Abstract

In this global era, critical thinking has become crucial for educators and learners. The purpose of this research was to explore how modifying a dialogical strategy in asynchronous online discussion forums impacted Chinese learners’ critical thinking. Due to the Chinese cultural impact of social harmony, the majority of learners tend to maintain silent and avoid critical discussions in instructional settings. The author deployed an affectively supportive model in a modified dialogical strategy to structure Chinese EFL learners’ asynchronous critical postings by probing and questioning while requiring labeling of each cross-referencing posting as Agree/Disagree/Challenge/New Perspective. The participants were two cohorts of similar cultural background but under different political systems in China and Taiwan, here engaged together in cultural interactions. This study employed two research methods: standardized critical thinking tests, and focus groups. Findings reveal that learners in both cohorts indicated some improvement in their critical thinking skills. Nevertheless, there remain affective and cultural issues. Future studies are thus recommended to further investigate the potential of an adaptive model to engage critical discussions with English native speakers and optimize critical thinking for Chinese learners in an EFL environment.

1. Introduction

There has been a trend for Chinese learners to participate in western higher education programs around the world. According to the UK Higher Education Statistics Agency (2014), the top non-UK/non-EU learners were Chinese, with 78,715 new enrolments in tertiary education during 2012–2013. Nevertheless, the majority of learners from a Chinese background tend to keep silent in teacher-student interactions in class, and to avoid critical discussions in public [1,2,3,4]. Yet critical thinking is a cognitive skill which features in Western scholarship, and is particularly needed by English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners [5].

Due to the Chinese cultural influence featuring social harmony and reverence to teacher authority, Chinese learners may not be readily adoptive to the western dialogical model of learning and critical thinking. According to the Vygotsky-inspired social constructivist model, a learner can best develop higher-order thinking by socially constructing knowledge with peers or adults in a suitable cultural context, supported by “scaffolding” [6]. However, a western model of verbalized critical thinking is challenging for Chinese learners [7,8]. There seems to be a significant cultural discrepancy between the western learning style following higher level cognitive aims by a social constructivist model and the eastern style following lower level cognitive aims by practical information impartment [9]. While western critical thinking development has focused on critical skills [10,11], Facione et al. [12] found that affective traits in habits of the mind are also important for the critical thinking skills in the process of critical thinking development. Thus, to develop critical thinking, it is also important to develop an affectively supportive model of shepherd leadership [13] to suit Chinese learners’ affective and cultural needs.

In the current study, the cognitive scaffolding of Chinese learners’ critical thinking followed a modified Socratic questioning strategy in film-based online discussions; this had been proved to be an effective tool to foster EFL learner’s critical thinking [14,15]. To bring together learners with Chinese cultural backgrounds under different political systems, and to encourage cultural interactions, an online forum was set up to enable Chinese EFL learners in China and Taiwan, to conduct asynchronous film-based online discussions for that critical thinking development. The modified dialogical strategy used here entails Socratic probing and questioning [16] with the requirement of labelling the social-cultural interactions as Agree/Disagree/Challenge [17] with the addition of New Perspective. The purpose of this research was thus to explore the impact on EFL Chinese learners’ critical thinking development of the modified dialogical strategy followed in asynchronous discussion forums. Two research questions are as follows:

- To what extent did the Modified Dialogical Strategy foster Chinese EFL learners’ critical thinking in the asynchronous discussion forum?

- How did Chinese learners perceive the Modified Dialogical Strategy in the asynchronous discussion forums? Did they encounter any challenges?

1.1. Definition of Critical Thinking

According to American Philosophy Association [18], critical thinking is a set of cognitive abilities to assess credibility of statements or beliefs for problem solving and decision-making by forming reasoned thinking: judgment in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference within contextual considerations for the reasoning process. This so-called Delphi report [18] on experts’ consensus regarding critical thinking skills was modified by Insight Assessment, The California Critical Thinking Skills Inventory, which features the critical thinking skills of Analysis, Evaluation, Inference, Deduction, Induction, and Overall Reasoning skills [19]. The current study thus chose a similar operational definition of critical thinking as “the ability to analyze, evaluate, infer, deduct, and induct” in given contexts. Investigating how to promote critical thinking in a digital world, the dialogical strategy in play helped Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) transform learners’ depth of thinking by knowledge sharing in a socially constructed online environment [20,21,22,23]. The asynchronous mode in discussions facilitates critical thinking and in-depth reflection as a “mind tool”, due to the time delay for thinking [11]. Compared to the synchronous mode’s spontaneous interactions and immediacy, the asynchronous mode may not create a highly intense free flow of interactions among CSCL participants, yet can better promote critical thinking by its media affordance.

Coupled with the affective trait proposed by Facione [19], online tutors need to understand learners’ individual needs, provide a model path, train group leaders as peer models, and support silent ones for breakthrough, as in shepherd leadership [13]. Therefore, this study chose to deploy a primarily affective support model into asynchronous discussions for critical thinking with the intervention of the modified dialogical strategy in a specific cultural context.

2. Experimental Section

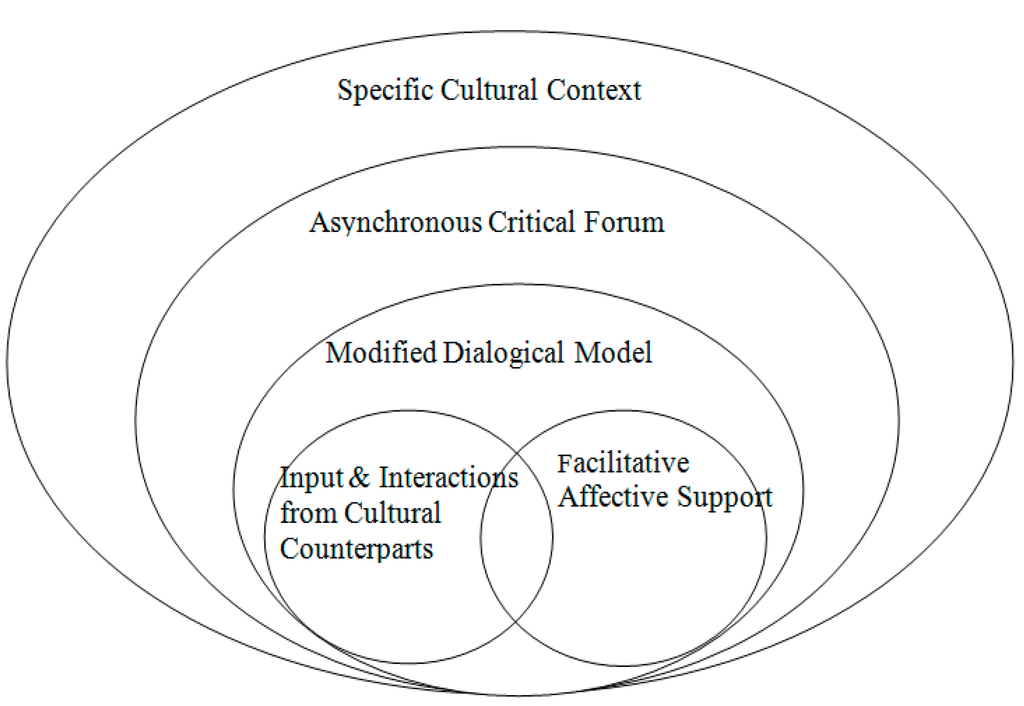

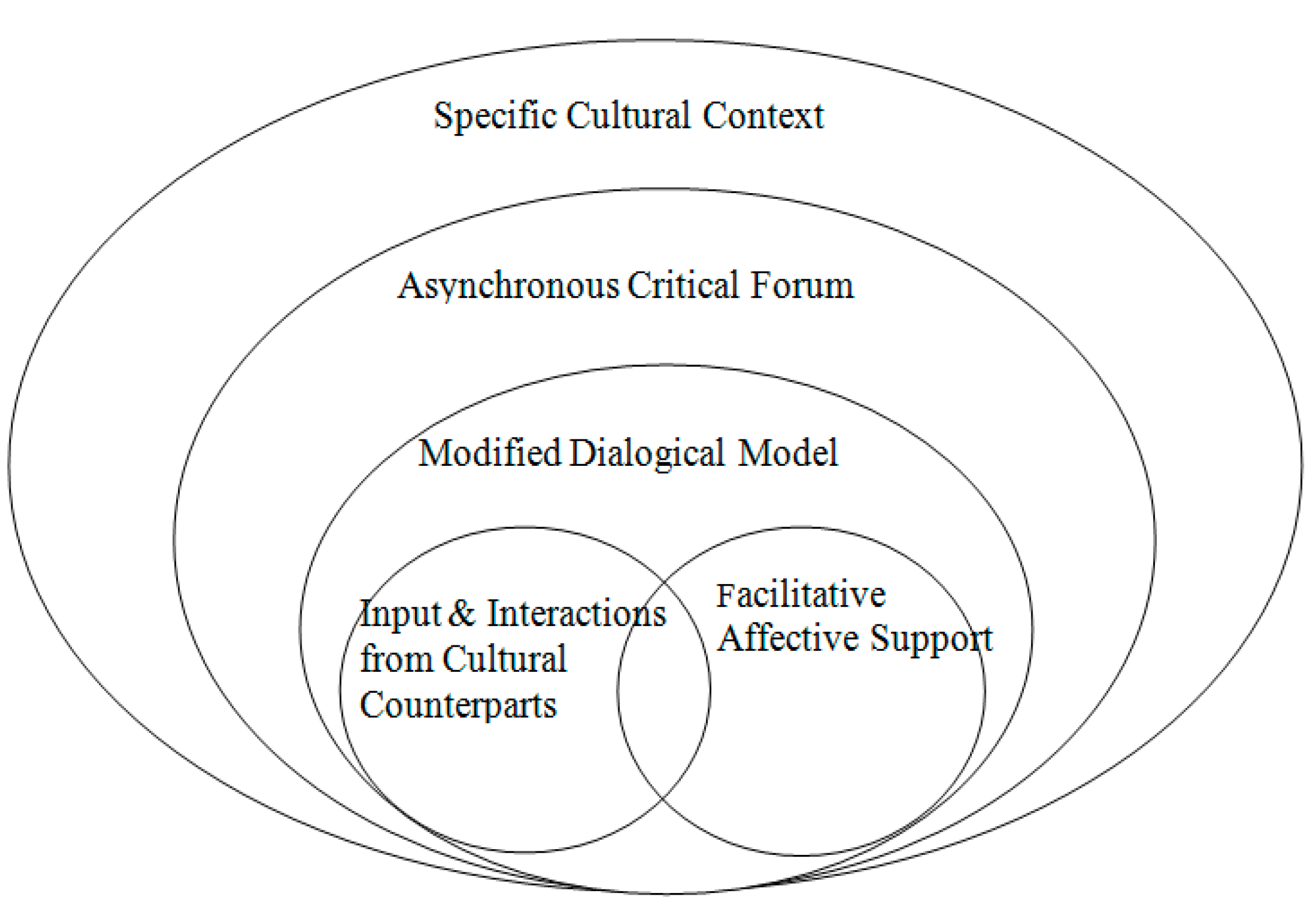

This experiment took place in an asynchronous critical forum in a specific cultural context following the modified dialogical model and bringing together the two cohorts to offer input and interactions, with researcher’s facilitative affective support as shown in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1.

Modified dialogical model.

Diagram 1.

Modified dialogical model.

2.1. Research Participants

The study involved 69 university third-year-equivalent English majors students from two cohorts in Taiwan and Mainland China. There were 43 from a foreign language university in Taiwan, and 26 from a foreign studies university in Beijing, China. For the convenience of the study, the class from Taiwan is called Cohort T, while the class from the People’s Republic of (Mainland) China is termed Cohort M. The majority of the students were female due to the nature of the majors in language and arts. The size of each cohort was the average size of class in each university involved. There were 5 males in Cohort T and 3 males in Cohort M. The participants’ average age was 20–21 in both cohorts. Both cohorts speak similar Mandarin Chinese, but write in different versions of Chinese (classical Chinese in Cohort T and simplified Chinese in Cohort M). These would not have been mutually intelligible if the two cohorts had exchanged their opinions in their own versions of Chinese. It was therefore deemed appropriate and more efficient for them to communicate in English, as they would in any English as a Foreign Language (EFL) class. Their level of English proficiency was the higher-intermediate level of English reading in EFL. Prior to the study, approximately 85% of Cohort T had passed the College Standardized English Proficiency Test benchmark in Taiwan, while 95% of Cohort M had passed their national English proficiency test for university students in China. The students’ writing quality varied from lower-intermediate to intermediate levels.

As far as specific English-language preparation in the language of argument was concerned, not much argumentative writing had featured in training for Cohort T, while Cohort M had received argumentative training in mother tongue early on in their education. Both cohorts had experience of online social networking—MSN, Skype, and school E-Learning for cohort T; and QQ for cohort M, But none of the participants had experienced online discussions providing critical thinking experience prior to the study. Both cohorts participated as combined discussion groups in all four online forums after having watched the films as two groups. The participation was entirely voluntary and class mentors of the two cohorts promised incentive bonus points for online participation to better stimulate the critical online discussion, that might not resonate with their cultural background.

2.2. Research Design

Due to the Internet censorship mechanism operated by the Beijing government [24], discussion content focused on film-based themes, purposely chosen to avoid sensitive political issues. Four rounds of asynchronous discussions involving both cohorts together were targeted on the content of the chosen films, prompted by critical questions selected according to the effective issues for EFL film-based discussions, in order to increase the EFL learners’ degree of collective negotiation and participation [15]. The four issues comprised a societal idea of success, global environment, a family issue, and a cross-cultural communication issue. The researcher provided an overview of the theme, the relevant readings via hyperlinks, and the critical questions for the e-course discussions.

Affective facilitative interventions took place during the actual discussions. Affective and cultural support was also offered unconditional positive encouragement in private emails, mobile phone calls, photo exchanging and gifts like college T-shirts signed with signatures of whole classes. The two cohorts of EFL learners joined in exactly the same asynchronous discussion forums.

The researcher offered facilitative affective support as the “shepherd leader” to both cohorts. Affective support included being encouraging before being critical, exchanges of group photos at sports events, and dumpling making, as well as a synchronous mode of discussion held for rapport building on Moon Festival night in week 2. There were consequent private emails during each forum. The cognitive model was provided and followed, and the researcher reached out to the group leaders as well as to the silent ones who did not participate in the online discussions.

Regarding cognitive modeling with challenging, the facilitator posted questions, supportive and challenging messages according to the operational definitions [19].

In the first phase, participants were invited to respond to fact-based questions: to clarify problem points, to differentiate facts from opinions, and to analyze evidence from different sources [19]. Sample questions in the first forum included:

- What is the problem point of Chris’ family in the American Dream?

- What is assumed in the above opinion?

- If you were Linda, would you have done the same, leaving your husband and little son? Why or why not?

Next, in the second phase, in order to stimulate critical thinking and further increase student-student interaction flow, research participants were required to label message titles with Agree/Disagree/Challenge/New Perspective [16,17], to promote social interactions and cross-referencing by this “dialogical strategy”:

Sample questions for such a discussion of “The Pursuit of Happyness” were as follows

- Label your posting Title with “Agree with evidence” “Disagree with evidence” “Challenge for evidence” and “New perspective”

- Choose a posting by someone from the 'other cohort' to offer comment on, for further one-on-one interactions.

To allow two phases in the discussions, each forum lasted from 3 weeks to 6 weeks depending on the vigor of the discussion, the flow of cross-referencing and the participants’ requests for extension.

2.3. Data Analysis

In line with a broadly social constructivist approach [6], two sources of data were collected and analyzed in the study. The first source was the California Critical Thinking Skill Inventory which provided pretest and posttest scores. The test was administered by the researcher in its Chinese version in week 5 of the first semester, the purpose having first been explained to the participants. The test includes approximately 45 authentic critical thinking items for analysis, evaluation, inference, induction, deduction and overall reasoning categories; the time taken was 40–45 min. The test was retaken later in week 15 of the second semester in order to determine any development in learners’ critical thinking, given their cultural background.

In addition, two focus groups were conducted, one in Beijing in week 10 of the second semester and one in Taiwan in week 11 of the second semester. The aim was to compare against one another to investigate how learners perceived the modified dialogical strategy in the critical asynchronous discussions, and if there were reason for their views, or difficulties in the online discussions—particularly regarding their critical dispositions in agreement, disagreement, and challenging the messages posted in the online discussions (See Appendix 1). All online transcripts were stored in archives to supplement the analysis of critical thinking skills and following up the difficulties mentioned in the focus groups in follow-up analysis. Two research assistants analyzed the labeling of agreement, disagreement, challenging, new perspective [16,17] in the discussion transcripts. The inter-rater reliability was 85% and the researcher discussed any discrepancy with both assistants. To protect participants’ identities, participants were anonymous in filing and analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

The results section is divided into three parts: standardized test results, sample transcripts, and focus group perceptions of the modified dialogical strategy, followed by the discussion.

3.1. Standardized Critical Thinking Test

To answer RQ 1 on the impact of modified dialogical strategy in Chinese learners’ asynchronous online discussions for their critical thinking development, a quantitative summary is presented here. The participants’ critical thinking skills improved in specific sub-skills and also the overall reasoning scores of California Critical Thinking Skills Inventory posttest. Please see Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics on pretest-posttests of California critical thinking skills inventory.

| California Critical Thinking Skills | Pretest Posttest | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Induction | 5.85 | 1.93 | 5.68 | 1.78 |

| Deduction | 5.98 | 1.81 | 7.08 | 1.96 |

| Analysis | 3.70 | 1.35 | 4.05 | 1.29 |

| Inference | 4.66 | 1.41 | 5.00 | 1.76 |

| Evaluation | 5.17 | 1.87 | 5.57 | 1.98 |

| Overall Reasoning | 13.54 | 3.28 | 14.62 | 3.55 |

As shown above, participants’ aggregated total scores increased from 13.52 to 14.62 with most subskills improved. The next table will provide t-test results.

Overall, Table 2 below shows that the participants significantly improved their overall critical thinking (t = 2.36, p = 0.02). Among the sub-skills of critical thinking, while analysis, inference and evaluation only improved slightly and induction did not improve statistically, deduction skill and overall reasoning were found to be significantly better after the training.

Table 2.

Paired-sample T-tests between pretest and posttest.

| Paired Differences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Thinking Skills | Mean | Std. | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | Sig (Two-tail) | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Pair 1 | Induction | −0.11 | 2.28 | 0.35 | −0.82 | 0.59 | −0.33 | 0.73 |

| Pair 2 | Deduction | 1.12 | 1.52 | 0.23 | 0.64 | 1.59 | 4.77 | 0.00 ** |

| Pair 3 | Analysis | 0.31 | 1.20 | 0.19 | −0.06 | 0.68 | 1.67 | 0.10 |

| Pair 4 | Inference | 0.45 | 1.76 | 0.28 | −0.09 | 0.99 | 1.67 | 0.10 |

| Pair 5 | Evaluation | 0.40 | 2.05 | 0.32 | −0.23 | 1.04 | 1.29 | 0.20 |

| Pair 6 | Overall | 1.17 | 3.20 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 2.16 | 2.36 | 0.02 ** |

Regarding the labeling of “Agree, Disagree, Challenge, New Perspective” [16,17], 83% of the postings were labeled, but among those labeled only 14% addressed a different point from the posting in Disagreement, 81% registered Agreement, and 5% New Perspective, with less than 1% Challenge. This followed a traditional cultural practice of Chinese students where the majority of the participants maintained social harmony and cultural comfort zone.

- There were 17% of the total messages left unlabeled: Some participants chose not to label anything by merely typing Q1 or Q2 on the topic line of the posting in order to save time and effort in browsing message flow to decide one’s position in relation to others’ existing posting. All of the four forums exceeded 100 messages, so the later a participant posted, the greater the burden of engaging dialogically.

- New Perspective postings amounted to 5%, apparently because this is a convenient way to be compliant with the online regulations, while yet dismissing the need to browse through all the postings for cross-referencing of dialogues. This label was originally meant to play the role of cross-cultural middle zone to avoid challenge and still make a point publicly and overtly.

- In messages labeled Agreement, it proved fairly easy cognitively to compose a paraphrased message to repeat a fellow classmate’s espoused reasoning behind a statement; and it is culturally acceptable and socially pleasing at the same time to welcome others’ existing reasons, whatever the level of credibility. In non-controversial forums, the rate of self-labeled agreement messages was higher than 81%, appearing similar to the socially popular thumb-up behaviors in online social networks like Facebook.

- Disagreement messages primarily occurred in the controversial forums on environment and marriage. When participants agreed with each other, critical thinking was not stimulated and fostered as much as in disagreement and challenge, where evidence and reasoning ought to be given to create a strong case.

- The 1% of messages labeled Challenge were mildly presented as “agreement and challenge to someone for evidence”, presumably because it is culturally unacceptable and quite an impolite way to address challenge someone who is not Anglo-Saxon. This example will be demonstrated in the next section.

3.2. Participants’ Sample Discussions

The impact of the modified dialogical strategy on critical discussions (RQ1) did moderately change from the monologues in the first round of postings as mere question-answering, to two-way discussions. However, the majority of the participants chose to agree with someone of the same opinion, instead of commenting on an existing posting with a different opinion, again due to the impact of Chinese culture. The researcher in the second phase probed and encouraged real critical discussions with different opinions.

The following illustratively presents a sample of discussions utilizing dialogical strategy in cross-referencing interactions supplemented with operational definitions of critical thinking in a series of four-exchange online discussion between students from each cohort.

In the second forum, after watching “Day after Tomorrow”, a student in Cohort M posted a brief message entitled “New Perspective” on the priority of economy over environment:

| Topic | Environment vs. Economy |

| Posting | No. 79/113 |

| Author | XX from Cohort M |

| Label | New Perspective |

| …I think economy is more important…I think government can merge car corporations to control the car price…The most impressive thing in the film is how fragile human civilization was. No matter what kind of achievements we got, never ever be too proud and look down upon Nature… (No. 79/113) | |

In this example, the author posted a brief statement regarding the priority of economy over environment, yet gave no reason given to support it directly, except (later) attaching an essay on governmental control of car pricing to reduce greenhouse emission. However, in this problem-solution for the economy crisis in the automobile industry, this author attempted to exercise skills of analysis (pointing out a problem point), inference (judging relevant information for plausibility of an alternative) yet without much induction (drawing conclusions by discovering general principles from particular examples) or evaluation (evaluating the merits and the weakness of a given statement) logical discrepancy from the importance of economy to saving the economy. The final sentence covered the point that humility needed to come before nature.

One student from Cohort T, triggered by the first author’s government-control solution, posted an indirect challenge by gently labeled “Agree and Challenge xx for evidence” (No. 80) on

| Topic | Environment vs. Economy |

| Posting | No. 80/113 |

| Author | XX from Cohort T |

| Label | Agree and Challenge xx for evidence |

| Dear xx, I agree with you—climate change can happen abruptly… I agree with you that governments make laws to fix private car prices would discourage private car selling and thus decrease the emission of greenhouse gas. However, now many of the car corporations in the world are closing and need their governments’ support. In this case, will there be any problem while governments are going to make laws to fix prices? Or do you have any plans to avoid disagreement from car corporations? (No. 80/113) | |

The challenge following after the euphemizing agreement was indeed disagreement regarding governmental intervention to control price and reduce emissions. The second author attempted to exercise skills of analysis (pointing out a problem point of climate change), deduction (reaching a conclusion by reasoning from facts of gas emission decrease and the shutdowns in the car industry), inference (judging relevant information for plausibility of an alternative for fixing car prices), and evaluation (evaluate the possible weakness of an alternative). She supplemented the first author’s logical discrepancy regarding fixing car prices and merging car industry, yet without much induction (drawing a conclusion by forming general principles from particular examples), which was the ability with the lowest score in the CCST.

Five days later, the Cohort M student replied in a message entitled “Response to xx”:

| Topic | Environment vs. Economy |

| Posting | No. 108/113 |

| Author | XX from Cohort M |

| Label | Response to xx |

| Dear xx, Thank you a lot for reading my posting and raising some questions. I am very happy to share my ideas with you…If some of those big car corporations like GE failed to tough it out,…plan of fixing a price would work. The second consequences is that the traditional market of car that burn fossil fuels would shrink, and the market of car that powered by green energy like electricity or solar energy would expand. This is just what we want. These are my ideas on this issue. I hope they can help you. (No. 108/113) | |

In the above posting, answering a challenge for evidence, the first author used induction (drawing a conclusion by forming general principles from particular example of GE), analysis (pointing out a problem point about fossil fuel use in cars), inference (judging relevant information for the plausibility of an alternative on fixing car prices), not much deduction, nor evaluation (evaluating the possible weakness of an alternative). The ending to express an “assisting helper’s position” covered the lack of detailed analysis of the issue with reasoning which led to his conclusion. However, in the two cohorts, political systems are different, so the underlying assumptions of values and beliefs are importantly different. In Mainland China, his suggestion of governmental control over price may work, yet would not be possible in a liberal society and capitalistic automobile market in Taiwan.

Eight days later, the Cohort T member furthered her “challenge” in a message tactfully entitled “would like to share more ideas from XX”:

| Topic | Environment vs. Economy |

| Posting | No. 113/113 |

| Author | XX from Cohort T |

| Label | would like to share more ideas from XX |

| Dear XX, Thank you very much for your detailed explanation…May I have more discussions with you and share more of your ideas on this issue? In your reply, you mentioned that if a car corporation fails to tough it out, their assets would be bought by other car manufacturers and the buyer may get their chance to develop into another big corporation. Does this mean that—instead of making bailout plans or trying to save closing car corporations, governments should rather let the worst and painful situation happen, which is, just to let some of the car corporations close? If it has to be so, there might appear a severe problem of unemployment. If we are to solve the unemployment problem raised from the closing of many car corporations, is there any possibility to do it in a harmonious way for both economy and environment, just like what Gore said - solving global warming would produce many work opportunities?…I am looking forward to hearing from you.( No. 113/113) | |

As mentioned above, different ideological assumptions lead to different solutions and arguments regarding government’s role and action—bailout or control. The cohort T student challenge was covered under “Would like to discuss with you more”: a clear deduction based on failure of bailout, consequential analysis and the inference of unemployment after shutdown ending with an evaluation for a possible win-win environmental and more comprehensive solution. The Cohort M student did not reply to this challenging message. This four-exchange discussion exemplified the dialogical approach which is hardly possible in a traditional Chinese EFL class environment.

3.3. Focus Group: Perceptions of Asynchronous Critical Discussion

To answer RQ 2 on Chinese learners’ perception of the Modified Dialogical Strategy in critical asynchronous discussion forums, two focus groups were conducted at the end of the third forum and before the last forum, one each in Beijing and in Taiwan, Chinese learners expressed mixed perceptions of the modified dialogical strategy in asynchronous online discussions and of the shared cultural challenge.

3.3.1. Critical Asynchronous Discussions and Affective Support

Chinese learners in both cohorts confirmed that the critical asynchronous discussions increased their critical thinking overall, but that had depended on the provision of affective support. Focus group members in Cohort T expressed that they would remain “silent in English classes” if there were no film-based online discussions, but that “affective support” from the researcher as tutor helped them to overcome their difficulties in engaging in English critical discussions. Critical online discussions were perceived as quite “direct and sharp” to most Chinese learners, because critical comments can cause a “face loss” issue for the person challenged due to the cultural ideal of social harmony and cultural upbringing.

A member in Cohort T explained, “My critical thinking developed after this new learning style. When our online discussion just started, I got problems in my English writings because I had not much to say or my beginning did not relate to my ending. Sometimes, my ideas did not fit the questions logically, but our teacher was kind to help me with both positive and negative feedback and suggestions, so I was no longer afraid that my answer was wrong. In addition, I also learned how to give feedback to others in English by now.”

Hence there is an important affective need to engage with diffidence and lack of confidence in facilitation to build up Chinese learners’ trust and rapport with the teachers/facilitators before their critical participation. Students believed that this modified dialogical strategy was helpful, partially because of the shepherd leadership and affective support from the researcher/tutor. The online positive reinforcement and affective support in private emailing to group leaders and silent ones expressed as unconditional love were important to motivate learners. They liked to first watch a film and later post their stance embodying critical thinking in English, finally moving beyond merely posting to exchange opinions with others publicly. In addition to teacher support, affective exchange between the two cohorts as mentioned earlier was effective. Focus group results found the shepherd’s affective support by personal private emails, mobile phone calls and photo exchanging was effective—at first emotionally and later cognitively connecting the two cohorts.

A Cohort M student added, “At times, we soon find out the ‘bias’ in our own postings when reading other opinions and challenges. Step by step, we may be more opened up to different opinions, yet I personally still keep my ‘preferred’ opinions even after the exposure to different opinions”. Another student from Cohort M concluded by saying that her critical thinking was developed by online postings facilitated by affective support, which made it “so easy to see my own critical improvement without cramming, unlike for GRE and TOEFL exams…”

The affective support along with the involvement in the critical asynchronous discussions broke through some of the limitations created by cultural boundaries.

3.3.2. Cultural Difficulties in the Modified Dialogical Strategy: Challenge and Disagreement

Regarding the modified dialogical strategy, Chinese EFL learners found cultural difficulties in verbalizing and accepting cognitive challenge and disagreement. The facilitator first probed for evidence and counter evidence, and later sought logical reasoning on diverse sides to support a given stance in an issue. However, when a posting prompted probing comments, it was regarded as wrong or criticized. In the Cohort M’s focus group, where five out of eight learners explicitly expressed their dislike of public disagreement and challenge in their metacognitive comments. Two of them said they would first try to understand the critical comments (critique) calmly and reply if possible. Chinese learners, however, could not readily accept cognitive challenge and disagreement even from their own members or from a tutor.

Similarly, five out of seven Cohort T learners in the focus group said they would use “Agreement” to ask an indirect question in order to challenge, or would simply reply with “New perspective”. Only two of the seven members in Cohort T identified their consistently making direct responses as challenges whenever they disagreed with others’ messages, without being concerned with the “face loss” issue. Here again, critical comments were regarded by most Chinese learners as criticism or personal attack rather than constructive critique or feedback.

Cohort M learners experienced hard feelings from being challenged and disagreed with publicly, and at times harshly. A leading student who did not reply to a Cohort T challenge on China and India’s environmental issue, said: “Challenge messages were not highly welcomed partially because sometimes the messages addressed different parts of a problem point and did not focus on the same base in the online challenge. This made the challenged one hard to further the discussion.”

Similarly, learners from both Cohort T and M preferred to use indirect approaches. A student from Cohort M stated,

I hate disagreement and challenge, so I try to find the common ground to talk about the issue instead of labeling “challenge xx”. Another student added, I use indirect phrases like “Supplementary to XX,” I think there is another aspect of the issue in that…

As shown above, learners from both cohorts overall responded to disagreement by “Agreement” and “New perspective” to actually challenge an existing viewpoint’s perspective. Focus group students said that they have learned to remain as “objective” as possible and to be open to diverse sources of opinions in the modified dialogical discussions.

Overall, many Cohort T students disagreed and challenged members of their own cohort, while Cohort M tended to post messages without answering critical comments or further cross-referencing interactions except this one.

3.4. Discussion

3.4.1. Impact of Modified Dialogical Strategy on Chinese’ Critical Thinking

First of all, participating in asynchronous discussion forums helped the Chinese learners’ critical thinking development—provided they had encouraging affective support. Chinese learners in the study improved their critical thinking after four rounds of critical asynchronous discussion forums. Constructive affective support provided by shepherd leadership is an important issue involved in online critical discussions for Chinese EFL learners. Similar to meeting affective needs in critical thinking [25,26], the affectively supportive “shepherd leadership” model [13] effectively fostered Chinese learners’ confidence to cross cultural boundaries in critical online discussions through the tutor knowing them personally, modeling to them, reaching out to them encouragingly via private emails and online messages. In the focus group, Chinese EFL learners declared that they would remain silent in face-to-face English critical discussion sessions. However, the facilitator’s affective support helped give them motivation and confidence to overcome their fear to publicize opinions in the “direct and possibly threatening” nature of the western model of critical online discussions.

In addition to the protection of the “security veil” of online interaction [27], Chinese EFL learners need assistance other than the language proficiency requirement in engaging in critical English discussions. Mainland Chinese learners started out with clear logical thinking, yet did not then equip themselves with evidence to support their argument; thus EFL faculty can help them to search for credible evidence and analyze an issue based on multiple sources of evidence to reach a well-founded conclusion. These students were stronger in analytical skills, yet weaker in disposition to be open-minded. According to the focus group informants, they could see their own bias if the critical comments were supported with opposing evidence, yet still found responding to critical comments to be challenging. As for the Taiwanese learners, they were strong in identifying problem points and assumptions in their information searching. Nevertheless, while Taiwanese learners’ initial reasoning was often supported by appropriate URLs, they need help and training in compiling persuasive English writing using effective English expressions and demonstrating their logical reasoning process to connect the evidence with the argument. EFL shepherd leaders thus need to help non-English native speakers to write up their critical thinking in highly organized and well-structured English statements. In western writing, the common approach follows a norm of Inverted Pyramid style, which opens up with a clear topic sentence or paragraph embedded with all the major reasons, explanation of reasons and even the conclusion. However, in the norm of the Chinese way of writing composition, a writer’s stance on a given issue and their position do not necessarily need to be stated up front, and may be embedded only in the conclusion. Therefore, critical online discussions in English may need a combination of English reading training to enhance online information searching, and English writing training to help students think and present in the proper logical academic fashion.

3.4.2. Chinese Learners’ Perception of the Film-Based Discussion Forums

Echoing Sampson [15], Chinese participants found film-based discussions effective in triggering their participation and verbalization in the asynchronous discussions, which otherwise would have been unlikely to occur. The themes of societal idea of success, global environment, family issue, and cross-cultural communication issues helped them relate their lives to the English speaking scenarios and stimulate their critical reflection based on their own values. However, due to cultural factors, as Merryfield [27] and Chiu [25] have found, the researched learners encountered some difficulties in applying the dialogical strategy to participate in critical asynchronous discussion forums.

Meanwhile, Chinese participants also met with difficulties in their asynchronous English discussion forums regarding the cognitive rewards of the modified dialogical model. Given the fact that critical thinking is a concept defined in western terms though surely embodying the universal principles of reasoned thinking, overtly critical discussions may require a native westerner to better contextualize Fisher’s [17] dialogical strategy. Focus group informants indicated some cognitive breakthrough in attempting to further agreement messages with others, and in messages expressing reasoning disagreement. Although discussing film-based themes with learners of a different political system was a unique experience, it would also have been helpful to further cross over one’s boundaries by engaging in critical discussions with English native speakers [28]. Chinese participants perceived the modified dialogical strategy in the film-based discussions helpful, yet desired authentic communication in a real life context. Cognitive breakthrough can be more natural and effective if it embodies English native speakers’ cognitive modeling and challenge.

3.4.3. Cultural Difficulties of the Modified Dialogical Strategy for Chinese Critical Thinking

Cultural factors play an important role in the asynchronous interactions. In the west, learners do not need special cultural adaptation to ask a question publicly or to disagree with someone in the constructive and co-operative face-to-face class discussions; yet it is not so in Chinese context. According to the transcripts, the label “Agree with xx” refers to disguised disagreement, while the label “Agree and Question” presents an embedded assertive Challenge. The UK scholar Fisher’s [17] dialogical strategy may be covertly offensive in Asia, instead of effective as in the Anglo-Saxon context where publicly verbalized critical thinking is a culturally accepted norm for cognitive expressions in academic settings. It would not be successful under the Chinese influence where learners culturally opt to silently listen to the knowledgeable authority lecturers’ cognitive input and cognitive modeling. The dialogical strategy in itself de-constructs the Chinese value in risking social harmony by expressing reasoned disagreement which a keen mind has already privately formulated, following or challenging publicly in the process of dialogical intercourses. Unlike the Socratic strategy of the devil’s advocate facilitation suggested by Walker [16], most Chinese learners feel emotionally hurt when others disagree with them and challenge them publicly, which is a violation of social harmony [1,2].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study set out to explore how a modified dialogical strategy impacted Chinese learners’ critical thinking development in asynchronous discussion forums. The study found improvement in standardized critical thinking test results by following online a “dialogical teaching strategy” in critical thinking skills of analysis, evaluation, inference, deduction and overall reasoning skills [19]. Affective support provided by shepherd leadership in being affectively supportive, private emailing and cohort photo exchange was found important. Affective support may include facilitative student leaders to model and care particularly for the silent ones so they can break their zone of comfortable silence to engage in critical discussion. The modified dialogical strategy of labeling Agree/Disagree/Challenge [17] is in need of cultural adaptation to better help Chinese learners participate in critical asynchronous discussion forums according to a western model without fear of possible mistakes. Sessions of culturally appropriate critical thinking definitions and language expressions are recommended to encourage the critical thinking of Chinese learners in asynchronous discussions.

Culture played an important role in online critical thinking improvement, particularly in formulating logical conclusions including affective and cultural considerations [19,27]. Communicating critically with a guest western facilitator may be an alternative to overcome affective issues and compartmentalize cultural violations. Despite the limitations of the small sample size from two cohorts and the similar Chinese background that may not be generalizable to other western learners, EFL learners of a Chinese background need more affective support to apply Fisher [17] and Walker’s [16] cogitatively demanding and culturally inappropriate “dialogical strategy” in English critical asynchronous discussion. Future studies are recommended to investigate “a culturally authentic model” to help go beyond the Chinese comfort zone and to optimize Chinese learners’ critical expressions in the EFL environment.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 97-2410-H-160-012). Special thanks extended to Emeritus Professor John Cowan, and Associate Professor Hsiu-Ting Hung for their insightful advice on earlier drafts of this paper. Thanks for Beijing Foreign Studies University who generously arranged a class for online collaboration yet no faculty was involved in the research and publishing process.

Appendix 1: Focus Group Questions List

- How did you perceive the EFL critical asynchronous discussion forums?

- Was there any cognitive or cultural difficulty in composing a message in a critical asynchronous discussion in the first phase? Why?

- Was there any difficulty in labeling Agree/Disagree/Challenge/New Perspective cross-referencing others in another cohort in a critical asynchronous discussion? Why?

- How did you choose a participant’s posting to comment on? Someone from the other cohort or preferably someone from your own cohort (Taiwanese to comment on Taiwanese and Chinese to comment on Chinese)?

- Did you reply to the agreeing and disagreeing messages directed to you? Why or why not?

- Do you think that the Modified Dialogical Strategy was helpful to your critical thinking?

- How did you perceive the affective support of the researcher in the Modified Dialogical Strategy in the asynchronous discussion forums? Why?

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, W.C. In search of the Chinese in all the wrong places? J. Psychol. Chin. Soc. 2000, 1, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, I.T. Are Chinese teachers authoritative? In Teaching the Chinese Learner: Psychological and Pedagogical Perspectives; Biggs, J.B., Watkins, D.A., Eds.; Comparative education research center, University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, 2001; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A.; Avery, A.; Lai, P. Critical thinking disposition of Hong Kong Chinese and Australian nursing learners. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 44, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.A.; Biggs, J.B. Insights into teaching the Chinese learner. In Teaching the Chinese Learner: Psychological and Pedagogical Perspectives; Watkins, D.A., Biggs, J.B., Eds.; Comparative Education Research Center, University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, 2001; pp. 277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, A.; Shinohara, Y. English additional language and learning empowerment: Conceiving and practicing a transcultural pedagogy and learning. Asian J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2003, 12, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. The genesis of higher mental functions. In The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology; Wertsch, J.V., Ed.; Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.C.; Lee, C.H. A preliminary inquiry for rationality theories and critical thinking education in Taiwan. J. Sci. Technol. 2002, 11, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, J.H.; Chen, L. Cultural values and argumentative orientations for Chinese people in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China. In Intercultural Communication: A Global Reader; Jandt, F.E., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Scollon, S. Not to waste words or students: Confucian and Socratic discourse in the tertiary classroom. In Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Hinkel, E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, T. D. National Postsecondary Education Cooperative Sourcebook on Assessment, Vol.1: Definitions and assessment methods for critical thinking, problem-solving and writing; No. NPEC2000195; ED Pubs: Jessup, ND, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen, D.H. Computers as Mindtools for Schools: Engaging Critical Thinking; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Facione, P.A.; Sanchez, C.A.; Facione, N.C.; Gainen, J. The disposition toward critical thinking. J. Gen. Educ. 1995, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, B.; Davenport, D. Shepherd Leadership: Wisdom for Leaders from Psalm 23; Apocalypse Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, R.K. The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R. Utilizing Film to Enhance Student Discussion of Sociocultural Issues. Internet TESL Journal. 2009, 15. 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.A. Socratic strategies and devil’s advocacy in synchronous CMC debate. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2004, 20, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R. Dialogic teaching: Developing thinking and metacognition through philosophical discussion. Early Child Dev. Care 2007, 177, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, P.A. Executive Summary: Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction; The California Academic Press: Millbrae, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Facione, P. Think Critically; Pearson Education: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aalst, J.V. Distinguishing knowledge-sharing, knowledge-construction, and knowledge-creation discourses. Int. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn. 2009, 4, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, R. Dialogic: Education for the Internet Age; Routlege: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, R. Dialogic education and technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, N.; Wegerif, R. Is “exploratory talk” productive talk? In Learning with Computers: Analysing Productive Talk; Littleton, K., Light, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.Y. China launches golden shield censorship to monitor all population. Lib. Times 2009. A1. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Y.-C.J. Facilitating Asian learners’ critical thinking in online discussions. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 40, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipman, M. Thinking in Education; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Merryfield, M. Like a veil: Cross-cultural experiential learning online. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2003, 3, 146–171. [Google Scholar]

- Scarino, A.; Crichton, J.; Woods, M. The role of language and culture in open learning in international collaborative programs. Open Learning 2007, 22, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).