Abstract

Being active in both the insurance sector and the banking sector, financial conglomerates intrinsically increase the interconnections between the banking sector and the insurance sector. We address two main concerns about financial conglomerates using a unique database on bilateral exposures between 21 French financial institutions. First, we investigate to what extent to which the insurers that are part of financial conglomerates differ from pure insurers. Second, we show that in the presence of sovereign risk, the components of a financial conglomerate are better off than if they were distinct entities. Our empirical findings bring a new perspective to the previous results of the literature based on using different types of data.

JEL classifications:

G22; G28

1. Introduction

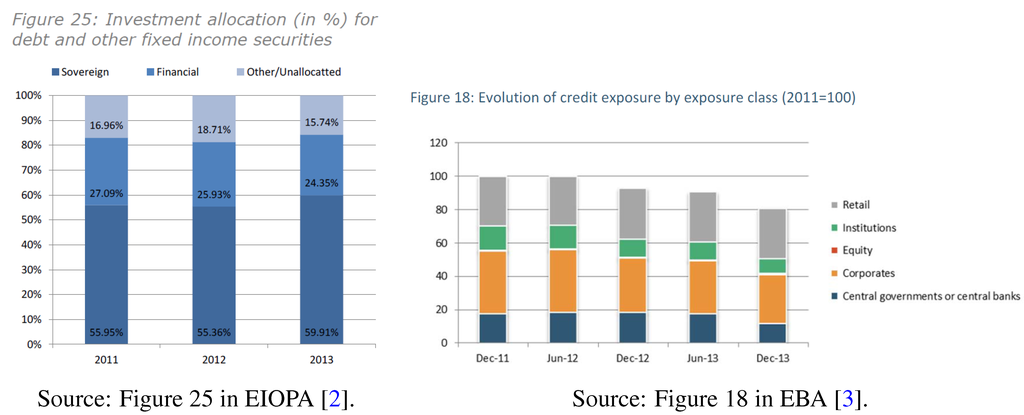

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) pinpointed interconnectedness as a key indicator of the systemic dimension of financial institutions (see FSB [1]). Figure 1 illustrates the importance of interconnections between financial institutions. It represents the aggregate asset allocation of European insurers and banks. The exposures of insurance companies to the financial sector represent about 25% of their total investments, while the exposures of banks represent about 15% of their total credit exposures. In addition, exposures to sovereign risk appear important. Sovereign exposures of banks are as large as their exposures to financial institutions. Sovereign exposures of insurance account for more than 55% of the total investments. These key facts explain the concern for the contagion risk between the banking sector and the insurance sector.

Figure 1.

Aggregate breakdown of exposure allocation of the main European insurers and banks. (a) Investment allocation (in %) for debt and other fixed income securities for the European insurance sector; (b) evolution for credit exposure by exposure class (2011 = 100) for the European banking sector.

At a global level, the general guidelines proposed by the FSB to identify systemic institutions have been derived separately for banks (see BCBS [4]) and for insurance companies (see IAIS [5]), although there exist financial conglomerates.1 In contrast, European regulation takes into account the existence of financial conglomerates (see OJEU [6]). About 70 European institutions are classified as conglomerates. On top of complying with the banking and insurance regulations, they must meet capital adequacy requirements for their whole activities. These capital adequacy requirements do not address interconnectedness, but rather risk concentration. One natural concern is therefore that financial conglomerates may be contagion pathways between the banking sector and the insurance sector. The French financial sector presents an interesting situation, since it includes several major financial conglomerates.

Our paper is an extended version of the second part of the working paper Hauton and Héam [7]. The first part of the working paper provides a comparison of several methodologies to measure the interconnectedness between financial institutions on a consolidated basis (such as the identification of core-periphery structure, for instance). The second part, which we extend here, focuses on financial conglomerates. The objective of our paper is to address two major questions: To what extent are insurers part of conglomerates different from pure insurers? To what extent are financial conglomerates modifying the vulnerability of the financial sector to contagion? Previous literature answers these questions using either market data or stand-alone accounting data. The originality of our paper is to use a new type of data: we analyze a database on the bilateral exposures of 21 French financial institutions encompassing six conglomerates, four pure banks and eleven pure insurers. The exposures of the banking and insurance components of financial conglomerates, as well as the sovereign exposures were specifically investigated for this paper.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the literature on interconnections to highlight where our contribution lies. Section 3 presents the database. It heavily relies on Hauton and Héam [7]. Section 4 uses statistical measures of exposure closeness in order to assess to what extent the insurer parts of conglomerates are different from pure insurers. Section 5 uses contagion models to analyze the risk of contagion within the financial sector. Section 6 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Firstly, we present the main theoretical arguments explaining the emergence of financial conglomerates. These motivations are similar to the explanation of linkages between banks and insurers. Before addressing in greater detail the specific motivations, the business models of banking and insurance explain a different general profile of interconnectedness. Maturity transformation leads banks to borrow partly from other financial institutions and to invest in typically non-financial firms and households. The insurance companies are expected to be exposed to the financial sector, since they invest the proceeds of the policyholders’ premium. Their liabilities are mostly composed of commitments to the policyholders; thus, the exposures of other financial institutions to insurers should be low. Being a financial conglomerate benefits from revenue enhancement and cost savings through diversification effects (see Berger and Ofek [8, van Lelyveld and Schilder [9]). For instance, a bank can use its knowledge of clients, as well as its offices to sell insurance products, too. Another motive for interconnections between banks and insurers may be risk transfers, such as reinsurance or securitization (see Subramanian and Wang [10]). This motive is less relevant for conglomerates, since risks are transferred to other subsidiaries, but remain in the same group. General opinion about the interconnection between financial institutions refers to liquidity management (see Holmstrom and Tirole [11], Rochet [12], Tirole [13]). Liquidity issues are relevant for short-term relationships, such as interbank overnight loans. Their relevance for financial conglomerates is much less clear. It is hard to narrow the advantages of being a conglomerate to a simple advantage in liquidity management. However, this strand of literature provides results worth being kept in mind when analyzing conglomerates. In particular, Allen and Gale [14] show that the degree of interconnection has an ambiguous effect on financial stability. When institutions are exposed to small and diversified shocks, the optimal structure is a complete network: the interconnections are actually generating an insurance scheme. However, when institutions are exposed to large shocks, a complete network is the worst situation. In that case, interconnections are the support of contagion: the shock is propagated to all institutions, leading to a massive cascade of defaults.

Second, most papers exploiting bilateral exposure data consider only banks. In contrast, our scope includes also financial conglomerates and insurers. Moreover, most papers analyze one national banking sector.2 In general, little evidence of solvency contagion is found. When liquidity channels are considered, contagion risk may become prominent. Liquidity channels consist of fire sales (see Cifuentes et al. [15] for instance) and liquidity hoarding (see Fourel et al. [16] for instance). These channels are relevant for banks for which core activity is maturity transformation. For insurance, liquidity concerns are less important. The unique case of international analysis is Alves et al. [17], where the interconnections between 53 major European banks are analyzed. Researchers use market data (stock prices) or accounting data (profits, turnover, etc.) to circumvent the scarcity of bilateral exposure data. Concerning contagion between insurance and banks, Schmid and Walter [18] investigate the profitability of U.S. financial firms between 1985 and 2004. One of their most relevant results for our paper is that commercial banks do not benefit from developing insurance activity. Brewer and Jackson [19] analyze the impact of three announcements in 1990 on the abnormal returns of U.S. commercial banks and U.S. life-insurers. Their empirical findings provide mixed results due to an overlapping of information effects and competitiveness effects. They show that there is less contagion risk from the insurance sector to the banking sector than from the banking sector to the insurance sector. Still on the U.S. market, Filson and Olfati [20] analyze abnormal returns following mergers of U.S. banks between 2001 and 2011. This date range includes the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act authorizing commercial banks to perform also investment banking, securities brokerage and insurance activities. They show that diversification creates value, contrasting with Schmid and Walter [18]. Analyzing extreme stock return co-movements between major financial firms of the U.S., Germany and U.K. between 1990 and 2003, Minderhoud [21] shows that correlation during normal periods is significantly different from correlation during crisis periods. Interpreting extreme co-movements as contagion phenomena, he concludes that there is contagion risk from the insurance sector to the banking sector, despite the results of Brewer and Jackson [19]. His results are two-fold: there is no diversification pattern during crisis time, but a diversification advantage may exist in standard periods. Stringa and Monks [22] study six events in the U.K. financial market between 2002 and 2003 to assess the risk of contagion from the insurance sector to the banking sector. They pinpoint the heterogeneity of banks’ responses to a distress. In particular, financial conglomerates are much more affected than pure banks. A key paper concerning European financial conglomerates is van Lelyveld and Knot [23]. The authors compare the market performances of major European financial conglomerates with the market performances of major EU banks and insurances between 1995 and 2005. They investigate if a conglomerate has a better performance than the sum of its banking part and of its insurance part. They find that the diversification effect is only a recent phenomenon. Moreover, there is a large heterogeneity of the diversification discount. The authors interpret their results as the outcome of a combination of diversification and opacity.

Empirical papers about financial conglomerates or, more generally, about spill over effects between the banking sector and the insurance sector present contrasting results. The results based on the stock returns of publicly-traded firms unveil market participants’ assessments of financial conglomerates. To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first paper to provide an empirical analysis based on a specific type of data: bilateral exposure data. Market or accounting data are a collection of individual data. Although very informative, the links that are put in evidence with such data are statistical links, such as correlation or Granger causality. In contrast, bilateral exposures are structural financial links. One aspect of our contribution is therefore to bring a new perspective to the questions previously analyzed in the literature.

3. Data

The perimeter includes all French banking groups and insurance groups with total assets larger than €10 bn, as of December 2011. We exclude publicly-oriented firm, such as development banks. This perimeter accounts for more than 85% of the French financial sector. Consequently, the dataset is composed of bilateral exposures of the 21 largest French banks and insurance groups: BNP, Crédit Agricole, Société Générale, BPCE, Crédit Mutuel and La Banque Postale are financial conglomerates; HSBC, Crédit Logement, CRHand Oseo are banks; AG2R-La Mondiale, Aviva, Axa, Allianz, CNP, Generali, Groupama, Covea, Maif, Macif and Scor are insurers. This low number of firms is explained by the high concentration of the French financial sector. For instance, the top five banking groups account for about 80% of the French banking sector. A secondary explanation is that institutions are considered on a consolidated basis aggregating potential hundreds of financial subsidiaries. This restriction comes from the used regulatory reports. In terms of size, conglomerates account for about half of the sample, while the remaining half is almost equally split between banks and insurers. We do not identify the financial institutions in the remainder of the paper due to confidentiality restrictions. Since our database is one snapshot of 2011, the representative character of this specific year is a natural concern. Since we do not have access to other snapshots of bilateral exposures, we cannot bring adamant comparisons. However, we situate year 2011 using ancillary data in Appendix A. Except for conglomerates, institutions are considered on a fully consolidated basis, gathering all classes and area of activity. For conglomerates, we distinguish a fully consolidated basis, where banking activity and insurance activity are merged, from a partially consolidated basis, where the banking component is separated from the insurance component. When conglomerates are considered on a partially consolidated basis, the sample size is 27. We collect balance sheet data from regulatory reports when available or from public financial statements otherwise. For banks and banking components of conglomerates, the exposures are derived from “large exposures” regulatory reports. These reports contains the list of all exposures larger than €300 mn or 10% of capital. In that report, an exposure to a counterpart is a double aggregation: it is the sum over all of the banking subsidiaries of all individual financial instruments associated with any subsidiaries of this specific counterpart. Each exposure is then broken down into broad financial instrument classes. We identify in the list of counterparts the financial institutions of our perimeter. In addition, we also keep major sovereign exposures. The exposures of insurers are based on security-by-security reports of French insurance entities. We identify the same counterparts as we do for banks. Since we can only access French insurance subsidiaries, there is downward bias. The impact of the bias varies across insurers according to their area of activity: the bias is almost null for domestic-oriented insurers and larger for globally-active insurers. The exposures are broken down between debt instruments and equity instruments. Debt instruments consist of debt securities, loans, deposits, etc. Equity instruments gather share securities, equity investments, etc. Note that the French financial conglomerates are banking dominant. The equity associated with the banking components represents about 90% of the total equity of the groups. Therefore, we expect the banking component to be similar to a banking group and are more interested in the behavior of the insurance component.

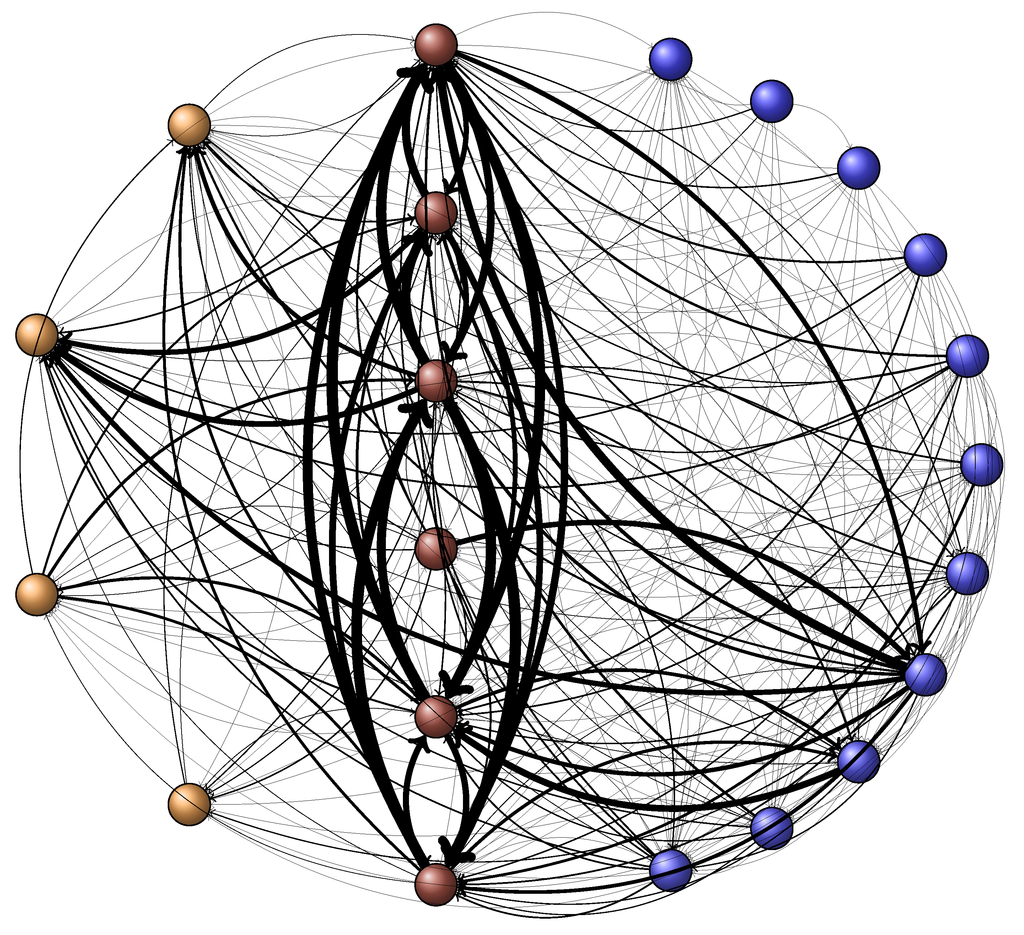

Figure 2.

Network of French financial institutions for total exposures on a consolidated basis. The node color indicates the institution class (red for conglomerates, blue for pure insurers and yellow for pure banks); the edge width is proportional to exposure. The arrow starts from the owner of the exposure and ends at the counterpart with a left bent profile. Source: ACPRdata, authors’ computation.

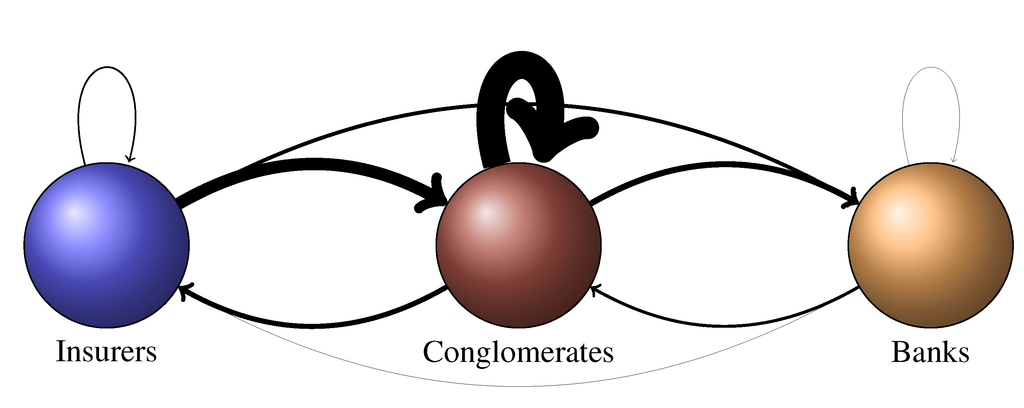

A total of €227 bn is reported. Among the 420 possible bilateral exposures, 261 are non-zero. The ratio of the two figures is called the density. With a density of 62%, the French financial network is very dense. For a comparison, the density of the banking network is about 1% in Germany (see Craig and von Peter [34]), 8% in the Netherlands (see van Lelyveld and Veld [35]), 3% in the U.K. (see Langfield et al. [36]) and varies between 10% and 20% in Italy (see Fricke and Lux [37]). This high density may be explained by the presence of insurers. Figure 2 represents the network of total exposures where institutions are considered on a full-consolidated basis. Institutions are represented by nodes. In the center, the six red nodes are the conglomerates. On the left part, the four blue nodes are the pure banks. On the right part, the eleven yellow nodes are the insurers. The arrows represent exposures between institutions. Identifying a clear pattern is a challenge. Conglomerates appears to have the largest exposures and to be connected to banks and insurers. However, we observe many exposures between insurers. Figure 3 represents the volume of exposure between sub-sectors. About 50% of the €227 bn are exposures between financial conglomerates. About 20% of the exposures are exposures of pure insurers to conglomerates. The exposures of conglomerates to the banks and to the insurers account for about 10% each. We consider that the banking component of one financial conglomerate is the parent company of the insurance component when we analyze the exposures between components of the same conglomerate. The exposure of the banking component to the insurance component is consequently composed of equity. Overall, the exposures from one component to another are approximately balanced. In a majority of cases, the insurance component is slightly more exposed to the banking component than the banking component to the insurance component. In any case, the main difference between intra-group exposures is the instrument: the bank component holds equity issued by the insurance component, whereas the insurance component holds debt instruments issued by the banking component.

Figure 3.

Volume of total exposures allocation between sectors. The node color indicates the institution class (red for conglomerates, blue for pure insurers and yellow for pure banks); the edge width is proportional to exposure. The arrow starts from the owner of the exposure and ends at the counterpart with a left bent profile. Loop arrows represent exposure within the class considered. Source: ACPR Data, authors’ computation.

This basic analysis of the exposure shows first that the network is very dense. High density is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, this feature can be seen as a diversification pattern that points towards resilience. On the other hand, Allen and Gale [14] show that a dense network is prone to widespread contagion when shocks are extreme. This dichotomy between a positive effect during normal times and a negative aspect during bad times corresponds to the empirical findings in Minderhoud [21]. Second, this analysis shows that the financial conglomerates are key players in terms of the size of institutions and exposures. At first glance, contagion can hardly occur without involving at least one of them.

4. To What Extent Are Insurers within a Conglomerate Different from Pure Insurers?

In this section, we address the similarity in terms of interconnectedness between the insurer part of a conglomerate and a stand-alone insurer. To do so, we use a distance metric between each financial institutions to see if the insurer part of a conglomerate are close to the stand-alone insurer.

4.1. Methodology

We compare the interconnectedness between financial institutions using two concepts: network integration and network substitutability (see Hauton and Héam [7]). Two institutions are said to be close in terms of network integration when they have similar exposures independent of their counterparts. Two institutions are said to be close in terms of network substitutability when they have similar exposures to the same counterparts. Network substitutability is more stringent than network integration: if two institutions are close in terms of network substitutability, they are necessarily close in terms of network integration. To illustrate the differences between these two concept, we consider a fictitious example represented by the exposure matrix given in Table 1. An exposure matrix gathers the exposures between a set of financial institutions, such that coefficient represents the exposure of institution i to institution j. Let us consider institutions A and C. Their common exposures, which are exposures to institutions B, D, E and F, are reported in Table 2. The exposure series are similar, since each amount in the exposures of institution A can be mapped to an exposure of institution C: with , with , with and with . Let us now consider institutions A and B. Their common exposures, which are exposures to institutions C, D, E and F, are reported in Table 3. The exposures are very similar, since the amounts are roughly the same and concern the same counterpart. Institution A and institution B are considered close in terms of substitutability and in terms of integration (Table 3): they lend similar volumes to the same counterparts. By contrast, institution A and institution C are close in terms of integration, but distant in terms of substitutability (Table 2): they lend similar volume,s but not to the same counterparts.

Table 1.

Fictitious example for network integration and network substitutability.

| A) | B) | C) | D) | E) | F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) | 0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| B) | 2.0 | 0 | 2.9 | 4.9 | 2.2 | 3.3 |

| C) | 1.9 | 2.9 | 0 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 2.0 |

| D) | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| E) | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0 | 1.9 |

| F) | 2.0 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 0 |

Table 2.

Fictitious example: common exposures of institutions A and C.

| A) | B) | C) | D) | E) | F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) | X | 2.7 | X | 5.0 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| C) | X | 2.9 | X | 3.1 | 5.1 | 2.0 |

Table 3.

Fictitious example: common exposures of institutions A and B.

| A) | B) | C) | D) | E) | F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) | X | X | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| B) | X | X | 2.9 | 4.9 | 2.2 | 3.3 |

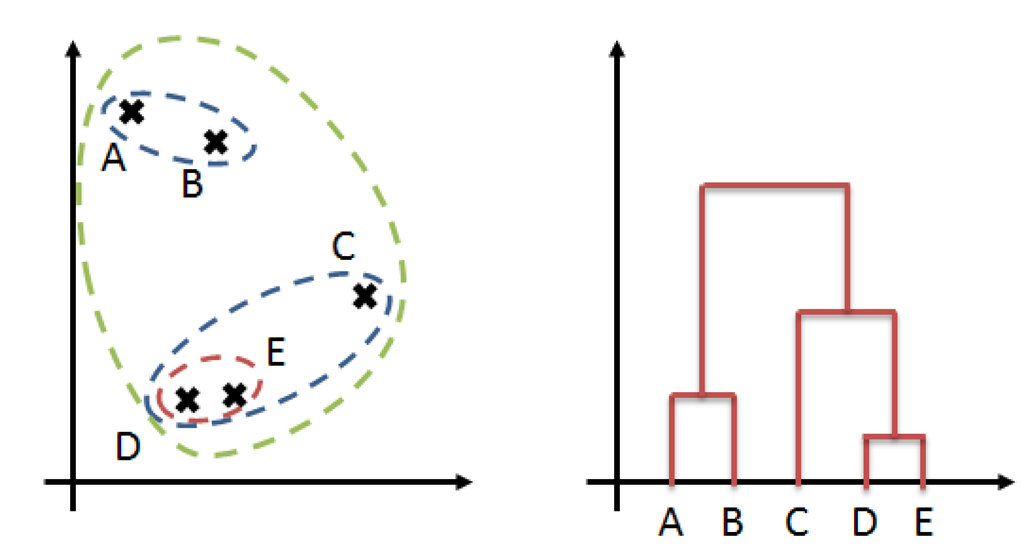

In line with these two concepts, Hauton and Héam [7] propose two metrics to quantify each dimension. These metrics are derived from a statistical background that goes beyond the scope of this paper (see Appendix B for more details). Intuitively, the metrics are based on comparing the size of exposure with or without taking into account the counterparts. The main idea is that we can build two distance matrices describing the closeness of any pair of institutions with respect to network integration and network substitutability. An interesting feature is that this process can be carried out by considering gross exposure (exposures in €), or by scaling exposures by the owner’s size (exposures in % of owner’s equity), or by scaling exposures by the issuers’ size (exposures in % of issuer’s equity). These three processes are not expected to provide the same results, as they are three distinct vantage points to look at exposures. Examining exposures in € is the basic analysis that provides insights into the stock of inter-financial assets. One drawback of this vantage point is the risk that we capture size effects rather than interconnection effects: it is natural that two institutions of similar total asset size have similar exposures. The second vantage point is adopting a credit risk perspective. Instead of considering the size of the exposure, we look at how much the exposure represents of the owner’s equity. A €10 mn loan granted from a small institution will be different from a €10 mn loan granted by a large institution. From that perspective, if two institutions appear close, they take similar risk in investing. In that approach, we have controlled for size effects. The third and last vantage point is adopting a funding risk perspective. Exposure is expressed as the percent of the equity of the issuers. Following this line, two closed institutions have similar funding strategies. Note that the two first approaches are examining the asset side, whereas with the last approach, the focus is on the liability side. Since analyzing manually a distance matrix between 27 institutions is cumbersome, we use cluster analysis. The objective is to categorize institutions, so that institutions of the same cluster are very alike. Intuitively, clusters are built step-by-step through aggregating individuals to the closest cluster. The graphical representation of a cluster analysis is a dendrogram. The axis is the threshold distance between clusters, while individuals are represented on the axis. Figure 4 presents a toy example of clustering analysis results. There are various technical ways to process the aggregation of individuals. We present the results using the Ward criterion that minimizes the inner variance (see Ward [38]). We check that our results are robust using the other following aggregating criteria: complete (that minimizes the furthest distance), group average (that minimizes the unweighted average distance) and weighted (that minimizes a weighted average distance). See Hartigan [39] for a textbook on clustering methods.

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis example. The left panel represents a population of five individuals (A to E) with the successive clusters. The right panel represents the corresponding dendrogram.

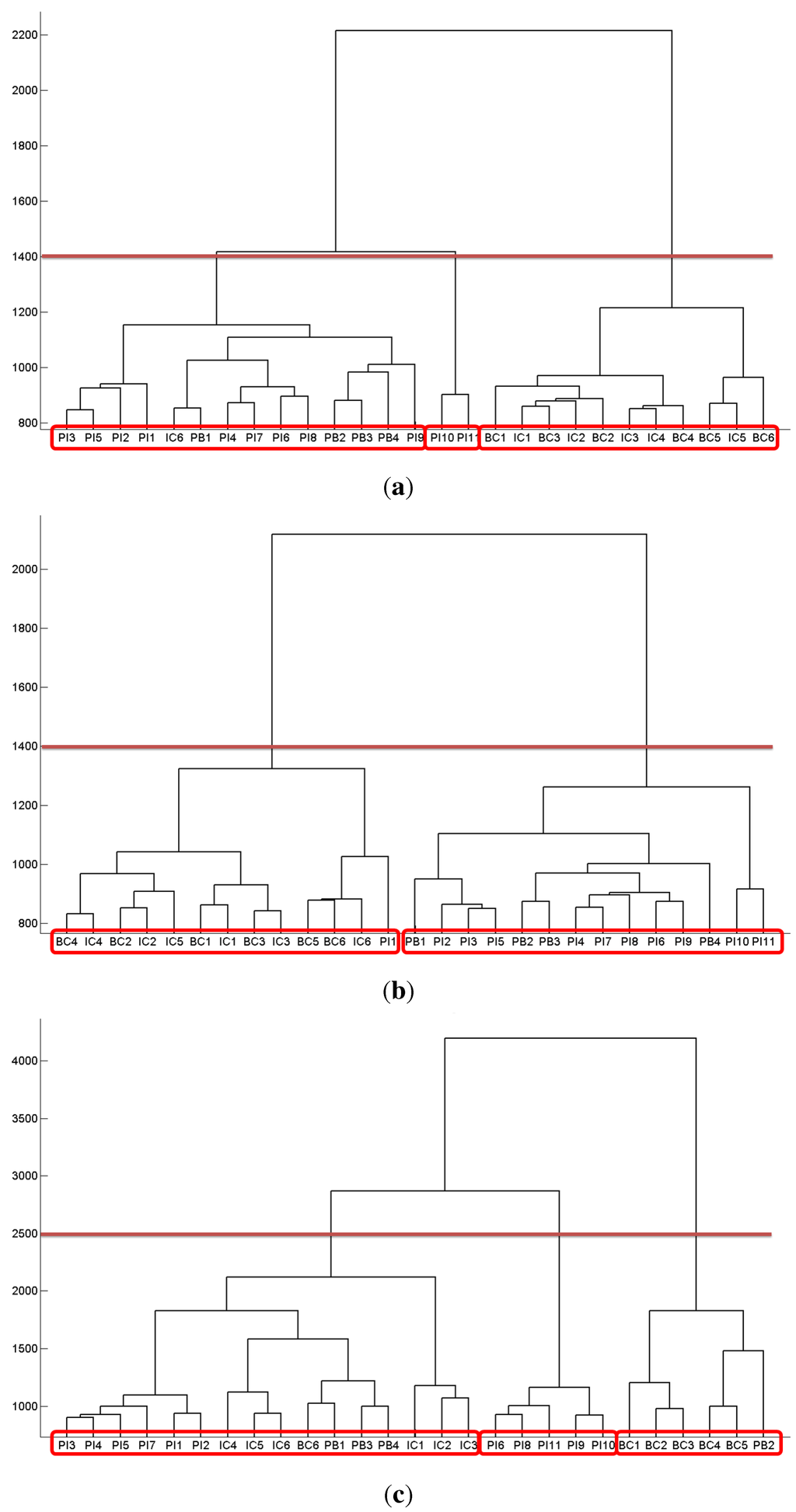

4.2. Results on Network Integration

Figure 5 presents the dendrograms for network integration when exposures are considered in € (Figure 5a), normalized by the size of the owner (Figure 5b), and normalized by the size of the issuer (Figure 5c). Each label on the x-axis represents one institution. Pure banks are labeled from PB1 to PB4; pure insurers are labeled from PI1 to PI11. The banking component of financial conglomerate i is labeled BCi, while the insurance component is labeled ICi. We use an arbitrary threshold identifying at most three clusters to ease the discussion. We distinguish three clusters for gross exposures (Figure 5a). The first cluster (on the left) is composed of all pure institutions, except for two pure insurers that form a second cluster (in the middle) and except for one insurance component. The last cluster (on the right) is composed of all components of the financial conglomerates (except the insurance component, which is in the first cluster). Therefore, the components of financial conglomerates tend to be exposed to similar volumes. These volumes are different from the volumes of pure banks and pure insurers. The volume perspective is informative, but since the size of institutions is not controlled for, we may only grasp the cluster of institutions with a similar size. Let us look at Figure 5b, where exposures are scaled by the size of the owner. Two clusters are spotted. The first one (on the left) is composed of all financial components and one pure insurer. The second cluster gathers all pure institutions (except one pure insurer). The picture is therefore similar to the analysis in terms of volumes. The components of financial conglomerates are very alike, independent of their banking or insurance activities. Finally, we adopt a funding perspective in Figure 5c. Here, almost all banking components of financial conglomerates are gathered into one cluster (on the right). Insurance components are mixed with pure banks and several pure insurers (on the left). One last cluster (in the middle) regroups five pure insurers. In a funding perspective, the components of financial conglomerates have a clearer stand: insurance components are close to insurers, while banking components form a distinct homogeneous group.

Figure 5.

Dendrograms for network integration. Legend: PIx indicates the x-th pure insurer; PBy indicates the y-th pure bank; ICz the insurance component of the z-th financial conglomerate; and BCz the banking component of the z-th financial conglomerate. Source: ACPR data, authors’ calculation. (a) Volume (exposures in €); (b) credit risk (exposures in % of owner’s equity); (c) funding risk (exposures in % of issuer’s equity).

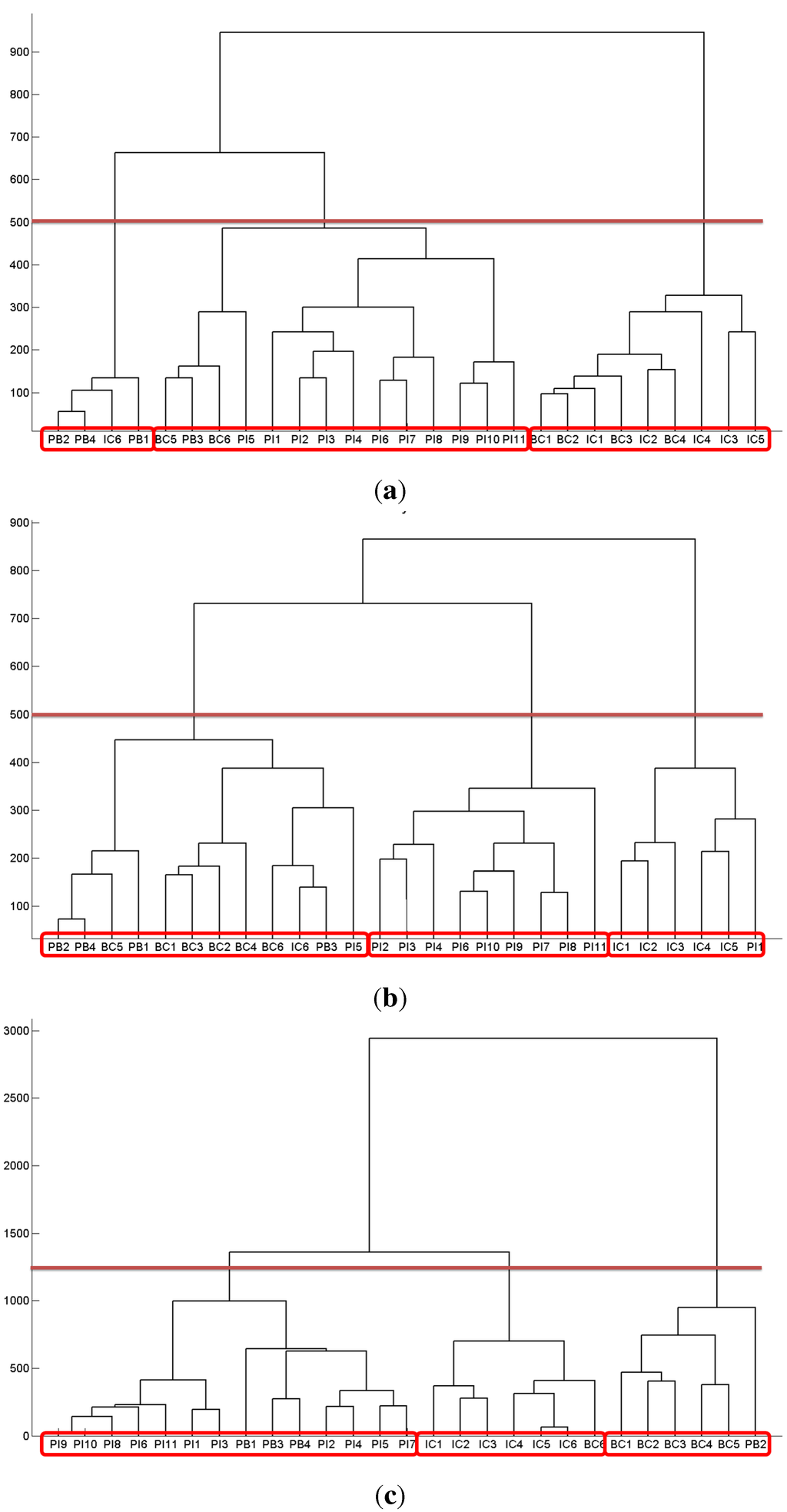

Figure 6.

Dendrograms for network substitutability. Legend: PIx indicates the x-th pure insurer; PBy indicates the y-th pure bank; ICz the insurance component of the z-th financial conglomerate; and BCz the banking component of the z-th financial conglomerate. Source: ACPR data, authors’ calculation. (a) Volume (exposures in €); (b) credit risk (exposures in % of owner’s equity); (c) funding risk (exposures in % of issuer’s equity).

4.3. Results on Network Substitutability

Figure 6 presents the dendrograms for network substitutability when exposures are considered in € (Figure 6a), normalized by the size of the owner (Figure 6b) and normalized by the size of the issuer (Figure 6c). Compared to network integration, the distance metric encompasses a comparison of the size of exposures associated with a similarity of counterparts. The substitutability in terms of volumes is analyzed in Figure 6a. Nine out of twelve components of conglomerates form a cluster (on the right). The two last clusters mix different institutions (on the left and in the middle). From that perspective, insurance components of conglomerates tend to lend similar amounts (in €) to the same counterparties as their banking homologous do. This proximity disappears when examining credit risk represented in Figure 6b. Except for a few cases, three groups can be identified: a group formed by a banking component and pure banks, a group of pure insurers and a group of insurance components. Insurance components are therefore different from their banking homologous in risk taking, but also different from pure insurers. With respect to funding risk in Figure 6c, the insurer components shape a cluster (in the middle) that is distinct from the cluster banking components (on the right) and the cluster of pure institutions (on the left). The reading is similar to the features identified for credit risk.

4.4. Conclusion on Likeliness of Insurers

The comparison of the results on network substitutability and the results on network integration leads us to draw a few stylized facts. On the asset side, the banking components and insurance components of financial conglomerates appear to have similar exposures. This proximity may come from an economy of scale in counterparty risk monitoring. However, their portfolio allocations differ. Insurance components have a clear profile distinct from their homologous and distinct from pure insurers. This feature may be explained by a diversification constraint at a group level. On the liability side, the nature of the activity is a clear discriminant. The insurance components’ funding strategy is much more like pure insurers’ strategy than that of their banking homologous. This analysis of financial assets and liabilities suggests that insurers that are part of conglomerates differ specifically and moderately from pure insurers. They tend to be more exposed than pure insurers. However, their exposures are diversified from their banking peers. On the liability side, there is a clear insurance profile where insurance components are very distinct from the banking components of conglomerates. Their funding strategy is similar to any pure insurers. Let us emphasize that the comparison is only carried out with respect to interconnectedness and brings no insight in terms of the riskiness of investments, marketing strategies, etc.

5. To What Extent Are Conglomerates Modifying Contagion Risk?

Since conglomerates are active in the banking sector and the insurance sector, a natural concern is the risk that they could facilitate the propagation of a crisis from one sector to another. Using market data, Stringa and Monks [22] or Brewer and Jackson [19] shed light on the perception of this specific concern by market participants. To bring evidence based on granular bilateral data, we use a network stress test approach. We consider specific shocks to briefly analyze the risk that the default of one institution may trigger a default cascade. We also apply common shocks based on sovereign exposures that affect simultaneously all institutions.

5.1. Methodology

A network stress test exercise is composed of a contagion model and the design of external shocks. We use the contagion model developed in Gouriéroux et al. [40]. This structural model extends the model of Eisenberg and Noe [41] by distinguishing a contagion channel based on equity instruments from a contagion channel based on debt instruments. The motivation to use the model of Gouriéroux et al. [40] is that alternative models consider only contagion based on debt instruments. Equity instruments are necessary for our analysis, since equity is a major instrument for the exposures between the components of a financial conglomerate. Using a network stress test has the advantage of comparison, since most academic papers using bilateral exposure data include a network stress test application. A network stress test is also in line with stress test exercises run by the industry, such as the 2014 stress test for European banks organized jointly by the European Banking Authority and the European Central Bank or the 2014 stress test for European insurers organized by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. Moreover, we design simple scenarios that are easy to explain. The main drawback of stress test comes from the so-called “static balance sheet assumption”. We apply a shock and look at its propagation through the system without considering any reactions of financial institutions. It is as if the shock were unexpected and sudden. We acknowledge that this assumption is a caveat for the result interpretation. However, modeling the reaction of financial institutions in a network perspective goes far beyond the scope of our paper. Let us present briefly the model of Gouriéroux et al. [40]. Consider n financial institutions interconnected through equity instruments and debt instruments. On the liability side, we denote the value of the equity of institution i and the value of the debt of institution i. On the asset side, we denote the fraction of equity instruments issued by institution j owned by institution i, the fraction of debt instruments issued by institution j owned by institution i and the value of all others assets of institutions i (loans to households, sovereign exposures, etc). For instance, means that Institution 1 owns 50% of the equity of Institution 2. The balance sheet of institution i is represented in Table 4. Denoting the nominal debt of institution i, Merton’s model written for each bank provides the following equation system:

System (1) defines a liquidation equilibrium. Gouriéroux et al. [40] show that under mild assumptions, there exists one unique liquidation equilibrium for any choice of and . The parameters , and are calibrated on the dataset, as well as the pre-shock values of external assets . Specifying the shock corresponds to computing the liquidation equilibrium with a shocked value . Let us emphasize that we consider only deterministic shocks: we analyze what happens in a given situation without quantifying the likelihood of this situation.

Table 4.

Balance sheet of institution i in Gouriéroux et al. [40].

| Asset | Liability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↔ | |||||

| ↔ | |||||

| ↔ | |||||

5.2. Stress Test with Individual Shocks

The very first concern about contagion risk and conglomerates is the risk that the default of one component is propagated to the other component, initiating a cross-sector chain of defaults. In that perspective, we consider sequentially that the external assets of each component of the six financial conglomerates are totally wiped out by assuming . For four of the financial conglomerates, the default of the banking component implies the default of the insurance component. For the last two conglomerates, the default of the banking component is not sufficient to put the insurance component into default. On the contrary, the default of the insurance component never triggers the default of the banking component. This result is in line with the fact that the banking component is much more important than the insurance component for the French conglomerates. In light of this stress test exercise, the contagion risk within a financial conglomerate is therefore clear: the insurance component is exposed to the banking component, but the reverse is false.

5.3. Stress Test with Common Shocks

Considering individual shocks is informative, but they correspond to very particular situations, which may not be representative of anticipated shocks. More realistically, we consider that contagion risk is prominent when there is a common shock that weakens all institutions. The contagion is a second-round effect that pushes the impact further. We consider shocks composed of the decrease of 50% of the sovereign exposures on major countries, since first, sovereign debt is a massive investment part of banks and insurers (especially for insurers) and, second, sovereign risk is one current major concern. We sequentially shock sovereign exposures on Germany, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and the United States of America.3 The figure of 50% corresponds to the 2011 agreement on the Greek sovereign debt (see Erlanger and Castle [42]). Sovereign exposures encompass all “official” counterparties: state debt, federal debt, municipalities bonds, hospital debt, etc. For each country, we compare the setup where financial conglomerates are split and the setup where financial conglomerate are one group. In the first setup, the two components of one conglomerate are considered as different entities, albeit exposed to one another, whereas in the second setup, they share the same fates. There is no general argument to tell which situation is the most resilient. We emphasize that the first set-up is not a perfect counter-factual representation of what may happen if conglomerates were legally split, since exposures are endogenous. If conglomerate were to be split, the exposures between the banking component and the insurer component would be somehow reallocated. This caveat should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. Although not perfect, we believe this counter-factual representation brings informative insights. Robustness checks are provided in Appendix C. Results are presented in Table 5. For Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Portugal and the United States of America, the losses do not lead any institutions to default, whatever the setup. Even the U.S. and the U.K., of which sovereign debt may be used as collateral for exchange with the corresponding financial sectors, do not lead any institution to default. For Italy, one insurance component is in default (in the split setup), whereas on a fully consolidated setup, no institution is in default. Therefore, only one insurer benefits from being part of a conglomerate. The recovery rate on the debt of this insurance component is 98%. There is a clear home bias. For France, the losses generate the default of all insurances components and one banking component in the split setup. In the consolidated setup, one financial conglomerate is in default. Consequently, five (out of six) insurers somehow benefit from being part of a conglomerate. The recovery rate on defaulted institutions is 90% for insurer components, 97% for banking components and 98% for conglomerates. With respect to these scenarios, financial conglomerates strengthen the resilience of the French financial sector, since policyholders, who are debt holders, are less likely to suffer losses.

Table 5.

Sovereign exposure stress test results. Equity recovery is the average over the non-defaulted institutions of the ratio of equity after shock and equity before shock. Debt recovery is the average over the defaulted institutions of the ratio of debt value after shock and before shock. “.” indicates that the value cannot be computed.

| Country | DE | ES | FR | UK | FR | IE | IT | PT | US |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Defaults | |||||||||

| Insurance Component | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Banking Component | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conglomerate | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Equity Recovery (%) | |||||||||

| Insurance Component | 93 | 75 | . | 100 | 94 | 93 | 61 | 83 | 99 |

| Banking Component | 91 | 96 | 71 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 86 | 97 | 86 |

| Conglomerate | 92 | 96 | 66 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 87 | 97 | 86 |

| Debt Recovery (%) | |||||||||

| Insurance Component | . | . | 90 | . | . | . | 98 | . | . |

| Banking Component | . | . | 97 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Conglomerate | . | . | 98 | . | . | . | . | . | . |

5.4. Conclusion on Contagion Risk

Using a contagion model to assess the impact of several deterministic scenarios, we find that insurance components are dependent on the banking component within the same group. Second, we find evidence towards a positive role of financial conglomerates that increases the resilience of insurers. One interpretation is that the dependence link is negative for an Armageddon scenario (such as designed for individual shock), but positive for extreme adverse shocks, such a significant sovereign crisis.

6. Conclusions

Financial conglomerates are not standard financial institutions and have been raising lively debates. We shed light on some specific aspects of these discussions. First, we compare the insurance components of financial conglomerates to pure insurers. On the liability side, we find a proximity between insurance components and pure insurers. On the asset side, insurance components appear more exposed than pure insurers, but this higher level of exposure seems offset by a diversification scheme at a group level. Second, we analyze the contagion risk. We show that for French conglomerates, which are dominated by banking activity, the insurance component is exposed to the banking component, whereas the banking component does not depend on the insurance component. However, when considering common shocks that affect both components, conglomerates appear in general more resilient than separate structures. The downside aspect of the dependence does not appear for these very adverse shocks. We exploit a unique type of database of bilateral exposures to contrast previously-established results. Moreover, most previous papers used data prior to the last financial crisis, whereas we have a snapshot of 2011. We believe it is unproductive to set the points of view against each other. Minderhoud [21] found that market participants do not value the diversification dimension of a financial conglomerate during a crisis. Our application using a stress test approach, which we believe is closer to fundamental risk, goes in the opposite direction. The explanation may lie in the argument of van Lelyveld and Knot [23], stating that the diversification bonus of financial conglomerates comes with an opacity drawback, for market participants. This opacity may appear to be more important during crisis, when market agents are said to be feverish, leading to the negative effect shown by market data. However, balance sheet data and stress test scenarios are not influenced by “animal spirits”. Another partial explanation may be that previous authors analyzed the market value of equity, while we are more concerned with debt holders (or policyholders in the case of insurers). In line with this paper, further work to understand how a financial conglomerate allocates its assets between its banking and insurance components would be interesting. Our contribution is on the risk analysis of financial conglomerates and other types of concerns, such as competitiveness, pricing or cross-sale, which would be worth taking into account.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed in the paper are only those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution.

We thank the anonymous referees for their insightful remarks and Ivan Alves, Olivier de Bandt, Monica Billio, Serges Darolles, Dominique Durant, Laure Frey, Henri Fraisse, Sarah Gandolphe, Christian Gouriéroux, Anne-Laure Kaminski, Claire Labonne and the participants of the Workshop on Stress Test organized by the Advisory Technical Committee of the European Systemic Risk Board (Frankfurt, Germany, 2014), the 7th Risk Forum (Paris, France, 2014), 14th Credit Risk Evaluation Designed for Institutional Targeting in finance Conference (Venise, Italy, 2014), the 3rd Research Workshop (London, UK, 2014), the 6th IMF Forum on Stress Test (London, UK, 2014) and the Université de Besançon Seminar for their helpful comments. This paper has also benefited from the excellent research assistance of Farida Azzi.

A. French Financial Situation in 2011

In this paper, we analyze one snapshot of the French financial sector, as of December 2011. We present here background figures on the size of interconnections and the size of sovereign exposures in order to situate the representativeness of our database.

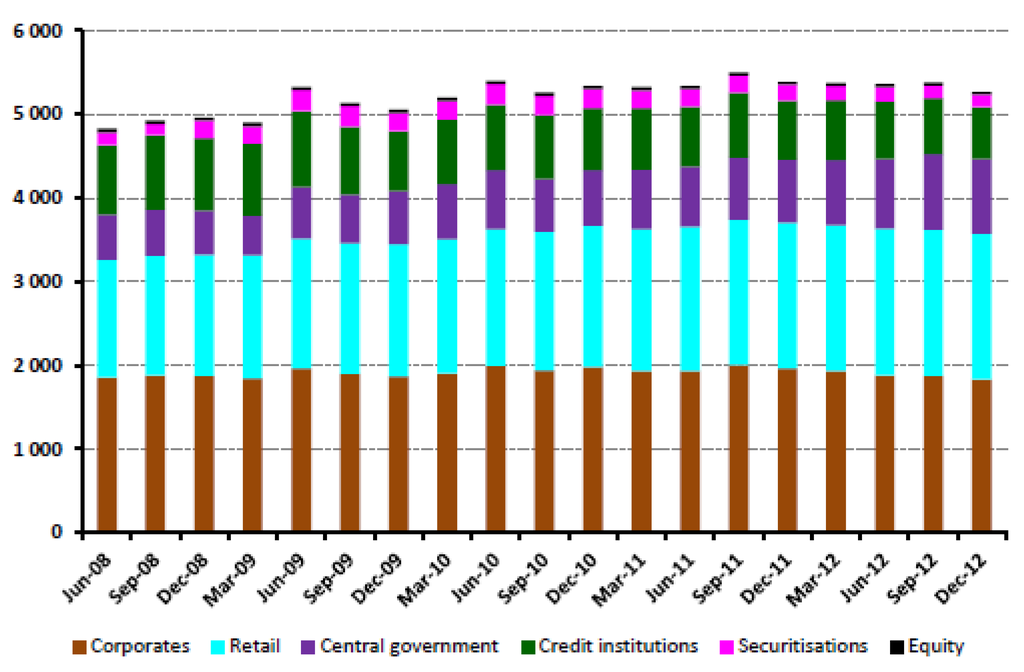

A.1. Financial Exposures

First, Alves et al. [17] developed the empirical analysis of bilateral exposure between 53 large European banks as of December 2011. About half of the exposures (in €) between these 53 large European banks have a remaining maturity higher than one year. Second, Figure A1 reports the volume of credit exposures of the French banking sector between 2008 and 2012. There is a moderate decreasing trend of the exposures to other banks (“credit institutions” category in green). This trend is confirmed over 2012 and 2013 (see Section 3.1 in ACPR [43]).

Figure A1.

Credit exposures of the French banking sector (€bn) between 2008 and 2012. Source: Chart 28 in ACP [44].

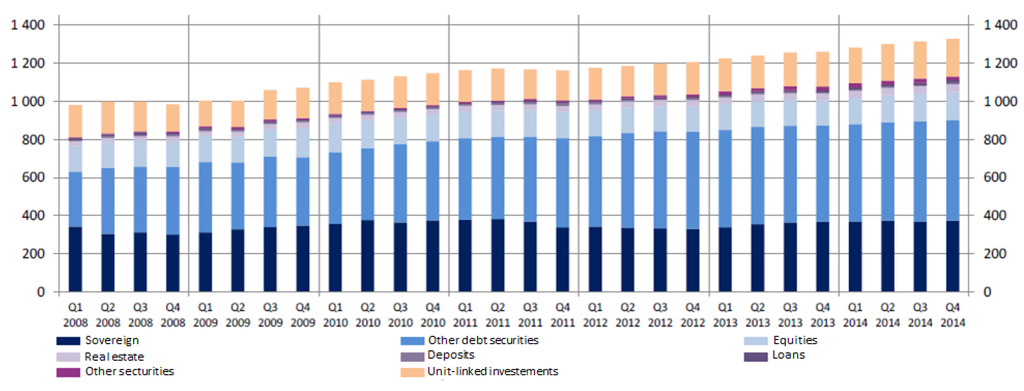

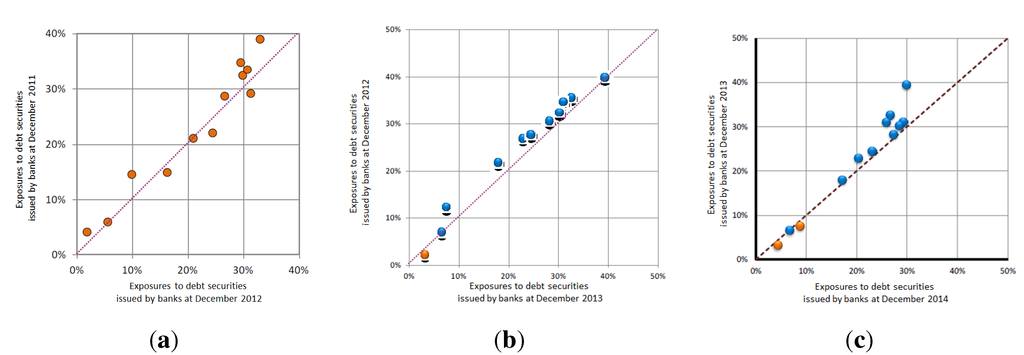

Third, Figure A2 reports the volume of investment of the 12 major French insurers between 2008 and 2014. The presented breakdown does not match our scope perfectly: the category “deposits” (in mallow) is part of the exposures to banks, but the category “other debt securities” (in intermediate blue) encompasses bonds issued by banks, insurers and industrial firms. We complement this aggregate view by reporting the annual evolution of investment in debt securities4 issued by banks in Figure A3. Since most nodes are slightly above the 45° line, we see a moderate decreasing trend in the exposures of insurers to banks.

Figure A2.

Credit exposures of the French banking sector (€bn) between 2008 and 2012. Source: Chart 6 in ACPR [45].

Figure A3.

Annual change of investment of the major French insurers through debt securities between December 2011 and December 2014. Each dot represents one insurer. When dots are colored, a blue dot indicates a decrease, while a yellow dot indicates an increase. Sources: ACP [46] for (a), ACPR [47] for (b) and ACPR [45] for (c). (a) Between 2011 and 2012; (b) between 2012 and 2013; (c) between 2013 and 2014.

These three pieces of anecdotal evidence shed light on the total intra-financial assets of French banks and insurers. The year 2011 does not appear as one exceptional year, but a regular point in the evolution of the French financial sector characterized by a slightly decreasing trend of the size of exposures. This information on the volume of exposure is not informative for the allocation of these exposures, that is the evolution of the network structure. As shown by Cocco et al. [48], there is a certain level of persistence between the banking relationship on the inter-bank market, even if loans are typically overnight loans. Considering that the network structure is constant for long-term exposures seems an acceptable first-order approximation.

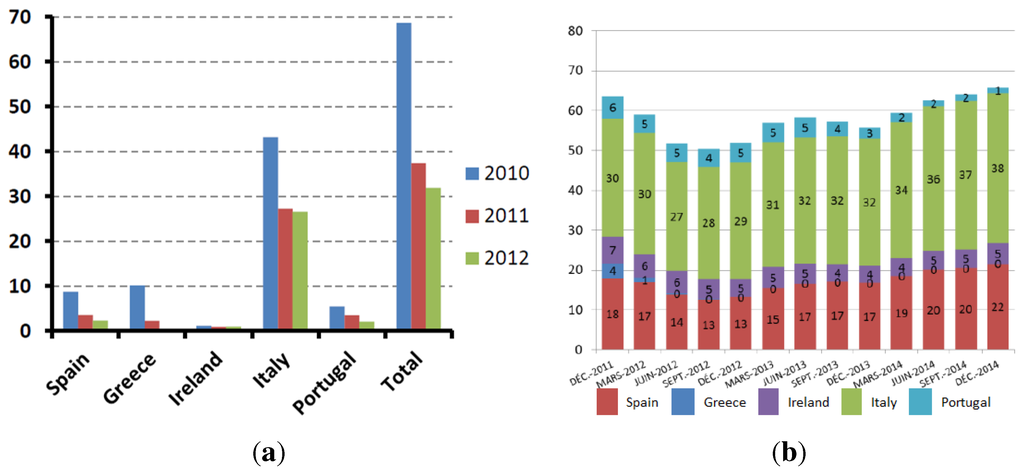

A.2. Sovereign Exposures

Figure A4 reports the evolution of exposures of European peripheral countries for major French banks and insurers, after 2011. For banks, there is a clear decrease of sovereign exposures between 2010 and 2011, followed by a stabilization period (see also Chart 31 in ACPR [43]). For insurers, there is an off-peak of exposures to Spain and Italy. Exposures to Greece, Ireland and Portugal decrease and stabilize. Moreover, exposures to sovereign debt are regularly disclosed by financial institutions. Consequently, the year 2011 is representative of current exposures to peripheral sovereign debt.

Figure A4.

Exposures to European peripheral countries for major French banks and insurers (€bn). Sources: ACP [44] for (a) and ACPR [45] for (b). (a) Exposures of major French banks to European peripheral countries; (b) exposures of major French insurers to European peripheral countries.

B. Distance Metrics

B.1. Network Integration

We call the distance between institution and institution with respect to network integration. Denoting the exposure of institution i to institution j, is defined as:

Intuitively, is the number of exposure of one institution (either or ) that are larger than the exposures of the other institutions (either or ). If the two institutions have the same exposures, then is , where n is the number of institutions. When one institution has all of its exposures larger than the other one, then is . Therefore, varies between and .

B.2. Network Substitutability

Similarly, we call the distance between institution and institution with respect to network substitutability. is defined as:

where , ordered according to . Loosely speaking, is the (weighted) sum of discrepancies of exposures of institutions and to the same counterparties.

B.3. Gross Exposures, Credit Risk Exposures and Funding Risk Exposures

Let us denote M the matrix where is the amount (in €) of institution i on institution j, and denote the equity of institution i. When we analyze gross exposures, the distance matrices and are computed with . When we analyze credit risk exposures, the distance matrices and are computed with . When we analyze funding risk exposures, the distance matrices and are computed with .

C. Robustness Check on Stress Test Exercise

In the stress test exercise for sovereign risk, we considered a haircutof 50% in line with the outcome of the Greek sovereign debt crisis. For the robustness check, we run the same exercise varying the haircut between 10% and 100%. We observe some defaults of conglomerates or some defaults of their components only in scenarios where France or Italy are shocked. For Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Portugal and the United States of America, losses never lead to default. Table A1 provides the number of defaults for different haircut levels on the Italian sovereign debt. Up to three insurance components may be in default. However, banking components and conglomerates are in no cases in default. Table A2 provides the number of defaults for different haircut levels on the French sovereign debt. The home bias is clearly present. Insurance components are more affected than banking components. For a shock up to 80%, all conglomerates are more resilient than their split-up version. For extreme shocks at haircuts of 90% and 100%, we observe two conglomerates in default, while only one banking component is in default.

Table A1.

Number of defaults for a shock on Italian sovereign debt: robustness check. When the Italian sovereign debt loses 40% of its value, one insurance component is in default, zero banking components are in default and zero conglomerates are in default.

| Haircut | Insurance Component | Banking Component | Conglomerate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 40% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 50% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 60% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 70% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 80% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 90% | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 100% | 3 | 0 | 0 |

Table A2.

Number of defaults for a shock on French sovereign debt: robustness check. When the French sovereign debt loses 40% of its value, four insurance components are in default, one banking component is in default and one conglomerate is in default.

| Haircut | Insurance Component | Banking Component | Conglomerate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 20% | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 30% | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 40% | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 50% | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 60% | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 70% | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 80% | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 90% | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| 100% | 6 | 1 | 2 |

Author Contributions

G. Hauton and J.C. Héam designed and realized the data collection ensuring that the different data bases are merged consistenly. J.C. Héam designed IT tools. G. Hauton and J.C. Héam analyzed the results. J.C Héam wrote the paper.

Author Contribution

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FSB. Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments: Initial Consideration. Basel, Switzerland: Financial Stability Board, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EIOPA. “Part I.” Financial stability report 14-105 (2014): 6–43. [Google Scholar]

- EBA. EU-wide 2014 stress-test report. London, UK: European Banking Authority, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- BCBS. Global Systemically Important Banks: Updated Assessment Methodology and the Higher Loss Absorbency Requirement. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IAIS. Global Systemically Important Insurers: Initial Assessment Methodology. London, UK: International Association of Insurance Supervisors, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OJEU. Directive on the Supplementary Supervision of Credit Institutions, Insurance Undertakings and Investment Firms in a Financial Conglomerate. Aberdeen, UK: Official Journal of the European Union, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- G. Hauton, and J.C. Héam. “How to measure interconnectedness between banks, insurers and financial conglomerates? ” In Débats Économiques et Financiers. Paris, France: Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- P.G. Berger, and E. Ofek. “Diversification’s effect on firm value.” Journal of financial economics 37 (1995): 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. van Lelyveld, and A. Schilder. “Risk in financial conglomerates: Management and supervision.” Brookings-Wharton Pap. Finan. 2003 (2003): 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Subramanian, and J. Wang. “Catastrophe risk transfer.” Check on ISSN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2321415.

- B.R. Holmstrom, and J. Tirole. “Private and public supply of liquidity.” J. Political Econom. 106 (1998): 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.C. Rochet. “Macroeconomic shocks and banking supervision.” J. Financ. Stabil. 1 (2004): 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Tirole. The theory of corporate finance. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- F. Allen, and D. Gale. “Financial contagion.” J. Political Econom. 108 (2000): 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Cifuentes, G. Ferrucci, and H.S. Shin. “Liquidity risk and contagion.” J. Euro. Econ. Assoc. 3 (2005): 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Fourel, J.C. Héam, D. Salakhova, and S. Tavolaro. Domino Effects when Banks Hoard Liquidity: The French network. Paris, France: Banque de France, 2013, Volume 432. [Google Scholar]

- I. Alves, S. Ferrari, P. Franchini, J.C. Héam, P. Jurca, S. Langfield, S. Laviola, F. Liedorp, A. Sanchez, S. Tavolaro, and G. Vuillemey. The Structure and Resilience of the European Interbank Market. Frankfurt, Germany: European Systemic Risk Board, 2013, Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- M.M. Schmid, and I. Walter. “Do financial conglomerates create or destroy economic value? ” J. Financ. Intermed. 18 (2009): 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Brewer, and W.E. Jackson. Inter-Industry Contagion and the Competitive Effects of Financial Distress Announcements: Evidence from Commercial Banks and Life Insurance Companies. Chicago, IL, USA: Federal Reserve Board of Chicago, 2002, volume 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- D. Filson, and S. Olfati. “The impacts of Gramm–Leach–Bliley bank diversification on value and risk.” J. Bank. Financ. 41 (2014): 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Minderhoud. Extreme Stock Return Co-movements of Financial Institutions: Contagion or Interdependence? Amsterdam, The Netherlands: De Nederlandsche Bank, 2003, volume 2003-16. [Google Scholar]

- M. Stringa, and A. Monks. Inter-industry contagion between UK life insurers and UK banks: an event study. London, UK: Bank of England, 2007, volume 325. [Google Scholar]

- I. van Lelyveld, and K. Knot. “Do financial conglomerates create or destroy value? Evidence for the EU.” J. Bank. Financ. 33 (2009): 2312–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.H. Furfine. “Interbank exposures: Quantifying the risk of contagion.” J. Money Credit Bank. 35 (2003): 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Wells. Financial Interlinkages in the United Kingdom’s Interbank Market and the Risk of Contagion. London, UK: Bank of England, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- C. Upper, and A. Worms. “Estimating bilateral exposures in the German interbank market: Is there a danger of contagion? ” Euro. Econ. Rev. 48 (2004): 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Á. Lublóy. “Domino effect in the Hungarian interbank market.” Hungarian Econ. Rev. 52 (2005): 377–401. [Google Scholar]

- I. van Lelyveld, and F. Liedorp. “Interbank contagion in the Dutch banking sector: A sensitivity analysis.” Int. J. Cent. Bank. 2 (2006): 99–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Degryse, and G. Nguyen. “Interbank exposures: An empirical examination of contagion risk in the Belgian banking system.” Int. J. Cent. Bank. 3 (2007): 123–171. [Google Scholar]

- M. Toivanen. Financial Interlinkages and Risk of Contagion in the Finnish Interbank Market. Helsinki, Finland: Bank of Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- P.E. Mistrulli. “Assessing financial contagion in the interbank market: Maximum entropy versus observed interbank lending patterns.” Journal of Banking 35 (2011): 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Gauthier, A. Lehar, and M. Souissi. “Macroprudential capital requirements and systemic risk.” J. Financ. Intermed. 21 (2012): 594–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Cont, A. Mousa, and E. Bastos e Santos. “Network structure and systemic risk in banking systems.” In Handbook of Systemic Risk. Edited by J. Fouque and J. Langsam. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013, chapter 11. [Google Scholar]

- B. Craig, and G. von Peter. “Interbank tiering and money center banks.” J. Financ. Intermed. 23 (2014): 322–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. van Lelyveld, and D.i. Veld. Finding the core: Network structure in interbank markets. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: De Nederlandse Bank, 2012, volume 348. [Google Scholar]

- S. Langfield, Z. Liu, and T. Ota. “Mapping the UK interbank system.” J. Bank. Financ. 45 (2014): 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Fricke, and T. Lux. “Core–periphery structure in the overnight money market: Evidence from the e-mid trading platform.” Comput. Econ. 45 (2015): 359–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.H. Ward. “Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function.” J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58 (1963): 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.A. Hartigan. Clustering Algorithms. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- C. Gouriéroux, J.C. Héam, and A. Monfort. “Bilateral exposures and systemic solvency risk.” Can. J. Econ. 45 (2012): 1273–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Eisenberg, and T.H. Noe. “Systemic risk in financial systems.” Management Sci. 47 (2001): 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Erlanger, and S. Castle. “Merkel called bankers’ bluff, getting Europe a financial plan.” New-York Times 10/27/2011 (2011): A1. [Google Scholar]

- ACPR. French banks’ performance in 2013; Analyse et Synthèse. Paris, France: Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution, 2014, volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- ACP. French Banks’ Performance in 2012,Analyse et Synthèse. Paris, France: Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel, 2013, volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- ACPR. Monitoring Inflows and Investements of 12 Major Life-Insurers as of December 2014; Analyse et Synthèse. Paris, France: Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution, 2015, volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- ACP. Monitoring Inflows and Investements of 12 Major Life-Insurers as of December 2012; Analyse et Synthèse. Paris, France: Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel, 2013, volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- ACPR. Monitoring Inflows and Investements of 12 Major Life-Insurers as of December 2013, Analyse et Synthèse. Paris, France: Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution, 2014, volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- J.F. Cocco, F.J. Gomes, and N.C. Martins. “Lending relationships in the interbank market.” J. Financ. Intermed. 18 (2009): 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1.Note that we adopt the continental European point of view: a conglomerate is a group with banking and insurance activities. This wording contrasts with an Anglo-Saxon view where “conglomerate” is often synonymous with “universal bank” (a bank mixing traditional banking activity and investment activity).

- 2.See, among others: Furfine [24] for the USA, Wells [25] for the U.K., Upper and Worms [26] for Germany, Lublóy [27] for Hungary, van Lelyveld and Liedorp [28] for the Netherlands, Degryse and Nguyen [29] for Belgium, Toivanen [30] for Finland, Mistrulli [31] for Italy, Gauthier et al. [32] for Canada, Cont et al. [33] for Brazil, Fourel et al. [16] for France, etc.

- 3.NB: for these counterparts, we get all of the exposures of insurance subsidiaries whether they are French or not, using a specific regulatory template for a financial conglomerate.

- 4.Note that during our data production process of bilateral exposures as of December 2011, almost all exposures to banks are based on debt securities.

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).