Household’s Overindebtedness during the COVID-19 Crisis: The Role of Debt and Financial Literacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Overview

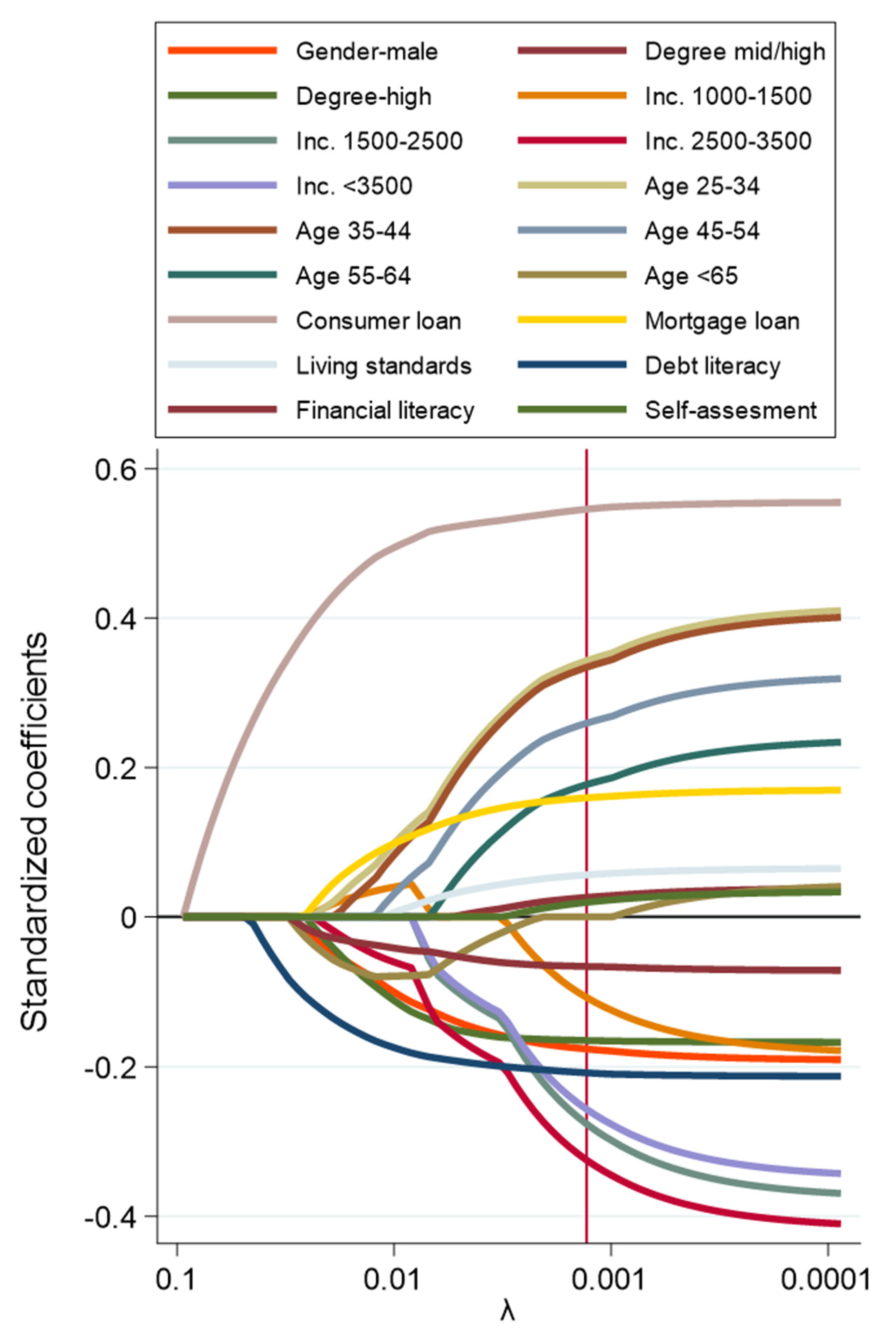

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Possible Answers |

|---|---|

| Financial Literacy I (FL I): Suppose you had PLN100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow? | (a) More than 102 PLN; (b) Exactly 102 PLN; (c) Less than 102 PLN; |

| Financial Literacy II (FL II): Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, how much would you be able to buy with the money in this account? | (a) More than today; (b) Exactly the same; (c) Less than today; |

| Financial Literacy III (FL III): Please tell me whether this statement is true or false. “Buying a single company’s stock usually provides a safer return than a stock mutual fund”. | (a) True; (b) False; |

| Debt literacy I (DL I): Suppose you owe PLN1000 on your credit card and the interest rate you are charged is 20% per year compounded annually. If you didn’t pay anything off, at this interest rate, how many years would it take for the amount you owe to double? | (a) 2 years; (b) Less than 5 years; (c) 5 to 10 years; (d) More than 10 years; (e) Do not know; |

| Debt literacy II (DL II): You owe PLN3000 on your credit card. You pay a minimum payment of PLN30 each month. At an annual percentage rate of 12% (or 1% per month), how many years would it take to eliminate your credit card debt if you made no additional new charges? | (a) Less than 5 years; (b) Between 5 and 10 years; (c) Between 10 and 15 years; (d) Never, you will continue to be in debt; (e) Do not know; |

| Debt literacy III (DL III): You purchase an appliance which costs PLN1000. To pay for this appliance, you are given the following two options: (a) Pay 12 monthly installments of PLN100 each; (b) Borrow at a 20% annual interest rate and pay back PLN1200 a year from now. Which is the more advantageous offer? | (a) Option (a); (b) Option (b); (c) They are the same; (d) Do not know; |

| Debt literacy IV (DL IV)—country specific question: Let’s assume you want to buy a car. You decide to borrow funds to buy this car. What do you think, the offer of which institution will be the least advantageous for you: | (a) Commercial bank; (b) Shadow bank institution; (c) Credit union; (d) Cooperative bank; |

| Indebtedness question: Which of the following best describes your current debt position? | (a) I have too much debt right now and I have difficulty paying it off. (b) I am currently paying off my debt regularly. (c) I have no debt at the moment. |

| Variable | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 642 | |

| Female | 658 | |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 180 | |

| 25–34 | 339 | |

| 35–44 | 314 | |

| 45–54 | 197 | |

| 55–64 | 168 | |

| Age > 64 | 102 | |

| Degree | ||

| Elementary | 130 | |

| Middle-high | 628 | |

| High | 542 | |

| Income (PLN) | ||

| Income < 1000 | 80 | |

| 1000–1500 | 190 | |

| 1500–2499 | 440 | |

| 2500–3500 | 311 | |

| Income > 3500 | 279 | |

| Variable | FL I | FL II | FL III | DL I | DL II | DL III | DL IV | Self-Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 75.7% | 72.4% | 75.9% | 48.4% | 25.1% | 14.8% | 56.7% | 4.2 | |

| Female | 68.7% | 54.1% | 61.6% | 39.1% | 15.7% | 14.3% | 49.8% | 3.98 | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–24 | 73.9% | 57.2% | 57.8% | 43.9% | 21.7% | 13.3% | 59.4% | 4.04 | |

| 25–34 | 54.9% | 65.8% | 51.6% | 42.2% | 20.4% | 17.1% | 54.9% | 4.1 | |

| 35–44 | 71.7% | 62.1% | 71.7% | 43.0% | 18.2% | 15.0% | 54.8% | 4.15 | |

| 45–54 | 74.6% | 75.1% | 76.6% | 45.7% | 22.3% | 16.8% | 49.2% | 4.12 | |

| 55–64 | 78.0% | 73.8% | 79.8% | 45.8% | 26.8% | 10.7% | 51.2% | 4.05 | |

| Age > 64 | 77.5% | 74.5% | 79.4% | 43.1% | 17.6% | 8.8% | 43.1% | 3.98 | |

| Degree | |||||||||

| Elementary | 66.2% | 50.8% | 59.2% | 33.8% | 5.4% | 12.3% | 38.5% | 3.7 | |

| Middle-high | 71.2% | 61.1% | 67.7% | 42.0% | 19.9% | 12.9% | 52.1% | 4 | |

| High | 74.7% | 68.5% | 72.0% | 48.0% | 25.8% | 17.0% | 58.1% | 4.29 | |

| Variable | Mortgage Loan | Car Loan | Loan for Household Goods | Current Account Loan | Credit Card Loan | Cash Loan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 23.1% | 17.3% | 36.1% | 17.1% | 28.7% | 38.2% | |

| Female | 16.9% | 15.0% | 30.1% | 13.1% | 22.0% | 34.3% | |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–24 | 15.0% | 11.7% | 15.0% | 7.2% | 12.8% | 18.3% | |

| 25–34 | 19.5% | 15.6% | 32.7% | 10.9% | 19.2% | 39.8% | |

| 35–44 | 30.6% | 15.9% | 37.6% | 11.8% | 24.8% | 35.0% | |

| 45–54 | 19.3% | 21.8% | 38.1% | 26.4% | 37.6% | 44.2% | |

| 55–64 | 14.9% | 17.9% | 36.9% | 21.4% | 33.3% | 37.5% | |

| Age > 64 | 6.9% | 12.7% | 36.3% | 20.6% | 32.4% | 42.2% | |

| Degree | |||||||

| Elementary | 10.8% | 8.5% | 31.5% | 12.3% | 13.8% | 31.5% | |

| Middle-high | 15.4% | 13.2% | 31.8% | 12.7% | 22.9% | 39.5% | |

| High | 27.3% | 21.4% | 34.9% | 18.5% | 30.8% | 33.6% | |

| Variable | Average Level of Living Standards (in PLN) | Average Level of Savings in Months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3653.33 | 9.30 | |

| Female | 3709.37 | 6.08 | |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 3481.99 | 7.05 | |

| 25–34 | 3607.65 | 6.92 | |

| 35–44 | 3867.18 | 7.61 | |

| 45–54 | 3799.99 | 8.35 | |

| 55–64 | 3592.76 | 7.86 | |

| Age > 64 | 3618.40 | 6.12 | |

| Degree | |||

| Elementary | 3296.58 | 5.45 | |

| Middle-high | 3628.80 | 6.89 | |

| High | 3837.10 | 8.68 | |

| Variable | Currently Overindebt | Currently Have No Problems with Debt Repayment | Have No Debt | Possibly Overindebt during COVID-19 Crisis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 8.52% | 49.09% | 42.39% | 9.27% | |

| Female | 10.28% | 42.83% | 46.89% | 12.94% | |

| Age | |||||

| 18–24 | 6.11% | 27.22% | 66.67% | 6.11% | |

| 25–34 | 8.55% | 48.97% | 42.48% | 15.34% | |

| 35–44 | 7.64% | 54.46% | 37.90% | 14.01% | |

| 45–54 | 12.18% | 52.28% | 35.54% | 12.18% | |

| 55–64 | 14.88% | 38.69% | 46.43% | 4.76% | |

| Age > 64 | 8.82% | 43.14% | 48.04% | 4.90% | |

| Degree | |||||

| Elementary | 15.38% | 40.00% | 44.62% | 9.23% | |

| Middle-high | 10.99% | 44.43% | 44.58% | 11.94% | |

| High | 6.09% | 49.26% | 44.65% | 10.52% | |

| Reference Variable | Variables | Overindebt | Possibly Overindebt (COVID-19) | Overindebt | Possibly Overindebt (COVID-19) | Overindebt | Possibly Overindebt (COVID-19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Gender (male) | −0.2785 (0.228) | −0.3884 * (0.025) | −0.2718 (0.238) | −0.4504 ** (0.009) | −0.3441 (0.134) | −0.4443 ** (0.010) |

| Elementary | Middle-high | −0.0073 (0.982) | 0.2106 (0.496) | −0.0757 (0.816) | 0.1171 (0.704) | −0.1374 (0.672) | 0.1220 (0.691) |

| High | −0.6596 (0.075) | −0.0834 (0.796) | −0.7248 * (0.046) | −0.2256 (0.480) | −0.8427 * (0.020) | −0.2238 (0.480) | |

| Income < 1000 | Income 1000–1500 | −0.4979 (0.214) | −0.3643 (0.322) | −0.4822 (0.232) | −0.3887 (0.289) | −0.5020 (0.211) | −0.4133 (0.263) |

| Income 1500–2500 | −1.2771 *** (0.001) | −0.4744 (0.163) | −1.2393 *** (0.001) | −0.5088 (0.134) | −1.2852 *** (0.001) | −0.5241 (0.124) | |

| Income 2500–3500 | −1.1209 ** (0.006) | −0.8013 * (0.025) | −1.0855 ** (0.008) | −0.8336 * (0.020) | −1.1255 ** (0.006) | −0.8498 * (0.018) | |

| Income > 3500 | −1.0077 * (0.017) | −0.5965 (0.100) | −0.9677 * (0.022) | −0.6137 (0.090) | −0.9774 * (0.021) | −0.6451 (0.078) | |

| Age 18–24 | Age 25–34 | 0.6191 (0.119) | 1.1125 *** (0.000) | 0.56648 (0.156) | 1.1393 *** (0.000) | 0.6569 (0.097) | 1.1375 *** (0.000) |

| Age 35–44 | 0.5230 (0.207) | 1.0884 *** (0.001) | 0.5799 (0.161) | 1.1335 *** (0.000) | 0.5998 (0.147) | 1.1388 *** (0.000) | |

| Age 45–54 | 0.8510 * (0.046) | 0.8567 * (0.014) | 0.9840 * (0.021) | 0.8761 * (0.012) | 0.9009 * (0.034) | 0.8902 ** (0.010) | |

| Age 55–65 | 1.0295 * (0.012) | 0.3090 (0.413) | 1.2075 ** (0.004) | 0.3129 (0.408) | 1.0598 ** (0.010) | 0.3389 (0.368) | |

| Concumer loan experience | 1.5186 *** (0.000) | 1.0667 *** (0.000) | 1.4999 *** (0.000) | 1.0493 *** (0.000) | 1.4986 *** (0.000) | 1.0427 *** (0.000) | |

| Mortgage loan experience | −0.0297 (0.342) | 0.6749 *** (0.000) | −0.3725 (0.233) | 0.6360 *** (0.000) | −0.0332 (0.285) | 0.6240 *** (0.001) | |

| Living standards | −0.0002 ** (0.007) | 0.0001 ** (0.006) | −0.0002 * (0.019) | 0.0001 ** (0.008) | −0.0002 ** (0.007) | 0.0001 ** (0.008) | |

| Debt Literacy | −1.1981 ** (0.010) | −0.8120 * (0.018) | |||||

| Financial literacy | −1.0176 ** (0.002) | 0.07252 (0.771) | |||||

| Self-assessment | −0.0516 (0.484) | 0.0439 (0.452) | |||||

| constans | −1.4113 ** (0.010) | −2.7366 *** (0.000) | −1.2523 * (0.025) | −2.8747 *** (0.000) | −1.4293 * (0.014) | −2.9922 *** (0.000) | |

| Sample | 1198 | 1198 | 1198 | 1198 | 1198 | 1198 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0973 | 0.0972 | 0.0921 | ||||

References

- Agnew, Julie R., Hazel Bateman, and Susan Thorp. 2013. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Australia. Numeracy 6: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessie, Rob, Maarten Van Rooij, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2011. Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 10.4: 527. [Google Scholar]

- Almenberg, Johan, and Jenny Säve-Söderbergh. 2011. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 585–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Morris. 2012. Implications of behavioural economics for financial literacy and public policy. The Journal of Socio-Economics 41: 677–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondel, Luc, Majdi Debbich, and Frédérique Savignac. 2013. Financial Literacy and Financial Planning in France. Numeracy 6: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artavanis, Nikolaos, and Soumya Karra. 2020. Financial literacy and student debt. The European Journal of Finance 26: 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi Doosti, Bahar, and Abdolhosein Karampour. 2017. The impact of behavioral factors on Propensity toward indebtedness Case Study: Indebted customers of Maskan Bank, Tehran province (Geographic regions: East). Journal of Advances in Computer Engineering and Technology 3: 145–52. [Google Scholar]

- Azma, Nurul, Mahfuzur Rahman, Adewale Abideen Adeyemi, and Muhammad Khalilur Rahman. 2019. Propensity toward indebtedness: Evidence from Malaysia. Review of Behavioral Finance 11: 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, James, Cormac o’Dea, and Zoë Oldfield. 2010. Cognitive Function, Numeracy and Retirement Saving Trajectories. The Economic Journal 120: F381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckmann, Elisabeth. 2013. Financial Literacy and Household Savings in Romania. Numeracy 6: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białowolski, Piotr, Andrzej Cwynar, Wiktor Cwynar, and Dorota Więziak-Białowolska. 2020. Consumer debt attitudes: The role of gender, debt knowledge and skills. International Journal of Consumer Studies 44: 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisclair, David, Annamaria Lusardi, and Pierre-Carl Michaud. 2017. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Canada. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 16: 277–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongini, Paola, Luca Colombo, and Malgorzata Iwanicz-Drozdowska. 2015. Financial literacy: Where do we stand? Journal of Financial Management, Markets and Institutions 3: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, Paula A., Catherine Cubbin, Susan Egerter, Sekai Chideya, Kristen S. Marchi, Marilyn Metzler, and Samuel Posner. 2005. Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. Journal of the American Medical Association 294: 2879–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Martin, and Roman Graf. 2013. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy 6.2: 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Meta, John Grigsby, Wilbert Van Der Klaauw, Jaya Wen, and Basit Zafar. 2016. Financial Education and the Debt Behavior of the Young. The Review of Financial Studies 29: 2490–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher-Koenen, Tabea, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2011. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 565–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholtz, Sonia, Jan Gąska, and Marek Góra. 2021. Myopic Savings Behaviour of Future Polish Pensioners. Risks 9: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Devlina, Mahendra Kumar, and Kapil K. Dayma. 2019. Income security, social comparisons and materialism. International Journal of Bank Marketing 37: 1041–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Haiyang, and Ronald P. Volpe. 2002. Gender Differences in Personal Financial Literacy Among College Students. Financial Services Review 11: 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Christelis, Dimitris, Tullio Jappelli, and Mario Padula. 2010. Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. European Economic Review 54: 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courchane, Marsha, and Peter Zorn. 2005. Consumer literacy and creditworthiness. Proceedings, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Conference, Promises and Pitfalls: As Consumer Options Multiply, Who Is Being Served and at What Cost? April 7, 2005 in Washington, DC. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/fipfedhpr/950.htm (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Crossan, Diana. 2011. How to Improve Financial Literacy: Some Successful Strategies. In Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and Annamaria Lusardi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 241–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cwynar, Andrzej. 2020. Financial literacy, behaviour and well-being of millennials in Poland compared to previous generations: The insights from three large-scale surveys. Review of Economic Perspectives 20: 289–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwynar, Andrzej, Wiktor Cwynar, and Przemysław Szuba. 2018. Financial education, debt literacy and credit market participation: The case of Poland. Economic Policy in the European Union Member Countries 44. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrzej-Cwynar-2/publication/332496435_FINANCIAL_EDUCATION_DEBT_LITERACY_AND_CREDIT_MARKET_PARTICIPATION_THE_CASE_OF_POLAND/links/5cbee854a6fdcc1d49a89664/FINANCIAL-EDUCATION-DEBT-LITERACY-AND-CREDIT-MARKET-PARTICIPATION-THE-CASE-OF-POLAND.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Cwynar, Andrzej, Wiktor Cwynar, and Kamil Wais. 2019. Debt literacy and debt literacy self-assessment: The case of Poland. Journal of Consumer Affairs 53: 24–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, Christian D., and Lena Jaroszek. 2013. Knowing What Not to Do: Financial Literacy and Consumer Credit Choices. Discussion Paper, No. 13-027. Mannheim: Center for European Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Lu, and Swarn Chatterjee. 2018. Application of situational stimuli for examining the effectiveness of financial education: A behavioral finance perspective. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 17: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornero, Elsa, and Chiara Monticone. 2011. Financial Literacy and Pension Plan Participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 547–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathergood, John. 2011. Self-Control, Financial Literacy and Consumer Over-Indebtedness. Journal of Economic Psychology 33: 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathergood, John, and Jörg Weber. 2017. Financial literacy, present bias and alternative mortgage products. Journal of Banking & Finance 78: 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gerardi, Kristopher, Lorenz Goette, and Stephan Meier. 2013. Numerical ability predicts mortgage default. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 11267–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, Jackie. 2012. Brothers are doing it for themselves? Men’s experiences of getting into and getting out of debt. The Journal of Socio-Economics 41: 327–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, Justine, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2020. How financial literacy and impatience shape retirement wealth and investment behaviors. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 19: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, Justine, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Eric Chyn. 2011. Fees, Framing, and Financial Literacy in the Choice of Pension Managers. In Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and Lusardi Annamaria. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, Sandra J. 2012. Financial literacy and the cost of borrowing. International Journal of Consumer Studies 36: 566–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmi, Panu, and Olli-Pekka Ruuskanen. 2017. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 17: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keese, Matthias. 2012. Who feels constrained by high debt burdens? Subjective vs. objective measures of household debt. Journal of Economic Psychology 33: 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hugh Hoikwang, Raimond Maurer, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2013. Time Is Money: Life Cycle Rational Inertia and Delegation of Investment Management. NBER Working Paper, No. 19732. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper, Leora F., and Georgios A. Panos. 2011. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning: The Russian Case. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Geng. 2018. Gender-Related Differences in Credit Use and Credit Scores. FEDS Notes. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Liqiong, Mohamad Dian Revindo, Christopher Gan, and David A. Cohen. 2019. Determinants of credit card spending and debt of Chinese consumers. International Journal of Bank Marketing 37: 545–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Peter Tufano. 2015. Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences, and Overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 14: 332–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyll, Tobias, and Thomas Pauls. 2019. The gender gap in over-indebtedness. Finance Research Letters 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Olivia S., and Annamaria Lusardi. 2015. Financial literacy and economic outcomes: Evidence and policy implications. Journal of Retirement 3: 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Danna L. 2003. Survey of Financial Literacy in Washington State: Knowledge, Behavior, Attitudes, and Experiences. Technical Report n. 03-39. Pullman: Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, Washington State University. [Google Scholar]

- Moure, Natalia Garabato. 2015. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Chile. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 15: 203–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Linh, Gerry Gallery, and Cameron Newton. 2019. The joint influence of financial risk perception and risk tolerance on individual investment decision-making. Accounting & Finance 59: 747–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, Mahfuzur, Nurul Azma, Md Masud, Abdul Kaium, and Yusof Ismail. 2020. Determinants of Indebtedness: Influence of Behavioral and Demographic Factors. International Journal of Financial Studies 8: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvall, Lisbeth. 2011. The Faces of Over-Indebtedness. Pathways into and out of Financial Problems. Växjö: Linnaeus University. [Google Scholar]

- Sekita, Shizuka. 2011. Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Japan. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 637–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, Nurdan, Fatih Temizel, and Özlem Sayılır. 2012. The effects of financial literacy on the borrowing behaviour of Turkish financial consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 36: 573–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Herbert A. 1978. Rationality as a process and as a product of thought. American Economic Review 70: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smaga, Paweł. 2013. Assessing Involvement of Central Banks in Financial Stability. Center for Financial Stability Policy Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2269265 (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Smith, James P., John J. McArdle, and Robert Willis. 2010. Financial decision making and cognition in a family context. The Economic Journal 120: F363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiecka, Beata, Yesilda Yesilda, Ercan Özen, and Simon Grima. 2000. Financial literacy: The case of Poland. Sustainability 12: 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, Robert. 1996. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 58: 267–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosi, Negin R., Elyse N. Voegeli, Ana Antolin, Laura G. Babbitt, and Drusilla K. Brown. 2020. Do financial literacy training and clarifying pay calculations reduce abuse at work? Journal of Social Issues 76: 581–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, Marco. 2016. Accounting and Finance Literacy and Self-Employment: An Exploratory Study. IE Business School—IE University 3: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij, Maarten, Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob Alessie. 2011. Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 449–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zissimopoulos, Julie M., Benjamin Karney, and Amy Rauer. 2008. Marital Histories and Economic Well-Being. MRRC Working Paper, WP2008-645. Ann Arbor: Michigan Retirement Research Center, University of Michigan, December 17. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Indebtedness (Dependent variable) | The variable may take the values 1, 2, or 3, depending on the debt situation of a given respondent. The value 1—respondents who declare that currently they have too much debt and difficulty paying it off. The value 2—respondents who may become insolvent during the COVID-19 pandemic. This group now regularly repays its debt (i.e., selected the answer “b” in indebtedness question). However, we limited this group to those respondents, who declare worries about losing their income and have a maximum of 3 months of savings (the 3-month threshold was assumed on the basis of the average time of looking for a job in Poland during the coronavirus pandemic). The value 3—respondents who are not at risk of overindebtedness (i.e., respondents, who paying off debt regularly and declare no worries about losing their income or have more than 3 months of savings). This group also includes people who currently have no debt (i.e., selected the answer “c” in indebtedness question). Descriptive statistics for indebtedness variables are presented in Table A6 in the Appendix A. |

| Demografic variables | Gender, Education, Income (per family member), Age. |

| Consumer loan experience | Variable identifying respondents who have taken consumer loans in the past (or are repaying them currently). The variable identifies experiences with high-margin credit products, potentially burdened with higher credit risk. |

| Mortgage loan experience | Variable identifying respondents who have taken housing loans in the past (or are repaying them currently). The variable identifies experiences with long-term credit, which potentially requires the ability to better manage personal finances and is associated with higher credit requirements for the consumer. |

| Living standards | Variable specifying how many funds a given respondent needs per month to meet their basic needs (e.g., purchase of food and other everyday goods, rent, gas, electricity, heating, taxes, and other fees). |

| Debt Literacy | Percentage of correct answers to debt management questions (DL I, DL II, DL III, DL IV). |

| Financial literacy | Percentage of correct answers to the Big Three financial literacy questions (FL I, FL II, FL III). |

| Self-assessment | Self-assessment of economic and financial skills on a scale of 0 (lack of knowledge) to 7 (high level of knowledge). Following Courchane and Zorn (2005), self-assessed knowledge turned out to be a significant factor affecting consumer financial behavior. |

| Country | FL I | FL II | FL III | Sample | Year | % of All Correct Answers | Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 82.40% | 78.40% | 61.80% | 1059 | 2009 | 53.20% | Bucher-Koenen and Lusardi (2011) |

| Switzerland | 79.30% | 78.40% | 73.50% | 1500 | 2011 | 50.10% | Brown and Graf (2013) |

| Netherland | 84.80% | 76.90% | 51.90% | 1665 | 2010 | 44.80% | Alessie et al. (2011) |

| Spain | 85.20% | 70% | 56.20% | 500 | 2015 | 44.80% | Trombetta (2016) |

| Australia | 83.10% | 63.90% | 54.70% | 1024 | 2012 | 42.70% | Agnew et al. (2013) |

| Canada | 77.90% | 66.18% | 59.36% | 6805 | 2012 | 42.50% | Boisclair et al. (2017) |

| Poland | 72.20% | 63.20% | 68.60% | 1300 | 2020 | 42.00% | This research |

| Finaland | 58.10% | 76.40% | 65.80% | 1477 | 2014 | 35.60% | Kalmi and Ruuskanen (2017) |

| France | 48% | 61.20% | 66.80% | 3616 | 2011 | 30.90% | Arrondel et al. (2013) |

| USA | 64.90% | 64.30% | 51.80% | 1488 | 2009 | 30.20% | Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) |

| Japan | 70.50% | 58.80% | 39.50% | 5268 | 2010 | 27.00% | Sekita (2011) |

| Italy | 40% | 59.30% | 52.20% | 3992 | 2007 | 24.90% | Fornero and Monticone (2011) |

| New Zealand | 86% | 81% | 49% | 850 | 2009 | 24.00% | Crossan (2011) |

| Sweden | 35.20% | 59.50% | 68.40% | 1302 | 2010 | 21.40% | Almenberg and Säve-Söderbergh (2011) |

| Romania | 41.30% | 31.80% | 14.70% | 1030 | 2011 | 3.80% | Beckmann (2013) |

| Russian Federation | 36.30% | 50.80% | 12.80% | 1366 | 2009 | 3.70% | Klapper and Panos (2011) |

| Chile | 47.40% | 17.70% | 40.60% | 14463 | 2009 | 7.70% | Moure (2015) |

| Reference Variable | Variables | (1) Overindebt | (2) Possibly Overindebt (COVID-19) | (3) Overindebt | (4) Possibly Overindebt (COVID-19) | (5) Overindebt | (6) Possibly Overindebt (COVID-19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Female | male | −0.3909 (0.076) | −0.3842 * (0.023) | −0.3708 (0.092) | −0.4421 ** (0.009) | −0.4495 * (0.040) | −0.4431 ** (0.008) |

| Degree Elementary | Middle-high | −0.1346 (0.661) | 0.2720 (0.362) | −0.1851 (0.541) | 0.1838 (0.535) | −0.2472 (0.413) | 0.1795 (0.544) |

| High | −0.7691 * (0.026) | −0.0646 (0.836) | −0.8128 * (0.017) | −0.1996 (0.518) | −0.9286 ** (0.006) | −0.2124 (0.489) | |

| Income < 1000 | Income 1000–1500 | −0.5350 (0.170) | −0.4667 (0.196) | −0.5272 (0.179) | −0.4906 (0.173) | −0.5326 (0.171) | −0.5222 (0.149) |

| Income 1500–2500 | −1.2620 *** (0.001) | −0.5208 (0.116) | −1.2346 *** (0.001) | −0.5549 * (0.094) | −1.2688 *** (0.001) | −0.5781 (0.082) | |

| Income 2500–3500 | −1.1031 ** (0.005) | −0.8511 * (0.015) | −1.0813 ** (0.006) | −0.8840 * (0.011) | −1.1077 ** (0.005) | −0.9087 ** (0.010) | |

| Income > 3500 | −1.0400 ** (0.010) | −0.6942 * (0.050) | −1.0335 * (0.011) | −0.7170 * (0.043) | −1.0164 * (0.012) | −0.7604 * (0.033) | |

| Age 18–24 | Age 25–34 | 0.6331 (0.110) | 1.1331 *** (0.000) | 0.5746 (0.149) | 1.1574 *** (0.000) | 0.6665 (0.092) | 1.1604 *** (0.000) |

| Age 35–44 | 0.5656 (0.170) | 1.1032 *** (0.001) | 0.6208 (0.132) | 1.1485 *** (0.000) | 0.6393 (0.121) | 1.1577 *** (0.000) | |

| Age 45–54 | 0.8921 * (0.035) | 0.8727 * (0.012) | 1.0338 * (0.015) | 0.8936 ** (0.010) | 0.9404 * (0.026) | 0.9099 ** (0.009) | |

| Age 55–64 | 1.0613 ** (0.010) | 0.3227 (0.392) | 1.2561 ** (0.002) | 0.3303 (0.382) | 1.0901 ** (0.008) | 0.3584 (0.341) | |

| Age > 64 | 0.2819 (0.572) | −0.0106 (0.982) | 0.5257 (0.293) | 0.0531 (0.907) | 0.3643 (0.464) | 0.0731 (0.872) | |

| Consumer loan experience | 1.5098 *** (0.000) | 1.0748 *** (0.000) | 1.4974 *** (0.000) | 1.0580 *** (0.000) | 1.4987 *** (0.000) | 1.0504 *** (0.000) | |

| Mortgage loan experience | −0.3127 (0.312) | 0.6839 *** (0.000) | −0.3797 (0.223) | 0.6449 *** (0.000) | −0.3435 (0.266) | 0.6275 *** (0.000) | |

| Living standards | −0.0002 * (0.011) | 0.0001 ** (0.004) | −0.0001 * (0.029) | 0.0001 ** (0.005) | −0.0002 * (0.011) | 0.0001 ** (0.005) | |

| Debt Literacy | −1.1772 ** (0.008) | −0.8196 * (0.014) | |||||

| Financial literacy | −1.0937 *** (0.000) | 0.0434 (0.859) | |||||

| Self-assessment | −0.0586 (0.412) | 0.0616 (0.285) | |||||

| constans | −1.3494 * (0.011) | −2.7423 *** (0.000) | −1.1491 * (0.033) | −2.8743 *** (0.000) | −1.3634 * (0.015) | −3.0644 *** (0.000) | |

| Observations | 1300 | 1300 | 1300 | 1300 | 1300 | 1300 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0996 | 0.1003 | 0.0949 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurowski, Ł. Household’s Overindebtedness during the COVID-19 Crisis: The Role of Debt and Financial Literacy. Risks 2021, 9, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9040062

Kurowski Ł. Household’s Overindebtedness during the COVID-19 Crisis: The Role of Debt and Financial Literacy. Risks. 2021; 9(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurowski, Łukasz. 2021. "Household’s Overindebtedness during the COVID-19 Crisis: The Role of Debt and Financial Literacy" Risks 9, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9040062

APA StyleKurowski, Ł. (2021). Household’s Overindebtedness during the COVID-19 Crisis: The Role of Debt and Financial Literacy. Risks, 9(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9040062