Value-Based Financial Risk Prediction Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

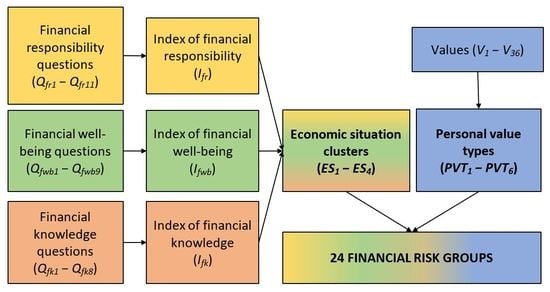

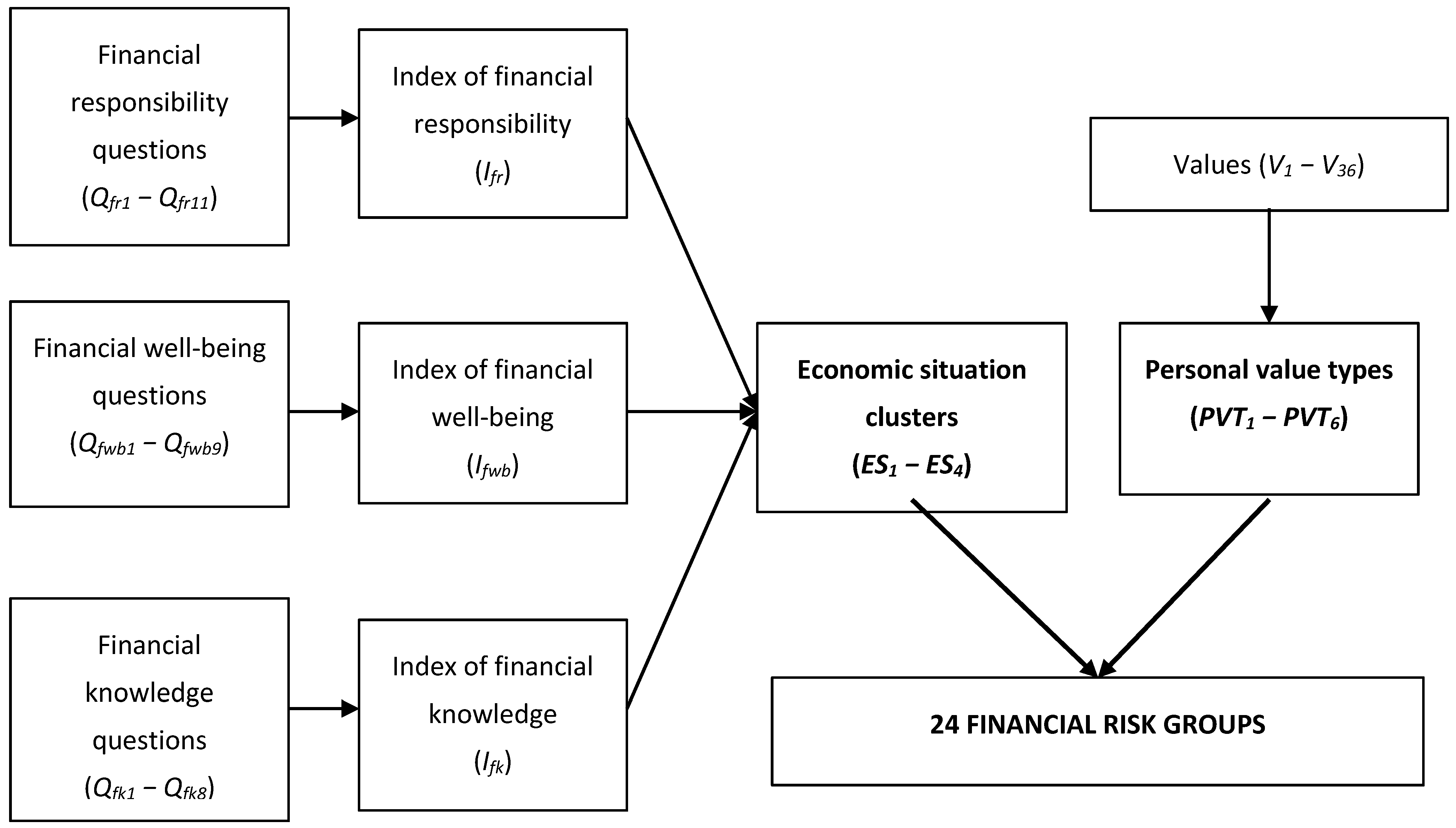

The Idea of a Financial Risk Prediction Model

- distinguish an individual’s economic situation and value type and predict his/her financial risk,

- to follow with either preventive measures or appropriate intervention.

2. Literature Review

- the most basic understanding of “a person’s competency for managing money”, “financial knowledge, perceived knowledge, financial behaviour and financial skills” and “understanding market principles, instruments, organizations and regulations”;

- through “familiarity with basic economic principles, knowledge of national economy and understanding of key economic terms”;

- to “familiarity with the most basic economic concepts needed to make sensible saving and investment decisions” (Hung et al. 2009; Remund 2010).

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data Measurements and Collection

3.2. Measurement Methods Statistical Procedures

3.3. The Index of Financial Responsibility

- Qfr1—Do you have an overview of your monthly income (salary, trade income, pension, social benefits)?

- Qfr2—Do you have an overview of the monthly income (payment, income from trade, pension, social benefits) of other household members?

- Qfr3—Do you create a budget and financial plan for your household for a longer period in the future?

- Qfr4—Does your household adhere to the created budget and financial plan for a longer period in the future?

- Qfr5—Do you save any amount per month in the household in case of extraordinary expenses?

- Qfr6—How will you behave in the case of lack of funds?

- Qfr7—If you are saving, please indicate how? (the most progressive ways are valuated as 2, less progressive as 1.5 and no saving as 1)

- Qfr8—Do you have life insurance?

- Qfr9—What would you do if you lose your credit card? (the most secure solutions are valuated as 2, less secure as 1.5 and dangerous as 1)

- Qfr10—How do you store the PIN for the card? (the most secure solutions are valuated as 2, less secure as 1.5 and dangerous as 1)

- Qfr11—Do you read contracts carefully? Do you understand everything before you sign them?

3.4. The Index of Financial Well-Being

- Qfwb1—Do you draw social benefits? (the most valuable answer is ‘no, we are not entitled to them’)

- Qfwb2—Would it be a problem for you if an important appliance (e.g., refrigerator, washing machine) unexpectedly broke down?

- Qfwb3—Do you have a mortgage? To what extent does it burden your household’s budget?

- Qfwb4—Do you have another loan? To what extent does it burden your household’s budget?

- Qfwb5—How often can you go on a family holiday of at least a week in conditions acceptable to you?

- Qfwb6—To what extent will a visit to a cinema or theater of your whole family affect your family budget?

- Qfwb7—How long could your household cover the cost of living if it lost half of its income?

- Qfwb8—How long would your household be able to cover the cost of living with the loss of all income?

- Qfwb9—How do you assess the overall economic situation of your household?

- Qfwb10—Doubled Qfwb9

3.5. The Index of Financial Knowledge

- Qfk1—A new washing machine costs CZK 10,000. The seller offers a 10% discount. How much is the discount?

- Qfk2—What does the term available balance mean?

- Qfk3—What is the difference between credit and debit card?

- Qfk4—What is the difference between interest and credit?

- Qfk5—What does inflation mean? (only a very basic understanding was required)

- Qfk6—What does an overdraft mean?

- Qfk7—When do you use an overdraft? (only very basic understanding is required)

- Qfk8—What does the abbreviation APR mean?

3.6. Coherent Index of Economic Situation

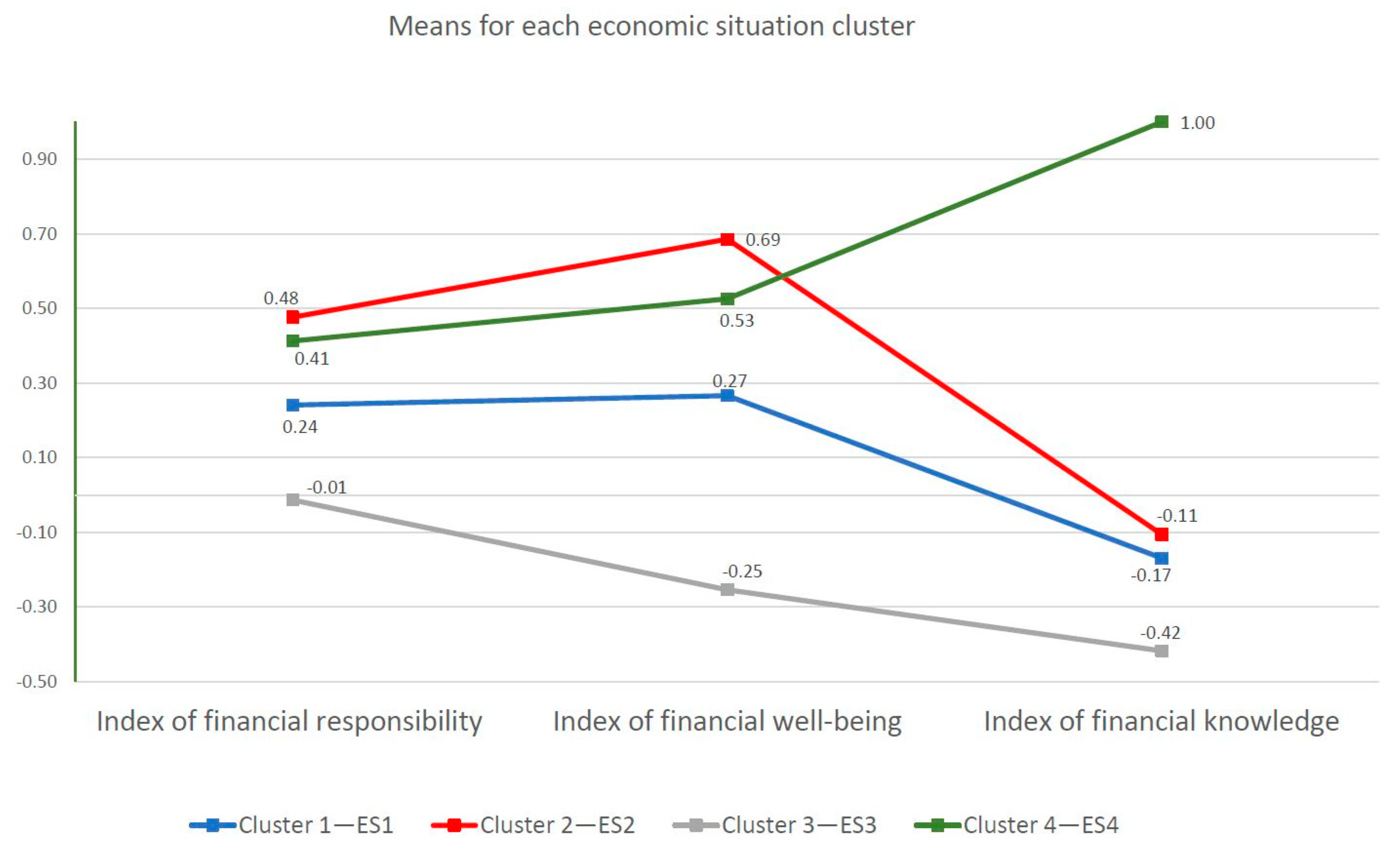

3.7. The Economic Situation Clusters—First Factor of the Model

3.8. Measuring the Values’ Preferences and Factoring the Value Types—Second Factor of the Model

3.9. Assigning the Value Types to Each Individual Respondent

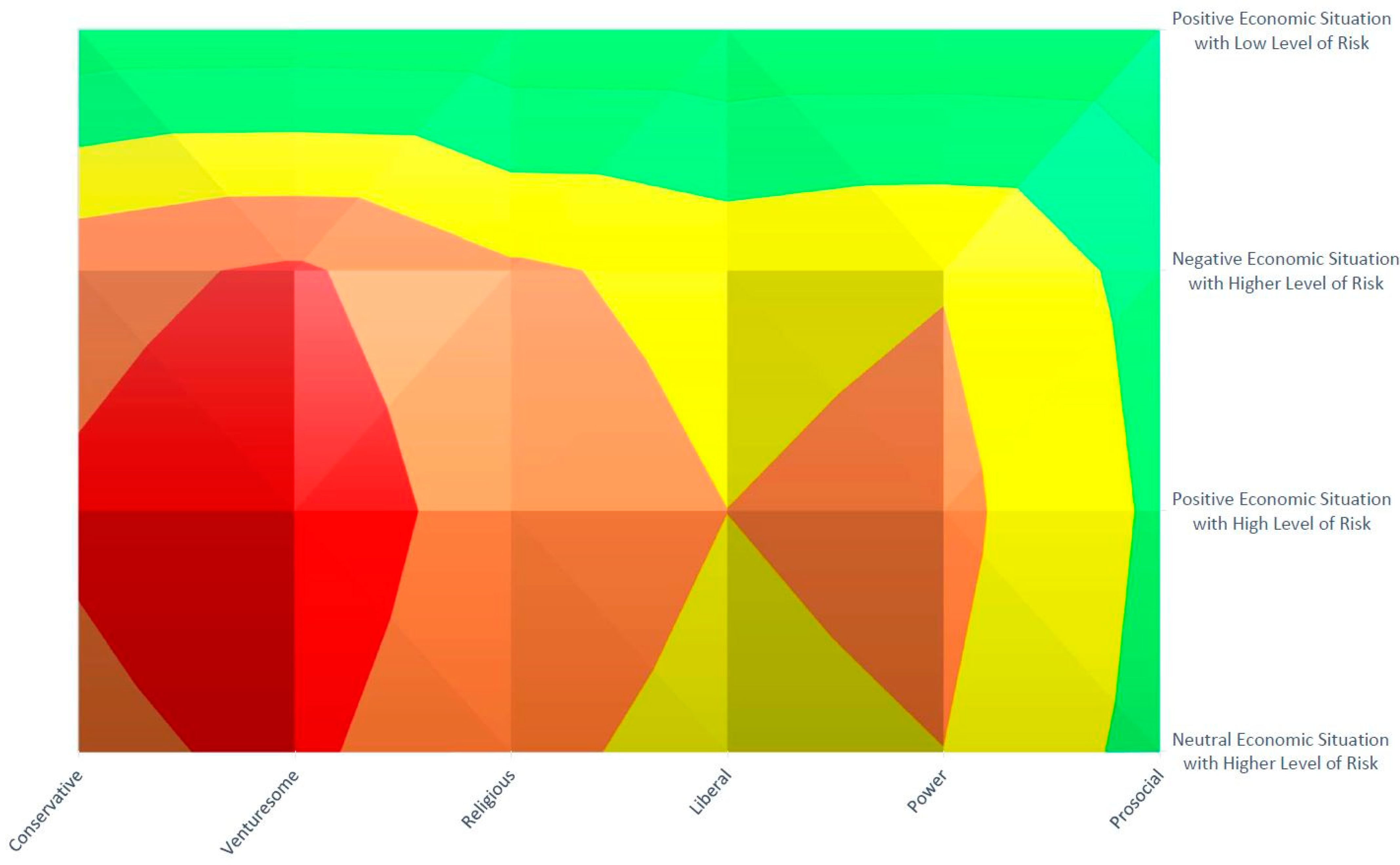

3.10. Hypotheses Testing and Value Types Risk Level

3.11. Risk Level Calculation for Financial Risk Groups

4. Research Results and Construction of the Model

4.1. Categorized Index of Coherent Economic Situation (Ieccat)

4.2. Cluster Analysis Results

4.2.1. Neutral Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk

4.2.2. Positive Economic Situation with High Level of Risk

4.2.3. Negative Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk

4.2.4. Positive Economic Situation with Low Level of Risk

4.2.5. Distribution of Clusters in Population

4.3. Factor Analysis of Values’ Preferences Results

4.4. Hypotheses Testing and Value Types Risk Level

4.5. Crossing Factors and Risk Level Prediction

5. Discussion of Model Application

6. Limits of Study

7. Conclusions

- as a source for development of a diagnostic tool in helping professions

- as a source for development of an auto diagnostic tool in process of self-development

- as a research instrument leading to various hypotheses and to the enhancement of theories concerning economic behaviour.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agresti, Alan. 2007. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics; Hoboken and Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W., Philip Ewart Vernon, and Gardner Lindzey. 1960. Study of Values, 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg, Michael R. 2014. Cluster Analysis for Applications. Burlington: Academic Press/Elsevier Science, Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=931378 (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Arabie, Phipps, Lawrence J. Hubert, and J. Douglas Carroll. 2005. Clustering. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement. Edited by Kimberly Kempf-Leonard. Oxford: Elsevier Academic Press, vol. 1, pp. 317–20. [Google Scholar]

- Arber, Sara, Kirsty Fenn, and Robert Meadows. 2014. Subjective Financial Well-Being, Income and Health Inequalities in Mid and Later Life in Britain. Social Science & Medicine 100: 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azen, Razia, and Cindy M. Walker. 2011. Categorical Data Analysis for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Blazeviciene, Aurelija, and Irayda Jakusovaite. 2007. Value Priorities and Their Relations with Quality of Life in the Baby Boomer Generation of Lithuanian Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Nursing 6: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blue, Levon Ellen, and Peter Grootenboer. 2019. A Praxis Approach to Financial Literacy Education. Journal of Curriculum Studies 51: 755–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-González, Sandra, Sara Fernández-López, Lucía Rey-Ares, and David Rodeiro-Pazos. 2020. The Influence of Attitude to Money on Individuals’ Financial Well-Being. Social Indicators Research 148: 747–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chusmir, Leonard H., Christine S. Koberg, and Joan Mills. 1989. Male-Female Differences in the Association of Managerial Style and Personal Values. The Journal of Social Psychology 129: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, Jeffrey, and Jing Xiao. 2011. The Financial Management Behavior Scale: Development and Validation. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 22: 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, Jeffrey, Luke Dean, Stephen F. Duncan, and Sonya Britt-Lutter. 2020. A Review of Effectiveness Evidence in the Financial-Helping Fields. Family Relations 69: 614–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, Pam Scholder. 1994. Do We Know What We Need to Know? Objective and Subjective Knowledge Effects on pro-Ecological Behaviors. Special Issue: Linking Theory to Policy 30: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESS. 2021. European Social Survey|European Social Survey (ESS). Available online: http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Fan, Lu. 2021. A Conceptual Framework of Financial Advice-Seeking and Short- and Long-Term Financial Behaviors: An Age Comparison. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 42: 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Elizabeth A. 2009. Motivation and Leadership in Social Work Management: A Review of Theories and Related Studies. Administration in Social Work 33: 347–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescu, Andrei. 2020. Why Conservative Values Inherited from Previous Generations Will Continue to Shape Contemporary Identity? Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 19: 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, Jaime R. S. 2013. Clustering in the Field of Social Sciences: That Is Your Choice. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16: 403–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Jodi Jacobson, Deborah Svoboda, Rebecca L. Sander, Philip J. Osteen, Christine Callahan, and Audrey Elkinson. 2015. Evaluation of a Continuing Education Training on Client Financial Capability. Journal of Social Work Education 51: 439–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian. 1984. Many Sides of the Coin: The Psychology of Money Usage. Personality and Individual Differences 5: 501–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grable, John E. 2000. Financial Risk Tolerance and Additional Factors That Affect Risk Taking in Everyday Money Matters. Journal of Business and Psychology 14: 625–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, Ulrike, Yeong-Hyeon Hwang, and Daniel R. Fesenmaier. 2012. Informing Destination Recommender Systems Design and Evaluation through Quantitative Research. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 6: 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2010. Advanced Diagnostics for Multiple Regression: A Supplement to Multivariate Data Analysis. Boston: ScienceOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Hallahan, Terrence A., Robert W. Faff, and Michael D. McKenzie. 2004. An Empirical Investigation of Personal Financial Risk Tolerance. Financial Services Review 13: 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Robert L., and Eri J. Kim. 2012. The Socio-Economic Empowerment Assessment: Addressing Poverty and Economic Distress in Clients. Clinical Social Work Journal 40: 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, Christian, Marina Meila, Fionn Murtagh, and Roberto Rocci. 2015. Handbook of Cluster Analysis. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalmarson, Hanna. 2005. Material Values, Valued Possessions, and Their Use. A Study of School Children Age Nine to Fifteen. E-European Advances in Consumer 7: 333–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, H. Wayne. 1980. German and American Authoritarianism, Self-Estimated Intelligence and Value Priorities. The Journal of Social Psychology 111: 145–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, H. Wayne, and Harsha N. Mookherjee. 1981. Values and Selected Antecedents. The Journal of Social Psychology 113: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, Jeanne M., and Marianne Hilgert. 2002. Financial Knowledge, Experience, and Learning Preferences: Preliminary Results from a New Survey on Financial Literacy. Paper presented at American Council on Consumer Interests 2002 Annual Conference; Available online: https://www.consumerinterests.org/assets/docs/CIA/CIA2002/hogarth-hilgert_financial%20knowledge.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Hung, Angela, Andrew M. Parker, and Joanne Yoong. 2009. Defining and Measuring Financial Literacy, RAND Working Paper Series WR-708. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1498674 (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Inglehart, Ronald. 2015. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 2021. WVS Database. World Values Survey. Project Pages. Available online: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Jacobs-Lawson, Joy M., and Douglas Hershey. 2005. Influence of Future Time Perspective, Financial Knowledge, and Financial Risk Tolerance on Retirement Saving Behaviors. Financial Services Review 14: 331. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Charles S. 1995. The Rokeach Value Survey: Underlying Structure and Multidimensional Scaling. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 129: 583–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jinhee, E. Thomas Garman, and Benoit Sorhaindo. 2003. Relationships among Credit Counseling Clients’ Financial Wellbeing, Financial Behaviors, Financial Stressor Events, and Health. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 14. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Sing. 1988. The Value Orientations of Chinese University Students in Hong Kong. International Journal of Psychology 23: 583–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, Thérèse, Ali Ahmed, Kenny Skagerlund, Camilla Strömbäck, Daniel Västfjäll, and Gustav Tinghög. 2020. Competence, Confidence, and Gender: The Role of Objective and Subjective Financial Knowledge in Household Finance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 41: 626–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lotze, Hermann. 1856. Mikrokosmos. Leipzig: Hirzel, Available online: https://www.zvab.com/buch-suchen/titel/mikrokosmos-3-b%E4nde/autor/lotze/ (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Lusardi, Annamaria. 2012. Numeracy, Financial Literacy, and Financial Decision-Making. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17821 (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Marjanovic, Zdravko, Esther R. Greenglass, Lisa Fiksenbaum, and Chris M. Bell. 2013. Psychometric Evaluation of the Financial Threat Scale (FTS) in the Context of the Great Recession. Journal of Economic Psychology 36: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Loren D., David C. Dollahite, and Jennifer Baumgartner. 2010. In God We Trust: Qualitative Findings on Finances, Family, and Faith From a Diverse Sample of U.S. Families. Family Relations 59: 439–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, Judith, Juanita Shell, and Ralph Steinberg. 1997. Values of Postpartum Women from the Inner City: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Child and Family Studies 6: 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzingiri, Calvin, John W. Muteba Mwamba, and Jacobus Nicolaas Keyser. 2018. Incentivized Time Preferences, Level of Education in a Household and Financial Literacy: Laboratory Evidence. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musil, Bojan, Velko S. Rus, and Janek Musek. 2009. The Rokeach Value Survey in Comparative Study of Japanese and Slovenian Students: Towards the Underlying Structure. Studia Psychologica 51: 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad, Mohammad G., and Katayon Javid. 2018. Subjective and Objective Financial Literacy, Opinion Leadership, and the Use of Retail Banking Services. International Journal of Bank Marketing 36: 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, Richard G., Dee Warmath, Daniel Fernandes, and John G. Lynch Jr. 2018. How Am I Doing? Perceived Financial Well-Being, Its Potential Antecedents, and Its Relation to Overall Well-Being. Journal of Consumer Research 45: 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2013. OECD Framework for Statistics on the Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ouachani, Sonia, Olfa Belhassine, and Aïda Kammoun. 2021. Measuring Financial Literacy: A Literature Review. Managerial Finance 47: 266–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Ji Eun, Jun Yu, and Joyce Xin Zhou. 2010. Consumer Innovativeness and Shopping Styles. Journal of Consumer Marketing 27: 437–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapkin, Bruce D., and Douglas A. Luke. 1993. Cluster Analysis in Community Research: Epistemology and Practice. American Journal of Community Psychology 21: 247–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, David L. 2010. Financial Literacy Explicated: The Case for a Clearer Definition in an Increasingly Complex Economy. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, Marsha. 1994. Special Possessions and the Expression of Material Values. Journal of Consumer Research 21: 522–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, Marsha. 1999. Material Values. In The Elgar Companion to Consumer Research and Economic Psychology. Northampton: Elgar, pp. 374–80. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, Marsha. 2004. The Material Values Scale: A Re-Inquiry into Its Measurement Properties and the Development of a Short Form. Journal of Consumer Research 31: 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, Marsha, and Scott Dawson. 1992. A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1968. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values: A Theory of Organization and Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Royse, David, Michele Staton-Tindall, Karen Badger, and J. Matthew Webster. 2009. Needs Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195368789. [Google Scholar]

- Sauve, Andre Lemieux G. 1999. Values of Senior Citizens Enrolled in a University Curricula Versus Those Who Are Not. Educational Gerontology 25: 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomerus, Georg, and Matthias C. Angermeyer. 2021. Blind Spots in Stigma Research? Broadening Our Perspective on Mental Illness Stigma by Exploring “What Matters Most” in Modern Western Societies. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 30: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1992. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego: Academic Press, vol. 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2005. Robustness and Fruitfulness of a Theory of Universals in Individual Values. In Valores e Trabalho (Values and Work). Edited by A. Tamayo and J. Porto. Brasilia: Editora Universidade de Brasilia. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Wolfgang Bilsky. 1987. Toward a Universal Psychological Structure of Human Values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53: 550–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Wolfgang Bilsky. 1990. Toward a Theory of the Universal Content and Structure of Values: Extensions and Cross-Cultural Replications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58: 878–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheskin, David. 2011. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures, 5th ed. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M. Joseph. 2018. The Psychology of Material Well-Being. Applied Research in Quality of Life: The Official Journal of the International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies 13: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Survey Project. 2018. Online. Olomouc: ITTS s.r.o. Available online: https://www.socialsurvey.eu/ (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Song, Yongming, and Yi Peng. 2019. A MCDM-Based Evaluation Approach for Imbalanced Classification Methods in Financial Risk Prediction. IEEE Access 7: 84897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, Eduard. 1921. Lebensformen. Geisteswissenschaftliche Psychologie und Ethik der Persönlichkeit. Halle: M. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck, Camilla, Thérèse Lind, Kenny Skagerlund, Daniel Västfjäll, and Gustav Tinghög. 2017. Does Self-Control Predict Financial Behavior and Financial Well-Being? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 14: 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taagepera, Rein. 2008. Making Social Sciences More Scientific: The Need for Predictive Models. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, Marzieh, Zare Hosein, and Seyyed Mehrizi. 2013. The Relation between Financial Literacy, Financial Wellbeing and Financial Concerns. International Journal of Business and Management 8: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tahiri Jouti, Ahmed. 2018. Islamic Finance: Financial Inclusion or Migration? ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance 10: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, Thomas Li-ping. 1992. The Meaning of Money Revisited. Journal of Organizational Behavior 13: 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Mark. 2011. Measuring Financial Capability and Its Determinants Using Survey Data. Social Indicators Research 102: 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaculík, Martin, Jakub Procházka, and Petr Kveton. 2007. The Relation Between Prosocial Behavior and Demanding Prosocial Behavior. Studia Psychologica 49: 157–66. [Google Scholar]

- van Raaij, W. Fred. 2016. Responsible Financial Behavior. In Understanding Consumer Financial Behavior: Money Management in an Age of Financial Illiteracy. Edited by W. Fred van Raaij. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 127–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mises, Ludwig. 1998. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Alabama: The Ludwig von Mises Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Vural, Gamze, and Aichetou Beichar. 2020. The Relationship between Financial Literacy and Individual Financial Decisions: An Explaratory Study. Finansal Okuryazarlik ve Bireysel Finansal Kararlar Arasindaki Ilişki Üzerine Keşifsel Bir Çalişma 29: 243–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Minfang. 2020. Financial Risk Prediction Model of International Trade Enterprises of Marine Transportation. Journal of Coastal Research 103: 173–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Oliver J., and Stephen E. Satchell. 2011. Social Welfare Issues of Financial Literacy and Their Implications for Regulation. Journal of Regulatory Economics 40: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Jing J., M. J. Alhabeeb, Gong-Soog Hong, and George W. Haynes. 2001. Attitude toward Risk and Risk-Taking Behavior of Business-Owning Families. Journal of Consumer Affairs 35: 307–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Jing Jian, Cheng Chen, and Fuzhong Chen. 2014. Consumer Financial Capability and Financial Satisfaction. Social Indicators Research 118: 415–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Kent T., and Donald J. Templer. 1982. The Development of a Money Attitude Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 46: 522–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Rui, Deanna L. Sharpe, and Feifei Wang. 2011. Decomposing the Age Effect on Risk Tolerance. The Journal of Socio-Economics 40: 879–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeh, Hsiang-Yuan, Yu-Ching Yeh, and Da-Bai Shen. 2020. Word Vector Models Approach to Text Regression of Financial Risk Prediction. Symmetry 12: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zatloukal, Leoš, Miloš Havlík, Zdislav Doleček, and Jaroslav Šotola. 2011. Komplexní Posuzování Potřeb Klientů v Rámci Poradenského Rozhovoru z Hlediska Přístupu Zaměřeného Na Řešení. Sociální Práce: =Sociálna Práca: Odborná Revue pro Sociální Práci 11: 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Jing. 2020. Corporate Financial Risk Prediction Based on Embedded System and Deep Learning. Microprocessors and Microsystems. January. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S0141933120305627&authtype=shib&lang=cs&site=eds-live&scope=site&authtype=shib&custid=s7108593 (accessed on 16 May 2021).

| Ieccat | Definition | n | f | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iec < μ − σ | 515 | 0.1367 | 515 |

| 2 | μ − σ ≤ Iec < μ | 1240 | 0.3291 | 1755 |

| 3 | μ ≤ Iec < μ + σ | 1237 | 0.3283 | 2992 |

| 4 | μ + σ ≤ Iec | 776 | 0.2059 | 3768 |

| Cluster 1—ES1 Neutral Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk | Cluster 2—ES2 Positive Economic Situation with High Level of Risk | Cluster 3—ES3 Negative Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk | Cluster 4—ES4 Positive Economic Situation with Low Level of Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ifr | 0.240723 | 0.476966 | −0.013202 | 0.412660 |

| Ifwb | 0.266023 | 0.685856 | −0.253836 | 0.525914 |

| Ifk | −0.168730 | −0.105332 | −0.416910 | 1.000000 |

| Risk level ESr | 0.597 | 0.657 | 0.588 | 0.056 |

| Respondents Clustered by the Economic Situation | n | % | c | ESr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES1 Neutral economic situation with higher level of risk | 1099 | 29.17% | 1099 | 0.597 |

| ES2 Positive economic situation with high level of risk | 1031 | 27.36% | 2130 | 0.657 |

| ES3 Negative economic situation with higher level of risk | 411 | 10.91% | 2541 | 0.588 |

| ES4 Positive economic situation with low level of risk | 1227 | 32.56% | 3768 | 0.056 |

| Total | 3768 | 100.00% |

| Value Preferences (Mixed Terminal and Instrumental) | Value Types | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VT1 CONSERVA-TIVE | VT2 VENTURE-SOME | VT3 RELIGIOUS | VT4 LIBERAL | VT5 POWER | VT6 PROSOCIAL | |

| VP1—True friendship | 0.642508 | |||||

| VP2—Love | 0.646906 | |||||

| VP3—Wisdom | 0.558671 | |||||

| VP4—Helpful | 0.677536 | |||||

| VP5—Pleasure | 0.670108 | |||||

| VP6—Equal opportunity of all | 0.634111 | |||||

| VP7—Self-respect | 0.583479 | |||||

| VP8—Social recognition | 0.588818 | |||||

| VP9—World of beauty | 0.532125 | |||||

| VP10—Freedom | 0.584544 | |||||

| VP11—Happiness | 0.504324 | |||||

| VP12—Eternal life | 0.848416 | |||||

| VP13—Inner harmony | 0.502199 | |||||

| VP14—Exciting life | 0.762913 | |||||

| VP15—Economic prosperity | ||||||

| VP16—Independent | 0.542398 | |||||

| VP17—Responsible | 0.601934 | |||||

| VP18—Assertive | 0.585795 | |||||

| VP19—Open minded | 0.671969 | |||||

| VP20—Self-control | 0.540978 | |||||

| VP21—Capable | ||||||

| VP22—Faith | 0.838601 | |||||

| VP23—Polite | 0.541606 | |||||

| VP24—Intellectual | 0.483877 | |||||

| VP25—Ambitious | 0.603383 | |||||

| VP26—Authoritative (socially powered) | 0.660592 | |||||

| VP27—Enjoying life | 0.754728 | |||||

| VP28—Courageous | 0.715958 | |||||

| VP29—Creative | 0.583571 | |||||

| VP30—Obedient | 0.543216 | |||||

| VP31—Clean | ||||||

| VP32—Respect for parents and the elderly | 0.590510 | |||||

| VP33—National security | 0.599107 | |||||

| VP34—Family security | 0.612122 | |||||

| VP35—Acceptance, belongingness | ||||||

| VP36—Health | 0.632394 | |||||

| Value Type | n | f | c |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONSERVATIVE | 1339 | 35.54% | 1339 |

| VENTURESOME | 199 | 5.28% | 1538 |

| RELIGIOUS | 308 | 8.17% | 1846 |

| LIBERAL | 136 | 3.61% | 1982 |

| POWER | 33 | 0.88% | 2015 |

| PROSOCIAL | 1753 | 46.52% | 3768 |

| Total | 3768 | 100.00% |

| Value Type | Economic Situation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk | Positive Economic Situation with High Level of Risk | Negative Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk | Positive Economic Situation with Low Level of Risk | |

| PVT1 CONSERVATIVE | 406 10.77% z: 1.1576 | 357 9.47% z: −0.7159 | 169 4.49% z: 2.5055 * | 407 10.80% z: −2.1084 * |

| PVT2 VENTURESOME | 44 1.17% z: −2.2502 * | 76 2.02% z: 3.5208 *** | 33 0.88% z: 2.6388 ** | 46 1.22% z: −2.9224 ** |

| PVT3 RELIGIOUS | 91 2.42% z: 0.1526 | 70 1.86% z: −1.9040 | 54 1.43% z: 3.8921 *** | 93 2.47% z: −0.9258 |

| PVT4 LIBERAL | 34 0.90% z: −1.0889 | 35 0.93% z: −0.4334 | 15 0.40% z: 0.0464 | 52 1.38% z: 1.4376 |

| PVT5 POWER | 7 0.19% z: −1.0098 | 5 0.13% z: −1.5803 | 8 0.21% z: 2.4681 * | 13 0.35% z: 0.8410 |

| PVT6 PROSOCIAL | 517 13.72% z: 0.4102 | 488 12.95% z: 0.6113 | 132 3.50% z: −6.2036 *** | 616 16.35% z: 3.1474 ** |

| Value Type (PVT) | Categorized Coherent Index of Economic Situation (Ieccat) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Iec ≤ μ − σ | 2 μ − σ < Iec ≤ μ | 3 μ < Iec ≤ μ + σ | 4 μ + σ ≤ Iec | |

| PVT1 CONSERVATIVE | 206 5.47% z: 2.2779 * | 456 12.10% z: 1.1121 | 420 11.15% z: −1.4193 | 257 6.82% z: −1.5790 |

| PVT2 VENTURESOME | 45 1.19% z: 3.7746 *** | 76 2.02% z: 1.6294 | 50 1.33% z: −2.3778 * | 28 0.74% z: −2.3385 * |

| PVT3 RELIGIOUS | 62 1.65% z: 3.4454 *** | 84 2.23% z: −2.1967 * | 109 2.89% z: 0.9986 | 53 1.41% z: −1.5338 |

| PVT4 LIBERAL | 19 0.50% z: 0.1047 | 39 1.04% z: −1.0699 | 45 1.19% z: 0.0655 | 33 0.88% z: 1.0781 |

| PVT5 POWER | 8 0.21% z: 1.7762 | 7 0.19% z: −1.4363 | 9 0.24% z: −0.6827 | 9 0.24% z: 0.9528 |

| PVT6 PROSOCIAL | 175 4.64% z: −6.1418 *** | 578 15.34% z: 0.0772 | 604 16.03% z: 1.9826 * | 396 10.51% z: 2.8251 ** |

| Personal Value Type (PVT) | PVTinfl | Economic Situation (ESr) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk 59.7% | Positive Economic Situation with High Level of Risk 65.71% | Negative Economic Situation with Higher Level of Risk 58.82% | Positive Economic Situation with Low Level of Risk 5.66% | ||

| PVT1 CONSERVATIVE | 1.2600 | 75.23% | 82.80% | 74.11% | 7.14% |

| PVT2 VENTURESOME | 1.4119 | 84.30% | 92.78% | 83.04% | 8.00% |

| PVT3 RELIGIOUS | 1.0726 | 64.04% | 70.48% | 63.08% | 6.07% |

| PVT4 LIBERAL | 0.9142 | 54.58% | 60.07% | 53.77% | 5.18% |

| PVT5 POWER | 1.0028 | 59.87% | 65.90% | 58.98% | 5.68% |

| PVT6 PROSOCIAL | 0.5574 | 33.28% | 36.63% | 32.79% | 3.16% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pospíšil, J.; Matulayová, N.; Macháčková, P.; Jurníčková, P.; Olecká, I.; Pospíšilová, H. Value-Based Financial Risk Prediction Model. Risks 2021, 9, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9110205

Pospíšil J, Matulayová N, Macháčková P, Jurníčková P, Olecká I, Pospíšilová H. Value-Based Financial Risk Prediction Model. Risks. 2021; 9(11):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9110205

Chicago/Turabian StylePospíšil, Jiří, Nataša Matulayová, Pavla Macháčková, Pavlína Jurníčková, Ivana Olecká, and Helena Pospíšilová. 2021. "Value-Based Financial Risk Prediction Model" Risks 9, no. 11: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9110205

APA StylePospíšil, J., Matulayová, N., Macháčková, P., Jurníčková, P., Olecká, I., & Pospíšilová, H. (2021). Value-Based Financial Risk Prediction Model. Risks, 9(11), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9110205