Determinants of Demand for Private Long-Term Care Insurance (Empirical Evidence from Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Demand for LTCI: Theoretical Background

3. Research Goal and Data Acquisition Method

- Material situation: we checked if people who are positively or negatively assessing their level of wealth were more interested in purchasing LTCI. Theoretically, people with low material status should be more eager to secure their future because in their case it would be particularly difficult to pay for care in old age. On the other hand, wealthy people have the greatest opportunities to save for private care, and they can also have a relatively high level of insurance awareness.

- Possession of offspring: we checked whether the childfree or the parents were more interested in purchasing LTCI. On the one hand, numerous offspring can be a demotivating factor for LTCI purchases, because children can be seen as a natural substitute for old age care; on the other hand, it can be a motivating factor for buying LTCI, as insurance protects against loss of relatives and also protects the parents from becoming a burden for the children in old age.

- Gender: we checked if men or women were more interested in purchasing LTCI. It may seem that, according to the principle of negative selection, LTCI should be more readily acquired by women, because due to the longer life expectancy, they are more burdened with the risk of dependence, and thus higher costs of long-term care. Men not only die sooner, but they are more likely to receive informal care provided by their life partners (wives).

- Age: we checked if people in early or late adulthood were more interested in purchasing LTCI. According to the idea of care insurance, it is more cost-effective the sooner it is purchased. However, it can be presumed that in the face of budget restrictions and the need to finance other (more urgent) things, the desire to purchase such a product appears only in the period of late adulthood or even early old age.

- Place of residence: we checked how the place of residence is related to the willingness to purchase LTCI, and whether the inhabitants of cities or small towns and villages showed greater interest in this product. Theoretically, natural forms of care are more developed in villages, based on traditional family roles and neighborly assistance, while in large agglomerations, formal (paid-for) support is more often employed, due to the lower ability and inclination to provide traditional care by relatives.

- Professional status: we checked whether the fact of having or not having a job was related to the propensity to buy LTCI. Presumably, working people generally show a higher level of resourcefulness than non-working people, and therefore also a higher propensity to protect themselves in the event of various life events, including dependence. On the other hand, the lack of a job should additionally stimulate the person (apart from the issue of budgetary constraints) to secure themselves for the future.

- Education: we checked whether the level of education was related to the propensity to buy LTCI. We assumed that the higher the level of education, the greater the awareness of various problems and threats, and thus the greater concern for own well-being. It also means greater financial literacy, which provides qualifications for rational household budget management and obtaining funds for the purchase of insurance.

- Risk awareness: we checked whether the various factors that shape awareness of dependence risk and the costs associated with it had an impact on the propensity to buy LTCI. These factors are as follows: the presence in the immediate environment of the dependent person, experience with formal care (whether the dependent person who is in the environment uses paid care), and knowledge about the costs of long-term care. We assumed that the greater the risk awareness (contact with dependent persons, experience with formal care, and understanding of the costs of this care), the greater the desire to acquire LTCI.

- Preferences regarding the method of financing long-term care: we checked whether the preferences were related to the willingness to purchase LTCI. We assumed that people advocating individual financing of care are more likely to buy insurance than people advocating other financing methods.

- Individual foresight: we checked whether the general propensity to protect oneself against different risks affected the desire to purchase LTCI. It can be assumed that people who are generally more prudent about life will also be more willing to protect themselves in the event of dependence.

- Health status: we checked if people who are positive or negative about their psychophysical condition were more interested in purchasing LTCI. It is likely that the most willing to buy will be the “limons”, or people who in their own opinion are the most exposed to the risk of dependence. These people, due to poor health, will be more often forced to use the help of others in the future.

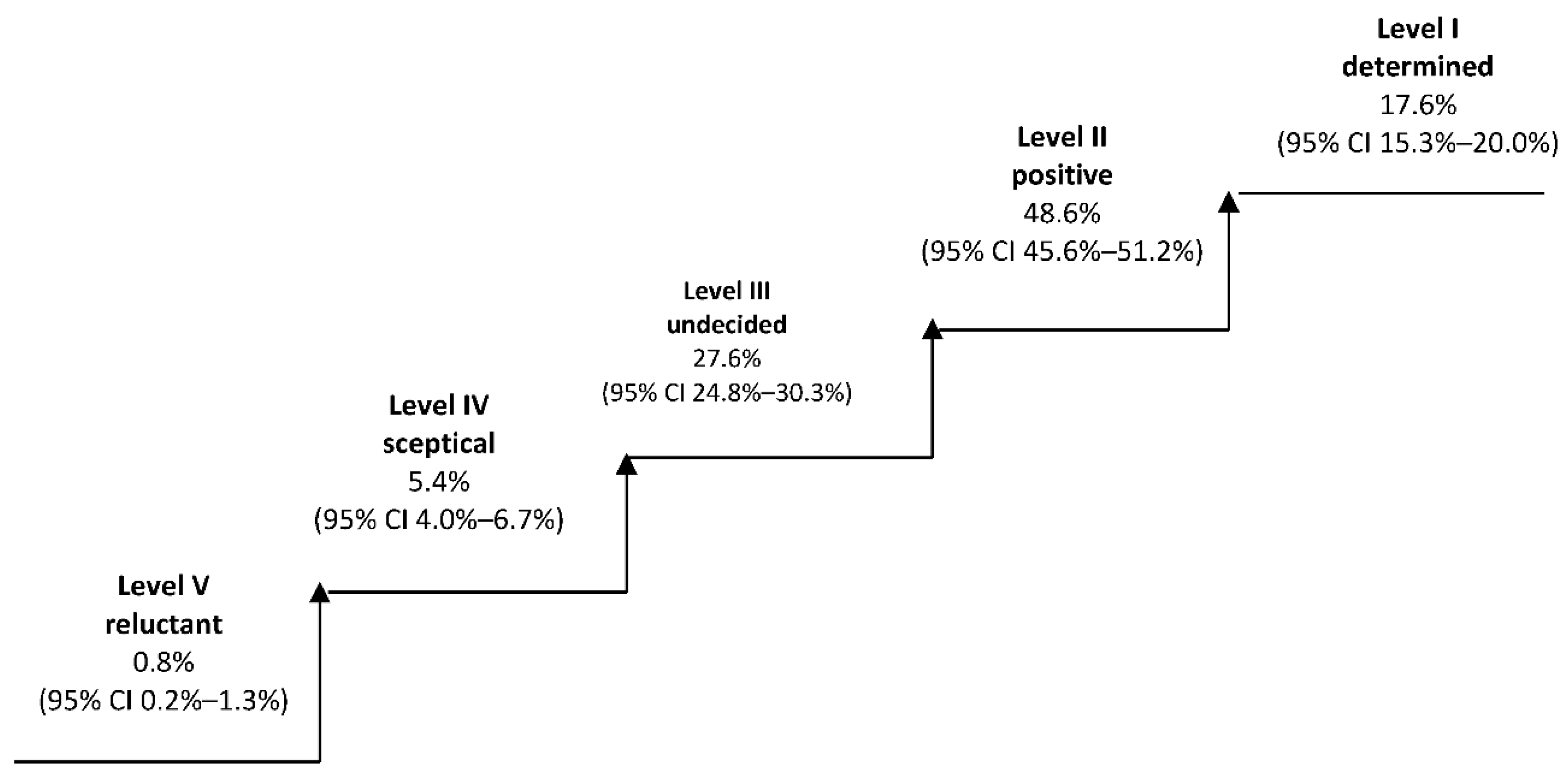

4. The Demand for LTCI in Poland in the Light of Empirical Research

5. Determinants of LTCI Demand in Poland

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akerlof, George A. 1970. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 3: 175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, W. Peter, Lawrence J. Gitman, Khurshid Ahmad, and M. Fall Ainina. 1989. Long-term catastrophic care: A financial planning perspective. Journal of Risk and Insurance 1: 146–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Nicholas. 2010. Long-term care: A suitable case for social insurance. Social Policy & Administration 44: 359–74. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, Martin, Philippe De Donder, Claude Fluet, Marie-Louise Leroux, and Pierre-Carl Michaud. 2019. Long-term care risk misperceptions. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice 44: 183–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. Jeffrey, and Amy Finkelstein. 2007. Why is the market for long-term care insurance so small? Journal of Public Economics 91: 1967–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. Jeffrey, and Amy Finkelstein. 2008. The Interaction of public and private insurance: Medicaid and the long-term care insurance market. American Economic Review 98: 1083–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. Jeffrey, and Amy Finkelstein. 2009. The private market for long-term care insurance in the United States: A review of the evidence. Journal of Risk Insurance 76: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Herrera, Adelina, Rebeca Butterfield, Jose-Luis Fernandez, Raphael Wittenberg, and Joshua M. Wiener. 2012. Barriers and Opportunities for Private Long-Term Care Insurance in England: What Can We Learn from other Countries. PSSRU Discussion Paper, nr 2780. London: Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Font, Joan, and Christophe Courbage. 2011. Financing Long-Term Care in Europe. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmilla. [Google Scholar]

- Courbage, Christophe, and Nolwenn Roudaut. 2008. Empirical evidence on long-term care insurance purchase in France. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurances-Issues and Practice 4: 645–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, Helmuth, Pierre Pestieau, and Gregory Ponthiere. 2012. The economics of long-term care: A survey. Nordic Economic Policy Review 2: 107–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, David, and Richard Zeckhauser. 1998. Adverse selection in health insurance. Forum for Health Economics & Policy 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- De Donder, Philippe, and Marie-Louise Leroux. 2013. Behavioral Biases and Long-Term Care Insurance: A Political Economy Approach. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 14: 551–75. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelsteinm, Amy, and Kathleen McGarry. 2006. Multiple dimensions of private information: Evidence from the long-term care insurance market. American Economic Review 4: 938–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakouris, Konstantinos. 2008. Ageing characterises the demographic perspectives of the European societies. Eurostat Statistics in Focus 72: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- He, Alex Jingwei, Jiwei Qian, Wai-sum Chan, and Kee-lee Chou. 2020. Preferences for private long-term care insurance products in a super-ageing society: A discrete choice experiment in Hong-Kong. Social Science & Medicine 270: 113632. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Martín, Sergi, José M. Labeaga-Azcona, and Cristina Vilaplana-Prieto. 2016. Interactions between Private Health and Long-term Care Insurance and the Effects of the Crisis: Evidence for Spain. Health Economics 25: 159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2013. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Denis. 2008. The long-term care insurance market. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurances-Issues and Practice 1: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimaviciute, Jusitina. 2020. Long-term care and myopic couples. International Tax and Public Finance 27: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambregts, Timo R., and Frederik T. Schut. 2019. A Systematic Review of the Reasons for Low Uptake of Long-Term Care Insurance and Life Annuities: Could Integrated Products Counter Them? Netspar Survey Paper no. 55, Network for Studies on Pensions, Aging and Retirement. Available online: https://www.netspar.nl/assets/uploads/P20190822_SUR55_Lambregts.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Lin, Hazhen, and Jeffrey T. Prince. 2016. Determinants of Private Long-Term Care Insurance Purchase in Response to the Partnership Program. Health Services Research 51: 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, Brian E., Helena Temkin-Greener, Benjamin P. Chapman, David C. Grabowski, and Yue Li. 2016. The Impact of Consumer Numeracy on the Purchase of Long-Term Care Insurance. Health Services Research 51: 1612–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2011. Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, Mark. 1990. The Rational Non-Purchase of Long-Term Care Insurance. Journal of Political Economy 98: 153–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalon, William J. 1992. Possible Reforms for Financing Long-Term Care. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 3: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schernberg, Helene. 2019. Long-Term Care Insurance Purchase under Time-Inconsistent Risk Attitudes. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3418316 (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Shefrin, Hersh, and Richard Thaler. 1988. The behavioral live-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry 26: 609–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Herbert A. 1972. Theories of bounded rationality. Decisions and Organization 1: 161–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Frank A., and Edward C. Norton. 1997. Adverse Selection, Bequests, Crowding Out, and Private Demand for Insurance: Evidence from the Long-Term Care Insurance Market. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 15: 201–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więckowska, Barabara. 2010. Ubezpieczenie w zarządzaniu ryzykiem niedołęstwa starczego. In Społeczne Aspekty Rynku Ubezpieczeniowego. Edited by Tadeusz Szumlicz. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH, pp. 209–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wolańska, Wioletta, and Łukasz Jurek. 2018. Preferencje wobec sposobu finansowania opieki długoterminowej w Polsce. Ubezpieczenia Społeczne. Teoria i Praktyka 3: 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou-Richter, Tian, Mark J. Browne, and Helmut Gründl. 2010. Don’t they care? Or, are they just unaware? Risk perception and the demand for long-term care insurance. The Journal of Risk and Insurance 4: 715–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweifel, Peter, and Wolfram Strüwe. 1998. Long-Term Care Insurance in a Two-Generation Model. Journal of Risk and Insurance 65: 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | According to Brown and Finkelstein (2007), prices of LTCI are marked up substantially above actuarially fair levels. They estimated that load factor is much larger than, e.g., for standard health insurance, which indicates the existence of supply-side market failures. |

| 2 | LTCI does not have to be purchased only for oneself. It may be purchased also for someone else (for example, by children for their parents) to secure against potential burden. In this research, however, we focused only on self-protection option. |

| 3 | The provided interpretations relate to the included set of explanatory variables of the model and the assumption of ceteris paribus. This means that we compared people who have identical values of explanatory variables except for the one at which the parameter is interpreted. |

| Attribute | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 467 | 45.52 |

| Male | 559 | 54.48 | |

| Age | 40–49 | 442 | 43.08 |

| 50–59 | 359 | 34.99 | |

| 60–69 | 225 | 21.93 | |

| Place of residence | Village | 407 | 39.67 |

| Town | 306 | 29.82 | |

| City | 313 | 30.51 | |

| Education | Primary or incomplete primary | 11 | 1.07 |

| Secondary, basic vocational, post-secondary | 605 | 58.97 | |

| Higher | 410 | 39.96 | |

| Subjective assessment of the material situation | I can afford everything I need and I’m still able to save money | 329 | 32.07 |

| I can afford everything I need, but I don’t save | 74 | 7.21 | |

| I live sparingly, that’s why I can afford everything I need | 467 | 45.52 | |

| I can only afford basic expenses | 145 | 14.13 | |

| I can’t afford basic expenses | 11 | 1.07 | |

| Subjective health assessment | Very good | 258 | 25.15 |

| Good | 581 | 56.63 | |

| Average | 160 | 15.59 | |

| Bad | 22 | 2.14 | |

| Very bad | 5 | 0.49 | |

| Children | None | 101 | 9.84 |

| One, two | 679 | 66.18 | |

| Three and more | 246 | 23.98 | |

| Professional status | Active | 743 | 72.42 |

| Inactive | 283 | 27.58 | |

| Region | Central | 209 | 20.37 |

| Southern | 211 | 20.57 | |

| Eastern | 179 | 17.45 | |

| North-western | 244 | 23.78 | |

| South-western | 27 | 2.63 | |

| Northern | 156 | 15.20 | |

| A person in need of care | Yes | 671 | 65.40 |

| No | 355 | 34.60 | |

| Tendency to secure own future | 1 low | 46 | 4.48 |

| 2 | 171 | 16.67 | |

| 3 | 460 | 44.83 | |

| 4 | 282 | 27.49 | |

| 5 high | 67 | 6.53 | |

| Experience with a formal caregiver | There was a formal caregiver | 191 | 18.62 |

| There was no formal caregiver | 480 | 46.78 | |

| Knowledge about LTC costs | 1 low | 56 | 5.46 |

| 2 | 301 | 29.34 | |

| 3 | 413 | 40.25 | |

| 4 | 208 | 20.27 | |

| 5 high | 48 | 4.68 | |

| Financing preferences | Individual | 239 | 23.29 |

| Other | 787 | 76.71 |

| Attribute | Category | Level of Interest in Purchasing LTCI | Cramer’s V p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interested (“Definitely Yes” and “Rather Yes”) | Others (“Rather Not”, “Definitely Not” and “I Don’t Know”) | ||||

| Gender | Female | 65.5 | 34.5 | 0.015 | |

| Male | 66.9 | 33.1 | 0.640 | ||

| Age | 40–49 | 64.9 | 35.1 | 0.026 | |

| 50–59 | 67.7 | 32.3 | 0.707 | ||

| 60–69 | 66.7 | 33.3 | |||

| Place of residence | Village | 64.6 | 35.4 | 0.095 ** | |

| Town | 61.8 | 38.2 | 0.009 | ||

| City | 72.8 | 27.2 | |||

| Education | Primary or incomplete primary | 63.6 | 36.4 | 0.258 *** | |

| Secondary, basic vocational, postsecondary | 56.2 | 43.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Higher | 81.2 | 18.8 | |||

| Subjective assessment of the material situation | I can afford everything I need and I’m still able to save money | 83.6 | 16.4 | 0.291 *** | |

| I can afford everything I need, but I don’t save | 73.0 | 27.0 | <0.001 | ||

| I live sparingly, that’s why I can afford everything I need | 60.4 | 39.6 | |||

| I can only afford basic expenses | 44.8 | 55.2 | |||

| I can’t afford basic expenses | 36.4 | 63.6 | |||

| Subjective health assessment | Very good | 40.0 | 60.0 | 0.125 ** | |

| Good | 72.7 | 27.3 | 0.003 | ||

| Average | 60.6 | 39.4 | |||

| Bad | 63.7 | 36.3 | |||

| Very bad | 75.6 | 24.4 | |||

| Children | None | 62.4 | 37.6 | 0.068 | |

| One, two | 67.9 | 32.1 | 0.322 | ||

| Three and more | 63.4 | 36.6 | |||

| Professional status | Active | 67.7 | 32.3 | 0.049 | |

| Inactive | 62.5 | 37.5 | 0.119 | ||

| Experience with a person requiring care | No | 63.1 | 36.9 | 0.0490.117 | |

| Yes | There was a formal caregiver | 85.3 | 14.7 | 0.193 *** | |

| There was no formal caregiver | 61.0 | 39.0 | <0.001 | ||

| Tendency to secure own future | 1 low | 30.4 | 69.6 | 0.465 *** | |

| 2 | 36.8 | 63.2 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 | 59.8 | 40.2 | |||

| 4 | 92.9 | 7.1 | |||

| 5 high | 98.5 | 1.5 | |||

| Knowledge about LTC costs | 1 low | 35.7 | 64.3 | 0.344 *** | |

| 2 | 47.5 | 52.5 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 | 68.5 | 31.5 | |||

| 4 | 91.3 | 8.7 | |||

| 5 high | 91.7 | 8.3 | |||

| Financing preferences | Individual | 91.6 | 8.4 | 0.375 *** | |

| Other | 58.6 | 41.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Gender | categorical variable with a value of 1 for men and 0 for women |

| Age | ordinal 3-state variable, for which two 0–1 variables were introduced, taking people aged 40–49 as reference variable |

| Place of residence | ordinal 3-state variable, for which two 0–1 variables were introduced, taking cities as the reference variable |

| Education | ordinal 2-state variable with the value 1 for higher education and 0 for lower than higher education |

| Subjective assessment of the material situation | ordinal 5-state variable, for which four 0–1 variables were introduced, taking “I can’t afford basic expenses” as reference variable |

| Subjective health assessment | ordinal 5-state variable, for which four 0–1 variables were introduced, taking “very bad” as reference variable |

| Children | nominal variable with a value of 0 for people with children and 1 for people without children |

| Professional status | nominal variable with a value of 1 for working people and 0 for non-working people |

| Presence of dependent person | nominal variable with a value of 1 for people who have someone in their environment who is dependent and requires care, and 0 for people who do not have someone like that in their environment |

| Experience with formal care | nominal variable with a value of 1 if the formal caregiver participated in the care process for the dependent person and 0 if the services of a formal caregiver were not used |

| Individual foresight | ordinal 5-state variable, for which four 0–1 variables were introduced, taking “1 low” as reference variable |

| Knowledge of LTC costs | ordinal 5-state variable, for which four 0–1 variables were introduced, taking “1 low” as reference variable |

| Preference for LTC financing | nominal variable with a value of 1 if the respondent believes that everyone should bear the costs of their own formal care and 0 for other opinions |

| Variable | Parameter B | p-Value | Odds Ratio Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.990 | 0.0000 | |

| Individual foresight | |||

| 1 low-ref. | |||

| 3 | 0.608 *** | 0.0008 | 1.838 |

| 4 | 2.227 *** | 0.0000 | 9.272 |

| 5 high | 3.599 *** | 0.0005 | 36.555 |

| Knowledge about the cost of care | |||

| 1 low-ref | |||

| 3 | 0.647 *** | 0.0001 | 1.910 |

| 4 | 1.482 *** | 0.0000 | 4.404 |

| 5 high | 1.350 * | 0.0229 | 3.857 |

| Preferences for LTC financing | 0.895 ** | 0.0011 | 2.448 |

| Education | 0.652 *** | 0.0002 | 1.920 |

| Children | −0.630 * | 0.0318 | 0.533 |

| Goodness of fit statistics: | |||

| Likelihood ratio (9) = 329.8, p < 0.001 | |||

| Hosmer Lemeshow = 3.5202, p = 0.7413 | |||

| % correct predictions = 74.2% | |||

| Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.381 | |||

| Knowledge of LTCI Costs | Tendency to Secureown Future | Age | Education | Place of Residence | Financing Formal Care | Person Requiring Formal Care | Experience with a Formal Caregiver | Financial Situation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| knowledge of LTCI costs | 1 | ||||||||

| tendency to secure own future | 0.277 *** | 1 | |||||||

| age | 0.098 * | 0.088 * | 1 | ||||||

| education | 0.172 *** | 0.228 *** | 0.120 ** | 1 | |||||

| place of residence | 0.146 *** | 0.122 *** | 0.072 * | 0.106 *** | 1 | ||||

| financing formal care | 0.311 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.290 *** | 0.121 ** | 1 | |||

| person requiring formal care | 0.230 *** | 0.131 ** | 0.140 *** | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.016 | 1 | ||

| experience with a formal caregiver | 0.390 *** | 0.244 *** | 0.067 | 0.172 *** | 0.115 ** | 0.068 * | 0.348 *** | 1 | |

| financial situation | 0.207 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.109 ** | 0.303 *** | 0.110 ** | 0.430 *** | 0.027 | 0.133 ** | 1 |

| children | 0.130 ** | 0.113 *** | 0.071 | 0.126 *** | 0.010 | 0.081 ** | 0.069 * | 0.015 | 0.137 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jurek, Ł.; Wolańska, W. Determinants of Demand for Private Long-Term Care Insurance (Empirical Evidence from Poland). Risks 2021, 9, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9010027

Jurek Ł, Wolańska W. Determinants of Demand for Private Long-Term Care Insurance (Empirical Evidence from Poland). Risks. 2021; 9(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleJurek, Łukasz, and Wioletta Wolańska. 2021. "Determinants of Demand for Private Long-Term Care Insurance (Empirical Evidence from Poland)" Risks 9, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9010027

APA StyleJurek, Ł., & Wolańska, W. (2021). Determinants of Demand for Private Long-Term Care Insurance (Empirical Evidence from Poland). Risks, 9(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9010027