Abstract

This study is aimed at estimation of the exchange rate volatility and its impact on the business cycle fluctuations in four central and eastern European countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania). Exchange rate volatility is estimated with the EGARCH(1,1) model. It is found that exchange rate volatility is affected by the components of the Index of Economic Freedom from the Heritage Foundation, besides inflation and crisis developments. The empirical results using GMM estimation technique and comprehensive robustness checks suggest that exchange rate volatility reduces the risk of recession in the Czech Republic while the opposite effect is found for Hungary and Romania, with a neutrality for Poland. These findings continue to hold after controlling for the fiscal and monetary policy indicators. There is evidence that the RER undervaluation prevents sliding into a recession on a credible basis in Poland only, with a neutral stance for other countries. Except in Romania, higher levels of economic freedom is associated with worsening of the cyclical position of output. Among other results, stabilization policies in the recession imply fiscal tightening for the Czech Republic and Romania, higher money supply for the Czech Republic and Poland, and lower central bank reference rate for Hungary.

1. Introduction

Exchange rate volatility represents short-term fluctuations of nominal (real) exchange rates about their longer-term trends, while currency misalignment refers to a significant deviation of the actual real exchange rate (RER) from its equilibrium level (Frenkel and Goldstein 1991). Generally, variability of RERs reflects variability of nominal exchange rates. Empirical results on the exchange rate volatility effects on economic growth are rather ambiguous, being sensitive to the choice of estimators, control variables, the time period and the sample taken under consideration, country-specific factors or the sample of countries chosen (for panel studies) (Boar 2010).

Some empirical studies do not find any significant link between exchange rate volatility and economic performance (Ghosh et al. 2003). Other studies are in support of causality between exchange rate volatility and economic growth, with both positive and negative effects being observed. Favorable effects of exchange rate flexibility are found by Edwards and Levy-Yeyati (2005). However, evidence of a negative relationship between exchange rate volatility and economic growth is found for developed and industrial countries (Holland et al. 2013; Jamil et al. 2012; Janus and Riera-Crichton 2015; Papadamou et al. 2016), middle-income countries (Aizenman et al. 2018), as well as developing ones (Dollar 1992). Other studies are rather ambiguous. For example, Bleaney and Greenaway (2001) found for 14 sub-Saharan African countries that volatility exerts negative effects on investment but not on economic growth. Another study of 125 countries finds that exchange rate fluctuation has different effects on economic growth in different countries (Han 2020). Schnabl (2009) highlights the negative effect of volatility on economic growth in several European and Asian countries. Similar results are obtained for the CEE countries by Arratibel et al. (2011); Boar (2010); and Morina et al. (2020).

For developing and emerging countries, volatility seems to be more harmful under a flexible exchange rate regime and financial openness (Barguellil et al. 2018). However, Furceri and Zdzienicka (2012) and Tsangarides (2012) found that countries with a more flexible exchange rate regime tend to experience lower production losses during periods of financial crises. As argued by Schnabl (2009), the mixed results on the link between exchange rate volatility and economic growth can be explained by the country-specific factors such as the level of financial markets development, human capital endowments, as well as institutional features.

Most studies employ conditional volatility measures, for example Antonakakis and Darby (2012); Holland et al. (2013); and Jamil et al. (2012), including studies for the central and eastern European (CEE) countries (Firdmuc and Horváth 2007; Miletić 2015). As alternative measures for exchange rate volatility, standard deviations of monthly exchange rate changes or percent exchange rate changes are used as well (Caporale et al. 2011; Janus and Riera-Crichton 2015; Hau 2002; Morina et al. 2020; Schnabl 2009).

Among controlling variables, the real exchange rate (RER) misalignment and institutional features are worth attention. A number of studies indicate that a more depreciated (undervalued) exchange rate is favorable for economic growth (Béreau et al. 2012; Hausmann et al. 2005), especially for developing and emerging countries (MacDonald and Vieira 2010), though opposite results are not lacking as well (Ahmed et al. 2002; Karadam and Ozmen 2016; Morvillier 2020; Ribero et al. 2020). For nine CEE economies, it is found that exchange rate overvaluation has a negative impact on economic growth, with a stronger effect than undervaluation (Cuestas et al. 2019).

Most of the empirical studies provide evidence that institutions matter for economic growth both in general and in a host of interesting specific contexts (Durlauf 2018). Particularly, there is a positive link between economic freedom and economic performance (De Haan and Sturm 2000), including CEE countries (Uzelac et al. 2020), though not all aspects of economic freedom affect economic growth (Justesen 2008).

This study is aimed at estimation of the exchange rate volatility and its impact on the output fluctuations in four CEE countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania). The Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity (GARCH) method is used to model exchange rate volatility and the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) is used to examine the effect of exchange rate volatility on the business cycle. Our main contribution lies in adopting a more comprehensive approach in studying output effects of exchange rate volatility by integrating volatility and currency misalignment with institutional dimensions.

2. Literature Survey

2.1. Exchange Rate Volatility and Economic Growth

Exchange rate volatility has advantages in the case of adjustment to real asymmetric shocks, as there is no need for slow and costly real exchange rate adjustments to be carried out through relative price and productivity changes under price and wage rigidities, as is the case for a fixed exchange rate regime (Edwards and Levy-Yeyati 2005). For small countries, pegging of a currency may lead to its overvaluation and currency crises, magnifying the effects of asymmetric shocks (Edwards 2011). Besides absorbing properties or resilience to currency crises, a switch to free or managed floating is motivated by high capital mobility and financial innovations (Boar 2010).

Traditional view of the exchange rate as a shock absorber that substitutes for the lack of nominal price flexibility implies a higher volatility in the face of real shocks, especially foreign ones. As argued by Devereux and Engel (2002), exchange rates may be highly volatile because they reflect monetary factors and have little effect on macroeconomic variability:

where is the nominal exchange rate measured as the price of foreign currency in terms of domestic currency (a rise in means a nominal depreciation), and are domestic and foreign money supply, respectively, measures bias in the conditional forecasts of the future exchange rate, is the discount factor, and are shares of profit due to distribution of domestic and foreign products.

Excess volatility is presented as follows:

where is the coefficient of proportionality between the conditional variance of the exchange rate and the conditional variance of . Exchange rate volatility depends only on the volatility in relative money supply and becomes much higher than shocks to economic fundamentals, thus creating “disconnect” from the rest of the economy.

Addressing the latest phenomenon of extremely low short-term interest rates, Corsetti et al. (2017) in a tractable model show that a float has advantages in the case of deflationary demand shocks abroad as it is necessary to offset not only the collapse in external demand but deflation abroad as well. Formally, expression for the equilibrium exchange rate presents as follows:

where and , and are domestic and foreign nominal interest rates and price inflation, respectively, and are the price indices of domestically produced goods and consumer prices abroad, respectively, and is the expectations operator. Equation (3) implies that present nominal exchange rate depends on the future gaps in real interest rates and the lagged term of trade. If there is a liquidity trap, the domestic currency depreciates in nominal and real terms thus insulating from domestic economy from foreign deflationary pressure.

While the “exchange rate disconnect” implies that the exchange rate volatility depends only on fundamentals, such as the relative money supply, the interest rate and output growth differentials, or terms of trade, is downplayed by the scapegoat theory of exchange rates. It is argued by Bacchetta and van Wincoop (2013) that changes in the exchange rate are dependent not only on some observable fundamentals but on changes in expectations of structural parameters as well:

where is the vector of time-varying true structural parameters, is the vector of expected parameters at time t, is the unobserved fundamental, and is the discount factor . As investors do not know the value of true structural parameters and their time variation in the short- to medium term, it becomes a source of exchange rate volatility. Empirical support for the scapegoat theory is claimed by Fratzscher et al. (2015).

As excessive exchange rate fluctuations can be limited by stabilization policies, Corsetti (2006) demonstrates that the exchange rate volatility implied by optimal stabilization rules is inversely related to the import content of consumption. Although a floating exchange rate is indeed associated with higher volatility for both the nominal and the real exchange rate (Mussa 1986; Petracchi 2021), it cannot be a source of concern. As explained by Krugman (1988), the volatility of exchange rates in combination with the substantial sunk costs associated with entering a foreign market made foreign trade prices and volumes unresponsive to exchange rate fluctuations, with the real sector becoming insensitive to exchange rate fluctuations.

Another argument in favor of greater exchange rate flexibility/volatility is the monetary policy autonomy in the presence of strong international capital mobility that offer the possibility of stabilizing the domestic economy (Dornbusch and Giovannini 1990). As implicit in the Redux model, money supply shocks can have real effects even in the long run, but at the cost of higher exchange rate volatility (Obstfeld and Rogoff 1995). It is not a problem if exchange rate volatility is expansionary or at least neutral in respect to output, but it can be a problem otherwise.

A fixed exchange rate regime is not without advantages of its own. For small open economies, stable exchange rates provide better insulation against nominal shocks (McKinnon 1963). If exchange rate stability contributes to macroeconomic stability, it creates a favorable environment for investment, consumption, and growth. Straub and Tchakarov (2004) demonstrate that in a model with habit persistence, even non-fundamental exchange rate volatility that generates only small variation in prices and interest rates might induce economically significant welfare changes. In a theoretical model by Devereux and Lane (2003), external debt reduces the efficiency of the exchange rate in responding to external shocks. Also, exchange rate flexibility can be a source of inefficiency due to the presence of speculative actions (Boar 2010).

As surveyed by Arratibel et al. (2011); Demir (2013); Eichler and Littke (2017); and Juhro and Phan (2018), exchange rate volatility has negative effects on economic growth through numerous channels, including lower efficiency of price mechanisms at international level; higher risk premium; greater uncertainty on future consumption and firm revenues; uncertainty about export revenues; increased volatility of business profitability; higher risk for domestic and foreign direct investment, particularly in developing economies; increased inflation uncertainty and higher interest rates along with reduced investment and consumption; obstacles to consumption risk sharing due to the home-bias in portfolio investment; adverse effect of credit constraints on domestic investments; and changes in production cost and increased international transaction risk, or in the relative costs of production with both creative and destructive growth effects. Although exchange rate flexibility reduces the sensitivity of local to base-country central bank policy rates, this feature is weakened by the balance sheet effect because a depreciation of the local currency would raise the cost of servicing and rolling over foreign-currency debt and bank loans (Georgiadis and Zhu 2019). Also, liability dollarization amplifies a negative impact of exchange rate flexibility on growth (Benhima 2012).

Within the framework of a simple monetary growth model, it is demonstrated by Aghion et al. (2009) that for countries with relatively low levels of financial development, (real) exchange rate uncertainty exacerbates the negative investment effects of domestic credit market constraints. An increase in exchange rate volatility may discourage firms from creating jobs as well (Belke and Setzer 2003). Similar to Demir (2013). It is possible to argue that numerous transmission channels imply that growth effects of exchange rate volatility will ultimately depend on the country.

2.2. Currency Misalignments in Open Economies

Another strand of the literature refers to effects of (real) exchange rate misalignment, especially in the context of the business cycle. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, excessive capital inflows may lead to acceleration of inflation and economy overheating, with a risk of recession and costly stabilization efforts to follow. However, flexible rates quite often are not used to play a stabilizing countercyclical role; instead, central banks engineer systemic overvaluation in the context of inflation targeting (Dornbusch 2001).

On the other hand, the fear of exchange rate appreciation under a floating exchange rate regime may be no less damaging than excessive exchange rate stability. As demonstrated by Caballero and Lorenzoni (2014), persistent RER overvaluation can be harmful for the economies with a financially constrained export sector if it is followed by a large exchange rate overshooting once the factors behind the appreciation subside. Such a situation requires exchange rate interventions. Undervaluation can promote growth by stimulating technological progress and knowledge spillovers, but at the cost of negative distributional effects (Ribero et al. 2020). Although a flexible exchange rate regime allows for maintaining a competitive (undervalued) exchange rate in order to boost exports and growth, this kind of policy is difficult to sustain, except for low-income countries, and only in the medium term (Haddad and Pancaro 2010). Such findings are consistent with a more general view that currency misalignments are inefficient and lead to lower welfare (Engel 2011).

The relationship between exchange rate and economic performance can be dependent on institutional factors. Rodrik (2008) argues that there is a trade-off between a currency undervaluation and quality of institutions: a weaker currency is needed in order to compensate for inefficient institutions. As mentioned by Schnabl (2009), the answer to whether flexible exchange rates would reduce the risk of crisis depends on the central bank’s response to appreciation pressure. Only if the central bank allows for “uncontrolled appreciation” of the domestic currency does the probability of crisis decline, because the sharp appreciation of the domestic currency deteriorates the economic outlook. The effect of central bank transparency on exchange rate volatility depends on the development of countries (Weber 2017).

2.3. Sources of Exchange Rate Volatility

The exchange rate volatility tends to be lower in more open economies with higher GDP per capita and lower inflation (Bleaney and Francisco 2010) than developing countries with high levels of external debt (Devereux and Lane 2003). Both free floating and more volatile terms-of-trade contribute to higher volatility. Other sources of (real) exchange rate volatility in both industrial and developing countries include highly volatile productivity shocks, sharp oscillations in monetary and fiscal policy shocks, and financial openness (Calderon and Kubota 2018). The link between liquidity and exchange rate volatility depends on the level of financial development (Pham 2018). The exchange rate volatility can be increased by the foreign exchange interventions by central banks (Frenkel et al. 2005) or global economic uncertainty (Juhro and Phan 2018).

Higher exchange rate volatility in the CEE countries is associated with a more flexible exchange rate regime and use of interest rate as a key instrument of monetary policy (Kočenda and Valachy 2006) or low credibility of exchange rate management (Firdmuc and Horváth 2007). Giannellis and Papadopoulos (2011) found that volatility of Polish and Hungarian currencies is caused by the monetary-side of the economy. As established by Lyócsa et al. (2016), the Czech koruna and Polish zloty appear to be more vulnerable to local and global spillovers than the Hungarian forint. The global financial crisis of 2008–2009 increased volatility of the exchange rate in the Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania (Miletić 2015).

Institutional factors can be behind exchange rate volatility as well. For example, Eichler and Littke (2017) propose a theoretical model and provide empirical evidence that better information about monetary policy objectives decreases exchange rate volatility, with a more pronounced effect for countries with a lower level of central bank conservatism. While there is no effect of central bank transparency for developing countries, transparency increases exchange rate fluctuations in developed countries (Weber 2017). Based on the panel estimations for 39 countries from Latin America, Asia, and MENA, it is argued that financial liberalization and integration should be pursued only gradually in emerging countries in order to decrease real exchange rate volatility (Caporale et al. 2011). However, the balance sheet effect implies that it may be optimal for monetary authorities to diminish exchange rate variation in order to decrease the cost of servicing and rolling-over foreign-currency debt (Georgiadis and Zhu 2019).

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

For the purpose of this study, we use data for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania over the period of 2000–2019. All these countries follow free or managed floating exchange rate policies which makes it highly relevant for the study of a nominal exchange rate volatility. Quarterly series of the real gross domestic product (index, 2010 = 100), nominal and real effective exchange rates (index, 2010 = 100), as well as on the central bank reference rate (%), money aggregate M3 (in local currency), and the budget balance (% of GDP) are obtained from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics database (www.data.imf.org, accessed on 8 February 2021). As measures of institutional quality, the Index of Economic Freedom from the Heritage Foundation is used (www.heritage.org/index/dowload, accessed on 8 February 2021).

The cyclical components of real output, yct (%), as well of the currency misalignment, rerct (%), were calculated as a percentage deviation of the current values from the Hodrick-Prescott filtered trend. The use of a nominal effective exchange rate, et, is preferred in studies of the exchange rate variability because the RER variability incorporates price fluctuations, which represent another type of uncertainty for private agents (Barguellil et al. 2018). Other studies implement alternative measures of the currency misalignment. For example, Rodrik (2008) and Ribero et al. (2020) define RER misalignment as a difference between exchange rate adjusted for PPP conversion factors, , and the RER obtained from a regression on the log the GDP per capita: .

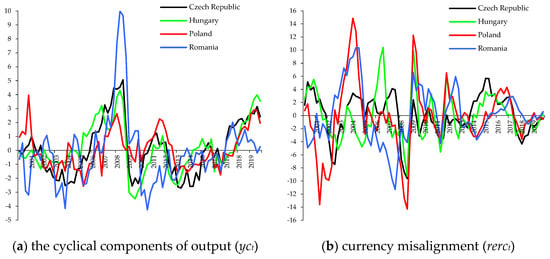

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the main variables that are investigated in our study. Romania is characterized by the largest cyclical peak of its output fluctuations at almost 10%, with the deepest trough at −4.3% as well. The cyclical components of real output reveal less instability in the Czech Republic and Hungary. The business cycle is much smoother in Poland, probably due to a very flat slowdown in 2009. However, Poland reveals the highest level of the currency misalignment, followed by Romania, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Outcomes are similar for the NEER in first differences. As suggested by the Jarque-Bera statistics, all NEERs show evidence of non-normality. It is not surprising as the NEER is determined by random changes in bilateral exchange rates, including countries with high-risk currencies. Except for Romania, cyclical components of output are normally distributed.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Figure 1 visualizes developments in the cyclical components of output and currency misalignment for the CEE countries. Business cycles of the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland seem to be quite synchronized, with cyclical output developments in Romania being somewhat different in terms of timing and amplitude. All countries experienced a boom in 2007–2008 followed by a remarkable slowdown in 2009–2010 (except Poland). After a period of anemic growth in 2013–2016, output dynamics have accelerated, though to a lesser extent in Romania. Currency misalignments had been more substantial in the 2000s, especially for the Polish zloty and the Romanian lei. On the eve of the world financial crisis there had been a remarkable appreciation of the CEE currencies in 2007–2008, with a steep reverse to follow in 2009. As recently, NEERs have been fluctuating approximately ±5% all around the equilibrium trend.

Figure 1.

Business cycle and currency misalignment, 2000–2019 (in %). Source: own calculations based on data from IMF International Financial Statistics (www.data.imf.org, accessed on 8 February 2021).

The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) stationarity test indicates that both cyclical components of output and currency misalignment variables are stationary in levels at the 5% significance level (Table 2). As expected, the NEERs are stationary in first differences.

Table 2.

Unit root test.

Similar to Borys et al. (2008), to measure the quality of domestic institutions and the progress of market reforms we use the Heritage Foundation database. Besides the composite Index of Economic Freedom (heritaget), we consider nine sub-indices, namely business freedom (1), trade freedom (2), investment freedom (3), financial freedom (4), property rights (5), fiscal health (6), judicial effectiveness (7), labor freedom (8), and monetary freedom (9), ranging from 0 to 10 points. The importance of institutions used to be considered in the context of long-term growth, but it seems to be of the same role in managing short-term output fluctuations. As mentioned by Boar (2010), the key to the macroeconomic success of an emerging economy is not the initial choice of the exchange rate regime but rather the health of the fundamental institutions.

3.2. The Model of Exchange Rate Volatility

The merit of the GARCH model stems from its ability to differentiate and recognize information that generates the exchange rate in a random process. The GARCH model is a robust model that is capable of dealing with the volatility associated with financial data characterized by skewed distribution and the problem of heteroscedasticity. In addition, the GARCH model allows for the differentiation and recognition of information that generates the exchange rate in a random process (Azid et al. 2005). Alternative measures of volatility such as the standard deviation and the coefficient of variation do not take into account the exchange rate uncertainty, which represents the unobserved fraction of exchange rate fluctuations (Barguellil et al. 2018).

In the baseline model, the quarterly exchange rate volatility is specified as follows:

where is the nominal effective exchange rate, is the information set available at time , is the stochastic factor, and ∆ is the operator of first differences. The expected value of exchange rate is modelled as ARMA(p,q) process.

For the purpose of our study, ARMA(2,2) model is used. In line with Corsetti et al. (2017), the interest rate differential between foreign and domestic rates, as well as the lagged terms of trade, are included as explanatory variables too. Foreign interest rate, , is proxied by the 6-month LIBOR. As a measure of the domestic interest rate, , the money market rate is used for Poland and the lending rate is used for other CEE countries. The price index of domestically produced goods, , is proxied by the producer prices, with consumer prices in Germany being used as a measure of foreign prices, .

A one-period ahead forecast variance, σt, is a function of the mean (ω), the ARCH term (α), the EGARCH term (), and three explanatory variables. A high value of means significant impact of stochastic shocks, with a high value of reflecting persistence in exchange rate volatility. The sum of both coefficients (α and β) indicates the speed of convergence of the forecast of the conditional volatility to a steady state (Kočenda and Valachy 2006). Asymmetry in the standardized shocks to exists if , why leverage exists if and (McAleer and Hafner 2014). Similar to Schnabl (2009), we used the consumer price index (CPI) as a proxy for macroeconomic stability. A country-specific dummy CRISISt is supposed to control for asymmetric shocks.

In the extended model, we test the link between exchange rate volatility and institutional features, as measured by the composite Index of Economic Freedom (heritaget) and its sub-indices. As data on the Index of Economic Freedom are provided on the annual basis, we used procedure of the Holt-Winters exponential smoothing in order to obtain time series in the quarterly window.

3.3. The Model of Business Cycle

A general representation for the cyclical components of real output model is given as follows:

where is the cyclical component of real output in the Eurozone (%), are alternative measures of exchange rate volatility (k), is the composite index of economic freedom as provided by the Heritage Foundation, is the trade balance (% of GDP), is the dummy for entering the European Union, and is the stochastic factor.

Our regression model incorporates both exchange rate volatility around a constant level and the currency misalignment interpreted as a percentage deviation of the observed RER from the Hodrick-Prescott trend. Other explanatory variables include the Eurozone business cycle, the composite Index of Economic Freedom, the trade balance and the dummy for EU accession. The trade balance accounts for external factors that can affect the cyclical components of real output. A dummy for the EU accession is included as an explanatory variable that accounts for effects of economic integration of the CEE countries. Similar to the country-specific cyclical components of real output, business cycle for the Eurozone is obtained with the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

As suggested by De Haan et al. (2006), a measure of economic freedom is used both in levels and first differences. It is demonstrated that such a specification explains significantly more of the variation in economic growth. While most of empirical studies confirm a positive relationship between all areas of economic freedom and economic growth, for example Doucouliagos and Ulubasoglu (2006) or Emara and Reyes (2020), it is not straightforward whether more of economic freedom is helpful to the same extent in stabilizing cyclical fluctuations of economy. Bjørnskov (2016) finds that crisis risk and duration are not affected by economic freedom, but it has an effect on the peak-to-trough GDP ratios and recovery times of crises.

Two measures of volatility are employed, as presented above. Conditional variance from the baseline model, , accounts for domestic consumer prices and crisis developments as external factors. On the other hand, conditional variance from the extended model, , reflects impact of the Index of Economic Freedom across its nine sub-indices.

In the extended model, we add the budget balance, budgett (% of GDP), and two measures of monetary policy, i.e., excess money supply, moneyct (%), and the central bank reference rate, rcbt (%), to the list of explanatory variables. Excess money supply is calculated as a difference between money aggregate M3 and its trend obtained with the Hodrick-Prescott filter. While the use of the central bank reference rate reflects a standard monetary policy tool under a floating exchange rate regime, the excess money supply can control for attempts by the central bank to sterilize capital flows.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Determinants of Exchange Rate Volatility

As the Jarque-Bera test implies non-normal error distribution for ∆et, we use EGARCH(1,1) models with the asymmetric Student’s t-distribution. Estimates of the baseline model are presented in Table 3. Among determinants of the mean exchange rate, the interest rate differential is associated with depreciation for three out of four countries, being in line with the logic of Equation (3). However, the relationship for Romania is just the opposite. As for the lagged terms-of-trade, there is no evidence of a direct link between higher domestic prices and depreciation. For the Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania, there is an inverse relationship between both variables. Contrary to predictions of Corsetti et al. (2017), deflation abroad does not lead to depreciation of the exchange rate.

Table 3.

Univariate EGARCH results (baseline model).

The ARCH term () indicates that impact of “surprises” from previous periods is the strongest in the Czech Republic and Poland (higher than one implies that shocks to exchange rate can destabilize its volatility), with a much weaker effect in Hungary and Romania. Based on the value of the EGARCH term (), persistence of exchange rate volatility is observed at the statistically significant level in the Czech Republic only. As indicated by the sum of α and β, the speed of convergence of the forecast of the conditional volatility to a steady state is very slow in the Czech Republic and Poland. The standardized shocks to are symmetrical in Poland, as the value of is not statistically different from zero. For the Czech Republic and Romania, the negative value of implies that negative news affects the exchange rate volatility more heavily than positive news. It is just the opposite in Hungary. No preconditions for leverage are met in any country.

Among the control variables, inflation contributes to exchange rate volatility in the Czech Republic and Romania, though with opposite signs. There is no difference between all four CEE countries in that crisis developments are associated with higher exchange rate volatility.

In the extended model (Table 4), a statistically significant direct relationship between the lagged terms-of-trade and mean exchange rate emerges in Hungary. The ARCH effect somewhat decreases in Poland and Romania, with the opposite outcome observed in the Czech Republic and Hungary. As suggested by the value of β, there are no changes to the assessment of persistence in exchange rate volatility in the Czech Republic. However, exchange rate variability becomes more persistent in Hungary. Considering the sum of ARCH and EGARCH coefficients, a control for institutional features implies a significantly slower speed of convergence of the forecast of the conditional volatility to a steady state in Hungary. For other countries, changes are rather marginal. Asymmetry of the standardized shocks to is confirmed for Hungary and Romania, while the negative coefficient of becomes insignificant for the Czech Republic. Among other changes, inflation becomes a factor behind lower exchange rate volatility in Hungary. Except the Czech Republic, the coefficient of becomes significantly lower for other countries.

Table 4.

Univariate EGARCH results (extended model).

As suggested by the estimated coefficients on sub-indices of economic freedom, in a more liberal environment exchange rate volatility becomes lower. The only exception is Hungary, where monetary freedom brings about a higher exchange rate volatility. On the whole, the effects of economic freedom on exchange rate volatility are country specific. Property rights guarantees decrease exchange rate volatility in Romania. Fiscal health exerts the same effect on volatility in Hungary. Success in anticorruption activities contributes to a lower exchange rate volatility the Czech Republic and Poland. In the extended model, inflation becomes a volatility-decreasing factor in Poland, with a positive coefficient on changing sign. No changes in the effects of crisis developments are observed.

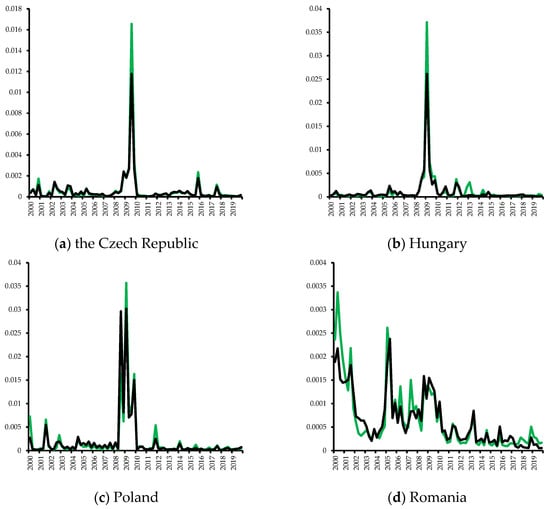

Figure 2 plots the evolution of quarterly exchange rate volatility by country, with the conditional variation obtained by fitting the baseline and extended EGARCH(1,1) models in green and black colors, respectively. For all countries, periods of low volatility are followed by periods of high volatility which could be associated with periods of global financial crisis of 2008–2009 and/or domestic financial turmoil (the Czech Republic in 2001–2002, Hungary in 2012–2013, Romania in 2004–2005). Differences between two measures of exchange rate volatility seem to be quite small in the Czech Republic and Hungary, while being more pronounced in Poland and Romania. After controlling for the institutional features, volatility becomes somewhat smaller. Except Romania, the exchange rate volatility rose from the beginning of 2007, with a peak during the world financial crisis of 2008–2009. Volatility then subsided in the majority of CEE countries, except Hungary in 2012–2013. For Romania, there is an increase in volatility around 2005 that is followed by a smaller jump in 2008–2009.

Figure 2.

Conditional variance from EGARCH(1,1) Model.

To summarize, volatility patterns of the CEE countries seem to be similar in respect to both ARCH and EGARCH effects, especially after controlling for the institutional features. However, there are differences in asymmetry of volatility shocks and effects of control variables. In that respect, our results do not reject that volatility in the CEE economies has country-specific features (Kočenda and Valachy 2006).

4.2. Determinants of the Business Cycle

We estimate Equation (3) with the general method of moments (GMM) estimator. Comparing with OLS or IV estimators, the GMM method is preferred for better dealing with problems of simultaneity bias, reverse causality, and omitted variable bias, as well as for obtaining estimates of dummy coefficients (Caporale et al. 2011). Table 5 presents the results for the baseline model of cyclical components of real output.

Table 5.

Regression results for cyclical components of output (baseline model).

For all countries, coefficients on the lagged dependent variable are significant at the 1% level. Inertia of cyclical developments in output is stronger in Hungary and Romania. These two countries are characterized by the lowest correlation with the business cycle of the Eurozone as well. Correlation between national and European business cycles is the strongest in the Czech Republic.

According to the estimates of the baseline model, exchange rate volatility is associated with the risk of recession only in Hungary. An opposite effect is obtained for the Czech Republic. Exchange rate volatility is neutral in respect to the cyclical output developments in Poland and Romania. Such findings can be considered as evidence in favor of the exchange rate disconnect. However, neutrality of output fluctuations in respect to exchange rate volatility does not mean the same lack of reaction to currency misalignment. Exchange rate undervaluation has favorable growth effects in Poland. Assuming that there is exchange rate depreciation in response to such real shock as an increase in the foreign interest rate (Table 3 and Table 4), it helps to stabilize the economy. Under such architecture of the exchange rate effects, a switch to free or managed floating looks like a reasonable exchange rate policy. In a wider context, our results imply that the Czech Republic and especially Poland both benefit from exchange rate flexibility and thus may not be interested in joining the Eurozone. However, such benefits are visible for Hungary, as the exchange rate volatility seems to be destabilizing. Among numerous explanations of the inverse relationship between exchange rate volatility and output, several ones are worth attention in the case of Hungary, such as higher risk premium, greater uncertainty about export revenues, higher risk for domestic and foreign direct investment, and adverse effect of credit constraints on domestic investments. Additionally, it is not ruled out that in a country with relatively low levels of financial development (real) exchange rate uncertainty exacerbates the negative investment effects of domestic credit market constraints (Aghion et al. 2009) or reflect disincentives for firms in creating jobs (Belke and Setzer 2003).

There is no evidence of any favorable stabilization effects of economic freedom. A negative effect is the strongest for the Czech Republic, followed by Poland and Hungary. For Romania, a negative coefficient of heritt is insignificant. It is likely that our findings reflect an excessive level of economic liberalization attained during the period of negotiations with the European Union on the terms of EU accession. While the level of economic freedom is negatively correlated with cyclical fluctuations in output, changes in the level of economic freedom are neutral in respect to yct.

Trade deficit is still an important factor behind economic growth in Hungary, Romania, and Poland (to lesser extent). Our results mean that economic recovery depends more on imports, not exports. In this context, traditional supply-side trade channels, as capital accumulation, modernization of industrial structure, and technological and institutional progress, seem to be relevant. As can be seen in the example of the Czech Republic and Poland, statistical significance of the coefficient on tradet−1 depends on the choice of the exchange rate variability.

The stimulating effect of the EU accession is the strongest in the Czech Republic, followed by Hungary. For Poland, the coefficient of EUt is much smaller and statistically significant at the 10% level only in specification with . No evidence of any EU accession effects is found for Romania.

After controlling for fiscal and monetary policies (Table 6 and Table 7), there are no changes in the assessment of exchange rate effects for Poland and Romania. For the Czech Republic, effects of exchange rate volatility on yct are confirmed but the same favorable effect of the RER undervaluation emerges in the specification with the money supply. Similar stimulating effect of the RER undervaluation is found for Hungary, although only in specification with . It is confirmed that exchange rate volatility contributes to a recession in Hungary.

Table 6.

Regression results for cyclical components of output (extended model-I).

Table 7.

Regression results for cyclical components of output (extended model-II).

A negative link between economic freedom (in levels) and business cycle is very robust for the Czech Republic, while the estimates for other countries are specification dependent. For Hungary, economic freedom becomes neutral in respect to cyclical developments in output in 3 out of 4 specifications. It is just the opposite for Romania, where a statistically significant negative link between heritt and yct emerges in specifications with both moneyct and rcbt. Additionally, Romania emerges as the only CEE country with a statistically significant positive effect of an increase in economic freedom (in first differences) on output. For Poland, a negative relationship between heritt and yct disappears in specification with moneyct, while being strengthened in the specification with rcbt.

An excessive money supply, moneyct, helps to stabilize output in the Czech Republic and Poland. Assuming a link between the money supply and exchange rate volatility (Devereux and Engel 2002), it only strengthens the assumption of shock-absorbing properties of the floating exchange rate regimes for the Czech koruna and Polish zloty.

An increase in the central bank reference rate acts in the expected countercyclical manner in Hungary, while counterintuitive proportional link between rcbt and yct is observed in Poland. It is possible to hypothesize that such an outcome results from efforts by the central bank to avoid appreciation of the exchange rate. As a higher central bank rate can tap capital inflows, sterilization policies substitute a stronger currency with a higher excessive money supply that ultimately becomes responsible for an increase in output. For Romania, it is likely that the lack of sensitivity to the central bank policy rate is explained by the balance sheet effect, as argued by Georgiadis and Zhu (2019).

For the Czech Republic and Romania, there is evidence of stabilization properties of the fiscal tightening. The so-called non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy mean that in the case of recession it is necessary to improve the budget balance, not engage in rounds of fiscal stimuli, as has been the case in many industrial countries since the world financial crisis of 2008–2009.

When the extended dataset is used (using both fiscal and monetary variables), there are several changes to the assessment of trade and EU accession output effects. A negative link between tradet−1 and yct is confirmed for Hungary and it becomes more stable for the Czech Republic. As for Poland and Romania, a negative impact of the trade balance is observed in specifications with moneyct, but the effect is lost in specifications with rcbt. A strong procyclical effect of entering the EU is confirmed for the Czech Republic and Hungary. For Poland, a stimulating effect of similar amplitude emerges in the specification with rcbt, although it is not observed in the specification with moneyct.

5. Robustness Check

As suggested by Rodrik (2008), we use the measure of currency misalignment based on the RER adjusted for the level of output. This measure adjusts the relative price of tradables to nontradables for the fact that the relative prices of nontradables tend to rise in line with the higher level of output. Our estimates support the assumption of the RER appreciation for the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Romania (Table 8). However, no link between the level of output and RER is found for Poland.

Table 8.

Estimates of the RER adjusted for the level of output.

Estimates of the determinants of cyclical components of output are presented in Table 9 and Table 10. With the use of the measure of currency misalignment based on the RER adjusted for the level of output, rerpppct, the architecture of main relationships between exchange rate developments and cyclical changes in output is confirmed. First, exchange rate volatility is a stabilizing factor in the Czech Republic, with an opposite effect in Hungary. For Romania, exchange rate volatility is neutral in respect to the business cycle. As for Poland, a possibility of stimulating effect is offered by specification with and rcbt, but it is not confirmed by the estimates of other specifications.

Table 9.

Regression results for cyclical components of output (extended model-I).

Table 10.

Regression results for cyclical components of output (extended model-II).

Second, cyclical output effects of currency misalignment are quite similar. Regardless of specifications of regression model or indicators of currency misalignment used, it is confirmed that undervaluation of the Polish zloty has a stimulating effect on output. As argued by Rodrik (2008), such an outcome can be explained by the size of the tradable sector (especially industry); however, it is less convincing that undervaluation is aimed at compensating for the institutional weakness and the market failures (information and coordination externalities). Undervaluation of the Czech koruna brings about stabilization effects only in the specification with moneyct. The case is similar with the Hungarian forint, but in this case a positive coefficient on rerpppct becomes insignificant in the specification with .

Higher levels of economic freedom unambiguously destabilize output for the Czech Republic and Romania. However, changes in the level of economic freedom have an opposite effect in the latter, quite similar to the estimates with rerct (Table 7). For Hungary, a negative link between heritt and yct becomes statistically significant in the specification with moneyct. Estimates for Poland do not reveal any differences in respect to output effects of economic freedom.

Using rerpppct instead of rerct significantly improves assessment of output effects by the EU accession for Poland. An opposite outcome is found for Hungary in specification with rcbt. If measure currency misalignment by rerpppct, a negative link between tradet−1 and yct becomes somewhat stronger in specifications with moneyct.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the determinants of exchange rate volatility and its impact on the cyclical changes in output for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania (all of which support a floating exchange rate regime of their currencies). Using quarterly data for the 2000–2019 period, exchange rate volatility was estimated with the EGARCH(1,1) model. As indicated by the ARCH term, the impact of “surprises” from previous periods is the strongest in the Czech Republic and Poland, with a much weaker effect in Hungary and Romania. Based on the value of the EGARCH term, persistence of exchange rate volatility was observed at the statistically significant level in the Czech Republic and Hungary (extended model). For the Czech Republic and Romania, it was found that negative news affects the volatility more heavily than positive news. It is just the opposite in Hungary. Among the control variables, inflation contributes to exchange rate volatility in Romania, while an opposite relationship was found for the Czech Republic and Hungary. There was no difference between all four CEE countries in that crisis developments are associated with higher exchange rate volatility. As suggested by the estimated coefficients on sub-indices of economic freedom, exchange rate volatility becomes lower in a more liberal environment.

The empirical results using GMM estimation technique suggest that exchange rate volatility reduces the risk of recession in the Czech Republic while the opposite effect is found for Hungary and Romania, with a neutrality for Poland. These findings continue to hold after controlling for the fiscal and monetary policy indicators. Ultimately, there is support for an assumption of heterogeneous growth effects of exchange rate volatility across countries. There is evidence that the RER undervaluation prevents sliding into a recession on a credible basis in Poland only (the result is very robust to changes in the specification of regression model), with a neutral stance for other countries. There is no evidence of any favorable stabilization effects of economic freedom. Except in Romania, higher level of economic freedom is associated with worsening of the cyclical position of output. Among other results, stabilization policies in the recession imply fiscal tightening for the Czech Republic and Romania, higher money supply for the Czech Republic and Poland, and lower central bank reference rate for Hungary.

Our research helps to understand potential constrains of exchange rate flexibility as an output stabilization tool in terms of both exchange rate volatility and currency misalignment. However, further research is needed in order to explain significant differences in the output effects of exchange rate volatility across CEE countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S.; methodology, V.S.; software, R.K.; validation, V.S.; formal analysis, V.S.; investigation, R.K.; resources, R.K.; data curation, R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.; writing—review and editing, V.S.; visualization, R.K.; supervision, V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aghion, Philippe, Philippe Bacchetta, Romain Ranciere, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2009. Exchange Rate Volatility and Productivity Growth: The Role of Financial Development. Journal of Monetary Economics 56: 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Shaghil, Christofer Gust, Steven B. Kamin, and Jonathan Huntley. 2002. Are Depreciations as Contractionary as Devaluations? A Comparison of Selected Emerging and Industrial Economies. FRB International Finance Discussion Paper No. 737. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar]

- Aizenman, Joshua, Yothin Jinjarak, Gemma Estrada, and Shu Tian. 2018. Flexibility of adjustment to shocks: Economic growth and volatility of middle-income countries before and after the global financial crisis of 2008. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54: 1112–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, Nikolaos, and Julia Darby. 2012. Forecasting Volatility in Developing Countries’ Nominal Exchange Returns. MPRA Paper No. 40875. Munich: University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Arratibel, Olga, Davide Furceri, Reiner Martin, and Aleksandra Zdzienicka-Durand. 2011. The Effect of Nominal Exchange Rate Volatility on Real Macroeconomic Performance in the CEE Countries. Economic Systems 35: 261–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azid, Toseef, Muhammad Jamil, and Aneela Kousar. 2005. Impact of Exchange Rate Volatility on Growth and Economic Performance: A Case Study of Pakistan, 1973–2003. Pakistan Development Review 44: 749–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, Philippe, and Eric van Wincoop. 2013. On the unstable relationship between exchange rates and macroeconomic fundamentals. Journal of International Economics 91: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barguellil, Achouak, Ousama Ben-Salha, and Mourad Zmami. 2018. Exchange Rate Volatility and Economic Growth. Journal of Economic Integration 33: 1302–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belke, Ansgar, and Ralph Setzer. 2003. Exchange Rate Volatility and Employment Growth: Empirical Evidence from the CEE Economies. CESifo Working Paper No. 1056. Munich: Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo). [Google Scholar]

- Benhima, Kenza. 2012. Exchange Rate Volatility and Productivity Growth: The Role of Original Sin. Open Economies Review 23: 501–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béreau, Sophie, Antonia Lopez-Villavicencio, and Valerie Mignon. 2012. Currency Misalignments and Growth: A New Look using Nonlinear Panel Data Methods. Applied Economics 44: 3503–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, Christian. 2016. Economic freedom and economic crises. European Journal of Political Economy 45: 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleaney, Michael, and Manuela Francisco. 2010. What Makes Currencies Volatile? An Empirical Investigation. Open Economies Review 21: 731–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleaney, Michael, and David Greenaway. 2001. The impact of terms of trade and real exchange rate volatility on investment and growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development Economics 65: 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boar, Corina Georgeta. 2010. Exchange rate volatility and growth in emerging Europe. The Review of Finance and Banking 2: 103–20. [Google Scholar]

- Borys, Magdalena, Éva Polgár, and Andrei Zlate. 2008. Real Convergence and the Determinants of Growth in EU Candidate and Potential Candidate Countries—A Panel Data Approach. ECB Occasional Paper No. 86. Frankfurt: European Central Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, Ricardo J., and Guido Lorenzoni. 2014. Persistent Appreciations and Overshooting: A Normative Analysis. IMF Economic Review 62: 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, César, and Megumi Kubota. 2018. Does Higher Openness Cause More Real Exchange Rate Volatility? Journal of International Economics 110: 176–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, Guglielmo, Thouraya Amor, and Christophe Rault. 2011. Sources of Real Exchange Rate Volatility and International Financial Integration: A Dynamic GMM Panel Approach. CESifo Working Paper No. 3645. Munich: Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo). [Google Scholar]

- Corsetti, Giancarlo. 2006. Openness and the case for flexible exchange rates. Research in Economics 60: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Corsetti, Giancarlo, Keith Kuester, and Gernot J. Müller. 2017. Fixed on Flexible Rethinking Exchange Rate Regimes after the Great Recession. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics No. 1729. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. Available online: http://www.econ.cam.ac.uk/research-files/repec/cam/pdf/cwpe1729.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Cuestas, Juan Carlos, Mercedes Monfort, and Javier Ordóñez. 2019. Real Exchange Rates and Competitiveness in Central and Eastern Europe: Have They Fundamentally Changed? Working Papers 2019/12. Castellón: Universitat Jaume I. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, Jacob, and Jan-Egbert Sturm. 2000. On the Relationship Between Economic Freedom and Economic Growth. European Journal of Political Economy 16: 215–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, Jacob, Susanna Lundström, and Jan-Egbert Sturm. 2006. Market oriented institutions and policies and economic growth: A critical survey. Journal of Economic Surveys 20: 157–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Firat. 2013. Growth under exchange rate volatility: Does access to foreign or domestic equity markets matter? Journal of Development Economics 100: 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Michael B., and Charles Engel. 2002. Exchange rate pass-through, exchange rate volatility, and exchange rate disconnect. Journal of Monetary Economics 49: 913–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Michael B., and Philip R. Lane. 2003. Understanding bilateral exchange rate volatility. Journal of International Economics 60: 109–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, David. 1992. Outward-oriented developing economies really do grow more rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976–1985. Economic Development and Cultural Change 40: 523–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornbusch, Rudiger. 2001. Fewer Monies, Better Monies. NBER Working Papers No. 8324. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch, Rudiger, and Alberto Giovannini. 1990. Monetary Policy in the Open Economy. In Handbook of Monetary Economics. Edited by Benjamin M. Friedman and Frank H. Hahn. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publisher, vol. 2, pp. 1231–303. [Google Scholar]

- Doucouliagos, Chris, and Mehmet Ali Ulubasoglu. 2006. Economic freedom and economic growth: Does specification make a difference? European Journal of Political Economy 22: 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlauf, Steven N. 2018. Institutions, Development and Growth: Where Does Evidence Stand? EDI Working Paper Series, 18/04.1; Oxford: Economic Development & Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Sebastian. 2011. Exchange-Rate Policies in Emerging Countries: Eleven Empirical Regularities from Latin America and East Asia. Open Economies Review 22: 533–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Sebastian, and Eduardo Levy-Yeyati. 2005. Flexible exchange rates as shock absorbers. European Economic Review 49: 2079–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, Stefan, and Helge C. Littke. 2017. Central Bank Transparency and the Volatility of Exchange Rates. IWH Discussion Papers, 22/2017. Halle: Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Halle (IWH). Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:3:2-80759 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Emara, Noha, and Loreto Reyes. 2020. Economic Freedom and Economic Performance: Does Good Governance Matter? The Case of APAC and OECD Countries. MPRA Paper, No. 103590. Munich: University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, Charles. 2011. Currency misalignments and optimal monetary policy: A reexamination. American Economic Review 101: 2796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdmuc, Jarko, and Roman Horváth. 2007. Volatility of Exchange Rates in Selected New EU Members: Evidence from Daily Data. CESifo Working Paper, No. 2107. Munich: Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo). [Google Scholar]

- Fratzscher, Marcel, Dagfinn Rime, Lucio Sarno, and Gabriele Zinna. 2015. The scapegoat theory of exchange rates: The first tests. Journal of Monetary Economics 70: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, Jacob A., and Morris Goldstein. 1991. Exchange Rate Volatility and Misalignment: Evaluating Some Proposals for Reform. In Evolution of the International and Regional Monetary Systems. Edited by Alfred Steinherr and Daniel Weiserbs. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 185–220. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, Michael, Christian Pierdzioch, and Georg Stadtmann. 2005. The effects of Japanese foreign exchange market interventions on the yen/U.S. dollar exchange rate volatility. International Review of Economics & Finance 14: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furceri, Davide, and Aleksandra Zdzienicka. 2012. How costly are debt crises? Journal of International Money and Finance 31: 726–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, Georgios, and Feng Zhu. 2019. Monetary Policy Spillovers, Capital Controls and Exchange Rate Flexibility, and the Financial Channel of Exchange Rates. ECB Working Paper Series; Frankfurt: European Central Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Atish, Anne-Marie Gulde, and Holger Wolf. 2003. Exchange Rate Regimes: Choices and Consequences. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giannellis, Nikolaos, and Athanasios Papadopoulos. 2011. What causes exchange rate volatility? Evidence from selected EMU members and candidates for EMU membership countries. Journal of International Money and Finance 30: 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Mona, and Cosimo Pancaro. 2010. Can Real Exchange Rate Undervaluation Boost Exports and Growth in Developing Countries? Yes, But Not for Long. In Economic Premise. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/10178 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Han, Yujing. 2020. The impact of exchange rate fluctuation on economic growth—Empirical studies based on different countries. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 146: 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hau, Harald. 2002. Real exchange rate volatility and economic openness: Theory and evidence. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 34: 611–30. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3270734 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Hausmann, Ricardo, Lan Pritchett, and Dani Rodrik. 2005. Growth Accelerations. Journal of Economic Growth 10: 303–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, Márcio, Flávio Vieira, Cleomar Gomes da Silva, and Luiz Carlos Bottecchia. 2013. Growth and exchange rate volatility: A panel data analysis. Applied Economics 45: 3733–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, Muhammad, Erich W. Streissler, and Robert M. Kunst. 2012. Exchange rate volatility and its impact on industrial production, before and after the introduction of common currency in Europe. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 2: 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Janus, Thorste, and Daniel Riera-Crichton. 2015. Real exchange rate volatility, economic growth and the euro. Journal of Economic Integration 30: 148–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhro, Solikin M., and Dinh Hoang Bach Phan. 2018. Can economic policy uncertainty predict exchange rate and its volatility? Evidence from ASEAN countries. Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking 21: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justesen, Mogens K. 2008. The effect of economic freedom on growth revisited: New evidence on causality from a panel of countries 1970–1999. European Journal of Political Economy 24: 642–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadam, Duygu Yolcu, and Erdal Ozmen. 2016. Real Exchange Rates and Growth. ERC Working Papers, No. 1609. Ankara: Middle East Technical University. [Google Scholar]

- Kočenda, Evzen, and Juraj Valachy. 2006. Exchange Rate Volatility and Regime Change: Visegrad Comparison. IPC Working Paper Series, No. 7; Ann Abror: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, Paul. 1988. Deindustrialization, Reindustrialization, and the Real Exchange Rate. NBER Working Papers, No. 2586. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lyócsa, Štefan, Peter Molnár, and Igor Fedorko. 2016. Forecasting Exchange Rate Volatility: The Case of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland. Czech Journal of Economics and Finance 66: 453–75. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, Ronald, and Flávio Vieira. 2010. A Panel Data Investigation of Real Exchange Rate Misalignment and Growth. CESifo Working Paper, No. 3061. Munich: Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo). [Google Scholar]

- McAleer, Michael, and Christian M. Hafner. 2014. A one line derivation of EGARCH. Econometrics 2: 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, Ronald. 1963. Optimum Currency Areas. The American Economic Review 53: 717–25. [Google Scholar]

- Miletić, Siniša. 2015. Modeling exchange rate volatility in CEEC countries: Impact of global financial and European sovereign debt crisis. Megatrend Review 12: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, Fatbardha, Eglantina Hysa, Uğur Ergün, Mirela Panait, and Marian Voica. 2020. The effect of exchange rate volatility on economic growth: Case of the CEE countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvillier, Florian. 2020. Do currency undervaluations affect the impact of inflation on growth? Economic Modelling 84: 275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, Michael. 1986. Nominal exchange rate regimes and the behaviour of real exchange rates: Evidence and implications. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 25: 117–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newey, Whithney K., and Kenneth D. West. 1994. Automatic Lag Selection in Covariance Matrix Estimation. The Review of Economic Studies 61: 631–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff. 1995. Exchange Rate Dynamics Redux. The Journal of Political Economy 103: 624–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadamou, Stephanos, Moïse Sidiropoulos, and Eleftherios Spyromitros. 2016. Central bank transparency and exchange rate volatility effects on inflation-output volatility. Economics and Business Letters 5: 25–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracchi, Cosimo. 2021. The Mussa Puzzle: A Generalization. BU Working Papers, 2021-001. Providence: Brown University. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Thi Hong Hanh. 2018. Liquidity and Exchange Rate Volatility. LEMNA Working Paper, EA 4272. Nantes: University of Nantes. [Google Scholar]

- Ribero, Rafael S. M., John S. L. McCombie, and Gilbeto Tadeu Lima. 2020. Does real exchange undervaluation really promote economic growth? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 52: 408–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, Dani. 2008. The real exchange rate and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 39: 365–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabl, Gunther. 2009. Exchange rate volatility and growth in emerging Europe and East Asia. Open Economies Review 20: 565–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, Roland, and Ivan Tchakarov. 2004. Non-Fundamental Exchange Rate Volatility and Welfare. ECB Working Paper Series, 328; Frakfurt: European Central Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Tsangarides, Charalambos G. 2012. Crisis and recovery: Role of the exchange rate regime in emerging market economies. Journal of Macroeconomics 34: 470–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzelac, Ozren, Milivoje Davidovic, and Marijana Dukic Mijatovic. 2020. Milivoje Davidovic, and Marijana Dukic Mijatovic. 2020. Legal Framework, Political Environment and Economic Freedom in Central and Eastern Europe: Do They Matter for Economic Growth? Post-Communist Economies 32: 697–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Christoph S. 2017. The Effect of Central Bank Transparency on Exchange Rate Volatility. BGPE Discussion Paper, 174. Nürnberg: Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).