Abstract

Bank scams involving the impersonation of law enforcement personnel and financial service providers continue to proliferate across South Africa, leading to substantial economic loss and psychological harm to certain individuals in the country. The persistence of this cyber-enabled fraud indicates a significant lacuna in understanding the systemic vulnerabilities that perpetrators exploit. Specifically, there is a pressing need to examine why these scams remain successful despite existing security measures, identify the key parameters that influence individuals’ susceptibility to deception, and assess the adequacy of current preventive measures. This study navigates these notable concerns using an exploratory case study qualitative research design. Through a non-probabilistic sampling strategy, seven participants were identified to engage in discourse and contributed insights into the subject matter. A nuanced analysis identified an effective monitoring system, heightened public awareness, and stringent penalties as mitigative strategies. Subsequent studies may examine the resultant strategies broadly for wider application.

1. Introduction

This research aims to identify mitigative strategies for addressing perceived vulnerabilities contributing to law enforcement personnel impersonation of bank-related scams in South Africa. Law enforcement personnel, according to the Constitution of South Africa as adopted in 1996, are authorized agents, such as police officers and detectives, saddled with maintaining public order, enforcing statutory regulations, and ensuring the safety and security of individuals and communities. Bank scam constitutes financial fraud characterised by deliberate deception targeting the extraction of confidential information or monetary assets from individuals or financial institutions through manipulative tactics (Gayathri and Mangaiyarkarasi 2018). This practice is rooted in social engineering, impersonation, and cyber intrusion (Sarma et al. 2020). Scammers exploit psychological vulnerabilities like bounded rationality, loss aversion, trust, and urgency to manipulate and lure victims into divulging sensitive information—including banking personal credentials, users’ identification numbers, and their biometric data—or transferring funds to fraudulent accounts (Bidgoli and Grossklags 2017). These schemes frequently leverage advanced digital avenues, including social media platforms, telephone calls, and encrypted messaging applications (Pinjarkar et al. 2024), to simulate legitimacy and circumvent traditional security protocols. The sophistication of modern bank scams is further augmented with malware-infected applications, counterfeit documents, and remote access tools, significantly compromising data integrity and operational security (Aguilà Vilà 2016; Carminati et al. 2018; Mira 2024). Consequently, bank frauds substantially threaten financial stability, consumer trust, and confidence, and compromises data privacy. It is unequivocal that this critical issue requires remedial strategies grounded in scientific foundations. This imperative necessitates the current study.

Bank-related scams represent a pervasive and evolving phenomenon marked by deceptive tactics to exploit vulnerabilities within financial systems and individual user behaviours. Studies in the cybersecurity discipline indicate that financial fraud transcends geographical boundaries, affecting both developed and developing nations; thus, it remains a global manifestation. For instance, the rise of advance fee fraud, phishing attacks, and cyber fraud has been extensively documented in America, Asia, and Europe (Akinladejo 2007; Bai and Koong 2017; Bele 2020; Kemp et al. 2020; Kumari and Sharma 2023; Tambe Ebot 2023; Sirawongphatsara et al. 2024), with the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) reporting billions of dollars lost to these schemes in the USA annually (Decker 2019; Al Zaidy 2024). Similarly, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) highlights a consistent surge in cyber-enabled financial crimes across member states, with impersonation scams and fake bank websites being the most frequently reported incidents (ENISA Threat Landscape 2023). These trends illustrate the global scale and interconnectedness of bank scams, driven by the rapid proliferation of digital banking systems and social engineering techniques.

Empirical case studies from the Global South, specifically Asia and Africa, exemplify the widespread reach of bank scams. In India, for instance, the country’s national financial institution, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), has, over the years, recorded a rise in fraudulent transactions connected to SIM swapping and mobile banking-related fraud (Reserve Bank of India 2022), with reports indicating a substantial increase in victimised individuals annually. In parallel, Nigerians have observed cybercriminal groups who frequently utilise impersonation tactics through text and email to deceive bank account holders (Ama et al. 2024), resulting in significant financial losses and public mistrust in e-banking services. A comparable phenomenon has been documented in South Africa. In a recent media release, the Police Department of the South African Police Service (SAPS) has cautioned the public about scams, stressing that perpetrators pose as law enforcement personnel (South African Police Service 2025), a pattern mirrored by similar schemes and trends reported in the existing literature. The scammers in South Africa trick and intimidate people into handing over their personal and financial information, and in extreme cases, even manipulate victims into transferring funds into their fraudulent accounts:

“The offender communicates to the victim that their identifiers—such as social security numbers, passport information, or bank account details—are allegedly connected to dubious activities, including the purchase of airline tickets, the delivery of parcels, or transactions associated with human trafficking, drug smuggling, or other unlawful operations. Under the guise of determining whether the victim is a suspect or an unwitting accomplice, the fraudsters intentionally provoke a heightened sense of fear and urgency. They deceitfully declare that the individual has been marked as a potential offender and must promptly prove their innocence to prevent imminent arrest and imprisonment, thus exploiting perceived security threats. To influence the credibility of the scam, victims are often transferred to multiple officials or departments, each supposedly senior or specialised, reinforcing the illusion of a coordinated and authoritative investigation. These impersonators adopt formal, authoritative, and frequently intimidating tones to elicit compliance and fear while pretending to assist the victim through procedures intended to clear them. Subsequently, victims are instructed to participate in a video call, purportedly to provide a sworn declaration of their innocence. During this interaction, which the scammer insists must remain confidential, persistent threats and coercive strategies are employed to pressure the victim into compliance”.

The unethical and deeply entrenched forms of financial deception in South Africa, with scammers employing sophisticated tactics like masquerading as police officers, doctoring official documents, and exploiting victims through psychological intimidation, have been an issue of concern. These schemes leverage individuals’ fears of legal repercussions and harness fake communications, including malware-laden apps, to access sensitive personal and financial information. Despite ongoing warnings from law enforcement, the prevalence of such scams in the country indicates that they remain a persistent threat, continuing to exploit vulnerabilities within the country’s financial and technological infrastructure. Consequently, bank-related impersonation scams have become a lingering challenge, necessitating a comprehensive investigation of the systemic vulnerabilities and interventions.

It is worth noting that the prevalence of bank scams has significant economic repercussions, notably prompting a reversion to cash transactions as individuals and businesses seek to avoid digital fraud risks (Kovacs and David 2016; Udeh et al. 2024), thus undermining the efficiency and security of electronic financial systems in an economy. This shift increases the cost of financial intermediation by necessitating additional security measures, heightened regulatory oversight, and higher insurance premiums (Paul et al. 2023; Voganandham and Elanchezhian 2024), all of which inflate transaction costs and reduce the overall efficiency of the financial sector. In addition, the welfare implications are particularly severe for vulnerable populations (Zukry et al. 2024), especially in rural and remote areas that frequently lack the resources or knowledge to navigate complex security protocols (Iwara 2024). These shortfalls make them more susceptible to scams and financial losses. In other words, the ongoing scams, if not swiftly addressed, will exacerbate financial exclusion, erode trust in formal banking institutions, and deepen economic inequalities, ultimately impeding overall economic growth and social well-being in the country.

1.1. Aim of the Study

The primary objective of this study is to examine and identify effective mitigation strategies that can address the perceived vulnerabilities contributing to law enforcement personnel impersonation within the context of bank-related scams in South Africa.

1.2. Significance of the Study

This study is crucial for strengthening financial security, protecting the public, and enhancing trust in digital banking systems in South Africa and Africa. The findings can inform policy, guide financial institutions and customers, and enable cybersecurity experts to develop conforming mitigative and preventive strategies. In line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDGs 8,9, and 16, it fosters secure and resilient financial technologies, promotes legal accountability and fraud prevention, and safeguards individuals and businesses from financial exploitation. Addressing these impersonated bank scams through evidence-based research ensures economic stability and financial inclusion, advancing sustainable development in South Africa and across the continent.

2. Scam Mitigative Measures from a Broader Perspective

From a scholarly global perspective, researchers have delineated a comprehensive array of bank-related scam mitigation strategies, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of approaches designed to curtail fraud phenomena across diverse socio-economic contexts (see Table 1)—for instance, periodic risk and cost-benefit analysis (Aguilà Vilà 2016), public awareness and sensitisation (Bidgoli and Grossklags 2017; Bele 2020; Pinjarkar et al. 2024; Vacalares et al. 2024), stricter penalties (Bruno 2019), and stringent identification and fraud detection systems (Sarma et al. 2020; Goel 2021).

Table 1.

Strategic Interventions from the Global Perspective.

Cybersecurity strategies and threat detection in online banking systems reduce information asymmetry by providing clearer, more reliable security measures (Aguilà Vilà 2016; Pinjarkar et al. 2024). The above scholars highlight that a proactive, multilayered security approach is imperative to safeguarding online banking environments against evolving cyber risks. They emphasize the importance of implementing robust security measures such as multi-factor authentication, real-time monitoring, and user education to effectively detect, prevent, and mitigate such threats. These measures combined will ultimately improve consumer safety and trust, thereby restoring systemic integrity.

Raising awareness about scams, impersonation, and spoofing strategically bridges information gaps between perpetrators and victims (Bidgoli and Grossklags 2017; Goel 2021). To Bidgoli and Grossklags (2017), awareness should be grounded in targeted educational initiatives, such as informational campaigns, training sessions, and dissemination of best practices through media outlets and community programs. Regardless of the approach, the efforts are strategically focused on teaching individuals to recognize common scam indicators, verify caller identities through official channels, and exercise caution before disclosing personal or financial information. The empirical position of this discourse is that which systematically empowers the public to defend themselves against impersonation and bank-related fraud tendencies.

The development of protection, detection, and response strategies for impersonation fraud (Bruno 2019) and the use of community detection algorithms for bank fraud (Sarma et al. 2020) address coordination failures by fostering systematic and collaborative approaches to fraud prevention, ensuring that different stakeholders work cohesively. In addition, clarifying liability in cases like payment redirection fraud (Herbert-Lowe 2022) and strengthening regulatory frameworks (Goel 2021) aim to close enforcement gaps, ensuring accountability and effective legal resources. Similarly, examining language cues in digital communication (Vacalares et al. 2024) enhances transparency and trust, reducing information asymmetries between banks and customers. Collectively, these strategic interventions create a more resilient financial environment by systematically reducing vulnerabilities arising from informational deficiencies, enforcement shortcomings, and a lack of coordination among stakeholders.

Integrating these targeted strategies discussed above offers potential solutions to scams worldwide; however, it remains unclear how South Africa perceives their suitability for tackling the country’s specific law enforcement bank-related scams. Likewise, how effectively they are being implemented to reduce their prevalence remains uncertain. Because this form of impersonation is relatively new in academic discourse and lacks scientific attention, Goel (2021) suggests that it should be conceptualised situationally to map out context-specific interventions, as a one-size-fits-all framework may not conform to certain realities. This standpoint reflects the emphasis by Aguilà Vilà (2016) on the need for periodic risk and cost–benefit analysis by experts to determine the most suitable mitigant for implementation.

Arguably, global indicators linked to bank-related fraud may exhibit similarities when analysed, as these schemes frequently exploit universal vulnerabilities such as social engineering, digital literacy, and technological gaps. However, -localized approaches are crucial. Conceptualizing area-specific mitigative strategies tailored to South Africa’s unique technological, socio-economic, and cultural environment is imperative. This is because factors such as varying levels of digital literacy, differing regulatory systems, judicial frameworks, and socio-economic disparities influence the prevalence and nature of fraud. Similarly, the extant literature has insufficiently explored the phenomenon of law enforcement-related impersonation fraud within mainstream financial institutions, thereby leaving a significant gap in understanding criminal modalities in this context. Furthermore, a wide range of mitigation strategies advanced in literature frequently lack contextual sensitivity, as they inadequately account for the heterogeneity of rural populations, whose distinct socio-economic characteristics—such as educational attainment and access to resources—differ markedly from those residing in urban areas. This oversight highlights the necessity for a more nuanced, empirically grounded model or frameworks that address the socio-structural complexities influencing victimization and intervention efficacy across diverse geographical contexts. In other words, from South Africa’s perspective, developing targeted interventions ensures more effective prevention and enforcement mechanisms that address specific vulnerabilities within the country’s realities, rather than relying solely on generalized global mechanisms that may not fully account for local nuances.

3. Investigative Strategy

A qualitative case study research design was followed. Using purposive and snowball sampling strategies, seven (7) stakeholders in South Africa were selected (see Table 2). These are non-probability techniques where participants, intentionally determined based on specific characteristics relevant to the study’s objectives, refer and recruit additional eligible peers, aiming to gather in-depth and context-specific information from those most knowledgeable or relevant. These techniques were ideal, as the study deals specifically with law enforcement bank-related scams, a crucial, sensitive, confidential, and contextual topic. Hence, the sampling strategy aided the enrolment of strategic and key knowledge holders with a considerable level of understanding in the subject area. Two purposively selected participants, specifically a law enforcement official and a banking sector representative, facilitated the enrolment of five additional participants through referrals.

Table 2.

Participant distribution.

The data were collected through a one-on-one approach using a self-developed semi-structured interview guide. This is a qualitative data collection strategy that combines predefined questions with the flexibility to explore topics in more depth based on respondents’ answers (Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik 2021). It usually involves a set of open-ended questions structured to guide and steer the conversation during data collection; however, interviewers may adapt their probes and follow-up questions to gain deeper, richer, and more detailed insights into the inquiry. This approach was ideal, as it allows for a balance between consistency across interviews and the ability to explore unique perspectives, making it particularly useful for understanding law enforcement impersonation bank-related scams, complexities, motivations, and experiences within the context of South Africa. One critical question for all participants: Based on your professional experience, what are the perceived vulnerabilities contributing to the high incidence of law enforcement bank impersonation scams in South Africa, and how can this issue be effectively addressed?

The data collection was guided by the saturation principle, where information derived subsequently no longer contributed novel insights to existing data, thus indicating the threshold for sufficient data acquisition. At the fifth data collection point, thematic saturation was ascertained, as subsequent contributions exhibited redundancy, failing to yield substantive new insights. Nonetheless, two additional stakeholders were deliberately recruited and engaged to assess the potential for eliciting emergent perspectives, thus ensuring the robustness and comprehensiveness of the qualitative data corpus.

Consequently, collected data were transcribed, captured in Microsoft Word, coded and systematically processed through a thematic analysis model in Atlas-ti version 8. The qualitative data coding system in the thematic analysis method entails breaking down collected information into manageable segments, assigning labels, and grouping the labels into themes that reflect patterns across the data structure.

At all stages of the data collection exercise, analysis, and discussion of findings, strict confidentiality measures were observed and adhered to, ensuring participants’ sensitive information, specifically identities and privacy, were protected. As a result, identifiable details, such as the names and addresses of participants, were deliberately omitted. This provided anonymity, ensuring that individuals who voluntarily contributed valuable insights would not harbour fear of being identified.

4. Results and Discussion

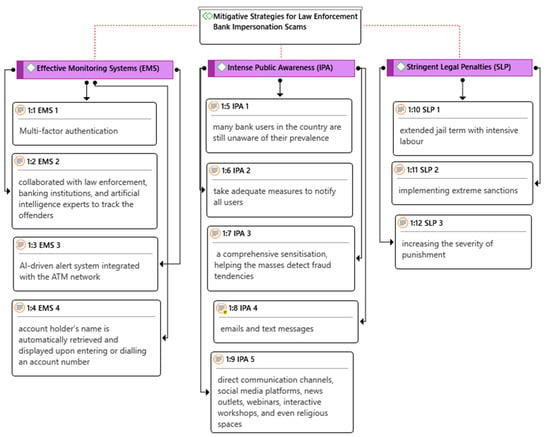

A nuanced analysis of participants’ perceptions reveals that the prevalence of law enforcement bank impersonation scams in South Africa is predominantly characterised by heightened frustration and a sense of vulnerability among individuals, financial institutions, and the government. The financial loss and psychological trauma inflicted by these scams contribute to a pervasive sense of mistrust in digital banking platforms and official communications. Similarly, the excerpts express scepticism towards the efficacy of existing security measures, bank regulatory frameworks, and the country’s judicial system concerning scams, and demand robust intervention mechanisms. Addressing this pervasive issue requires three critical strategies: an effective monitoring system, public awareness, and stringent penalties (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mitigative Strategies for Law Enforcement Bank Impersonation Scams.

An effective monitoring system entails implementing enhanced AI cybersecurity protocols within financial institutions (EMS 3) and fostering stronger collaboration between government agencies, law enforcement, and private-sector stakeholders to improve investigative and preventative responses (EMS 2). Technological innovations such as advanced authentication methods, real-time fraud detection systems, and secure communication channels (EMS 1 and 4) can significantly mitigate the risk of impersonation scams.

There is a need for widespread public awareness and sensitisation campaigns to educate citizens on recognising and avoiding impersonated bank scams (IPA 1, 2 and 3). Beyond emails and text messages, which are frequently used to reach bank users (IPA 4), social media platforms, news outlets, webinars, interactive workshops, and even religious platforms (IPA 5) are suggested as mechanisms for disseminating essential information, allowing for widespread accessibility.

The need for increased penalties for fraud (SLP 1–3), specifically law enforcement intervention in bank scams, was emphasised, highlighting that the South African judicial system tends to be lenient on such crimes. This leniency has empowered fraudsters to escalate their activities, even to the point of impersonating law enforcement, such as the SAPS. These interventions, combined, are essential to curbing the prevalence of bank impersonation scams and restoring dignity and public confidence in the financial system.

4.1. Effective Monitoring Systems

Boosting cybersecurity within the country’s financial institutions remains paramount in mitigating the escalating prevalence of bank-related impersonation scams:

“Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is a critical safeguard, fortifying bank account security, necessitating multiple verification layers to deter unauthorised access. This is particularly relevant where victims have already relayed their account details to the impersonators under duress”.(P1—Female; bank compliance officer)

The MFA system, designed to obstruct or neutralise unauthorised access to bank accounts, requires users to verify their registered identity through two or more independent personal-related credentials, like password, biometric data, or a one-time code (Goel 2021). This multi-layered verification system ensures that even if fraudsters successfully obtain bank account login credentials from victims, gaining unauthorised access to the account in their absence is impossible.

In tandem, AI-powered fraud detection systems use predictive analytics and machine learning algorithms to identify, track, and monitor anomalous transaction patterns, enabling pre-emptive intervention (Bruno 2019). Implementing such tools across financial institutions, especially a real-time monitoring system, will significantly reduce fraud tendencies:

“…there is a recent incident where this security mechanism led to the arrest of three young individuals who had lured two young women in Gauteng. The victims’ guidance, who promptly complied with the perpetrators’ request by transferring a substantial amount of Rands into the suspects’ specified accounts, collaborated with law enforcement, banking institutions, and artificial intelligence experts to track the offenders. The authorities used an AI-driven alert system integrated with the ATM network. This strategy monitors the suspects’ location when they arrive at the machine to cash out the ransom, enabling law enforcement to track and apprehend them swiftly”.(P5—Female, social worker)

The findings conform with Sarma et al. (2020), who emphasised bank fraud surveillance mechanisms through a community detection algorithm. These technological advances reinforce institutional resilience against cyber threats, significantly hindering the efficacy of impersonation scams. Collaborative engagements between financial institutions, law enforcement agencies, and cybersecurity specialists facilitate the development of sophisticated investigative methodologies, expediting the dismantling of fraudulent networks.

Participants raised concerns that the South African banking system exhibits specific vulnerabilities that heighten susceptibility to financial fraud.

“Unlike many global banking frameworks, where the account holder’s name is automatically retrieved and displayed upon entering or dialling an account number through mobile banking applications, our system necessitates that users manually save or input the recipient’s name. This manual intervention creates an exploitable vulnerability, as fraudsters can impersonate legitimate account holders by registering or proposing fictitious names that deviate from the actual account details”.(P4—Male, criminal investigator)

The narrative explains that such name retrieval vulnerability creates room for manipulation, enabling deceivers to mislead unwary individuals (victims) into transferring funds to fraudulent bank accounts. This procedural and systemic lacuna markedly exacerbates the risk of impersonation and financial scams in the country, undermining the integrity and security of the country’s banking ecosystem.

Similarly, emerging commercial financial institutions in the country that mandate minimal documentation and employ streamlined identity verification protocols have broadened access to banking services, including for undocumented migrants and opportunistic fraudsters (P2—Male, customer service manager). While this paradigm shift has facilitated financial inclusion and ostensibly enhanced the dissemination of financial services in the country, it has concurrently engendered vulnerabilities, inadvertently creating channels for illicit activities. A nuanced analysis of participants’ excerpts reveals a discernible surge in fraud incidents within these institutions, especially those operating beneath lenient regulatory oversight.

While implementing effective monitoring systems will strategically combat and mitigate bank-related impersonation scams in South Africa, there are critical trade-offs. Firstly, this approach will inevitably increase compliance costs for banks, as they need to invest in advanced technologies such as AI and MFA, staff training, and maintenance. These elevated costs could potentially be passed on to consumers in the form of higher banking fees or service charges (DeYoung and Rice 2004), which may disproportionately impact low-income users by making banking services less affordable or accessible (Iwara 2024). Consequently, while such systems enhance security and reduce fraud, they could inadvertently hinder financial inclusion by creating financial barriers for marginalised or economically vulnerable populations, potentially limiting their access to essential financial services. To approach this issue, the South African government, through its institutions and bodies such as the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA), the South African Reserve Bank’s Prudential Authority (PA), National Credit Regulator (NCR), and Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) may enforce clear caps on fees and ensure transparent disclosure of charges. In addition, these bodies can enforce effective complaint mechanisms and regularly review fee structures to ensure a fair and consumer-friendly banking environment in the country.

4.2. Intense Public Awareness

This concept entails raising moral consciousness about certain issues, frequently aiming to evoke a sense of urgency. Comprehensively sensitising the populace through targeted awareness campaigns and educational programs constitutes a fundamental strategy in curbing bank-related impersonation fraud.

A relevant question remains: why have previous awareness campaigns not been entirely effective in preventing bank scams in South Africa? Participants’ excerpts suggest a combination of behavioural biases and structural barriers. Firstly, accessibility issues, particularly in rural and remote areas, limit the reach and effectiveness of such campaigns, leaving vulnerable populations—such as the elderly and those with limited education—less informed about scam tactics. Secondly, behavioural biases such as optimism and overconfidence lead individuals to underestimate their risk or believe that scams are unlikely to affect them, reducing their motivation to adopt precautionary measures. Thirdly, learned helplessness among some groups fosters a sense of inevitability regarding scams, further diminishing engagement with preventative efforts. In other words, a more targeted, multisectoral approach is required—one that employs culturally appropriate, accessible communication channels, leverages community leaders to build trust, and incorporates behavioural insights to tailor information that effectively counteract biases, fostering greater awareness and proactive behaviour among all population segments in the country.

“…the South African law enforcement has issued a public statement, highlighting the prevalence of bank-related scams. This is a significant effort towards public awareness; however, you will agree that many bank users in the country are still unaware of their prevalence. To begin with, not every South African, especially those in rural and remote areas, has access to the press release, which limits their awareness of potential risk. Furthermore, financial institutions in the country have yet to take adequate measures to notify all users about this issue, despite the significant financial and psychological risks involved (P5-Female, social worker). In my opinion, this constitutes grave negligence on the side of the banks and a disservice to the public, who deserve to be well informed, sensitised and protected”.(P3—Female, criminal investigator)

Disseminating accurate and comprehensive information regarding prevalent impersonation bank scams is critical in enhancing societal awareness and fostering a culture of vigilance. This assumption is supported by Bidgoli and Grossklags (2017) and Iwara (2024), whose empirical findings demonstrate that informed individuals are better equipped to understand, recognise, and detect warning signs, and, as a result, critically evaluate suspicious tendencies and adopt preventive strategies. This action, in return, reduces their susceptibility to victimisation. In parallel, Bele (2020) and Vacalares et al. (2024) argue that widespread awareness campaigns on trends contribute significantly to a more resilient society; they empower individuals to make informed decisions, report suspicious activities, and collaborate in combating cybercrime. This theoretical position reflects participants’ narratives. For instance,

“We do send text messages frequently, however, I think we need to intensify the campaign”(P2-Male, Customer service)

“…notifying the public that neither the Reserve Bank, commercial financial institutions, nor South African law enforcement officers will, under no circumstances, compel individuals to transfer funds into a personal bank account, request account passwords, screenshots of users’ banking App interface, or bank statements through remote platforms can go a long way in curbing impersonated scams. Accordingly, a comprehensive sensitisation, helping the masses detect fraud tendencies and reporting such immediately to the police, is required at all levels”.(P6—Male, human rights law)

In dire situations where fraudsters constantly masquerade as government or bank officials to extort individuals, financial institutions and law enforcement agencies could efficiently explore diverse and proactive platforms to create awareness (Barker 2020), thus averting subsequent occurrences. Aside from social media platforms, news outlets, emails and text messages, which are communication channels frequently cited by scholars, participants suggest that localized webinars, interactive workshops, and even religious spaces and customary channels are effective mechanisms for disseminating essential information, ensuring widespread accessibility in urban and rural areas. Equipping South African masses with practical strategies to discern fraudulent tendencies in the country cultivates a more informed and knowledgeable public, diminishing societal susceptibility to deception and reinforcing collective cyber resilience.

4.3. Stringent Legal Penalties

In South Africa, there is a concerning public perception that criminals, even those involved in serious and life-threatening crimes, frequently enjoy privileged treatment within the criminal justice system. The assumption here is that the judicial system can effectively combat impersonation scams. Reinforcing judicial accountability by imposing stringent legal penalties, especially extended jail terms with hard labour for cybercriminals, could disincentivize fraudulent activities.

“Many incarcerated individuals in South Africa enjoy living conditions akin to luxury, with access to clean bathing facilities, proper clothing, healthy food, sound medical systems and other amenities covered with public resources, specifically taxes from patriots, working tirelessly for the country’s development. Some of these criminals even access conditions that surpass the living standards of the average South African, turning their jail terms into what resembles a vacation rather than a punishment. It is unclear what the government aim to achieve with this kind of justice system”.(P7—Female, criminal justice)

“When incarceration is seen as a comfortable and easy escape route as opposed deterrent, it completely undermines the purpose of the country’s justice system and emboldens potential offenders. The leniency and perceived impunity in the South African justice system contribute to higher crime rates, as individuals are frequently less deterred by the threat of punishment and likely to consider criminal activities as low-risk ventures with the prospect of enjoying similar privileges if apprehended. A crime of this magnitude deserves an extended jail term with intensive labour”.(P6—Male, human rights law)

A critical look at extant literature, specifically criminological studies, demonstrates a similar argument advanced by stakeholders’ views. The severity and certainty of punishment for a certain crime significantly influence criminal behaviour (Bruno 2019; Bun et al. 2020; Gacinya 2024). Although empirical evidence specifically delineating instances of police impersonation in bank fraud within the South African context and globally remains sparse, the prevailing scientific consensus suggests that a heightened penalty level enhances the perceived costs of offending. When strict legal sanctions for impersonation of bank-related scams are in place, it will reinforce judicial accountability. The implication is that offenders are held responsible for their actions, fostering public trust in the justice system. Consequently, cybercriminals will recognise that the likelihood of severe consequences outweighs the incentive to pursue fraudulent schemes, ultimately reducing cybercrime prevalence.

Participants’ concerns are legitimized in current debates around South Africa’s judicial system. A theoretical position argues that in the country, culprits frequently exhibit a diminished fear of the judicial system and incarceration resulting from systemic challenges such as perceived inefficiencies, widespread corruption, and a lack of public trust in law enforcement institutions (Olutola and Bello 2016; Bello 2021; Mphidi and Pheiffer 2025). These shortfalls, according to Du Preez and Muthaphuli (2019), undermine the deterrent effect of legal sanctions, leading perpetrators to believe that the possibility of apprehension and punishment is low. Consequently, the perceived impunity and weak enforcement strategies nurture a sense of complacency among criminals, diminishing their deterrence from engaging in illicit activities and reducing the perceived severity of jail terms.

On the contrary, while the recommendation for harsher penalties, such as extended jail terms and hard labour, for bank impersonation crimes in South Africa aims to strengthen deterrence, it raises significant concerns related to criminal justice, human rights, and legal compliance. Arguably, such punishments may conflict with international human rights standards and legal frameworks (Cameron 2020). The rights, such as those articulated by the UN principles for the protection of all persons from torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, explicitly resist harsh or punitive jail terms. This standard emphasizes the importance of proportionality, dignity, and the avoidance of cruel treatment in penal sanctions. Similarly, extreme sanctions could lead to unintended consequences, including selective enforcement that disproportionately targets certain groups (Terman and Byun 2022) and the risk of overcrowded prisons/correctional centres (Nkosi and Maweni 2020). These can undermine justice, human dignity, and social stability, as well as exert a financial burden on the South African government.

In addition to the above arguments, it remains uncertain whether increasing the severity of punishment has a more substantial deterrent effect than ensuring the certainty of punishment. This notion was articulated from the perspective that the likelihood of being caught and punished may be more influential in discouraging criminal behaviour than the harshness of penalties alone (Sherman 1993; Nagin 2013). This summation further reflects Lötter (2023). The study “Gentle Justice Reduces Recidivism and Incarceration: Can South Africa Benefit from the Finnish Experience?” highlighted two critical issues. First, South Africa’s recidivism rate remains alarmingly high, standing at 86% and 95%. This was attributed to punitive incarceration practices and limited rehabilitative support systems. In contrast, the author demonstrates that Finland’s justice system, grounded in humane treatment, reintegrative shaming, and community-based alternatives, has achieved significantly lower recidivism rates over the years. If implemented within the South African context, it will not only reduce recidivism rates but also tackle overall crime rates.

Parallel to this standpoint, Breitbach et al. (2025) argued the South African incarceration approach from a Norwegian perspective. The country’s prison system implements services with a focus on rehabilitation, vocational, educational, and therapeutic programs. These services have significantly reduced Norwegian recidivism rates by 50% between the 1990s and 2023. When compared to South Africa’s recidivism rate, which is relatively high, estimated at over 80%, there is no substantial evidence to conclude that harsher punishment and confinement conditions reduce recidivism or crime tendencies.

Although regulatory systems, judicial frameworks and socio-economic landscapes differ from one country to another, South Africa could benefit from the “gentle justice” model, which treats offenders with dignity and focuses on social reintegration rather than harsh punishment. In other words, South Africa’s policymakers must carefully consider these trade-offs to design effective, conforming, and proactive deterrence strategies.

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of law enforcement impersonation bank scams in South Africa illustrates systemic vulnerabilities, necessitating comprehensive empirical research to understand their underlying mechanisms and develop effective countermeasures. Scammers frequently exploit psychological vulnerabilities, such as trust, lack of awareness, or cognitive biases, to facilitate scam activities, resulting in significant financial losses and economic hardships. This strategic manipulation not only erodes individual trust in the mainstream banking system but also undermines overall confidence in financial institutions in the country, ultimately deterring broader participation and hindering financial inclusion. In addition, the long-term costs of maintaining such a compromised system—through regulatory oversight, increased security measures, and trust rebuilding—place a substantial strain on both banks and customers as well as the economy, significantly impeding efforts to foster a secure and inclusive financial environment in the country.

Empirical data from key stakeholders reveal three fundamental mitigative mechanisms, including an effective monitoring system, intensified public awareness, and stringent penalties. An effective monitoring system requires the implementation of AI-powered cybersecurity protocols within financial institutions. Technological innovations such as advanced authentication methods, real-time fraud detection systems, and secure communication channels can significantly mitigate the risk of impersonation scams. Similarly, collaboration between government agencies, law enforcement, financial institutions, and private-sector stakeholders can efficiently improve investigative and preventive responses. Public awareness and sensitisation campaigns to educate citizens on recognising and avoiding impersonated bank scams are imperative in this endeavour. Emails and text messages, frequently used to reach bank users, potentially demonstrate efficacy; however, platforms such as social media, news outlets, localized webinars, interactive workshops, and even religious avenues and customary channels should be effectively utilised to ensure widespread accessibility. The South African judicial system exhibits deficiencies in the adjudication and enforcement of scam offences, a systemic weakness that many stakeholders believe has contributed to the escalation of fraud incidents across the country. Although increased penalties for fraud, specifically law enforcement impersonation and bank scams, may minimize the prevalence, South African policymakers must carefully navigate these trade-offs in line with international human rights standards and legal frameworks.

6. Limitations

Due to ethical considerations and complex procedural protocols with law enforcement, identifying victims, particularly those who had filed scam-related cases, for contextual interrogation proved challenging. Future research should aim to develop methodologies that effectively navigate these complexities. As the current study employed a qualitative research design with a limited sample size of seven participants, the resulting strategies can be tested on a larger scale using statistical tools for validity, quality assurance, and application.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the University of Venda.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable publicly due to privacy or ethical restrictions; however, they are obtainable through the University management.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the research participants for their time and invaluable contributions to this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| FBI | Federal Bureau of Investigation |

| FIC | Financial Intelligence Centre |

| FSCA | Financial Sector Conduct Authority |

| IC3 | Internet Crime Complaint Center |

| NCR | National Credit Regulator |

| PA | Prudential Authority |

| RBI | Reserve Bank of India |

| SAPS | South African Police Service |

| SIM | Security Information Management |

References

- Adeoye-Olatunde, Omolola A., and Nicole L. Olenik. 2021. Research and scholarly methods: Semi-structured interviews. Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy 4: 1358–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilà Vilà, J. 2016. Identifying and Combating Cyber-Threats in the Field of Online Banking. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Computer Architecture, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/81577114.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Akinladejo, Olubusola H. 2007. Advance fee fraud: Trends and issues in the Caribbean. Journal of Financial Crime 14: 320–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zaidy, Ahmed. 2024. Counteracting Cybercrimes in Florida. Journal of Information Technology, Cybersecurity, and Artificial Intelligence 1: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ama, Godwin Agwu Ndukwe, Chibunna Onyebuchi Onwubiko, and Henry Arinze Nwankwo. 2024. Cybersecurity Challenge in Nigeria Deposit Money Banks. Journal of Information Security 15: 494–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Shuming, and Kai S. Koong. 2017. Financial and other frauds in the United States: A panel analysis approach. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 25: 413–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Rachel. 2020. The use of proactive communication through knowledge management to create awareness and educate clients on e-banking fraud prevention. South African Journal of Business Management 51: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bele, Julija Lapuh. 2020. Financial Scams, Frauds, and Threats in the Digital Age. Modern Approaches to Knowledge Management Development 39: 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, Paul Oluwatosin. 2021. Do people still repose confidence in the police? Assessing the effects of public experience of police corruption in South Africa. African Identities 19: 141–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidgoli, Morvareed, and Jens Grossklags. 2017. “Hello. This is the IRS calling”: A case study on scams, extortion, impersonation, and phone spoofing. Paper presented at 2017 APWG Symposium on Electronic Crime Research (eCrime), Phoenix, AZ, USA, April 25–27; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach, Hayes, Abby Horstmann, and Gus Beirman. 2025. Prison Environment and Conditions Affect Recidivism Rates—Norway and South Africa. INSPIRE Student Research and Engagement Conference. University of Northern Iowa. Available online: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/csbsresearchconf/2025/all/20 (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Bruno, Mario. 2019. Impersonation fraud scenarios: How to protect, detect and respond. Cyber Security: A Peer-Reviewed Journal 3: 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bun, Maurice JG, Richard Kelaher, Vasilis Sarafidis, and Don Weatherburn. 2020. Crime, deterrence and punishment revisited. Empirical Economics 59: 2303–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Edwin. 2020. The crisis of criminal justice in South Africa. South African Law Journal 137: 32–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, Michele, Mario Polino, Andrea Continella, Andrea Lanzi, F. Maggi, and Stefano Zanero. 2018. Security evaluation of a banking fraud analysis system. ACM Transactions on Privacy and Security (TOPS) 21: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, Eileen. 2019. Full Count?: Crime Rate Swings, Cybercrime Misses and Why We Don’t Really Know the Score. Journal of National Security Law & Policy 10: 583. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, Robert, and Tara Rice. 2004. How do banks make money? The fallacies of fee income. Economic Perspectives-Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago 28: 34. [Google Scholar]

- Du Preez, Nicolien, and Phumudzo Muthaphul. 2019. The deterrent value of punishment on crime prevention using judicial approaches. Just Africa 2019: 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- ENISA Threat Landscape. 2023. Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-threat-landscape-2023 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Gacinya, John. 2024. Criminal Punishment. Reviewed Journal of Social Science and Humanities 5: 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gayathri, S., and T. Mangaiyarkarasi. 2018. A critical analysis of the punjab national bank scam and its implications. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 119: 14853–66. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, Rajeev. K. 2021. Masquerading the government: Drivers of government impersonation fraud. Public Finance Review 49: 548–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert-Lowe, Simone. 2022. Payment redirection fraud–who does (and who should) bear the loss in fraudulent banking transactions, and is Australia’s electronic banking system fit for purpose? Paper presented at 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS), Hong Kong, November 10–12, vol. 1, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Iwara, Ishmael Obaeko. 2024. Optimizing PoS agent banking for inclusive rural economies: Criminal risks and strategic interventions. Journal of Academic Finance 15: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Steven, Fernando Miró-Llinares, and Asier Moneva. 2020. The dark figure and the cyber fraud rise in Europe: Evidence from Spain. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 26: 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, Levente, and Sandor David. 2016. Fraud risk in electronic payment transactions. Journal of Money Laundering Control 19: 148–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, Rachna, and Soumya Sharma. 2023. Banking Fraud: The Surging Sham of the Modern Epoch. Indian Journal of Law and Legal Research 5: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lötter, Casper. 2023. Gentle justice reduces recidivism and incarceration: Can South Africa benefit from the Finnish experience? UNISA Phronimon 13232: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, Fahad. 2024. Mobile Application Security: Malware Threat and Defenses. Paper presented at International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference, London, UK, April 3–5; pp. 461–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mphidi, Azwihangwisi Judith, and Debra Claire Pheiffer. 2025. Corruption and moral degradation within the Tshwane Metropolitan Police Department. African Security Review 34: 225–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, Daniel. S. 2013. Deterrence: A review of the evidence by a criminologist for economists. Annual Review of Economics 5: 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, Nozibusiso, and Vuyelwa Maweni. 2020. The effects of overcrowding on the rehabilitation of offenders: A case study of a correctional center, Durban (Westville), KwaZulu Natal. The Oriental Anthropologist 20: 332–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olutola, Adewale Adisa, and Paul O. Bello. 2016. An exploration of the factors associated with public trust in the South African Police Service. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies 8: 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Efijemue Oghenekome, Obunadike Callistus, Olisah Somtobe, Taiwo Esther, Kizor-Akaraiwe Somto, Odooh Clement, and Ifunanya Ejimofor. 2023. Cybersecurity strategies for safeguarding customer’s data and preventing financial fraud in the United States financial sectors. International Journal on Soft Computing 14: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinjarkar, Latika, Pawan Rajendra Hete, Mahantesh Mattada, Santosh Nejakar, Poorva Agrawal, and Gagandeep Kaur. 2024. An Examination of Prevalent Online Scams: Phishing Attacks, Banking Frauds, and E-Commerce Deceptions. Paper presented at 2024 Second International Conference on Advances in Information Technology (ICAIT), Karnataka, India, July 24–27, vol. 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reserve Bank of India. 2022. Consumer Awareness—Cyber Threats and Frauds. Available online: https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=53185 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Sarma, Dhiman, Wahidul Alam, Ishita Saha, Mohammad Nazmul Alam, Mohammad Jahangir Alam, and Sohrab Hossain. 2020. Bank fraud detection using community detection algorithm. Paper presented at 2020 Second International Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, July 15–17; pp. 642–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Lawrence William. 1993. Defiance, deterrence, and irrelevance: A theory of the criminal sanction. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 30: 445–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirawongphatsara, Patsita, Phisit Pornpongtechavanich, Pakkasit Sriamorntrakul, and Therdpong Daengsi. 2024. Exploring bank account information of nominees and scammers in Thailand. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics 13: 4439–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Police Service. 2025. SAPS Cautions Public About Scammers Using SAPS Details. Available online: https://www.saps.gov.za/newsroom/msspeechdetail.php?nid=60202 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Tambe Ebot, A. 2023. Advance fee fraud scammers’ criminal expertise and deceptive strategies: A qualitative case study. Information and Computer Security 31: 478–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terman, Rochelle, and Joshua Byun. 2022. Punishment and politicization in the international human rights regime. American Political Science Review 116: 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeh, Ezekiel Onyekachukwu, Prisca Amajuoyi, Kudirat Bukola Adeusi, and Anwulika Ogechukwu Scott. 2024. The role of big data in detecting and preventing financial fraud in digital transactions. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 22: 1746–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacalares, Sophomore T., B. P. E. S. Ana, Daryl Q. Dranto, and Jinky S. Gallano. 2024. Bank Emails: The Language of Legit and Scam. International Journal of Research and Review 11: 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voganandham, G., and G. Elanchezhian. 2024. Analysing the economic impact of credit card fraud: Activation, limit upgrades, cashback scams, discount fraud, and overdraft risks. Degrés 9: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zukry, Muhammad Amirrul Alhafiz Bin Mohd, Muhammad Nur Aqmal Bin Khatiman, and Rusli Bin Haji Abdullah. 2024. Strategies for protecting senior citizens against online banking fraud and scams: A systematic literature review. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 102: 5545–55. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).