Abstract

Nepotism and cronyism are forms of favoritism towards certain people in the workplace. For this reason, they constitute a problem for organization managers, ethicists and psychologists. Identifying the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the increase of nepotism and cronyism may provide a basis for organizations to assess their extent and to take possible measures to prevent their negative effects. At the same time, the research presented in the article may provide a basis for further research work related to nepotism and cronyism at the times of other threats, different from the pandemic. The aim of the article is to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on growing acceptance for nepotism and cronyism in Polish enterprises. Qualitative and quantitative methods have been included in the conducted research. Qualitative study aimed at improving knowledge of nepotism and cronyism and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these phenomena, followed by a quantitative study conducted in order to verify the information obtained in the qualitative study. This research has demonstrated that Nepotism and cronyism in the workplace, are phenomenon that are basically evaluated negatively. They adversely influences social and economic development, but the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on nepotism and cronyism is not significant.

1. Introduction

Both concepts, nepotism and cronyism, have negative potential. It results from the fact that in the case of nepotism it is about favoring the closest family members during the employment process without paying attention to their competences, and in the case of cronyism about friends and acquaintances (Riggio and Saggi 2015). Although it was not until the 16th century that Roman popes were accused of assigning high positions to immediate family members, nepotism-like practices had been and are still encountered throughout human history. Nowadays, when special attention is paid to the competences of employees, the issue of accepting to favor certain people is considered from the perspective of history, religion, sociology, political science, economics and law. With a religious perspective in mind, the phenomenon of nepotism is being studied in the structures of some Christian churches (Austin 2019). A practice that uses biased tools based on family relationships and acquaintances rather than competences and professionalism in the recruitment process is studied by psychologists dealing with its impact on employees who have to follow strict employment rules. Nepotism and cronyism put incompetent people in important positions and are thus the antithesis to valuing more qualified and effective people who cannot occupy high positions at work. This way, these phenomena work against the introduction of professional management, limiting the possibilities of effective management. Consequently, they have a negative impact on human resources, improving qualifications, as well as on attachment and loyalty to one’s company (Sidani and Thornberry 2013). From an ethical perspective, attention is drawn to the very moral issue of favoring people who are disqualified in the workplace and to some forms of discrimination. Lawyers, economists and people responsible for hiring employees see the negative economic effects in organizations where nepotism and cronyism are practiced, and therefore seek to limit this. The phenomenon of nepotism is also considered from the perspective of family businesses (Jaskiewicz et al. 2013; Hiebl 2015; Efferin and Hartono 2015; Liu et al. 2015; Cherchem 2017). Research on family businesses emphasizes that it is better for the future of the company to hire a competent manager who can professionally manage the company rather than to entrust it to incompetent family members (Bozer et al. 2017). The phenomenon of nepotism is widely discussed and criticized in developing and highly industrialized countries (Joffe 2004; Aldraehim et al. 2012; Popczyk 2017).

The phenomenon of nepotism is also considered from the perspective of various countries and regions. Knowledge of the level of acceptance for nepotistic practices enables better management of foreign capital in organizing workplaces and understanding nepotistic practices (Keles et al. 2011; Demaj 2012; Aldraehim et al. 2012; Sidani and Thornberry 2013; Vveinhardt and Petrauskaite 2013; Gustafsson and Norgren 2014).

The phenomenon of nepotism and its importance for the functioning of the organization has also been studied in Poland. Most often, these were articles based on studies comparing nepotism in Poland and Ukraine or Lithuania (Sroka and Vveinhardt 2020). Comparison of nepotism depending on membership in the public and private sector, age and gender, as well as Poland and Lithuania (Sroka and Vveinhardt 2020; Vveinhardt and Sroka 2020). The understanding of nepotism from the perspective of family businesses was also undertaken (Ignatowski et al. 2019). Ignatowski et al. (2020) dealt with the issue of acceptance for organizational nepotism from the perspective of belonging to the Protestant and Catholic denominations.

This text raises the issue of acceptance of nepotism during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of the article is to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on growing acceptance for nepotism and cronyism in Polish enterprises. In order to achieve the above-mentioned goal, the researchers put forward the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Nepotism is assessed more gently during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Cronyism is assessed more severely during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The negative impact of nepotism on workers is lower during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The negative impact of cronyism on workers is greater during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

Qualitative and quantitative methods have been included in the conducted research to verify these hypotheses.

2. Literature Review

It should be noted that the phenomena of nepotism and cronyism are not understood unequivocally. Overall, we can say that nepotism and cronyism are about favoring people in the workplace. The term “nepotism” is derived from the Latin word “nepos” which we translate as grandson or nephew. Hence, nepotism means favoring close family members in a given organization. Cronyism, on the other hand, comes from the word “crony”, which refers to the colloquial language used by Cambridge University students in the 17th century. This word was used to describe a person as “friend of long-standing”. Today, the term stands for favoring friends and acquaintances in the workplace. When it comes to favoring family members and friends, we sometimes also use the term “patronage” (Çarikçi et al. 2009). However, according to Arasli and Turner (2008), cronyism is referred to as favoritism and means granting special privileges to friends, colleagues and acquaintances during employment, further careers and making personal decisions. Both phenomena, nepotism and cronyism, however, are not limited to the employment process itself. They also cover the period of support during career development and favoring the person on the occasion of remuneration (Abdalla et al. 1998; Pelletier and Bligh 2008; Keles et al. 2011; Jones and Stout 2015). Bearing in mind family businesses, where we can encounter the phenomenon of nepotism much more often, in the literature on the subject we encounter the notions of “entitlement nepotism” and “reciprocal nepotism” (Jaskiewicz et al. 2013). However, the phenomenon of nepotism is usually viewed negatively in any company. Therefore, where it is not possible to find a qualified manager coming from the circle of the closest family, it is proposed to employ a qualified manager in a family business.

We most often encounter the phenomenon of nepotism where there are intense and traditional family ties and relationships, and where marketing principles are not developed, as is the case in highly industrialized countries. The choice of relatives is a natural phenomenon in the human world. According to the biological and ecological approach, nepotistic practices are rational behavior. The second factor that determines support for nepotism is the structure of the family and society. Where individualism prevails, nepotism will have less appreciation. In societies where traditional family ties dominate and individuals feel dependent, nepotism is an obstacle to economic and economic development. Individuals who trust only the family or its further members do not allow the establishment of free and independent relationships. Nepotism dominates in those countries where traditional relationships are more important than ethical obligations (Çarikçi et al. 2009).

Traditional family ties, their preferred values, and thus economic effects and organizations, are also influenced by religions, which influence how individuals perceive family loyalty as opposed to other members of society (Arruñada 2004; Sułkowski 2017; Allchin 2015; Arruñada and Krapf 2019). This, of course, influences the perception of nepotism (Treisman 2000). Research shows that in countries that arose from Protestant traditions, where there is a greater emphasis on individualism, there is less support for organizational nepotism (Filipova 2012; Ignatowski et al. 2020).

In the mid-nineteenth century, the study of human ethical attitudes revealed the process of transferring ethical issues from the sphere of philosophy and theology to the field of natural sciences, and human morality is justified in biology (Goatly 2006; Šamánková et al. 2018). This process is reflected in the evolutionary theory of ethnic solidarity, which allows us to understand why people can also support their friends and acquaintances beyond the circle of their closest family members. According to this theory, we cannot talk about supporting the closest family members, but rather about a genetic tendency to support other people in general. The tendency to become members of a different social group is present in all populations, indicating its evolutionary approach. For evolutionary solidarity to develop, there has to exist a significant capacity to sacrifice individual fitness for groups or populations that had ethnic characteristics (Allchin 2015; Salter and Harpending 2013).

Although we are generally faced with a negative assessment of the impact of nepotism on the organization, some authors, however in the minority, see its positive impact under certain circumstances. They include the existence of natural kin-related ties in the transmission of knowledge and greater responsibility (Jaskiewicz et al. 2013). We see the claim that family members with a positive reputation can, under certain circumstances, transfer that reputation to the organization (Okyere-kwakye et al. 2010). In some publications, we encounter arguments that testify to the positive importance of nepotism, namely, that family members of a recognized leader can gain the trust of other members of the organization. Another argument is the belief that they gain greater trust and loyalty and commitment to the organization themselves (Dickson et al. 2012). The culture of enterprises in which families have a definite advantage is more conducive to actions than the culture of enterprises in which there is no family domination. Pfeffer (2005) defends nepotistic employment as a way to create a “communal organization” that seeks to build a sense of community at work and shows holistic concern for workers, in contrast to the more restricted and transactional approach that many organizations adopt in their relationships with employees (Pfeffer 2005; Padgett et al. 2015).

However, most researchers point to the negative importance of nepotism (Pearce 2015; Sroka and Vveinhardt 2018; Sroka and Vveinhardt 2020; Vveinhardt and Sroka 2020). Research shows the negative impact of nepotism either on the organization itself, or on the employees who face this phenomenon. The respondents show that nepotism negatively affects job satisfaction (Arasli et al. 2006; Arasli and Turner 2008; Padgett et al. 2015). This negative impact is also expressed in negative attachment to the organization (Padgett and Morris 2005; Padgett et al. 2015) and the motivation of employees (Padgett et al. 2015) who witness nepotism and have no benefits for it. Nepotism also reduces trust in the organization (Keles et al. 2011) and increases stress among employees (Basu 2009). With the increase of nepotism, the intention to leave the organization also increases (Keles et al. 2011). People who take a negative stance towards nepotism will be less favorable to people who have been employed according to nepotism practices and will be able to stigmatize them. People who have been employed under nepotistic practices will be considered less competent than those who have been employed under the applicable rules and therefore deserve lower wages and will generally be viewed less favorably by other workers (Padgett et al. 2015).

From the perspective of a professional ethicist, both cronyism and nepotism can be a problem. They negatively affect not only the satisfaction with the work and its performance, but also weaken morale and attachment to the organization. Despite all these negative effects, it should be remembered that nepotism is legally limited with a certain reserve (Fu 2015). The reason is not mainly indicated on the positive sides of the phenomenon, but rather ethical dilemmas. Introducing drastic restrictions on employing people in a nepotistic way can lead to some form of discrimination. Family members are denied employment just because they belong to decision-makers in a given organization (Fershtman et al. 2005). The introduction of strict nepotism rules can put an organization in a difficult position. It turns out that the introduction of rules aimed at preventing the employment of unqualified family members led to a ban on the employment of qualified individuals who were spouses of current employees. There are even worse situations when colleagues who meet at work fall in love with each other and want to get married. Most likely, they were both employed on the basis of their competences. An anti-nepotism policy can lead to a situation where one of the parties has to be transferred to another department or leave the organization completely (Fisher 2005). The strict rules in this respect introduced in the American public sector in the mid-nineties of the last century meant that women had to change jobs more often than men (Williams and Laker 2010).

The sources of organizational nepotism should be sought in strong family ties. It does not change the fact that it has been present in all civilizations in the world and we meet it in all sectors of public life. In this article, we ask whether the COVID-19 pandemic is having an impact on increased acceptance of nepotism. Such a statement is justified by the fact that with the spread of the pandemic, unemployment increases, and at the same time restrictions in the economic field help tighten family ties. The fact that we are dealing with the pandemic was confirmed on 11 March 2020 by the chairman of the World Health Organization, who said during a press conference that the coronavirus causing the COVID-19 disease can be considered a pandemic. He added that all countries must find the right balance between protecting health, minimizing economic and social disruptions and respecting human rights. WHO is working with many partners around the world to mitigate the social and economic impact of the pandemic. In the case of COVID-19, we cannot speak of a crisis that affects public health, but it will affect all people and everyone must get involved in fighting this crisis (WHO 2020).

During the pandemic, there were a number of radical economic and lifestyle changes. First of all, the world, including enterprises, was not prepared for the situation of a global pandemic (Belzunegui-Eraso and Erro-Garcés 2020). This resulted in a number of difficulties in running a business, in extreme cases resulting in the disruption of supply chains. Entire industries whose specificity of operation forced the necessity of interpersonal contacts (most services addressed to individual recipients, tourism, passenger transport) were “switched off” or their activity was severely limited.

At the same time, many employees had to switch to remote work via social messaging and teleworking. Its use on a mass scale was a complete novelty for many organizations (Toshihiro 2020; Sostero et al. 2020; Katsabian 2020; Fana et al. 2020). Teleworking, although generally assessed positively by many, met with a number of negative opinions, especially by men and the older generation. The most important disadvantages include the inability to demonstrate exceptional skills, difficulties with proper assessment by superiors of their results and competences or problems with asynchronous communication and work organization. At the same time, teleworking was rated worse by older workers. Lack of direct contact and feedback decreased motivation and trust (Raišienė et al. 2020; Baert et al. 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has also changed the approach to formulating an organization’s sustainable development strategy. Its effects and the lack of preparation of most organizations in the world clearly showed that such pandemics must be considered as one of the important elements of a sustainable development strategy (Ikram et al. 2020). At the same time, research on Spanish companies during the COVID-19 pandemic showed the importance of organizational ethics and corporate social responsibility, the improvement of which may lead to greater employee satisfaction (Castellanos-Redondo et al. 2020). A certain positive influence of the family on the functioning of enterprises was also noticed, characterized by greater solidarity and cohesion in family enterprises (Kraus et al. 2020).

A direct effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was also a slowdown in the development of most of the world’s economies (Derkacz 2020; Soava et al. 2020; Islam et al. 2020). The economic changes also resulted in increasing unemployment and lowered salaries, which influenced the course of professional careers (Al-Youbi et al. 2020; Every-Palmer et al. 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the lifestyle of Europeans, although the level of changes varies depending on the country, most often depending on the intensity of the epidemic in the countries studied (www.ircenter.com 2020). Among the changes, one of the most important is the increase in the importance of family and family ties, while at the same time the activity with friends has decreased (Vatavali et al. 2020; www.ircenter.com 2020). Human relationships will also be more respected (www.ircenter.com 2020). Remote work and the need to stay at home allowed to spend a lot of time with my family (Every-Palmer et al. 2020). At the same time, restrictions related to COVID-19 (quarantine for the sick, prohibition of movement, ban on assemblies, ban on contacts with hospitalized persons) significantly impeded the cultivation of family ties with members who were not in the same household during the pandemic (Annonymous 2020). Domestic violence increased in closed families as a result of restrictions (Usher et al. 2020; Campbell 2020; Humphreys et al. 2020; Prime et al. 2020; Lebow 2020; Xue et al. 2020; Pereda and Díaz-Faes 2020; Zhang 2020).

The pandemic also increased the level of depression and anxiety (Serafini et al. 2021, p. 8; Bourion-Bédès et al. 2020; Kar et al. 2021, pp. 3–4; Cénat et al. 2020; Vatavali et al. 2020; Mechili et al. 2020; Every-Palmer et al. 2020; Mazza et al. 2020; Ettman et al. 2020; Rehman et al. 2021; Nader et al. 2020; Ma et al. 2020; Bäuerle et al. 2020; Oducado et al. 2021, p. 76). Satisfaction with life decreased (Blasco-Belled et al. 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is also a series of pseudoscientific information about the epidemic, having a negative impact on the mental health of the society (Escolà-Gascón et al. 2021). The quality of social capital played a significant role in the impact of COVID-19 on this health. The higher it was (especially its elements such as: interpersonal trust, community membership and social participation), the lower the negative impact of the epidemic was (Li et al. 2020).

At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic took many governments by surprise. Most of them had underinvested health care, which did not have sufficient resources to fight the global mass epidemic (Stawicka and Stawicki 2020). This resulted in the need to quickly replenish them, which was possible very often only thanks to intervention purchases. As a result, there were corruption abuses related to the purchase of medical equipment resulting from the loosening of anti-corruption rules in the name of accelerating the purchase and the lack of procedures for dealing with the pandemic (Steingrüber et al. 2020).

Summing up, it seems that the pandemic increased the importance of loyalty, honesty and clarity of principles in running a business, which should translate into lower acceptance for both nepotism and cronyism. At the same time, the previously described positive nepotism, when the employed family member has appropriate qualifications, may contribute to strengthening solidarity and cohesion in a family business. The increase in unemployment and turmoil in the labor market should result in an increase in nepotistic situations due to the redundant looking for shortcuts when looking for a new job. Teleworking, and the related lack of direct physical contact between employees, should facilitate the employment of family members and friends, because interpersonal contacts in companies, especially informal ones, are very limited, so it is easier for a recruiting manager to hide favoritism when hiring, which should also translate into growth the prevalence of both nepotism and cronyism. A higher scale of anxiety, depression and dissatisfaction with life should result in a more rigorous assessment of nepotism and cronyism in the organization. The authors of the article will examine whether the above changes in the scale of occurrence and assessment of nepotism and cronyism actually take place.

3. Materials and Methods

The main aim of the study was to investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the phenomena of nepotism and cronyism. For the purposes of the study, the following specific objectives have been formulated:

- Assessment of the impact of nepotism and cronyism from both entrepreneurs and employees before the pandemic.

- Assessment of the impact of nepotism from both entrepreneurs and employees during the pandemic.

- Employees and owners’ assessment of the impact of the pandemic on nepotism and cronyism.

In order to achieve the above research goals, the following research questions were asked:

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence the phenomena of nepotism and cronyism?

- Will a greater respect for family relationships result in a softer assessment of nepotism?

- Will a greater respect for family relationships reduce the negative impact of nepotism?

- Are there differences in the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic between nepotism and cronyism?

Based on the above-mentioned research questions, research hypotheses have been formulated. The hypothesis H1 and hypothesis H2 relate to the assessment of the phenomenon of nepotism and cronyism by both employees and owners. Based on literature research, it can be stated that the former assess both nepotism and cronyism negatively, while business owners evaluate nepotism positively due to the specificity of family businesses, and cronyism—negatively (Sroka and Vveinhardt 2018; Onoshchenko and Williams 2014; Williams and Onoshchenko 2014; Padgett and Morris 2005; Padgett et al. 2015; Abdalla et al. 1998; Vveinhardt and Sroka 2020). At the same time, the competences and skills of the employed person have an impact on the assessment of nepotism. Due to the strengthening of family relationships, as a result of the pandemic (Vatavali et al. 2020; www.ircenter.com 2020) it is assumed that the impact of the pandemic will result in a milder assessment of nepotism. On the other hand, increasing the importance of corporate social responsibility and organizational ethics (Castellanos-Redondo et al. 2020) should lead to a more rigorous assessment of the above-mentioned phenomena. Therefore, it is assumed that the assessment of cronyism during the pandemic will be more severe. Based on the above knowledge, two further research hypotheses have been formulated.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Nepotism is assessed more gently during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Cronyism is assessed more severely during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

In the course of the conducted literature studies, the influence of nepotism and cronyism on a number of factors related to the functioning of the company have been identified. Generally, nepotism and cronyism negatively affect employee satisfaction, motivation to work, employee commitment, trust in the organization and willingness to work in the organization (Padgett and Morris 2005; Padgett et al. 2015; Abdalla et al. 1998; Arasli et al. 2006; Qaisar 2016; Keles et al. 2011; Vveinhardt and Petrauskaite 2013). However, in family businesses, due to their specificity, nepotism may have a positive impact on: o reducing the scale of conflicts at the owner-manager level, loyalty of managers, sharing knowledge between managers, involvement of managers in the company (Lin and Hu 2007; Popczyk 2017; Padgett et al. 2015). At the same time, if the employed family manager has the appropriate qualifications, they can have a positive impact on employee commitment in the company (Padgett et al. 2015). Due to the strengthening of family relations (Vatavali et al. 2020; www.ircenter.com 2020) the COVID-19 pandemic should result in a reduction of the negative impact of nepotism on employees. At the same time, increasing the importance of corporate social responsibility and organizational ethics (Castellanos-Redondo et al. 2020) should lead to an increase in the negative impact of the above-mentioned phenomena. Therefore, the following research hypotheses have been formulated:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The negative impact of nepotism on workers is lower during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The negative impact of cronyism on workers is greater during the COVID-19 pandemic than before it.

In order to verify the above research hypotheses, both qualitative and quantitative methods were included in this study. As part of the qualitative method, an individual in-depth interview was used. Its main goal was to test the acceptance of the phenomenon of organizational nepotism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to some discrepancies in the approach to the terminology of nepotism itself in the literature on the subject, it was first attempted to determine how it is understood by the owners of the surveyed companies. During the interviews, attempts were also made to check whether the entrepreneurs perceive the negative or positive effects of practicing nepotism.

The interviews were conducted between 3 December 2020 and 20 December 2020 with the owners of 11 companies operating during the COVID-19 pandemic. The choice of the dates of the interviews was not accidental. At that time, administrative constraints intensified compared to the previous ones, which prevented companies from operating more fully not only in Poland, but also around the world. The choice at this stage of the research made it possible to reach specific cases and gave the opportunity to understand the specificity of the phenomenon under study and the operating enterprises (Stake 2010; Sułkowski 2009; Fendt and Sachs 2008; Jackson et al. 2007). The individual in-depth interviews were based on a repeatable research scenario, which gave the respondents the opportunity to ask additional questions, which allowed for more detailed research issues. Before conducting the research, the scenario was consulted with external experts dealing with the functioning of enterprises in times of threats and crises. Two of the experts came from academia and the other two from organizations dealing with crisis strategies. The interviews were recorded and then transcribed and subjected to qualitative analysis. In cases where the analyzed issues required further explanations, communication with the surveyed entrepreneurs was carried out using reliable Internet platforms for online meetings, telephone calls, and also during face-to-face conversations.

The selection of respondents was deliberate. The survey was participated by owners and managers of companies who run their businesses during the pandemic and, despite difficulties, do not lay off but employ working staff. They were representatives of two companies providing accounting services operating in a city with over 750,000 inhabitants. Another respondent was a person operating in the press industry in a city with more than 750,000 inhabitants. Two more companies operate in the service and construction industry. However, the first one is located in a city with more than 750,000 inhabitants, and the other one, in a town with less than 5000 inhabitants. The study included one company operating in the tourism and one transport industry. The first one operates in the tourism industry and is located in a city with less than 100,000 inhabitants, the other in a city with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Two other companies conduct hairdressing and beauty activities and operate in cities of over 100,000 inhabitants and less than 43,000 inhabitants. The last two companies operate in the catering industry. The first operates in a town with more than 43,000 inhabitants, and the other one with less than 100,000. The selection of respondents in the qualitative research is presented in the Table 1:

Table 1.

Business taking part in the qualitative study.

In the second stage of the study, a quantitative study was conducted in the form of two surveys, the first of which took place in spring 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the other one in November 2020, during the fall peak of the pandemic. Due to the fact that two questionnaires with identical questions were carried out, it was possible to compare the respondents’ opinions on phenomena related to nepotism and cronyism before and during the pandemic.

The first survey was conducted on a group of 510 first and second cycle students of a large university in Poland in the form of an auditory survey. The vast majority of these students are already working, so they have the experience necessary to answer the survey questions. A similar sample was used by Padgett, Padgett and Morris in their research (Padgett et al. 2015; Padgett and Morris 2005). The study was conducted in centers located in both large cities as well as in smaller ones. A questionnaire with four extended principal questions was used for the study, two of which were used for the analysis and three questions for the statistical information. All questions were closed and complex measuring scales were used. The structure of the respondents is presented in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Structure of respondents in the first survey.

The second survey was conducted on a group of 601 first and second cycle students of the same university in the same fields of study to obtain a very similar research sample. The vast majority of students are already working, and therefore, have the experience necessary to answer the survey questions. For epidemiological reasons, the questionnaire was in the form of an online questionnaire, and the students were asked to complete it during remote classes, so that it would correspond to the first questionnaire as much as possible. A questionnaire with three extended principal questions and three statistical questions was used for the study. All questions were closed and complex measuring scales were used. The structure of the respondents is presented in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Structure of respondents in the second survey.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Research Results

Qualitative research showed that the owners of the surveyed companies understood the phenomenon of organizational nepotism in two ways. Nepotism was understood either as the employment of a close family member, or in general, as favoring not only family members but also friends and acquaintances. After explaining the differences, they showed understanding for both the concepts of “nepotism” and “cronyism”.

The research has shown that not all entrepreneurs were able to point out some of the potential positives and negatives of nepotism and cronyism without much difficulty. The potential benefits were easily listed for people employed in accounting, press and tourism services, which does not mean that they accepted them (F1, F2, F3, F6). Due to the pandemic situation, “competences are even more important” (F2). They pointed to the need to hire professionals, even in a pandemic situation. “I cannot imagine working with non-professionals, even in a pandemic,” said the first (F1). “At a time when confidence in the press and journalism is declining, the situation caused by the pandemic requires even greater professionalism and commitment” (F3). The tourist service representative emphasized that “it is not enough to seat a loved one behind a desk to sell tickets, especially in times of the coronavirus pandemic” (F6). On the other hand, the representative of the hair and beauty industry approached cronyism and nepotistic attitudes with some approval. As the owner of a family business, he indicated that thanks to employing friends, he “has great trust in his family” (F8). The second of them “trusts his brother very much and he cannot imagine the functioning of the company without him” (F9). Therefore, if he had to choose between two professional candidates, he would “choose a family member or a trusted friend” (F9). The trust issue was developed by the food service representative (F10 and F11). The second of them confessed that “when he employed only people from outside his family, money was missing in the cash register”. Now they are missing too, “but to a much lesser extent.” Professionalism “was not the most important” for the first of them (F10). Similarly, trust, as one of the positive factors in employing friends, was indicated by representatives of the transport and construction services company (F7, F4 and F5). The owner of the transport company noted that “he can call a friend and solve the current case at any time” (F7). During the epidemic, “trust is the basis of cooperation and mutual trust” (F5). Representatives of companies dealing with accounting services approached the issue in a similar way. Because they run a family business themselves, they cannot imagine that you cannot trust your spouses. However, they cannot imagine that they are “without competence” (F1 and F2). According to the representative of the press industry, “trust is not based on family ties, but on the experience gained” (F3). It is interesting that representatives of the catering industry indicated gratitude as a positive element in terms of nepotism and cronyism. This gratitude is “especially felt in a pandemic” (F11). According to him, when he employs family members, he can “count on greater gratitude”. The phenomenon of nepotism results “from gratitude to the family and willingness to help relatives, including friends,” declared another representative of the catering industry (F10). For representatives of the construction industry, there is no need to waste time searching for employees (F5), and home experience is “essential for survival during a pandemic” (F4).

The research showed that the respondents were aware of the many negatives of hiring according to nepotistic rules. At the same time, regardless of the state of the pandemic, there is a negative impact on the attitudes of employees and the condition of the company. The most common disadvantages were difficulties in distinguishing between work and family relations. The representative of the catering industry indicated the blurring of the boundaries “between family relations and employees” (F11). He pointed out that “an example may be a married couple who run a business together”, “financial problems are transferred home, and family problems—to work”. These problems may worsen in a situation of “reduced mobility and service provision” (F11). In a married couple, “spending all the time together negatively affects the relationship, as it may turn out that a man cannot share anything else with a loved one”, which is the case “especially during a lockdown” (F10). Above all, difficulties arise when disciplinary action should be taken. Such difficulties are indicated by the representative of the construction industry (F4 and F5) and hairdressing and beauty services (F6). For the first of them, “it would be difficult to reprimand your loved ones” (F4). How could I, as the representative of the construction industry said directly, “let my brother-in-law, with whom we spend all the holidays together, be fired” (F5). “It is always difficult, and even more difficult in the present situation” (F5). The representative of the hair and beauty industry does not have such experiences directly. He adds, however, that “he cannot imagine a situation when he would have to call his closest relatives to his office.” A difficult conversation would also be “in a situation of disciplining colleagues” (F8). The representatives of the press and construction and renovation industries indicated the employment of people without qualifications (F6). Some people think that everyone knows politics and therefore “could easily comment and write columns relating to current political affairs” (F3). The representative of the catering industry explained that he did not want to hire his loved one, and in such a situation he indicated a lack of qualifications. In response, he heard that “everyone can cook” (F10). Which is due to the fact that close relationships obscure objectivity.” (F11). The need to require qualifications means that representatives of accounting services do not hire their friends. On the contrary, “I cannot imagine that someone without qualifications, and at the same time a family member, could work in my company” (F1). The other representative of the accounting services stressed that “I am personally against hiring relatives because I believe that the family should not be worked with” (F2). Their position does not change “also during a pandemic” (F1 and F2). The representative of the press industry pointed out the unfair treatment of employees. He noted that in the end “an entrepreneur may sooner or later feel the negative effects of nepotism”. He may be “harmed by family members” (F3). He will not be able to refuse help, and the lack of decision-making may lead to the collapse of the company (F5). It will be difficult for him to “exercise the appropriate competences or ask for their supplementation, if they are needed” (F9). Research on nepotism shows that by employing loved ones in some inexplicable way, we are convinced that “they have the required competences, even though we know that they do not have such” (F1 and F3). It does not change the fact that we may face completely different situations. Namely, relatives “will want to fulfill the hopes placed in them and the obligations imposed on them” (F6). The situation does not change during a pandemic, “particularly in the event of job loss” (F6). From a theoretical point of view, knowing that you are a family member, hired for a relationship, “can put so much pressure on those in employment that they will try to demonstrate greater competences” (F4). The same, and “maybe and even more we can encounter such attitudes during a pandemic” (F1).

The research has shown that representatives of the surveyed companies confirmed that there is a certain risk of increased acceptance for organizational nepotism during the Covid-19 pandemic. They resulted primarily from the drastic effects of lockdown restrictions. The representative of the catering industry claimed that “many companies and services are forced to close their businesses or lay off workers due to the epidemic.” It is different in a company based on family structures, where “you can leave your employee” (F10). The decisive factor in this is the ability to resolve financial issues “and this is easier with close family ties.” Disclosure of income and losses incurred (F9) is helpful in this regard. As he emphasized, “the same principle does not apply to close friends”. The epidemic is not limited to the suffered economic losses. Losses are also suffered by “employees, and the possibility of helping the loved ones makes it easier to solve ethical dilemmas, which makes it difficult to deny in these circumstances favoring the loved ones during the epidemic” (F11). The representative of transport services pointed to the lack of economic stability during the pandemic. Which, in his opinion, could “translate into an increase in acceptance for nepotism.” According to him, “every day he does not know whether an employee will come to work or not be quarantined” (F7). The fact that “I know the labor market and I can quickly find a person ready to work among family members allows the company to function” (F7). Nepotistic attitudes are also more accepted because of emotional family ties. As the representative of construction and renovation services says, “supporting the family in these moments is much more important than looking for a qualified employee in a foreign environment” (F4). The representative of hairdressing and beauty services admitted during the interview that the time of the pandemic favors both the phenomenon of organizational nepotism and even cronyism. He knows, but has not experienced it himself, that “many people have lost their jobs. They were replaced by relatives to help the company with financial difficulties survive the difficult times” (F9). Which does not mean that he accepts such solutions himself. Such a situation is harmful to the dismissed people, but it is at the same understandable time. With the help of the family, “it is easier to avoid business closure and fight for its survival” (F9). It should be noted, however, that different approaches to the pandemic and the resulting practices were obvious to the representative of the press industry. He stated that “we encounter the phenomenon of nepotism more than once. Nowadays much more often” (F3). The pandemic did not essentially justify the use of nepotism by employers who have the opportunity to work remotely. The research has shown that acceptance of nepotism can also be justified beyond material considerations and family and friendship ties. The representative of the press industry admitted that the pandemic makes people feel unsafe. “It is therefore possible to depart from certain obligations for the benefit of the family and loved ones” (F3).

Summing up, it should be stated that the qualitative research has shown that the phenomenon of nepotism is accepted to some extent in some of the surveyed companies. It is less so in the case of cronyism. There was a different approach to nepotism, and it results from the specificity of the business. Where finances are concerned, there is basically no nepotism or cronyism. Where activity is online, there is less acceptance, and we see greater acceptance in the case of complete limitation of the activity. Let us note that the respondents showed, after some explanations, knowledge of the discussed issues and were able to indicate what nepotism and cronyism are. If they were unfamiliar with this distinction, they understood that it was about employment and its consequences. However, after explanations, they agreed that such a distinction is necessary and sheds light on the issue of favoring people in the workplace. It is worth noting that some interviewed people noticed some benefits of nepotism in dealing with pandemic problems. In difficult times, the trust and devotion of a family member turned out to be more important and useful for the family business than the qualifications of outsiders. This result is consistent with the research on companies in New Zealand, where also trust and devotion resulting from belonging to a family facilitated the survival of companies in situations of high uncertainty (Wu 2020). The trust in the closest family members underlined in the research results not only from experience, but also finds its deep confirmation in sociological research. According to them, Poles place the greatest trust in their closest family members. This is significant because Poles also belong to communities that have a low level of trust in others compared to other European nations. Acceptance for the activities of nepotism also results from the limitations resulting from the need to respect procedures, as “searching for employees in times of a pandemic turns out to be difficult” (F7).

4.2. Qualitative Study Results

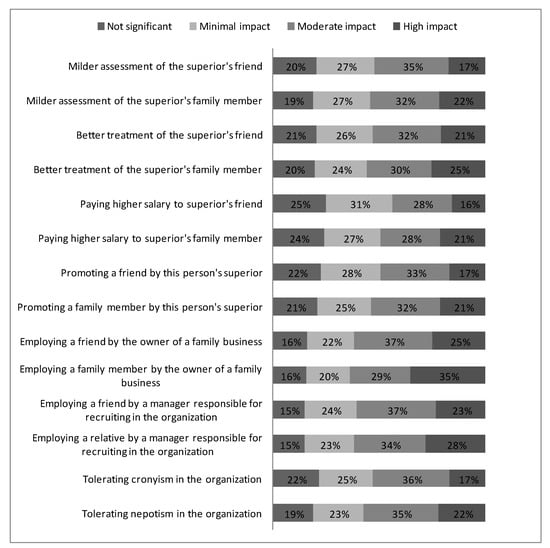

In the first question, the authors examined the respondents’ opinions on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the phenomenon of nepotism. The assessment of the opinions on this impact was based on the fact that the respondents determined the impact of the pandemic on nepotism and cronyism and then, using the same scale, the impact on selected specific phenomena related to nepotism and cronyism. A scale with four possible answers was used for the answers: no significance, minimal impact, moderate impact, and high impact.

In the opinion of most respondents, the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the tolerance of nepotism in the organization (Figure 1). According to the respondents, it will mainly be manifested in the employment of people related to the owners of the company in the family business (64.06% of respondents indicated that the pandemic will have a moderate and high impact in such situations). The risk of employing people related to managers responsible for recruitment in non-family companies was mentioned less often (61.90%). The impact of the pandemic on other nepotistic situations (e.g., in promotions, paying higher wages, better treatment, or less favorable assessment of relatives) was believed to have little or no impact by approximately half of the respondents, while the other half thought it would be moderate and high. Thus, the opinions here are divided. The percentage of respondents who say the pandemic will affect the tolerance of cronyism is noticeably lower. It was pointed out slightly less frequently that the pandemic would have an impact on hiring friends and other forms of favoring friends (compared to favoring relatives).

Figure 1.

Impact of the Covid pandemic on phenomena related to nepotism and cronyism—opinions of the respondents. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

In the next step, the authors decided to examine whether the workplace influences the respondents’ opinions. They were divided into five groups: working in family businesses, working in non-family businesses, working in the public sector, running their own business and not working.

The analysis of the data in Table 4 shows that the respondents most often assessed the impact of the Covid pandemic on the tolerance of nepotism in the organization, as moderate 35.4% (213 people) and only 19% (114 people) described the impact of the Covid pandemic as non-significant. A high or moderate influence on tolerating nepotism in the organization, depending on the workplace, was most often indicated by business owners 61.1% (18 people), and the least by the respondents working in family businesses 44.2% (23 people). Almost two-thirds of the owner indicating the impact of the pandemic on the employment of relatives confirms the information obtained in qualitative research that some owners prefer to support their relatives in difficult times. On the other hand, the responses of people working in family businesses, i.e., those in which the owners’ relatives may actually be employed, suggest that this phenomenon has not escalated in family businesses as expected, since this impact is clearly less often indicated by these employees than in other groups.

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the Covid pandemic on the tolerance of nepotism depending on the workplace.

Statistical analysis showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of tolerating nepotism in the organization depending on the workplace. Detailed data is presented in Table 1.

In the next step, opinions on tolerating cronyism were compared. The analysis of the data in Table 5 shows that the respondents most often assessed the impact of the Covid pandemic on the tolerance of nepotism in the organization as moderate 35.8% (215 people) and only 17.1% (103 people) described the impact of the Covid pandemic as having no significance. A high or moderate influence on tolerating nepotism in an organization, depending on the workplace, was most often indicated by company owners (58.6%) (17 people), but a similar percentage of people working in the public sector also indicated a high or moderate influence (58.1%). High and moderate influence was the least frequently indicated by the respondents working in non-family businesses 50% (119 people). Therefore, here too, it seems that business owners who feel the effects of the pandemic the most, are often the ones to see the pandemic as conducive to favoritism.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the Covid pandemic on the tolerance of cronyism depending on the workplace.

The statistical analysis showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of tolerance of cronyism in the organization depending on the workplace. Detailed data is presented in Table 5.

Following this, the analysis of selected situations of favoring selected people in organizations was undertaken. First, it was checked: what are the opinions on the impact of the pandemic on employing family members by managers (not owners) depending on the place of work. The number of people related in this organization was moderate—33.6% (202 people) and only 14.8% (89 people) described the impact of the Covid pandemic on this situation as non-significant. High or moderate impact on employing family members by managers (not owners), depending on the place of work, was most often indicated by 67.8% (99 people) the respondents who were not working, and the least by 55.2% (16 people) by the respondents running their own business. Similar indications were also obtained among employees of family businesses 55.8% (29 people).

Statistical analysis showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the employment structure of the manager responsible for the recruitment of a related person in this organization depending on the workplace. Detailed data is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the Covid pandemic on employing a family member by the manager responsible for recruitment in the organization depending on the workplace.

In the next step, opinions on the employment of a related person in the company by the owner of the family business were analyzed. The analysis of the data in Table 7 shows that the respondents most often assessed the impact of the Covid pandemic on the employment of a related person by the owner of a family business as high—35.4% (213 people) and only 15.6% (94 people) assessed the impact of the Covid pandemic on this situation is irrelevant. A high or moderate impact on the employment by the owner of a family business of a related person in this company depending on the place of work was most often indicated by those working in the public sector 66.2% (90 people) and the least by the respondents working in a family business 59.6% (31 people). The differences between the groups in this case were not large. It should be added that although business owners indicated a moderate and high impact less frequently than those not working or working in the public sector and in non-family enterprises, they most often indicated this impact as very high. This suggests that almost half of them may be considering hiring a family member in their business.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the Covid pandemic on employing a family member by the owner of the family business depending on the place of work.

The statistical analysis did not show any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of employing a person related to him by the owner of the family business in this company depending on the workplace. Detailed data is presented in Table 7.

The next analyzed cases concern cronyism. The first is when the recruiting manager hires a friend in this organization. The analysis of the data contained in Table 8 shows that the respondents most often assessed the impact of the Covid pandemic on hiring a manager responsible for recruiting a friend as moderate 37.4% (225 people) and only 14.8% (89 people) said that the impact of the Covid pandemic on this situation does not exist. A high or moderate impact on the employment of a manager responsible for recruiting a friend, depending on the place of work, was most often indicated by those not working 65.1% (95 people) and the least by the respondents running a business 51.7% (15 people).

Table 8.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the Covid pandemic on employing a friend by the manager responsible for recruitment in the organization depending on the workplace.

The statistical analysis showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of employment by the manager responsible for recruiting a friend depending on the workplace. Detailed data is presented in Table 8.

The second situation concerns cronyism in a family business. The analysis of the data contained in Table 9 shows that the respondents most often assessed the impact of the Covid pandemic on employment by the owner of a friend’s family business in that company as moderate 36.8% (221 people) and only 16.3% (98 people) described the impact of the pandemic Covid as non-significant. High or moderate impact on employment by the owner of the family business of a friend in this company, depending on the place of work, was most often indicated by those working in the family business 67.3% (35 people) and less by business owners 61.06% (18 people) and the least working in the sector public 51.7% (15 people).

Table 9.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the Covid pandemic on employing a friend by the owner of the family business depending on the workplace.

Statistical analysis showed a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in the structure of employment by the owner of a friend’s family business in this company depending on the place of work, i.e., employees employed in the family business statistically significantly indicated a greater impact of the Covid pandemic on employment by the business owner family friend in this company than other people. Detailed data is presented in Table 9.

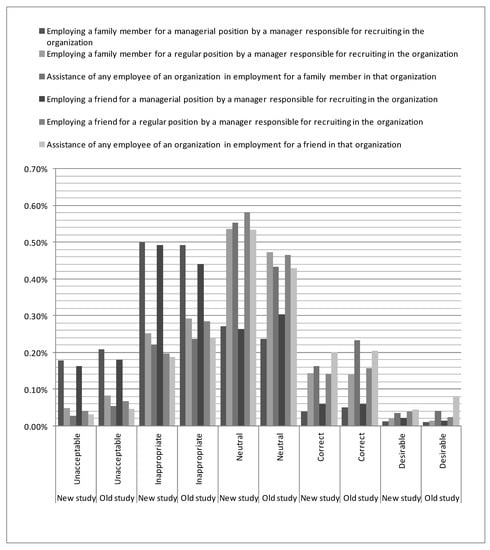

In the second block of questions, the authors decided to examine how the assessment of situations related to favoring others has changed during the Covid 19 pandemic. To assess situations related to favoritism, a five-point scale was used with the following possible answers: unacceptable, inappropriate, neutral, correct, or desirable. By comparing the answers of the respondents from before the pandemic with those during the pandemic, it is possible to determine how the attitude of the respondents to these situations changes. First, the change in the assessment of employment situations with the use of nepotism and cronyism in a non-family enterprise was examined.

Most of the respondents assessed the situations in which there was help in employing non-family enterprises as negative. The situations in which the employee held a managerial position were treated the most severely, and there is no significant difference in this situation between nepotism and cronyism. The help of ordinary workers in recruiting their family members and friends to regular positions was rated the least favorably. Therefore, along with the decline in the rank of the position, the percentage of respondents assessing it negatively decreased.

There were no significant differences in the assessment of these situations by respondents in the pre-pandemic period and during the pandemic. Although the number of respondents negatively evaluating employment for managerial positions was slightly lower during the pandemic, the help of ordinary workers in hiring was more often indicated as desirable, before the pandemic, fewer people indicated all the above situations as unacceptable, the differences are small and fall within statistical error limits. Detailed information is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Assessment of employment situations with the use of nepotism and cronyism in a non-family business. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

The analysis of the data in Table 10 shows that the respondents most often assessed the employment by a manager responsible for recruiting a related person for a managerial position as inappropriate 49.5% (550 people) and only 1.1% (12 people) as desirable. Inappropriate and unacceptable assessment of employing a manager responsible for recruiting a related person for a managerial position depending on the date of the study was indicated more often in the study conducted before the Covid 19 pandemic, 70.1% (357 people). The correct and desirable assessment of employing a related person for a managerial position by a manager responsible for recruiting a related person also appeared more often in the study before the pandemic 6.1% (31 people). However, in both cases the difference between the old and new studies was small.

Table 10.

Statistical analysis of assessment of employing a relative for a managerial position by a manager responsible for recruiting depending on the date of the survey.

Statistical analysis did not show any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the employment structure by the manager responsible for recruiting a related person for a managerial position depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 10.

The analysis of the data in Table 11 shows that the respondents most often assessed the employment by a manager responsible for recruiting a friend for a managerial position as inappropriate 46.9% (521 people) and only 1.8% (20 people) as desirable. The inappropriate and unacceptable assessment of employing a manager responsible for recruiting a related person for a managerial position depending on the date of the study was indicated more often in the study conducted during the Covid 19 pandemic, 65.6% (394 people). Correct and desirable assessment of employing a manager responsible for recruiting a friend for a managerial position also appeared more often in the study during the pandemic 8.2% (49 people). However, in both cases the difference between the old and the new study was small.

Table 11.

Statistical analysis of the evaluation of employing a friend for a managerial position by the manager responsible for recruiting depending on the date of the survey.

The statistical analysis did not show any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the employment structure by the manager responsible for recruiting a friend for a managerial position depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 11.

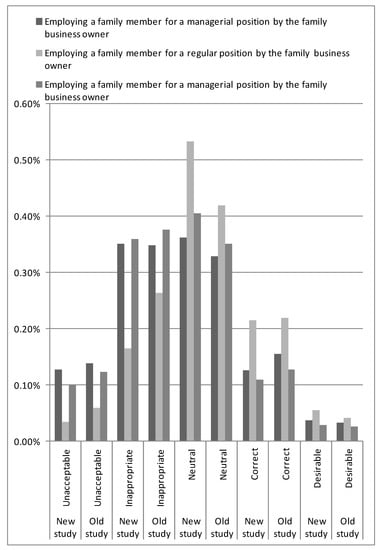

In the next questions, the authors examined the assessment of phenomena related to nepotism and cronyism in family businesses. Here, too, such situations were assessed negatively, and the percentage of respondents assessing them negatively also decreased with the decline in the rank of the position. There is a noticeable increase in the percentage of people assessing neutrally the employment of a family member for an ordinary position in a family business, with a clear decline in negative assessments of this phenomenon. Employing family members and friends for managerial positions is assessed similarly in both surveys (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Assessment of the employment situation by means of nepotism and cronyism in a family business. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

The analysis of the data in Table 12 shows that the respondents most often assessed the employment by the owner of a family business of a related person for a managerial position as inappropriate 35% (387 people), but the number of people assessing the above situation neutrally was similar to 34.6% (383 persons). In the study during the Covid 19 pandemic, the percentage of people assessing the above situation as neutral was higher than those assessing it incorrectly. Only 3.4% (38 people) of the respondents assessed this situation as desirable. Improper and unacceptable assessment of employing a related person by the owner of a family business for a managerial position depending on the workplace was indicated more often in the study conducted before the Covid 19 pandemic, 48.6% (246 people). The correct and desirable assessment of employing a related person for a managerial position by the family business owner was also more frequent in the pre-pandemic survey 18.6% (94 people). However, in both cases the difference between the old and new research was small.

Table 12.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of employment of a relative for a managerial position by the family business owner depending on the date of the study.

The statistical analysis did not show any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of employment by the owner of the family business of a related person for a managerial position depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 12.

The analysis of the data in Table 13 shows that the respondents most often assessed the employment of a friend for a managerial position by the owner of a family business as neutral 38% (421 people) and only 2.7% (30 people) as desirable. The inappropriate and unacceptable assessment of employing a friend for a managerial position by a family business owner depending on the workplace was indicated more often in the study conducted before the Covid 19 pandemic 49.7% (252 people). The correct and desirable assessment of employing a related person for a managerial position by the owner of a family business was also more frequent in the pre-pandemic survey 15.2% (77 people). However, in both cases the difference between the old and the new survey was small, although also in this case an increase in people assessing the above situation as neutral.

Table 13.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of employment of a friend for a managerial position by the family business owner depending on the date of the study.

The statistical analysis showed no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in the structure of employment by the owner of a family business, a friend for a managerial position, depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 13.

The last area studied was the evaluation of phenomena related to nepotism and cronyism, but not related to employment. Here, too, these phenomena were negatively assessed by the vast majority of respondents. There are also no major differences between pre- and pandemic testing. The exception is the evaluation of the promotion of relatives and friends. In the study, during the pandemic, the phenomenon of favoring people in promotion was assessed more mildly, though still negative by the vast majority. Detailed data is presented in Table 14.

Table 14.

Assessment of other situations related to nepotism and cronyism depending on the date of the study.

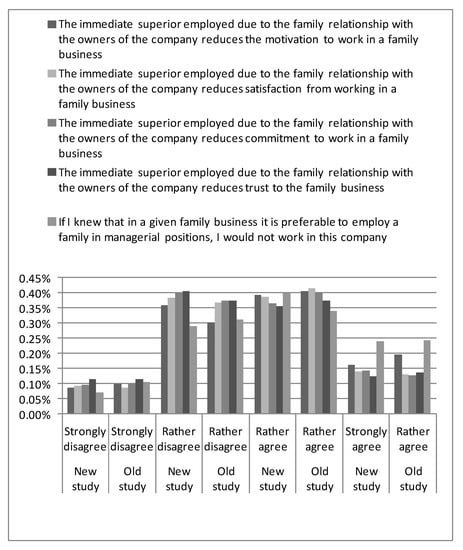

The last, third block of questions was to examine whether the pandemic had an impact on the functioning of employees in an organization with nepotism or cronyism. Previous studies indicate that both nepotism and cronyism negatively affect: employee satisfaction, motivation to work, employee commitment, trust in the organization and willingness to work in the organization (Padgett and Morris 2005; Padgett et al. 2015; Abdalla et al. 1998; Arasli et al. 2006; Qaisar 2016; Keles et al. 2011; Vveinhardt and Petrauskaite 2013). A four-point scale was used to assess the impact of favoritism in the workplace with the following possible answers: strongly disagree, rather disagree, rather agree, or strongly agree. By comparing the responses of the respondents before the pandemic with those during the pandemic, it is possible to determine how the impact of these situations on the respondents changes.

According to the respondents, nepotism in a family business has a negative impact on job satisfaction in a given organization (enterprise, institution, etc.), motivation to work, commitment, and trust in the organization or even the willingness to work in an organization where there is a phenomenon of nepotism consisting in employment due to kinship. Such an opinion was expressed by the vast majority of respondents. There are no significant differences in assessing the impact of nepotism before and during the pandemic (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The impact of nepotism on employees in a family business. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

The analysis of the data contained in Table 15 shows that the respondents most often agreed that the direct superior employed, due to the relationship with the owners of the company, reduces the motivation to work in a family business 39.9% (443 people) and only 9.1% (101 people) definitely did not match. In total, 60% (306 people) of the respondents in the pre-Covid 19 pandemic study strongly agreed and rather agreed. However, 44.4% (267 people) of the respondents to the study during the pandemic strongly disagreed and rather disagreed. The difference between the old and the new study was small, in the new study the percentage of people who did not agree with the above statement increased by less than 5% and the percentage of people who strongly agreed decreased by about 3%.

Table 15.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the employee’s immediate superior due to the relationship with the owners of the company on the motivation to work in a family business depending on the date of the study.

Statistical analysis did not show any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of the assessment of the impact of a related person’s employment by the owner of a family business on a managerial position on employee motivation to work depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 15.

The analysis of the data contained in Table 16 shows that the respondents most often disagreed that the direct superior employed, due to his relationship with the owners of the company, reduces the trust in the family business—39.1% (434 people) and only 11.35% (126 people) that it definitely did not, respectively. In total, 51.27% (261 people) of the respondents in the pre-Covid 19 pandemic study strongly agreed and rather agreed. However, 51.91% (312 people) of the respondents to the study during the pandemic strongly disagreed and rather disagreed. The difference between the old and the new study was small, within the limits of the statistical error. Thus, the impact of the pandemic has not been identified.

Table 16.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the employee’s immediate superior due to the relationship with the owners of the company on trust in the family business depending on the date of the study.

The statistical analysis did not show any statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in the structure of the assessment of the impact of employing a family business owner of a related person for a managerial position for trust in the family business depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 16.

In the next block of questions, the respondents assessed the nepotistic situations related to their functioning in non-family businesses. The negative impact of nepotistic situations on the functioning of employees in the organization is greater because the employees more often agreed with the statements contained in the questions. Almost two-thirds of the respondents agreed that a supervisor hired on the basis of kinship with the manager deciding on recruitment reduces motivation, about 60% of respondents also agreed that this situation reduces satisfaction, trust and commitment to work in the organization. The number of people who negatively assessed the above situations in the study during the pandemic was usually about 3–4% lower than before. Only in the case of motivation, there are no differences between the old and the new research. Detailed data is presented in Table 17.

Table 17.

Impact of nepotism on employees in a non-family business.

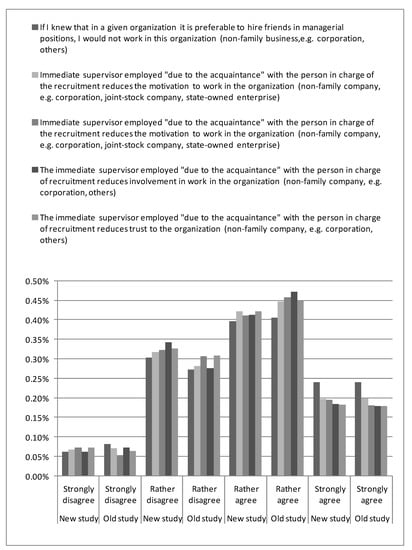

In the last set of questions of the third block, the respondents assessed the influence of cronyism on their functioning in the organization. As in the case of the impact of nepotism, the respondents rated the situations related to cronyism in the same way as before the pandemic. There was a slight decrease (1.2–5.6%) in the percentage of respondents agreeing with the statements about the negative impact of cronyism on satisfaction, motivation to work, commitment, and trust in the organization. Still, about 60% of the respondents agreed with the above statements, so cronyism for most of them had a negative effect on their functioning in the organization. Due to the slight differences between the research conducted before the pandemic and during the pandemic, we can say that this pandemic did not have a significant impact on the assessment of the phenomena related to the cronyism in the organization. Details are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Influence of cronyism on employees in a non-family business. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

The analysis of the data in Table 18 shows that the respondents most often agreed that the direct supervisor employed “due to their acquaintance” with the person deciding on recruitment reduces the motivation to work in the organization 43.3% (480 people) and only 6.9% (76 people) strongly disagreed. A total 66.7% (328 people) of the respondents in the pre-Covid 19 pandemic study strongly agreed and rather agreed. In contrast, 38.3% (230 people) of the respondents to the study during the pandemic strongly disagreed and rather disagreed. The difference between the old and the new study was small, in the new study the percentage of people who did not agree with the above statement increased by less than 3% and the percentage of people who strongly agreed decreased by about 3%. Thus, the impact of the pandemic on this assessment was negligible.

Table 18.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the immediate superior of the employed person “due to the acquaintance” with the person in charge of the recruitment on the motivation to work in the company depending on the date of the study.

The statistical analysis did not show a statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in the structure of the assessment of the impact of employment “due to their acquaintance” on a managerial position on employee motivation to work depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 18.

The analysis of the data contained in Table 19 shows that the respondents most often agreed that the direct supervisor employed “due to their acquaintance” with the person deciding about recruitment reduces the trust in the organization 43.4% (481 people) and only 6.8% (75 people) that it definitely did not. A total 62.9% (319 people) of the respondents in the pre-Covid 19 pandemic study strongly agreed and rather agreed. However, 39.8% (239 people) of the respondents to the study during the pandemic strongly disagreed and rather disagreed. The difference between the old and the new study was small, in the new study the percentage of people who did not agree with the above statement increased by less than 3% and the percentage of people who strongly agreed decreased by less than 3%. Thus, the impact of the pandemic on this assessment was negligible.

Table 19.

Statistical analysis of the assessment of the impact of the immediate superior of the employed person “due to the acquaintance” with the person in charge of the recruitment on trust in the company depending on the date of the study.

The statistical analysis did not show a statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in the structure of the assessment of the impact of employment “due to their acquaintance” on a managerial position on trust in the organization depending on the date of the study. Detailed data is presented in Table 19.

5. Discussion

The phenomenon of favoritism towards employees in the workplace, which includes nepotism and cronyism, has always been negatively evaluated and has had a negative impact on the functioning of a given organization. In general, all kinds of pandemics have negatively affected organizations and have contributed to the development of such phenomena as corruption, as well as nepotism (Teremetskyi et al. 2021). This text focuses on the question of the impact of the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus on the increased acceptance of nepotism and cronyism. To this end, four research hypotheses were posed.

Based on the research, the first research hypothesis “During the Covid-19 pandemic, nepotism is assessed more mildly than before it” has been verified negatively.

Although interviews with business owners suggested that hiring relatives may help to survive a difficult situation, they can, for example, help relatives and friends in the event of sickness-related absenteeism. Family employees can be trusted more and it is understandable that having a choice of the dismissal of an ordinary employee and an employee who is a family member the former will be dismissed, however, quantitative studies have shown only a slight increase in the acceptance of nepotism, usually within the limits of statistical error. At most, the respondents confirmed in the study that they expected an increase in the frequency of nepotistic phenomena, but this did not change their assessment. Therefore, it cannot be said that during a pandemic, nepotism is assessed more mildly.

To take the argument even further, in the literature it has been pointed out that the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus could eventually have a positive impact on reducing the acceptance of favoritism in the workplace. Nepotism, at least in countries like Romania, could then give way to meritocracy, in such sectors of public life as medicine, law and administration (Moasa 2020).

In addition, the second hypothesis “during the Covid-19 pandemic, cronyism is assessed more severely than before it” has not been positively verified.

Cronyism was assessed negatively, more severely than nepotism, which is consistent with previous studies of this phenomenon (Sroka and Vveinhardt 2018; Onoshchenko and Williams 2014; Williams and Onoshchenko 2014; Padgett and Morris 2005; Padgett et al. 2015; Abdalla et al. 1998; Ignatowski et al. 2019), however, the change in the respondents’ opinions on the assessment of cronyism, as in the case of nepotism, was insignificant. In addition, in the interviews with business owners, no arguments were made about a stricter assessment of cronyism during the pandemic. This situation may be due to the fact that cronyism is sometimes confused with nepotism and includes all forms of favoritism towards people in an organization (Mohdani et al. 2020).

Both qualitative and quantitative studies have confirmed that nepotism negatively affects the functioning of employees in the organization, reducing their satisfaction, motivation to work, employee involvement and trust in the organization. This is consistent with similar research by other researchers (Padgett and Morris 2005; Padgett et al. 2015; Abdalla et al. 1998; Arasli et al. 2006; Qaisar 2016; Keles et al. 2011; Vveinhardt and Petrauskaite 2013). Thus, the research results confirm the thesis that nepotism is a negative phenomenon contrary to those researchers who point out its positive sides or its tolerance (Jones and Stout 2015; Wated and Sanchez 2015). However, there was no change in respondents’ perceptions as a result of the pandemic. They were almost identical to those before the pandemic. Therefore, the third hypothesis “during the Covid-19 pandemic, the negative impact of nepotism on employees is lower than before it” has not been confirmed.

A similar situation was observed in the results on cronyism. Here, too, the respondents indicated the negative impact of cronyism on their satisfaction, motivation to work, employee involvement and trust in the organization, but again there were no significant differences between their opinions before the pandemic and during the pandemic. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis “during the Covid-19 pandemic, the negative impact of cronyism on employees is greater than it was before it” has also been verified negatively.

Both nepotism, understood as favoring the closest family members, and cronyism, as supporting friends and acquaintances in the workplace, are unfair forms of favoring people in the work environment. Since cronyism is more difficult to verify, it is not always strongly condemned. The conducted research shows that both phenomena occur during the pandemic. However, the state of the pandemic does not make them more accepted. Despite the fact that the state of the pandemic may foster closer family ties and lead to an increase in unemployment, which are considered to be an important element creating nepotism (Biroli et al. 2020). The long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic are not known yet, and therefore it is difficult to generalize whether in the long term there will be a change in the trend towards supporting nepotism (e.g., when negative health effects will lead to negative economic effects).