Study of an Energy Company. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2021, 18, 2040002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, X.; Yan, S.; Jiang, Q. Dynamic Capabilities and Business Model Innovation of Platform Enterprise: A Case Study of DiDi Taxi. Sci. Program. 2020, 2020, 8841368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Long, J.; Fan, Q.; Wan, W.; Liu, R. Examining the functionality of digital platform capability in driving B2B firm performance: Evidence from emerging market. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; van Waes, A. When bike sharing business models go bad: Incorporating responsibility into business model innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loonam, J.; O’Regan, N. Global value chains and digital platforms: Implications for strategy. Strateg. Chang. 2022, 31, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhalkina, T.; Cabantous, L. Business Model Innovation: How Iconic Business Models Emerge. In Business Models and Modelling; Advances in Strategic Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2015; Volume 33, pp. 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Tripathi, A. AI business model: An integrative business approach. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A. Digital platforms’ boundaries: The interplay of firm scope, platform sides, and digital interfaces. Long Range Plan. 2021, 54, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. Mapping out the sharing economy: A configurational approach to sharing business modeling. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippel, E. The Sources of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Paiola, M.; Gebauer, H. Internet of things technologies, digital servitization and business model innovation in BtoB manufacturing firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, M.; Miehé, L.; Oghazi, P.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. The evolution of the digital service ecosystem and digital business model innovation in retail: The emergence of meta-ecosystems and the value of physical interactions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 177, 121496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Sjödin; Reim, W. Reviewing Literature on Digitalization, Business Model Innovation, and Sustainable Industry: Past Achievements and Future Promises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.; Gwozdz, W.; Hvass, K. Exploring the Relationship Between Business Model Innovation, Corporate Sustainability, and Organisational Values within the Fashion Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.; McAloone, T.; Pigosso, D. Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G. The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms. In Handbook on Knowledge Management: Knowledge Directions; Holsapple, C.W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Won, D.; Park, K.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X. Growth of a platform business model as an entrepreneurial ecosystem and its effects on regional development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preghenella, N.; Battistella, C. Exploring business models for sustainability: A bibliographic investigation of the literature and future research directions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2505–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyono, A.; Darmawan, B.; Witjaksono, G. How to harnesses digital technologies for pursuing business model innovation: A longitudinal study in creative industries. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachinger, M.; Rauter, R.; Müller, C.; Vorraber, W.; Schirgi, E. Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Passas, I.; Sklavos, G. Investigating the Strategic Role of Digital Transformation Path of SMEs in the Era of COVID-19: A Bibliometric Analysis Using R. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.; Thelen, K. The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism. Politics Soc. 2019, 47, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahut, J.; Iandoli, L.; Teulon, F. The age of digital entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.; Ricart, J. Business model innovation and sources of value creation in low-income markets. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, N.; Satar, M. Exploring business model innovation for competitive advantage: A lesson from an emerging market. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2021, 13, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Exploring the boundaries of open innovation: Evidence from social media mining. Technovation 2023, 119, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, T.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Albino, V. Search and Recombination Process to Innovate: A Review of the Empirical Evidence and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.; Legner, C. Business model tools at the boundary: Exploring communities of practice and knowledge boundaries in business model innovation. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, T.; Öner, M.; Kunday, Ö.; Olcay, G. A journey towards a digital platform business model: A case study in a global tech-company. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 175, 121372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Cheng, B.; Li, A.; Wang, Y.; Yang, N.; Tian, Y. The Impact of Digital Economy on the Economic Growth and the Development Strategies in the post-COVID-19 Era: Evidence from Countries Along the “Belt and Road”. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 856142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonina, C.; Koskinen, K.; Eaton, B.; Gawer, A. Digital platforms for development: Foundations and research agenda. Inf. Syst. J. 2021, 31, 869–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Kulikovskaja, V.; Hubert, M.; Brock, C.; Grewal, D. Effectiveness of engagement initiatives across engagement platforms: A meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 51, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakaki, D.; Chamakiotis, P.; Curto-Millet, D. From ‘making up’ professionals to epistemic colonialism: Digital health platforms in the Global South. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 321, 115787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Li, X. Designing boundary resources in digital government platforms for collaborative service innovation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Guo, M.; Zeng, F.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, T.; Griffin, J. Blockchain-enabled authentication platform for the protection of 3D printing intellectual property: A conceptual framework study. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 2180776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Jovanovic, M.; Visnjic, I. Value Creation and Value Capture Alignment in Business Model Innovation: A Process View on Outcome-Based Business Models. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2020, 37, 158–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G.; Palmer, M.; Truong, Y. Inscribing value on business model innovations: Insights from industrial projects commercializing disruptive digital innovations. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Slovic, S.; Slovic, P.; Tversky, A. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Palmié, M.; Wincent, J. How AI capabilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M. Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M. Business platforms. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Skog, D.; Wimelius, H.; Sandberg, J. Digital Disruption. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2018, 60, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Bocken, N. A call for action: The impact of business model innovation on business ecosystems, society and planet. Long Range Plan. 2022, 55, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hou, F.; Qi, M.; Li, W.; Ji, Y. A Data-Enabled Business Model for a Smart Healthcare Information Service Platform in the Era of Digital Transformation. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5519891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täuscher, K.; Laudien, S. Understanding platform business models: A mixed methods study of marketplaces. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesch, J.; Brillinger, A. The Evaluation Aspect of Digital Business Model Innovation. In Business Model Innovation in the Era of the Internet of Things: Studies on the Aspects of Evaluation, Decision Making and Tooling; Tesch, J.F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini, B.; Cortimiglia, M.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimi, S.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J. Business model innovation in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossotto, C.; Lal Das, P.; Gasol Ramos, E.; Clemente Miranda, E.; Badran, M.; Martinez Licetti, M.; Miralles Murciego, G. Digital platforms: A literature review and policy implications for development. Compet. Regul. Netw. Ind. 2018, 19, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaska, S.; Massaro, M.; Bagarotto, E.; Dal Mas, F. The Digital Transformation of Business Model Innovation: A Structured Literature Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 539363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velu, C.; Jacob, A. Business model innovation and owner–managers: The moderating role of competition. RD Manag. 2016, 46, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Henderson, J.C. Four Vectors of Business Model Innovation: Value Capture in a Network ERA. In From Strategy to Execution: Turning Accelerated Global Change into Opportunity; Pantaleo, D., Pal, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008; pp. 259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G.; Prester, J.; Paré, G. Exploring the boundaries and processes of digital platforms for knowledge work: A review of information systems research. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Han, Y.; Anderson, A.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Digital platforms and SMEs’ business model innovation: Exploring the mediating mechanisms of capability reconfiguration. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 65, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuana, R.; Prasetio, E.; Syarief, R.; Arkeman, Y.; Suroso, A. System Dynamic and Simulation of Business Model Innovation in Digital Companies: An Open Innovation Approach. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliya, S.; Christoph, Z. The Genesis and Metamorphosis of Novelty Imprints: How Business Model Innovation Emerges in Young Ventures. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 554–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; von Delft, S.; Morgan-Thomas, A.; Buck, T. The evolution of platform business models: Exploring competitive battles in the world of platforms. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancillai, C.; Sabatini, A.; Gatti, M.; Perna, A. Digital technology and business model innovation: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 188, 122307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, I. Fintech and regtech: Impact on regulators and banks. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 100, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannerat, H.; Theurillat, T. Old industrial spaces challenged by platformized value-capture 4.0. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreieck, M.; Wiesche, M.; Krcmar, H. Capabilities for value co-creation and value capture in emergent platform ecosystems: A longitudinal case study of SAP’s cloud platform. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 36, 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Perspective | Focus | Source | Term | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market perspective | Emphasis on mediating role and network effect characteristics | [16] | Bilateral Marketplace | Products and services that bring users together in a bilateral network. |

| [10] | Platform Intermediary Marketplace | Interactions between users are influenced by network effects and are facilitated by a public platform provided by one or more intermediaries. | ||

| [6] | Multilateral Platform | Technologies, products, or services that enable direct interaction between two (more) groups of customers or participants. | ||

| Technology perspective | Emphasis on technical architecture and structural features | [17] | Software Platform | An extensible code base based on a software system that provides core functionality and operator interfaces for components that interoperate with it. |

| [18] | Platform | A stable link or foundation to organize the technical development of interchangeable or complementary components and to allow interaction between components. | ||

| [19] | Digital Platform | An extensible digital core that is open to third parties to facilitate improvements or complements. | ||

| Organizational perspective | Emphasis on integration of technical components and social activities | [20] | Platform | Supports interaction between multiple groups of participants and facilitates technology development. |

| [21] | Platform | A layered architecture that combines digital technologies with governance models. | ||

| [22] | Digital Platform | Digital systems that facilitate communication, interaction, and innovation to support economic transactions and social activities. | ||

| Value perspective | Emphasis on value creation, transmission, and acquisition role | [14] | Digital Platform | A collection of digital resources containing services and content that facilitate interaction between external producers and consumers to create value. |

| [22] | Digital Platform | A combination of digital resources that connects multilateral markets through digital technology, enabling producers and consumers to co-create value. | ||

| [15] | Digital Platform | New business innovation logic and value creation paths for participants or consumers through digital technology and infrastructure. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daradkeh, M. Exploring the Boundaries of Success: A Literature Review and Research Agenda on Resource, Complementary, and Ecological Boundaries in Digital Platform Business Model Innovation. Informatics 2023, 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10020041

Daradkeh M. Exploring the Boundaries of Success: A Literature Review and Research Agenda on Resource, Complementary, and Ecological Boundaries in Digital Platform Business Model Innovation. Informatics. 2023; 10(2):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10020041

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaradkeh, Mohammad. 2023. "Exploring the Boundaries of Success: A Literature Review and Research Agenda on Resource, Complementary, and Ecological Boundaries in Digital Platform Business Model Innovation" Informatics 10, no. 2: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10020041

APA StyleDaradkeh, M. (2023). Exploring the Boundaries of Success: A Literature Review and Research Agenda on Resource, Complementary, and Ecological Boundaries in Digital Platform Business Model Innovation. Informatics, 10(2), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10020041

_Bryant.png)