The Implementation of ESG Indicators in the Balanced Scorecard—Case Study of LGOs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG and Strategic Performance in the Public Sector

2.2. The Balanced Scorecard in the Public Sector

2.3. Integrating ESG into the BSC Framework

2.4. Evolution and Basic Principles of e-Government

2.5. The Role of Social Media in e-Government

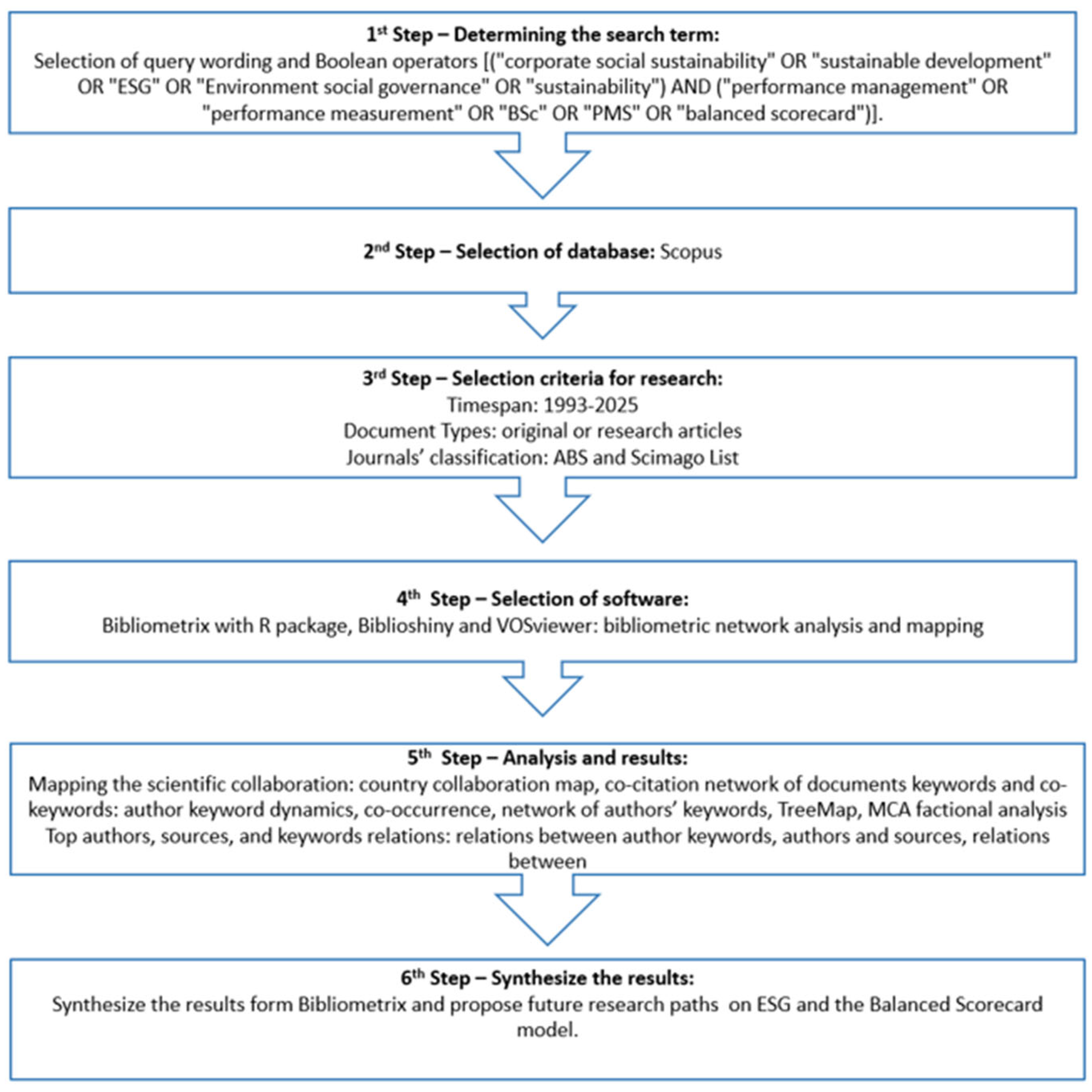

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Bibliometric Analysis

4.2. Questionnaire Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. The Proposed ESG–BSc Model for Local Government Organizations

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Questionnaire Form

- A. General Information

- □

- Man

- □

- Women

- □

- Prefer not to answer

- □

- Under 30 years old

- □

- 30–50 years old

- □

- Over 50 years old

- □

- Bachelor’s degree

- □

- Master’s degree

- □

- Phd candidate/Phd holder

- □

- Deputy Regional Governor—Thematic Deputy Regional Governor

- □

- Regional Councilor

- □

- Special Advisor

- □

- General Director

- □

- Director

- □

- Head of Department

- □

- Secretariat

- □

- Employee

- □

- Other

- B. Current use and integration of BSc & ESG

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 6)

- □

- No

- □

- Internal processes

- □

- Citizen services

- □

- Employee training

- □

- Financial sector

- □

- Other (please specify) ...........

- □

- Not at all

- □

- A little

- □

- Moderately

- □

- Very much

- □

- Very much

- □

- Not at all

- □

- A little

- □

- Moderately

- □

- Much

- □

- Very much

- □

- Yes

- □

- No (proceed to question 10)

- □

- PESTEL analysis (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal)

- □

- Porter ‘s five forces

- □

- None

- □

- Other (please specify) ...........

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 13)

- □

- No

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 15)

- □

- No

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 17)

- □

- No

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 19)

- □

- No

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 21)

- □

- No (proceed to question 22)

- □

- Improves decision-making based on ESG knowledge.

- □

- Strengthens regulatory compliance and risk management.

- □

- Enhances the Region’s organizational reputation and image.

- □

- Increases funding opportunities.

- □

- It increases employee satisfaction.

- □

- improves operational efficiency and optimizes resources.

- □

- It increases competitive advantage.

- □

- It increases long-term sustainability and resilience to external risks.

- □

- Other (please specify) ...........

- □

- Local government authorities

- □

- National and EU regulatory bodies

- □

- Private sector companies and investors

- □

- NGOs and environmental organizations

- □

- Community and civil society groups

- □

- Academic and research institutions

- □

- Employees and internal stakeholders

- □

- Citizens and service users

- □

- International ESG frameworks and organizations

- □

- Financial institutions

- □

- Other (please specify) ...........

- □

- Yes (proceed to question 27)

- □

- No (proceed to question 28)

- □

- Develop a formal ESG strategy aligned with local policies

- □

- Establish ESG performance indicators within the BSc

- □

- Provide training and capacity building for employees on ESG practices

- □

- Involving stakeholders in ESG-related decision-making processes

- □

- Enhancing transparency and accountability through ESG reporting

- □

- Implementing technological solutions for ESG data collection and analysis

- □

- Aligning ESG targets with national regulations and sustainability regulations

- □

- Collaborating with research institutions and NGOs on best practices

- □

- Lack of knowledge or expertise in implementing ESG

- □

- No benefit or added value to organizational performance

- □

- Regulatory barriers or lack of clear guidelines

- □

- Lack of internal support or leadership commitment

- □

- Financial constraints or limited budget for ESG initiatives

- □

- Limited resources (staff, tools, or technology)

- □

- Other (please specify) ...........

Appendix B. Questionnaire Analysis

| Question | Categories | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | Man | 11.8% |

| Woman | 88.2% | |

| 2. Age | Under 30 years old | 5.9% |

| 30–50 years old | 35.3% | |

| Over 50 years old | 58.8% | |

| 3. Level of Study | Holder of an undergraduate degree | 23.5% |

| Holder of a postgraduate degree | 58.8% | |

| Doctoral candidate/Holder of a doctoral degree | 17.6% | |

| 4. Role in the Organization | Deputy Regional Governor—Thematic Deputy | 5.9% (est.) |

| Regional Governor | 0 | |

| Regional Councilor | 5.9% (est.) | |

| Special Advisor | 47.1% | |

| Director | 17.6% | |

| General Director | 0 | |

| Head of Department | 29.4% | |

| Secretariat | 0 | |

| Employee | Included above |

| Question | Options | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 5. Are you involved in the strategic planning of the Region? | Yes | 35.3% |

| No | 64.7% | |

| 6. If yes, in which sector? | Internal Procedures | 14.3% |

| Citizen Service | 57.1% | |

| Training of Employees | 14.3% | |

| Financial Sector | 0% (not shown) | |

| Other | 14.3% | |

| 7. How familiar are you with the Balanced Scorecard (BSc)? (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much) | Not at all | 47.1% |

| A little | 23.5% | |

| Moderately | 23.5% | |

| Very | 5.9% (est.) | |

| Very much | 0% (not shown) | |

| 8. How familiar are you with ESG indicators? (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much) | Not at all | 58.8% |

| A little | 11.8% | |

| Moderately | 23.5% | |

| Very | 5.9% (est.) | |

| Very much | 0% (not shown) | |

| 9. Have you used the BSc for regional strategic planning? | Yes | 11.8% |

| No | 88.2% | |

| 10. If not, what another strategic tool have you used? | PESTEL Analysis | 31.3% |

| Porter’s Five Forces | 0% (not shown) | |

| None | 68.8% | |

| 11. Have you considered your strategy through the lens of ESG indicators? | Yes | 35.3% |

| No | 64.7% | |

| 12. Do you apply ESG indicators related to employee training? | Yes | 17.6% |

| No | 82.4% | |

| 13. If yes, mention the most important ones | - Training in digital governance, project management systems, geospatial data | Qualitative |

| - Training on social awareness issues, energy saving | Qualitative | |

| 14. Do you apply ESG indicators related to citizen service? | Yes | 17.6% |

| No | 82.4% | |

| 15. If yes, mention the most important ones | - Citizen service through a digital platform | Qualitative |

| - Transparency, information | ||

| - Satisfaction survey, complaint procedures | ||

| 16. Do you apply ESG indicators related to internal processes of the Region? | Yes | 17.6% |

| No | 82.4% | |

| 17. If yes, mention the most important ones | - Collectiveness, mentoring | Qualitative |

| - Electronic document management | ||

| 18. Do you apply ESG indicators related to the financial sector of the Region? | Yes | 5.9% |

| No | 94.1% | |

| 19. If yes, mention the most important ones | (No responses provided) | – |

| 20. Do you believe that the BSc is an ideal tool for monitoring the ESG indicators of the Region? | Yes | 47.1% |

| No | 52.9% |

| Question | Response Option | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 21. Reasons for using BSc to monitor ESG (multiple answers) | Improves ESG-related decision-making | 62.5% |

| Enhances compliance and risk management | 37.5% | |

| Strengthens reputation and regional image | 25% | |

| Increases funding opportunities | 12.5% | |

| Improves employee satisfaction | 75% | |

| Improves operational efficiency | 37.5% | |

| Increases competitive advantage | 37.5% | |

| Enhances long-term sustainability and resilience | 37.5% | |

| 22. Reasons for not using BSc to monitor ESG (multiple answers) | Lack of ESG information | 25% |

| Organizational resistance to change | 50% | |

| Regulatory limitations or absence of ESG guidelines | 25% | |

| Financial constraints | 25% | |

| Difficulty in defining ESG indicators | 25% | |

| Lack of expertise/training | 12.5% | |

| ESG goals don’t match organizational priorities | 12.5% | |

| Poor stakeholder collaboration | 25% | |

| We do not apply ESG indicators | 50% | |

| 23. ESG frameworks used (multiple answers) | GRI, CSRD, EFRD | Each 5.9% |

| Do not apply any | 76.5% | |

| Do not know | 17.7% | |

| 24. Who should improve ESG integration in strategic tools? (multiple answers) | Local authorities, EU bodies, private sector | Each 47.1% |

| NGOs, research institutions | Each 35.3% | |

| Civil society groups, internal employees | 29.4% | |

| International ESG bodies | 17.6% | |

| I don’t know | 11.8% | |

| 25. Do regional policies support ESG indicators? | Yes | 47.1% |

| No | 52.9% | |

| 26. Best policies to improve ESG integration (multiple answers) | Develop local ESG strategy, establish ESG indicators in BSc, train employees | Each 47.1% |

| Involve stakeholders, improve transparency | 35.3% | |

| Use ESG data technologies, align with EU standards | 29.4–35.3% | |

| Collaborate with researchers | 17.6% | |

| I don’t know | 11.8% | |

| 27. Reasons for no ESG-supporting policies (multiple answers) | Lack of ESG expertise | 66.7% |

| No added value for performance | 50% | |

| Regulatory barriers | 33.3% | |

| No internal leadership support | 25% | |

| Budget/resource limitations | 33.3% | |

| I don’t know | 8.3% |

References

- Alamillos, Rocío Redondo, and Frédéric de Mariz. 2022. How Can European Regulation on ESG Impact Business Globally? Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpenberg, Jan, and Tomasz Wnuk-Pel. 2022. Environmental performance measurement in a Swedish municipality—Motives and stages. Journal of Cleaner Production 370: 133502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, Joseph, Zaheer Khan, Geoffrey Wood, and Gary Knight. 2021. COVID-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. Journal of Business Research 136: 602–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, Amanda, and Jan Bebbington. 2008. Editorial: Accounting and reporting for sustainable development in public service organizations. Public Money and Management 28: 323–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, Ghazaleh, and Huan Liu. 2020. A survey on privacy in social media: Identification, mitigation, and applications. ACM/IMS Transactions on Data Science 1: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryer, Thomas A., and Staci M. Zavattaro. 2011. social media and public administration: Theoretical dimensions and introduction to the symposium. Administrative Theory & Praxis 33: 325–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Simon R., Peter Oosterveer, Megan Bailey, and Arthur P. J. Mol. 2015. Sustainability governance of chains and networks: A review and future outlook. Journal of Cleaner Production 107: 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, Marcos Alexandre dos Reis, and Leonardo Fenando Cruz Basso. 2025. Revisiting knowledge on ESG/CSR and financial performance: A bibliometric and systematic review of moderating variables. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge 10: 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeta, Ricardo, and Sergio Palomero. 2011. Methodological proposal for business sustainability management by means of the Balanced Scorecard. Journal of the Operational Research Society 62: 1344–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Yee-Ching Lilian. 2004. Performance measurement and adoption of balanced scorecards: A survey of municipal governments in the USA and Canada. International Journal of Public Sector Management 17: 204–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ying, and Laihui Xie. 2015. China’s Social Science Research on Climate Change and Global Environmental Change. In World Scientific Reference on Asia and the World Economy. Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 183–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhongfei, and Guanxia Xie. 2022. ESG disclosure and financial performance: Moderating role of ESG investors. International Review of Financial Analysis 83: 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortesi, Anna, Ioannis Vardopoulos, and Luca Salvati. 2022. A Partial Least Squares Analysis of the Perceived Impact of Sustainable Real Estate Design upon Wellbeing. Urban Science 6: 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, Matteo, Pier Luigi Giardino, Riccardo Camilli, and Ivo Hristov. 2023. Unlocking the sustainability of medium enterprises: A framework for reducing cognitive biases in sustainable performance management. Journal of Management and Organization 30: 490–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, Caterina, Pasquale Pazienza, and Mark Bartlett. 2020. Does good ESG lead to better financial performances by firms? Machine learning and logistic regression models of public enterprises in Europe. Sustainability 12: 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Sordo, Carlotta, Rebecca L. Orelli, Emanuele Padovani, and Silvia Gardini. 2012. Assessing Global Performance in Universities: An Application of Balanced Scorecard. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 46: 4793–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Marc J., and Priscilla S. Wisner. 2001. Using a Balanced Scorecard to Implement Sustainability. Environmental Quality Management 11: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskantar, Marianna, Constantin Zopounidis, Michalis Doumpos, Emilios Galariotis, and Khaled Guesmi. 2024. Navigating ESG complexity: An in-depth analysis of sustainability criteria, frameworks, and impact assessment. International Review of Financial Analysis 95: 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farneti, Federica. 2009. Balanced scorecard implementation in an Italian local government organization. Public Money and Management 29: 313–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, Mary K., and Gregory Porumbescu. 2021. The limits of social media for public administration research and practice. Public Administration Review 81: 787–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, Frank, Tobias Hahn, Stefan Schaltegger, and Marcus Wagner. 2002. The sustainability balanced scorecard—Linking sustainability management to business strategy. Business Strategy and the Environment 11: 269–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Chengbo, Lei Lu, and Mansoor Pirabi. 2023. Advancing green finance: A review of sustainable development. Digital Economy and Sustainable Development 1: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, Stuart L., Andrew Koch, and Laura T. Starks. 2021. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance 66: 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggiola, G. 2010. IFRS Adoption In The E.U., Accounting Harmonization And Markets Efficiency: A Review 1. Available online: www.iasplus.com (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Hansen, Erik G., and Stefan Schaltegger. 2016. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures. Journal of Business Ethics 133: 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Erik G., and Stefan Schaltegger. 2018. Sustainability Balanced Scorecards and their Architectures: Irrelevant or Misunderstood? Journal of Business Ethics 150: 937–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Zahirul. 2014. 20 years of studies on the balanced scorecard: Trends, accomplishments, gaps and opportunities for future research. The British Accounting Review 46: 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, Ivo, Andrea Appolloni, Antonio Chirico, and Wenjuan Cheng. 2021. The role of the environmental dimension in the performance management system: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production 293: 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, Ivo, Antonio Chirico, and Andrea Appolloni. 2019. Sustainability value creation, survival, and growth of the company: A critical perspective in the sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC). Sustainability 11: 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Yu-Lung, and Chun-Chu Liu. 2010. Environmental performance evaluation and strategy management using balanced scorecard. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 170: 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, Luminita. 2016. Ionescu, Luminita. 2016. e-Government and social media as effective tools in controlling corruption in public administration. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets 11: 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, Vishakha, and Keyur Thaker. 2024. Studying research in balanced scorecard over the years in performance management systems: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 73: 2558–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 1992. The Balanced Scorecard-Measures That Drive Performance. Available online: https://hbr.org/1992/01/the-balanced-scorecard-measures-that-drive-performance-2 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 1996. Strategic learning & the balanced scorecard. Strategy & Leadership 24: 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Satish, Weng Marc Lim, Riya Sureka, Charbel Jose Chiappetta Jabbour, and Umesh Bamel. 2024. Balanced Scorecard: Trends, Developments, and Future Directions. Berlin: Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Guozhu, Zixuan Sun, Qingqin Wang, Shuai Wang, Kailiang Huang, Naini Zhao, Yanqiang Di, Xudong Zhao, and Zishang Zhu. 2023. China’s green data center development: Policies and carbon reduction technology path. Environmental Research 231: 116248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Rongrong, Feng Ren, and Qiang Wang. 2024. China–US scientific collaboration on sustainable development amidst geopolitical tensions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, Iain, and Irene-Marié Esser. 2022. From a Financial to an Entity Model of ESG. European Business Organization Law Review 23: 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, Bernard, and James Creelman. 2011. Conclusion and Key Strategic Performance Questions. In More with Less. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, Chiara, Antonio Costantini, and Silvia Panfilo. 2022. Performance measurement tools for sustainable business: A systematic literature review on the sustainability balanced scorecard use. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29: 367–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, Sónia, and Verónica Ribeiro. 2017. The Balanced Scorecard as a Tool for Environmental Management: Approaching the Business Context to the Public Sector. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, Dana M. 2022. Sustainable Investing and Fiduciary Obligations in Pension Funds: The Need for Sustainable Regulation. American Business Law Journal 59: 621–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørreklit, Hanne. 2003. The Balanced Scorecard: What is the score? A rhetorical analysis of the Balanced Scorecard. Accounting, Organizations and Society 28: 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, Ioannis. 2024a. The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0. Encyclopedia 4: 1711–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, Ioannis. 2024b. Bibliometric Analysis: The Main Steps. Encyclopedia 4: 1014–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricevic, Olga, and David J. Teece. 2019. The structural reshaping of globalization: Implications for strategic sectors, profiting from innovation, and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies 50: 1487–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineyrua, Diego G. Ferber, Alfonso Redondo, José A. Pascual, and Ángel M. Gento. 2021. Knowledge management and sustainable balanced scorecard: Practical application to a service sme. Sustainability 13: 7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, Meri, Lotta-Maria Sinervo, and Kaisa Kurkela. 2024. Premises for sustainability—Participatory budgeting as a way to construct collaborative innovation capacity in local government. Accounting and Financial Management Journal of Public Budgeting 36: 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, Konstantina, Ioannis Passas, Alexandros Garefalakis, and Constantin Zopounidis. 2023. ESG in Construction Risk Management. Hershey: IGI Global, ch. 3. pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjito, Aris. 2023. Sarjito, Aris. 2023. The Influence of social media on Public Administration. Journal Terapan Pemerintahan Minangkabau 3: 106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, Delphine Gibassier, and Dimitar Zvezdov. 2013. Is environmental management accounting a discipline? A bibliometric literature review. Meditari Accountancy Research 21: 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serino, Marco, Ilenia Picardi, and Giancarlo Ragozini. 2024. Mapping epistemic pluralism: A network analysis of discursive practices in communities promoting refused knowledge about healthcare and wellbeing. Poetics 107: 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, Fabricio, Michelle P. de Arruda, Keysa M. C. de Mascena, and João M. G. Boaventura. 2020. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: A classification model. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 2071–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamis, George, Georgios Evangelos, Aris Papakostas, Giannis Vassiliou, Michael Grafanakis, Alexandros Garefalakis, Michalis Vassalos, Anastasia Mylona, and Nikos Papadakis. 2025. Cost-Effective Design, Content Management System Implementation and Artificial Intelligence Support of Greek Government AADE, myDATA Web Service for Generic Government Infrastructure, a Complete Analysis. Algorithms 18: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States. 1992. United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/agenda21.htm (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Visser, Wayne. 2013. Corporate Sustainability & Responsibility: An Introductory Text on CSR Theory & Practice—Past, Present & Future. Cambridge: Kaleidoscope Futures Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Jieru, Libo Yin, and You Wu. 2024. Return and volatility connectedness across global ESG stock indexes: Evidence from the time-frequency domain analysis. International Review of Economics and Finance 89: 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Belinda. 2015. The local Government accountants’ perspective on sustainability. Management and Policy Journal Sustainability Accounting 6: 267–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopounidis, Constantin, Alexandros Garefalakis, Christos Lemonakis, and Ioannis Passas. 2020. Environmental, social and corporate governance framework for corporate disclosure: A multicriteria dimension analysis approach. Management Decision 58: 2473–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garefalakis, S.; Angelaki, E.; Spinthiropoulos, K.; Tsamis, G.; Garefalakis, A. The Implementation of ESG Indicators in the Balanced Scorecard—Case Study of LGOs. Risks 2025, 13, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13080154

Garefalakis S, Angelaki E, Spinthiropoulos K, Tsamis G, Garefalakis A. The Implementation of ESG Indicators in the Balanced Scorecard—Case Study of LGOs. Risks. 2025; 13(8):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13080154

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarefalakis, Stavros, Erasmia Angelaki, Kostantinos Spinthiropoulos, George Tsamis, and Alexandros Garefalakis. 2025. "The Implementation of ESG Indicators in the Balanced Scorecard—Case Study of LGOs" Risks 13, no. 8: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13080154

APA StyleGarefalakis, S., Angelaki, E., Spinthiropoulos, K., Tsamis, G., & Garefalakis, A. (2025). The Implementation of ESG Indicators in the Balanced Scorecard—Case Study of LGOs. Risks, 13(8), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks13080154